Published online Jun 27, 2010. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v2.i6.239

Revised: May 4, 2010

Accepted: May 11, 2010

Published online: June 27, 2010

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary cancer of the liver. Prognosis and treatment options are stage dependent. In general, prognosis of patients with unresectable HCC is poor, especially for those patients with impaired liver function. Whereas treatment with the novel molecular tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib (Nexavar) was shown to result in prolonged survival in patients with preserved liver function, its’ possible application in HCC-patients with strongly impaired liver function has not been clearly assessed. Here, we report on a 47-year-old male patient who presented with Child-Pugh class C liver cirrhosis and multifocal, non-resectable HCC. The patient was treated for 27 mo with Sorafenib, which was not associated with major drug-related side effects. During treatment, a reduction in tumour size of 24% was achieved, as assessed by regular CT scan. Moreover, within the 27 mo interval of stable tumour disease, liver function improved from Child-Pugh class C to class A.

- Citation: Roderburg C, Bubenzer J, Spannbauer M, O ND, Mahnken A, Ludde T, Trautwein C, Tischendorf JJ. Long-term survival of a HCC-patient with severe liver dysfunction treated with sorafenib. World J Hepatol 2010; 2(6): 239-242

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v2/i6/239.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v2.i6.239

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common malignancy worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related death[1-5]. Therapeutic options and prognosis are stage dependent. In the case of localized disease, prognosis has been significantly improved in the last decade due to progress in diagnostic techniques and introduction of combined modality therapy[1-3]. In the case of unresectable or metastatic disease, however, HCC is still associated with a poor prognosis, and systemic therapy with cytotoxic agents provides only marginal benefit[4-6]. The introduction of targeted therapies such as receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors represents a breakthrough in the management of HCC[3,6,7].

At present, the multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor Sorafenib is the first and only molecular targeted drug that has been approved for treatment of patients with advanced HCC[8]. Encouraging preclinical results in several human tumours and a large phase II trial including 137 patients with advanced HCC led to a multi-center trial with a randomized, placebo-controlled design[9]. The phase III Sorafenib HCC Assesment Randomized Protocol (SHARP) trial demonstrated a 31% decrease in risk of death with a median survival of 10.7 mo for the sorafenib arm versus 7.9 mo for placebo[10]. Similar results were acquired by the ASIAN-trial. However both trials were restricted to patients with non-impaired liver function (Child-Pugh class A). Whether patients with impaired liver function can safely be treated with sorafenib and how this treatment might influence liver function and tumour progression is presently unclear.

A 47-year-old Egyptian patient was referred to our outpatient unit with clinical signs of chronic liver insufficiency. The patient was diagnosed with liver cirrhosis in 1996, caused by long-term ethanol abuse (stopped in 2001) and a hepatitis C infection after vaccination in Egypt in 1993. Between October 1997 and 2002 different interferon- and interferon/ribavirin-based therapies were conducted and finally discontinued due to non-response and at the request of the patient. Between 2002 and May 2007 no clinical visit was documented. In May 2007 laboratory testing and a sonography of the abdomen was performed during an external clinical visit. No hepatic lesions suspect for HCC were observed at this time-point. Liver function was severely reduced with a Child-Pugh score of 12 (Child-Pugh class C).

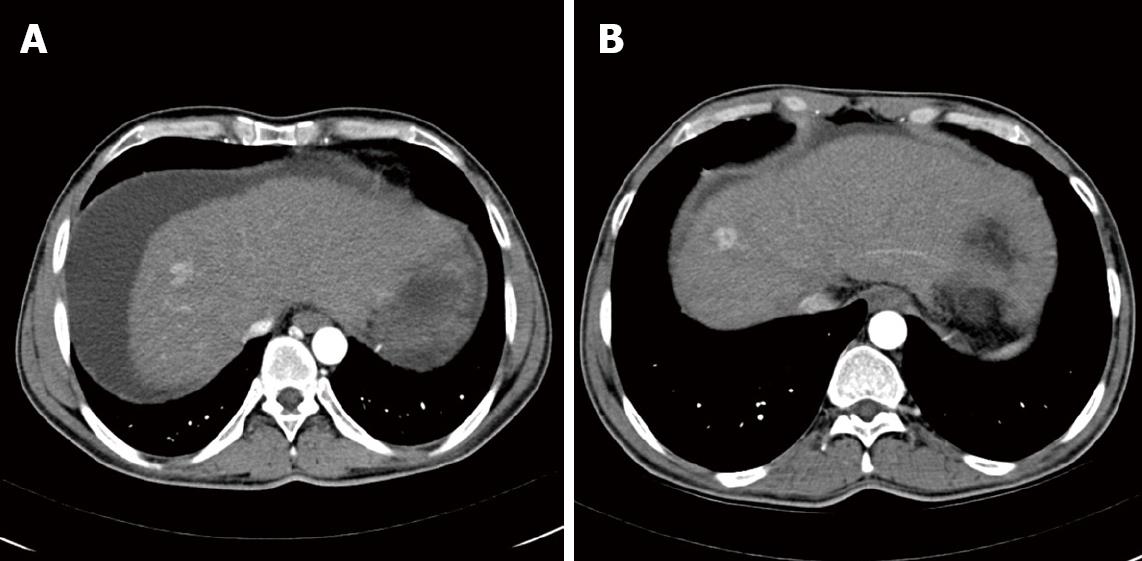

On admission to our outpatient unit in September 2007, blood tests showed a severe impairment of liver function (Bilirubin 5.6 mg/dL, Albumin 28 g/L, Quick 48%) and a mild rise in alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level (17 μg/L). No ethanol was detected in the serum. Furthermore serum gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) as well as serum triglycerides were within the normal limits, indicating long-term alcohol abstinence. Clinically the patient showed jaundice of skin and sclera and stage 1 encephalopathy. Taken together, these data resulted in a Child-Pugh score of 12 (Child-Pugh class C). Ultrasound examination of the abdomen demonstrated a hepatic mass in liver-segment VII accompanied by portal hypertension, massive ascites and severe meteorism, limiting the sensitivity of this examination to detect smaller lesions. Arterial phase contrast-enhanced multi-slice spatial computed tomography (MSCT) confirmed this lesion and further lesions [lobus caudatus (7 mm × 8 mm); segment II (5 mm × 3 mm); segment VI/VII (12 mm × 17 mm) and segment VIII (17 mm × 18 mm and 23 mm × 14 mm)] became apparent (Figure 1). Furthermore, two lesions smaller than 5 mm in largest diameter (segment IIb and VIII) were described. In order to further discriminate between HCC and benign lesions (such as hyperplastic nodules) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with a liver specific contrast agent was performed. Here five lesions suspect for HCC became apparent, strongly suggesting the presence of a multifocal HCC. After evacuation of 3.5 L ascites, a CT-guided puncture of the hepatic lesion in segment VIII was performed. Pathological analysis confirmed the presence of a well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (G2). Neither on MSCT scan nor in MRI was extrahepatic tumour spread detected.

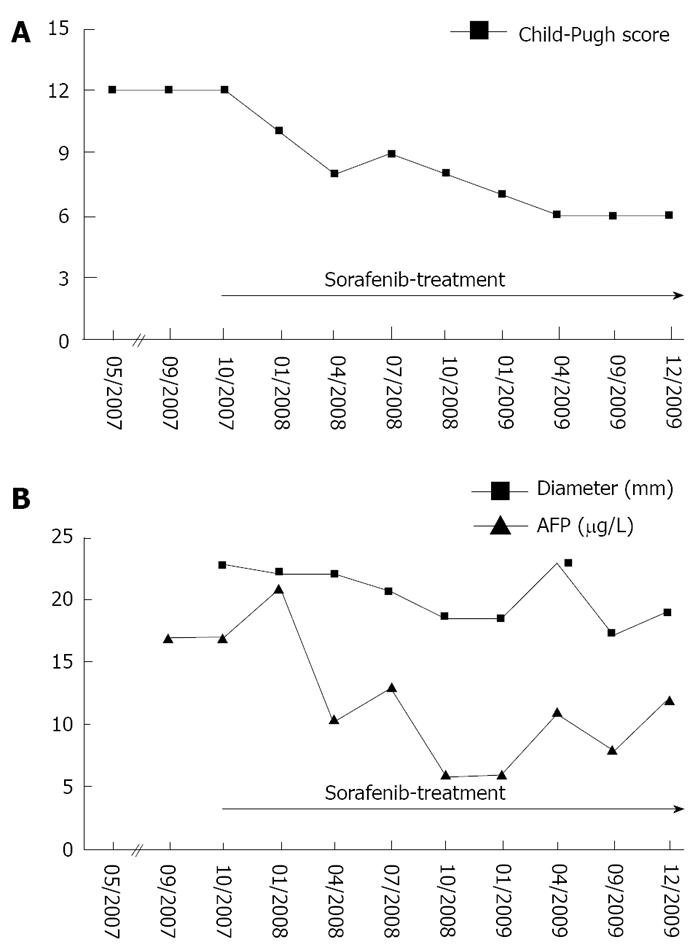

Overall, the patient was classified as BCLC stage D, suggesting treatment focussed on palliation as the remaining therapeutic option. However, considering the young age of the patient, the presence of a hepatitis C infection and the lack of extrahepatic tumour spread, the potential risks and benefits of a treatment with 800 mg sorafenib daily were discussed with the patient. This therapy was initiated in October 2007 and has continued until now. Regular clinical evaluations have included physical examination and laboratory testing (complete blood count, creatinine, ALT, AST, AP, GGT and Quick) every 4 wk. CT scans with intravenous and oral contrast of the abdomen have been performed every three months. As depicted in Figure 2, on admission the patient presented with a Child-Pugh score of 12 (MELD score: 19). The lesion in segment VIII with a diameter of 22.8 mm was chosen as a reference for evaluation of tumour growth. After the onset of sorafenib treatment a 24% reduction in tumour size was achieved as the best radiological response, corresponding to long-term (27 mo) tumour control. Interestingly evaluation of tumour mass by serum AFP measurements and MSCT were in perfect correlation (Figure 2B). In the meantime an intensified diuretic treatment with spironolactone and torasemide was introduced, leading to continuous improvement of liver function (no signs of encephalopathy, mild ascites, Bilirubin 1.2 mg/dL, Albumin 35.1 g/L, Quick 82%; MELD score: 9) and a down-staging of impairment of liver function according to the Child-Pugh score from Child-Pugh class C to class A (Figure 2A). Currently the patient is stable under a combination-therapy with spironolactone (100 mg daily) and torasemide (20 mg daily). Given the improvement of liver function, local ablative therapy was proposed but is currently rejected by the patient. The option of liver transplantation was rejected due to excessive tumour load according to the Milano criteria (> 3 lesions) and lack of a living liver donor.

Sorafenib-treatment was well tolerated over the whole time; only one event of grade 3 diarrhoea was reported.

Advanced or non-resectable hepatocellular carcinoma has a poor therapeutic outcome. For many patients, therapeutic options are limited to palliation[3-5]. Only recently, molecular targeted therapy such as sorafenib has become an option for treatment of patients with advanced HCC[6,7,11]. Sorafenib is one of the new molecular targeted agents that inhibits both proangiogenic (VEGFR-1, -2, -3; PDGFR-β) and tumorigenic (RET, Flt-3, c-Kit) receptor tyrosine kinases. It also inhibits the serine/threonine kinase Raf-1. Raf-1 has been shown to be activated in a wide range of human malignancies and is therefore recognized as a strategic target for therapeutic drug development. Thus, sorafenib has been proven to be effective in a wide range of solid tumours comprising renal cell carcinoma, melanoma and hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting proangiogenic and proapoptotic pathways.

Sorafenib demonstrated a significant survival benefit in patients with non-resectable or advanced HCC in the SHARP- and the ASIAN- trial[10] and has become a treatment standard for HCC-patients in advanced stages of disease. A subgroup analysis of both studies showed that those patients lacking extrahepatic tumor spread and chronic hepatitis C infection benefit particularly from treatment with sorafenib. This may be due to the fact that chronic hepatitis C induces signalling via Ras/Raf-pathway, which is one of the main targets of sorafenib. However, the positive outcome of these studies applied only to Child-Pugh class A and a few of Child-Pugh class B patients. The question of the efficacy and safety of sorafenib treatment of patients with impaired liver function had therefore remained unanswered. In a large phase II trial including 137 patients with advanced HCC, 28% of patients were classified as Child-Pugh class B. Pharmacokinetic parameters showed no difference in patients with cirrhosis Child-Pugh class A and B, and common adverse events associated with sorafenib were similar[9]. However, cirrhosis worsened more frequently in Child-Pugh class B patients[9]. It remained unclear whether this was a drug-related effect or was caused by disease progression. While differences in sorafenib pharmacokinetics between Child-Pugh class A and B patients were not clinically significant, study-based safety data are not available for patients with Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis[9]. To our knowledge there are only two reports on sorafenib treatment of HCC patients with Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis. Pinter et al. and Wörns et al. report on ten and four patients, respectively, treated with sorafenib. Based on their data, they concluded that sorafenib had no significant benefit in patients with high grade impaired liver function because of their limited life expectancy (OS < 3 mo) and lack of improvement in clinical parameters[12,13].

In sharp contrast to these data, we here report the case of a HCC-patient with Child-Pugh C liver cirrhosis who has experienced a long-term (27 mo) phase of stable tumour disease under treatment with sorafenib. On admission the patient displayed a Child-Pugh score of 12 [at this time since at least 5 months lasting (May 2007-Octobre 2007)] and seven hepatic HCC-lesions, as shown by MRI/ MSCT scan. The AFP level was only slightly enhanced, which is consistent with the fact that up to 20% of HCC patients do not produce AFP during the course of the disease[14,15]. During the period of treatment with sorafenib we observed a reduction in tumour size of 24%, corresponding to stable disease according to RECIST criteria.

In addition hepatological treatment such as optimization of nutrition and lifestyle as well as optimization of medication (e.g. diuretics) was implemented and resulted in an improvement of Child-Pugh score from class C to class A (score 12 to score 6). Given the improved liver function, the patient became suitable for treatment concepts such as TACE which are currently rejected by the patient due to the risk of worsening of liver function. Furthermore liver transplantation was considered as an option for this patient. Liver transplantation represents a curative treatment modality for a selected patient population as defined by tumour burden. For HCC, liver transplantation only yields good results for patients whose tumour masses do not exceed the Milano-criteria (1 lesion ≤ 5 cm, or 2 to 3 lesions ≤ 3 cm)[16]. In recent years living donor liver transplantation has been discussed for patients exceeding these criteria[17]. However due to tumour load and lack of a liver donor neither cadaveric nor living donor liver transplantation were an option for the patient.

In summary these data suggest that for a highly selected population of HCC- patients (e.g. young age, lack of extrahepatic tumour spread, chronic HCV infection) sorafenib-treatment might be a well tolerated option even in cases of detoriated liver function.

Peer reviewers: Norberto C Chavez-Tapia, MD, PhD, Departments of Biomedical Research, Gastroenterology and Liver Unit, Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation, Puente de Piedra 150, Col. Toriello Guerra, Tlalpan 14050, Mexico City, Mexico; Cheng-Shyong Chang, MD, Assistant Professor, Attending physician, Division of Hemato-oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, Changhua Christian Hospital, 135, Nan-Hsiao St. Changhua, 500, Taiwan, China

| 2. | Rampone B, Schiavone B, Martino A, Viviano C, Confuorto G. Current management strategy of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3210-3216. |

| 3. | Wörns MA, Weinmann A, Schuchmann M, Galle PR. Systemic therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis. 2009;27:175-188. |

| 4. | Abou-Alfa GK, Huitzil-Melendez FD, O’Reilly EM, Saltz LB. Current management of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2008;2:64-70. |

| 5. | Blum HE. Hepatocellular carcinoma: therapy and prevention. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7391-7400. |

| 6. | Llovet JM, Bruix J. Molecular targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;48:1312-1327. |

| 7. | Kudo M. Hepatocellular carcinoma 2009 and beyond: from the surveillance to molecular targeted therapy. Oncology. 2008;75 Suppl 1:1-12. |

| 8. | Kane RC, Farrell AT, Madabushi R, Booth B, Chattopadhyay S, Sridhara R, Justice R, Pazdur R. Sorafenib for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist. 2009;14:95-100. |

| 9. | Abou-Alfa GK, Schwartz L, Ricci S, Amadori D, Santoro A, Figer A, De Greve J, Douillard JY, Lathia C, Schwartz B. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4293-4300. |

| 10. | Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390. |

| 11. | Blum HE. Molecular therapy and prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2003;2:11-22. |

| 12. | Pinter M, Sieghart W, Graziadei I, Vogel W, Maieron A, Königsberg R, Weissmann A, Kornek G, Plank C, Peck-Radosavljevic M. Sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma from mild to advanced stage liver cirrhosis. Oncologist. 2009;14:70-76. |

| 13. | Wörns MA, Weinmann A, Pfingst K, Schulte-Sasse C, Messow CM, Schulze-Bergkamen H, Teufel A, Schuchmann M, Kanzler S, Düber C. Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in consideration of concomitant stage of liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:489-495. |

| 14. | Zhou L, Liu J, Luo F. Serum tumor markers for detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1175-1181. |

| 15. | Debruyne EN, Delanghe JR. Diagnosing and monitoring hepatocellular carcinoma with alpha-fetoprotein: new aspects and applications. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;395:19-26. |

| 16. | Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A, Gennari L. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693-699. |

| 17. | Lee S, Ahn C, Ha T, Moon D, Choi K, Song G, Chung D, Park G, Yu Y, Choi N. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Korean experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;Epub ahead of print. |