Published online Jun 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i6.108558

Revised: May 13, 2025

Accepted: May 29, 2025

Published online: June 27, 2025

Processing time: 69 Days and 22.8 Hours

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS) is a rare genetic disorder that affects multiple organs, primarily the liver. Most patients are diagnosed during infancy or early childhood. As they grow older, the majority of affected children may experience spontaneous remission, and cases of cirrhosis in adults are rarely reported.

A 36-year-old male patient presented with massive ascites. Laboratory tests revealed pancytopenia and a serum-ascites albumin gradient greater than 1.1 g/dL. An abdominal computed tomography scan demonstrated cirrhosis, splenomegaly, pancreatic fat infiltration, and a substantial accumulation of peritoneal fluid. Gastroscopy identified esophageal varices. Liver stiffness measurement indicated a value of 32.7 kPa. Based on the results of auxiliary examinations, common causes of cirrhosis were excluded, and a mutation in the Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome gene was ultimately identified through whole-exome sequencing. The patient was diagnosed with cirrhosis secondary to SDS. Fo

Patients with liver cirrhosis who also exhibit pancreatic fat infiltration and pancytopenia necessitate further exon testing to exclude the possibility of SDS.

Core Tip: Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS) frequently results in abnormal liver function and hepatomegaly during infancy and early childhood. However, adult liver pathologies caused by SDS are rare. We present a unique case of a 36-year-old patient diagnosed with SDS through whole-exome sequencing, highlighting the possibility of SDS in cases of unexplained cirrhosis and pancreatic fat infiltration.

- Citation: Guo HJ. Adult presentation of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome complicated by liver cirrhosis and pancreatic fat infiltration: A case report. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(6): 108558

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i6/108558.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i6.108558

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS) is a rare hereditary disorder that can affect multiple organs, including the pancreas and bone marrow[1]. The liver is frequently involved, typically manifesting as hepatomegaly and elevated transaminase levels. SDS is more prevalent in infancy and early childhood, with symptoms often resolving spontaneously as the individual matures. While some children may progress to liver cirrhosis or liver failure, cases of adults developing liver cirrhosis are relatively uncommon.

We here report a case of adult liver cirrhosis resulting from SDS, aiming to explore the clinical characteristics, treatment options, and prognosis of liver lesions associated with this syndrome.

A 36-year-old male patient presented with abdominal distension and bilateral lower limb edema that had persisted for 20 days.

The patient exhibited abnormal liver function at the age of four, with symptoms of hepatitis that were alleviated following medical intervention. However, there has been no subsequent monitoring of liver function since that time. The patient presented with symptoms of abdominal distension and bilateral lower limb edema for the past 20 days, which were accompanied by a decrease in dietary intake. The patient reported no fever, abdominal pain, constipation, chest tightness, shortness of breath, or oliguria.

The patient did not have a history of diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, tuberculosis, chronic hepatitis B virus infection, chronic hepatitis C virus infection, or any other diseases.

The patient did not have a history of smoking or alcohol consumption, and there is no familial history of similar diseases.

Physical examination revealed that the patient exhibited no liver palms or spider angiomas, and jaundice was not observed in either the skin or sclera. The abdomen appeared distended, with no visible abdominal wall varicosities and no tenderness or rebound tenderness noted. The liver was not palpable; however, the spleen was palpable 5 cm below the left costal margin. Ascites was present, and there was severe pitting edema in both lower limbs.

Laboratory test results indicated that the patient had severe pancytopenia, characterized by a white blood cell (WBC) count of 1.04 × 109/L, a platelet count of 21 × 109/L, and a hemoglobin level of 82 g/L. Biochemical analysis yielded the following results: (1) Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 17.4 U/L; (2) Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 40.4 U/L; (3) Albumin of 27.6 g/L; (4) Total bilirubin (TBIL) of 3.2 mg/dL; (5) Cholinesterase of 2360 U/L; (6) Ceruloplasmin of 233 mg/L; and (7) Serum ferritin of 35 μg/dL. Coagulation function tests revealed an international normalized ratio of 2.12. Stool tests indicated an elastase-1 level of 80 μg/mL. The analysis of ascitic fluid demonstrated a WBC count of 54 × 106/L and a serum-ascites albumin gradient greater than 1.1 g/dL. All viral hepatitis-related indicators were negative, as were the autoimmune disease-related tests.

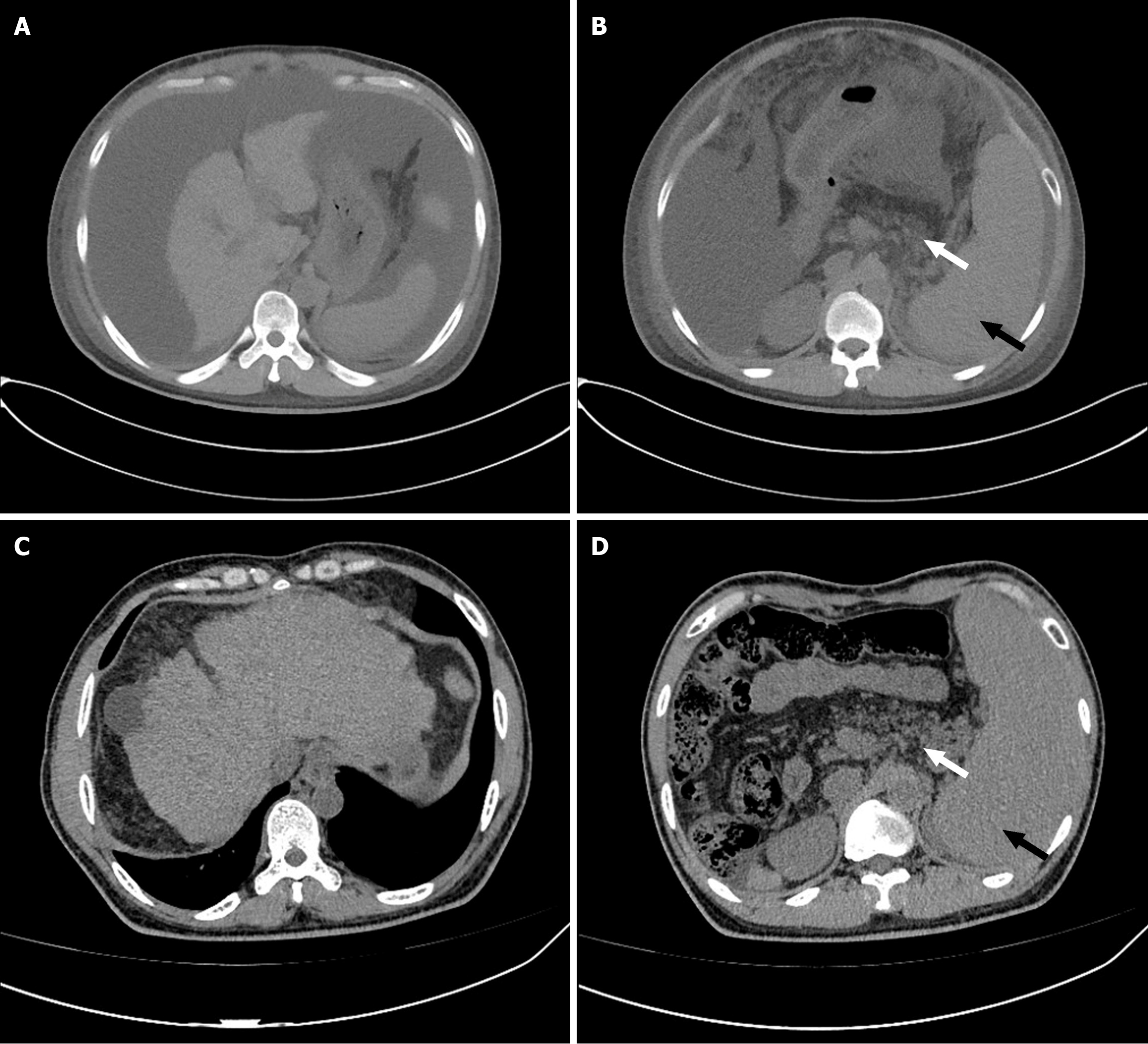

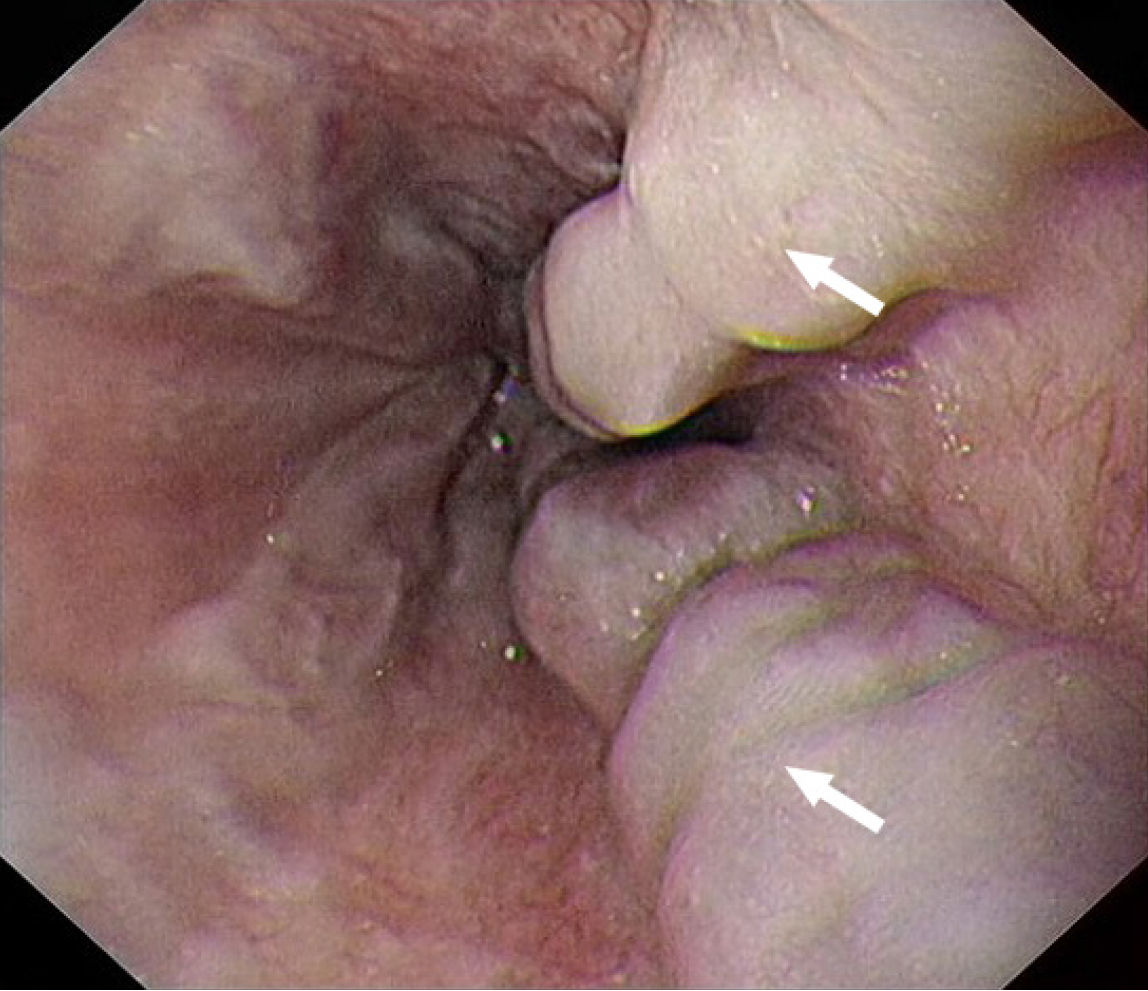

An abdominal computed tomography scan revealed the presence of liver cirrhosis, splenomegaly, and pancreatic fat infiltration, along with a significant accumulation of ascites (findings before and after treatment are shown in Figure 1). Gastroscopy indicated the presence of esophageal varices (Figure 2). Due to the patient's severe thrombocytopenia, there was a high risk of bleeding associated with a liver biopsy, thus preventing the successful acquisition of a pathological liver tissue sample.

The patient's condition concurrently affected both the liver and pancreas. A thorough evaluation of the patient's medical history, laboratory tests, and imaging findings allowed the exclusion of common causes of cirrhosis. Genetic testing identified mutations in the Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome (SBDS) gene [NM_016038: c.184A>T (p.Lys62) and c.258+2T>C], thereby confirming a diagnosis of cirrhosis attributable to SDS.

After correction of hypoproteinemia and administration of diuretic treatment, the patient’s ascites subsided. Oral carvedilol was administered to lower portal hypertension. However, the patient did not undergo further surgical intervention to address hypersplenism and prevent esophageal variceal bleeding.

During follow-up, the patient's nutritional status improved following the resolution of ascites. The use of Likoujun to ameliorate leukopenia and Ampeptide for thrombocytopenia resulted in peripheral blood WBC counts fluctuating between 1.6 × 109/L and 2.5 × 109/L, platelet counts between 20 × 109/L and 42 × 109/L, and hemoglobin levels between 80 g/L and 95 g/L. The patient did not undergo further surgical intervention for hypersplenism or esophageal variceal bleeding prevention and has had no recurrence of ascites to date.

SDS is a rare genetic disorder caused by mutations in the SBDS, DnaJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member C21, elongation factor-like 1 (EFL1), and signal recognition particle 54 genes, leading to damage to multiple organs[2-5]. The primary clinical features of SDS include skeletal abnormalities, neutropenia, and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. In addition to the pancreas and bones, the liver is frequently affected by SDS[1,6]. Most patients exhibit symptoms of the disease in infancy; however, some cases may arise during adolescence or even adulthood[7,8]. Ginzberg et al[9] reported that among 80 SDS patients, 63% experienced liver complications, primarily characterized by abnormal liver function, typically presenting as mild to moderate elevations in ALT, AST, and total bile acid levels, while alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, and TBIL levels were mostly normal. SDS is more prevalent in children under the age of 3 years. Hepatomegaly is a significant manifestation, occurring in 15%-85% of affected children[9,10]. The liver pathology observed in SDS patients predominantly exhibits inflammation, steatosis, and fibrosis, with lymphocytic infiltration around the portal areas, while pseudolobule formation is relatively rare[11-14]. The overall prognosis for SDS-related liver disease is favorable, with most patients experiencing resolution or a return to normal liver function during childhood. However, some children may develop complications such as cirrhosis and portal hypertension[8]. There are limited reports on liver diseases in adult SDS patients. Zhu et al[15] described a case of EFL1-related SDS in an adult patient who presented with liver fibrosis. Currently, there is no specific treatment for SDS-related liver disease, and management primarily focuses on symptomatic treatment. Regular monitoring of liver function and imaging of the liver and spleen are essential to assess whether liver damage continues to progress.

Liver cirrhosis-induced portal hypertension and gastrointestinal symptoms can easily obscure the clinical manifestations of SDS, such as neutropenia and pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, thereby delaying the diagnosis of SDS. This case suggests that for patients with unexplained cirrhosis and pancreatic fat infiltration, whole exome sequencing should be employed to further investigate the possibility of SDS. Furthermore, it is essential to reassess the prognosis of SDS-associated liver disease. While most SDS-related liver conditions tend to improve with age and generally have a favorable prognosis, some patients may experience a progressively deteriorating course, potentially leading to cirrhosis in adulthood. Therefore, it is advisable to implement long-term follow-up observations for patients with SDS-related liver disease to determine whether there is a persistent progression of potential liver damage, thereby preventing adverse outcomes.

The impact of SDS on adult liver function should be re-evaluated. In patients who present with both liver cirrhosis and pancreatic fat infiltration, and the etiology of the liver cirrhosis remains unexplained by common causes, it is advisable to conduct exon testing to exclude the possibility of SDS.

| 1. | Dror Y, Donadieu J, Koglmeier J, Dodge J, Toiviainen-Salo S, Makitie O, Kerr E, Zeidler C, Shimamura A, Shah N, Cipolli M, Kuijpers T, Durie P, Rommens J, Siderius L, Liu JM. Draft consensus guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1242:40-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dhanraj S, Matveev A, Li H, Lauhasurayotin S, Jardine L, Cada M, Zlateska B, Tailor CS, Zhou J, Mendoza-Londono R, Vincent A, Durie PR, Scherer SW, Rommens JM, Heon E, Dror Y. Biallelic mutations in DNAJC21 cause Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Blood. 2017;129:1557-1562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tan S, Kermasson L, Hoslin A, Jaako P, Faille A, Acevedo-Arozena A, Lengline E, Ranta D, Poirée M, Fenneteau O, Ducou le Pointe H, Fumagalli S, Beaupain B, Nitschké P, Bôle-Feysot C, de Villartay JP, Bellanné-Chantelot C, Donadieu J, Kannengiesser C, Warren AJ, Revy P. EFL1 mutations impair eIF6 release to cause Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Blood. 2019;134:277-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bellanné-Chantelot C, Schmaltz-Panneau B, Marty C, Fenneteau O, Callebaut I, Clauin S, Docet A, Damaj GL, Leblanc T, Pellier I, Stoven C, Souquere S, Antony-Debré I, Beaupain B, Aladjidi N, Barlogis V, Bauduer F, Bensaid P, Boespflug-Tanguy O, Berger C, Bertrand Y, Carausu L, Fieschi C, Galambrun C, Schmidt A, Journel H, Mazingue F, Nelken B, Quah TC, Oksenhendler E, Ouachée M, Pasquet M, Saada V, Suarez F, Pierron G, Vainchenker W, Plo I, Donadieu J. Mutations in the SRP54 gene cause severe congenital neutropenia as well as Shwachman-Diamond-like syndrome. Blood. 2018;132:1318-1331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Boocock GR, Morrison JA, Popovic M, Richards N, Ellis L, Durie PR, Rommens JM. Mutations in SBDS are associated with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:97-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 553] [Cited by in RCA: 548] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kawashima N, Oyarbide U, Cipolli M, Bezzerri V, Corey SJ. Shwachman-Diamond syndromes: clinical, genetic, and biochemical insights from the rare variants. Haematologica. 2023;108:2594-2605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Toiviainen-Salo S, Durie PR, Numminen K, Heikkilä P, Marttinen E, Savilahti E, Mäkitie O. The natural history of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome-associated liver disease from childhood to adulthood. J Pediatr. 2009;155:807-811.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Furutani E, Liu S, Galvin A, Steltz S, Malsch MM, Loveless SK, Mount L, Larson JH, Queenan K, Bertuch AA, Fleming MD, Gansner JM, Geddis AE, Hanna R, Keel SB, Lau BW, Lipton JM, Lorsbach R, Nakano TA, Vlachos A, Wang WC, Davies SM, Weller E, Myers KC, Shimamura A. Hematologic complications with age in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Blood Adv. 2022;6:297-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ginzberg H, Shin J, Ellis L, Morrison J, Ip W, Dror Y, Freedman M, Heitlinger LA, Belt MA, Corey M, Rommens JM, Durie PR. Shwachman syndrome: phenotypic manifestations of sibling sets and isolated cases in a large patient cohort are similar. J Pediatr. 1999;135:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Cipolli M, D'Orazio C, Delmarco A, Marchesini C, Miano A, Mastella G. Shwachman's syndrome: pathomorphosis and long-term outcome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;29:265-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Lawal OS, Mathur N, Eapi S, Chowdhury R, Malik BH. Liver and Cardiac Involvement in Shwachman-Diamond Syndrome: A Literature Review. Cureus. 2020;12:e6676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Camacho SM, McLoughlin L, Nowicki MJ. Cirrhosis complicating Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:1456-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Schaballie H, Renard M, Vermylen C, Scheers I, Revencu N, Regal L, Cassiman D, Sevenants L, Hoffman I, Corveleyn A, Bordon V, Haerynck F, Allegaert K, De Boeck K, Roskams T, Boeckx N, Bossuyt X, Meyts I. Misdiagnosis as asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy and CMV-associated haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:613-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bucciol G, Cassiman D, Roskams T, Renard M, Hoffman I, Witters P, Schrijvers R, Schaballie H, Bosch B, Putti MC, Gheysens O, Knops N, Gewillig M, Mekahli D, Pirenne J, Meyts I. Liver transplantation for very severe hepatopulmonary syndrome due to vitamin A-induced chronic liver disease in a patient with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhu B, Guo Y, Lv S, Ling X, You S. Hepatic phenotypes of EFL1-related Shwachman-Diamond syndrome in a biopsy-validated study. J Hepatol. 2024;81:e102-e104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |