Published online Apr 16, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i4.346

Peer-review started: September 6, 2014

First decision: November 27, 2014

Revised: December 9, 2014

Accepted: January 9, 2015

Article in press: January 12, 2015

Published online: April 16, 2015

Processing time: 225 Days and 19.2 Hours

Type I gastric neuroendocrine tumors (TI-GNETs) are related to chronic atrophic gastritis with hypergastrinemia and enterochromaffin-like cell hyperplasia. The incidence of TI-GNETs has significantly increased, with the great majority being TI-GNETs. TI-GNETs present as small (< 10 mm) and multiple lesions endoscopically and are generally limited to the mucosa or submucosa. Narrow band imaging and high resolution magnification endoscopy may be helpful for the endoscopic diagnosis of TI-GNETs. TI-GNETs are usually histologically classified by World Health Organization criteria as G1 tumors. Therefore, TI-GNETs tend to display nearly benign behavior with a low risk of progression or metastasis. Several treatment options are currently available for these tumors, including surgical resection, endoscopic resection, and endoscopic surveillance. However, debate persists about the best management technique for TI-GNETs.

Core tip: The incidence of type I gastric neuroendocrine tumors (TI-GNETs) has significantly increased, TI-GNETs are the most frequently diagnosed of all GNETs, accounting for about 70%-80%. Endoscopically, TI-GNETs are present as small (< 10 mm), polypoid lesions or, more frequently, as smooth, rounded submucosal lesions. Especially, narrow band imaging and high resolution magnification endoscopy may be helpful for the endoscopic diagnosis of TI-GNETs. TI-GNETs tend to display a nearly benign behavior and a low risk of progression or metastasis in spite of submucosal invasion. Therefore, endoscopic submucosal dissection is a feasible technique for the removal of TI-GNETs.

- Citation: Sato Y. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of type I neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(4): 346-353

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i4/346.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i4.346

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), originally termed carcinoid tumors, arise from neuroendocrine cells of the diffuse neuroendocrine system[1]. NETs are rare neoplasms; however, the incidence of gastrointestinal NETs (GNET) is gradually increasing with all NETs[2,3], while the ratio of GNETs to all GI NETs has increased according to the latest reports[4-9]. This increase in the incidence of GNETs reflects the true increase (that the incidence of GNET is increasing); however, this also might be related to improvements in diagnostic technology including endoscopy and increased GNET awareness. Because of the increasing incidence and prevalence, GNETs represent a substantial clinical problem.

GNETs are classified into three distinct subgroups: types I to III[10]. Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of these three types[11-19]. Type I GNETs (TI-GNETs) arise in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG), including autoimmune gastritis (AIG; i.e., type-A gastritis) and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-associated atrophic gastritis. Most TI-GNETs are small (< 10 mm), multiple, located within the gastric fundus or corpus, and limited to the mucosa or submucosa. TI-GNETs comprise the great majority (70%-80%) of GNETs. TI-GNETs are generally considered benign, with low metastasis rates and a 100% long-term survival rate.

| Characteristic | Type I GNETs | Type II GNETs | Type III GNETs |

| Proportion of all GNETs | 70%-80% | 5%-10% | 10%-15% |

| Associated disease | Chronic atrophic gastritis | MEN type 1/ZES | None |

| Gender | Women > men | Women = men | Women < men |

| Tumor number | ≥ 1 | ≥ 1 | 1 |

| Tumor size | < 10 mm | < 10 mm | Often > 20 mm |

| Tumor location | Fundus or corpus | Fundus or corpus | Any region |

| Histology | Well differentiated | Well differentiated | From well to poorly differentiated |

| Invasion depth | Mucosa or submucosa | Mucosa or submucosa | Any depth |

| Serum gastrin level | High | High | Normal |

| Gastric pH | Low | High | Normal |

| Metastasis risk | 2%-5% | 10%-20% | > 50% |

| Tumor-related death | 0 | < 10% | 25%-30% |

| Prognosis | Excellent | Good | Poor |

Type II GNETs, which account for 5%-6% of all GNETs, are associated with the gastrin-secreting neoplasms in multiple endocrine neoplasia-Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (MEN-ZES). Therefore, hyperacidity-induced peptic ulceration is often seen in patients with type II GNETs. Type II GNETs are also small, multiple, and considered benign. However, the survival rate of patients with type II GNETs is lower than that of patients with type I because of the course of the gastrinoma[20].

On the contrary, type III GNETs are sporadic tumors whose development is unrelated to gastrin conditions. Type III NETs are often single and large, have a diameter around 20 mm, and comprise approximately 10%-15% of all GNETs. These GNETs behave more aggressively and are usually metastatic and spread to the regional lymph nodes or liver.

This review focuses on TI-GNET pathogenesis, endoscopic diagnosis, and management.

TI-GNETs are associated with CAG, which leads to hypergastrinemia and enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell hyperplasia. The loss of fundic glands seen in CAG results in a lack of acid production (achlorhydria). In response to achlorhydria, antral G-cells undergo hyperplasia and secrete more gastrin, resulting in hypergastrinemia. Gastrin stimulates gastric epithelial cell proliferation and acts as a trophic factor for ECL cells and leads to ECL cell hyperplasia. Therefore, hypergastrinemia results in the progression to TI-GNET development.

In either AIG- or H. pylori-associated gastritis, under the CAG condition, a lack of gastric acid production results in hypergastrinemia and leads to TI-GNET progression. In the AIG, anti-parietal cell antibody acts on gastric parietal cells, leading to acid secretion disorder and resulting in more gastrin secretion by antral G-cells. The role of H. pylori in TI-GNET development is unclear. However, it is well known that H. pylori infection induces hypergastrinemia[21,22]. H. pylori induces gastric mucosal atrophy, resulting in low acid output[23]. The negative feedback loop created by this low acid output causes hypergastrinemia. One possible mechanism is that antibodies against H. pylori may act like those against parietal cells[24-26]. Furthermore, H. pylori lipopolysaccharide stimulates DNA synthesis in ECL cells, suggesting that it may contribute to ECL cell hyperplasia[27]. Some reports have suggested that H. pylori infection might be a risk factor for TI-GNET in humans due to hypergastrinemia[28,29]. However, a minority of patients with CAG had TI-GNETs; therefore, it has been proposed that other cofactors (i.e., Reg[30], mcl-1[31], MEN-1 gene mutation[32]) might play a role in TI-GNET development.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPI) create hypergastrinemia secondary to gastric hypoacidity. Therefore, PPI treatment causes ECL hyperplasia in rats[33,34]. In humans, there are some case reports of GNETs that developed after long-term PPI treatment[35-38], and one revealed disappearance of the tumors after PPI treatment discontinuation[38]. However, the number of reports about GNETs compared to those on PPI users remains very small, and it is generally accepted that continual PPI use is not associated with GNET development in humans.

Most patients with TI-GNETs have no specific symptoms related to “carcinoid syndrome”[39,40] such as flushing, tachycardia, and diarrhea. However, those with TI-GNET have nonspecific symptoms (nausea, abdominal pain, dyspepsia)[41] or pernicious anemia complicated by AIG. Therefore, TI-GNETs are detected incidentally during esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

TI-GNETs are more prevalent in women[14,16], a finding that is attributed to the fact that AIG occurs more commonly in females[42]. AIG is also substantially more common in patients with other autoimmune-related diseases (type 1 diabetes mellitus[43], autoimmune thyroiditis[44], and primary biliary cirrhosis[45]) than in the healthy population. Therefore, the existence of TI-GNETs should be also appropriately investigated in patients with those diseases. Moreover, under the condition of CAG, the stomach becomes unable to produce sufficient amounts of pepsinogen and pepsin due to gastric chief cell injury. Therefore, patients with CAG show the low pepsinogen I level and pepsinogen I/II ratio on serological testing[46], while the measurement of pepsinogen I level and pepsinogen I/II ratio might be helpful for distinguishing TI-GNETs from the other two GNET types.

Serum chromogranin A (CgA) levels are increased in patients with TI-GNETs[39]. However, an elevated serum CgA level is not specific to GNETs. Therefore, measuring CgA is not recommended as a routine screening but rather as a surveillance marker for monitoring GNET progression.

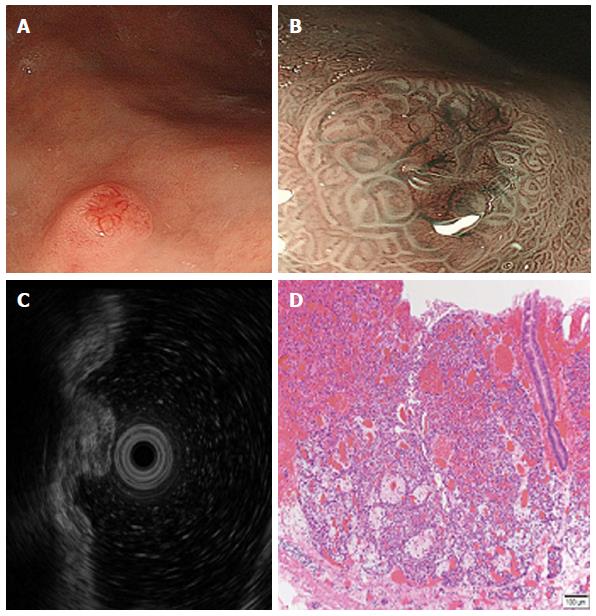

TI-GNETs are often small (< 10 mm), multiple, and found in the gastric corpus or fundus. Endoscopically, TI-GNETs present as polypoid lesions or, more frequently, as smooth and rounded submucosal lesions[47] and may appear yellow or red in color. A depression can sometimes be seen at the center of the tumor. The use of high-resolution magnifying endoscopy (ME) and narrow band imaging (NBI) might be helpful for the endoscopic diagnosis of GNETs[48]. The ME with NBI approach provides very clear images of the fine superficial structure and microvasculature of the gastric mucosa. Endoscopic TI-GNET images are shown in Figure 1. Endoscopy with white light revealed a hemispherical reddish polyp with or without a central depression (Figure 1A). Most of the GNET surface is covered with normal mucosa; therefore, gastric pits can be visualized in ME using the NBI system. However, in the area of the central depression, gastric glands vanish, so the gastric pits cannot be visualized. The tumor grows expansively beneath the epithelium; therefore, abnormally dilated subepithelial vessels with blackish-brown or cyan corkscrew-shaped capillaries are visible (Figure 1B). This finding reflects the fact that the tumor grew beneath the epithelium without a gland structure. Differential diagnoses include gastric lymphoma and metastatic lesions (breast cancer, lung cancer, and melanoma), which also present as protruding tumors covered with non-tumorous mucosa.

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is useful for judging GNET invasion depth[49]. On EUS, GNETs are commonly seen in the second (deeper mucosa) or third (submucosa) echo layer and have a hypoechoic intramural structure (Figure 1C). The tumors generally have a hypoechoic structure with uniform echotexture. The tumor margins are typically well defined and smooth, and the overall shape is round and oval. A 20 MHz frequency ultrasound probe is generally useful for the evaluation of small GNETs; however, lesions > 20 mm may require the use of a lower frequency (12 MHz) probe[50].

Additionally, as documented above, the greater portions of these tumors are covered with normal mucosa; therefore, the collection of adequate endoscopic biopsy specimens in the deeper cut is required for diagnosis. Sampling biopsy should be taken of not only the TI-GNET lesion but also each antrum and corpus/fundus to assess for the presence of atrophic gastritis and hyperplastic/dysplastic proliferation of ECL cells as TI-GNET precursors[51].

TI-GNETs are composed of small uniform cells in nests and infiltrating strands with a ribbon-like, tubular, or acinar pattern (Figure 1D). According to the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) consensus proposal in 2006, NETs are classified by counting mitosis and Ki67 index (Table 2)[52]. Based on this grading method, in 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) classification[53], histological classification of NETs is based on proliferation and differentiation: G1 NET, G2 NET, neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC), mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma, and hyperplastic and pre-neoplastic lesions. A G3 tumor classified by ENETS criteria would correspond to NEC on WHO criteria. Histologically, most TI-GNETs are G1 NETs.

| ENETSgrading | Mitotic index(× 10 HPF) | Ki-67 proliferationindex (%) | WHO classification 2010 |

| G1 | < 2 | ≤ 2 | NET G1 (carcinoid) |

| G2 | 2-20 | 3-20 | NET G2 |

| G3 | > 20 | > 20 | NEC G3; large-cell or small-cell type |

Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging can provide useful information about local spread and distal metastasis to aid with tumor staging. The role of fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography is unclear in the assessment of TI-GNETs[54]. Findings of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, also known as an octreoscan, are often negative in TI-GNETs[55] because this method cannot usually identify small GI-NETs.

The clinical management and treatment of TI-GNETs depends on tumor size and the presence of risk factors such as muscular wall infiltration, increased proliferation, and/or metastasis. Simple surveillance or endoscopic resection (ER) is generally recommended for TI-GNETs < 10 mm that have not invaded the muscularis propria or otherwise metastasized. The treatment of TI-GNETs 10-20 mm that are limited to the submucosa is controversial: ENETS guidelines recommend ER, whereas National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines[56] recommend both ER and endoscopic surveillance. Patients with TI-GNETs measuring > 20 mm, or those that have invaded beyond the submucosa, or have multiple lesions that are unsuitable for ER generally require surgical resection.

Hitherto, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) has been recommended and is performed, as it is the most useful method of mucosal resection for local TI-GNETs. However, TI-GNETs frequently invade the submucosa; therefore, they are difficult to remove completely, even when small, using snare polypectomy or conventional EMR. In contrast, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a feasible technique for the removal of tumors such as TI-GNETs within the submucosal layer. Recent reports have shown that the complete resection rate of GNETs using ESD was superior to that using EMR[57,58].

Surgical resection is generally recommended for TI-GNETs > 20 mm in diameter or those that have invaded beyond the submucosa[52,56]. Moreover, surgery should also be performed in the presence of lymph nodal, distant disease spread, or poorly differentiated neoplasms[51]. For surgical therapy, local resection and/or antrectomy to reduce gastrin levels should be chosen. Antrectomy removes G-cell–mediated hypergastrinemia; however, it might not effectively prevent recurrence and/or metastasis[59]. This suggests that TI-GNETs can grow autonomously independent of gastrin and beyond the gastrin responsive growing point. In the case of TI-GNET recurrence or persistence after local resection and antrectomy, total gastrectomy would be needed.

Somatostatin analogs (SSAs) act on G-cells to inhibit gastrin secretion and play a role in reducing ECL cell hyperplasia. SSA treatment effectively reduces TI-GNET number and size[60-62]. However, its use cannot be recommended due to its short-term effects (i.e., the tumor recurs after its cessation)[63] and its relatively high cost. Recently, natazepide (YF476), a peripheral gastrin (CCK-B) receptor antagonist, has been reported to suppress gastric acid output and ECL cell proliferation and reduce TI-GNET size and number[64]. However, there is no study on the long-term administration or large studies on CCK-B receptor antagonist treatment for TI-GNETs.

Patients with TI-GNETs generally have an excellent prognosis; in fact, disease-specific survival approaches 100%[39,40,59,60,65-74]. Tumor size and depth predict lymph node metastasis for GNETs[75], and presence of metastasis was the only factor that influenced long-term prognosis of patients with GNETs[40]. Moreover, histological tumor grading is well correlated with patient survival[68]. Therefore, the assessment of tumor metastasis, size, depth, and histological grade may predict patient prognosis. In fact, metastatic TI-GNETs are related to tumor size ≥ 1 cm, an elevated Ki-67 index, and high serum gastrin levels[76]. On the other hand, TI-GNET recurrence rates are relatively high; however, recurrent lesions are small, indolent, and unrelated to prognosis[39,72].

Post-treatment ENETS guidelines propose that endoscopic surveillance be provided every 12 mo for patients with recurrent TI-GNET and every 24 mo for patients without recurrence[51]. NCCN guidelines recommend that patients with small (< 20 mm) TI-GNETs who did not require ER or treatment be evaluated using patient history and a physical examination every 6-12 mo[56]. The guidelines also recommend that follow-up endoscopy be performed every 6-12 mo for the first 3 years and annually thereafter if no evidence of recurrence or progression is seen[56]. However, an optimal follow-up schedule as a clinical standard has yet to be established.

The incidence of NETs has increased significantly, and the vast majority of NETs are TI-GNETs. TI-GNETs present as small (< 10 mm) and multiple lesions that are generally limited to the mucosa or submucosa. TI-GNETs tend to display a nearly benign behavior and a low risk of progression or metastasis. Several treatment options are currently available for TI-GNETs; however, their optimal management has not yet been established. Further studies on TI-GNETs are needed to develop new promising management strategies for patients with TI-GNETs.

In routine clinical practice, the careful observation of the gastric mucosa in CAG and the knowledge of the endoscopic characteristic of TI-GNETs would be required for detection of TI-GNETs. When it exists, it would be important to choose appropriate treatment after the assessment of the size, invasion, metastasis and histological grading of the tumors.

P- Reviewer: Amornyotin S, Declich P S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Solcia E, Arnold R, Capella C, klimstra DS, Klöppel G, Komminoth P, Rindi G. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the stomach. WHO classification of Tumours of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC 2010; 64-68. |

| 2. | Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, Svejda B, Kidd M, Modlin IM. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1-18, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 600] [Cited by in RCA: 631] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, Abdalla EK, Fleming JB, Vauthey JN, Rashid A. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063-3072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3022] [Cited by in RCA: 3247] [Article Influence: 191.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ellis L, Shale MJ, Coleman MP. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: trends in incidence in England since 1971. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2563-2569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 50-year analysis of 562 gastric carcinoids: small tumor or larger problem? Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:23-32. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ito T, Sasano H, Tanaka M, Osamura RY, Sasaki I, Kimura W, Takano K, Obara T, Ishibashi M, Nakao K. Epidemiological study of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:234-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Niederle MB, Hackl M, Kaserer K, Niederle B. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: the current incidence and staging based on the WHO and European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society classification: an analysis based on prospectively collected parameters. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Cho MY, Kim JM, Sohn JH, Kim MJ, Kim KM, Kim WH, Kim H, Kook MC, Park do Y, Lee JH. Current Trends of the Incidence and Pathological Diagnosis of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (GEP-NETs) in Korea 2000-2009: Multicenter Study. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:157-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Caldarella A, Crocetti E, Paci E. Distribution, incidence, and prognosis in neuroendocrine tumors: a population based study from a cancer registry. Pathol Oncol Res. 2011;17:759-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rindi G, Luinetti O, Cornaggia M, Capella C, Solcia E. Three subtypes of gastric argyrophil carcinoid and the gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:994-1006. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Nikou GC, Angelopoulos TP. Current concepts on gastric carcinoid tumors. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:287825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Basuroy R, Srirajaskanthan R, Prachalias A, Quaglia A, Ramage JK. Review article: the investigation and management of gastric neuroendocrine tumours. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1071-1084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li TT, Qiu F, Qian ZR, Wan J, Qi XK, Wu BY. Classification, clinicopathologic features and treatment of gastric neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:118-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Massironi S, Sciola V, Spampatti MP, Peracchi M, Conte D. Gastric carcinoids: between underestimation and overtreatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2177-2183. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Zhang L, Ozao J, Warner R, Divino C. Review of the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of type I gastric carcinoid tumor. World J Surg. 2011;35:1879-1886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Scherübl H, Cadiot G, Jensen RT, Rösch T, Stölzel U, Klöppel G. Neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach (gastric carcinoids) are on the rise: small tumors, small problems? Endoscopy. 2010;42:664-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kaltsas G, Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Alexandraki KI, Thomas D, Tsolakis AV, Gross D, Grossman AB. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of type 1 gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2014;81:157-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | O’Toole D, Delle Fave G, Jensen RT. Gastric and duodenal neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:719-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dakin GF, Warner RR, Pomp A, Salky B, Inabnet WB. Presentation, treatment, and outcome of type 1 gastric carcinoid tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:368-372. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Meko JB, Norton JA. Management of patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Annu Rev Med. 1995;46:395-411. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Chittajulla RS, Ardill JES, McColl KEL. The degree of hypergastrinemia induced by Helicobacter pylori is the same in duodenal ulcer patients and asymptomatic volunteers. Eur J Gastroenterol. 1992;4:49-53. |

| 22. | Smith JT, Pounder RE, Nwokolo CU, Lanzon-Miller S, Evans DG, Graham DY, Evans DJ. Inappropriate hypergastrinaemia in asymptomatic healthy subjects infected with Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1990;31:522-525. [PubMed] |

| 23. | El-Omar EM, Oien K, El-Nujumi A, Gillen D, Wirz A, Dahill S, Williams C, Ardill JE, McColl KE. Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic gastric acid hyposecretion. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:15-24. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Faller G, Steininger H, Kränzlein J, Maul H, Kerkau T, Hensen J, Hahn EG, Kirchner T. Antigastric autoantibodies in Helicobacter pylori infection: implications of histological and clinical parameters of gastritis. Gut. 1997;41:619-623. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Claeys D, Faller G, Appelmelk BJ, Negrini R, Kirchner T. The gastric H+,K+-ATPase is a major autoantigen in chronic Helicobacter pylori gastritis with body mucosa atrophy. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:340-347. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Negrini R, Savio A, Poiesi C, Appelmelk BJ, Buffoli F, Paterlini A, Cesari P, Graffeo M, Vaira D, Franzin G. Antigenic mimicry between Helicobacter pylori and gastric mucosa in the pathogenesis of body atrophic gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:655-665. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Kidd M, Miu K, Tang LH, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ, Sandor A, Modlin IM. Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide stimulates histamine release and DNA synthesis in rat enterochromaffin-like cells. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1110-1117. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Solcia E, Rindi G, Fiocca R, Villani L, Buffa R, Ambrosiani L, Capella C. Distinct patterns of chronic gastritis associated with carcinoid and cancer and their role in tumorigenesis. Yale J Biol Med. 1992;65:793-804; discussion 827-829. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Sato Y, Iwafuchi M, Ueki J, Yoshimura A, Mochizuki T, Motoyama H, Sugimura K, Honma T, Narisawa R, Ichida T. Gastric carcinoid tumors without autoimmune gastritis in Japan: a relationship with Helicobacter pylori infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:579-585. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Higham AD, Bishop LA, Dimaline R, Blackmore CG, Dobbins AC, Varro A, Thompson DG, Dockray GJ. Mutations of RegIalpha are associated with enterochromaffin-like cell tumor development in patients with hypergastrinemia. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1310-1318. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Pritchard DM, Berry D, Przemeck SM, Campbell F, Edwards SW, Varro A. Gastrin increases mcl-1 expression in type I gastric carcinoid tumors and a gastric epithelial cell line that expresses the CCK-2 receptor. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G798-G805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | D’Adda T, Keller G, Bordi C, Höfler H. Loss of heterozygosity in 11q13-14 regions in gastric neuroendocrine tumors not associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome. Lab Invest. 1999;79:671-677. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Bakke I, Qvigstad G, Brenna E, Sandvik AK, Waldum HL. Gastrin has a specific proliferative effect on the rat enterochromaffin-like cell, but not on the parietal cell: a study by elutriation centrifugation. Acta Physiol Scand. 2000;169:29-37. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Larsson H, Carlsson E, Mattsson H, Lundell L, Sundler F, Sundell G, Wallmark B, Watanabe T, Håkanson R. Plasma gastrin and gastric enterochromaffinlike cell activation and proliferation. Studies with omeprazole and ranitidine in intact and antrectomized rats. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:391-399. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Dawson R, Manson JM. Omeprazole in oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet. 2000;356:1770-1771. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Haga Y, Nakatsura T, Shibata Y, Sameshima H, Nakamura Y, Tanimura M, Ogawa M. Human gastric carcinoid detected during long-term antiulcer therapy of H2 receptor antagonist and proton pump inhibitor. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:253-257. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Jianu CS, Fossmark R, Viset T, Qvigstad G, Sørdal O, Mårvik R, Waldum HL. Gastric carcinoids after long-term use of a proton pump inhibitor. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:644-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Ravizza D, Fiori G, Trovato C, Fazio N, Bonomo G, Luca F, Bodei L, Pelosi G, Tamayo D, Crosta C. Long-term endoscopic and clinical follow-up of untreated type 1 gastric neuroendocrine tumours. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:537-543. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Borch K, Ahrén B, Ahlman H, Falkmer S, Granérus G, Grimelius L. Gastric carcinoids: biologic behavior and prognosis after differentiated treatment in relation to type. Ann Surg. 2005;242:64-73. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Granberg D, Wilander E, Stridsberg M, Granerus G, Skogseid B, Oberg K. Clinical symptoms, hormone profiles, treatment, and prognosis in patients with gastric carcinoids. Gut. 1998;43:223-228. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Soykan I, Yakut M, Keskin O, Bektaş M. Clinical profiles, endoscopic and laboratory features and associated factors in patients with autoimmune gastritis. Digestion. 2012;86:20-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | De Block CE, De Leeuw IH, Van Gaal LF. Autoimmune gastritis in type 1 diabetes: a clinically oriented review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:363-371. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Lam-Tse WK, Batstra MR, Koeleman BP, Roep BO, Bruining MG, Aanstoot HJ, Drexhage HA. The association between autoimmune thyroiditis, autoimmune gastritis and type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2003;1:22-37. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Mörk H, Jakob F, al-Taie O, Gassel AM, Scheurlen M. Primary biliary cirrhosis and gastric carcinoid: a rare association? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;24:270-273. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Samloff IM, Varis K, Ihamaki T, Siurala M, Rotter JI. Relationships among serum pepsinogen I, serum pepsinogen II, and gastric mucosal histology. A study in relatives of patients with pernicious anemia. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:204-209. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Ichikawa J, Tanabe S, Koizumi W, Kida Y, Imaizumi H, Kida M, Saigenji K, Mitomi H. Endoscopic mucosal resection in the management of gastric carcinoid tumors. Endoscopy. 2003;35:203-206. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Singh R, Yao K, Anagnostopoulos G, Kaye P, Ragunath K. Microcarcinoid tumor diagnosed with high-resolution magnification endoscopy and narrow band imaging. Endoscopy. 2008;40 Suppl 2:E12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Karaca C, Turner BG, Cizginer S, Forcione D, Brugge W. Accuracy of EUS in the evaluation of small gastric subepithelial lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:722-727. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Kojima T, Takahashi H, Parra-Blanco A, Kohsen K, Fujita R. Diagnosis of submucosal tumor of the upper GI tract by endoscopic resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:516-522. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Delle Fave G, Kwekkeboom DJ, Van Cutsem E, Rindi G, Kos-Kudla B, Knigge U, Sasano H, Tomassetti P, Salazar R, Ruszniewski P. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with gastroduodenal neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:74-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Rindi G, Klöppel G, Alhman H, Caplin M, Couvelard A, de Herder WW, Erikssson B, Falchetti A, Falconi M, Komminoth P. TNM staging of foregut (neuro)endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:395-401. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Rindi G, Arnold R, Bosman FT, Capella C, klimstra DS, Klöppel G, Komminoth P, Solcia E. Nomenclature and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system. Lyon: International Agency for Research on cancer (IARC) 2010; 13-14. |

| 54. | Bushnell DL, Baum RP. Standard imaging techniques for neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:153-62, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Gibril F, Reynolds JC, Lubensky IA, Roy PK, Peghini PL, Doppman JL, Jensen RT. Ability of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy to identify patients with gastric carcinoids: a prospective study. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1646-1656. [PubMed] |

| 56. | Kulke MH, Benson AB, Bergsland E, Berlin JD, Blaszkowsky LS, Choti MA, Clark OH, Doherty GM, Eason J, Emerson L. Neuroendocrine tumors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:724-764. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Sato Y, Takeuchi M, Hashimoto S, Mizuno K, Kobayashi M, Iwafuchi M, Narisawa R, Aoyagi Y. Usefulness of endoscopic submucosal dissection for type I gastric carcinoid tumors compared with endoscopic mucosal resection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:1524-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 58. | Kim HH, Kim GH, Kim JH, Choi MG, Song GA, Kim SE. The efficacy of endoscopic submucosal dissection of type I gastric carcinoid tumors compared with conventional endoscopic mucosal resection. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014;2014:253860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 59. | Gladdy RA, Strong VE, Coit D, Allen PJ, Gerdes H, Shia J, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF, Tang LH. Defining surgical indications for type I gastric carcinoid tumor. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3154-3160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Thomas D, Tsolakis AV, Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Fraenkel M, Alexandraki K, Sougioultzis S, Gross DJ, Kaltsas G. Long-term follow-up of a large series of patients with type 1 gastric carcinoid tumors: data from a multicenter study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;168:185-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Kaltsas G, Gur C, Gal E, Thomas D, Fichman S, Alexandraki K, Barak D, Glaser B, Shimon I. Long-acting somatostatin analogues are an effective treatment for type 1 gastric carcinoid tumours. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159:475-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Campana D, Nori F, Pezzilli R, Piscitelli L, Santini D, Brocchi E, Corinaldesi R, Tomassetti P. Gastric endocrine tumors type I: treatment with long-acting somatostatin analogs. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:337-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Jianu CS, Fossmark R, Syversen U, Hauso Ø, Fykse V, Waldum HL. Five-year follow-up of patients treated for 1 year with octreotide long-acting release for enterochromaffin-like cell carcinoids. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:456-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Fossmark R, Sørdal Ø, Jianu CS, Qvigstad G, Nordrum IS, Boyce M, Waldum HL. Treatment of gastric carcinoids type 1 with the gastrin receptor antagonist netazepide (YF476) results in regression of tumours and normalisation of serum chromogranin A. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:1067-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Sato Y, Imamura H, Kaizaki Y, Koizumi W, Ishido K, Kurahara K, Suzuki H, Fujisaki J, Hirakawa K, Hosokawa O. Management and clinical outcomes of type I gastric carcinoid patients: retrospective, multicenter study in Japan. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:377-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Hosokawa O, Kaizaki Y, Hattori M, Douden K, Hayashi H, Morishita M, Ohta K. Long-term follow up of patients with multiple gastric carcinoids associated with type A gastritis. Gastric Cancer. 2005;8:42-46. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Kim BS, Oh ST, Yook JH, Kim KC, Kim MG, Jeong JW, Kim BS. Typical carcinoids and neuroendocrine carcinomas of the stomach: differing clinical courses and prognoses. Am J Surg. 2010;200:328-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | La Rosa S, Inzani F, Vanoli A, Klersy C, Dainese L, Rindi G, Capella C, Bordi C, Solcia E. Histologic characterization and improved prognostic evaluation of 209 gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:1373-1384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 69. | Schindl M, Kaserer K, Niederle B. Treatment of gastric neuroendocrine tumors: the necessity of a type-adapted treatment. Arch Surg. 2001;136:49-54. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Gough DB, Thompson GB, Crotty TB, Donohue JH, Kvols LK, Carney JA, Grant CS, Nagorney DM. Diverse clinical and pathologic features of gastric carcinoid and the relevance of hypergastrinemia. World J Surg. 1994;18:473-479; discussion 479-480. [PubMed] |

| 71. | Merola E, Sbrozzi-Vanni A, Panzuto F, D’Ambra G, Di Giulio E, Pilozzi E, Capurso G, Lahner E, Bordi C, Annibale B. Type I gastric carcinoids: a prospective study on endoscopic management and recurrence rate. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:207-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Vannella L, Sbrozzi-Vanni A, Lahner E, Bordi C, Pilozzi E, Corleto VD, Osborn JF, Delle Fave G, Annibale B. Development of type I gastric carcinoid in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1361-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Uygun A, Kadayifci A, Polat Z, Yilmaz K, Gunal A, Demir H, Bagci S. Long-term results of endoscopic resection for type I gastric neuroendocrine tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:71-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Rappel S, Altendorf-Hofmann A, Stolte M. Prognosis of gastric carcinoid tumours. Digestion. 1995;56:455-462. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Saund MS, Al Natour RH, Sharma AM, Huang Q, Boosalis VA, Gold JS. Tumor size and depth predict rate of lymph node metastasis and utilization of lymph node sampling in surgically managed gastric carcinoids. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2826-2832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Thomas D, Strosberg JR, Pape UF, Felder S, Tsolakis AV, Alexandraki KI, Fraenkel M, Saiegh L, Reissman P. Metastatic type 1 gastric carcinoid: a real threat or just a myth? World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8687-8695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |