Published online Nov 18, 2015. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i26.2696

Peer-review started: June 4, 2015

First decision: August 14, 2015

Revised: September 5, 2015

Accepted: October 20, 2015

Article in press: October 27, 2015

Published online: November 18, 2015

Processing time: 171 Days and 6.3 Hours

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH), also known as pseudolymphoma or nodular lymphoid lesion of the liver is an extremely rare condition, and only 51 hepatic RLH cases have been described in the literature since the first case was described in 1981. The majority of these cases were asymptomatic and incidentally found through radiological imaging. The precise etiology of hepatic RLH is still unknown, but relative high prevalence of autoimmune disorder in these cases suggests an immune-based liver disorder. Imaging features of hepatic RLH often suggest malignant lesions such as hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. In this report, we discuss two cases of hepatic RLH in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. We also present pathologic and magnetic resonance imaging findings, including one case utilizing a hepatocellular contrast agent, Eovist. Definitive diagnosis of hepatic RLH often requires surgical excision.

Core tip: Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver also known as pseudolymphoma is an extremely rare condition. Because of its rarity, association with underlying inflammatory liver disease and close resemblance to malignant hepatic lesions such as hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma on imaging studies, this rare lesion is frequently misdiagnosed. We discuss two cases of hepatic reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH) in patients with autoimmune hepatitis and how we came to the correct diagnosis. Definitive diagnosis of hepatic RLH often requires surgical excision.

- Citation: Kwon YK, Jha RC, Etesami K, Fishbein TM, Ozdemirli M, Desai CS. Pseudolymphoma (reactive lymphoid hyperplasia) of the liver: A clinical challenge. World J Hepatol 2015; 7(26): 2696-2702

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v7/i26/2696.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v7.i26.2696

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH) also known as pseudolymphoma[1-3] and nodular lymphoid lesion[4,5] is a condition characterized by localized non-neoplastic proliferation of lymphoid tissue at extranodal sites[6]. This rare condition is known to affect various organs including skin, orbit, thyroid, lung, stomach, breast, intestine, spleen and pancreas, however involvement of liver is extremely rare[6] and only 51 such cases have been reported to date[7-10]. Although the pathogenesis of hepatic RLH remains unclear, this condition is found to be associated with a number of chronic inflammatory and immunological conditions including viral hepatitis and various autoimmune diseases including autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune thyroiditis[6,11,12]. We report two cases of incidentally found hepatic lesion for which surgical excision was performed with a final diagnosis of hepatic RLH. We also describe magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and pathologic features of RLH, and review of current literature.

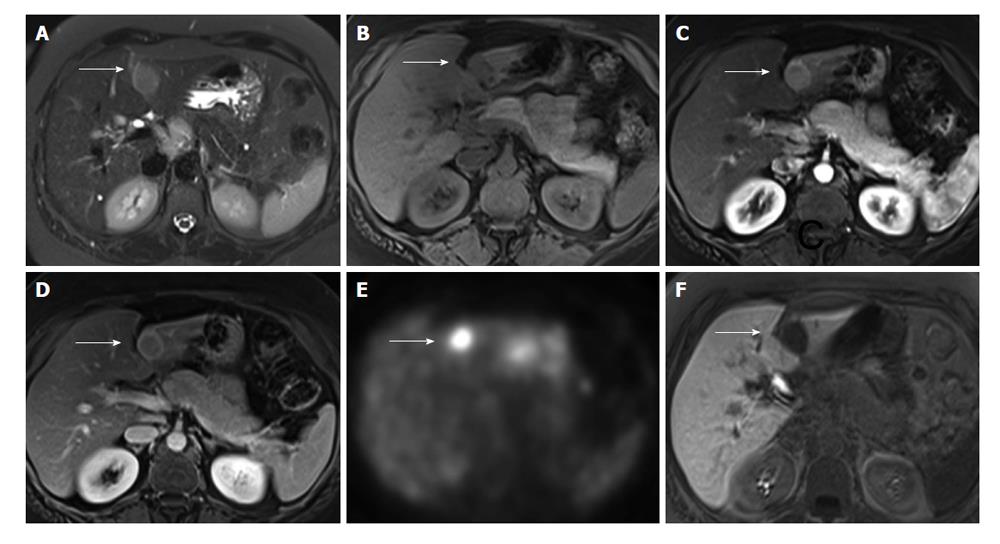

A 41-year-old Hispanic women with autoimmune hepatitis (ANA+, SMA+, IgG greater than 1.1-fold of upper normal limit) had an abdominal MRI at an outside hospital with conventional extracellular contrast agent as a part of elevated transaminase workup. The MRI demonstrated a non-cirrhotic liver with a single 2.5 cm lesion in segment 3 with hypervasular enhancement with washout (Figure 1A-D). Due to recent diagnosis of cervical cancer (stage 1B), positron emission tomography (PET) scan was performed (Figure 1E), which showed PET positivity. Metastatic disease was a concern, and as such, the patient underwent image guided needle biopsy of the liver lesion, which showed indeterminate lesion with unusual florid lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates. To further characterize the lesion, MRI was repeated in our institution with single dose of Eovist (Gadoxetate Disodium, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals), a liver specific contrast. This showed an arterial enhancement and lack of uptake on hepatocellular phase images most suggestive of a hepatic adenoma (Figure 1F). Due to the diagnostic uncertainties of this liver lesion, the patient underwent a surgical resection of the mass and also core biopsy of the non-tumoral area to assess the condition of the background liver.

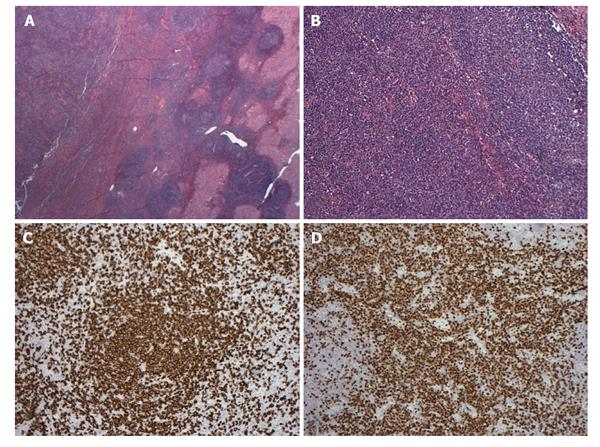

Pathologic examination of the resected specimen showed a 2.5 cm relatively well-circumscribed tumoral nodule containing lymphoid proliferation characterized by reactive lymphoid follicles and interfollicular plasma cells within the resected liver parenchyma (Figure 2A and B). Since lymphoma was suspected on initial evaluation, flow cytometric analysis, immunohistochemistry and polymerase chain reaction analysis for immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement were performed. Briefly, the flow cytometric analysis on the cells obtained from the tumor showed mixed population of CD2, CD5 and CD3 positive T cells with a CD4/CD8 4.5/1 (approximately 40%) and polyclonal CD19, CD20 and CD22 positive polyclonal B lymphocytes (60%) with no abnormal immunophenotype. Also with cytoplasmic kappa and lambda stains, clonality could not be demonstrated. These results were consistent with a reactive process. Immunohistochemical analysis showed numerous CD20 positive B cells mostly confined to follicles (Figure 2C) without abnormal immunophenotype and numerous interfollicular polyclonal CD138 and MUM-1 positive plasma cells (Figure 2D) with kappa/lambda ratio 3/1 within the lesion area. The majority of the plasma cells were IgG positive but negative for IgG4, CD56, CD117 and CD20. CD21 immunostain showed round follicular dendritic networks in follicles. Cyclin-D1 stain was negative. CD3, CD43 and CD5 highlighted the T-cells but they were negative on the B-cells. MIB-1 proliferative index was approximately 30% in interfollicular areas. Although these results were consistent with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, low grade marginal zone B-cell lymphoma was in the differential diagnosis. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis did not show monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement and excluded the possibility of a subtle B cell clonal process. In summary, our analysis ruled out a low grade extranodal marginal zone lymphoma and supported the diagnosis of RLH. The pathologic examination of the core biopsy of the liver from non-tumoral area showed steatohepatitis with portal lymphoid aggregates and plasma cells consistent with autoimmune hepatitis (grade 2, stage 2, data not shown).

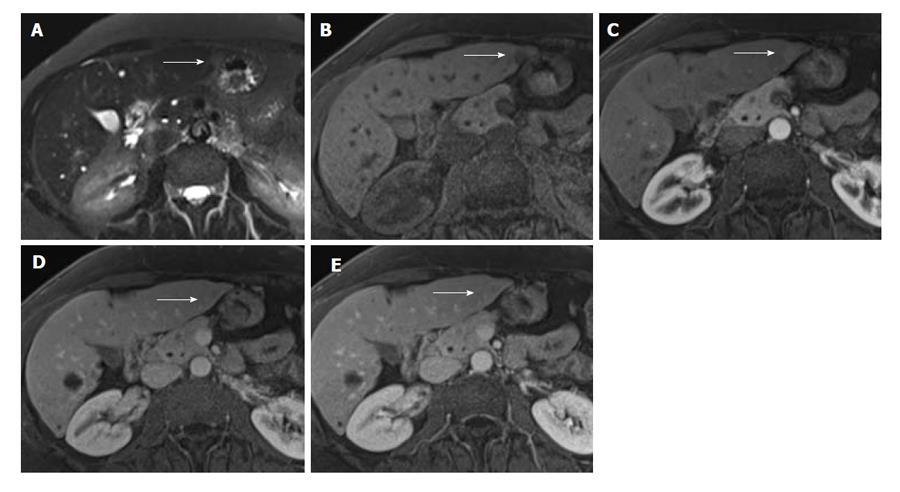

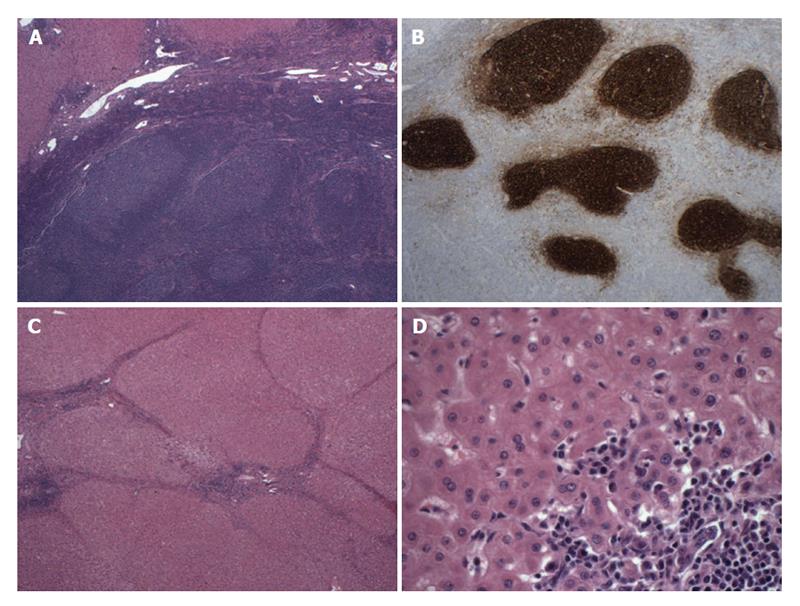

A 60-year-old African-American woman with chronic liver cirrhosis from autoimmune hepatitis (ANA+, SMA+) had a routine surveillance MRI, which showed a 1 cm lesion in segment 2 (Figure 3). The lesion had early contrast enhancement with washout, with features probable for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which is classified as Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System category 4 by American College of Radiology[13,14]. Similar to the above case, at the time of surgery, the initial evaluation of the liver nodule showed atypical lymphoid proliferation and thus, lymphoma workup was performed including flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry and PCR analysis. The pathologic examination showed a 1 cm relatively well-circumscribed tumoral nodule containing reactive lymphoid follicles and interfollicular plasma cells within liver parenchyma surrounded by regenerative nodules (Figure 4A). The flow cytometric analysis showed mixed population of polyclonal B cells and T cells with a CD4/CD8 ratio of 2.5/1 and with no abnormal immunophenotype consistent with a reactive process. The immunohistochemical analysis showed numerous CD20 positive B cells mostly confined to follicles, without abnormal immunophenotype, numerous T cells and polyclonal plasma cells with kappa/lambda ratio 3/1 within the lesion area. CD21 immunostain showed round follicular dendritic networks in follicles (Figure 4B). The results were consistent with a reactive process. PCR was also performed, which was negative for monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement. The sections of the adjacent liver parenchyma showed bridging fibrosis, portal and focal lobular lymphoid aggregates with plasma cells and focal nodule formation (Figure 4C and D). A diagnosis of RLH of liver in a background of autoimmune hepatitis was made.

Hepatic RLH is very rare presumably benign condition that may simulate malignancy on imaging studies[6,15] and low grade lymphoma especially extranodal marginal zone lymphoma on histology[16]. The mean age of hepatic RLH cases was 58 years with a marked female predominance with a male to female ratio of greater than 1:7[6]. The majority of cases were asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally, and more than half of the cases were associated with an underlying inflammatory or autoimmune condition like viral hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis or autoimmune thyroiditis[6]. The majority of cases, 81%, had a solitary tumor at presentation[11]. The average size was 15.4 mm with range 4 to 55 mm[6].

With the use of intravenous gadolinium-enhanced MRI, RLH lesion may resemble HCC and cholangiocarcinoma. In patients at risk for HCC, a lesion with imaging features of arterial phase enhancement and washout on later phase images, or presence of a capsule, is highly worrisome for HCC[13,14].

In our first case, the conventional contrast-enhanced MRI showed a non-cirrhotic liver with a single lesion with arterial enhancement and washout, and presence of a capsule. This lesion showed lack of uptake on hepatocellular phase of Eovist-enhanced MR images, which may be seen in HCC, hepatic adenoma, and argues against focal nodular hyperplasia. Given the normal background liver morphology, hepatic adenoma was the favored diagnosis. On PET scan, the lesion was PET positive; PET positivity has been previously reported one case[11]. Hypointensity on the hepatocellular phase of Eovist is consistent with findings previously reported[17].

In our second case, the background liver was noted to be cirrhotic, and a small lesion in segment 2 showed some features of arterial enhancement and faint washout, but a suggestion of subtle filling in on later delayed phase images. Abnormal increased signal intensity was also seen on T2 weighted images. These features were most consistent with malignancy, and with a differential diagnosis of HCC and cholangiocarcinoma or biphenotypic tumors[13,14].

Natural history of hepatic RLH is yet to be defined due to its rare occurrence. Although hepatic RLH is presumed to be a benign liver lesion, malignant transformation of RLH into lymphoma in other organs such as lung, stomach and skin has been well reported previously[18-20]. In liver, there is one case report by Sato et al[21] in 1999 where a hepatic RLH transformed into a low grade lymphoma in a 55-year-old patient with primary biliary cirrhosis and Sjogren’s syndrome. To our best knowledge, there are no other reports of malignant transformation or local or distant recurrence of RLH from various follow-up periods ranging from 3 mo to 15 years[6,22].

Although majority of the reported cases in literature were treated with surgical resection due to uncertain diagnosis, three cases were treated with liver transplantation due to associated liver disease[4,23]. Since this lesion occurs with pre-existing liver disease, it’s very important to consider this lesion in differential diagnosis before considering patients for transplants especially for oncological indication.

In conclusion, hepatic RLH will continue to present to clinicians as conundrum for correct diagnosis. Not much is known about this hepatic lesion, but up to 30% of the reported cases are associated with various autoimmune diseases[24]. Preoperative definitive diagnosis of hepatic RLH using various imaging modalities including MRI with hepatocellular agents such as Eovist is extremely difficult. Percutaneous needle aspiration or core biopsy may be helpful in differentiating hepatic RLH from metastatic carcinoma and primary liver tumors such as HCC. However, this approach may be inadequate in differentiating low-grade malignant lymphoma, particularly extranodal marginal zone lymphoma from RLH. Although extremely rare, one case of malignant transformation of hepatic RLH has been reported, and in other organs, RLH may undergo malignant transformation. Therefore, any patient with hepatic RLH should have close follow up. Based on limitations of imaging and pathology, for definitive diagnosis and treatment, surgical excision is the advised course.

Hepatic reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH) is an extremely rare condition, which is often misdiagnosed.

RLH is often associated with various autoimmune diseases, and the authors’ two patients had underlying autoimmune hepatitis.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), cholangiocarcinoma, and extranodal marginal zone lymphoma.

No specific lab values are associated with hepatic RLH.

With the use of intravenous gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, hepatic RLH lesion may resemble HCC and cholangiocarcinoma, often leading to misdiagnosis.

Pathologic examination of hepatic RLH shows lymphoid proliferation characterized by reactive lymphoid follicles and interfollicular plasma cells, often leading to misdiagnosis of lymphoma on initial evaluation.

Although hepatic RLH is presumably benign condition, surgical excision is the advised for definitive diagnosis and as a definitive treatment.

Misdiagnosis as HCC, cholangiocarcinoma or hepatic lymphoma will results in radically different treatment course, which may include liver transplant, major hepatic resection or chemotherapy.

Hepatic RLH is a presumably benign condition, which is associated with an underlying inflammatory or autoimmune condition like viral hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis or autoimmune thyroiditis.

Since 1981, 51 cases of hepatic RLH have been reported to date. Hepatic RLH should on the differential diagnosis especially when facing with hepatic lesion with underlying inflammatory or autoimmune condition without clear risk factors for HCC and cholangiocarcioma.

Well written case report on two patients with hepatic RLH and on work-up for the correct diagnosis.

P- Reviewer: Betrosian AP, Jin B, Lau WY S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Grouls V. Pseudolymphoma (inflammatory pseudotumor) of the liver. Zentralbl Allg Pathol. 1987;133:565-568. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Katayanagi K, Terada T, Nakanuma Y, Ueno T. A case of pseudolymphoma of the liver. Pathol Int. 1994;44:704-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim SR, Hayashi Y, Kang KB, Soe CG, Kim JH, Yang MK, Itoh H. A case of pseudolymphoma of the liver with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1997;26:209-214. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Sharifi S, Murphy M, Loda M, Pinkus GS, Khettry U. Nodular lymphoid lesion of the liver: an immune-mediated disorder mimicking low-grade malignant lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:302-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Willenbrock K, Kriener S, Oeschger S, Hansmann ML. Nodular lymphoid lesion of the liver with simultaneous focal nodular hyperplasia and hemangioma: discrimination from primary hepatic MALT-type non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Virchows Arch. 2006;448:223-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Amer A, Mafeld S, Saeed D, Al-Jundi W, Haugk B, Charnley R, White S. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver and pancreas. A report of two cases and a comprehensive review of the literature. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:e71-e80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yang CT, Liu KL, Lin MC, Yuan RH. Pseudolymphoma of the liver: Report of a case and review of the literature. Asian J Surg. 2013;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Song KD, Jeong WK. Benign nodules mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma on gadoxetic acid-enhanced liver MRI. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2015;21:187-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lv A, Liu W, Qian HG, Leng JH, Hao CY. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma: incidental finding of two cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:5863-5869. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Sonomura T, Anami S, Takeuchi T, Nakai M, Sahara S, Tanihata H, Sakamoto K, Sato M. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: Perinodular enhancement on contrast-enhanced computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6759-6763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hayashi M, Yonetani N, Hirokawa F, Asakuma M, Miyaji K, Takeshita A, Yamamoto K, Haga H, Takubo T, Tanigawa N. An operative case of hepatic pseudolymphoma difficult to differentiate from primary hepatic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zen Y, Fujii T, Nakanuma Y. Hepatic pseudolymphoma: a clinicopathological study of five cases and review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:244-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fowler KJ, Sheybani A, Parker RA, Doherty S, M Brunt E, Chapman WC, Menias CO. Combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma (biphenotypic) tumors: imaging features and diagnostic accuracy of contrast-enhanced CT and MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:332-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Liver imaging reporting and data system (LI-RADS) - American College of Radiology. [Accessed 2015 Aug 3]. Available from: http://www.acr.org/Quality-Safety/Resources/LIRADS. |

| 15. | Kobayashi A, Oda T, Fukunaga K, Sasaki R, Minami M, Ohkohchi N. MR imaging of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1282-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sibulesky L, Satyanarayana R, Menke D, Nguyen JH. Reactive nodular hyperplasia mimicking malignant lymphoma in donor liver allograft. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:1970-1972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yoshida K, Kobayashi S, Matsui O, Gabata T, Sanada J, Koda W, Minami T, Ryu Y, Kozaka K, Kitao A. Hepatic pseudolymphoma: imaging-pathologic correlation with special reference to hemodynamic analysis. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:1277-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Koss MN, Hochholzer L, Nichols PW, Wehunt WD, Lazarus AA. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and pseudolymphoma of lung: a study of 161 patients. Hum Pathol. 1983;14:1024-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brooks JJ, Enterline HT. Gastric pseudolymphoma. Its three subtypes and relation to lymphoma. Cancer. 1983;51:476-486. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kulow BF, Cualing H, Steele P, VanHorn J, Breneman JC, Mutasim DF, Breneman DL. Progression of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma to cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:519-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sato S, Masuda T, Oikawa H, Satoh T, Suzuki Y, Takikawa Y, Yamazaki K, Suzuki K, Sato S. Primary hepatic lymphoma associated with primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1669-1673. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Yuan L, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Cong W, Wu M. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: a clinicopathological study of 7 cases. HPB Surg. 2012;2012:357694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Domínguez-Pérez AD, Castell-Monsalve J. [Pseudolymphoma of the liver. Contribution of double-contrast magnetic resonance imaging]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;33:512-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ishida M, Nakahara T, Mochizuki Y, Tsujikawa T, Andoh A, Saito Y, Yamamoto H, Kojima F, Hotta M, Tani T. Hepatic reactive lymphoid hyperplasia in a patient with primary biliary cirrhosis. World J Hepatol. 2010;2:387-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |