Published online Nov 15, 2022. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v14.i11.2253

Peer-review started: July 11, 2022

First decision: August 19, 2022

Revised: September 15, 2022

Accepted: October 2, 2022

Article in press: October 2, 2022

Published online: November 15, 2022

Processing time: 127 Days and 7.5 Hours

This is a unique case of a patient who was found to have two extremely rare primary malignancies synchronously, i.e., an ampullary adenocarcinoma arising from a high-grade dysplastic tubulovillous adenoma of the ampulla of Vater (TVAoA) with a high-grade ileal gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). Based on a literature review and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of this synchronicity. Primary ampullary tumors are extremely rare, with an incidence of four cases per million population, which is approximately 0.0004%. Distal duodenal polyps are uncommon and have a preponderance of occurring around the ampulla of Vater. An adenoma of the ampulla ( AoA) may occur sporadically or with a familial inheritance pattern, as in hereditary genetic polyposis syndrome such as familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome (FAPS). We report a case of a 77-year-old male who was admitted for painless obstructive jaundice with a 40-pound weight loss over a two-month period and who was subsequently diagnosed with two extremely rare primary malignancies, i.e., an adenocarcinoma of the ampulla arising from a high-grade TVAoA and a high-grade ileal GIST found synch

A 77-year-old male was admitted for generalized weakness with an associated weight loss of 40 pounds in the previous two months and was noted to have painless obstructive jaundice. The physical examination was benign except for bilateral scleral and palmar icterus. Lab results were significant for an obstructive pattern on liver enzymes. Serum lipase and carbohydrate antigen-19-9 levels were elevated. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography were consistent with a polypoid mass at the level of the common bile duct (CBD) and the ampulla of Vater with CBD dilatation. The same lesions were visualized with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Histopathology of endoscopic forceps biopsy showed TVAoA. Histopathology of the surgical specimen of the resected ampulla showed an adenocarcinoma arising from the TVAoA. Abdominal and pelvic CT also showed a coexisting heterogeneously enhancing, lobulated mass in the posterior pelvis originating from the ileum. The patient underwent ampullectomy and resection of the mass and ileo-ileal side-to-side anastomosis followed by chemoradiation. Histopathology of the resected mass confirmed it as a high-grade, spindle cell GIST. The patient is currently on imatinib, and a recent follow-up positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed a complete metabolic response.

This case is distinctive because the patient was diagnosed with two synchronous and extremely rare high-grade primary malignancies, i.e., an ampullary adenocarcinoma arising from a high-grade dysplastic TVAoA with a high-grade ileal GIST. An AoA can occur sporadically and in a familial inheritance pattern in the setting of FAPS. We emphasize screening and surveillance colonoscopy when one encounters an AoA in upper endoscopy to check for FAPS. An AoA is a premalignant lesion, particularly in the setting of FAPS that carries a high risk of metamorphism to an ampullary adenocarcinoma. Final diagnosis should be based on a histopathologic study of the surgically resected ampullary specimen and not on endoscopic forceps biopsy. The diagnosis of AoA is usually incidental on upper endoscopy. However, patients can present with constitutional symptoms such as significant weight loss and obstructive symptoms such as painless jaundice, both of which occurred in our patient. Patient underwent ampullectomy with clear margins and ileal GIST resection. Patient is currently on imatinib adjuvant therapy and showed complete metabolic response on follow up PET scan.

Core Tip: This case is distinctive because the patient was diagnosed with two synchronous and extremely rare high-grade primary malignancies, i.e., an ampullary adenocarcinoma arising from a high-grade dysplastic tubulovillous adenoma of the ampulla of Vater (TVAoA) with a high-grade ileal gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). Based on a literature review, this is the first report of an ampullary adenocarcinoma coexisting with an ileal GIST. AoA may occur sporadically or in a familial inheritance pattern, as in the setting of familial adeno

- Citation: Matli VVK, Zibari GB, Wellman G, Ramadas P, Pandit S, Morris J. A rare synchrony of adenocarcinoma of the ampulla with an ileal gastrointestinal stromal tumor: A case report. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2022; 14(11): 2253-2265

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v14/i11/2253.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v14.i11.2253

Solitary adenomas involving the ampulla of Vater (AoV) account for 5% of gastrointestinal tumors, and most are found incidentally on endoscopy[1]. Adenomas of the ampulla of Vater (AoAs) may be sporadic, as in our case, or follow a familial inheritance pattern, as in the setting of familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome (FAPS). Although these lesions are rare, the study of AoA is essential, as they are premalignant, and the risk of progression to an adenocarcinoma is high[1].

We report the case of a 77-year-old male who presented with generalized weakness along with associated decreased appetite and a 40-pound weight loss for approximately two months and who was found to have a solitary high-grade tubulovillous adenoma of the ampulla of Vater (TVAoA); the initial diagnosis was a high-grade TVAoA. However, the diagnosis ultimately changed to an ampullary adenocarcinoma arising from a TVAoA. The patient also had a coexisting small bowel gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). This case is unique because of the synchronicity of two extremely primary malignancies, i.e., an ampullary adenocarcinoma arising from a high-grade dysplastic TVAoA with a high-grade ileal GIST. There is a scarcity of literature on this topic, and we feel it is interesting to discuss the diagnosis, management, and follow-up associated with this case.

The patient was a 77-year-old Caucasian male who presented with generalized weakness and decreased appetite associated with a weight loss of approximately 40 pounds in the last 2 months.

This patient had a medical history significant for essential hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia, and he presented with generalized weakness with decreased appetite associated with a weight loss of approximately 40 pounds in the prior 2 mo. He denied any abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea but noted that recently his urine had become dark and his skin had become yellowish in color.

The patient had a medical history significant for essential hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.

He denied smoking tobacco, alcohol use, or any kind of illicit drug abuse. Family history was insignificant.

The patient’s vital signs were stable. The physical examination was significant for scleral and palmar icterus. No lymph nodes were palpable. The rest of the physical examination findings were benign.

Complete blood counts were normal. A comprehensive metabolic panel revealed a serum sodium level of 128 mmol/L, creatinine level of 1.5 mg/dL, and lipase level of 1904 U/L, which decreased to 755 U/L on the day of discharge. The hepatitis panel was negative. Liver function tests are shown in Table 1, and tumor markers are shown in Table 2.

| Liver function tests | On admission | On discharge |

| ALT | 299 | 196 |

| AST | 122 | 75 |

| ALP | 848 | 754 |

| Total Bilirubin | 5.9 | 2.6 |

| Direct Bilirubin | 4.2 | 2.0 |

| Albumin | 3.0 | 2.6 |

| Tumor marker | Result | Normal range |

| CEA | 0.99 | 0.01-4.00 |

| CA-19 | 454 | 0.00-37 |

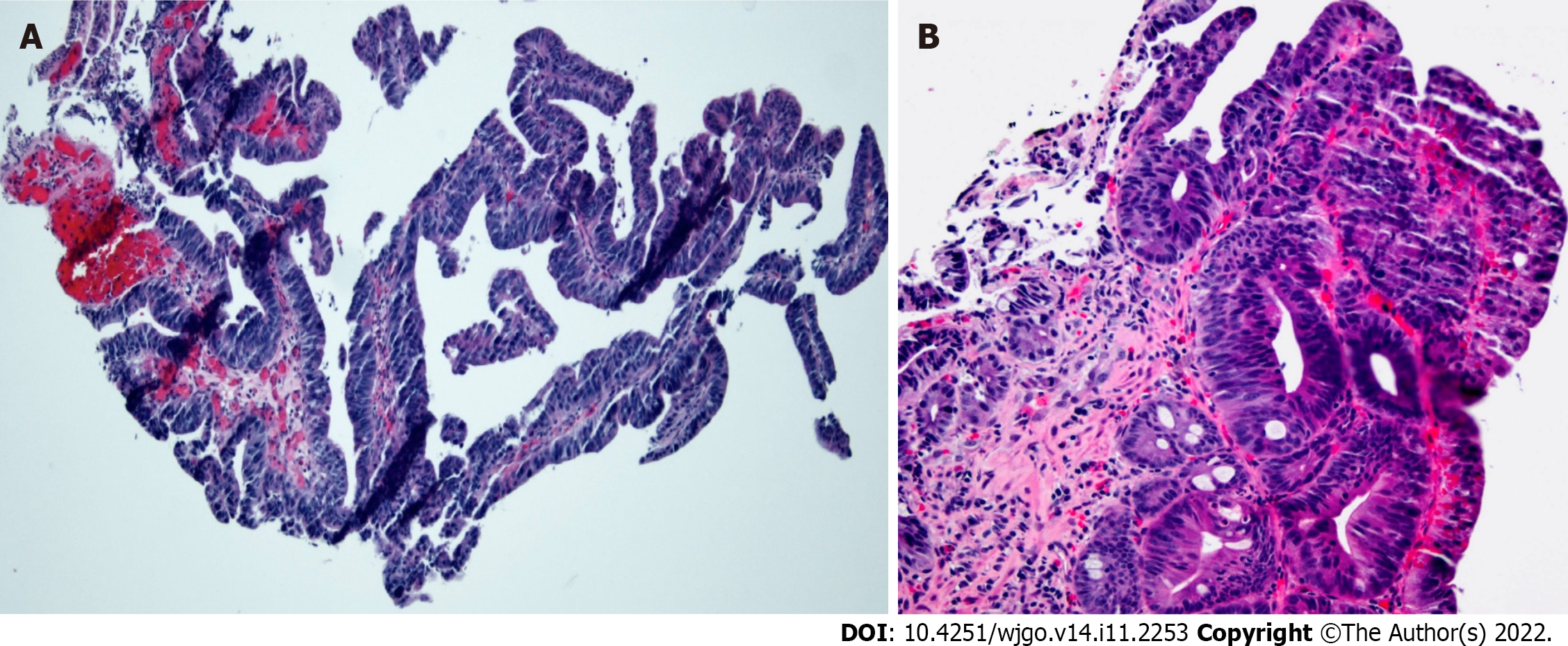

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showed a polypoid, soft tissue mass at the level of the distal common bile duct (DCBD)/AoV measuring approximately 9 mm with resultant intra- and extrahepatic biliary dilatation (Figure 1A and B). The CBD measured 15 mm in diameter, and cystic lesions measuring up to 1 cm were noted in the tail of the pancreas. There was a heterogeneously enhanced lobulated mass with punctate calcifications in the posterior pelvis likely originating from the serosal surface of the pelvic small bowel (Figure 1C and D). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) (Figure 2) showed a polypoid mass again noted at the level of the DCBD/AoV. It measured approximately 2.3 cm × 2.0 cm × 1.7 cm with a slightly prominent pancreatic duct measuring 6 mm in diameter. Given his CT and MRCP findings, medical gastroenterology and general surgery experts were consulted. He underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which showed abnormal papillae with polypoid masses (Figure 3). Sphincterotomy and deep cannulation procedures were performed and confirmed by fluoroscopy. It showed CBD dilatation, and there was an abrupt cutoff at the distal aspect. The general surgery consultant recommended biopsy of the pelvic mass for probable metastatic disease. The patient underwent positron emission tomography (PET), which showed an endo-biliary stent in the region of the papilla, a 1.7 cm ampullary mass with intense fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avidity (Figure 4A) and an oval-shaped, well-defined FDG-avid lesion measuring approximately 6 cm × 3 cm (Figure 4B), with a small punctate area of calcification present within the lesion located deep in the pelvis along the posterior margin of the small bowel loops. No FDG-avid lymph nodes were identified. No lytic or blastic FDG lesions were observed. Histopathology of the ampullary mass that was biopsied on endoscopy showed a tubulovillous adenoma with high-grade dysplasia (Figure 5).

Gazi B. Zibari, MD, FACS, Academic Chairman of the Dept of Surgery, Program Director of Surgery Residency, Director, John C. McDonald Regional Transplant & Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Center, Willis Knighton Health System.

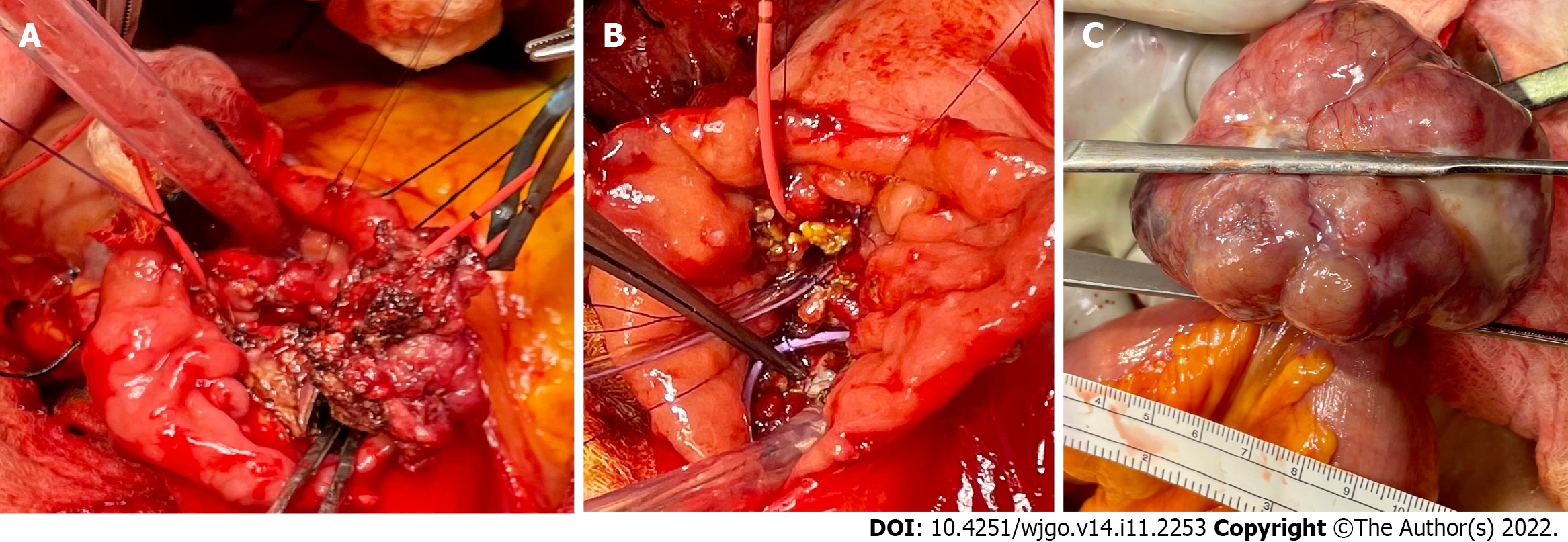

This case was discussed at the hepatobiliary multidisciplinary conference, and all images and paths were discussed. It was recommended for the patient to undergo resection of both the ampullary mass and small bowel lesions. The patient was an ideal candidate for the Whipple procedure, even robotically/laparoscopically. However, the patient only consented to ampullectomy, not to the Whipple procedure. The patient underwent duodenal exploration and was found to have a broad ampullary polypoid lesion that was not amenable to endoscopic resection. However, endoscopic ultrasound and intraoperative ultrasound did not reveal any evidence of pancreatic invasion. We advanced a Fogarty catheter via the cystic duct through the ampulla down to the duodenum. The ampullary mass was excised with a negative margin as well as negative peri-pancreatic/peri-duodenal nodes per frozen section (Figure 6A and B).

Subsequently, a pedunculated ileal GIST was found approximately 150 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve. This was resected en bloc with a loop of small bowel. There was no associated mesenteric adenopathy. Subsequently, side-to-side small bowel anastomoses were created (Figure 6C).

With an adenocarcinoma in the specimen and a close margin on permanent section, the patient did not undergo the Whipple procedure, and the patient also wished to undergo chemotherapy and was therefore scheduled to see medical and radiation oncology experts.

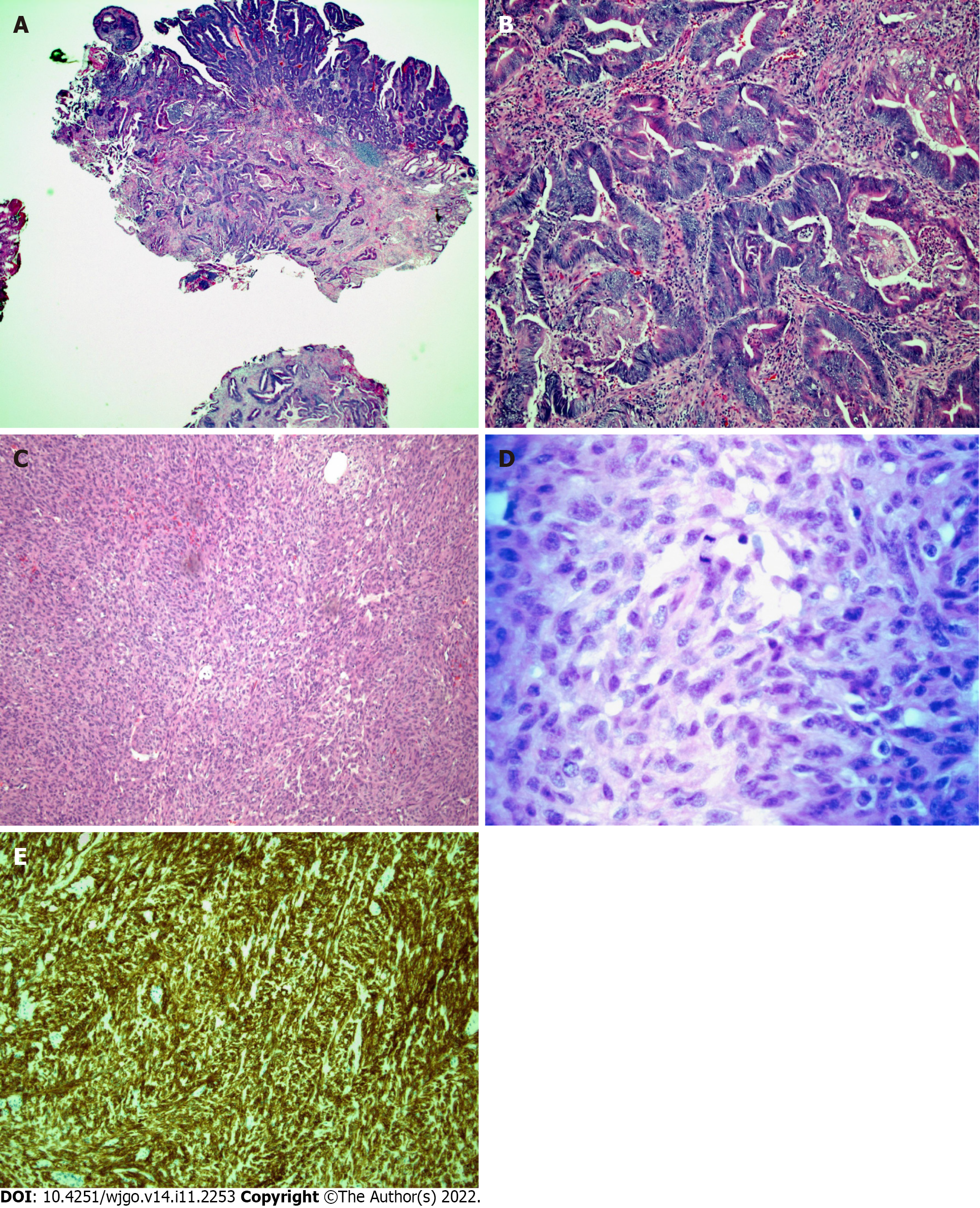

Histopathology of the sections of the ampullary mass (Figure 7A and B) demonstrated a 1.5 cm invasive adenocarcinoma arising from a high-grade dysplastic TVAoA. The tumor invaded the muscularis propria of the duodenum. The tumor invaded 1 mm of the pancreas but did not invade the pancreatic parenchyma. In the intact specimen, no tumor was present at the surgical margins of the resection. Given the likelihood that nonmarginal tissue may be exposed to thermal artifacts, the margins of resection were deemed to be free of tumors.

Histopathology of the sections of the small bowel mass (Figure 7C and D) demonstrated a high-grade, GIST spindle cell type, with 15 mitoses per 5 square millimeters. A series of special stains (Figure 7E) with working controls was performed. The tumor cells were positive for DOG-1 and CD 117, consistent with a GIST.

The final diagnosis was a T2N0M0 adenocarcinoma of the ampulla arising from a high-grade TVAoA coexisting with a T3N0M0 high-grade ileal GIST.

As mentioned above in the multidisciplinary expert consultation, the patient underwent surgical ampullectomy, ileal GIST resection with ileo-ileal side to side anastomosis. The patient was scheduled for chemoradiation as recommended by medical oncologist.

Surveillance CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis w/contrast on three months after surgery showed no findings for metastatic disease (Figure 8).

After three weeks of recovery from ampullectomy, the patient underwent five and half weeks of external beam radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil. He is currently on an adjuvant therapy of imatinib (400 mg per oral daily) for the GIST. His repeat PET scan performed on August 2022 showed a complete metabolic response (16).

This is a unique case of a patient who was found to have two extremely primary malignancies synchronously, i.e., an ampullary adenocarcinoma arising from a high-grade dysplastic TVAoA with a high-grade ileal GIST. Based on a literature review and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of this synchronicity. Primary ampullary tumors are extremely rare, with an incidence of four cases per million population, which is approximately 0.0004%. Distal duodenal polyps are uncommon and have a preponderance of occurring around the ampulla of Vater. Duodenal polyps are found in 4.6% of patients referred for upper endoscopy[2]. Duodenal polyps occur more frequently in the ampulla than in the distal duodenum. Because of the widespread use of upper endoscopy, the incidence of ampullary tumors has been increasing.

Adenomas are the most common ampullary tumors. AoAs can occur as sporadic in a familial inheritance pattern, such as in the setting of FAPS. Two essential points prompted us to write this case report. Firstly, when an AoA is found on upper endoscopy, patients should be sent for screening and periodic surveillance colonoscopy for FAPS. Secondly, AoAs are premalignant lesions can progress to an ampullary adenocarcinoma, which should be identified early for appropriate management and improved outcome. An AoA in the setting of FAPS has a high risk for progression to an ampullary adenocarcinoma. Compared with non-FAPS patients, these patients have an approximately 124-fold increased risk of progression[3]. The diagnosis of an AoA is usually incidental. However, some patients present with obstructive symptoms, such as painless jaundice associated with weight loss, which occurred in our patient due to CBD obstruction[3]. This results in pancreatitis due to pancreatic duct obstruction[3]. When there are constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, an in-depth work-up is needed to evaluate the potential malignant transformation of an AoA. Endoscopic forceps biopsy is only diagnostic in 64% of cases. Diagnostic accuracy is greater when histopathological studies are performed on surgical specimens. Therefore, a final diagnosis should only be made when surgical pathology is available[3,4].

Ampullary carcinoma is the 2nd most common periampullary regional cancer and metastasizes locally in the abdomen and to the liver. Distant metastasis is less common, but there are case reports describing skeletal and brain metastases[1]. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater is a rare tumor accounting for approximately 0.2% of all gastrointestinal malignancies, with an estimated incidence of < 6 cases per million people per year[1]. AoAs and adenocarcinomas originate from the glandular epithelium of the AoV[5]. The cell of origin of these cancers is the epithelial covering of the distal parts of the CBD, pancreatic duct, and periampullary duodenum. Histological subtypes that are common are mucinous, signet ring cell, neuroendocrine, and undifferentiated carcinomas.

A study by Seifert et al[6] revealed that 30% of ampullary adenomas progressed to ampullary adenocarcinomas, which were found during surgery or on follow-up. It also showed that 41.2% of surgically resected ampullary adenocarcinoma patients had residual well-differentiated adenomatous tissue[6].

The next step after diagnosis is established is staging. The usual imaging modalities are CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, MRCP, endoscopic ultrasound, and endoscopic intraductal ultrasound. If there is any biliary tree abnormality in the CT or MRCP, then ERCP plays an important role. ERCP can be diagnostic for determining the extent of the spread of the tumor followed by sphincterotomy and stent placement to facilitate pancreaticobiliary drainage[3].

Incidental and small adenomas may not need any treatment, but high-grade dysplastic tubulovillous adenomas require definitive treatment due to the potential risk of progression to an adenocarcinoma[5].

Management of an ampullary adenocarcinoma:

The patient had a broad-based adenoma in the ampulla, and ampullectomy could have been performed robotically, but it would have been performed for a longer time, and we were concerned about negative margins. On the other hand, a robotic Whipple procedure is possible, but the patient did not agree to that procedure.

In regards to the ileal GIST, minimally invasive surgical resection and robotic resection are available options, although rupture of the tumor may be a potential complication. We have done many of these procedures and have never had a rupture at our facility; in fact, robotic articulation does help to maneuver the tumor without traumatizing it. Therefore, we can perform both ampullectomy, duodenal polyp excision and GIST with minimally invasive surgery either robotically or laparoscopically; some at our facility prefer robotic procedures because of the ease of anastomosis and articulation of the robot. With the Whipple procedure, we can obtain clear margins, but duodenal/ampullary lesions are more challenging because of the risk of positive margins.

An overview of the management of ampullary adenomas and ampullary carcinomas is described in Table 3.

| Endoscopic | Surgical | |||

| Curative | Palliative | Surveillance | Trans-duodenal ampullectomy | Radical or Whipple’s resection |

| Endoscopic snare polypectomy or piecemeal polypectomy | Invasive ampullary adenocarcinoma | FAPS | Benign ampullary adenomas that are difficult to operate on endoscopically[7]. The advantage of this is less morbidity and mortality and alternative access to ampullary tumor resection[7] | Ampullary adenocarcinoma. Radical resection if tumor burden in the duct is high |

GISTs are rare tumors comprising 3% of gastrointestinal tumors but are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the GI tract[4]. The most common sites are the stomach (60%) and small bowel (30%)[2,3]. These are sporadic tumors, unlike ampullary adenomas. Some studies report that the incidence significantly varies from 0.4 to 2.0 cases per 100000 per year, with a slight male preponderance and a median age of 60-65 years[7-9].

GISTs are malignant mesenchymal tumors whose cell of origin is the myenteric interstitial cells of Cajal; they are also known as pacemaker cells of the GI tract and are found in the proximal muscles surrounding the intermuscular plexus of the GI tract. They are soft tissue sarcomas of the GI tract, but they differ in genetics, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, and management[4].

Most GISTs have universal expression of c-KIT/CD117. DOG-1 is another novel marker and can be seen in c-kit-negative cases. The mitotic rate can predict the risk of recurrence.

In 1998, a breakthrough was achieved when the tyrosine kinase receptor mutation c-kit was identified[10]. The most common mutations in GISTs are located in c-KIT exon 11 in approximately 65% of cases and exon 9 in approximately 10%. GISTs with exon 11 mutations are more sensitive to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib than those with exon 9 mutations.

Platelet-derived growth factor alpha (PDGFRA) mutations account for approximately 5%-10% of cases. Mutations are located on exons 12, 14, and 18. It is important to identify the D842 V2V mutation in exon 18, as this mutation confers resistance to imatinib. Avapritinib is the preferred treatment for GISTs with this mutation[4].

Other rare GIST mutations are BRAF and NTRK gene rearrangements, which carry therapeutic implications. Histopathological diagnosis depends upon morphological and immunochemical analysis of the tumor. Immunochemistry is usually positive for CD117(KIT) and/or DOG-1 in 95% of patients. Five percent of GISTs are negative for CD117 and/or DOG-1[8].

Mutational analysis of GISTs is important, as it has good predictive value for sensitivity to targeted therapy, as noted previously, and prognosis. The European Society for Medical Oncology practice guidelines recommend testing for mutations as a part of the diagnostic workup for all high-risk GISTs. GISTs negative for KIT/PDGFRA require subsequent immunochemical testing for succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit-B.

Management of GISTs includes multidisciplinary consultation with pathologists, radiologists, surgeons, medical oncologists, and gastroenterologists, etc., to achieve better outcomes.

Standard management of a localized GIST is complete surgical resection or excision without dissection of clinically negative lymph nodes. The goal is to excise the tumor with negative margins. Tumors greater than 2 cm in size should be biopsied and surgically resected. If less than 2 cm in size, surveillance via endoscopic ultrasound can be performed. However, if lesions are suspicious, then they should be surgically resected. Small GISTs located in the upper and lower GI tract can be resected endoscopically by a surgeon who has endoscopic expertise.

Systemic therapy is performed as a neoadjuvant or adjuvant based on tumor size and other characteristics and is the main strategy for the management of advanced/metastatic disease (Tables 4 and 5).

| Imatinib-sensitive mutation | Imatinib-insensitive mutation | ||||

| Uncomplicated (No major complications expected with surgery) | Complicated (Major complications expected with surgery) | See Table 5 | |||

| Surgery (Resection of tumor with negative margins) | Preoperative imatinib for 6 mo | ||||

| Low/Intermediaterisk | High risk | Tumor negative or microscopically positive margins feasible | Tumor negative or microscopically positive margins not feasible | ||

| Follow-up | Adjuvant treatment with imatinib for 36 mo | Low/Intermediaterisk | High risk | Manage as advanced GIST or metastatic GIST | |

| Follow-up | Adjuvant imatinib for 36 mo | ||||

| Imatinib-sensitive mutations | Imatinib-insensitive mutations | ||||||

| KIT mutations (except exon-9 variety) | Exon-9 KIT mutations | PDGFRA842 V2V mutation | BRAF mutation | NTRK translocation | SDHB | All other mutations | |

| Imatinib 400 mg daily | Imatinib 800 mg daily | Avapritinib | BRAF inhibitor | NTRK inhibitorentrectiniblarotrectinib | Customized management | Sunitinib | |

| Imatinib responsive | Imatinib unresponsive | ||||||

| Surgery of the residual disease and continue imatinib for life | Excision and ablation of progressing lesion | Add and continue sunitinib if responsive | |||||

The first-line treatment for KIT exon-9-mutated GISTs is imatinib (800 mg daily), whereas avapritinib (300 mg daily) is the first-line treatment for GISTs with PDGFRA exon 18 D842 V2V mutation[8]. The imatinib dose can be escalated from 400 mg to 800 mg when there is disease progression. Second-line therapy with sunitinib (50 mg daily) is recommended when there is intolerance to imatinib or progressive disease. Regorafenib (160 mg daily) is generally the third-line therapy for patients unresponsive to imatinib and sunitinib. Ripretinib (150 mg daily) is approved in patients who have received prior treatment with three or more kinase inhibitors, including imatinib.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend follow-up with history and physical and imaging studies every 3 to 6 mo for the first 5 years and then annually after complete resection of GISTs. Relapse to the liver and peritoneum can occur, but distant metastasis to bone and other sites is rare.

The coexistence of the malignancies described in this case is extremely rare, and to our knowledge, this is the first reported case in the literature. Mazur and Clark[10] first published the term GIST in 1983; initially, we considered GISTs as neoplasms of smooth muscle cells and called them gastrointestinal smooth muscle tumors[10]. There have been case reports in the literature reporting GISTs occurring with other histologically diverse parallel primary malignancies. There have been reported occurrences of GISTs of the gastric antrum with colorectal adenocarcinomas[11] and duodenal GISTs with rectal adenocarcinomas[12]. There has been increasing evidence of coexistent, contemporaneous GISTs with other neoplasms of the breast, digestive tract, liver and urogenital system[7,13,14].

This case is distinctive because the patient was diagnosed with two synchronous and extremely rare high-grade primary malignancies, i.e., an ampullary adenocarcinoma arising from a high-grade dysplastic TVAoA with a high-grade ileal GIST. An AoA can occur sporadically and in a familial inheritance pattern in the setting of FAPS. We emphasize screening and surveillance colonoscopy when one encounters an AoA in upper endoscopy to check for FAPS. An AoA is a premalignant lesion, particularly in the setting of FAPS that carries a high risk of metamorphism to an ampullary adenocarcinoma. Final diagnosis should be based on a histopathologic study of the surgically resected ampullary specimen and not on endoscopic forceps biopsy. The diagnosis of AoA is usually incidental on upper endoscopy. However, patients can present with constitutional symptoms such as significant weight loss and obstructive symptoms such as painless jaundice, both of which occurred in our patient. Patient underwent ampullectomy with clear margins and ileal GIST resection. Patient is currently on imatinib adjuvant therapy and showed complete metabolic response on follow up PET scan.

The authors express their deepest appreciation to Manish Dhawan MD, Department of Hematology and Oncology and Dustin Hadley, Physician assistant, Department of Gastroenterology, Christus Highland Medical Center, who provided insightful comments about this research.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Frosio F, Italy; Li W, China; Pan Y, China S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang XD

| 1. | Voutsadakis IA, Doumas S, Tsapakidis K, Papagianni M, Papandreou CN. Bone and brain metastases from ampullary adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2665-2668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Joensuu H, Hohenberger P, Corless CL. Gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Lancet. 2013;382:973-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in RCA: 483] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kadado KJ, Abernathy OL, Salyers WJ, Kallail KJ. Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor and Ki-67 as a Prognostic Indicator. Cureus. 2022;14:e20868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sugiyama Y, Sasaki M, Kouyama M, Tazaki T, Takahashi S, Nakamitsu A. Current treatment strategies and future perspectives for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2022;13:15-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sun JH, Chao M, Zhang SZ, Zhang GQ, Li B, Wu JJ. Coexistence of small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and villous adenoma in the ampulla of Vater. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4709-4712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Seifert E, Schulte F, Stolte M. Adenoma and carcinoma of the duodenum and papilla of Vater: a clinicopathologic study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:37-42. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Nilsson B, Bümming P, Meis-Kindblom JM, Odén A, Dortok A, Gustavsson B, Sablinska K, Kindblom LG. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era--a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103:821-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 803] [Cited by in RCA: 875] [Article Influence: 43.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Casali PG, Blay JY, Abecassis N, Bajpai J, Bauer S, Biagini R, Bielack S, Bonvalot S, Boukovinas I, Bovee JVMG, Boye K, Brodowicz T, Buonadonna A, De Álava E, Dei Tos AP, Del Muro XG, Dufresne A, Eriksson M, Fedenko A, Ferraresi V, Ferrari A, Frezza AM, Gasperoni S, Gelderblom H, Gouin F, Grignani G, Haas R, Hassan AB, Hindi N, Hohenberger P, Joensuu H, Jones RL, Jungels C, Jutte P, Kasper B, Kawai A, Kopeckova K, Krákorová DA, Le Cesne A, Le Grange F, Legius E, Leithner A, Lopez-Pousa A, Martin-Broto J, Merimsky O, Messiou C, Miah AB, Mir O, Montemurro M, Morosi C, Palmerini E, Pantaleo MA, Piana R, Piperno-Neumann S, Reichardt P, Rutkowski P, Safwat AA, Sangalli C, Sbaraglia M, Scheipl S, Schöffski P, Sleijfer S, Strauss D, Strauss SJ, Hall KS, Trama A, Unk M, van de Sande MAJ, van der Graaf WTA, van Houdt WJ, Frebourg T, Gronchi A, Stacchiotti S; ESMO Guidelines Committee, EURACAN and GENTURIS. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2022;33:20-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 108.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Søreide K, Sandvik OM, Søreide JA, Giljaca V, Jureckova A, Bulusu VR. Global epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST): A systematic review of population-based cohort studies. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;40:39-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 579] [Cited by in RCA: 521] [Article Influence: 57.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Mazur MT, Clark HB. Gastric stromal tumors. Reappraisal of histogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:507-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 581] [Cited by in RCA: 560] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hussein MR, Alqahtani AS, Mohamed AM, Assiri YI, Alqahtani NI, Alqahtani SA, Ali HM, Elyas AAA, Al-Shraim MM, Hussain SS, Abu-Dief EE. A Unique Coexistence of Rectal Adenocarcinoma and Gastric Antral Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor: A Case Report and Minireview. Gastroenterology Res. 2021;14:340-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hakozaki Y, Sameshima S, Tatsuoka T, Okuyama T, Yamagata Y, Noie T, Oya M, Fujii A, Ueda Y, Shimura C, Katagiri K. Rectal carcinoma and multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) of the small intestine in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vassos N, Agaimy A, Hohenberger W, Croner RS. Coexistence of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST) and malignant neoplasms of different origin: prognostic implications. Int J Surg. 2014;12:371-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Waidhauser J, Bornemann A, Trepel M, Märkl B. Frequency, localization, and types of gastrointestinal stromal tumor-associated neoplasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:4261-4277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |