Published online Jun 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i6.107235

Revised: April 12, 2025

Accepted: May 9, 2025

Published online: June 27, 2025

Processing time: 73 Days and 1.6 Hours

Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIPO) is a rare and debilitating disorder, characterized by severe impairments in gastrointestinal motility. The affected sites include the enteric/intrinsic autonomic nerves (neuropathy), intestinal smooth muscle cells (myopathy), and interstitial cells of Cajal (mesenchymopathy). The etiology can be genetic, idiopathic, or acquired. Owing to its nonspecific clinical presentation and lack of definitive diagnostic methods, misdiagnosis of CIPO is common.

This case involved an older male with insidious onset in adolescence who presented with postprandial bloating, intermittent diarrhea, and weight loss. During the disease course, the patient experienced two episodes of intestinal obstruction. Imaging revealed multisegmental digestive tract abnormalities (gastric emptying disorder, significant duodenal dilatation, and segmental jejunal dilatation). Whole-exome sequencing revealed a rare MYH11 mutation [NM_0010

This report adds to our current understanding of CIPO etiology by reinforcing the role of MYH11 variants in the pathogenesis of the CIPO phenotype.

Core Tip: Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIPO) is a rare disorder, characterized by severe impairments of gas

- Citation: Jiang S, Zhou YX, Sun XH, Chen PP, Tang H, Chen Y, Liu YP, Li YX, Kang L. Hereditary chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction caused by a rare MYH11 mutation: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(6): 107235

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i6/107235.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i6.107235

Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIPO) is characterized by severely impaired gastrointestinal motility. Owing to their nonspecific clinical manifestations and a lack of definitive diagnostic methods, patients are often diagnosed at an advanced stage, with many undergoing unnecessary surgical procedures and experiencing high rates of misdiagnosis, delayed diagnosis, and inappropriate treatment. CIPO management is challenging, requiring a multidisciplinary approach involving experienced specialists in radiology, gastrointestinal motility, nutrition, and surgery. This case involved an older male with insidious onset in adolescence; however, the diagnosis was made decades later. Genetic analysis through whole-exome sequencing (WES) revealed a rare MYH11 gene. To our knowledge, this is the sixth reported case of CIPO with a heterozygous MYH11 mutation [NM_001040113.2: C.5819del (p.Pro1940HisfsTer91)].

A 77-year-old male patient presented to the Department of Geriatric Medicine, Peking Union Medical College Hospital in November 2024.

Over the past year, the patient had experienced increased frequency and severity of postprandial abdominal distension, intermittently accompanied by nausea and vomiting. The abdominal distension was relieved after vomiting. However, the effectiveness of prokinetic medications had become less pronounced. The episodes of diarrhea also became more frequent, occurring several times per month and presenting as watery stools without fever, mucus, or blood. The symptoms improved with antibiotics and anti-diarrheal medications. The bowel movements were normal in the absence of diarrhea. During this period, the patient’s weight decreased from 50 kg to 40 kg, with reported significant fatigue and decreased mobility. The patient became increasingly bedridden but remained capable of self-care. Two months previously, the patient had required a urinary catheter because of recurrent urinary retention.

The patient had a history of intermittent abdominal bloating and diarrhea for > 60 years, which had worsened in the past year and was accompanied by significant weight loss. The patient reported having experienced postprandial bloating since adolescence, which was attributed to “indigestion”. The patient often experienced episodes of diarrhea triggered by the consumption of unhygienic food, which was relieved by anti-diarrheal medication. In 2001, the patient developed severe abdominal distension with reduced bowel movements, and abdominal computed tomography (CT) imaging findings suggested partial intestinal obstruction, which improved with conservative management. In 2008, the patient had another episode of severe abdominal distension with a 1-week cessation of bowel movements, leading to a diagnosis of “intestinal obstruction”. The patient underwent ileocecal resection with ileocolic anastomosis at a local hospital. The patient’s medical history was negative for diabetes and toxin exposure; however, the patient reported a history of heavy alcohol consumption for > 40 years.

The patient’s father had a history of intestinal obstruction, and one of the patient’s six siblings had died of intestinal obstruction, although the others had no related symptoms.

On admission, the patient appeared emaciated, with a body mass index of 14 kg/m². The cardiopulmonary examination results were unremarkable. The patient exhibited generalized muscle atrophy, grade IV proximal limb muscle strength, and decreased pinprick sensation below the knees.

Laboratory tests revealed mild anemia [hemoglobin (HGB), 106 g/L] and normal urinalysis, cardiac enzyme levels, and liver and kidney functions. The patient’s serum albumin level was 33 g/L, the prealbumin level was 140 mg/L, and inflammatory marker levels were within normal limits. The folate and vitamin B12 levels were normal with regular vitamin B12 supplementation over the past 6 months. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed multiple dilated small bowel loops with an aortomesenteric angle of approximately 36°.

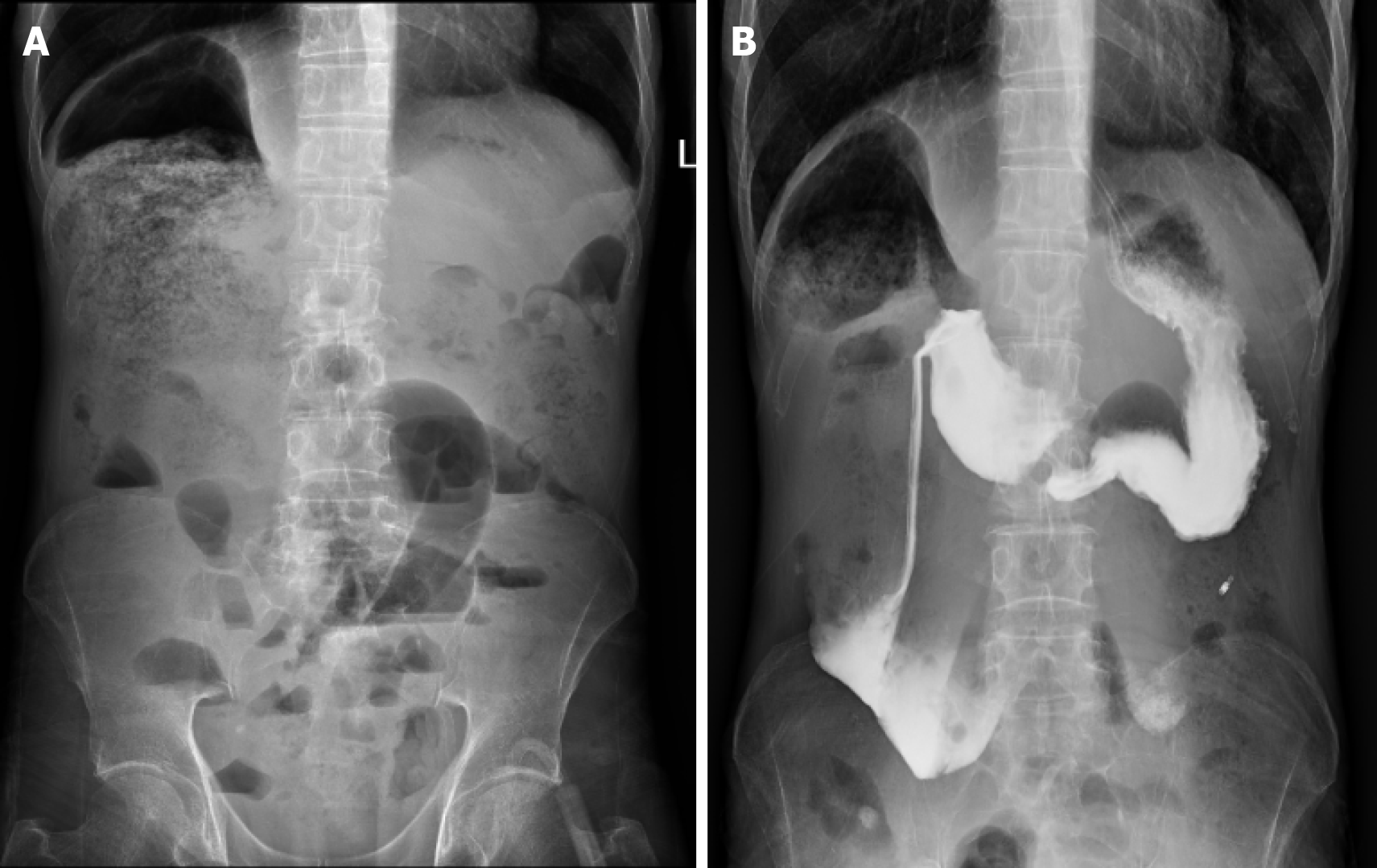

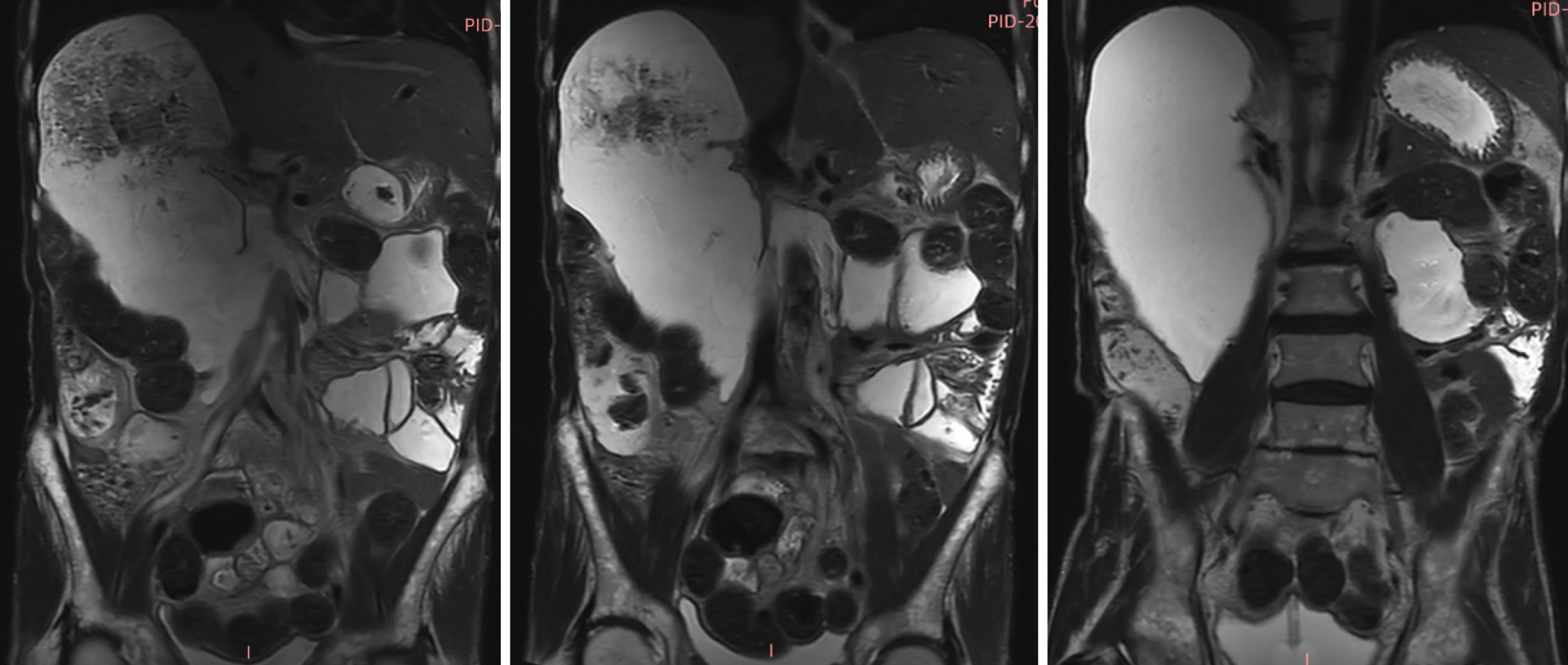

Renal ultrasonography revealed dilation of the left renal collecting system with mild upper ureteral dilatation. Abdominal radiography (Figure 1A) showed right hemidiaphragm elevation and dilated bowel loops with air-fluid levels. The findings of the upper gastrointestinal barium study (Figure 1B) demonstrated mild esophageal dilation, as well as marked duodenal bulb and descending segment dilation with contrast retention. Abdominal CT (Figure 2) revealed duodenal sac-like dilatation with positional changes, narrowing of the horizontal segment, segmental jejunal dilatation, reduced bladder tone, and an indwelling urinary catheter. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 3) revealed significant duodenal and multiple small intestinal dilatations. Gastroscopy revealed reflux esophagitis (LA-B), gastric retention and deformation, and duodenal dilatation with villous atrophy. Colonoscopy revealed a polyp located in the descending colon, which showed an unremarkable anastomotic site.

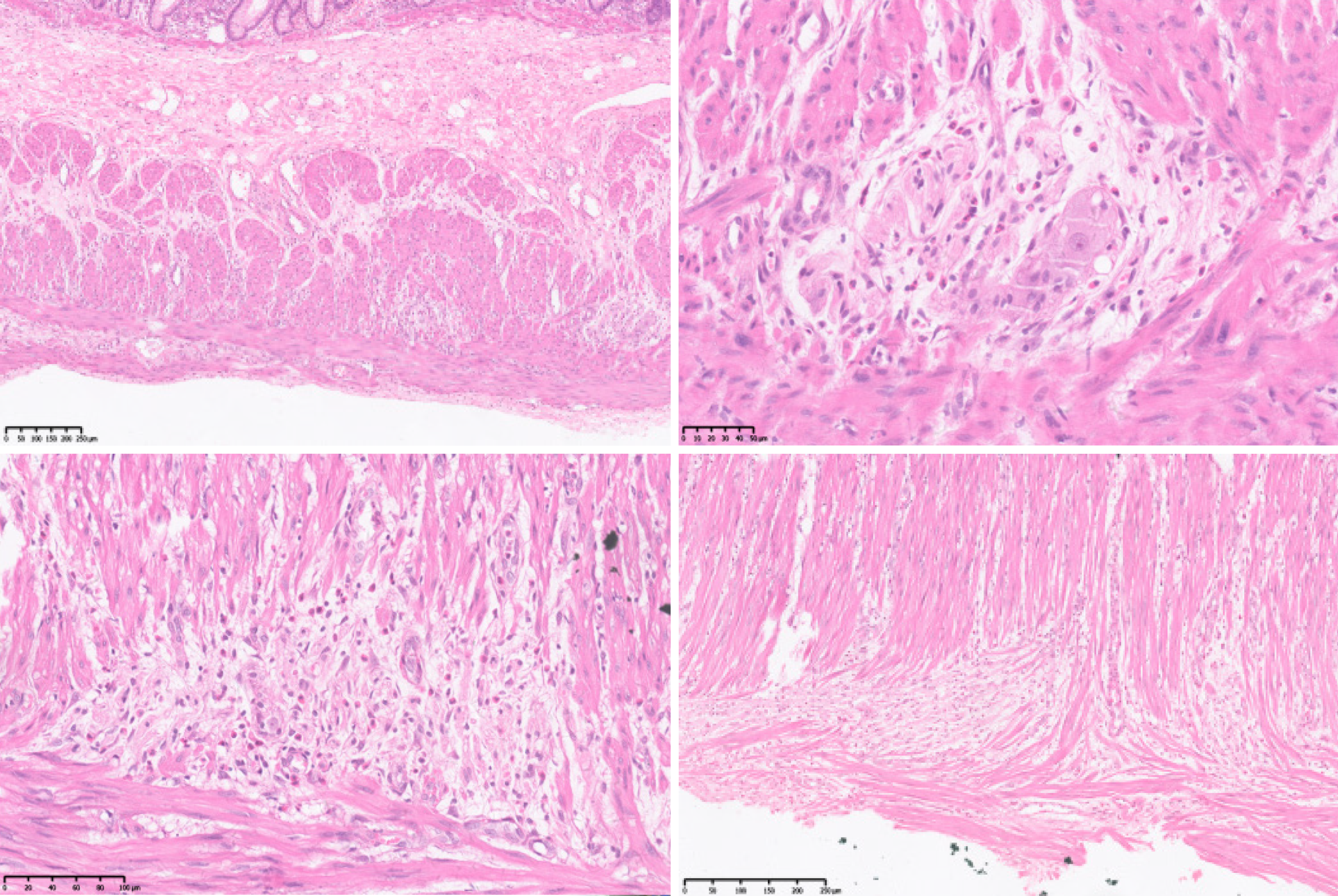

Nerve conduction studies showed that peripheral neuropathy predominantly affected sensory fibers in both lower limbs. A pathological specimen of the resected intestinal segment obtained in 2008 was submitted to the pathology department of our hospital for consultation. The examination revealed muscle fiber atrophy in the muscular layer of the colon, no significant reduction in ganglion cell number, nerve fiber proliferation and disorganization, partial ganglion cell degeneration, or eosinophilic infiltration (Figure 4).

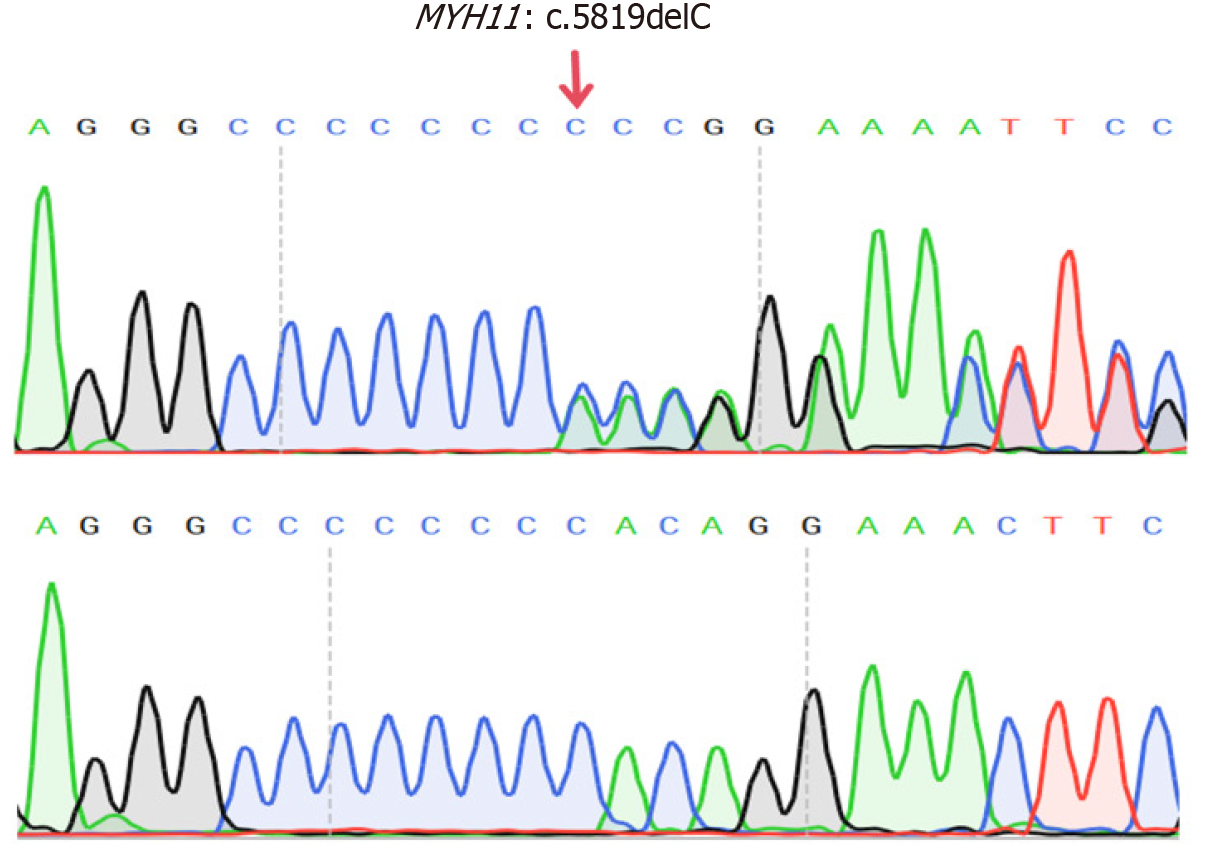

CIPO was diagnosed based on gastrointestinal dysmotility and histopathological findings. Further screening for secondary causes revealed normal glycated HGB levels, thyroid function, and blood cortisol levels. The findings of serum protein and immunofixation electrophoresis, as well as tumor marker levels, were also normal. Antinuclear and anti-double-stranded DNA antibody levels were normal. The celiac disease-related autoantibody panel findings and testing for anti-neuronal antigen antibodies (Ri, Hu, Yo) were negative. Blood tests for tuberculosis infection T-cells, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein–Barr virus were also negative. The hydrogen-methane-carbon dioxide breath test revealed no evidence of bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine. WES identified a heterozygous MYH11 mutation [NM_0010

The patient showed no signs of acute intestinal obstruction and was managed with nutritional support. Given the preserved digestive and absorptive functions, dietary modifications were combined with additional oral enteral nutrition supplementation (1000 mL/day, approximately 1500 kcal). The patient was also administered multivitamins, digestive enzymes, and probiotics.

At the 1- and 3-month follow-ups, the patient’s weight had increased by 1 kg and 3.5 kg, respectively, and the patient showed good compliance and tolerance with enteral nutrition, passing 1–2 soft stools daily.

CIPO is a rare disorder characterized by the severe impairment of gastrointestinal motility, leading to symptoms that mimic mechanical bowel obstruction in the absence of actual luminal blockage[1-3]. It can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, most commonly the small intestine and colon, and may result in severe gastrointestinal dysfunction with potentially life-threatening complications[2-4]. Despite its rarity, CIPO accounts for 15% of pediatric and 9.7% of adult cases of chronic intestinal failure cases[5]. Due to its nonspecific clinical presentation, CIPO is frequently misdiagnosed, with an average diagnostic delay of approximately 8 years[6,7]. The estimated prevalence in adults is approximately 1 per 100000 in males and 0.8 per 100000 in females, with annual incidences of 0.21 per 10000 and 0.24 per 100000 in males and females, respectively[8].

CIPO is a heterogeneous syndrome with multiple etiologies. Based on the pathological findings, this condition can be classified into neuropathic, myopathic, and mesenchymopathic types, with some patients exhibiting mixed features. CIPO can be categorized as hereditary, acquired, or idiopathic. CIPO predominantly affects children and follows autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked inheritance patterns. Acquired CIPO is typically associated with systemic pathophysiological conditions, and is more common in adults. Secondary causes of CIPO include malignancy, neurological disorders, endocrine dysfunction, and connective tissue diseases[9]. The patient in the present case experienced disease onset as an adolescent, with a progressive course over several decades. Despite extensive diagnostic evaluation, no secondary causes were identified. Given these genetic findings, hereditary myopathic CIPO was considered the most likely diagnosis.

Approximately 80% of pediatric pseudo-obstruction cases are hereditary or idiopathic; are often associated with genitourinary involvement, intestinal malrotation, or volvulus; frequently require surgical intervention or parenteral nutrition; and have a poorer prognosis than adult-onset cases[10]. Among them, 56.5% of pediatric patients develop symptoms during the neonatal period, and the incidence gradually decreases with age. Onset during adolescence has also been reported, with an incidence of 9.7%[11]. Currently, most of the reported pathogenic genes associated with pediatric pseudo-obstruction encode proteins related to smooth muscle contraction[12]. In a recent review, Fournier & Fabre summarized the mutation spectrum of genes implicated in visceral myopathy based on the results of 117 reported cases, including 112 postnatal patients and five prenatal terminations. The most frequently mutated genes were actin gamma 2

In the present case, a heterozygous frameshift mutation, MYH11: c.5819del (p.Pro1940HisfsTer91), was identified. This mutation resulted from the deletion of a nucleotide at position 5819 within the gene’s coding sequence, resulting in a frameshift mutation. Consequently, the original stop codon was lost, and a new stop codon was generated at the 91st downstream codon. This led to the addition of 90 extra amino acids at the C-terminus of the MYH11 protein, altering its local three-dimensional structure and contributing to disease pathogenesis[16]. To date, five case reports have identified heterozygous MYH11 mutations in patients with CIPO. In 2019, Dong et al[17] reported on a large 13-member family diagnosed with the CIPO phenotype. Most of the family members presented with megacystis and required long-term self-catheterization. WES analysis of the seven affected individuals revealed a shared MYH11 c.5819del (p.Pro1940

The treatment of patients with CIPO is challenging and requires a multidisciplinary team. Unnecessary surgical interventions should be avoided in adults and children. Management strategies should focus on maintaining adequate fluid and electrolyte status, thereby ensuring sufficient caloric and nutrient intake, promoting intestinal motility coordination, and addressing potential complications such as sepsis and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. The ability to maintain oral intake is a key independent factor for improved survival. Therefore, patients receiving parenteral nutrition should be encouraged to maximize their oral intake as tolerated[20,21]. As this patient presented without acute intestinal obstruction and was in disease remission, the primary treatment approach was dietary adjustments combined with enteral nutrition supplementation.

The role of surgery in CIPO remains controversial. While it can be used to obtain full-thickness intestinal biopsy samples, surgical interventions are generally reserved for emergencies such as severe bowel dilation, perforation, or ischemia. In one 13-year longitudinal study enrolling 59 adult patients with idiopathic CIPO, 88% were reported to have undergone an average of three unnecessary surgeries, highlighting the significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges associated with this condition[6]. Another retrospective study of 63 adult patients reported an overall postoperative mortality rate of 7.9% and a 66% reoperation rate within 5 years due to CIPO-related complications[22,23]. For patients with end-stage CIPO, isolated small bowel transplantation or multivisceral transplantation may be considered as treatment options[24,25]. Although the patient in the present case underwent full-thickness intestinal histopathology in 2008, a definitive diagnosis was not made at that time because of the limited awareness of CIPO among physicians. Consequently, several decades passed before the patient finally received an accurate diagnosis.

In conclusion, CIPO is a rare condition leading to severe impairments of gastrointestinal motility. Owing to the limited awareness of this condition among clinicians, misdiagnosis, missed diagnosis, and inappropriate treatment are common. This case involved an older male with insidious onset in adolescence, and a disease course spanning several decades before a definitive diagnosis could be established. WES identified a rare heterozygous MYH11 mutation, confirming hereditary myopathic CIPO. Overall, this case suggests that inherited conditions can be diagnosed even in older patients.

We wish to express our gratitude to the patient and his family.

| 1. | Stanghellini V, Corinaldesi R, Barbara L. Pseudo-obstruction syndromes. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1988;2:225-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | De Giorgio R, Cogliandro RF, Barbara G, Corinaldesi R, Stanghellini V. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: clinical features, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011;40:787-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gabbard SL, Lacy BE. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Nutr Clin Pract. 2013;28:307-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yeung AK, Di Lorenzo C. Primary gastrointestinal motility disorders in childhood. Minerva Pediatr. 2012;64:567-584. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Pironi L, Corcos O, Forbes A, Holst M, Joly F, Jonkers C, Klek S, Lal S, Blaser AR, Rollins KE, Sasdelli AS, Shaffer J, Van Gossum A, Wanten G, Zanfi C, Lobo DN; ESPEN Acute and Chronic Intestinal Failure Special Interest Groups. Intestinal failure in adults: Recommendations from the ESPEN expert groups. Clin Nutr. 2018;37:1798-1809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Stanghellini V, Cogliandro RF, De Giorgio R, Barbara G, Morselli-Labate AM, Cogliandro L, Corinaldesi R. Natural history of chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction in adults: a single center study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:449-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stanghellini V, Cogliandro RF, de Giorgio R, Barbara G, Salvioli B, Corinaldesi R. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: manifestations, natural history and management. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:440-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Iida H, Ohkubo H, Inamori M, Nakajima A, Sato H. Epidemiology and clinical experience of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction in Japan: a nationwide epidemiologic survey. J Epidemiol. 2013;23:288-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhu CZ, Zhao HW, Lin HW, Wang F, Li YX. Latest developments in chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:5852-5865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Thapar N, Saliakellis E, Benninga MA, Borrelli O, Curry J, Faure C, De Giorgio R, Gupte G, Knowles CH, Staiano A, Vandenplas Y, Di Lorenzo C. Paediatric Intestinal Pseudo-obstruction: Evidence and Consensus-based Recommendations From an ESPGHAN-Led Expert Group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:991-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Muto M, Matsufuji H, Tomomasa T, Nakajima A, Kawahara H, Ida S, Ushijima K, Kubota A, Mushiake S, Taguchi T. Pediatric chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction is a rare, serious, and intractable disease: a report of a nationwide survey in Japan. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:1799-1803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nham S, Nguyen ATM, Holland AJA. Paediatric intestinal pseudo-obstruction: a scoping review. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181:2619-2632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fournier N, Fabre A. Smooth muscle motility disorder phenotypes: A systematic review of cases associated with seven pathogenic genes (ACTG2, MYH11, FLNA, MYLK, RAD21, MYL9 and LMOD1). Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2022;11:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bianco F, Lattanzio G, Lorenzini L, Mazzoni M, Clavenzani P, Calzà L, Giardino L, Sternini C, Costanzini A, Bonora E, De Giorgio R. Enteric Neuromyopathies: Highlights on Genetic Mechanisms Underlying Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction. Biomolecules. 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gauthier J, Ouled Amar Bencheikh B, Hamdan FF, Harrison SM, Baker LA, Couture F, Thiffault I, Ouazzani R, Samuels ME, Mitchell GA, Rouleau GA, Michaud JL, Soucy JF. A homozygous loss-of-function variant in MYH11 in a case with megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:1266-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gilbert MA, Schultz-Rogers L, Rajagopalan R, Grochowski CM, Wilkins BJ, Biswas S, Conlin LK, Fiorino KN, Dhamija R, Pack MA, Klee EW, Piccoli DA, Spinner NB. Protein-elongating mutations in MYH11 are implicated in a dominantly inherited smooth muscle dysmotility syndrome with severe esophageal, gastric, and intestinal disease. Hum Mutat. 2020;41:973-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dong W, Baldwin C, Choi J, Milunsky JM, Zhang J, Bilguvar K, Lifton RP, Milunsky A. Identification of a dominant MYH11 causal variant in chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: Results of whole-exome sequencing. Clin Genet. 2019;96:473-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li N, Song YM, Zhang XD, Zhao XS, He XY, Yu LF, Zou DW. Pseudoileus caused by primary visceral myopathy in a Han Chinese patient with a rare MYH11 mutation: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:12623-12630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Geraghty RM, Orr S, Olinger E, Neatu R, Barroso-Gil M, Mabillard H; Consortium GER; Wilson I, Sayer JA. Use of whole genome sequencing to determine the genetic basis of visceral myopathies including Prune Belly syndrome. J Rare Dis (Berlin). 2023;2:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pironi L, Arends J, Bozzetti F, Cuerda C, Gillanders L, Jeppesen PB, Joly F, Kelly D, Lal S, Staun M, Szczepanek K, Van Gossum A, Wanten G, Schneider SM; Home Artificial Nutrition & Chronic Intestinal Failure Special Interest Group of ESPEN. ESPEN guidelines on chronic intestinal failure in adults. Clin Nutr. 2016;35:247-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 54.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Joly F, Amiot A, Messing B. Nutritional support in the severely compromised motility patient: when and how? Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011;40:845-851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Murr MM, Sarr MG, Camilleri M. The surgeon's role in the treatment of chronic intestinal pseudoobstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:2147-2151. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Sabbagh C, Amiot A, Maggiori L, Corcos O, Joly F, Panis Y. Non-transplantation surgical approach for chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: analysis of 63 adult consecutive cases. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:e680-e686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lindberg G. Pseudo-obstruction, enteric dysmotility and irritable bowel syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;40-41:101635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Grant D, Abu-Elmagd K, Mazariegos G, Vianna R, Langnas A, Mangus R, Farmer DG, Lacaille F, Iyer K, Fishbein T; Intestinal Transplant Association. Intestinal transplant registry report: global activity and trends. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:210-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |