Published online Apr 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i4.1660

Peer-review started: December 17, 2023

First decision: January 10, 2024

Revised: January 16, 2024

Accepted: February 20, 2024

Article in press: February 20, 2024

Published online: April 15, 2024

Processing time: 115 Days and 15.5 Hours

Gastric cancer (GC) is a significant health problem worldwide, and early detection and accurate diagnosis are crucial for improving patient outcomes. Crawling-type gastric adenocarcinoma is a rare subtype of GC that has unique histopathological and clinical characteristics, and its diagnosis and management can be challenging. This pathological type of GC is also rare.

Here, we report the case of a patient who underwent ordinary endoscopy, na

The “crawling-type” GC is a rare and specific tumor pathology. It is difficult to identify and diagnose gliomas via endoscopy. The tumor is ill-defined, with a flat appearance and indistinct borders due to the lack of contrast against the background mucosa. Pathology revealed that the tumor cells were hand-like, so the patient has diagnosed with “crawling-type” gastric adenocarcinoma.

Core Tip: “Crawling type” gastric cancer is a rare variant of early gastric cancer. It was once called “Shaking-Hands Struc

- Citation: Xu YW, Song Y, Tian J, Zhang BC, Yang YS, Wang J. Clinical pathological characteristics of “crawling-type” gastric adenocarcinoma cancer: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(4): 1660-1667

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i4/1660.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i4.1660

Gastric cancer (GC) is a major public health issue worldwide. The annual incidence of GC in China accounts for more than 40% of the total number of GC deaths worldwide[1]. An increase in the incidence of GC seriously impacts people’s quality of life. According to the World Health Organization, GC tissue types can usually be divided into four types. The first type is called adenocarcinoma and includes papillotubular, tubular gland, and mucus adenocarcinoma. The most common tissue pathological subtype is tube-shaped cancer, which is divided into highly differentiated or neutralized adenocarcinoma[2]. The second is called undifferentiated cancer. The third type is called mucous cancer and is also known as printing cell carcinoma. The special types of cancer include glandular squamous cell carcinoma, squamous cell cancer, and cancer. However, this type of crawling-type gastric adenocarcinoma was not recorded.

“Crawling type” GC is an uncommon type of early GC that accounts for 2%-3% of early GCs[3]. It was once called the “shaking-hand structure”, “WHYX pattern”, or “shaking-hand pattern”, and it is an important subtype of gastric gland cancer[4]. It is also difficult to diagnose. Endoscopically, the tumor is ill-defined, with a flat appearance and indistinct borders due to the lack of contrast against the background mucosa[5]. As a result, early diagnosis of the disease might be challenging. Positive lateral margins and high rates of incomplete resection are common outcomes of endoscopic resection.

Early detection and treatment of GC, including the type of crawling, is important for improving patient outcomes. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) treatment and pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of crawling-type GC. This highlights the importance of using a combination of diagnostic tools and techniques to accurately diagnose this type of GC. Therefore, we encountered “crawling type” GC, which proved challenging for endoscopic diagnosis. This case mainly describes the diagnosis, endoscopic features, and pathological characteristics of “crawling type” GC.

We hope that, through this case, we can improve clinicians’ understanding of GC pathology and enrich clinical experience and treatment. This approach is conducive to clinical treatment. Continued research and collaboration among healthcare professionals are essential for improving GC diagnosis and treatment.

A male, 72 years old. No physical discomfort, a physical examination, and gastroscopy are required.

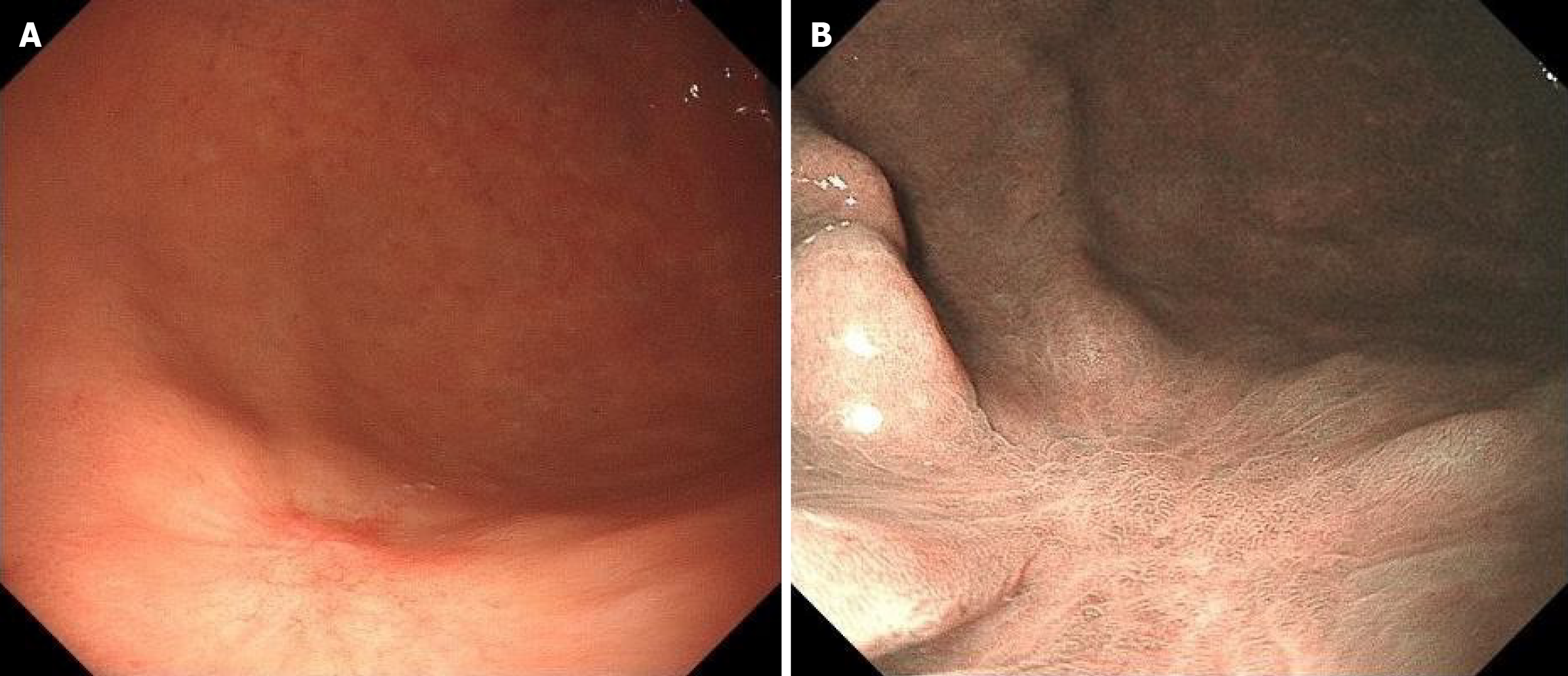

Due to a regular physical examination, the gastroscopy found that the lower end of the stomach was marked with shallow depression near the antrum, with surface flushing and a tuberosity bulge in the centre (Figure 1A). Then a biopsy. The indigo carmine staining is shallow depression, and the surrounding boundary is clear (Figure 1B). Consider the patient’s atrophic gastritis with gastric antrum erosion and gastric antrum body junction lesions.

In the past medical history of patients, he had a history of hypertension and diabetes. Now blood pressure and blood glucose are perennial oral drug control. They denied others the history of chronic diseases, and the history of infectious diseases such as hepatitis, tuberculosis, and schistosomiasis.

The patient denied any family history of malignant tumours. There is no history of Helicobacter pylori infection.

Physical examination revealed no fever, heart rate 77 bpm, blood pressure 141/85 mmHg, and other examinations all have discomfort.

After admission, the patient improved the examination of tumour indicators, and the results were negative (Table 1).

| Laboratory tests | Result | Reference values |

| Pro-GRP | 54.60 | 28.3-65.7 pg/mL |

| AFP | 3.47 | 0-7.0 ng/mL |

| CEA | 3.79 | 0-6.5 ng/mL |

| CA19-9 | 12.60 | 0-27.0 U/mL |

| CA72-4 | 5.43 | 0-6.9 U/mL |

No obvious abnormality in the upper abdominal enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed no concurrent lymph node and distant metastasis (Figure 2A).

Pathology revealed high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia in the mucosa. The patient was subsequently examined after admission. Narrow-band imaging (NBI) after admission revealed a station membrane hyperemia lesion on the posterior wall of the gastric antrum. The staining showed that the lesion was a shallow depression with an unclear boundary. At the outer layer of the tumor, the micro glandular tube structure was disorganized and variable in size. The microvessels were slightly tortuous and expanded, forming a bright boundary with the periphery, with an endoscopic lesion ranging from 5 mm × 6 mm (Figure 3).

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) was used to determine the source of the stomach wall. The local area is slightly thickened, the other levels of the stomach wall are continuous and complete, and there are no obvious abnormal echoes. The diagnosis was that the lesion was in the gastric mucosa (Figure 2B).

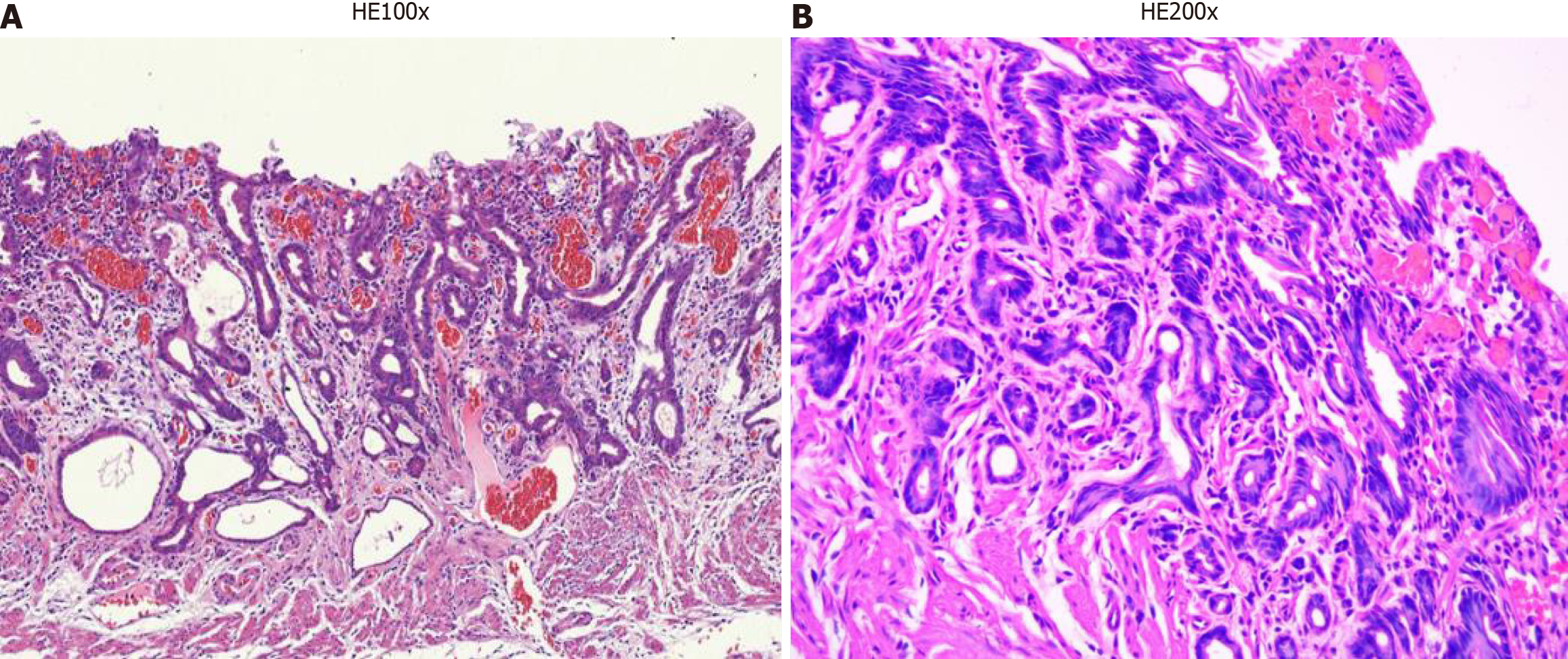

Immunohistochemical examination revealed Ki-67 positivity in tissue (Figure 4A), partial MUC2 positivity (Figure 4B), partial MUC5AC negativity (Figure 4C) and partial MUC6 positivity (Figure 4D). Hematoxylin and eosin were detected (Figure 5), after which poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma cells were detected.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed that the lesions were at the level of the neck of the gland and continued with the surface epithelium. Determining the tumor boundaries is difficult. There were “crawling type” glands everywhere in the tumour’s vicinity. Moreover, it spreads laterally in the lamina propria, but not in the stomach glands.

The final diagnosis was crawling-type gastric adenocarcinoma.

Considering that the lesion was in the mucosa, ESD was performed. After circumferential marking along the normal mucosa around the lesion, submucosal injection was performed to lift the lesion, and the nonlifting sign was negative. Then, the FLUSH knife was used to perform a circumferential incision along the normal mucosa at the outer edge of the lesion marker point. Submucosal dissection was performed along the submucosa until the lesion was completely stripped and resected. The resected lesion was recovered and sent for pathological examination. A well-to-moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma that was limited to the mucosa was observed. No vascular or lymphatic invasion was found upon histological investigation. It was restricted to the submucosa and was restricted to the deeper lesion. Both the horizontal and vertical margins were negative.

The patient was subsequently followed up for one year without any additional treatment (Figure 6).

Gastric “crawling-type” adenocarcinoma is a tumor that typically spreads laterally within the mucosa and is histologically characterized by irregularly united glands with low-grade cellular atypia. Initially, it was classified as a neoplasm with “mimicking intestinal metaplasia” by Endoh et al[6], and subsequently, Yao et al[7] reported 9 additional cases of “extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinoma”.

There are many pathological types of GC. Gastric “crawling-type” adenocarcinoma is a special pathological type of cancer. Low-grade nuclear atypia and morphology resembling intestinal metaplasia with a laterally spreading pattern were its defining features. The “crawling type” of the stomach is known as one of the characteristics of extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinomas[8].

The tumor exhibits poorly fused glands and low-grade cellular atypia, which are histologically distinguished by a tendency to migrate laterally within the mucosa. Because they are in the mucosal layer, they are difficult to find by general endoscopy; usually, they are shallow lesions (Figure 1), and it is easy to miss the diagnosis. Pathology was only described in previous cases. This case not only described the pathological characteristics of the patients but also described the characteristics of gastric “crawling-type” adenocarcinoma from the realization of imaging and EUS.

After admission, there was no obvious abnormality in the tumor index (Table 1) or upper abdominal enhanced CT (Figure 2A). EUS revealed that the lesion was in the mucosal layer without submucosal infiltration or lymph node metastasis (Figure 2B). Chromoendoscopy, magnifying endoscopy, and NBI were routinely used to determine that the structure of the gastric mucosal gland duct was disrupted and that the boundary around the tumor was clear (Figure 3). The tumor in question was a superficial depressed (IIc) type that was in the middle third of the stomach of this patient. NBI and indigo carmine staining revealed that the tumor borders were quite well-defined. The tumor graft called “crawl” cannot be detected in the superficial layer but can be detected in the epithelial proliferative zone. This characteristic may be attributed to the fact that gastric “crawling-type” adenocarcinoma glands “crawl” into the epithelial proliferative zone where they are often at least partly covered by non-neo-plastic foveolar epithelium.

These traits are visible in the irregularly fused glands. However, due to the exceedingly low degree of cellular atypia, approximately 50% of the initial biopsies are misinterpreted as either inconclusive for neoplasia or reactive intestinal metaplasia[9,10]. Pathologists use structural atypia for diagnosing this kind of GC in hospitals and clinics. It is challenging to identify “crawling type” GCs endoscopically. Extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinomas are frequently found in the middle third of the stomach[7]. Due to the surface, flat or superficial depression of the tumor can occur, as can the presence of hazy edges. Gland tube disorders of the lesion were also observed. These characteristics demonstrate a discrepancy between endoscopic and pathological examinations, which can lead to misdiagnosis.

It is difficult to identify cellular atypia through histological exams; therefore, pathologists should make a diagnosis based on structural atypia. This type of lesion frequently results in false diagnoses of benign lesions such as intestinal metaplasia[11]. The most accurate method for diagnosing “crawling-type” cancer is pathology. Except for the surface layer, most tumor glands had significant MUC6 immunohistochemical positivity. MUC5AC is expressed in both the deeper and superficial layers, with a tendency toward positivity in the former. In this case, MUC5AC was negative. MUC2 expression is generally negative in these tumors[12]. Ki-67 (partially positive) was also detected (Figure 4). Changes in cell structure can be observed by HE staining for diagnosis. Therefore, according to the pathological diagnosis, irregularly fused glands are the most important diagnostic clue for “crawling type” GC. The shapes of the letters “H”, “X”, “W”, and “Y” are recreated by the pattern of the fused glands with architectural traits such as branching, anastomosing, distention, abortive and spiky forms, glandular overgrowth, and discohesive neoplastic cells[3] (Figure 5). The shapes of the letters “H”, “X”, “W”, and “Y” are recreated by the pattern of the fused glands with architectural traits such as branching, anastomosing, distention, abortive and spiky forms, glandular overgrowth, and discohesive neoplastic cells. Therefore, to identify abnormally fused glands in deeper sites, biopsies from all layers of mucosal tissue, not just the upper mucosal tissue, need to be collected. After the patient was discharged from the hospital, a regular gastroscopy was performed, and no tumor recurrence was found (Figure 6).

In conclusion, we described a patient with a “crawling type” of GC that was found by ESD therapy, despite being extremely difficult to identify preoperatively. Due to the lack of symptoms in the earliest phases of this disease, endoscopic and histological diagnosis of this kind of GC is difficult. A thorough examination combined with many mucosal layer biopsies and a repeat biopsy is essential for obtaining a correct diagnosis. This variation is something to consider, particularly if we notice a superficial flat-type or superficially depressed tumor in the middle of the stomach.

We sincerely appreciate the patient and her family for their cooperation in information acquisition, treatment, and follow-up.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology & hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fazilat-Panah D, Iran S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55833] [Article Influence: 7976.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 2. | Ahadi M, Sokolova A, Brown I, Chou A, Gill AJ. The 2019 World Health Organization Classification of appendiceal, colorectal and anal canal tumours: an update and critical assessment. Pathology. 2021;53:454-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Okamoto N, Kawachi H, Yoshida T, Kitagaki K, Sekine M, Kojima K, Kawano T, Eishi Y. "Crawling-type" adenocarcinoma of the stomach: a distinct entity preceding poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:220-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Woo HY, Bae YS, Kim JH, Lee SK, Lee YC, Cheong JH, Noh SH, Kim H. Distinct expression profile of key molecules in crawling-type early gastric carcinoma. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:612-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kase S, Osaki M, Honjo S, Adachi H, Ito H. Tubular adenoma and intramucosal intestinal-type adenocarcinoma of the stomach: what are the pathobiological differences? Gastric Cancer. 2003;6:71-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Endoh Y, Tamura G, Motoyama T, Ajioka Y, Watanabe H. Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma mimicking complete-type intestinal metaplasia in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:826-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yao T, Utsunomiya T, Oya M, Nishiyama K, Tsuneyoshi M. Extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2510-2516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ushiku T, Arnason T, Ban S, Hishima T, Shimizu M, Fukayama M, Lauwers GY. Very well-differentiated gastric carcinoma of intestinal type: analysis of diagnostic criteria. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:1620-1631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Niimi C, Goto H, Ohmiya N, Niwa Y, Hayakawa T, Nagasaka T, Nakashima N. Usefulness of p53 and Ki-67 immunohistochemical analysis for preoperative diagnosis of extremely well-differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118:683-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kang KJ, Kim KM, Kim JJ, Rhee PL, Lee JH, Min BH, Rhee JC, Kushima R, Lauwers GY. Gastric extremely well-differentiated intestinal-type adenocarcinoma: a challenging lesion to achieve complete endoscopic resection. Endoscopy. 2012;44:949-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Joo M, Han SH. Gastric-Type Extremely Well-Differentiated Adenocarcinoma of the Stomach: A Challenge for Preoperative Diagnosis. J Pathol Transl Med. 2016;50:71-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kushima R, Vieth M, Borchard F, Stolte M, Mukaisho K, Hattori T. Gastric-type well-differentiated adenocarcinoma and pyloric gland adenoma of the stomach. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:177-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |