Published online Jan 16, 2019. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v11.i1.22

Peer-review started: September 28, 2018

First decision: October 23, 2018

Revised: December 21, 2018

Accepted: December 29, 2018

Article in press: December 30, 2018

Published online: January 16, 2019

Processing time: 110 Days and 14.8 Hours

Per-oral pancreatoscopy (POPS) is an endoscopic procedure to visualize the main pancreatic duct. POPS specifically has the advantage of direct visualization of the pancreatic duct, allowing tissue acquisition and directed therapies such as stones lithotripsy. The aim of this review is to analyze and summarize the literature around pancreatoscopy. Pancreatoscopy consists of the classic technique of the mother-baby method in which a mini-endoscope is passed through the accessory channel of the therapeutic duodenoscope. Pancreatoscopy has two primary indications for diagnostic purpose. First, it is used for visualization and histological diagnosis of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. In these cases, POPS is very useful to assess the extent of malignancy and for the study of the intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm in order to guide the surgery resection margins. Second, it is used to determine pancreatic duct strictures, particularly important in cases of chronic pancreatitis, which is associated with both benign and malignant strictures. Therefore POPS allows differentiation between benign and malignant disease and allows mapping the extent of the tumor prior to surgical resection. Also tissue sampling is possible, but it can be technically difficult because of the limited maneuverability of the biopsy forceps in the pancreatic ducts. Pancreatoscopy can also be used for therapeutic purposes, such as pancreatoscopy-guided lithotripsy in chronic painful pancreatitis with pancreatic duct stones. The available data for the moment suggests that, in selected patients, pancreatoscopy has an important and promising role to play in the diagnosis of indeterminate pancreatic duct strictures and the mapping of main pancreatic duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. However, further studies are necessary to elucidate and validate the pancreatoscopy role in the therapeutic algorithm of chronic pancreatitis.

Core tip: Multiple modalities are available for the investigation of pancreatic diseases, such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, computed tomography, transabdominal ultrasound, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and endoscopic ultrasound. Per-oral pancreatoscopy was initially described in 1976. The available data suggests that in selected patients pancreatoscopy plays an important role in indeterminate pancreatic duct strictures and in evaluating the main pancreatic duct for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms following endoscopic ultrasound-fine needle aspiration prior to surgical treatment. Considering its therapeutic role, per-oral pancreatoscopy with lithotripsy has achieved a high rate of ductal clearance in patients with chronic calcific pancreatitis.

- Citation: De Luca L, Repici A, Koçollari A, Auriemma F, Bianchetti M, Mangiavillano B. Pancreatoscopy: An update. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2019; 11(1): 22-30

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v11/i1/22.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v11.i1.22

Per-oral pancreatoscopy (POPS) was initially described in 1976 by Kawai et al[1] in order to directly visualize the main pancreatic duct. Multiple modalities are available for the investigation of pancreatic diseases, such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, computed tomography, transabdominal ultrasound, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). Even though there have been technological refinements in these imaging modalities, making a conclusive diagnosis in the setting and managing indeterminate pancreatico-biliary stricture can be difficult[2]. POPS specifically has the advantage of directly observing the main pancreatic duct, permitting tissue acquisition, and directing therapies such as stones lithotripsy. The aim of this review is to analyze and summarize the literature around pancreatoscopy by elucidating its diagnostic and therapeutic roles in the management of pancreatic diseases.

Pancreatoscopy consists of the classic technique of the mother-baby method in which a mini-endoscope is inserted through the working channel of the duodenoscope. The early systems were improved by allowing the control of tip movement and adding a channel for irrigation and insertion of biopsy device or lithotripsy probe[3,4]. Pancreatoscopes with high definition images or virtual chromoendoscopy (narrow band imaging) (Figure 1) enhance the detail of the mucosal surface and blood vessels pattern improving the identification of tumors. One drawback of the mother-baby system is its dependence on two skilled operators to simultaneously control the separate endoscopes. In 2007 the first clinical experience with the single-operator cholangiopancreatoscopy system was reported (SpyGlass DVS, Boston Scientific)[5]. Later, in 2015, this system was upgraded to a digital version in order to improve image quality (SpyGlass DS, Boston Scientific)[6] (Figure 2).

Pancreatoscopes with small diameters (2.6-4 mm) can be inserted through the accessory channel of a therapeutic duodenoscope (minimum diameter of 4.2 mm) and a 0.035-inch guidewire, biopsy forceps, or a 1.9-Fr to 3-Fr electrohydraulic/laser lithotripsy can pass through the 1.2-mm working channel of a pancreatoscope. The image acquisition system is mediated by optical fibers connected to a light source with a video system.

Intraprocedural antibiotics are recommended in patients undergoing pancreatoscopy because there is a serious risk of infection due to systemic bacterial translocation during the duct saline irrigation[7].

Pancreatoscopy is performed by positioning the patient in the semi-prone configuration ensuring the stability of the duodenoscope, which is very important to facilitate the pancreatoscope insertion and eventual maneuvers. Access to the pancreatic duct is similar to that of the mother-baby cholangioscopy and commonly occurs through the major papilla, with or without sphincterotomy depending on the diameter of the pancreatic orifice and diagnostic indications, although it is also possible through the minor papilla[8]. For example, in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) where the papillary orifice is typically large, a sphincterotomy may be unnecessary.

However, the decision of whether or not to perform sphincterotomy prior to pancreatic duct cannulation is variable for diagnostic indications, but may be very helpful in cases of complex stones or stricture. Moreover, it would seem intuitive to recommend it because the diameter of the scope can be easily damaged when used in sub-optimal conditions, and this may have an impact on financial feasibility of the procedures. No data or guidelines have been published about this issue.

The pancreatoscope is advanced in the Wirsung duct on the guidewire to reach its caudal portion under regular irrigation and fluoroscopy (Figure 3). The passage of lithotripsy probes or biopsy forceps through the accessory channel can sometimes be difficult (although simpler than cholangioscopy in which the angulation is more accentuated and therefore decreases the maneuverability). The Spyglass system allows easier maneuverability within the Wirsung duct.

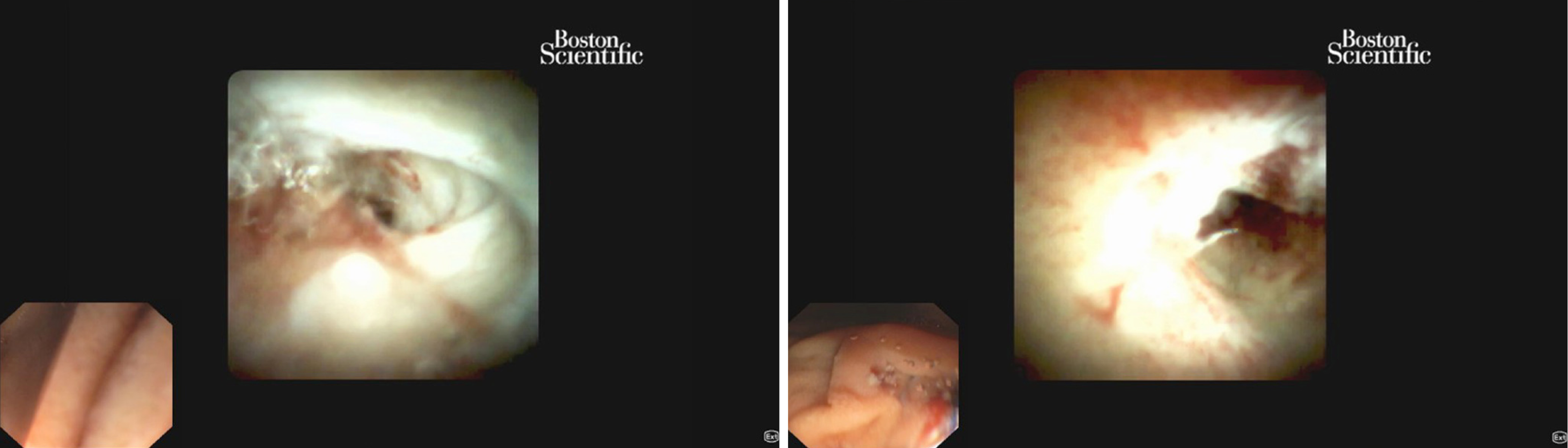

Similarly to cholangioscopy, a few years ago direct POPS was achieved using ultraslim gastroscopes through two approaches: (1) a 5-Fr balloon catheter positioned and inflated in the Wirsung duct in order to create an anchoring mechanism and facilitate the progression of the pancreatoscope[9] (Figure 4); and (2) an overtube placed on an ultra-slim gastroscope to prevent stomach looping during insertion[10,11] (Figure 5).

In patients without chronic calcific pancreatitis and/or pancreatic sphincterotomy, ductal injection is a high-risk maneuver for the development of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. In these cases some preventive measures are highly recommended (i.e., rectal indomethacin, hydration, stenting)[12-15].

Pancreatoscopy has two primary indications for diagnostic purpose. First, it is used for visualization and histological diagnosis of IPMNs[16]. Second, it is used to determine pancreatic duct strictures, differentiate between benign and malignant disease[17], and allow mapping the extent of the tumor prior to surgical resection[18]. Pancreatoscopy can also be used for therapeutic purposes, such as pancreatoscopy-guided lithotripsy in chronic painful pancreatitis with pancreatic duct stones[19]. Indications for pancreatoscopy are summarized in Table 1.

| Diagnostic |

| Visualization and histological diagnosis of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm |

| Determine pancreatic duct strictures, differentiate between benign and malignant disease allows mapping the extent of the tumor prior to surgical resection |

| Therapeutic |

| Pancreatoscopy-guided lithotripsy in chronic painful pancreatitis with pancreatic duct stones |

Pancreatoscopy in IPMN: One of the main indications of pancreatoscopy is to characterize the location and extent of IPMNs. The risk of malignancy within this type of tumors is highly variable, and they are distinguished in three different types: main duct, branch duct, and mixed-type IPMNs. Differential diagnosis is usually performed by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography because it helps to define adequate patient management[20]. While the branch duct IPMNs can be histologically malignant in a low rate of cases, main pancreatic duct IPMNs are malignant in 57%-92% of cases[21]. The primary utility of pancreatoscopy in main pancreatic duct IPMN is to confirm the diagnosis in equivocal cases. It is especially important when there is a question of chronic pancreatitis versus IPMN considering the history and imaging of the patient. Pancreatoscopy in these cases is very useful to assess the extent of malignancy and for the study of the IPMN in order to guide the surgery resection margins. On the other hand, pancreatoscopy should not be used to distinguish different subtypes of pancreatic cystic neoplasm[22].

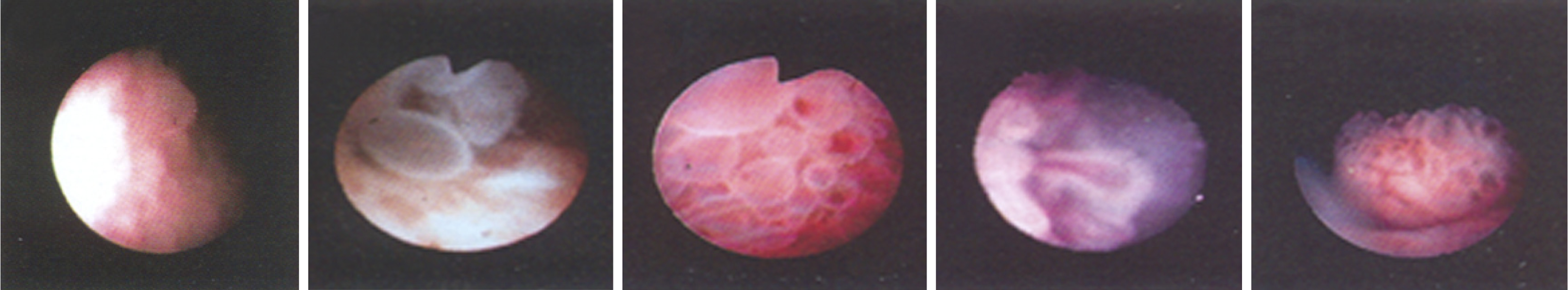

The appearance of protruding lesions on pancreatoscopy have been well classified by Hara et al[23]. This has allowed discrimination of malignant from benign IPMNs with an accuracy of 88% for main duct IPMNs and 67% for branch duct IPMNs. The classification consists of five groups (Figure 6): Type 1: Granular mucosa; Type 2: Fish-egg-like protrusions without vascular images; Type 3: Fish-egg-like protrusions with vascular images; Type 4: Villous protrusions; and Type 5: Vegetative protrusions. Hara et al[23] compared the pancreatoscopy findings to the histopathology of resected specimens in 60 patients with confirmed IPMNs. No case of malignancy was found in type 1 and 2, while type 3, 4, and 5 were found to be malignant, which included carcinoma in situ and invasive carcinoma. The presence of type 3, 4, and 5 lesions was 78% specific and 68% sensitive for malignancy.

Pancreatoscopy can be very useful to assess main duct IPMN extent pre-operatively. Tyberg et al[18] reported the first use of digital single-operator cholangiopancreatoscopy for pre-surgical mapping of pancreatobiliary malignancy. Sixty-two percent of their patients undergoing surgery for IPMN had a change in their surgical plan based on preoperative pancreatoscopy. Of these half required more extensive surgery and half required less extensive surgery. These results suggested an important and promising role of pancreatoscopy in IPMNs treatment. POPS-guided-tattoo may be a new technique developed in the near future to optimize IPMNs treatment.

Pancreatoscopy in indeterminate strictures of the main pancreatic duct: The conventional imaging modalities that are now widely used can often be insufficient to differentiate between benign and malignant pancreatic duct strictures. This is particularly important in chronic pancreatitis where it is possible discover both benign and malignant strictures[24,25]. Augmented endoscopy including narrow band imaging enhances visualization, which enhances detection of malignancies and improves diagnostic accuracy of POPS. As probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy allows in vivo identification of cellular and subcellular microstructures and thus permits a real-time histological diagnosis. In a retrospective analysis, El Hajj et al[26] evaluated patients undergoing pancreatoscopy with indeterminate pancreatic duct stricture (64%) or suspected IPMN (36%). The final diagnosis was based on surgical pathology. A pancreatic duct neoplasia was found overall in 41.8% of patients while the remaining cases had benign clinical features (benign strictures and branch IPMNs). The authors observed that pancreatic duct direct visualization had an 87% global accuracy in the differential diagnosis between benign and malignant lesions.

In conclusion, pancreatoscopy could be useful in differential diagnosis of indeterminate Wirsung duct strictures in all those selected cases where EUS-guided tissue acquisition (fine needle aspiration) does not provide conclusive findings[17,27].

Pancreatoscopy assisted-tissue sampling: Pancreatoscopy allows tissue sampling, but it can be technically difficult due to the poor maneuverability of the biopsy forceps inside the Wirsung duct. In a study published a decade ago[28] about patients with IPMN surgically resected, it was observed that the diagnostic sensitivity for malignant IPMN was significantly higher if the pancreatic juice was sampled through direct visualization during pancreatoscopy compared with catheter aspiration (68% and 38% respectively). Therefore, pancreatic juice sampling should always be taken into account for cytopathological examination, particularly in IPMN setting, in cases in which the EUS-fine needle aspiration is not contributive (for example due to the high viscosity of the mucus) or has provided inconclusive results[15]. El Hajj et al[26] reported high rates of diagnostic accuracy (87% sensitivity and 100% specificity) from pancreatic duct direct visualization or pancreatoscopy assisted biopsies for differentiating malignant from benign lesions.

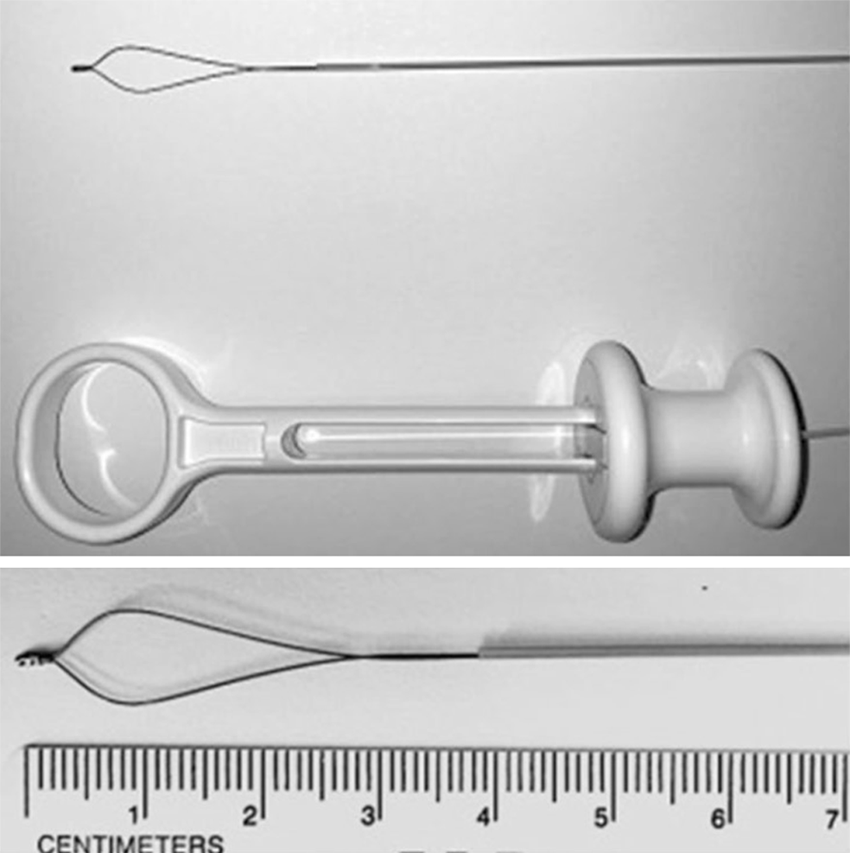

Pancreatoscopy with lithotripsy is indicated as a second line treatment in patients with chronic calcific pancreatitis and duct stones refractory to other treatments. In fact, even if endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for ductal clearance and pain relief are now the current standard techniques, available studies about pancreatoscopy using either electrohydraulic or laser lithotripsy have provided encouraging results. Both were effective and safe in the fragmentation of macrolithiasis. Moreover the possibility of obtaining direct visualization and accurately adjusting shock waves with probes increases the effectiveness by reducing complications such as bleeding, perforations, and wall duct damage. From a recently published systematic review[29], authors examined 10 studies (a total of 87 patients), none of which were randomized and only two prospective. The cohort study with more consistent data showed high technical and clinical success rates (70% and 74%, respectively)[30]. Another retrospective multicenter cohort study including a total of 28 patients who underwent pancreatoscopy-guided lithotripsy, Wirsung duct clearance was achieved in 79% and clinical success was found in 89% at a median follow-up of 13 mo[31]. Recent studies by Shah et al[32] and Navaneethan et al[6] obtained pancreatic duct clearance in 100% (7/7) and in 80% (4/5) of patients with lithotripsy (electrohydraulic and laser, respectively) using a single operator digital cholangiopancreatoscope. Overall, pancreatoscopy-guided lithotripsy appears to be effective although its precise role in the treatment of difficult-to-manage chronic painful pancreatitis with pancreatic duct stones remains unknown[33]. Moreover, the oncoming marketing of ancillary devices suitable for a single-operator cholangiopancreatoscopy system, such as the nitinol disposable minisnare (Figure 7) and minibasket (SpyGlassTM Retrieval Snare, Boston Scientific) could open new additional options for therapeutic procedures (i.e., stone fragments extraction, proximally migrated pancreatic stent capture and retrieval)[34].

The overall complication rates after diagnostic and therapeutic POPS were reported at 10%-12% and mostly consisted of mild pancreatitis[19,30]. The success of a pancreatoscopy can be conditioned by pancreatic main duct anatomy and diameter, ductal stenosis, or blocking stones. Depending on the clinical indication (as highlighted in the Pancreatoscopy in indeterminate strictures of the main pancreatic duct section) the visualization rate of Wirsung duct is 70%-80%. Some authors argue that a main pancreatic duct diameter greater than 5 mm is necessary.

Pancreatoscopy should be reserved to specific subgroups of patients with a limited scope of benefit. The available data suggests that in selected patients pancreatoscopy plays an important role in indeterminate pancreatic duct strictures and the mapping of main pancreatic duct IPMNs following EUS-fine needle aspiration prior to surgical treatment. Considering its therapeutic role, POPS with lithotripsy has achieved a high rate of ductal clearance in patients with chronic calcific pancreatitis and difficult-to-manage pancreatic duct stones, which are refractory with traditional techniques. Further studies are necessary to elucidate and validate the pancreatoscopy role in the therapeutic algorithm of chronic pancreatitis.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Friedel D, Hauser G, Umar M, Venu RP S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Song H

| 1. | Kawai K, Nakajima M, Akasaka Y, Shimamotu K, Murakami K. A new endoscopic method: the peroral choledocho-pancreatoscopy (author's transl). Leber Magen Darm. 1976;6:121-124. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Slattery JM, Sahani DV. What is the current state-of-the-art imaging for detection and staging of cholangiocarcinoma? Oncologist. 2006;11:913-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jung M, Zipf A, Schoonbroodt D, Herrmann G, Caspary WF. Is pancreatoscopy of any benefit in clarifying the diagnosis of pancreatic duct lesions? Endoscopy. 1998;30:273-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Howell DA, Dy RM, Hanson BL, Nezhad SF, Broaddus SB. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic duct stones using a 10F pancreatoscope and electrohydraulic lithotripsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:829-833. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Chen YK, Pleskow DK. SpyGlass single-operator peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for the diagnosis and therapy of bile-duct disorders: a clinical feasibility study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:832-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Navaneethan U, Hasan MK, Kommaraju K, Zhu X, Hebert-Magee S, Hawes RH, Vargo JJ, Varadarajulu S, Parsi MA. Digital, single-operator cholangiopancreatoscopy in the diagnosis and management of pancreatobiliary disorders: a multicenter clinical experience (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Othman MO, Guerrero R, Elhanafi S, Davis B, Hernandez J, Houle J, Mallawaarachchi I, Dwivedi AK, Zuckerman MJ. A prospective study of the risk of bacteremia in directed cholangioscopic examination of the common bile duct. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:151-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brauer BC, Chen YK, Ringold DA, Shah RJ. Peroral pancreatoscopy via the minor papilla for diagnosis and therapy of pancreatic diseases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:545-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cheon YK, Moon JH, Choi HJ, Lee JE, Lee YN, Cho YD, Lee TH, Park SH, Kim SJ. Direct peroral pancreatoscopy with an ultraslim endoscope for the evaluation of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E390-E391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Prachayakul V, Aswakul P, Kachintorn U. Overtube-assisted direct peroral pancreatoscopy using an ultraslim gastroscope in a patient suspected of having an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E279-E280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sung KF, Chu YY, Liu NJ, Hung CF, Chen TC, Chen JS, Lin CH. Direct peroral cholangioscopy and pancreatoscopy for diagnosis of a pancreatobiliary fistula caused by an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: a case report. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:247-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Buxbaum J, Yan A, Yeh K, Lane C, Nguyen N, Laine L. Aggressive hydration with lactated Ringer's solution reduces pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:303-7.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Elmunzer BJ, Scheiman JM, Lehman GA, Chak A, Mosler P, Higgins PD, Hayward RA, Romagnuolo J, Elta GH, Sherman S, Waljee AK, Repaka A, Atkinson MR, Cote GA, Kwon RS, McHenry L, Piraka CR, Wamsteker EJ, Watkins JL, Korsnes SJ, Schmidt SE, Turner SM, Nicholson S, Fogel EL; U. S. Cooperative for Outcomes Research in Endoscopy (USCORE). A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1414-1422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 504] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fan JH, Qian JB, Wang YM, Shi RH, Zhao CJ. Updated meta-analysis of pancreatic stent placement in preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7577-7583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Tringali A, Lemmers A, Meves V, Terheggen G, Pohl J, Manfredi G, Häfner M, Costamagna G, Devière J, Neuhaus H, Caillol F, Giovannini M, Hassan C, Dumonceau JM. Intraductal biliopancreatic imaging: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) technology review. Endoscopy. 2015;47:739-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Miura T, Igarashi Y, Okano N, Miki K, Okubo Y. Endoscopic diagnosis of intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas by means of peroral pancreatoscopy using a small-diameter videoscope and narrow-band imaging. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:119-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yamao K, Ohashi K, Nakamura T, Suzuki T, Sawaki A, Hara K, Fukutomi A, Baba T, Okubo K, Tanaka K, Moriyama I, Fukuda K, Matsumoto K, Shimizu Y. Efficacy of peroral pancreatoscopy in the diagnosis of pancreatic diseases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:205-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tyberg A, Raijman I, Siddiqui A, Arnelo U, Adler DG, Xu MM, Nassani N, Sejpal DV, Kedia P, Nah Lee Y, Gress FG, Ho S, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Digital Pancreaticocholangioscopy for Mapping of Pancreaticobiliary Neoplasia: Can We Alter the Surgical Resection Margin? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:71-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dumonceau JM, Delhaye M, Tringali A, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Poley JW, Arvanitaki M, Costamagna G, Costea F, Devière J, Eisendrath P, Lakhtakia S, Reddy N, Fockens P, Ponchon T, Bruno M. Endoscopic treatment of chronic pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2012;44:784-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang JY, Kimura W, Levy P, Pitman MB, Schmidt CM, Shimizu M, Wolfgang CL, Yamaguchi K, Yamao K; International Association of Pancreatology. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1714] [Cited by in RCA: 1614] [Article Influence: 124.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Falconi M, Shimizu M, Yamaguchi K, Yamao K, Matsuno S; International Association of Pancreatology. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1539] [Cited by in RCA: 1442] [Article Influence: 75.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas. European evidence-based guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gut. 2018;67:789-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1006] [Cited by in RCA: 896] [Article Influence: 128.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Hara T, Yamaguchi T, Ishihara T, Tsuyuguchi T, Kondo F, Kato K, Asano T, Saisho H. Diagnosis and patient management of intraductal papillary-mucinous tumor of the pancreas by using peroral pancreatoscopy and intraductal ultrasonography. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:34-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Acosta RD, Decker GA, Early DS, Eloubeidi MA, Evans JA, Faulx AL, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Foley K, Fonkalsrud L, Hwang JH, Jue TL, Khashab MA, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Pasha SF, Saltzman JR, Sharaf R, Shaukat A, Shergill AK, Wang A, Cash BD, DeWitt JM. The role of endoscopy in benign pancreatic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:203-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Munigala S, Kanwal F, Xian H, Agarwal B. New diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis: risk of missing an underlying pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1824-1830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | El Hajj II, Brauer BC, Wani S, Fukami N, Attwell AR, Shah RJ. Role of per-oral pancreatoscopy in the evaluation of suspected pancreatic duct neoplasia: a 13-year U.S. single-center experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:737-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kodama T, Koshitani T, Sato H, Imamura Y, Kato K, Abe M, Wakabayashi N, Tatsumi Y, Horii Y, Yamane Y, Yamagishi H. Electronic pancreatoscopy for the diagnosis of pancreatic diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:617-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yamaguchi T, Shirai Y, Ishihara T, Sudo K, Nakagawa A, Ito H, Miyazaki M, Nomura F, Saisho H. Pancreatic juice cytology in the diagnosis of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: significance of sampling by peroral pancreatoscopy. Cancer. 2005;104:2830-2836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Beyna T, Neuhaus H, Gerges C. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic duct stones under direct vision: Revolution or resignation? Systematic review. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:29-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Attwell AR, Brauer BC, Chen YK, Yen RD, Fukami N, Shah RJ. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with per oral pancreatoscopy for calcific chronic pancreatitis using endoscope and catheter-based pancreatoscopes: a 10-year single-center experience. Pancreas. 2014;43:268-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Attwell AR, Patel S, Kahaleh M, Raijman IL, Yen R, Shah RJ. ERCP with per-oral pancreatoscopy-guided laser lithotripsy for calcific chronic pancreatitis: a multicenter U.S. experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:311-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Shah RJ, Raijman I, Brauer B, Gumustop B, Pleskow DK. Performance of a fully disposable, digital, single-operator cholangiopancreatoscope. Endoscopy. 2017;49:651-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Miller CS, Chen YI. Current role of endoscopic pancreatoscopy. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2018;34:309-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Barakat MT, Banerjee S. SpyCatcher: Use of a Novel Cholangioscopic Snare for Capture and Retrieval of a Proximally Migrated Biliary Stent. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:3224-3227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |