Published online Oct 16, 2021. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v13.i10.451

Peer-review started: April 4, 2021

First decision: June 24, 2021

Revised: July 4, 2021

Accepted: July 29, 2021

Article in press: July 29, 2021

Published online: October 16, 2021

Processing time: 193 Days and 6.5 Hours

Opie’s “pancreatic duct obstruction” and “common channel” theories are generally accepted as explanations of the mechanisms involved in gallstone acute pancreatitis (AP). Common channel elucidates the mechanism of necrotizing pancreatitis due to gallstones. For pancreatic duct obstruction, the clinical picture of most patients with ampullary stone impaction accompanied by biliopancreatic obstruction is dominated by life-threatening acute cholangitis rather than by AP, which clouds the understanding of the severity of gallstone AP. According to the revised Atlanta classification, it is difficult to consider these clinical features as indications of severe pancreatitis. Hence, the term “gallstone cholangiopancreatitis” is suggested to define severe disease complicated by acute cholangitis due to persistent ampullary stone impaction. It incorporates the terms “cholangitis” and “gallstone pancreatitis.” “Cholangitis” refers to acute cholangitis due to cholangiovenous reflux through the foci of extensive hepatocyte necrosis reflexed by marked elevation in transaminase levels caused by persistent ampullary obstruction. “Gallstone pancreatitis” refers to elevated pancreatic enzyme levels consequent to pancreatic duct obstruction. This pancreatic lesion is characterized by minimal or mild inflammation. Gallstone cholangiopancreatitis may be valuable in clinical practice for specifying gallstone AP that needs urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with endoscopic sphincterotomy.

Core Tip: The term “gallstone cholangiopancreatitis” is suggested to specify gallstone acute pancreatitis complicated by life-threatening acute cholangitis due to persistent ampullary stone impaction and needs urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with endoscopic sphincterotomy. The term “gallstone cholangiopancreatitis” incorporates the terms “cholangitis” and “gallstone pancreatitis.” “Cholangitis” refers to acute cholangitis due to cholangiovenous reflux through the foci of extensive hepatocyte necrosis reflexed by marked elevation in transaminase levels caused by persistent ampullary obstruction. “Gallstone pancreatitis” refers to elevated pancreatic enzyme levels consequent to pancreatic duct obstruction, the pancreatic lesion that is characterized by minimal or mild inflammation.

- Citation: Isogai M. Proposal of the term “gallstone cholangiopancreatitis” to specify gallstone pancreatitis that needs urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2021; 13(10): 451-459

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v13/i10/451.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v13.i10.451

The presence of gallstones is an important etiologic factor for the development of acute pancreatitis (AP). Generally, obstruction of pancreatic outflow, which is frequently caused by transiently impacted stones at the ampulla of Vater, can cause gallstone AP[1]. Most patients with gallstone AP have a mild disease due to the eventual passage of stones, exhibiting rapid objective improvement. Nevertheless, the pathophysiology of severe disease in the remaining patients, refractory to conventional supportive therapy, remains controversial. In addition to the low incidence of gallstone AP in those with gallstones (3.4%[2], 7.7%[3]), the rapid disease course and the relative inaccessibility of pancreatic tissues for the examination of AP have hampered investigations of the mechanism of severe disease in gallstone AP[4]. Considering these issues, investigations in humans may rely on findings from either autopsies or emergency surgeries performed during the early disease course. Emergency surgeries were common until the 1980s; however, they are no longer a common practice. Based on autopsy findings, Eugene Opie proposed the “pancreatic duct obstruction” and “common channel” theories in 1901, which are generally accepted as explanations of the mechanisms involved in gallstone AP[4]. Opie’s postulates can be summarized as follows: (1) Stones impacted at the terminal bile duct or the ampulla of Vater obstruct the bile and pancreatic ducts simultaneously. The obstructed pancreatic juice and bile may be forced backward into the pancreatic and hepatic parenchyma and penetrate their surrounding tissues, causing interstitial edematous pancreatitis and/or fat necrosis (“pancreatic duct obstruction” theory) and tissue stain with bile pigments and/or jaundice, respectively; and (2) Small stones about 3 mm in diameter that are large enough to lodge at the duodenal orifice mostly measured 2 mm to 2.5 mm but too small to obstruct the bile and pancreatic duct orifices, convert both ducts into a continuous closed channel. Contraction of the gallbladder overcomes any slight pressure difference between the bile and pancreatic ducts, which may lead to repeated bile reflux into the pancreatic duct, causing necrotizing pancreatitis (NP) (“common channel” theory).

Pancreatic duct obstruction theory stipulates that simultaneous obstruction of both ducts due to the large stone size and very short length of the common channel causes AP. However, severe disease caused by persistent ampullary stone impaction combined with biliopancreatic obstruction remains controversial. This is one of the main issues considered in this opinion review.

Common channel theory elucidates the cause of NP due to gallstones. Animal models have shown that protease activation is highly dependent on calcium release[5], with bile acids inducing calcium-releasing signals and contributing to pancreatic acinar cell damage[6]. However, questions on the evidence of bile reflux into the pancreatic duct and the presence of impacted stones, which prevent wide acceptance of this postulate, have been raised. Recently, histological evidence of bile reflux into the pancreas as the cause of NP has been reported[7], and Opie’s long-speculated “common channel” theory that NP represents the primary action of bile has been proven. In a case in the 1980s reported by Isogai et al[7], the operative cholangiogram did not demonstrate any bile duct stones. However, it revealed reflux of contrast material into the pancreatic duct, suggesting that an “anatomic” common channel was converted into a “functioning” common channel[8]. Kelly[9] noted that a functioning common channel is necessary for bile reflux and favors stone passage. Thus, regarding the presence of no impacted stones, virtually all small stones of a size that settle in the narrow duodenal orifice and allow bile reflux into the pancreatic duct may be evacuated and passed soon after triggering NP, thereby providing no evidence of their former impaction[7,10].

Long common channels[11], which allow for communication between the two ducts using impacted stones at the duodenal orifice, are not universally present in patients with gallstone AP. Hernández and Lerch[12] observed that the migration of gallstones through the biliary tract induces functional stenosis at the sphincter of Oddi, and a common channel between the pancreatic and bile ducts can arise. In 1909, Opie and Meakins[13] reported a case of NP with an anomalous duct of Santorini with a relatively wide orifice. They concluded that duodenal contents might have regurgitated into the pancreatic duct, causing NP; enterokinase, which is the most potent activator of pancreatic proteolytic enzymes, is present in these duodenal secretions. The passage of stones may cause a similar patulous sphincter, permitting duodenopancreatic reflux[14]. However, it may be difficult to prove histologically the reflux as the cause of NP since duodenal contents have no pigment to indicate their presence.

As Opie noted, pancreatic lesions caused by impacted ampullary stones may be interstitial edematous pancreatitis, of which clinical symptoms usually resolve within the first week[15]. It can also be fat necrosis, which is probably caused by lipase (one of the few pancreatic enzymes that require no activation), phagocytized by macrophages that may later be replaced with small foci of fibrotic tissues[16]. Acosta et al[17] noted that during the early stage of gallstone AP with persistent ampullary obstruction, a possible pancreatic complication is a pancreatic phlegmon, which includes a pancreatic inflammatory mass, peripancreatic fluid, and fat necrosis. Similarly, Oría et al[18] noted that biliopancreatic obstruction does not, by itself, contribute to persistent pancreatic inflammation or its worsening. Moreover, whether pancreatic duct obstruction without reflux causes NP in humans remains unknown[4]. Additionally, the clinical picture of most patients with ampullary stone impaction is often dominated by cholangitis and septicemia rather than by AP[14], which clouds the understanding of the severity of gallstone AP and leads to confusion and controversy regarding the management of patients with gallstone AP.

As noted previously, during the era of Opie, macroscopic findings of fat necrosis and/or interstitial edematous pancreatitis and those of jaundice and/or tissue stain with bile pigments were the indicators of persistent pancreatic duct and bile duct obstruction, respectively. The current availability of biochemical tests has shown that patients with gallstone AP have highly elevated liver and pancreatic enzyme levels during the early disease course. A histopathological study of liver biopsy specimens in gallstone AP patients with minimal or mild pancreatic inflammation (few patients with NP underwent liver biopsy) have shown that elevated serum transaminase levels reflect histopathological acute inflammatory hepatocyte necrosis (accumulation of neutrophils in and around the disappeared liver cell plate) and acute cholangitis (neutrophil infiltration in and around the bile duct lumen in the portal triad)[19]. Using electron microscopy, a disorganized liver cell plate, retained biliary material in the dilated canaliculi, and cytoplasm shedding into the Disse space have also been detected[19]. Thus, highly elevated liver enzyme levels during the early disease course in patients with gallstone AP reflect microscopic hepatocyte necrosis and cholangitis caused by the sudden blockage of the ampulla of Vater because of migrating bile duct stones[19]. Liver enzymes escape from degenerated and necrotic hepatocytes, causing marked hypertransaminemia. These hepatic histopathological simultaneous changes of cholestasis, acute cholangitis, and hepatocyte necrosis were consistent with those observed in patients with gallstone hepatitis[20], which will be discussed later. Based on the hepatic histopathological changes in gallstone AP, Neoptolemos et al[21] concluded that there is a degree of obstruction in both bile and pancreatic ducts in gallstone AP. In contrast, the admission serum bilirubin reflects the degree of “persistent” bile duct obstruction due to the continued presence of bile duct stones. Thus, the elevation of serum transaminase is consistent with the concept of transient ampullary obstruction in gallstone AP and useful in establishing gallstone etiology. An elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) level is widely considered the most useful to identify the biliary etiology of AP, and a 1994 meta-analysis found that an ALT level of > 150 units/L has a positive predictive value for gallstone AP of 95%[22]. A prospective study conducted by Anderson et al[23] demonstrated that the higher the ALT, the more likely a biliary cause becomes; ALT levels of > 300 units/L and > 500 units/L have positive predictive values of 87% and 92%, respectively.

In 1991, Isogai et al[20] proposed the term “gallstone hepatitis” as a new clinical entity defined as a marked elevation in serum transaminase levels due to acute inflammatory liver cell degeneration and necrosis during the early stage of gallstone impaction in the bile duct. Marked elevation in transaminase levels alone may lead to a diagnosis of so-called hepatitis. However, the pathogenesis of gallstone hepatitis differs from ordinary hepatitis in that hepatocyte necrosis does occur as a consequence of cholestasis. Hepatocellular degeneration and necrosis have been histologically shown to be the acute inflammatory reactions to liver injury caused by acute bile duct obstruction, which is transient and reversible after its early resolution[20]. It is easily conceivable that if the bile duct is obstructed by impacted stones, it becomes a closed system filled with bile and that pathological changes in the bile duct such as bile stasis, increased pressure, or infection may affect the liver cells that bound the bile canaliculus and cause hepatocellular injury[20]. Mayer and McMahon[24] reported that transient ampullary obstruction causes a rapid rise in bile duct pressure and consequent liver cell damage. Animal models showed that a combination of bile stasis and inflammation causes a mechanical insufficiency of lymph circulation, leading to extensive liver cell necrosis[25]. In addition to a marked depression of the hepatic microcirculation, increased neutrophil infiltration in the liver represents a potential source of liver injury during acute biliary obstruction[26]. In about half of patients with gallstone hepatitis, the gross appearance of the gallbladder showed acute cholecystitis. However, acute cholecystitis was significantly more infrequent among patients with gallstone hepatitis than control patients, and acute inflammation of the gallbladder is thought to be secondary to bile duct obstruction[20]. Similarly, histological evidence of acute cholangitis is considered after bile duct obstruction and not the initial process responsible for transaminase elevation[20]. In 2016, Huh et al[27] proposed to exclude patients with acute cholangitis upon hospital admission from gallstone hepatitis. Marked elevation of serum transaminase levels is induced under conditions in which intrabile duct pressure dramatically surges[27].

These highly elevated liver test results (gallstone hepatitis) should heighten the clinician’s awareness of coexisting acute biliary tract disease with gallstone AP. Hepatocytes with tight junctional complexes, which form a seal between the lumen of the bile canaliculus and the hepatic intercellular space, play a role in the creation of a canaliculi–sinusoidal barrier[28], and discontinuities in the junctional meshwork provide a direct pathway between the lumen of the bile canaliculus and the intercellular space[29]. Thus, elevated liver enzyme levels, a serological reflection of microscopic hepatocyte necrosis, indicate disruption to the barrier. It permits regurgitation of the bile into the circulating blood if the pressure in the bile canaliculus increases further due to persistent obstruction of the bile duct leading to acute ascending cholangitis.

Conventionally, clinicians have paid less attention to hepatobiliary diseases characterized by markedly elevated liver enzyme levels caused by impacted bile duct stones; this seems to be the Achilles heel in managing patients with gallstone AP. This may be unavoidable because the term “gallstone AP” refers to “pancreatitis” alone. The term “gallstone hepatopancreatitis” reflects elevated liver and pancreatic enzyme levels, which may better direct the clinician’s attention to hepatobiliary pancreatic lesions occurring in both the liver and the pancreas caused by transiently impacted stones at the ampulla of Vater early in the gallstone AP course.

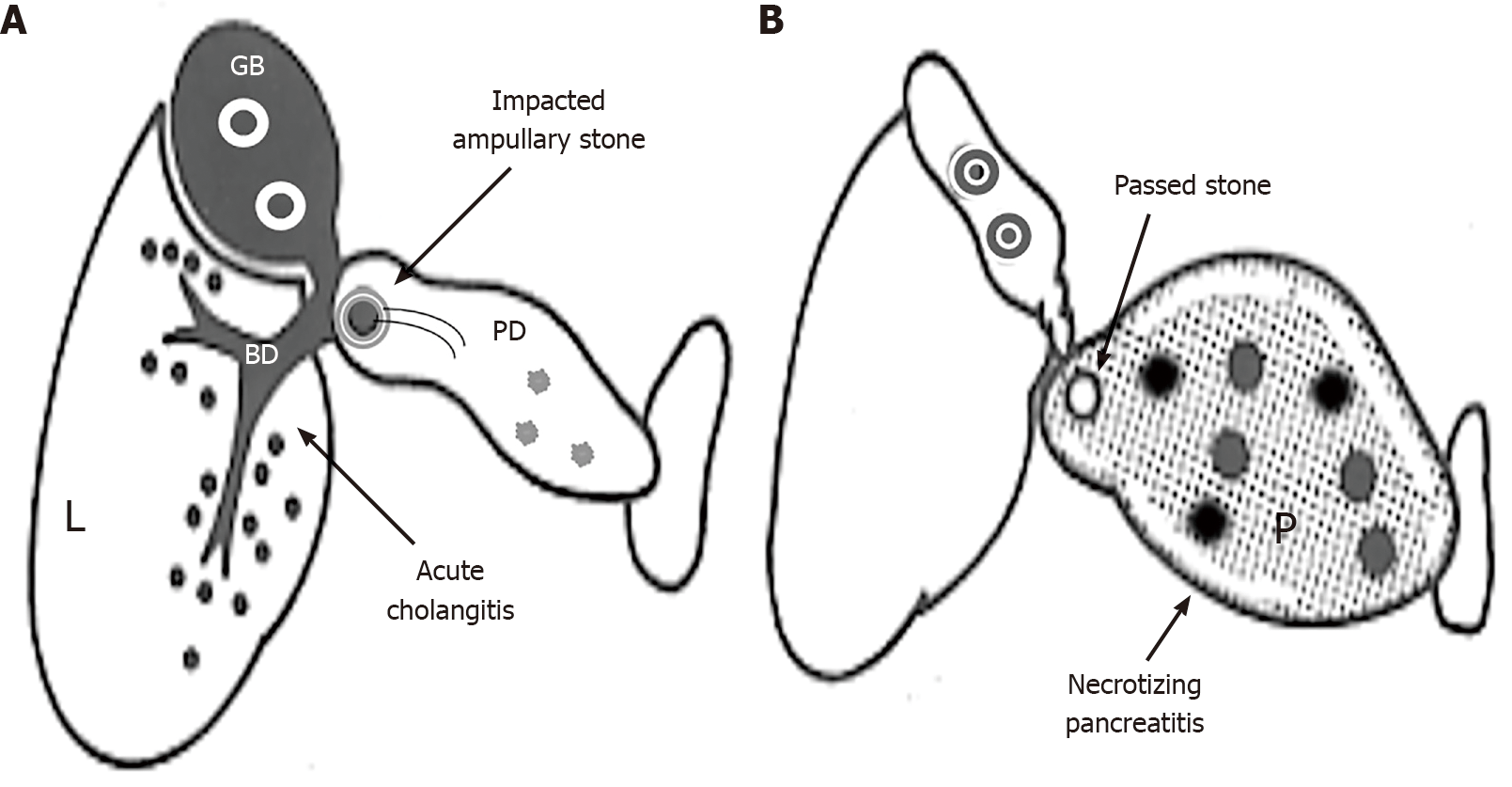

The revised Atlanta classification for AP defines moderately severe and severe AP as the presence of transient organ failure, local complications, or exacerbation of comorbid diseases and as persistent organ failure, respectively[15]. Subsequently, a clinical dilemma arises: Are those patients with AP of gallstone etiology (i.e. gallstone AP) who have minimal or mild pancreatitis complicated with life-threatening acute cholangitis due to persistent ampullary stone impaction diagnosed with moderately severe or severe AP? It is difficult to consider these clinical features to be indicative of such severity of AP. To cope with the dilemma mentioned above, the author suggests the term “gallstone cholangiopancreatitis (CP)” to define severe disease with minimal or mild pancreatitis complicated with life-threatening acute cholangitis. The term “gallstone CP” incorporates the terms “cholangitis” and “gallstone pancreatitis.” “Cholangitis” refers to acute ascending cholangitis due to cholangiovenous reflux through the foci of extensive hepatocyte necrosis reflexed by marked elevation in transaminase levels (gallstone hepatitis) caused by persistent ampullary obstruction. Conversely, “gallstone pancreatitis” refers to elevated pancreatic enzyme levels due to pancreatic duct obstruction, the pancreatic lesion that has minimal or mild inflammation (Figure 1A). It should be emphasized that in gallstone CP, the hepatobiliary pathology reflected by “cholangitis” outweighs the pancreatic lesion reflected by “gallstone pancreatitis.” Currently, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) is the widely accepted modality for gallstone AP with coexisting cholangitis and persistent biliary obstruction (i.e. gallstone CP )[10,30].

In contrast, NP resulting from the reflux of bile or duodenal contents into the pancreas uncomplicated with acute biliary tract disease due to the passage of stones is recommended to define “gallstone NP” (Figure 1B). This is because AP is generally an inflammation secondary to pancreatic tissue necrosis, irrespective of etiology, resulting from autodigestion by pancreatic enzymes[16]. Considering that stones responsible for NP generally pass into the duodenum early in the disease course or have already been evacuated and lost, ES may not be necessary for patients with gallstone NP. Additionally, a recent multicenter randomized controlled trial reported that compared with conservative treatment, urgent ERCP with ES (within 24 h after hospital presentation) did not reduce the composite endpoint of major complications or mortality in patients with predicted severe gallstone AP (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation Ⅱ score ≥ 8, Imrie score ≥ 3, or C-reactive protein level > 150 mg/L) and without cholangitis[31]. For future clinical trials on the role of urgent ERCP, American Gastroenterological Association has recommended that the timing of the ERCP interventions should be 24-48 h after diagnosis (24 h to allow spontaneous passage of the stone and 48 h to ensure that prolonged biliary obstruction does not occur)[10].

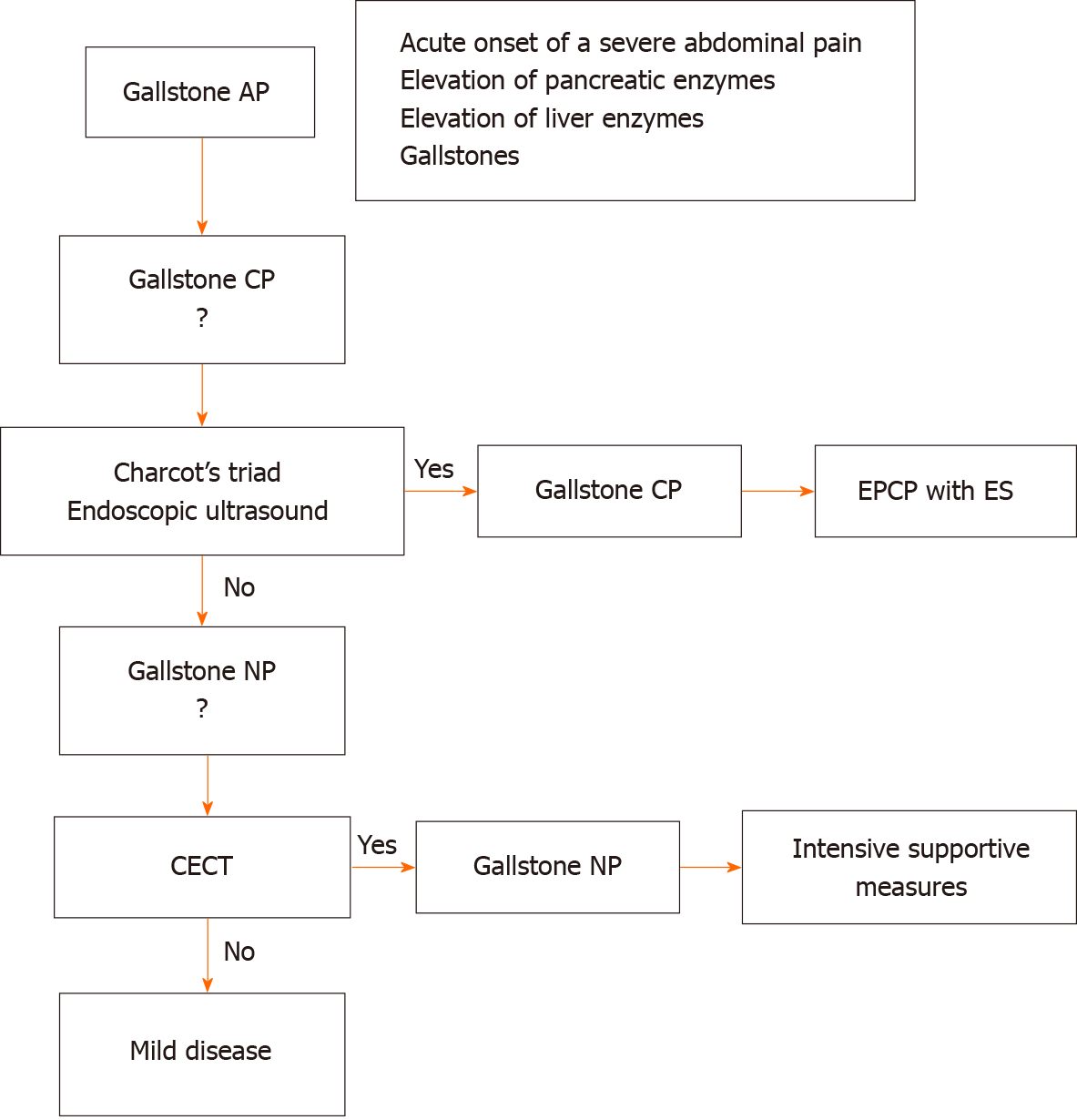

In 2017, Campos et al[32] reported that pancreaticobiliary diseases are the most common cause of the marked increase in serum aminotransferase levels, considering the decrease in the prevalence of liver diseases (including viral infections) due to vaccination programs, social awareness campaigns, and an increased incidence of cholesterol calculi in developed countries, which was considered to be a new paradigm. The marked increase in serum aminotransferase levels in pancreaticobiliary diseases observed by Campos et al[32] was specifically in gallstone hepatitis or gallstone AP. Thus, gallstone AP is expected to be more often encountered. Gallstone AP is a disease diagnosed by the abnormal biochemical data of pancreatic and liver enzymes or may be missed if the blood tests are not performed. Once gallstone AP is diagnosed based on the acute onset of a severe epigastric pain accompanied by an elevation of pancreatic and liver enzyme levels and gallstones are demonstrated by image modalities, it should be properly managed based on the differences in clinical features and the mechanism by which gallstones initiate AP. The acute inflammatory hepatobiliary disease indicated by marked hypertransaminasemia (gallstone hepatitis) together with the pancreatic lesion reflected by a pancreatic enzyme elevation needs to be evaluated.

Within the first 72 h following its diagnosis, the key management strategy is to predict patients with gallstone CP who will benefit from ERCP with ES. It may be difficult to distinguish the inflammatory response caused by pancreatic injury from that due to biliary sepsis. Additionally, the diagnosis of coexisting acute cholangitis is not always straightforward, and the reliance on Charcot’s triad criteria may be insufficient[18]. The sensitivity and specificity of endoscopic ultrasound in detecting common bile duct stones are superior to those of both transabdominal ultrasound and serum markers[33]. Hence, despite being invasive and not widely available, there is increasing use of endoscopic ultrasound to identify common bile duct stones in patients with gallstone AP. An endoscopic ultrasound-first strategy to establish the indication for ERCP with ES is expected[33].

If gallstone CP is ruled out and patients fail to improve after 5 to 7 d of initial treatment, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) is the most useful method for differentiating edematous pancreatitis from NP[34], and its findings are incorporated in the severity assessment of AP[35]. However, CECT should only be used when the value of the information obtained outweighs the disadvantages, such as impairment of renal function and allergic reaction[35]. Because an early CECT may underestimate the eventual extent of pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis, a non-enhancing area of the pancreatic parenchyma identified using CECT should be considered as pancreatic parenchyma necrosis after the first week of the disease[15].

The algorithm for the diagnosis and initial treatment of gallstone AP is shown in Figure 2. The detailed management strategy for patients with gallstone NP has been suggested by a substantial evidence base[33], although this issue is beyond the scope of the present review.

Regarding gallstone AP, the disease severity caused by persistent ampullary stone impaction with biliopancreatic obstruction remains controversial. Based on the differences in clinical features and the mechanism by which gallstones initiate AP, the severe disease is subdivided into gallstone CP and gallstone NP. The term “gallstone CP” is suggested to define severe disease with minimal or mild pancreatitis complicated by life-threatening acute cholangitis due to persistent ampullary stone impaction. The term “gallstone CP” may be valuable in clinical practice for specifying gallstone AP that needs urgent ERCP with ES. Whereas severe disease with NP resulting from the reflux of bile or duodenal contents into the pancreas is defined as “gallstone NP,” which is not complicated by acute biliary tract disease due to the passage of stones, and urgent ERCP may not be necessary.

Although elevation in serum transaminase levels in patients with gallstone CP reflects hepatic injury, which is inappropriate for use in multifactor prognostic systems of AP such as Ranson or Imrie score, the mechanism of transaminase elevation in patients with gallstone NP remains unclear without hepatic histopathological evidence, and further studies are needed.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Japanese Society of Clinical Surgery, No. 5292; Japanese Society of Abdominal Emergency Medicine, No. 501-756-1830.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Espinel J, João M, Krishna SG, Lashen SA, Maslennikov R S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Guo X

| 1. | Acosta JM, Ledesma CL. Gallstone migration as a cause of acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1974;290:484-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 439] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Moreau JA, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd, DiMagno EP. Gallstone pancreatitis and the effect of cholecystectomy: a population-based cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63:466-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Armstrong CP, Taylor TV, Jeacock J, Lucas S. The biliary tract in patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1985;72:551-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pandol SJ, Saluja AK, Imrie CW, Banks PA. Acute pancreatitis: bench to the bedside. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1127-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 450] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Krüger B, Albrecht E, Lerch MM. The role of intracellular calcium signaling in premature protease activation and the onset of pancreatitis. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:43-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Voronina S, Longbottom R, Sutton R, Petersen OH, Tepikin A. Bile acids induce calcium signals in mouse pancreatic acinar cells: implications for bile-induced pancreatic pathology. J Physiol. 2002;540:49-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Isogai M, Kaneoka Y, Iwata Y. Histological evidence of bile reflux in necrotizing pancreatitis: a case report. Med Case Rep Study Protoc. 2020;1:e0016. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kelly TR. Gallstone pancreatitis. Local predisposing factors. Ann Surg. 1984;200:479-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vege SS, DiMagno MJ, Forsmark CE, Martel M, Barkun AN. Initial Medical Treatment of Acute Pancreatitis: American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1103-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | DiMagno EP, Shorter RG, Taylor WF, Go VL. Relationships between pancreaticobiliary ductal anatomy and pancreatic ductal and parenchymal histology. Cancer. 1982;49:361-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hernández CA, Lerch MM. Sphincter stenosis and gallstone migration through the biliary tract. Lancet. 1993;341:1371-1373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Opie EL, Meakins JC. Data concerning the etiology and pathology of hemorrhagic necrosis of the pancreas (acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis). J Exp Med. 1909;11:561-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Obstruction or reflux in gallstone-associated acute pancreatitis? Lancet. 1988;1:915-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4330] [Article Influence: 360.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 16. | Klöppel G, Maillet B. Histopathology of acute pancreatitis. In: Beger HG, Warshaw AL, Büchler MW, Carr-Locke DL, Neoptolemos JP, Russell C, Sarr MG. The Pancreas—volume 1. Hoboken: Blackwell Science, 1998: 404-409. |

| 17. | Acosta JM, Katkhouda N, Debian KA, Groshen SG, Tsao-Wei DD, Berne TV. Early ductal decompression vs conservative management for gallstone pancreatitis with ampullary obstruction: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2006;243:33-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Oría A, Cimmino D, Ocampo C, Silva W, Kohan G, Zandalazini H, Szelagowski C, Chiappetta L. Early endoscopic intervention vs early conservative management in patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis and biliopancreatic obstruction: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2007;245:10-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Isogai M, Yamaguchi A, Hori A, Nakano S. Hepatic histopathological changes in biliary pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:449-454. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Isogai M, Hachisuka K, Yamaguchi A, Nakano S. Etiology and pathogenesis of marked elevation of serum transaminase in patients with acute gallstone disease. HPB Surg. 1991;4:95-105; discussion 106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Neoptolemos JP, Ogunbiyi O, Wilson PG, Carr-Locke DL. Etiology, pathogenesis, natural history, and treatment of biliary acute pancreatitis. In Beger HG, Warshaw AL, Büchler MW, Carr-Locke DL, Neoptolemos JP, Russell C, Sarr MG. The Pancreas. Volume 1. Hoboken: Blackwell Science; 1998. 521-547. |

| 22. | Tenner S, Dubner H, Steinberg W. Predicting gallstone pancreatitis with laboratory parameters: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1863-1866. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Anderson K, Brown LA, Daniel P, Connor SJ. Alanine transaminase rather than abdominal ultrasound alone is an important investigation to justify cholecystectomy in patients presenting with acute pancreatitis. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:342-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mayer AD, McMahon MJ. Biochemical identification of patients with gallstones associated with acute pancreatitis on the day of admission to hospital. Ann Surg. 1985;201:68-75. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Ruszyák I, Földi M, Szabó G. Lymphatics and lymph circulation: physiology and pathologY. In: Youlten L. London: Pergamon press, 1967: 727-735. |

| 26. | Koeppel TA, Trauner M, Baas JC, Thies JC, Schlosser SF, Post S, Gebhard MM, Herfarth C, Boyer JL, Otto G. Extrahepatic biliary obstruction impairs microvascular perfusion and increases leukocyte adhesion in rat liver. Hepatology. 1997;26:1085-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Huh CW, Jang SI, Lim BJ, Kim HW, Kim JK, Park JS, Lee SJ, Lee DK. Clinicopathological features of choledocholithiasis patients with high aminotransferase levels without cholangitis: Prospective comparative study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Boyer JL. Tight junctions in normal and cholestatic liver: does the paracellular pathway have functional significance? Hepatology. 1983;3:614-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Robenek H, Herwig J, Themann H. The morphologic characteristics of intercellular junctions between normal human liver cells and cells from patients with extrahepatic cholestasis. Am J Pathol. 1980;100:93-114. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Fogel EL, Sherman S. ERCP for gallstone pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:150-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Schepers NJ, Hallensleben NDL, Besselink MG, Anten MGF, Bollen TL, da Costa DW, van Delft F, van Dijk SM, van Dullemen HM, Dijkgraaf MGW, van Eijck CHJ, Erkelens GW, Erler NS, Fockens P, van Geenen EJM, van Grinsven J, Hollemans RA, van Hooft JE, van der Hulst RWM, Jansen JM, Kubben FJGM, Kuiken SD, Laheij RJF, Quispel R, de Ridder RJJ, Rijk MCM, Römkens TEH, Ruigrok CHM, Schoon EJ, Schwartz MP, Smeets XJNM, Spanier BWM, Tan ACITL, Thijs WJ, Timmer R, Venneman NG, Verdonk RC, Vleggaar FP, van de Vrie W, Witteman BJ, van Santvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Bruno MJ; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with sphincterotomy vs conservative treatment in predicted severe acute gallstone pancreatitis (APEC): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396:167-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Campos S, Silva N, Carvalho A. A New Paradigm in Gallstones Diseases and Marked Elevation of Transaminases: An Observational Study. Ann Hepatol. 2017;16:285-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | van Dijk SM, Hallensleben NDL, van Santvoort HC, Fockens P, van Goor H, Bruno MJ, Besselink MG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Acute pancreatitis: recent advances through randomised trials. Gut. 2017;66:2024-2032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Larvin M, Chalmers AG, McMahon MJ. Dynamic contrast enhanced computed tomography: a precise technique for identifying and localising pancreatic necrosis. BMJ. 1990;300:1425-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hirota M, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Hirata K, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Sekimoto M, Kimura Y, Takeda K, Isaji S, Koizumi M, Otsuki M, Matsuno S; JPN. JPN Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: severity assessment of acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:33-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |