Published online Nov 25, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i17.1250

Peer-review started: June 15, 2015

First decision: July 10, 2015

Revised: August 24, 2015

Accepted: September 25, 2015

Article in press: September 28, 2015

Published online: November 25, 2015

Processing time: 163 Days and 23.5 Hours

AIM: To investigate the feasibility of cold snare polypectomy (CSP) in Japan.

METHODS: The outcomes of 234 non-pedunculated polyps smaller than 10 mm in 61 patients who underwent CSP in a Japanese referral center were retrospectively analyzed. The cold snare polypectomies were performed by nine endoscopists with no prior experience in CSP using an electrosurgical snare without electrocautery.

RESULTS: CSPs were completed for 232 of the 234 polyps. Two (0.9%) polyps could not be removed without electrocautery. Immediate postpolypectomy bleeding requiring endoscopic hemostasis occurred in eight lesions (3.4%; 95%CI: 1.1%-5.8%), but all were easily managed. The incidence of immediate bleeding after CSP for small polyps (6-9 mm) was significantly higher than that of diminutive polyps (≤ 5 mm; 15% vs 1%, respectively). Three (5%) patients complained of minor bleeding after the procedure but required no intervention. The incidence of delayed bleeding requiring endoscopic intervention was 0.0% (95%CI: 0.0%-1.7%). In total, 12% of the resected lesions could not be retrieved for pathological examination. Tumor involvement in the lateral margin could not be histologically assessed in 70 (40%) lesions.

CONCLUSION: CSP is feasible in Japan. However, immediate bleeding, retrieval failure and uncertain assessment of the lateral tumor margin should not be underestimated. Careful endoscopic diagnosis before and evaluation of the tumor residue after CSP are recommended when implementing CSP in Japan.

Core tip: Cold snare polypectomy (CSP) was completed for 232 of the 234 polyps. Immediate postpolypectomy bleeding requiring endoscopic hemostasis occurred in eight lesions (3.4%), but all were easily managed. The incidence of immediate bleeding after CSP for small polyps (6-9 mm) was significantly higher than that for diminutive polyps (≤ 5 mm; 15% vs 1%, respectively). Three (5%) patients complained of minor bleeding after the procedure but required no intervention. In total, 12% of the resected lesions could not be retrieved for pathological examination. Tumor involvement in the lateral margin could not be histologically assessed in 70 (40%) lesions.

- Citation: Takeuchi Y, Yamashina T, Matsuura N, Ito T, Fujii M, Nagai K, Matsui F, Akasaka T, Hanaoka N, Higashino K, Iishi H, Ishihara R, Thorlacius H, Uedo N. Feasibility of cold snare polypectomy in Japan: A pilot study. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(17): 1250-1256

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i17/1250.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i17.1250

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common causes of cancer-related death worldwide[1]. The adenoma-carcinoma sequence is thought to be the main route of colorectal cancer development[2], and the removal of colorectal adenomas is known to reduce the risk of subsequent colorectal cancer development and colorectal cancer death[3,4]. Endoscopic removal of all detected adenomas during colonoscopy screening is the standard strategy for the prevention of colorectal cancer, although more than 90% of the polyps are less than 10 mm in size, and most will never develop into cancer during the lifetime of the patient[5]. However, in this context, it is important to note that endoscopic resection is associated with potential complications that include bleeding and perforation[6-8]. Thus, endoscopists should always consider the most likely natural history of the lesion and balance those considerations against the risks associated with endoscopic resection[5]. Indeed, Japanese guidelines do not recommend the removal of diminutive (≤ 5 mm) colorectal polyps[9], and most Japanese endoscopists follow up diminutive colorectal polyps that are not endoscopically removed based on their experience[10].

Several techniques are available for the removal of diminutive or small (6-9 mm) (subcentimetric) polyps, although the optimal method remains unclear, and the method selection is often based on expert opinion. One approach that is used in Western countries for the removal of subcentimetric polyps is cold polypectomy, i.e., removal without electrocautery. This approach seems to minimize the risks of complications when removing subcentimetric lesions[11]. Two different cold polypectomy techniques are available. Cold forceps polypectomy (CFP) is a simple and easy procedure using endoscopic forceps without electrocautery[12]. The second technique is cold snare polypectomy (CSP), which uses snare resection without electrocautery and has been reported to be a safe method for the removal of subcentimetric polyps[13]. Although CSP appears to be a promising procedure for endoscopic removal of subcentimetric colorectal polyps, CSP is not yet widely used in Japan because of the lack of sufficient data about this procedure. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to examine the feasibility of the use of CSP in a Japanese center.

This retrospective study was performed at the endoscopy unit of the Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases. The study protocol was approved by the center’s local ethics committee. Patients with colorectal polyps larger than 5 mm who were recommended to undergo polypectomy and all polyps detected during screening colonoscopies were included in the study. All consecutive patients who underwent colorectal CSP for a subcentimetric polyp between November 2012 and March 2013 were included in a prospectively maintained database. CSP was not performed in patients who were undergoing anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy. Additionally, CSP was not performed for lesions with suspected intramucosal or invasive carcinomas based on endoscopic assessments. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients upon inclusion.

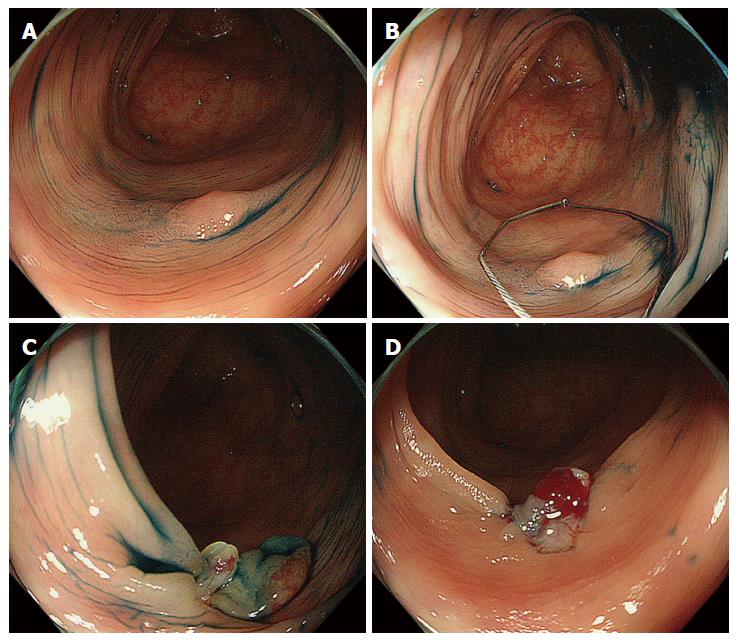

All procedures were performed by nine experienced colonoscopists who had each conducted more than 100 colorectal polypectomies. None of the colonoscopists had performed CSP prior to this trial. A standard type colonoscope (EVIS CF-240I or CF-260DI; Olympus Medical Systems, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) or a high-definition magnifying colonoscope (CF-FH260AZI or CF-H260AZI; Olympus) with a light source (EVIS CLV-260SL; Olympus) and video processor (EVIS LUCERA CV-260SL; Olympus) were used for all patients. A transparent hood (D-201 series; Olympus) was attached to the tip of the colonoscope[14]. All patients were prepared the day before colonoscopy with a low fiber diet and preparatory medicines. Bowel preparation and sedation were administered as previously described in detail[15]. The colonoscope was first inserted into the cecum using the conventional white light mode. In cases of incomplete total colonoscopy (e.g., stenosis with advanced colorectal cancer, pain or discomfort or difficult insertion caused by looping), any detected lesions were recorded and removed within the range of observation. The location, size, and macroscopic type of all of the lesions were documented according to the Paris classification[16,17]. The size was determined using biopsy forceps with a 2.2-mm outer diameter (Radial Jaw 3; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States) or a 13-mm small hexagonal electrosurgical snare (Captivator; Boston Scientific). Magnifying endoscopy was performed to predict the tumor histology when available. CSP was performed using an electrosurgical snare (Captivator; Boston Scientific) without electrocautery (Figure 1, videos). The polyp was snared including normal surrounding mucosa to maintain a non-neoplastic mucosal margin around the lesion. Blood oozing was usually observed immediately after CSP. In the first 10 cases, we observed the resection sites until the oozing stopped. After these 10 cases, oozing wounds were left behind, and endoscopic hemostasis was only performed when spurting or massive bleeding occurred. If the polyps were unresectable with CSP, electrocautery was used for their removal. The removed lesions were suctioned and retrieved after CSP. The retrieved specimens were immersed in 20% formalin without pinning on a plate and examined using standard hematoxylin and eosin staining. Two experienced histopathologists who were blinded to the endoscopic findings evaluated all of the specimens according to the Japanese classification of colorectal carcinomas[18].

The procedural details were prospectively recorded in a database, and the medical records were thoroughly investigated. The collected data included patient age, gender, polyp location (i.e., cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, or rectum), polyp size, endoscopist (expert or senior resident), morphological type (i.e., protruded/sessile or superficial/elevated), histological diagnosis, incidence of immediate postpolypectomy bleeding requiring endoscopic hemostasis, incidence of delayed bleeding (clinically evident after examination) and any abdominal symptoms. Endoscopic hemostasis was usually performed for delayed postpolpectomy bleeding when patients experienced repetitive bloody bowel discharges or became hemodynamically unstable. The study investigators assessed the symptoms in the outpatient department during follow-up appointments. Because this was a pilot feasibility study, the sample size was not estimated. The results related to non-parametric data are reported as the medians (ranges) and were compared by Wilcoxon test. The incidence (%) was used for the categorical variables, which were compared using the Yates’χ2 test. The data analyses were conducted using the statistical package JMP 10 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

Two-hundred patients underwent colorectal endoscopic resection (including conventional polypectomy, endoscopic mucosal resection, and endoscopic submucosal dissection) between November 2012 and March 2013. CSP was attempted in 61 patients in this study. The baseline data of the participants are shown in Table 1. The median age (range) of the patients was 65 (40-86) years. The patients comprised 44 (72%) men and 17 (28%) women. In total, 234 subcentimetric lesions were detected during colonoscopy screening. The median and maximum numbers of polyps detected per patient were 3 and 16, respectively. Thirteen (21%) patients presented with only one subcentimetric polyp, and 48 (79%) patients presented with at least two subcentimetric lesions. Two hundred five (88%) of the lesions were protruded/sessile (0-Is), and 29 (12%) were superficial/elevated (0-IIa). The median (range) size of the polyps was 4 (1-9) mm. Among these lesions, 186 (80%) were diminutive (≤ 5 mm), and 48 (20%) were small (6-9 mm). One hundred and thirty-six (58%) polyps were located proximal to the splenic flexure, and 98 (42%) were situated distal to the splenic flexure. In total, 79 (34%) CSP procedures were performed by four experts, and 155 (66%) were performed by five senior residents.

| Male/female (%) | 44 (72%)/17 (28%) |

| Median age | 65 |

| (range, yr) | (40-86) |

| Total detected lesion | 234 |

| Median detected lesion per patient (range) | 3 (1-16) |

| Location | |

| Cecum | 19 (8%) |

| Ascending colon | 61 (26%) |

| Transverse colon | 56 (24%) |

| Descending colon | 33 (14%) |

| Sigmoid colon | 52 (22%) |

| Rectum | 13 (6%) |

| Morphology | |

| Protruded, sessile | 205 (88%) |

| Superficial, elevated | 29 (12%) |

| Median detected polyp size | 4 |

| (range, mm) | (1-9) |

| Endoscopist | |

| Expert | 79 (34%) |

| Senior resident | 155 (66%) |

| Histological type | |

| Not retrieved | 28 (12%) |

| Non-neoplastic polyp | 28 (12%) |

| Neoplastic polyp | 176 (76%) |

| Horizontal margin (neoplastic lesion only) | |

| HM 0 | 104 (59%) |

| HM 1 | 2 (1%) |

| HM X | 70 (40%) |

CSP was attempted for 234 subcentimetric polyps in 61 patients. Two (0.9%) polyps could not be resected without electrocautery and were thus removed by conventional polypectomy with electrocautery. One of these was a 2-mm protruded type inflammatory polyp that was located near a scar from a previous polypectomy in the transverse colon. The other polyp was an 8-mm protruded type adenoma located in the rectum. Thus, CSP was completed for 232 polyps in 61 patients. Immediate postpolypectomy bleeding requiring endoscopic hemostasis occurred in eight lesions (3.4%; 95%CI: 1.1%-5.8%). Although no differences were observed in sex, age, location, morphology, endoscopist or histological type between the lesions with and without immediate bleeding, the median lesion size with immediate bleeding was larger than that of the lesions without immediate bleeding (7.5 mm vs 4.0 mm, respectively, P = 0.002), and the incidence of immediate bleeding after CSP was greater for the small than the diminutive polyps (15% vs 1%, respectively, P = 0.001) (Table 2). All eight cases of immediate postpolypectomy bleeding were easily managed by endoscopic clipping alone. All patients who underwent CSP visited our outpatient department 7-35 d (median, 14 d) after the procedures. Three (5%) patients complained of minor bleeding after the procedure that stopped without any intervention. Therefore, the incidence of delayed bleeding requiring endoscopic intervention after CSP without prophylactic clipping was 0.0% (95%CI: 0.0%-1.7%). No other complications, such as perforation or postpolypectomy syndrome, were observed. Twenty-eight (12%) of the 232 lesions could not be retrieved after resection for pathological analysis. The remaining 204 (88%) polyps underwent histopathological assessments that revealed 176 (76%) neoplastic polyps (163 low-grade adenomas, 1 tubulovillous adenoma, 4 high-grade adenomas, 5 sessile serrated adenomas/polyps and three serrated adenomas) and 28 (12%) non-neoplastic lesions. The horizontal margins (HMs) of the neoplastic lesions that were removed by CSP underwent pathological assessments. One hundred four (59%) lesions were classified as HM 0 (i.e., no tumor identified at the lateral margin), 2 (1%) were classified as HM 1 (i.e., tumor identified at the lateral margin), and 70 (40%) were classified as HM X (i.e., tumor involvement at the lateral margin could not be assessed).

| Immediate bleeding(n = 8) | Non-immediate bleeding(n = 224) | P-value | |

| Male/female | 8/0 | 146/78 | 0.10a |

| Median age | 64.5 | 68 | 0.27b |

| (range, years) | (50-76) | (40-86) | |

| Location | 0.40a | ||

| Proximal to splenic flexure | 3 (38%) | 132 (59%) | |

| Distal from splenic flexure | 5 (62%) | 92 (41%) | |

| Morphology | 0.59a | ||

| Protruded, sessile (0-Is or Isp) | 7 (88%) | 196 (88%) | |

| Flat, elevated (0-IIa) | 1 (12%) | 28 (12%) | |

| Median size | 7.5 (3-9) | 4 (1-9) | 0.002b |

| (range, mm) | |||

| ≤ 5 mm (%) | 2 (22%) | 183 (82%) | 0.001a |

| > 6 mm (%) | 6 (78%) | 41 (18%) | |

| Endoscopist | 0.54a | ||

| Expert | 4 (50%) | 74 (33%) | |

| Senior resident | 4 (50%) | 150 (67%) | |

| Histological type | |||

| Not retrieved | 0 (0%) | 28 (12.5%) | |

| Non-neoplastic polyp | 0 (0%) | 28 (12.5%) | 0.53a |

| Neoplastic polyp | 8 (100%) | 168 (75%) |

Although CSP has been reported to minimize the risk of complications when removing subcentimetric polyps in Western countries[19,20], this technique has not yet been widely implemented in Japan. The present study represents one of the largest patient samples regarding CSP from any Japanese institution to date[21-23]. Our results indicate that CSP is a safe and effective method for resecting small colorectal lesions and suggest that CSP is also a feasible method for the removal of subcentimetric polyps in Japan.

Herein, we observed that the incidence of immediate bleeding requiring endoscopic treatment after CSP was 3.4%, which is somewhat higher than that reported in the prospective multicenter study conducted by Repici et al[11] (1.8%). However, only 37% of the procedures were CSPs, and the others were CFPs in the study by Repici et al[11]. Thus, the incidence of immediate bleeding after CSP might be different from that after CFP. In this context, it should also be mentioned that none of participating endoscopists herein had performed CSP prior to this study, and some of them might have been cautious about oozing that occurred after CSP and unnecessarily used endoscopic clips. Regardless, all cases of immediate CSP-associated bleeding were easily managed endoscopically. Caution might be required when adopting CSP, especially for small (6-9 mm) polyps because these polyps exhibited a higher incidence of immediate bleeding compared to the diminutive (≤ 5 mm) polyps. We observed no CSP cases involving delayed bleeding, perforation or postpolypectomy syndrome that required treatment in this trial, which is perhaps one of the greatest advantages of CSP.

Many Japanese patients who undergo polypectomy are currently hospitalized for a few days, and the number of hospitals that can perform polypectomy is insufficient to treat all of the patients with colorectal polyps. Considering this limited access to polypectomy in Japan and the fact that more than 90% of polyps are subcentimetric, it is possible that the implementation of CSP could increase the availability of a safe and easy procedure for the removal of subcentimetric polyps in outpatients, which could not only the decrease medical expenses associated with hospitalization but also shorten the waiting time for polyp removal in large groups of patients in Japan. Nonetheless, it should be noted that minor bleeding (that did not require endoscopic hemostasis) was observed in 3 patients (5%) after CSP. Although we rarely experience such minor bleeding after conventional polypectomy with electrocautery, this information is important when adopting CSP in daily practice.

Notably, we observed that CSP was associated with a retrieval failure of 12%. Deenadayalu and Rex[24] reported no cases of retrieval failure after CSP in their study, whereas Komeda et al[25] reported a retrieval failure of 19% after CSP. The relatively higher incidence of retrieval failure associated with CSP might be an issue of concern for endoscopists who do not currently apply CSP in clinical practice. However, because the indication for CSP is limited to subcentimetric polyps, which have low risks for invasive carcinomas, this aspect is perhaps not a major concern. Additionally, the “resect and discard” policy, which omits formal pathological examination, is now regarded as a promising strategy for decreasing the cost and labor associated with screening and surveillance colonoscopy[26,27]. Therefore, retrieval failure will not be a major obstacle for the generalization of CSP in the future especially if a “resect and discard” strategy is adopted. Of course, careful endoscopic assessment before CSP is essential to avoid removing and discarding invasive carcinomas. Magnifying narrow-band imaging may be a promising tool to secure the safety of both CSP (i.e., by preventing the removal of subcentimetric invasive carcinomas) and the “resect and discard” strategy because pretreatment assessment using magnifying endoscopy allows for the selection of lesions with advanced histologies[28,29]. Therefore, we believe that the combination of CSP and the “resect and discard” strategy using magnifying narrow-band imaging could provide a more efficient (i.e., simple, safe, and cost-effective) strategy for screening and surveillance colonoscopy.

Assessment of the HMs of tumor specimens that have been resected by CSP is also a potential concern for endoscopists who are skeptical about CSP because we cannot expect the thermal burn effect to eradicate the neoplastic tissue around the electrosurgical snare during CSP. The incidence of HM 1 was only 1.1% in our trial, but the incidence of HM X was 40%. The main indication for CSP is subcentimetric polyps, and for such lesions, doctors do not usually pay attention to HM X statuses because they expect the thermal burn effect to occur and routinely confirm the absence of tumor residue via observations of the surrounding mucosa. Although Lee et al[30] reported a significantly higher rate of histologic eradication with CSP than with CFP in their prospective randomized controlled trial, the non-inferiority of CSP for tumor residues compared with conventional polypectomy warrants further investigation of the efficacy of CSP. In the meantime, although it is important to pay attention to the presence of tumor residue after CSP, care must be taken to remove the surrounding non-neoplastic mucosa as well as the targeted lesion when implementing CSP. Moreover, careful observation of the surrounding mucosa after CSP using magnifying endoscopy or chromoendoscopy, the washing out of minor bleeding after CSP, and strict surveillance colonoscopy are recommended until the evidence for tumor residue after CSP is considered to be adequate.

This was only a pilot study and therefore has some limitations. First, although the number of CSP procedures was larger than those of previous reports, the small sample size remains still a major limitation of this trial. A large-scale prospective study investigating the actual incidence of delayed bleeding after CSP should be conducted in the future. Second, we used a conventional electrosurgical snare in this trial because the snare developed for CSP was not available during the study period. The use of this snare may have affected the rates of removal failures or insufficient assessments of the HMs of the resected specimens. Finally, although the CSPs in this study were performed by nine endoscopists with no prior experience in CSP, different results might have been obtained if the endoscopists had experienced at least 20-30 CSPs. Specifically, the 70 (40%) HM X lesions should be carefully assessed.

In conclusion, we found that CSP is effective for removal subcentimetric polyps in the colon and rectum. CSP was safe and resulted in no cases of delayed bleeding or perforation and a 3.4% incidence of manageable immediate bleeding. Attention should be given to the potential risk of bleeding immediately after CSP, particularly for small (6-9 mm), lesions as well as to careful endoscopic diagnosis before CSP and the evaluation of tumor residue after CSP. Other areas of concern when implementing CSP might be retrieval failure and incomplete HM assessment. Nonetheless, we conclude that CSP for subcentimetric colorectal lesions is also a feasible procedure for implementation in Japan.

Although cold snare polypectomy (CSP) using snare resection without electrocautery has been reported to be a safe method for the removal of subcentimetric polyps, CSP is not currently widely used in Japan.

CSP is a promising procedure, but there are no detailed data about immediate bleeding or the horizontal margins of the histological specimens from Japanese institutions.

The incidence of immediate bleeding after CSP for small polyps (6-9 mm) was significantly higher than that for diminutive polyps (≤ 5 mm). Histopathological diagnoses can be often insufficient because 12% of the resected lesions could not be retrieved for pathological examination, and tumor involvement in the lateral margin could not be histologically assessed in 70 (40%) lesions.

The authors need to be cautious in the performance of CSP for small (6-9 mm) polyps due to concerns about immediate bleeding and histopathological assessment.

Cold forceps polypectomy is a simple procedure that uses endoscopic forceps without electrocautery. CSP is a procedure that uses snare resection without electrocautery.

This is an important manuscript.

P- Reviewer: El-Tawil AM, Horiuchi A, Ikematsu H, Sieg A S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:283-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Morson B. President’s address. The polyp-cancer sequence in the large bowel. Proc R Soc Med. 1974;67:451-457. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O’Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977-1981. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, Shi W, Bond JH, Schapiro M, Panish JF. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1952] [Cited by in RCA: 2286] [Article Influence: 175.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | British Society of Gastroenterology. Colonoscopic polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection: A practical guide. Available from: http://www.bsg.org.uk/clinical-guidance/endoscopy/colonoscopic-polypectomy-and-endoscopic-mucosal-resection-a-practical-guide.html. |

| 6. | Tajiri H, Kitano S. Complications associated with endoscopic mucosal resection: definition of bleeding that can be viewed accidental. Dig Endosc. 2004;16:S134-136. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Waye JD. Management of complications of colonoscopic polypectomy. Gastroenterologist. 1993;1:158-164. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Oka S, Tanaka S, Kanao H, Ishikawa H, Watanabe T, Igarashi M, Saito Y, Ikematsu H, Kobayashi K, Inoue Y. Current status in the occurrence of postoperative bleeding, perforation and residual/local recurrence during colonoscopic treatment in Japan. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:376-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Japanese Society of Gastroenterology. Practical guideline for colorectal polyp 2014. Nankodo, Tokyo, Japan, 2014. . |

| 10. | Matsuda T, Kawano H, Hisabe T, Ikematsu H, Kobayashi N, Mizuno K, Oka S, Takeuchi Y, Tamai N, Uraoka T. Current status and future perspectives of endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of diminutive colorectal polyps. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 2:104-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Repici A, Hassan C, Vitetta E, Ferrara E, Manes G, Gullotti G, Princiotta A, Dulbecco P, Gaffuri N, Bettoni E. Safety of cold polypectomy for & lt; 10mm polyps at colonoscopy: a prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:27-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Uraoka T, Ramberan H, Matsuda T, Fujii T, Yahagi N. Cold polypectomy techniques for diminutive polyps in the colorectum. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 2:98-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Tappero G, Gaia E, De Giuli P, Martini S, Gubetta L, Emanuelli G. Cold snare excision of small colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:310-313. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Takeuchi Y, Inoue T, Hanaoka N, Chatani R, Uedo N. Surveillance colonoscopy using a transparent hood and image-enhanced endoscopy. Dig Endosc. 2010;22 Suppl 1:S47-S53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Takeuchi Y, Inoue T, Hanaoka N, Higashino K, Iishi H, Chatani R, Hanafusa M, Kizu T, Ishihara R, Tatsuta M. Autofluorescence imaging with a transparent hood for detection of colorectal neoplasms: a prospective, randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1006-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Participants in the Paris Workshop. The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Dixon MF. Gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia: Vienna revisited. Gut. 2002;51:130-131. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma, Second English Edition. Kanehara & CO., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, 2009. . |

| 19. | Singh N, Harrison M, Rex DK. A survey of colonoscopic polypectomy practices among clinical gastroenterologists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:414-418. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Hewett DG, Rex DK. Colonoscopy and diminutive polyps: hot or cold biopsy or snare? Do I send to pathology? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:102-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ichise Y, Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y, Tanaka N. Prospective randomized comparison of cold snare polypectomy and conventional polypectomy for small colorectal polyps. Digestion. 2011;84:78-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y, Kajiyama M, Tanaka N, Sano K, Graham DY. Removal of small colorectal polyps in anticoagulated patients: a prospective randomized comparison of cold snare and conventional polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Horiuchi A, Hosoi K, Kajiyama M, Tanaka N, Sano K, Graham DY. Prospective, randomized comparison of 2 methods of cold snare polypectomy for small colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:686-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Deenadayalu VP, Rex DK. Colon polyp retrieval after cold snaring. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:253-256. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Komeda Y, Suzuki N, Sarah M, Thomas-Gibson S, Vance M, Fraser C, Patel K, Saunders BP. Factors associated with failed polyp retrieval at screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:395-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ignjatovic A, East JE, Suzuki N, Vance M, Guenther T, Saunders BP. Optical diagnosis of small colorectal polyps at routine colonoscopy (Detect InSpect ChAracterise Resect and Discard; DISCARD trial): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1171-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hassan C, Pickhardt PJ, Rex DK. A resect and discard strategy would improve cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:865-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Takeuchi Y, Hanafusa M, Kanzaki H, Ohta T, Hanaoka N. Proposal of a new ‘resect and discard’ strategy using magnifying narrow band imaging: pilot study of diagnostic accuracy. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 2:90-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Takeuchi Y, Hanafusa M, Kanzaki H, Ohta T, Hanaoka N, Yamamoto S, Higashino K, Tomita Y, Uedo N, Ishihara R. An alternative option for "resect and discard" strategy, using magnifying narrow-band imaging: a prospective "proof-of-principle" study. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1017-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lee CK, Shim JJ, Jang JY. Cold snare polypectomy vs. Cold forceps polypectomy using double-biopsy technique for removal of diminutive colorectal polyps: a prospective randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1593-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |