Published online Aug 16, 2013. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i8.417

Revised: May 31, 2013

Accepted: June 28, 2013

Published online: August 16, 2013

Processing time: 150 Days and 10.1 Hours

Dieulafoy’s lesion (DL) is a rare but important cause of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding that may be overlooked during diagnostic endoscopy. Mortality rates are similar to those of other causes for gastrointestinal bleeding. Diagnosis by upper endoscopy is the modality of choice during acute bleeding. In the absence of active bleeding, the lesion resembles a raised nipple or visible vessel. There are no guidelines regarding effective selective therapy for DL, when diagnosed, endoscopist experience is the major determinant of the treatment strategy. Following our strategy, an expert endoscopist with a skilled assistant should have a high rate of successful DL diagnosis when an obscured gastrointestinal lesion is suspected. Cyanoacryltes compounds have been used successfully in management of Gastric varices and DLs. To our knowledge, there have been no previous reports regarding use of isoamyl-2-cyanoacrylate (AMCRYLATE®; Concord Drugs Ltd., Hyderabad, India) as an effective therapy for gastric DL without serious complications. In our case study, Isoamyl-2-cyanoacrylate (AMCRYLATE®) was effective and safe for treating DL. Surgical wedge resection of the lesion should be considered as a therapeutic option if endoscopic therapy fails.

Core tip: The etiology of Dieulafoy’s lesion (DL) is unknown. The hemorrhage is often torrential and life threatening. Diagnosis by upper endoscopy is the modality of choice during acute bleeding. In the absence of active bleeding, the lesion resembles a raised nipple or visible vessel. There are no guidelines regarding effective selective therapy for DL. When diagnosed, endoscopist experience is the major determinant of the treatment strategy. To our knowledge, there have been no previous reports regarding use of isoamyl-2-cyanoacrylate (AMCRYLATE®; Concord Drugs Ltd., Hyderabad, India) as an effective therapy for gastric DLs without serious complications.

- Citation: Elrazek AEMAA, Yoko N, Hiroki M, Afify M, Asar M, Ismael B, Salah M. Endoscopic management of Dieulafoy’s lesion using Isoamyl-2-cyanoacrylate. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 5(8): 417-419

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v5/i8/417.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i8.417

Dieulafoy’s lesion (DL) is an important cause of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding that may be overlooked during diagnostic endoscopy or even laparotomy. The hemorrhage is often torrential and life threatening. The French pathologist Dieulafoy, who described three cases, discovered the lesion in 1889, although the first case was actually reported by Gallard in 1884. DLs can occur in any part of the gastrointestinal tract with a tendency toward the lower end of the esophagus, cardia, lesser curvature of the stomach, and caecum[1].

The etiology of DL is unknown. Patients who bleed from DLs are typically males with comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes or alcohol abuse. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is also common among patients with bleeding, although many patients have no triggering events. DLs can appear any time between 20 mo and 92 years of age[2,3].

Diagnosis by upper endoscopy is the modality of choice during acute bleeding. In the absence of active bleeding, the lesion resembles a raised nipple or visible vessel. In massive bleeding, active arterial pumping can be visualized in an area without an associated ulcer or mass lesion, although the aberrant vessel is often not seen. Endoscopic ultrasonography is useful for confirmation of the diagnosis[4].

There are no guidelines regarding effective selective therapy for DL. When diagnosed, endoscopist experience is the major determinant of the treatment strategy. Many therapeutic approaches exist, including endoscopic hemostasis with a combination of epinephrine followed by bipolar probe coagulation; heater probe thermal coagulation; hemoclip placement; band ligation; argon plasma coagulation; arterial angiographic embolization; endoscopic sclerotherapy using ethanolamine oleate, polidocanol, or N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate; and surgical wedge resection of the lesion, which is now rarely performed due to the availability of more advanced endoscopic technologies and increased operator experience[5].

In the 1940s, various surgical cyanoacrylate adhesives were developed; these are a series of homologous alkyl-cyanoacrylate compounds. These compounds polymerize on contact with common substances, such as blood and water, at room temperature without requiring a solvent or catalyst. Adhesive glue is particularly useful for day surgeries, e.g., circumcision. Cyanoacrylate is superior to sutures and its clinical use is becoming increasingly common due to its ease of application, decreased scarring, decreased pain, and superior cosmetic results with no discomfort, as can occur due to sutures snagging clothing and/or the dressing[6-8]. Many authors have reported the disadvantages of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate as a treatment of choice for DL because of serious complications of extravasation, rebleeding due to massive ulceration, and even gastric perforation[9]. Radiographically evident Pulmonary Embolism was reported after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) for gastric variceal bleeding using N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate[10].

To our knowledge, there have been no previous reports regarding use of isoamyl-2-cyanoacrylate (AMCRYLATE®; Concord Drugs Ltd., Hyderabad, India) as an effective therapy for gastric DLs without serious complications.

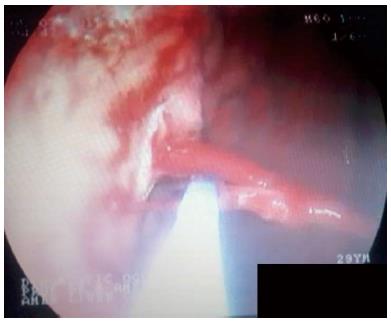

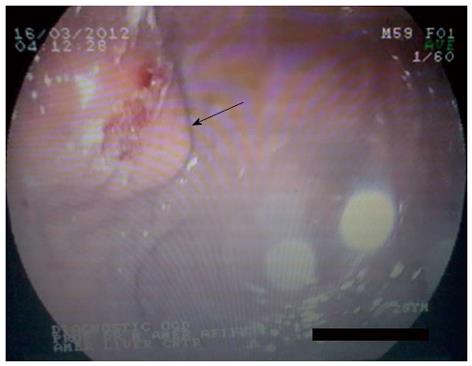

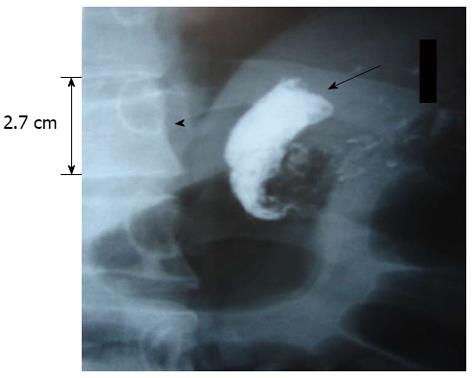

A 29-year-old male patient was admitted with hematemesis with no history of the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, paracetamol, caffeine or alcohol abuse. There was no family history of bleeding disorders. The patient denied having taken medications for any illness, and no abnormalities were detected on ultrasound examination. Upper endoscopy revealed no masses, ulcers, varices, or any lesions. Six hours later, the patient developed massive hematemesis following the administration of 500 mL of packed red blood cells. Upper endoscopy was repeated, but no lesion was seen. The patient was administered hemostatic medications. One day after discharge, a massive attack of hematemesis recurred 48 h after the previous attack. The patient was transferred to our clinic, where upper endoscopy was repeated for the third time. A gastric wash was performed and an endoscopy expert was called. Upper endoscopy revealed a nipple-like protrusion on the greater curvature just 5 cm below the cardia. Touching the lesion with the blind, smooth end of a probe led to massive hemorrhage (Figure 1). The gastric wash was repeated with the administration of another 500 mL of packed red blood cells. Endoscopic sclerotherapy was performed using 1 mL of isoamyl-2-cyanoacrylate (AMCRYLATE®) in 1 mL of Lipidol in a 1:1 ratio. The bleeding was stopped (Figures 2 and 3). Post-endoscopic erect abdominal X-ray showed no extravasation. The caliber of the Dieulafoy’s arteriole was relatively large; it opened directly into the stomach without branching, making it more than ten times larger than other gastric capillaries (Figure 4). Follow-up 3 mo later showed no complications due to the therapy and no extravasations, ulcerations or any other hemostatic disorders.

The use of isoamyl-2-cyanoacrylate (AMCRYLATE®) could be an effective treatment for gastric DLs because the viscosity and adhesive problems that can occur with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate are significantly reduced by use of isoamyl-2-cyanoacrylate (AMCRYLATE®). We expect fewer complications with almost identical results. Another advantage is that AMCRYLATE® is significantly more cost-effective than N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate, especially when large amounts are required.

According to our experience, it is convenient to use isoamyl-2-cyanoacrylate as effective endoscopic management for gastric varices. The use of isoamyl-2-cyanoacrylate significantly reduced post endoscopic ulceration compared to N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate.

In summary, DL is an infrequent but severe and obscure cause of gastrointestinal hemorrhage, which occurs predominantly in males. Repeated endoscopy is often required to determine the diagnosis. An expert endoscopist with a skilled assistant should have a high rate of successful diagnosis of DL. Thus, use of isoamyl-2-cyanoacrylate (AMCRYLATE®) seems effective and safe for treatment of gastric DLs. Surgical wedge resection should be reserved for difficult-to-control bleeding. Death may occur if bleeding is not controlled.

P- Reviewer Islam RS S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Pollack R, Lipsky H, Goldberg RI. Duodenal Dieulafoy’s lesion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:820-822. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Lara LF, Sreenarasimhaiah J, Tang SJ, Afonso BB, Rockey DC. Dieulafoy lesions of the GI tract: localization and therapeutic outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3436-3441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lee YT, Walmsley RS, Leong RW, Sung JJ. Dieulafoy’s lesion. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:236-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Squillace SJ, Johnson DA, Sanowski RA. The endosonographic appearance of a Dieulafoy’s lesion. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:276-277. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Liu D, Lu F, Ou D, Zhou Y, Huo J, Zhou Z. [Endoscopic band ligation versus endoscopic hemoclip placement for bleeding due to Dieulafoy lesions in the upper gastrointestinal tract]. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2009;34:905-909. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Quinn J, Wells G, Sutcliffe T, Jarmuske M, Maw J, Stiell I, Johns P. A randomized trial comparing octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive and sutures in the management of lacerations. JAMA. 1997;277:1527-1530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Aubert A, Hammel P, Zappa M, Kianmanesh R, O’Toole D, Lévy P, Ruszniewski P. [Gastric perforation by histoacryl extravasation as a complication of endoscopic sclerotherapy for bleeding Dieulafoy ulcer]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:155-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mertz PM, Davis SC, Cazzaniga AL, Drosou A, Eaglstein WH. Barrier and antibacterial properties of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate-derived wound treatment films. J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee GH, Kim JH, Lee KJ, Yoo BM, Hahm KB, Cho SW, Park YS, Moon YS. Life-threatening intraabdominal arterial embolization after histoacryl injection for bleeding gastric ulcer. Endoscopy. 2000;32:422-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hwang SS, Kim HH, Park SH, Kim SE, Jung JI, Ahn BY, Kim SH, Chung SK, Park YH, Choi KH. N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate pulmonary embolism after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for gastric variceal bleeding. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25:16-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |