Published online Mar 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i3.966

Peer-review started: December 19, 2023

First decision: January 4, 2024

Revised: January 20, 2024

Accepted: February 25, 2024

Article in press: February 25, 2024

Published online: March 27, 2024

Processing time: 93 Days and 22.3 Hours

Colorectal cavernous hemangioma is a rare vascular malformation resulting in recurrent lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and can be misinterpreted as colitis. Surgical resection is currently the mainstay of treatment, with an emphasis on sphincter preservation.

We present details of two young patients with a history of persistent hema

Multiple sequential EUS-guided injections of lauromacrogol is a safe, effective, cost-efficient, and minimally invasive alternative for colorectal cavernous he

Core Tip: Colorectal cavernous hemangioma is a rare vascular malformation resulting in recurrent lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. We present details of two young patients diagnosed with colorectal cavernous hemangioma by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). Cavernous hemangioma was relieved by EUS-guided lauromacrogol injection and the patients achieved favorable clinical prognosis. Surgical resection is currently the mainstay treatment for colorectal cavernous hemangioma, but EUS-guided lauromacrogol injection might be a better option.

- Citation: Zhu HT, Chen WG, Wang JJ, Guo JN, Zhang FM, Xu GQ, Chen HT. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided lauromacrogol injection for treatment of colorectal cavernous hemangioma: Two case reports. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(3): 966-973

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i3/966.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i3.966

Colorectal cavernous hemangioma is an uncommon benign vascular neoplasm that usually present at birth. Anemia and painless lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding are the most common presenting symptoms. Some patients present with abdominal pain, diarrhea and constipation, or remain asymptomatic[1]. Routine evaluation includes endoscopic exa

To date, management is still dominated by surgery, especially for patients with a wide range of lesions, and complete resection is an effective method to cure and pathologically confirm the disease[6]. However, for patients with a single lesion or in cases an extensive resection is not feasible or in patients who refuse surgical intervention, nonoperative endoscopic treatment can be considered, such as sclerotherapy, electrocoagulation, or metal clipping for hemostasis[7]. Only a few data are available on sclerotherapy of colorectal cavernous hemangioma. EUS-guided lauromacrogol injection to cure the disease has not been reported previously.

We report two cases of colorectal cavernous hemangioma successfully diagnosed by EUS, and treated by multiple sequential EUS-guided lauromacrogol injections. Clinical features and pathophysiology are discussed and a brief review of the current literature regarding colorectal cavernous hemangioma is included.

Case 1: A 20-year-old man was admitted to our hospital for recurrent hematochezia for > 7 years, presenting with worsening painless fresh rectal bleeding for 1 month.

Case 2: A 26-year-old man with a history of increased stool frequency and intermittent hematochezia for > 1 year.

Case 1: Seven years previously, the patient began to have bloody stools without fever, abdominal distending pain, nausea and vomiting, or anal heaviness, and had been misdiagnosed with internal hemorrhoids, ulcerative proctitis, ischemic bowel disease and angiodysplasia in local hospitals. He had 1 month history of worsening painless fresh rectal bleeding before hospitalization.

Case 2: In the year before hospital admission, the patient developed increased stool frequency and intermittent bloody stools without abdominal pain, diarrhea, mucus, pus, or other symptoms. He attended our hospital and underwent colo

Case 1: The patient underwent endoscopic ligation of hemorrhoids 5 years previously.

Case 2: There was no significant personal or family history.

Case 1: The patient had no history of systemic syndromes such as Osler Weber Rendu and blue rubber bleb nevus syn

Case 2: There was no significant personal or family history.

Case 1: On physical examination, the patient had an anemic appearance but the rest of the examination was unre

Case 2: No obvious abnormalities were observed.

Case 1: Laboratory findings revealed microcytic hypochromic anemia with hemoglobin level of 6.4 g/dL (normal range 11.3 g/dL–15.1 g/dL). Other laboratory data showed no abnormalities.

Case 2: Stool occult blood examination was weakly positive. Other laboratory data showed no abnormalities.

Case 1: CT revealed diffuse thickening of the rectum with multiple calcification foci representing phleboliths, indicating vascular anomalies. And the enhanced rectal wall was not obvious in CT arterial phase (Figure 1). Endoscopic exami

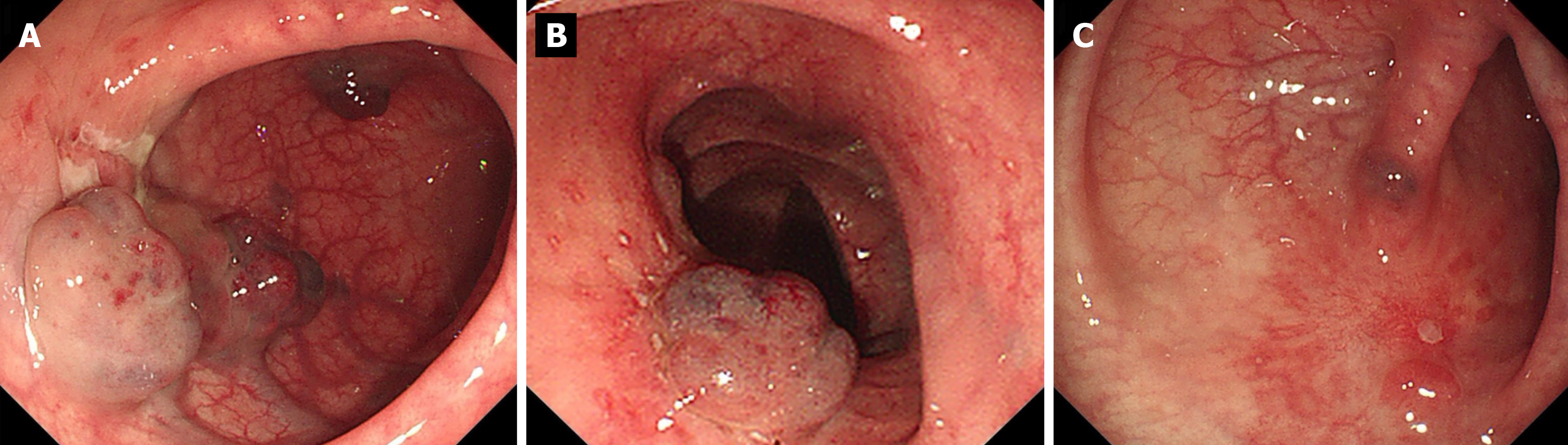

Case 2: Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT showed thickening of the proximal sigmoid colon wall with phleboliths. Colonoscopy showed multiple bluish-purple nodules limited to the proximal sigmoid, with a maximum size of 3.0 cm × 4.0 cm, and several isolated vascular masses were seen nearby (Figure 3A). Radial US scanning revealed nonechoic va

Taking into consideration the clinical history, CT scan, endoscopic visualization of a blood-filled hemangioma, EUS demonstrated the sponge-like nature of the malformation, and a diagnosis of rectal cavernous hemangioma was made.

Combination of clinical history, EUS findings, and CT scan led to a diagnosis of colorectal cavernous hemangioma.

Although surgical excision of the tumor is the only curative approach and the main determinant of prognosis, the patient declined any further surgical intervention because the lesion was close to the anus. With EUS guidance, a standard 22-gauge fine aspiration needle was inserted into the dilated vessels and 7 mL lauromacrogol was injected into the vessel, which generated hyperechoic clots in the lesion area (Video). EUS showed hyperechoic filling in the vascular lumen after injection (Figure 4A), and color Doppler US showed that the blood flow signal disappeared (Figure 4B). We chose another two points by intravascular injection of 9.5 mL and 10 mL lauromacrogol and achieved a similar effect to the previous endoscopic treatment. Colonoscopy showed that the elevated vascular mass was relieved and no obvious bleeding at the injection site (Figure 4C). He received antibiotics for 24 h and started to eat 12 h later and was discharged successfully.

Under EUS guidance, a 22-gauge fine aspiration needle was inserted into the dilated vessels, and 30 mL lauromacrogol was injected into the vessel generating hyperechoic clots in the lesion area, and the lesion became pale and collapsed. There was no fever, abdominal distension, abdominal pain, hematemesis, black stool or other symptoms after the ope

Lauromacrogol injection significantly improved hematochezia symptoms, but the patient experienced refractory consti

In the following 2 months, the patient received endoscopic re-examination and EUS-guided sclerotherapy injection once a month, and the size and scope of the hemangiomas were significantly reduced (Figure 5A and B). At the fourth re-exa

Colorectal hemangioma is an exceedingly rare congenital benign vascular disorder. The primary pathological subtypes encompass cavernous, capillary, and mixed forms, with cavernous hemangioma being the most prevalent. Cavernous hemangiomas can be further classified as localized or diffuse types, characterized by enlarged blood-filled spaces lined with abnormally thin vessel walls[8]. Additionally, certain systemic syndromes such as Osler Weber Rendu and blue rubber bleb nevus syndromes may present histologically as telangiectatic, mixed or cavernous hemangiomas in the in

Colorectal cavernous hemangioma was first elucidated in 1839 but its pathogenesis is still not fully understood. This infrequent benign GI vascular lesion is considered to be a type of venous malformation that might be caused by the ab

The preoperative diagnosis rate of this disease is low, and the lesion is usually found during enteroscopy, but the final diagnosis still needs to rely on postoperative pathological examination. Histologically, there are characteristic features but endoscopic biopsy should be avoided because of the high risk of severe hemorrhage. Clinical diagnosis of colorectal ca

Complete surgical resection is currently considered the only effective way to cure the disease. Conservative options like banding and sclerotherapy have been reported, and they can decrease the amount and frequency of colorectal he

Here, we report two cases of diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectosigmoid that was successfully treated by novel EUS-guided lauromacrogol injection, which achieved good clinical prognosis. Under the EUS guidance, the needle is accurately inserted into the cavernous hemangioma for the injection of lauromacrogol. The filling of lauromacrogol inside the hemangioma can be observed in real time during the EUS scan. During the operation, the injection can be stopped when the lesion is full of high echo of lauromacrogol. It can not only effectively reduce the risk of extravascular injection caused by "blind" injection under the direct vision of ordinary endoscope, but also monitor the changes of the echo in the hemangioma cavity during the injection process, and accurately control the injection amount of lauromacrogol. However, the local lesions may not penetrate completely due to the dilution of lauromacrogol with the blood flow after a single injection of lauromacrogol. Therefore, sequential treatment should be performed as appropriate. If the lesions are still residual in the follow-up, supplementary injection of sclerosing agent can be performed again. Compared with other non-surgical conservative treatment methods, EUS-guided injection of lauromacrogol in the treatment of colorectal cavernous hemangioma is more targeted and thorough, with fewer intraoperative and postoperative complications.

These cases present a novel method of sclerotherapy under EUS guidance for colorectal cavernous hemangioma, suggesting that EUS could play a greater role in the interventional therapy of digestive cavernous hemangioma. The EUS-guided injection of lauromacrogol for treatment of colorectal cavernous hemangioma is a safe, effective, cost-efficient, and minimally invasive technique, especially in instances where an extensive resection is not feasible or not tolerant for the patients. Multiple sequential EUS-guided injections of lauromacrogol can provide benefits to patients and reduce the likelihood of recurrence. However, long-term therapeutic effects and recurrence rates still require further follow-up and observation. Moreover, well-designed prospective studies are needed to evaluate the safety and feasibility of EUS-guided lauromacrogol injection in the treatment of GI hemangiomas, with particular consideration given to long-term follow-up. In the future, more cases should enable exploration of the potential of endoscopic therapy in curing GI hemangiomas and improving postoperative quality of life.

Our cases show the safety and feasibility of EUS-guided lauromacrogol injection as an appropriate therapeutic option for colorectal cavernous hemangioma. It avoids surgery in some patients, but surveillance and repeated treatment are deemed necessary because of the likelihood of further lesions later in life.

We sincerely appreciate the patients and their families for their cooperation in information acquisition, treatment, and follow-up.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Okasha H, Egypt; Sugimoto M, Japan S-Editor: Luo ML L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu ZH

| 1. | Castro-Poças F, Lobo L, Amaro T, Soares J, Saraiva MM. Colon hemangiolymphangioma--a rare case of subepithelial polyp. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:989-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chatu S, Kumar D, Du Parcq J, Vlahos I, Pollok R. A rare cause of rectal bleeding masquerading as proctitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e99-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Amarapurkar D, Jadliwala M, Punamiya S, Jhawer P, Chitale A, Amarapurkar A. Cavernous hemangiomas of the rectum: report of three cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1357-1359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kusunoki R, Fujishiro H, Kitagawa K, Kinoshita Y, Ishihara S. Diffuse cavernous hemangiolymphangioma of the rectosigmoid, diagnosed by contrast-enhanced EUS. VideoGIE. 2020;5:375-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sharma M, Adulqader A, Shifa R. Endoscopic ultrasound for cavernous hemangioma of rectum. Endosc Ultrasound. 2014;3:63-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jackson CS, Gerson LB. Management of gastrointestinal angiodysplastic lesions (GIADs): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:474-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yoo S. GI-Associated Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:193-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Regula J, Wronska E, Pachlewski J. Vascular lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:313-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nosher JL, Murillo PG, Liszewski M, Gendel V, Gribbin CE. Vascular anomalies: A pictorial review of nomenclature, diagnosis and treatment. World J Radiol. 2014;6:677-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Marchuk DA. Pathogenesis of hemangioma. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:665-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lyon DT, Mantia AG. Large-bowel hemangiomas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27:404-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ghartimagar D, Ghosh A, Shrestha MK, Timilsina BD, Thapa S, Talwar O. Diffuse vascular malformation of large intestine clinically and radiologically misdiagnosed as ulcerative colitis. J Surg Case Rep. 2017;2017:rjx016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fair L, Gough B, Oknokwo A, Stadler R. A giant hemangioma of the sigmoid colon as a cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding in a young man. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2022;35:852-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hsu RM, Horton KM, Fishman EK. Diffuse cavernous hemangiomatosis of the colon: findings on three-dimensional CT colonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1042-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kandpal H, Sharma R, Srivastava DN, Sahni P, Vashisht S. Diffuse cavernous haemangioma of colon: magnetic resonance imaging features. Report of two cases. Australas Radiol 2007; 51 Spec No. : B147-B151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Djouhri H, Arrivé L, Bouras T, Martin B, Monnier-Cholley L, Tubiana JM. MR imaging of diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectosigmoid colon. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:413-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sami SS, Al-Araji SA, Ragunath K. Review article: gastrointestinal angiodysplasia - pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:15-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zeng Z, Wu X, Chen J, Luo S, Hou Y, Kang L. Safety and Feasibility of Transanal Endoscopic Surgery for Diffuse Cavernous Hemangioma of the Rectum. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019;2019:1732340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |