Published online Feb 15, 2022. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v14.i2.369

Peer-review started: July 12, 2021

First decision: October 3, 2021

Revised: October 4, 2021

Accepted: January 25, 2022

Article in press: January 25, 2022

Published online: February 15, 2022

Processing time: 213 Days and 11.2 Hours

High grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia due to human papilloma viral (HPV) infections is a precursor lesion for squamous cell carcinoma especially in high risk populations. Frequent examination and anal biopsies remain unpopular with patients; moreover they are also risk factors for chronic pain, scarring and sphincter injury. There is lack of uniform, surveillance methods and guidelines for anal HPV specifically the intervals between exam and biopsies. The aim of this editorial is to discuss the intervals for surveillance exam and biopsy, based on specific HPV related biomarkers? Currently there are no published randomized controlled trials documenting the effectiveness of anal screening and surveillance programs to reduce the incidence, morbidity and mortality of anal cancers. In contrast, the currently approved screening and surveillance methods available for HPV related cervical cancer includes cytology, HPV DNA test, P16 or combined P16/Ki-67 index and HPV E/6 and E/7 mRNA test. There are very few studies performed to determine the efficacy of these tests in HPV related anal pre-cancerous lesions. The relevance of these biomarkers is discussed in this editorial. Longitudinal prospective research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of these molecular biomarkers that include high risk HPV serotyping, P16 immuno-histiochemistry and E6/E7 mRNA profiling on biopsies to elucidate and establish surveillance guidelines.

Core Tip: Human papilloma viral (HPV) infections are the most common sexually transmitted infection worldwide and are causally associated with 5%-10% of all cancers. High grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia (anal intraepithelial neoplasia-3, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, carcinoma in situ) is a precursor for anal carcinoma. There is inconsistency and unpredictability of anal dysplasia and its progression to squamous cell cancer. There is an urgent need to identify and validate objective HPV biomarkers for better risk stratification for anal cancers. Extrapolating the data from cervical cancers, prospective longitudinal studies are needed incor

- Citation: Shenoy S. Anal human papilloma viral infection and squamous cell carcinoma: Need objective biomarkers for risk assessment and surveillance guidelines. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2022; 14(2): 369-374

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v14/i2/369.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v14.i2.369

Human papilloma virus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection worldwide and are causally associated with 5%-10% of all cancers[1]. The majority of HPV are benign warts. High grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia [anal intraepithelial neoplasia-3, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), carcinoma in situ] is a precursor for anal carcinoma. There are certain high risk 16, 18, 31 HPV subtypes which are implicated in the etiology for cervical, anal, vulvar, vaginal, penile and oropharyngeal cancers[2].

Unlike cervical cancers, anal malignancies are relatively uncommon in general population, except in well-established high risk subgroups. These include human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive patients (men and women), MSM (men who have sex with men), women with previous HPV related diseases and immunosuppressed (particular post organ and bone marrow transplant) patients[3,4].

Both the incidence and the mortality from squamous cell cancer of anus continue to increase in this high risk population[5]. However, the surveillance protocols are not clearly defined for anal HPV infections.

This may be due to differences in the natural history, tumor biology, treatment modalities and also lack of clear uniform guidelines for screening modalities and surveillance intervals.

This editorial aims to examine the course of recurrent HPV anal disease and progression to anal cancer with the goal of establishing guidelines for surveillance exams. We also discuss newer molecular HPV biomarkers and their role in patho-genesis of anal cancer that may define high risk patient.

Majority of HPV infections are benign warts or low grade anal intra-epithelial neoplasia [low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), anal intra-epithelial lesion (AIN1), and AIN2] and clear spontaneously. Similarly a subset of HSILs may also regress spontaneously[2-4]. Certain host factors such as HIV positivity, smoking, immunosuppression may prevent effective clearance and this may lead to integration of the virus into the host genome[5]. The progression rates of anal HSILs are lower than those of cervical pre-cancer lesions and the pattern of anal HPV disease pro-gression differs between cervical and anal lesion[3,4].

Because squamous cell anal carcinoma occurs commonly in high risk populations and due to the unpredictable nature of anal dysplastic lesions, these patients require frequent monitoring with high resolution anoscopy (HRA) exams and biopsies. Repeated anal examinations and biopsies remain unpopular with the patients and is a high risk factor for noncompliance with risks of losing these patients to follow up, thus spreading the infection. In addition these patients require examination in the operation room which increases the cost and expenditure associated with operating room set up, sedation, anesthesia and fees for biopsies. Further there is risk of surgery and the morbidity associated with repeated anal procedures and may be debilitating. Frequent complications include chronic pain, bleeding, peri-anal scarring with rare severe complications such as anal stenosis or incontinence due to anal sphincter injury and sepsis[6-8]. One way to reduce the HPV burden in the community is to mandate immunization before the onset of sexual intercourse and exposure to HPV. The United States national immunization schedules and recommendation is to offer vaccinations for boys and girls beginning in their teen years and before the onset of sexual activity and also adult men and women with high risk features such as MSM, immunosuppression and those who are previously unvaccinated up to 27 year of age[9]. However these immunization guidelines come with an economic burden are not uniformly followed in other parts of the world.

Progression to invasive carcinoma is associated with persistent high-risk HPV infection with deregulated viral gene expression and leads to excessive cell proliferation, deficient DNA repair, and the accumulation of genetic damage in the infected cell[2,10]. Due to the inconsistency and the unpredictable nature of the anal dysplasia associated with HPV infections, there is a need for better objective biomarkers for close monitoring[2-4]. Scheduling surveillance protocols, only on the basis of HSIL or LSIL on the biopsy specimens may be inadequate and may be subjective assessment. Further there remains a variation amongst different pathologists in reading and assessment of the biopsy specimens.

Currently there are no published randomized controlled trials documenting the effectiveness of anal screening and surveillance programs to reduce the incidence, morbidity and mortality of anal cancers[3,4]. There is lack of uniform guidelines for surveillance on anal HPV specially the frequency for exam and biopsies. In contrast, the currently approved screening and surveillance methods available for HPV related cervical cancer includes cytology, HPV DNA test, P16 or combined P16/Ki-67 index and HPV E/6 and E/7 mRNA test[3]. In contrast there are very few studies performed to determine the efficacy of these tests in HPV related anal pre-cancer and cancers[3,4,11,12]

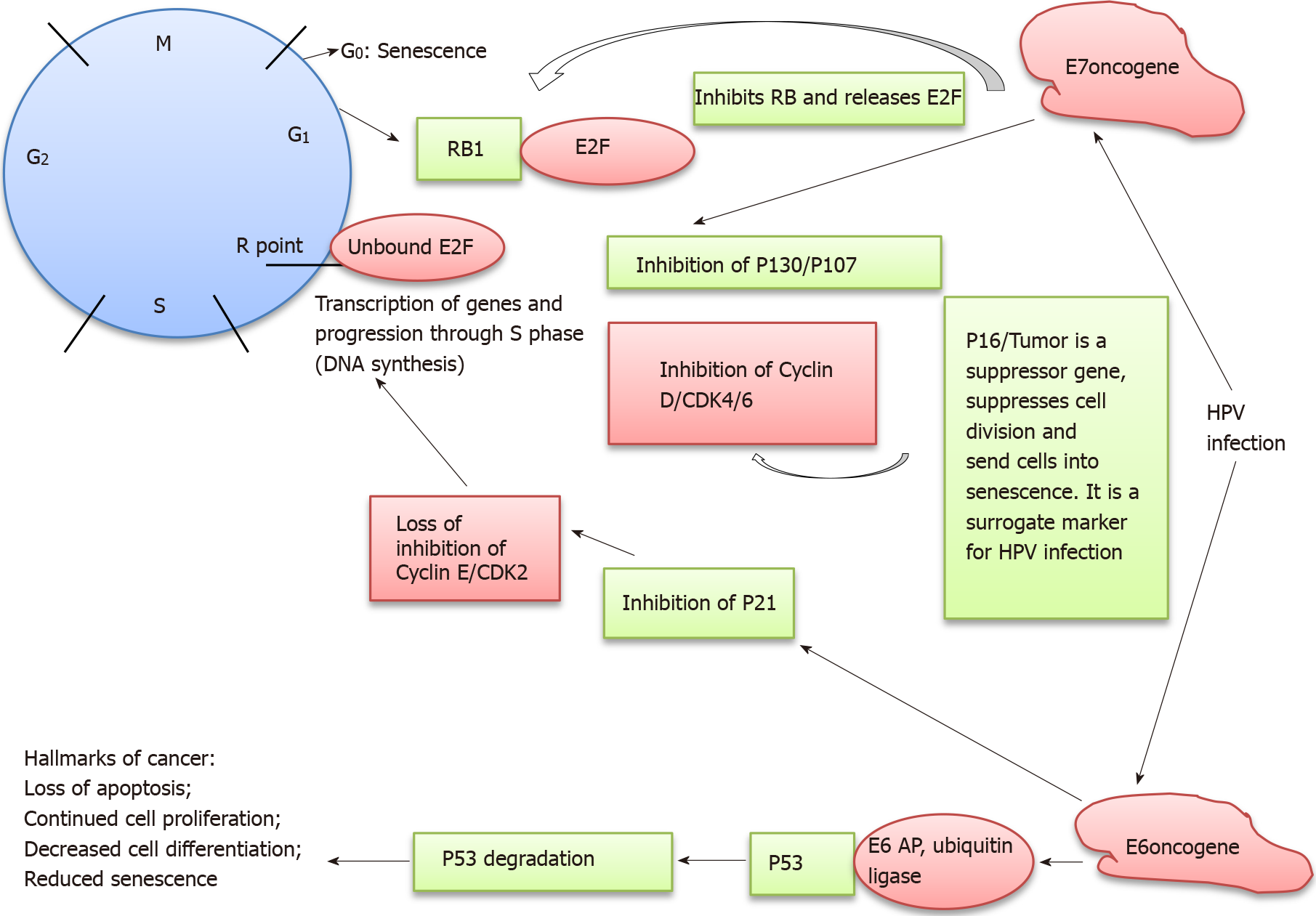

The HPV viral oncogenes (E6, E7) and its targets in the cell cycle needs to be emphasized (Figure 1). This will assist us in identifying useful biomarkers for anal cancer. HPV targets actively proliferating basal cells in the anogenital mucosa and promotes events that are fundamental to neoplastic transformation including early viral oncogene expression and viral persistence[8]. E6 and E7 are two HPV viral oncogenes which up-regulate cellular proliferation, increasing the numbers of infected cells and infectious virions[2]. E6 and E7 viral oncoproteins inactivate a number of the host’s cells tumor suppressor proteins such as P53, P21 and PRb (retinoblastoma) respectively causing dysregulation in G1 to S phase of the cell cycle[10].

P53 is also called the guardian of the genome with mechanisms for DNA repair and in inducing apoptosis. PRb is also referred to as the gatekeeper of the genome. P16 is another tumor suppressor protein which is a marker for increased HPV related cell proliferative state. It inhibits the cyclin D and CDK4/6 proteins. It is also a marker for cell stress and senescence. P16 positivity in HPV infected cells suggests a proliferative state with deregulatory mechanisms in effect. It is thus a surrogate marker for high risk HPV infections[10,13-15].

Suppression of these regulatory proteins keeps the cells in an undifferentiated, dysregulated, proliferative and antiapoptotic state and contributes to malignant transformation[2,13-15]. In addition E6 and E7 oncoproteins also induce epigenetic changes in host genome including histone modification, chromatin modelling and DNA methylation to affect cellular proliferation. Further biological and behavioral factors and inhibition of host immune response also contributes to persistent infection[14-17]

Clinical data from studies for anal HPV, suggests that E6/E7 mRNA has the highest sensitivity and specificity for HSIL detection regardless of HIV status and HPV sub-type 16 and/or18 DNA is useful in predicting progression to HSIL within 12 mo. Phanuphak et al[11] have demonstrated that the combination of these three tests taken together; high-risk HPV DNA, E6/E7 mRNA, and P16 immunocytochemistry identified patients with high risk for progression and need for continuing surveillance HRA and biopsy. Pooled meta-analysis of studies performed by Clarke et al[3] suggested sensitivity and specificity of E6/E7 mRNA to be 74.3% [95% confidence interval (CI): 68.3%-79.6%] and 65.5% (95%CI: 58.5%-71.9%) respectively[3,18,19]. However at present, E6/E7 mRNA evaluation is not used routinely for anal biopsies or approved by appropriate societies.

Increased prevalence of HPV related ano-genital disease in a population leads to low specificity for anal precancerous lesions and cancers. High prevalence correlates with lower specificity for a test. However, narrowing the genotyping to high risk HPV 16/18 subtypes has the potential to improve specificity for anal precancerous lesions (HSIL)[3,11]. Pooled analysis of studies comparing generic HPV genotyping vs specific HPV 16/18 test in detecting anal precancerous (HSIL) improved specificity from 33% (95%CI: 22.2%-46.3%) to 74.3% (95%CI: 67.3%-80.1%) respectively[3].These findings may assist in determining which patients need additional work up and surveillance HRA.

Other markers used for detecting HPV related anogenital precancerous and cancer disease include P16 or P16/Ki-67 index immunostaining[11,12,16,20,21]. A pooled analysis of multiple studies with P16/P16-Ki67 index suggests a sensitivity of 56.6% (95%CI: 27.9%-81.5%) and with specificity of 62.3% (95%CI: 47.8%-74.9%)[3]. Dual P16/Ki-67 staining correlates with higher accuracy than P16 alone for detection of anal pre-cancer and malignant lesions[3].

The progression of recurrent anal HSIL is unpredictable and may require close surveillance with biopsies[3,21,22]. This is particularly true in high risk population as described. Anal HPV lesions can present from the perianal skin and extend proximally through the dentate line and anal transformation zone and up to the distal rectal mucosa[3,23,24]. However frequent anal exams and surgical biopsies have their own risks and limitations. Complications are infrequent but may include chronic pain, bleeding, and peri-anal scarring with resulting anal stenosis or incontinence due to anal sphincter injury and sepsis[8,23]. The therapy of these complications may require further operations and leads to significant morbidity and increased cost.

Other limitations include the anatomy of the anal canal with its corrugated mucosal folds and hemorrhoid tissues that may obscure visualization during anoscopy. Further there is always a concern with patient non-compliance due to distress with repeated invasive exams and biopsies, which remain unpopular.

There is an urgent need to identify and validate objective HPV biomarkers for better risk stratification for anal cancers. Extrapolating the established data from cervical cancers, prospective longitudinal studies are needed incorporating high risk HPV biomarkers and genotyping testing. Taken together there is emerging evidence that E6/E7 mRNA; and P16/Ki67 index testing on anal biopsies may be useful tool in establishing the risk and optimal surveillance intervals. These tests will identify patients at the highest risk for progressive disease.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: KCVA Medical Center, KCVA Medical Center; The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract.

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Romano L S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Lehtinen M, Dillner J. Clinical trials of human papillomavirus vaccines and beyond. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:400-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Doorbar J, Egawa N, Griffin H, Kranjec C, Murakami I. Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease association. Rev Med Virol. 2015;25 Suppl 1:2-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Clarke MA, Wentzensen N. Strategies for screening and early detection of anal cancers: A narrative and systematic review and meta-analysis of cytology, HPV testing, and other biomarkers. Cancer Cytopathol. 2018;126:447-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Palefsky JM. Screening to prevent anal cancer: Current thinking and future directions. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123:509-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Deshmukh AA, Suk R, Shiels MS, Sonawane K, Nyitray AG, Liu Y, Gaisa MM, Palefsky JM, Sigel K. Recent Trends in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anus Incidence and Mortality in the United States, 2001-2015. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112:829-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 52.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yeoh A, Bell S, Farmer C, Carne P, Skinner S, Chin M, Warrier S. Clinical evaluation of anal intraepithelial neoplasia: are we missing the boat? ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:E1-E4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Watson AJ, Smith BB, Whitehead MR, Sykes PH, Frizelle FA. Malignant progression of anal intra-epithelial neoplasia. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:715-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shenoy S, Nittala M, Assaf Y. Anal carcinoma in giant anal condyloma, multidisciplinary approach necessary for optimal outcome: Two case reports and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;11:172-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Petrosky E, Bocchini JA Jr, Hariri S, Chesson H, Curtis CR, Saraiya M, Unger ER, Markowitz LE; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:300-304. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Shenoy S. Cell plasticity in cancer: A complex interplay of genetic, epigenetic mechanisms and tumor micro-environment. Surg Oncol. 2020;34:154-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Phanuphak N, Teeratakulpisarn N, Keelawat S, Pankam T, Barisri J, Triratanachat S, Deesua A, Rodbamrung P, Wongsabut J, Tantbirojn P, Numto S, Ruangvejvorachai P, Phanuphak P, Palefsky JM, Ananworanich J, Kerr SJ. Use of human papillomavirus DNA, E6/E7 mRNA, and p16 immunocytochemistry to detect and predict anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in HIV-positive and HIV-negative men who have sex with men. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wentzensen N, Follansbee S, Borgonovo S, Tokugawa D, Schwartz L, Lorey TS, Sahasrabuddhe VV, Lamere B, Gage JC, Fetterman B, Darragh TM, Castle PE. Human papillomavirus genotyping, human papillomavirus mRNA expression, and p16/Ki-67 cytology to detect anal cancer precursors in HIV-infected MSM. AIDS. 2012;26:2185-2192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Castle PE, Follansbee S, Borgonovo S, Tokugawa D, Schwartz LM, Lorey TS, LaMere B, Gage JC, Fetterman B, Darragh TM, Rodriguez AC, Wentzensen N. A comparison of human papillomavirus genotype-specific DNA and E6/E7 mRNA detection to identify anal precancer among HIV-infected men who have sex with men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:42-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Groves IJ, Coleman N. Pathogenesis of human papillomavirus-associated mucosal disease. J Pathol. 2015;235:527-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vousden KH. Regulation of the cell cycle by viral oncoproteins. Semin Cancer Biol. 1995;6:109-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lin C, Franceschi S, Clifford GM. Human papillomavirus types from infection to cancer in the anus, according to sex and HIV status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:198-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | van der Zee RP, Richel O, van Noesel CJM, Ciocănea-Teodorescu I, van Splunter AP, Ter Braak TJ, Nathan M, Cuming T, Sheaff M, Kreuter A, Meijer CJLM, Quint WGV, de Vries HJC, Prins JM, Steenbergen RDM. Cancer Risk Stratification of Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Positive Men by Validated Methylation Markers Associated With Progression to Cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:2154-2163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jin F, Roberts JM, Grulich AE, Poynten IM, Machalek DA, Cornall A, Phillips S, Ekman D, McDonald RL, Hillman RJ, Templeton DJ, Farnsworth A, Garland SM, Fairley CK, Tabrizi SN; SPANC Research Team. The performance of human papillomavirus biomarkers in predicting anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in gay and bisexual men. AIDS. 2017;31:1303-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sendagorta E, Romero MP, Bernardino JI, Beato MJ, Alvarez-Gallego M, Herranz P. Human papillomavirus mRNA testing for the detection of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in men who have sex with men infected with HIV. J Med Virol. 2015;87:1397-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pandhi D, Bisherwal K, Singal A, Guleria K, Mishra K. p16 immunostaining as a predictor of anal and cervical dysplasia in women attending a sexually transmitted infection clinic. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2016;37:151-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tramujas da Costa E Silva I, Coelho Ribeiro M, Santos Gimenez F, Dutra Ferreira JR, Galvao RS, Vasco Hargreaves PE, Gonçalves Daumas Pinheiro Guimaraes A, de Lima Ferreira LC. Performance of p16INK4a immunocytochemistry as a marker of anal squamous intraepithelial lesions. Cancer Cytopathol. 2011;119:167-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Steele SR, Varma MG, Melton GB, Ross HM, Rafferty JF, Buie WD; Standards Practice Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice parameters for anal squamous neoplasms. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:735-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mistrangelo M, Dal Conte I, Volpatto S, DI Benedetto G, Testa V, Currado F, Morino M. Current treatments for anal condylomata acuminata. Minerva Chir. 2018;73:100-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jay N, Berry JM, Miaskowski C, Cohen M, Holly E, Darragh TM, Palefsky JM. Colposcopic Characteristics and Lugol's Staining Differentiate Anal High-Grade and Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions During High Resolution Anoscopy. Papillomavirus Res. 2015;1:101-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |