Published online Dec 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i12.561

Peer-review started: September 8, 2017

First decision: September 26, 2017

Revised: October 18, 2017

Accepted: November 15, 2017

Article in press: November 15, 2017

Published online: December 16, 2017

Processing time: 90 Days and 12.3 Hours

To investigate the efficacy of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) at diagnosing and treating superficial neoplastic lesions of the stomach in a United Kingdom Caucasian population.

Data of patients treated with or considered for ESD at a tertiary referral center in the United Kingdom were retrieved for a period of 2 years (May 2015 to June 2017) from the electronic patient records of the hospital. Only Caucasian patients were included. Primary outcomes were curative resection (CR) and were defined as ESD resections with clear horizontal and vertical margin and an absence of lympho-vascular invasion, poor differentiation and submucosal involvement on histological evaluation of the resected specimen. Secondary end-points were reversal of dysplasia at 12 mo endoscopic follow-up and/or at the latest follow up. Change in histological diagnosis pre and post ESD was also analysed.

Twenty-four patients were initially identified with intention to treat. 19 patients were eligible after mapping gastroscopy and ESD was attempted on a total of 25 ESD lesions, 4 of which failed and had to be aborted mid-procedure. Out of 21 ESD performed, en-bloc resection was achieved in 71.4% of cases. Resection was considered complete on endoscopy in 90.5% of cases compared to only 38.1% on histology. A total of 6 resections were considered curative (28%), 5 non-curative (24%) and 10 indefinite for CR or non-CR (24%). ESD changed the histological diagnosis in 66.6% of cases post ESD. Endoscopic follow-up in the “indefinite” group and CR group showed that 50% and 80% of patients were clear of dysplasia at the latest follow-up respectively; 2 cases of recurrence were observed in the “indefinite”group. Survival rate for the entire cohort was 91.7%.

This study provides early evidence for the efficacy of ESD as a therapeutic and diagnostic intervention in Caucasian populations and supports its application in the United Kingdom.

Core tip: Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a minimally invasive technique used to diagnose or treat early neoplastic lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. Imported from Far East countries, where it is extensively used, this intervention has proven to be highly effective in carefully selected patients and to constitute a viable alternative to radical surgery. ESD is relatively new in the West and local evidence to support its use in the United Kingdom lacking. This retrospective study provides early evidence in favour of the use of ESD in the United Kingdom.

- Citation: Sooltangos A, Davenport M, McGrath S, Vickers J, Senapati S, Akhtar K, George R, Ang Y. Gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection as a treatment for early neoplasia and for accurate staging of early cancers in a United Kingdom Caucasian population. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(12): 561-570

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i12/561.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i12.561

Endoscopic resection (ER) is a minimally invasive technique aimed at staging or curing dysplastic lesions and intramucosal cancers of the gastrointestinal tract. ER includes endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), their respective application mainly depending on the size of the tumour[1]. EMR was the first endoscopic treatment proven to be as effective as gastrectomy at managing early gastric cancers, with curative rates as high as 85%[1]. However, in lesions larger than 20mm, ESD is preferred as it can achieve higher rates of en-bloc resections and consequently lower recurrence rates[1-7]. En-bloc resections almost constitute a prerequisite for accurate histological evaluation of the resected specimen.

ER is also considered the only definitive method of excluding invasion in otherwise precancerous lesions, where time and again, endoscopic biopsies and endoluminal ultrasound have proven inadequate[2,8,9]. ER can change the diagnosis in up to 40% of cases, more commonly resulting in an upstaging[10-12]. It provides vital information about the depth of invasion of the tumour and as the latter constitutes the strongest predictor of lymph node metastasis[13,14], it is used to guide subsequent management decisions, in particular the indication for surgery. When compared to surgery, ESD appears to have comparable oncologic outcomes with the advantage of shorter operation times, shorter hospital stays and lower complication rates[15].

Most evidence for the efficacy and safety of ESD comes from Eastern countries, where ESD has been shown to achieve curative resection (CR) rates as high as 97% in lesions that meet the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA) guidelines[16-18]. Despite being a technically challenging procedure and carrying a high risk of adverse events in inexperienced hands[19], ESD is gradually gaining popularity in Western countries, partly facilitated by technological advancements[20]. However, evidence for ESD is still scarce in Western populations. One of the few studies carried out in Germany showed promising results with a high rate of en-bloc resections and remarkably low recurrence rates of 1.5%[21]. In the United Kingdom, the JGCA criteria guidelines are used to select lesions amenable to ESD. However, since the outcomes of ESD are heavily dependent on the level of skills of the endoscopist, more local studies are crucial[22,23]. The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence in the United Kingdom only take into account United Kingdom studies when formulating local clinical guidelines. No studies have considered the efficacy of gastric ESD in a United Kingdom Caucasian population up to this date.

This retrospective study is part of our service development and audit and aims to investigate the efficacy of ESD at treating early neoplastic lesions of the stomach in a Caucasian population at a tertiary referral centre in the United Kingdom and secondly, its application for staging early cancers.

Inclusion criteria: Data was obtained for a period of 2 years from May 2015 to June 2017. Only Caucasian patients with gastric cancers staged at or below T1a N0M0 on the basis of computed tomography (CT) scans (or Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography (PET-CT) in a few cases) and Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) were included in this study.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with gastric cancers staged at T1bN0M0 or above were excluded from the study on the basis of CT scans (or PET-CT scans in a few cases) and EUS .

Mapping oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (mapping OGD, a pre-ESD check to evaluate if the case is suitable for ESD) was used to assess the macroscopic appearance of the lesions, the position and size, the presence of ulceration, any field changes and importantly whether the lesions were liftable. The degree of lift of each lesion was graded according to the Kato classification where Kato 1 denotes lifting without any resistance, Kato 2 lifting with some resistance and Kato 3 no lifting[24]. Endoscopic imaging enhancements used included White Light Imaging, Olympus Narrow Band Imaging (NBI) or Fuji Fluorescent Intelligent Chromoendoscopy, indigo carmine spray and acetic acid spray. Biopsies were taken prior to any intervention to assess or re-assess the type of neoplasia present and the degree of differentiation. Poor differentiation and non-lifting sign (Kato 3) precluded ESD except in one patient whose co-morbidities notably liver cirrhosis Child’s Grade A made him unfit for surgery. Endoscopy reports, histology reports and multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meeting letters were retrieved from the electronic patient record of the hospital. The information about each patient’s demographic data, pre-ESD endoscopic assessment, index procedure, follow-up endoscopy, surgery and outcome at the latest follow up were recorded. Microsoft Excel has been used to record all data and for all statistical analyses.

Olympus Double Channel Double-Headed Scope or Fuji Dual Channel Endoscope were used in all procedures and the procedures were jointly performed by two experienced interventional gastroenterologists. The ESD procedure was carried out in theatre (operating room) with the patient under general anaesthesia. The patient was intubated with the assistance of an anaesthetist and endoscopy performed using carbon dioxide gas only. The ESD equipment used for dissection included Olympus ITknife2 Electrosurgical Knife (KD-611L), Olympus ITknife nano Electrosurgical Knife (KD-612L/U), Fujifilm Flush Knife, Fujifilm Clutch Clutter and ERBE Hybrid O Knife. A soft transparent hood (D-201-13404; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was attached to the tip of the endoscope to obtain good endoscopic views of the submucosal layer. In some cases, additional image enhancing techniques (as outlined above) had to be used. This was done through a 2-channel scope equipped with multibending and water jet functions attached to the tip of the endoscope. The lesions were lifted with EMR solution and marking dots were placed using argon on the normal mucosa at approximately 5 mm from the tumour margin to provide safety margins. EMR solution (consisting of a small amount of indigo carmine and 0.1% lidocaine) was then injected into the submucosal layer and a mucosal incision made outside the marking dots. In case of poor mucosal elevation due to ulceration of the lesion or extensive fibrosis of the submucosal layer, hyaluronic acid solution was added to the injection solution to achieve better lift. After mucosal incision, dissection of the submucosal layer was performed, thus achieving en bloc resection.

Each patient was given oral Omeprazole 40 mg, twice daily for at least 3 mo (or another equivalent proton pump inhibitor) after the procedure.

The resected specimen was cut into 4-mm-thick slices after formalin fixation. The histological type, size, depth of invasion, horizontal and vertical margins (HM and VM respectively), and lympho-vascular invasion were evaluated in each slice according to the JGCA Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma criteria. To reconcile and allow for the efficacy of ESD to be more accurately investigated in Western populations, a more systematic approach to reporting histological findings such as the Vienna classification was also used[25]. The measure of efficacy in this study is CR. A resection is considered curative if it achieves clear vertical and horizontal margins and if histological evaluation of the resected specimen shows neither poor differentiation, nor lympho-vascular invasion nor submucosal involvement[3]. An ESD resection is coded as non-CR if it fails to meet all aforementioned criteria and as “indefinite” if data is inadequate to confirm either CR or non-CR. All resected lesions were coded as “complete resection on endoscopy” unless otherwise specified; a resection was considered to be “complete resection on histology” if the VM and the horizontal margin (HM) were clear on histology. The position of lesion was coded as Upper stomach if it was found in the cardia or fundus, as Mid stomach if in the body and as Lower stomach if in the antrum, pylorus or incisura. The age of the patient was at the time of the index procedure.

The secondary end-point was complete reversal of dysplasia at 12 mo endoscopic follow-up and/or at the latest follow-up and was investigated in the “indefinite” group and the CR group. The schedule for endoscopic surveillance for site check is 3 mo after the procedure and then 6 monthly for first year and then yearly thereafter, for 5 years. This outcome considers a patient as one entity, regardless of the number of ESD resections he/she may have had. The change in histological diagnosis pre and post ESD has also been recorded to assess the ability of ESD to influence diagnosis. The histological diagnosis is recorded as the worst histological grade reported for each lesion.

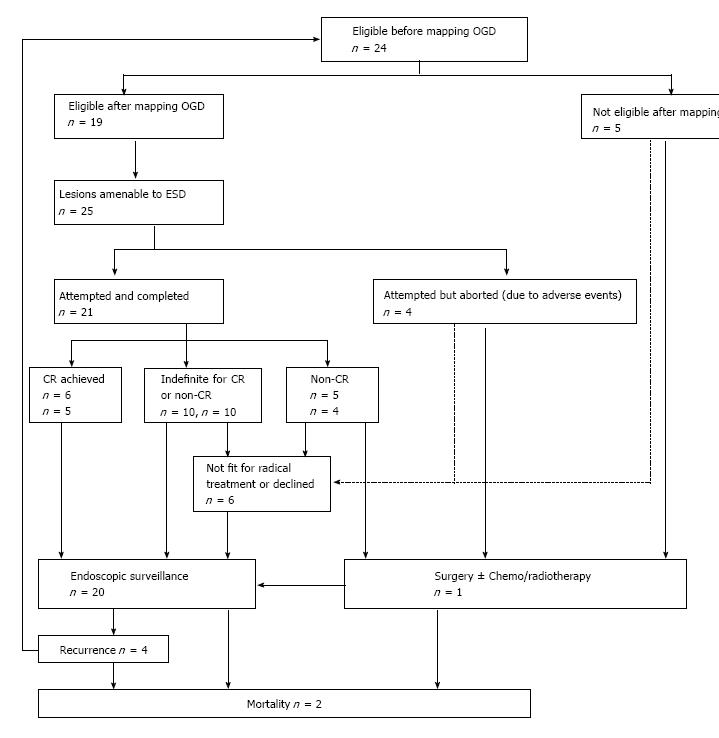

There were 24 patients with gastric dysplasia and/or neoplasia who were considered for endoscopic treatment using ESD. The demographic data of patients included in the study are shown in Table 1. Out of the 24 patients identified for the study, 19 were deemed suitable for ESD after mapping OGD. ESD was attempted on a total of 25 dysplastic or neoplastic lesions, among which 21 were completed and the patients then followed up or offered further treatment based on histology of the resected specimens, and 4 aborted (Figure 1). There were 5 patients who were found to be unsuitable for ESD after mapping OGD.

| Variable | Value, n = 24 |

| Number of patients assessed for ESD, n | 24 |

| Age, Mean ± SD, yr | 73.0 ± 10.7 |

| Age, range, yr | 44-86 |

| Gender, male | 20 (83.3) |

| Gender, female | 4 (16.7) |

| Caucasian ethnicity | 24 (100) |

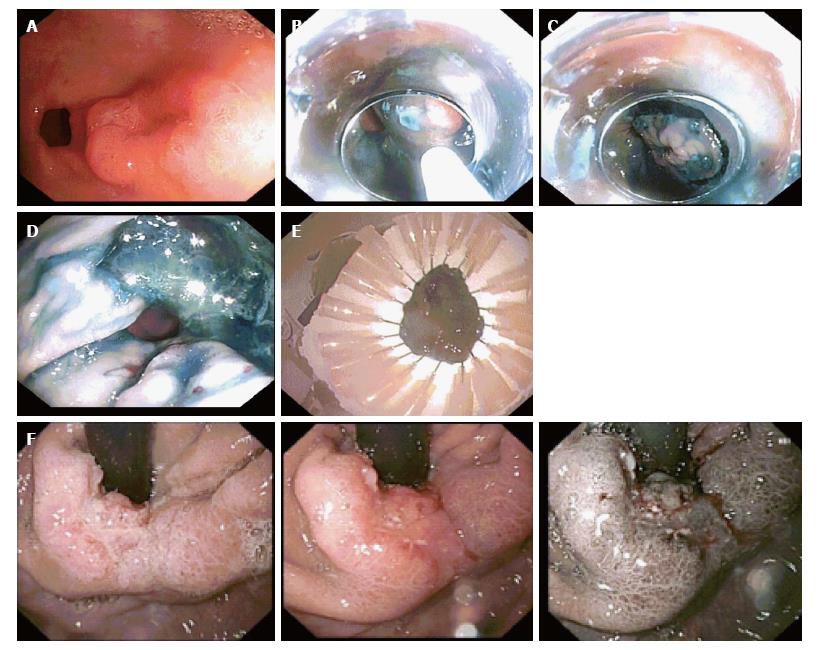

Most lesions were reported as Kato 1, one lesion as Kato 2 and one as Kato 2 to 3. The mean size of lesions resected was 24.7 mm (standard deviation 11.7 mm; range 10-50 mm). Figure 2 shows a lesion suitable for ESD and the procedure in sequence. The main contraindicative features in lesions unsuitable for ESD were ulceration and poor differentiation. Poor lift, large size and deeper invasion constituted other contraindications (Table 2; Figure 2). In one patient, a severe oesophageal stricture prevented passage of the endoscope to assess the lesion. Features of the lesions deemed suitable for ESD are shown in Table 3.

| Patient | Reasons |

| A | Ulcerated lesion |

| B | SM3 or deeper invasion; Poorly differentiated lesion |

| C | Large size: 4-5 cm; Ulcerated over 3 cm |

| D | Severe oesophageal stricture prevented passage of scope |

| E | KATO 3; Deeply ulcerated; Poorly differentiated |

| Variable | Value, n = 25 |

| Location of lesion | |

| Upper stomach | 4 (16) |

| Mid stomach | 7 (28) |

| Lower stomach | 14 (56) |

| Average of longer axis of lesion (mm) | |

| Mean ± SD | 24.7 ± 11.7 |

| Range | 10-50 |

| Histological grade at baseline | |

| IMC | 13 (52) |

| HGD | 8 (32) |

| LGD | 3 (12) |

| Invasive | 1 (4) |

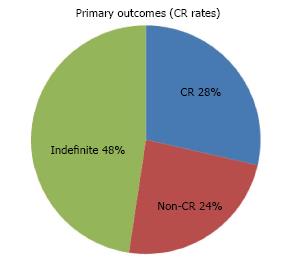

Of the 21 resections completed successfully, en-bloc resection was achieved in 71.4% of cases. Resection was considered complete on endoscopy in 90.5% of cases compared to only 38.1% on histology (Table 4). 6 achieved a definite CR (5 patients), 5 were confirmed to be non-curative (4 patients) and 10 were indefinite (10 patients) (Figure 3). In the latter group, only 2 patients were considered potential candidates for surgery. The rest were only offered endoscopic follow-up as complete resection had been achieved on endoscopy and no other poor prognostic features (e.g., poor differentiation) were present. Adjuvant chemo or radio therapy were not given as patients initially selected for this study had no evidence of lymph node involvement or distant metastases on CT and/or PET-CT scans. The histological diagnoses of non-CR patients post ESD are shown in Table 5.

| Variable | Value, n = 21 |

| Average number of ESD per patient (including failed ESD) | 1.3 |

| Number of en-bloc resections | 15 (71.4) |

| Number of pieces in which lesions were resected | |

| Mean ± SD | 1.5 ± 1.4 |

| Range | 1-7 |

| Unspecified but > 1 | 2 |

| Rate of complete resection on endoscopy | 19 (90.5) |

| Rate of complete resection on histology | 8 (38.1) |

| Margins clear on histology of ESD specimen | |

| Both VM and HM | 8 (38.1) |

| VM only | 1 (4.8) |

| HM only | 1 (4.8) |

| Neither VM nor HM | 1 (4.8) |

| Not specified or difficult to interpret specimen due to coagulation effect/poor preservation of tissue | 10 (47.6) |

| Patient | Histological grade at baseline | Histopathologic diagnosis on ESD specimen of non-CR |

| A | IMC | IMC with lympho-vascular invasion |

| A | IMC | Invasive adenocarcinoma; Lympho-vascular invasion |

| B | IMC | Invasive adenocarcinoma; Poorly differentiated; Diffuse (signet ring) type; Tumour extends into submucosa; Further de-differentiation noted at the invasive aspect |

| C | Highly suspicious of IMC | Adenocarcinoma with deep margin involvement; Moderately to poorly differentiation; Vascular invasion |

| D | Invasive adenocarcinoma | Invasive adenocarcinoma; Well differentiated; No lympho-vascular invasion |

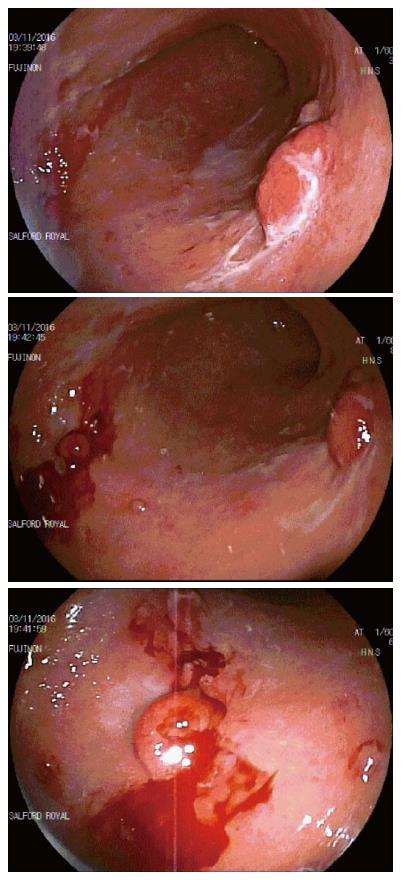

Complications are classified as acute (during the procedure), early (< 48 h after the procedure) or late (> 48 h after the procedure). The most common acute complication reported was oozing small blood vessels (6). In 4 of these cases, bleeding was mild and treated with argon, coagulation forceps or endo-clips. In the other 2, the procedure had to be aborted due to profuse bleeding. Both cases were in the same patient. The patient was on anti-coagulation for atrial fibrillation and had a normal INR after stopping warfarin for 5 d prior to ESD. The marked mucosal friability resulted in bleeding even on mild trauma from the water jet used during endoscopy (Figure 4). A further 2 cases also had to be aborted, one due to the location of the lesion, which would have led to gastric outlet obstruction in due course and the other due to extensive scarring secondary to a previous ESD attempt. There was only one case of early complication involving vomiting within 24 h of the procedure. No cases of late complications were reported.

The median duration of the ESD procedures was found to be 120 min (with factors such as the size of the lesion, its location and tissue factors influencing the length of time required to complete the procedure).

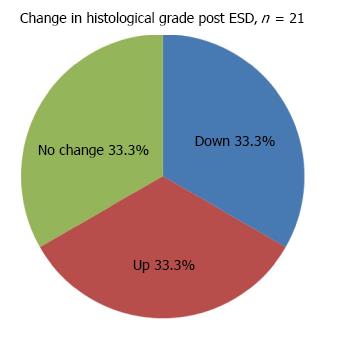

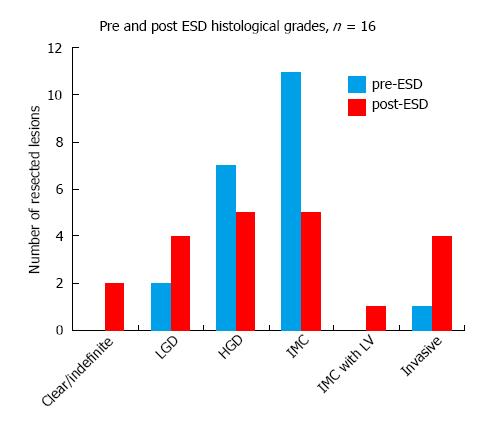

Gastric ESD changed the histological grade in 66.6% of the resected lesions (n = 21) (Figure 5), equally downgrading and upgrading the histological diagnoses. Most resected specimens were found to have HGD (5) and IMC (5), compared to the higher proportion of IMC prior to ESD. In addition, as shown in Figure 6, lympho-vascular invasion and invasive cancer were observed in 5 cases compared to only one case pre ESD. Of these 5 cases, 1 resection was found to be completely clear of dysplasia and a further case indefinite for any dysplasia on histology, but with clear evidence of invasion in both cases. LGD was present in 4 cases. In all cases except one, the change in histological grade, if any, was by one stage.

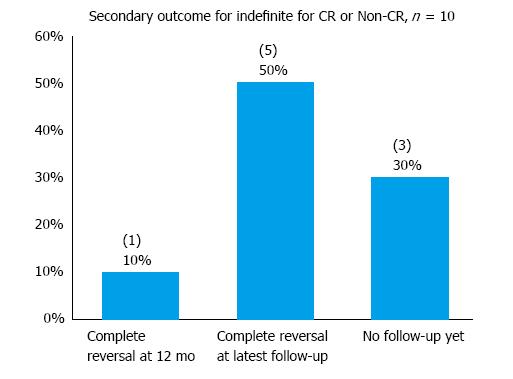

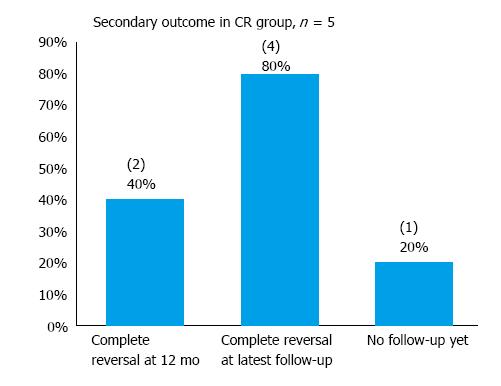

In the “indefinite” cohort of 10 patients, one declined further endoscopic follow-up and has been scheduled for a CT scan instead. In addition, 2 patients had not had any follow-up yet at the time of data collection. One passed away 1 mo after his last follow-up endoscopy (the cause of death is unrelated to his gastric diagnosis). The median follow-up period was 2 mo and the mean 5.1 mo for the “indefinite” cohort (Table 6). Complete reversal of dysplasia was observed in 10% and 50% of patients at 12-mo and the latest follow-up respectively in the “indefinite” cohort (Figure 7). Recurrence was observed in 2 patients - both had in fact been considered poor candidates for ESD at baseline due to multiple comorbidities. In the cohort considered to have achieved CR with ESD, 80% were found to be free of dysplasia at their latest endoscopic follow-up at a mean follow-up period of 6.8 mo (Figure 8). Hence, with both cohorts (CR and ‘indefinite’) combined, 9 of the 11 patients (81.8%) who had had at least one endoscopic follow-up were found to be free of dysplasia on endoscopy at their latest follow-up at a mean follow-up period of 7.7 mo.

| Variable | Indefinite, n = 10 | CR, n = 5 |

| Number of patients under endoscopic follow-up, n (%) | 9 (90) | 5 (100) |

| Median follow-up, mo | 2 | 3 |

| Mean follow-up, mo | 5.1 | 8.5 |

| Range, mo | 0-19 | 0-22 |

| Length of time since ESD, mean ± SD, mo | 13.3 ± 11.3 | 12.2 ± 11.1 |

| Length of time since ESD, range, mo | 2 - 38 | 0 - 26 |

| Number of patients with metachronous or synchronous disease post ESD, n | 2 | 0 |

Overall, 6 patients were considered for surgery after ESD. In the “indefinite” group, the 2 patients with recurrence at follow-up were referred for surgery but neither was sufficiently fit to proceed. ESD was attempted again but failed in both patients. They were thus listed for endoscopic surveillance. Metachronous or recurrent polyps were observed at the latest follow-up for both patients at 11 and 19 mo respectively. In the group of 4 patients found to be non-CR, surgery was considered a treatment option in all of them but only one patient was sufficiently fit to proceed with gastrectomy. The rest of non-CR patients were offered either further ESD or endoscopic surveillance or palliative care.

Only 2 of the 5 patients considered unfit for ESD underwent surgery (Patients B and E; Table 2). Post-op staging were pT3N3MxR1 and pT1bN1MxR0 (moderate to poor differentiation) respectively.

One ESD patient died 4 mo after ESD. ESD on this patient was considered curative and endoscopic follow-up at 3 mo post ESD showed no macroscopic recurrence but biopsies could not be taken due to the patient’s high INR. Cause of death is unrelated to his primary gastric diagnosis. Survival rate in ESD patients was 94.7% (18 out of 19 patients) at a mean follow-up period of 15 mo.

Another patient in the group found unsuitable for ESD died 5 mo after an attempted mapping OGD. The patient was suffering from a severe oesophageal stricture and was receiving parenteral nutrition. The overall survival rate in the entire cohort was thus 91.7% (22 out of 24 patients).

Despite the small sample size, the ability of ESD to achieve CR in carefully selected patients has been demonstrated. Approximately 28% of ESD resections (6) were considered curative. Moreover, 4 of the 5 CR patients were free of dysplasia at the latest follow-up while the fifth patient had not had any follow-up yet, thus corroborating previous studies that demonstrated the positive long-term outcomes in patients with a CR, as defined by the JGCA criteria.

Positive long-term outcomes were also observed in a large proportion of the “indefinite” patients, despite the inability to confirm CR on histology. In the 2 patients who had recurrence of disease, histological evaluation of the ESD specimens had been particularly challenging due to marked inflammation in one case and very severe distortion of the tissue in the other. The specimen in fact reached the pathology laboratory outside formalin. Non-CR could therefore not be confidently excluded in these 2 patients and was in fact made more likely by a pre-ESD diagnosis of IMC. It was clear however on endoscopic follow-ups that these 2 patients had more advanced disease than suspected prior to ESD, as suggested by the presence of several metachronous and/or synchronous - polyps. Overall, despite the inability to always confirm CR on histology, gastric ESD has proven itself highly effective at clearing neoplastic growth if complete resection can be achieved on endoscopy. It also points to the importance of MDT discussions to avoid unnecessary surgery in patients indefinite for CR or non-CR.

The main reason for uncertainty regarding the completeness of excision on histology was the poor preservation of the resected specimens. In many instances, the specimen had been pinned down too deeply into the polystyrene board thus inflicting substantial trauma to the tissue. Other artefacts such as diathermy changes at the periphery, excision margins not clearly defined and inflammation also hindered accurate interpretation. In one case, the lesion had to be resected piecemeal. Other reasons included missing report and lack of mention of margin clearance. Hence, it is clear that to allow for the efficacy of ESD to be more accurately investigated in the future, ways to satisfactorily preserve the resected specimen in its original state and implementing a more systematic approach to reporting histological findings are required.

This study also demonstrates the importance of careful selections of patients at baseline. Out of the 5 non-CR resections, 3 already contained poor prognostic features at baseline. However, the MDT consensus was to proceed with ESD given the patients’ multiple co-morbidities that made them unfit for surgery. In one case, poor differentiation was seen prior to ESD while in the other two, invasive carcinoma had been identified. In the rest of non-CR cases, deeper invasion would have been left unnoticed had the lesion not been resected by ESD. ESD effectively identified lympho-vascular invasion in these 2 lesions presumed to be IMC only prior to ESD. This observation lends support to the status of ESD as the only definitive tool to exclude invasion. Moreover, ESD changed the histological grade in 66.6% of resected lesions. Unlike more large-scale studies however, ESD equally downgraded and upgraded histological diagnoses. In one exceptional case, the histological grade changed from IMC pre-ESD to clear of any dysplasia or malignancy post ESD. Further investigations into this case revealed observer bias in the interpretation of pre-ESD biopsy specimen at the patient’s local hospital. ESD thus enabled the correct diagnosis to be made. This however points to a potential source of error in this study, i.e., bias in interpretation of histology slides.

Only one patient underwent surgery after a non-CR ESD. Interestingly, in this patient, the ESD scar was still present on endoscopic follow-up after the surgery. Deep biopsies taken from this site were all found to be clear of dysplasia, even at the latest endoscopy performed 30 mo post ESD. In this patient, ESD had revealed a well-differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma without any lympho-vascular invasion. This “invasion” constituted the indication for surgery even though the exact depth of invasion was not reported. Hence, it may be possible that ESD patients are being unnecessarily referred for surgery and that ESD alone could be sufficient to treat more advanced diseases with the advantage of shorter hospital stays and fewer complications.

Some of the other limitations of this study include relatively short follow-up periods preventing more accurate assessment of the long-term outcomes and potential bias in letters and endoscopy reports. Hence we plan to study a larger number of patients and have a longer follow-up period in order to reduce bias and truly assess the efficacy of ESD in our Caucasian United Kingdom population.

In conclusion, these results although modest are promising and provide early evidence in favour of the use of ESD in Caucasian populations in the United Kingdom. Despite the wealth of evidence for the efficacy of gastric ESD in Far Eastern countries, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) United Kingdom still views upper GI ESD as a procedure to be applied on a case-by-case basis only with an MDT approach[22], thus demonstrating the need for further, larger-scale studies into this technique in the United Kingdom and other Western countries.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a minimally invasive technique used to treat early superficial lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. It is popular in Far East countries where its outstanding efficacy has been proven by multiple studies. Technological advances have recently made ESD more accessible worldwide. In the United Kingdom, this intervention is still relatively new and local evidence to support its use still scarce.

This study aims to evaluate the application of ESD in Caucasian patients in the United Kingdom and seeks to compensate for the lack of evidence in the literature in favour of its use in this country. Larger scale studies will be required in the future.

This study constitutes a step forward in providing the evidence necessary to support the application of ESD among Caucasian patients in the United Kingdom as well as to help produce standardised clinical guidelines to inform local clinical practice for this relatively new intervention.

This retrospective study uses data obtained from the Department of Gastroenterology at Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust in the United Kingdom, a tertiary centre for gastrointestinal interventions. Data for a period of 2 years has been analysed using Microsoft Excel.

Of the 21 lesions resected with ESD, 6 achieved curative resection (CR), 10 were “indefinite” for CR or non-CR, and 5 were considered non-CR. A favourable long-term outcome was observed in the CR and “indefinite” groups, with clearance of dysplasia observed overall in 81.8% of patients who had had at least one endoscopic follow-up. ESD also changed the histological diagnoses in 66.6% of cases. These results are promising and provide early evidence in favour of the use of ESD in the United Kingdom.

ESD as applied to Caucasian patients in the United Kingdom can produce promising results as shown by this study. There have not been similar studies in the United Kingdom in the past and thus larger scale studies are required to fully evaluate the efficacy and safety profile of ESD as applied to upper gastrointestinal cancers.

To better assess the effectiveness of ESD at clearing early neoplastic lesions of the stomach and other upper gastrointestinal cancers among Caucasian patients in the United Kingdom, a prospective study involving a larger sample of such patients is required.

We acknowledge the hospital coding department for their help in identifying patients for this study. We acknowledge the Upper GI specialist multi-disciplinary team for their contributions to discussions for patient selection for the ESD procedures. We acknowledge the helpful discussions from Mr Ram Chaparala, Ms Rachel Melhedo, our radiology, oncology and pathology colleagues.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Braden B, Coskun A, Rabago L, Trifan A S- Editor: Chen K L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Takekoshi T, Baba Y, Ota H, Kato Y, Yanagisawa A, Takagi K, Noguchi Y. Endoscopic resection of early gastric carcinoma: results of a retrospective analysis of 308 cases. Endoscopy. 1994;26:352-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon T, Repici A, Vieth M, De Ceglie A, Amato A, Berr F, Bhandari P, Bialek A. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:829-854. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 817] [Cited by in RCA: 927] [Article Influence: 92.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Uedo N, Takeuchi Y, Ishihara R. Endoscopic management of early gastric cancer: endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection: data from a Japanese high-volume center and literature review. Ann Gastroenterol. 2012;25:281-290. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Cao Y, Liao C, Tan A, Gao Y, Mo Z, Gao F. Meta-analysis of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection for tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 2009;41:751-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Takeuchi Y, Uedo N, Iishi H, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto S, Yamada T, Higashino K, Ishihara R, Tatsuta M, Ishiguro S. Endoscopic submucosal dissection with insulated-tip knife for large mucosal early gastric cancer: a feasibility study (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:186-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gotoda T. A large endoscopic resection by endoscopic submucosal dissection procedure for early gastric cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S71-S73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Park YM, Cho E, Kang HY, Kim JM. The effectiveness and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2666-2677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hull MJ, Mino-Kenudson M, Nishioka NS, Ban S, Sepehr A, Puricelli W, Nakatsuka L, Ota S, Shimizu M, Brugge WR. Endoscopic mucosal resection: an improved diagnostic procedure for early gastroesophageal epithelial neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:114-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yoshinaga S, Oda I, Nonaka S, Kushima R, Saito Y. Endoscopic ultrasound using ultrasound probes for the diagnosis of early esophageal and gastric cancers. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:218-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pech O, May A, Manner H, Behrens A, Pohl J, Weferling M, Hartmann U, Manner N, Huijsmans J, Gossner L. Long-term efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection for patients with mucosal adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:652-660.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Peters F, Brakenhoff K, Curvers W, Rosmolen W, Fockens P, ten Kate F, Krishnadath K, Bergman J. Histologic evaluation of resection specimens obtained at 293 endoscopic resections in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:604–609. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pech O, Gossner L, Manner H, May A, Rabenstein T, Behrens A, Berres M, Huijsmans J, Vieth M, Stolte M. Prospective evaluation of the macroscopic types and location of early Barrett’s neoplasia in 380 lesions. Endoscopy. 2007;39:588-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Merkow R, Bilimoria K, Keswani R, Chung J, Sherman K, Knab L, Posner M, Bentrem D. Treatment trends, risk of lymph node metastasis, and outcomes for localized esophageal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Buskens C, Westerterp M, Lagarde S, Bergman J, ten Kate F, van Lanschot J. Prediction of appropriateness of local endoscopic treatment for high-grade dysplasia and early adenocarcinoma by EUS and histopathologic features. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chiu PW, Teoh AY, To KF, Wong SK, Liu SY, Lam CC, Yung MY, Chan FK, Lau JY, Ng EK. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) compared with gastrectomy for treatment of early gastric neoplasia: a retrospective cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3584-3591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Nimura S, Yahagi N, Iishi H, Oka M, Ajioka Y, Ichinose M. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 406] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | 1 Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1575] [Cited by in RCA: 1914] [Article Influence: 239.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Toyonaga T, Man-i M, East JE, Nishino E, Ono W, Hirooka T, Ueda C, Iwata Y, Sugiyama T, Dozaiku T. 1,635 Endoscopic submucosal dissection cases in the esophagus, stomach, and colorectum: complication rates and long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1000-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Oda I, Suzuki H, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S. Complications of gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2013;25 Suppl 1:71-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chiu PW. Novel endoscopic therapeutics for early gastric cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:120-125. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Probst A, Pommer B, Golger D, Anthuber M, Arnholdt H, Messmann H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric neoplasia - experience from a European center. Endoscopy. 2010;42:1037-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | National institute for health and clinical excellence, N. I.C.E. 2015. Interventional procedures programme interventional procedure overview of endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric lesions. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg360/evidence/overview-pdf-495581293. |

| 23. | Chung IK, Lee JH, Lee SH, Kim SJ, Cho JY, Cho WY, Hwangbo Y, Keum BR, Park JJ, Chun HJ. Therapeutic outcomes in 1000 cases of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: Korean ESD Study Group multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1228-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 429] [Cited by in RCA: 476] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kato H, Haga S, Endo S, Hashimoto M, Katsube T, Oi I, Aiba M, Kajiwara T. Lifting of lesions during endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) of early colorectal cancer: implications for the assessment of resectability. Endoscopy. 2001;33:568-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Cooper HS, Dawsey SM, Dixon MF, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Fléjou JF, Geboes K. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut. 2000;47:251-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1463] [Cited by in RCA: 1548] [Article Influence: 61.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |