INTRODUCTION

Strictures are a common complication of Crohn’s disease (CD), occurring in 1/3 of patients after 10 years of disease. They occur most frequently in the ileocecal region and rectum and at anastomotic sites where the disease is likely to recur[1]. Medical therapy has not been shown to be effective in the treatment of fibrotic strictures, and its role in preventing stricture formation has been disappointing[2]. As disease recurrence is common, endoscopic methods, such as balloon dilation or stenting for refractory strictures, have been advocated to decrease surgery.

Biodegradable stents were originally developed to treat refractory benign esophageal strictures but are a promising therapeutic option for intestinal strictures because they do not require removal and may be able to overcome some of the drawbacks of self-expandable metallic stents (SEMS). We report our experience with the off-label use of a biodegradable esophageal polydioxanone stent in the management of a colonic stricture complicating CD.

CASE REPORT

A 33-year-old female with a history of CD was admitted to the hospital in February 2011 with abdominal cramps, constipation and air-fluid levels in the small and large bowel on X-ray. The CD diagnosis had been established at age 16 years. The disease involved the terminal ileum, colon and perianal region and presented with an inflammatory behavior (A1L3B1p according to the Montreal classification)[3,4]. She was initially treated with oral corticosteroids and started on azathioprine, but in 2001 infliximab was added for persistent symptoms. The patient experienced some flares over the years until 2009, when she achieved sustained clinical and endoscopic remission while on azathioprine at 3 mg/kg per day and infliximab at 5 mg/kg every 4 wk.

The laboratory results were unremarkable with no signs of systemic inflammation. A computed tomography scan revealed concentric wall thickening over 6 cm lengths in the sigmoid colon with narrowing of the lumen and prestenotic dilation but no regional lymphadenopathy. The bowel obstruction resolved with nasogastric tube suction and intravenous fluids. Colonoscopy confirmed the existence of a distal sigmoid stricture that precluded the passage of the conventional colonoscope (CF-Q160AL, Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan). A slim colonoscope (PCF-Q180AL Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan) was used to reach the terminal ileum. There were no endoscopic signs of inflammation. The colon was shortened and showed extensive scarring and some inflammatory polyps; the ileal mucosa appeared to be normal. Dysplasia and malignancy were excluded by several biopsies of the entire length of the stricture.

A short cycle of oral corticosteroids was completed, but the stricture was refractory to medical therapy, and the patient complained of abdominal pain and experienced a new episode of bowel obstruction in September 2011. After having discussed the therapeutic options in a gastrointestinal multidisciplinary team meeting, we decided to place a SX-ELLA BD biodegradable esophageal stent (ELLA-CS, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic; Figure 1) with a trunk diameter of 20 mm flaring to 25 mm at both ends and a length of 100 mm. The local ethics committee approved the procedure, and informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Figure 1 SX-ELLA biodegradable biodegradable esophageal stent.

The stent is flared at both ends to reduce the risk of migration and is fitted with radiopaque markers at the midpoint and at the ends to enable precise stent positioning under fluoroscopic control. Because of reduced long-term elasticity, the stent is supplied separate from the delivery system and needs to be manually loaded just before the implantation procedure (see manufacturer’s “Instructions for Use”).

The procedure was performed under conscious sedation (intravenous midazolam) via an anal approach with the patient lying on her left side. Both margins of the stricture were marked by using intramucosal lipiodol injection. The stent was loaded into its dedicated 28 French delivery system and implanted under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance over a stiff 0.035-inch guidewire with a soft tip (Jagwire, Boston Scientific, Natick, United States) that was previously introduced through the stricture. Pre-dilation was not performed. An adequate expansion of the stent occurred immediately after its insertion (Figures 2 and 3). Significant stent shortening occurred upon deployment, and a water-soluble contrast (Xenetix 350, Guerbet Laboratories, Roissy, France) was injected at the end of the procedure to confirm proper stent position and luminal patency. There were no immediate or delayed procedure-related complications, namely perforation, pain, hemorrhage or stent migration. The stent insertion provided rapid clinical improvement and symptom relief, and the patient was discharged within 24 h.

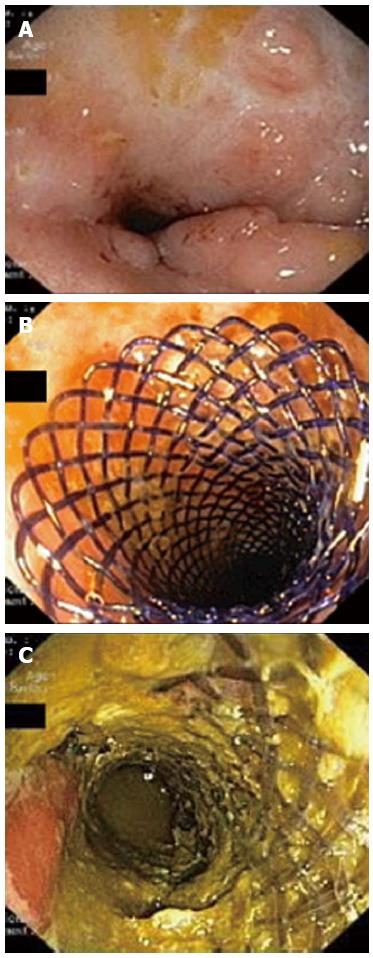

Figure 2 Endoscopic images.

A: Stricture of the distal sigmoid colon before stent insertion. The surrounding mucosa show no signs of active inflammation and few inflammatory polyps; B: Biodegradable stent deployed in the stricture at the end of the procedure; C: Endoscopic view 1 mo after the stent placement. The stent fibers present a translucent appearance and partial fragmentation.

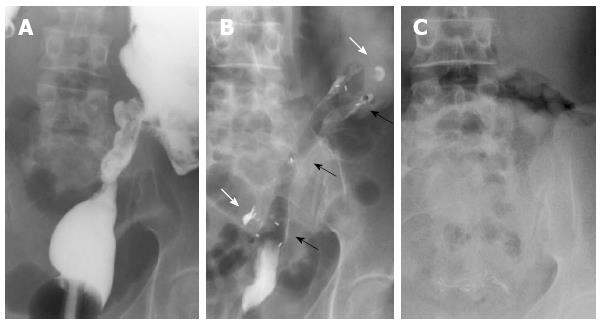

Figure 3 Radiographic images.

A: Stricture of the distal sigmoid colon outlined by luminal filling with barium using a rectal catheter (supine position); B: Biodegradable stent in situ immediately after insertion (supine position). The stent is radiolucent, but the radiopaque markers at the midpoint and at the ends are visible (black arrows). The margins of the stricture are marked with lipiodol (white arrows); C: Disappearance of radiopaque markers at 4 mo confirming complete stent degradation (erect position).

A clinical and radiographic follow-up was performed one week after the stent insertion and again one month later, with no evidence of stent migration. At that time, an endoscopy follow-up was also performed to monitor the stent patency and degradation. There was no significant mucosal hyperplasic reaction and no resistance to the progression of the conventional scope through the stent (Figure 2). Complete stent degradation was confirmed on a plain abdominal X-ray 4 mo after the insertion (Figure 3). There was no recurrence of the obstructive symptoms during a 16-mo follow-up.

DISCUSSION

We report a case of a patient with a long-standing CD who developed a symptomatic fibrotic stricture of the colon despite optimized medical treatment with infliximab and azathioprine. Fibrotic strictures in CD patients have been traditionally treated with intestinal resection, which is often extensive and associated with high morbidity rates[5]. Furthermore, disease recurrence is common. Within 4 years, approximately 40% of the patients will need another resection[6,7]. Concerns over short-bowel syndrome caused by multiple resections and large segment resections led to the development of bowel-sparing surgical techniques or strictureplasty, however, within 10 years, up to 50% of these patients will require repeated surgery because of obstruction recurrence[8]. Facing the problems related to repeated surgery, endoscopic methods have been advocated for managing CD strictures. Balloon dilation (with or without steroid injection) is currently the endoscopic treatment of choice. Several uncontrolled observational studies have shown that balloon dilation is a safe and effective alternative to surgery in selected patients. It has and has a technical success rate that ranges from 71% to 90% and a major complications rate of 2% to 3%[9-11]. However, it is generally accepted that strictures greater than 4 cm are not amenable to balloon dilation, and the recurrence rate of obstructive symptoms is as high as 42% with the need for repeated dilations and their associated perforation risk.

Our patient was not a candidate for balloon dilation because of the extent of the stricture, and surgical resection would likely have been extensive because of the scarring colon. Stent placement was thus considered. Compared with balloon dilation, stents determine slower and more sustained stricture dilation, resulting in reduced trauma and subsequent fibrosis. Furthermore, the radial force is maintained for several weeks, allowing remodeling of the stricture and increased long-term luminal patency with a reduced need for repeated dilations. However, data regarding the efficacy and safety of extractable SEMS in the treatment of symptomatic intestinal strictures in CD are limited and conflicting[12-16]. In general, the use of fully covered SEMS in this setting appears to be effective but has been associated with several drawbacks and complications, such as a high rate of spontaneous migrations and the need for removal, and remains controversial. The recently developed biodegradable stents are a promising option because of their longer patency and no need for removal, although radial force is lower compared with nitinol stents.

Biodegradable stents are manufactured from different synthetic polymers that have other well-established biomedical applications, particularly in the fields of sutures, tissue engineering and controlled drug delivery. The polymers are degraded by random hydrolysis of their molecules’ ester bounds, and the degradation products are metabolized via normal metabolic pathways. This process compromises the structure and integrity of the stent filaments and leads to the loss of radial force, fracture of the stent skeleton and disintegration. The radial force of polydioxanone stents is maintained for approximately 6-8 wk following implantation and drops to 50% by week 9. Disintegration usually occurs within 11-12 wk, although the degradation rate is dependent on the size, structure, temperature, pH and type of body tissue in which the stent is implanted[17].

Biodegradable polydioxanone stents were developed and licensed for the treatment of refractory benign esophageal strictures[18-22]. The experience with their use in intestinal strictures is encouraging but still in its early stages. Published information regarding intestinal biodegradable stenting is limited to a few small case series that are both prospective and retrospective and focus on patients with refractory anastomotic colorectal strictures following resection for rectosigmoid carcinoma[23-25]. Rejchrt et al[26,27] reported the placement of biodegradable stents in patients with stricturing CD. This was the sole report of such a use in the small bowel and proximal large bowel. Proximal stent insertion was accomplished by use of a custom made introducer inserted into an overtube after endoscope removal. The standard delivery system for esophageal implantation has an active length of 75 cm and can only be used for intestinal strictures up to the distal descending colon.

Intestinal insertion of biodegradable polydioxanone stents is technically possible and relatively simple. However, it has been associated with a significant rate of early stent migration. This issue may be solved by improvements in stent design and appropriate strategies such as clip placement in the upper flare of the stents. It is necessary to clarify whether pre-dilation of the stricture should be performed (unless there is an inability to pass the delivery system through the stricture) because the radial force of biodegradable stents appears to be sufficient to ensure adequate stent expansion. Severe mucosal hyperplastic reaction resulting in obstruction after biodegradable stenting has been documented in esophageal strictures[28,29] but not in intestinal strictures thus far. Most of these cases were treated successfully with single balloon dilation and resolved completely after stent degradation. Neither of these complications was observed in our patient.

In conclusion, early experience suggests that biodegradable polydioxanone stents may represent a new therapeutic option for CD patients with refractory bowel strictures or strictures in which balloon dilation is unsuitable. Further studies are necessary to fully assess their long-term efficacy and safety in this clinical setting.

P- Reviewers Mpoumponaris AM, Kim JW, Laasch HU S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN