Published online Mar 15, 2022. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v14.i3.724

Peer-review started: November 1, 2021

First decision: December 2, 2021

Revised: December 15, 2021

Accepted: February 27, 2022

Article in press: February 27, 2022

Published online: March 15, 2022

Processing time: 129 Days and 0.4 Hours

The use of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has been reported in the treatment of gastric low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (LGIN). However, its efficacy and prognostic risk factors have not been well analyzed.

To explore the efficacy and prognostic risk factors of RFA for gastric LGIN in a large, long-term follow-up clinical study.

The clinical data of 271 consecutive cases from 198 patients who received RFA for treatment of gastric LGIN at the Chinese PLA General Hospital from October 2014 to October 2020 were reviewed in this retrospective study. Data on operative parameters, complications, and follow-up outcomes including curative rates were recorded and analyzed.

The curative rates of endoscopic RFA for gastric LGIN at 3 mo, 6 mo, and 1-5 years after the operation were 93.3%, 92.8%, 91.5%, 90.3%, 88.5%, 85.7%, and 83.3%, respectively. Multivariate analyses revealed that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and disease duration > 1 year had a significant effect on the curative rate (P < 0.001 and P = 0.013, respectively). None of patients had bleeding, perforation, infection, or other serious complications after RFA, and the main discomfort was postoperative abdominal pain.

RFA was safe and effective for gastric LGIN during long-term follow-up. H. pylori infection and disease course > 1 year may be the main risk factors for relapse of LGIN after RFA.

Core Tip: This is a retrospective study to explore the efficacy and prognostic risk factors of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for gastric low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (LGIN). The curative rates of endoscopic RFA for gastric LGIN at 3 mo, 6 mo, and 1-5 years after the operation were 93.3%, 92.8%, 91.5%, 90.3%, 88.5%, 85.7%, and 83.3%, respectively. Multivariate analyses revealed that Helicobacter pylori infection and disease duration > 1 year had a significant effect on the curative rate. No serious complications occurred after RFA in all 198 patients. RFA was safe and effective for gastric LGIN during long-term follow-up.

- Citation: Wang NJ, Chai NL, Tang XW, Li LS, Zhang WG, Linghu EQ. Clinical efficacy and prognostic risk factors of endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for gastric low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2022; 14(3): 724-733

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v14/i3/724.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v14.i3.724

Gastric cancer is a commonly occurring cancer, with morbidity and mortality ranking second among all malignant tumors[1]. In 2000, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the concept of intraepithelial neoplasia in the new classification of digestive system tumors[2]. This classification divides gastric mucosal intraepithelial neoplasia into low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (LGIN) and high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (HGIN) according to the degree of cellular and structural atypia. Currently, the consensus has been reached on the treatment of HGIN[3,4]. For LGIN, relevant studies[5,6] have shown that it can still develop into gastric cancer; thus, some guidelines advocate endoscopic therapy for long-term gastric LGIN[7-9].

At present, endoscopic treatment of gastric LGIN mainly includes two methods: resection therapy and damage therapy. Although resection therapy, such as endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), has shown to be effective in treating LGIN, the operation is difficult, the treatment cost is high, postoperative management is complex, and there is still the possibility of serious complications[10]. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA), as a kind of damage therapy, has been preliminarily reported in some small clinical studies for treatment of gastric LGIN[11-13], which has the advantages of simple operation, lower risk, lower cost and rapid recovery. However, its efficacy and especially the prognostic risk factors are still not fully understood. The aim of this research was to further explore the efficacy and prognostic risk factors of RFA for gastric LGIN in a large clinical sample study.

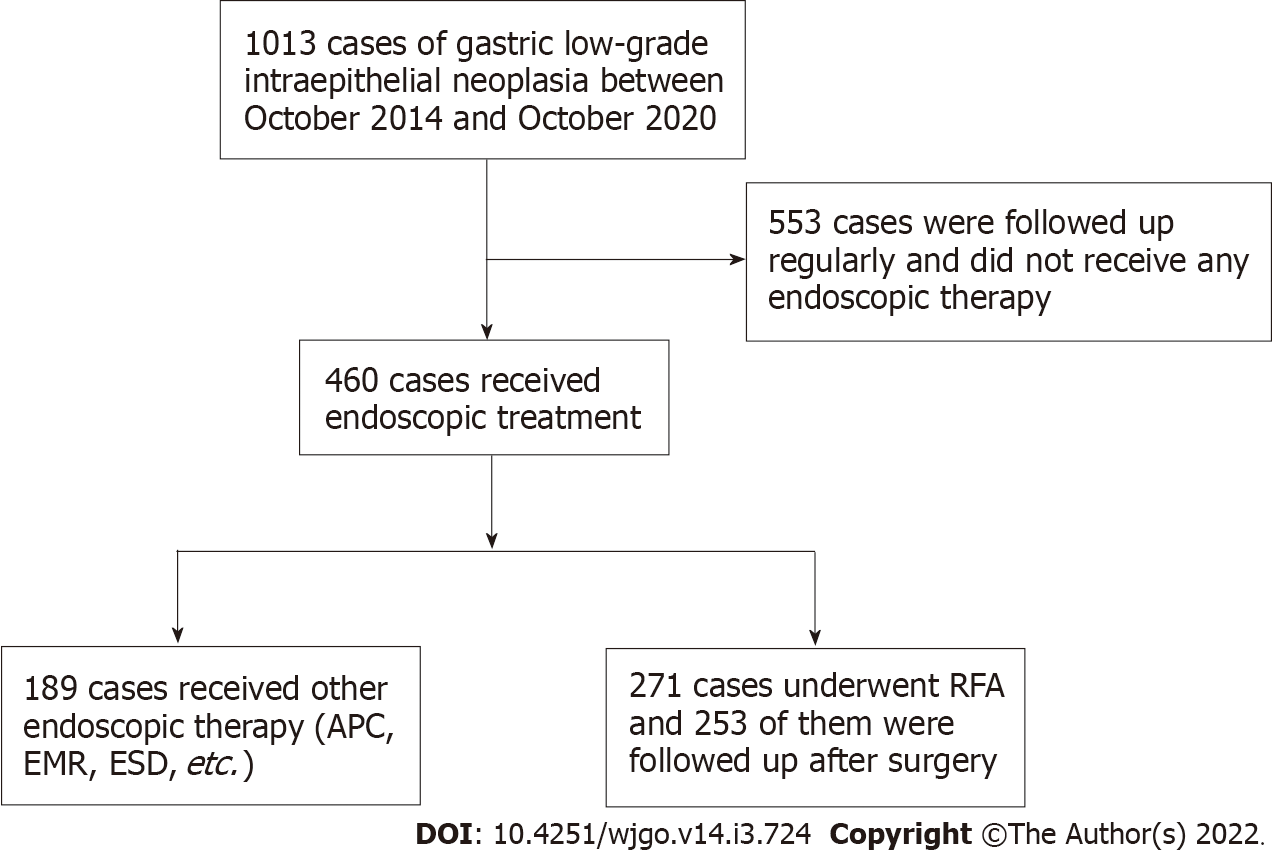

The records of 271 consecutive lesions from 198 patients who received RFA to treat gastric LGIN at the Chinese PLA General Hospital between October 2014 and October 2020 were reviewed for this retrospective study. The detailed flowchart of the study is shown in Figure 1. All the patients provided written informed consent for the procedure. The clinicopathological characteristics and treatment outcomes were retrospectively reviewed using our medical digital engineering database system (Medcare, Qingdao, Shandong Province, China). The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) Macroscopic types of lesion defined as type IIa (superficially elevated), type IIb (flat), and type IIc (superficially depressed), according to the Paris classification[14]; and (2) preoperative biopsy confirmed the lesion as LGIN using the WHO standards before treatment[2]. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients with severe systemic disease or advanced chronic liver disease and a history of gastric surgery; (2) a lesion in which HGIN or early gastric cancer (EGC) was found in the biopsy specimen before treatment; and (3) patients with coagulation dysfunction or those unable to comply with follow-up requirements.

A gastroscope (GIF-Q260J; Olympus Medical, Tokyo, Japan) and the BARRX System (Covidien GI Solutions, Sunnyvale, CA, United States) were used for RFA. A disposable injector (NM-200L-0425; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a normal saline solution was used for submucosal injections. The accessory of the BARRX System (Covidien TTS-1100, 60RFA Conduit 909300) was used for lesion damage. Hemostatic forceps (FD-410 LR; Olympus) and EZ Clip (HX-610-135) were used to prevent hemorrhage and perforation. Other equipment and accessories included a high-frequency generator (ICC-200; ERBE Elektromedizin, Tübingen, Germany) and an argon plasma coagulation unit (APC 300; ERBE) for RFA.

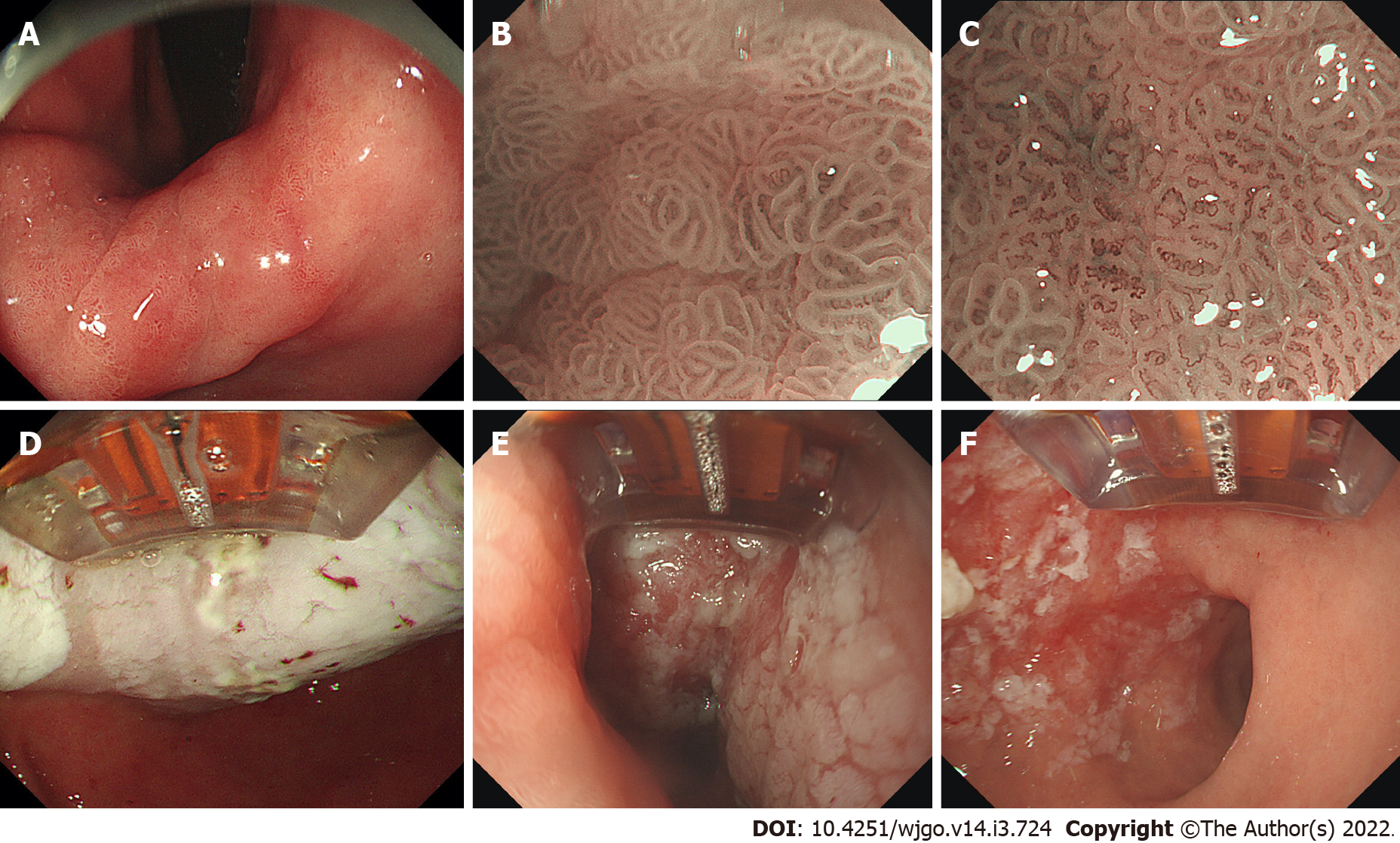

The specific procedures for RFA were as follows. After the lesions were found by routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, the lesions were further observed using magnifying endoscopy (ME) combined with narrow-band imaging (NBI) to determine the size and range. Subsequently, with endoscopic assistance, the RFA electrode was attached to the lesions. We set the power output for RFA as 57 W and the energy density as 15 J/cm2. After ablation, the surface of the lesions showed white coagulation and necrosis. The ablation was repeated three times for each lesion to ensure that the lesion was completely ablated. Before the next ablation, the coagulated necrotic tissue on the surface was removed, which was accomplished with the aid of RFA electrodes. Moreover, there was also a possibility of administering a submucosal injection to the lesion, which is easier to operate. Other details of the RFA procedures were described in our previous study[13].

The RFA procedure, which was performed by three experienced GI endoscopists (Linghu EQ, Chai NL and Wang NJ), is shown in Figure 2. Hemorrhage after ESD was defined as symptomatic bleeding with the need for emergency endoscopy. Perforation was diagnosed by endoscopy or by the presence of free air on abdominal computed tomography. Postoperative abdominal pain was evaluated by Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale[9,15]. Hemorrhage, perforation, and postoperative abdominal pain were the variables recorded and analyzed as complications to evaluate the safety of the procedure. We recommend ME-NBI and targeted biopsies for histological prediction before RFA to treat gastric LGIN. Additionally, along with ME-NBI, it is necessary to combine various endoscopic techniques, including endoscopic ultrasound and chromoendoscopy, in some difficult cases before RFA.

Each patient fasted for 4-6 h after surgery. After that, a liquid or semiliquid diet was administered, followed by gradual transition to a normal diet. At the same time, patients needed oral proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and mucosal protectant for 1 mo after surgery. In addition, we explained the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale to each patient and provided them with a form used for self-recording their daily pain score in the first month after RFA. The form was returned 3 mo after the patient came back to our hospital for the first review.

The curative effect was determined by the pathological results of the biopsy from the original treatment area when patients came back to the hospital for a review after surgery. The specific time of gastroscopy follow-up was 3 mo, 6 mo, and 1-5 years after the operation. The evaluation criteria were: (1) Disappearance of LGIN in the original treatment area indicated by pathological biopsy was considered as curative effect; (2) biopsy of the area of the original treatment that still indicated LGIN was considered as relapse; (3) pathological result of biopsy in the nontherapeutic area indicating LGIN was considered as recurrence; and (4) pathological result of biopsy of the original treatment area indicating HGIN or cancer was considered as disease progression.

We judged the safety of the operation by monitoring the occurrence of complications such as perioperative bleeding and perforation and the time and degree of postoperative abdominal pain in all patients.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Measurement data are expressed as mean value ± SD, whereas numerical data are described by frequency and percentage and were compared by χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. The measurement data were analyzed by t-test and one-way analysis of variance or rank-sum test according to whether the data conformed to a normal distribution. Survival curves were drawn with the Kaplan–Meier method, and intragroup comparisons were made with a log-rank test. Univariate survival analysis was performed with the Cox proportional hazards model, where the variables with P < 0.10 were included in Cox multivariate survival analysis. The hazard ratio and its 95% confidence interval were used to express the relative risk, and the relationship of each variate with the recurrence-free and overall survival of patients was analyzed. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Among all 271 cases that underwent RFA therapy, 253 completed postoperative follow-up. The basic characteristics and endoscopic features of all 253 cases are summarized in Table 1. This study included 167 men, aged 22-84 years (mean 58.51 years), and 86 women, aged 43-78 years (mean 58.23 years). Most of the lesions were located in the antrum of the stomach - pylorus area, while no lesions were ulcerated. All cases underwent RFA in a day ward or outpatient setting and did not require hospitalization.

| Curative | Relapse | Total | P value | |

| Patients, n | 188 (74.3) | 65 (25.7) | 253 | |

| Age, mean ± SD (yr) | 58.51 ± 10.53 | 58.23 ± 8.33 | 58.43 ± 9.99 | 0.83 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.24 | |||

| Male | 128 (68.1) | 39 (60.0) | 167 (66.0) | |

| Female | 60 (31.9) | 26 (40.0) | 86 (34.0) | |

| Location of lesions, n (%) | 0.08 | |||

| Gastric fundus - cardia area | 5 (2.7) | 1 (1.5) | 6 (2.4) | |

| Gastric body | 19 (10.1) | 5 (7.7) | 24 (9.5) | |

| Angle of stomach | 32 (17.0) | 21 (32.3) | 53 (20.9) | |

| Antrum of the stomach - pylorus area | 132 (70.2) | 38 (58.5) | 170 (67.2) | |

| Ulceration | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Helicobacter pylori infection, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 8 (4.3) | 37 (56.9) | 45 (17.8) | |

| No | 180 (95.7) | 28 (43.1) | 208 (82.2) | |

| Atrophy, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 49 (26.1) | 39 (60.0) | 88 (34.8) | |

| No | 139 (73.9) | 26 (40.0) | 165 (65.2) | |

| A course of disease, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| < 1 yr | 138 (73.4) | 14 (21.5) | 152 (60.1) | |

| > 1 yr | 50 (26.6) | 51 (78.5) | 101 (39.9) |

The data of all 253 cases that received RFA and completed follow-up are shown in Table 2. All 253 cases were followed up for 3 mo after surgery, and the curative, relapse, recurrence and progression rates were 93.3%, 6.7%, 7.1% and 0.8%, respectively. During the 6-mo follow-up, there were no cases of progression, and the curative, relapse and recurrence rates were 92.8%, 7.2% and 5.3%, respectively. Similarly, there were also no cases that had progressed at 1-year follow-up, and the curative, relapse and recurrence rates were 91.5%, 8.5% and 9.9%, respectively. The 2-year curative rate of RFA was 90.3%, and the relapse rate, recurrence rate, and progression rate were 9.7%, 8.6%, and 1.1%, respectively. Moreover, 3 years of postoperative follow-up were completed in 61 cases, and the curative, relapse, recurrence and progression rates were 88.5%, 11.5%, 9.8% and 3.3%, respectively. Among all cases, 28 completed the 4-year follow-up, and the curative, relapse and recurrence rates were 85.7%, 14.3% and 14.3%, respectively, with no cases of progression. Only six cases completed the 5-year follow-up, and the curative, relapse and recurrence rates were 83.3%, 16.7% and 16.7%, respectively, and there were also no cases of progression.

| Follow-up period | n | Curative, n (%) | Relapse, n (%) | Recurrence, n (%) | Progression, n (%) |

| 3 mo | 253 | 236 (93.3) | 17 (6.7) | 18 (7.1) | 2 (0.8) |

| 6 mo | 208 | 193 (92.8) | 15 (7.2) | 11 (5.3) | 0 |

| 1 yr | 141 | 129 (91.5) | 12 (8.5) | 14 (9.9) | 0 |

| 2 yr | 93 | 84 (90.3) | 9 (9.7) | 8 (8.6) | 1 (1.1) |

| 3 yr | 61 | 54 (88.5) | 7 (11.5) | 6 (9.8) | 2 (3.3) |

| 4 yr | 28 | 24 (85.7) | 4 (14.3) | 4 (14.3) | 0 |

| 5 yr | 6 | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 0 |

Among the five cases with progression in postoperative follow-up, four were pathologically indicated as HGIN, and one was highly differentiated adenocarcinoma. Three cases with HGIN received additional ESD, while one highly differentiated adenocarcinoma case and one case with HGIN were treated with additional surgery. All of these cases achieved curative resection with no recurrence or local lymph node metastasis during follow-up. In addition, some of the relapse and recurrent cases were treated with RFA again, while others chose to remain under observation. So far, there are still a few cases of LGIN that did not disappear, none of which progressed to HGIN or EGC.

No bleeding, perforation, infection or other serious complications occurred in any of 253 cases. Regarding postoperative abdominal pain, 136 cases showed varying degrees of pain (from grade A to C), with an incidence of 53.8% (136/253). The first day to 12 d after RFA was the main time period for pain occurrence. There were 126 cases with abdominal pain in the curative group and 10 cases in the relapse group, with no significant difference between them (126/236 vs 10/17, P = 0.815).

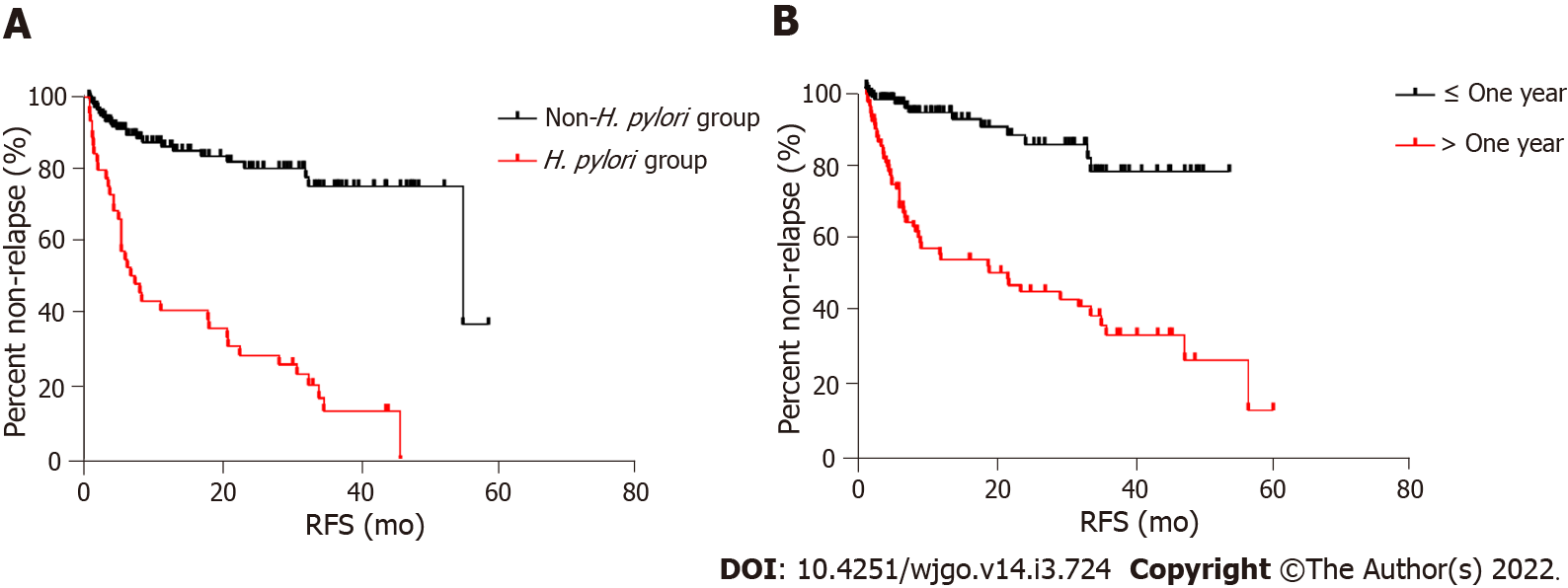

The univariate and multivariate analyses of the outcomes of LGIN after RFA are shown in Table 3. According to results of univariate analysis, sex, age and location of the lesion had no significant effect on the prognosis of LGIN after RFA, with P values of 0.43, 0.89 and 0.29, respectively, while patients with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, atrophic gastritis and disease course > 1 year were more likely to relapse after the procedure (P < 0.001). Subsequently, we included three variables, H. pylori infection, atrophic gastritis, and disease course > 1 year in multivariate analysis, which showed that the two factors of H. pylori infection and disease course > 1 year might be the main risk factors leading to relapse of LGIN after RFA (P < 0.001 and P = 0.013, respectively) (Figure 3).

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | |

| Sex | 0.43 | 0.817 (0.494-1.351) | ||

| Age | 0.89 | 0.998 (0.974-1.023) | ||

| Location | 0.29 | |||

| Gastric body | 0.674 (0.092-4.919) | |||

| Angle of stomach | 1.242 (0.487-3.167) | |||

| Antrum of the stomach - pylorus area | 1.644 (0.963-2.808) | |||

| H. pylori infection | < 0.001 | 6.053 (3.679-9.957) | < 0.001 | 2.662 (1.225-5.788) |

| Atrophy | < 0.001 | 2.136 (1.024-4.453) | 0.597 | 1.170 (0.653-2.097) |

| Course of disease | < 0.001 | 5.482 (3.029-9.919) | 0.013 | 2.662 (1.225-5.788) |

The working principle of RFA is to cause the movement of charged particles in tissues to generate heat through the action of high-frequency alternating current, so as to make the water inside and outside cells evaporate, dry, shrink and fall off, resulting in aseptic necrosis. The power output and energy density of each RFA is rated and does not increase with the duration of operation. RFA is easy to perform and can be completed if the endoscopic physician has the ability to operate the gastroscope. At the same time, there is no bleeding, perforation, infection or other serious complications after RFA. All the above advantages show that RFA has good clinical development prospects.

In our study, the curative rates of endoscopic RFA for gastric LGIN at 3 and 6 mo, and 1-5 years after the operation were 93.3%, 92.8%, 91.5%, 90.3%, 88.5%, 85.7% and 83.3%, respectively. Both the short-term and long-term efficacy were satisfactory. However, these results showed that gastric LGIN still relapsed in some cases after RFA. Therefore, we included multiple variables for univariate and multivariate analyses to try to find risk factors affecting prognosis. The results of the multivariate analysis suggested that H. pylori infection and disease duration > 1 year may be the risk factors for disease relapse, while age, sex, and location of the lesion were not related to disease relapse. Univariate analysis indicated atrophic gastritis as one of the possible risk factors for relapse after RFA; however, the results of multivariate analysis were not fully consistent; thus, the accuracy of this conclusion needs to be further investigated. Alternatively, the longer course of the disease and infection of H. pylori may change the overall state and microenvironment of the gastric mucosa to some extent, which may be one of the possible reasons for the recurrence of LGIN. This is similar to the results of some previous studies[16,17], because the presence of H. pylori makes the mucosa more prone to intestinal metaplasia, and the probability of intraepithelial neoplasia in atrophic and intestinal metaplasia is higher than that in normal mucosa. At the same time, we noted that about two thirds of the lesions were concentrated in the gastric antrum, which may be related to the early occurrence of mucosal atrophy in the gastric antrum and its susceptibility to H. pylori. This also supports our conclusions.

As for the risk factors of LGIN progressing to HGIN or EGC, some studies have reported that it may be related to lesion size > 1 cm, various changes of the lesion surface such as erythema, nodules, erosion and ulceration, and obvious depression of the lesion[18,19]. By reviewing five cases that progressed to HGIN or EGC in the present study, we found that they were all > 1 cm in size. Moreover, four of them showed erythematous nodular changes on the surface, while the other case showed obvious erosion on the surface. All these factors were reflected in the aforementioned studies. We have added ESD or surgical procedures for all five of these cases, which achieved short-term cure, and the long-term prognosis is still being followed up.

Our diagnosis of LGIN was mainly based on preoperative endoscopic biopsy pathology. However, the pathological diagnosis based on endoscopic biopsy is not completely consistent with the real nature of the lesion[20]. Some small and early cancers may exist in the deep mucosa, which exceeds a depth of 200 μm, that can be seen by ME, resulting in diagnostic deviation. However, after RFA treatment, these cancers in the deep mucosa are more likely to be detected by re-examination. The above two reasons may have some influence on the efficacy of RFA for gastric LGIN. Therefore, prospective studies based on a unified pathological definition pathology are needed to verify the reported findings[21].

In terms of complications, more than half of the cases had abdominal pain (136/253) after RFA. The grade of pain was mainly graded as A or B (123/136), with a few grade C (13/136). The pain was tolerated by all patients and gradually relieved with oral PPI and mucosal protectant. Based on the principle of RFA, we considered that such postoperative pain was associated with the local mucosal injury caused by RFA. A small comparative study has shown that submucosal injection can have a protective role in the treatment of mucosal damage and effectively relieve postoperative pain[22], which needs to be confirmed in subsequent large comparative studies.

In this study, we only included LGIN lesions that were macroscopic type 0-II as type 0-I and 0-III were at risk of progressing to HGIN or EGC. Flat lesions were also more conducive to the effective adhesion of the RFA electrode so as to fully achieve the therapeutic effect. Therefore, after taking the above factors into consideration, we chose such inclusion criteria.

During RFA, the electrode should be closely attached to the mucosal surface so that the energy can be fully transmitted. Before the next ablation, the necrotic mucosal tissue on the lesion surface after the previous ablation should be fully removed to avoid reduction of energy conduction, so as to ensure the ablation effect[13]. The above steps can be completed by rotating the endoscope, inhalation, and aeration.

RFA has the following advantages. First, in addition to the satisfactory efficacy and safety demonstrated in our study, the procedure is simple and easy to learn, generally taking 10-20 min to complete. Second, RFA has low cost, which can reduce the economic burden of patients. Third, patients can eat on the day after surgery, without the need for prophylactic antibiotics, which is conducive to recovery. Last but not least, RFA can be performed on an outpatient basis without requiring hospitalization, which is important for saving medical resources. Therefore, based on the above advantages, the future clinical application and popularization of RFA is worth exploring.

The present study had several limitations. First, it was a single-center retrospective study, and future multicenter comparative and randomized trials are needed to confirm our findings. Second, the number of patients with follow-up > 3 years was small, which may affect our prediction of the long-term prognosis of LGIN after RFA. Finally, more cases are needed to evaluate the difference in pain grades between the submucosal and the nonsubmucosal injection groups. Also, future prospective studies based on a unified pathological definition are warranted.

RFA is a safe and effective treatment strategy for gastric LGIN, which is worthy of clinical application and promotion. H. pylori infection and disease course > 1 year may be the main risk factors leading to relapse of LGIN after RFA. For relapsing and recurrent cases, secondary RFA therapy may be considered.

The efficacy and prognostic risk factors of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for gastric low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (LGIN) have not been well analyzed.

We look forward to promoting the use of RFA ablation for gastric LGIN in the future.

To explore the efficacy and prognostic risk factors of RFA for gastric LGIN.

The large sample clinical data of RFA for gastric LGIN were reviewed in this retrospective study. Data on operative parameters, complications, and follow-up outcomes including curative rates were recorded and analyzed.

The near- and long-term efficiency of RFA is satisfactory. Multivariate analyses revealed that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and disease duration > 1 year had a significant effect on the curative rate. None of patients had bleeding, perforation, infection, or other serious complications after RFA, and the main discomfort was postoperative abdominal pain.

RFA is a safe and effective treatment strategy for gastric LGIN, which is worthy of clinical application and promotion. H. pylori infection and disease course > 1 year may be the main risk factors leading to relapse of LGIN after RFA.

We look forward to conducting a multicenter prospective controlled study in the future to further confirm the efficacy of RFA in the treatment of gastric LGIN.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kim E, United States; Snyder M, United States S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359-E386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20108] [Cited by in RCA: 20516] [Article Influence: 2051.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (20)] |

| 2. | Watterson JD, Mahoney JE, Futter NG, Gaffield J. Iatrogenic ureteric injuries: approaches to etiology and management. Can J Surg. 1998;41:379-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Nimura S, Yahagi N, Iishi H, Oka M, Ajioka Y, Ichinose M, Matsui T. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 407] [Article Influence: 45.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Expert group of Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission major project "Study on the treatment standard of early gastric cancer". Expert consensus on endoscopic standardized resection of early gastric cancer (2018, Beijing). Zhonghua Xiaohua Neijing Zazhi. 2019;36:381-392. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Hasuike N, Ono H, Boku N, Mizusawa J, Takizawa K, Fukuda H, Oda I, Doyama H, Kaneko K, Hori S, Iishi H, Kurokawa Y, Muto M; Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Group of Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG-GIESG). A non-randomized confirmatory trial of an expanded indication for endoscopic submucosal dissection for intestinal-type gastric cancer (cT1a): the Japan Clinical Oncology Group study (JCOG0607). Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:114-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wu B, Linghu E, Yang J. The clinical pathology and prognosis of gastric mucosal low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. Jiefangjun Yixueyuan Xuebao. 2011;32:598-600. |

| 7. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Evans JA, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Early DS, Fisher DA, Foley K, Hwang JH, Jue TL, Lightdale JR, Pasha SF, Sharaf R, Shergill AK, Cash BD, DeWitt JM. The role of endoscopy in the management of premalignant and malignant conditions of the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Goddard AF, Badreldin R, Pritchard DM, Walker MM, Warren B; British Society of Gastroenterology. The management of gastric polyps. Gut. 2010;59:1270-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Division of Digestive Endoscopy of Beijing Medical Association. Expert consensus on standardized diagnosis and treatment of gastric low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (2019, Beijing). Zhonghua Weichang Neijing Dianzi Zazhi. 2019;6:49-56. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Kim SY, Sung JK, Moon HS, Kim KS, Jung IS, Yoon BY, Kim BH, Ko KH, Jeong HY. Is endoscopic mucosal resection a sufficient treatment for low-grade gastric epithelial dysplasia? Gut Liver. 2012;6:446-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Baldaque-Silva F, Cardoso H, Lopes J, Carneiro F, Macedo G. Radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of gastric dysplasia: a pilot experience in three patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:863-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Leung WK, Tong DK, Leung SY, Chan FS, Tong TS, Ho RS, Chu KM, Law SY. Treatment of Gastric Metaplasia or Dysplasia by Endoscopic Radiofrequency Ablation: A Pilot Study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2015;62:748-751. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Linghu E, Feng J, Ma X. Clinical study of endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for treatment of low-grade gastroesophageal intraepithelial neoplasia. Zhonghua Weichang Neijing Dianzi Zazhi. 2015;2:14-17. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1117] [Cited by in RCA: 1327] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 15. | Lawson SL, Hogg MM, Moore CG, Anderson WE, Osipoff PS, Runyon MS, Reynolds SL. Pediatric Pain Assessment in the Emergency Department: Patient and Caregiver Agreement Using the Wong-Baker FACES and the Faces Pain Scale-Revised. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37: e950-e954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sung JK. Diagnosis and management of gastric dysplasia. Korean J Intern Med. 2016;31:201-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Liu Y, Cai Y, Chen S, Gou Y, Wang Q, Zhang M, Wang Y, Hong H, Zhang K. Analysis of Risk Factors of Gastric Low-Grade Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Asymptomatic Subjects Undergoing Physical Examination. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:7907195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kim JW, Jang JY. Optimal management of biopsy-proven low-grade gastric dysplasia. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:396-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kang DH, Choi CW, Kim HW, Park SB, Kim SJ, Nam HS, Ryu DG. Predictors of upstage diagnosis after endoscopic resection of gastric low-grade dysplasia. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:2732-2738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lim H, Jung HY, Park YS, Na HK, Ahn JY, Choi JY, Lee JH, Kim MY, Choi KS, Kim DH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Kim JH. Discrepancy between endoscopic forceps biopsy and endoscopic resection in gastric epithelial neoplasia. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1256-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kato M. Diagnosis and therapies for gastric non-invasive neoplasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12513-12518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Niu XT. The protective effects of submucosal injection for gastric low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia treatment. Nankai Daxue. 2016;1-50. |