Published online May 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i5.105890

Revised: April 4, 2025

Accepted: April 18, 2025

Published online: May 27, 2025

Processing time: 107 Days and 2.5 Hours

Laparoscopic hepatectomy (LH) has been applied in the treatment of hepatolithiasisa in patients with a history of biliary surgery and has already achieved good clinical outcomes. However, reoperative LH (rLH) includes multiple procedures, and the no studies have examined the clinical value of individual laparoscopic procedures.

To evaluate the safety and feasibility of each rLH procedure for hepatolithiasisa in patients with a history of biliary surgery.

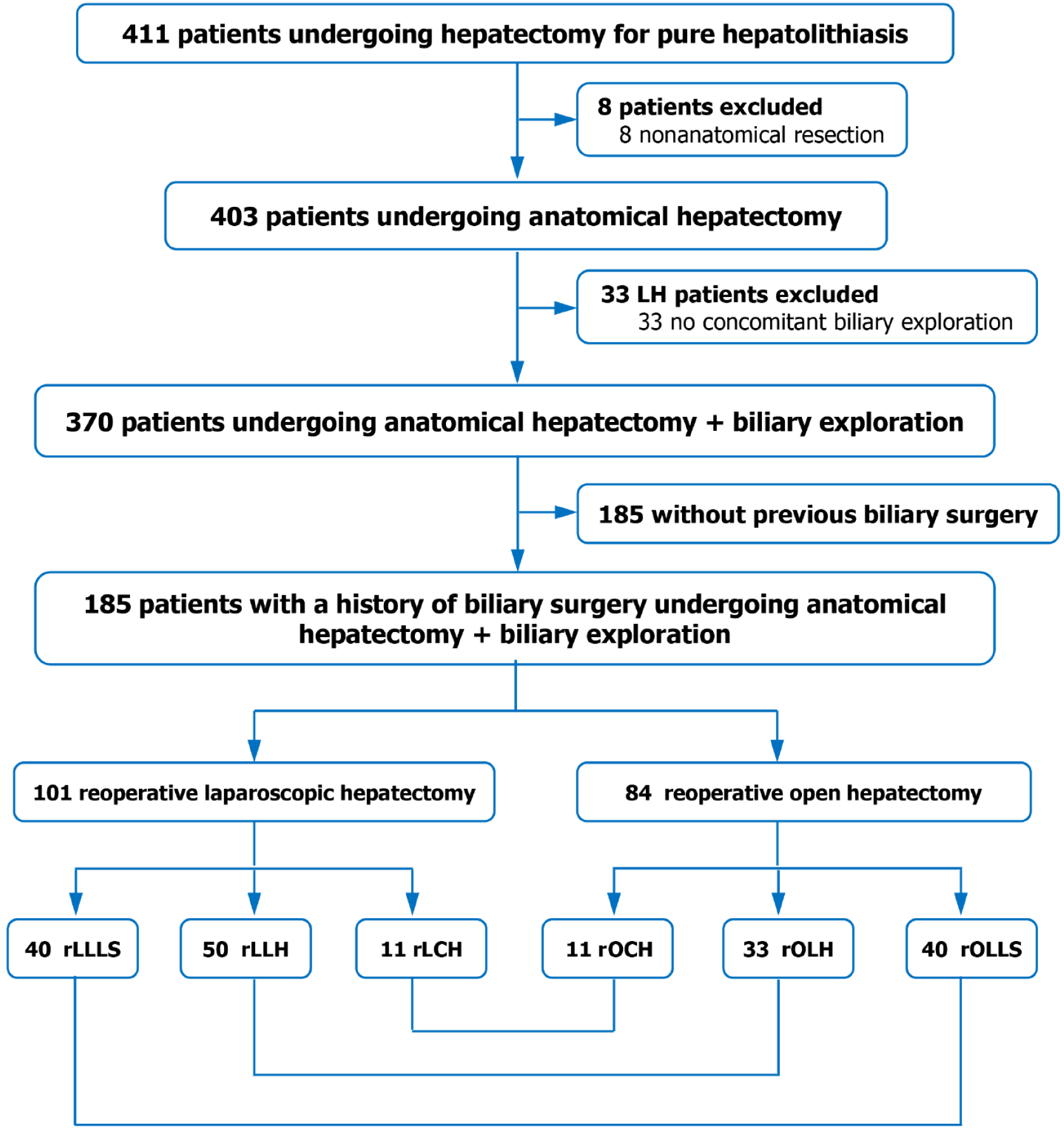

Patients with previous biliary surgery who underwent reoperative hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis were studied. Liver resection procedures were divided into three categories: (1) Laparoscopic/open left lateral sectionectomy [reoperative laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy (rLLLS)/reoperative open left lateral sectionectomy (rOLLS)]; (2) Laparoscopic/open left hemihepatectomy [reope

A total of 185 patients were studied, including 101 rLH patients (40 rLLLS, 50 rLLH, and 11 rLCH) and 84 reo

The rLH is safe for hepatolithiasis patients with a history of biliary surgery. The rLLLS and rLLH can be re

Core Tip: This study aimed to evaluate the safety and feasibility of three types of reoperative laparoscopic hepatectomy procedures in patientsfor with hepatolithiasis and a history of biliary surgery. Among the three procedures, reoperative laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy (rLLLS) had the most favorable clinical outcomes, followed by reoperative laparoscopic left hemihepatectomy (rLLH). However, reoperative laparoscopic complex hepatectomy (rLCH) had the lowest clinical value. The majority of clinical outcomes in rLLLS and rLLH patients were either superior or equivalent to those in the corresponding open procedures, while rLCH did not offer any advantages over the corresponding open surgery. Therefore, rLLLS and rLLH are recommended for these patients, while rLCH should be used with caution.

- Citation: Zhang WJ, Chen G, Dai DF, Chen XP. Not all reoperative laparoscopic liver resection procedures are feasible for hepatolithiasis patients with a history of biliary surgery. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(5): 105890

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i5/105890.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i5.105890

Hepatolithiasis is common in Southeast Asia but rare in Western countries[1]. Patients with hepatolithiasis often have a history of biliary surgery. A survey from Japan showed that the proportion of patients who underwent previous biliary surgery is as high as 61%[2]. When the patients develop liver parenchymal lesions such as liver fibrosis, liver atrophy, liver abscesses, and even cholangiocarcinoma, hepatectomy is still the most effective treatment method in addition to liver transplantation, as it can simultaneously remove intrahepatic stones and concomitant liver lesions. Open hepa

With the development of minimally invasive techniques and devices, laparoscopic hepatectomy (LH) has been applied in the treatment of patients with hepatolithiasis and a history of biliary or upper abdominal surgery in the last 20 years and has already achieved good clinical outcomes[4,5]. However, reoperative LH (rLH) includes multiple procedures, and the above studies did not examine individual laparoscopic procedures. Different procedures have their own clinical and technical characteristics; therefore, their clinical values may vary. It remains unclear whether each rLH procedure is suitable for patients with hepatolithiasis and a history of biliary surgery. This is an important clinical issue that should not be ignored by hepatobiliary surgeons. If applied properly, the procedure alleviates pain in patients and promotes recovery. Otherwise, it may increase the surgical risk and even endanger the patient's life. Therefore, it is essential to perform a clinical evaluation of each rLH procedure.

This study aimed to evaluate the safety and feasibility of different rLH procedures for hepatolithiasis patients with a history of biliary surgery using clinical comparisons and subgroup analysis.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The First Affiliated Hospital (Yijishan Hospital) of Wannan Medical College (No. [2022]106) on 3 January 2023, performed at the same institution, and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. This study was part of a clinical trial (www.chictr.org.cn, ChiCTR2300072545). Informed consent forms were signed by all study subjects and investigators of the study. The study design and preparation of the original manuscript were performed according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement[6].

Patients with a history of biliary surgery who underwent liver resection for hepatolithiasis between January 2015 and December 2022 were included in the study. Their clinical data of these patients were collected. Left lateral sectionectomy and left hemihepatectomy were the two most commonly performed surgical procedures. Other procedures were less commonly used and were collectively called complex liver resections, which included right posterior sectionectomy, right hemihepatectomy, left lateral sectionectomy in combination with right posterior sectionectomy, and hepatectomy with caudal lobe resection. These procedures are relatively complex, time-consuming, and associated with considerable risks. Based on the above classification, we categorized all procedures into three types: (1) Laparoscopic or open left lateral sectionectomy [reoperative laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy (rLLLS) or reoperative open left lateral sectionectomy (rOLLS)]; (2) Laparoscopic or open left hemihepatectomy [reoperative laparoscopic left hemihepatectomy (rLLH) or reoperative open left hemihepatectomy (rOLH)]; and (3) Laparoscopic or open complex hepatectomy [reoperative laparoscopic complex hepatectomy (rLCH) or reoperative open complex hepatectomy (rOCH)]. The clinical outcomes of the three types of reoperative laparoscopic procedures ( rLLLS, rLLH, and rLCH) were compared to explore the differences in the safety and feasibility. Each rLH procedure was then compared with the corresponding open surgery procedure to evaluate its relative clinical value.

The following inclusion criteria were used for patient selection: (1) Multiple stones in the intrahepatic bile duct identified by ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); (2) A history of biliary surgery before hepatectomy regardless of whether it is a recurrent or residual stone; (3) With or without concomitant benign liver lesions at the same site as most stones, including liver atrophy, chronic liver abscess, intrahepatic bile duct stenosis or dilation, hepatic hemangioma, papilloma, etc.; (4) Child-Pugh class A or B and serum albumin > 30 g/L; (5) Anatomical hepatectomy followed by a biliary exploration as the main treatment for hepatolithiasis; and (6) Typical histological changes of hepatolithiasis verified by postoperative pathological examination.

The exclusion criteria included: (1) Secondary intrahepatic stones due to anastomotic stenosis of a previous biliary-enteric anastomosis; (2) Stones combined with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) or other hepatobiliary malignancy; (3) Non-anatomical hepatectomy; (4) Hepatectomy without biliary exploration (as all OH patients underwent con

Following control of cholangitis and improvement of liver function, the patient underwent elective liver resection under general anesthesia with tracheal intubation. For OH patients, an oblique incision or an inverted L-shaped incision of the right upper abdomen was usually made. When the liver and hepatoduodenal ligaments were adequately mobilized, liver resection and bile duct exploration were performed according to previous reports[4,7].

All rLHs were performed by senior surgeons with more than three years of experience in laparoscopic liver resection. Patients were placed in the supine position with legs apart. A five-hole method was employed. The Veress needle was inserted directly at the lower edge of the umbilicus in patients with a history of laparoscopic cholecystectomy or open surgery whose previous incision site was more than 3 cm from the umbilicus. If the previous incision site was less than 3 cm away from the umbilicus, an open Hasson technique was applied to enter to the peritoneal cavity[8]. After CO2 artificial pneumoperitoneum was established, a 30-degree camera (Karl Storz Endoscopy, Tuttlingen, Germany) was inserted into the abdomen to observe any visible organs or adhesion. The first operating port was made in the nona

Postoperative monitoring, drug administration, drainage tube management, and follow-up were performed according to a previously published report[7]. The final follow-up date was June 30, 2023.

Intraoperative outcomes included the choice of hepatic blood inflow occlusion, operation duration, estimated blood loss, blood transfusion, and conversion to OH. The short-term outcomes were postoperative intensive care unit (ICU) stay, postoperative hospital stay, 90-day complications, 90-day major complications, re-intervention for complications, initial stone clearance, re-treatment for residual stones, final calculi clearance, readmission, and 90-day mortality. Long-term outcomes included stone recurrence, late complications, secondary ICC, and late death.

Baseline variables included gender, age, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists score, obstructive jaundice, benign liver lesions, number of previous surgeries, types of previous procedure, types of previous approach, and interval between the last two surgeries. Previous biliary surgeries, including cholecystectomy, biliary exploration, and liver resection, were performed using an open or laparoscopic approach. Major complications were defined as Clavien-Dindo grade III or higher[9], with the most severe complication accounting for the complication rate. Short-term re-interventions were defined as endoscopic, radiological, or surgical treatments within 90 days after surgery due to complications. Readmission meant a second hospitalization within 3 months after surgery due to complications or residual stones. Residual stones were defined as the presence of stones in the intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile duct detected by postoperative T-tube cholangiography, ultrasonography, CT,or MRI within 3 months after surgery[10]. Re-treatment for residual stones included subsequent choledochoscopy or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Late complications were limited to uncontrolled or new-onset events that occurred more than 3 months after reoperation. Late death was defined as death due to late complications or secondary ICC.

Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as mean (SD) and nonnormally distributed variables as median (interquartile ranges). Categorical variables were reported as absolute number (percentage). Missing data were imputed using a regularized expectation maximization algorithm. One-way analysis of variance, Kruskal-Wallis test, and χ2 test were performed to analyze the differences among the three rLHs, and the P values of the multiple comparisons were adjusted with the Bonferroni correction to control Type I errors. Comparisons between two subgroups were analyzed using the Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney test, and χ2 test. All analyses were performed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences statistics (version 26.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States). A 2-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 447 patients underwent hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. After exclusion, 185 patients with a history of biliary surgery who underwent anatomical liver resection combined with biliary exploration for pure hepatolithiasis were identified, including 101 patients who underwent rLH and 84 underwent rOH (Figure 1). The rLH patients included 40 cases of rLLLS, 50 of rLLH, and 11 of rLCH, while rOH patients included 40 of rOLLS, 33 of rOLH, and 11 of rOCH. There were no missing preoperative data, except for BMI [69 (37.3%)]. Data imputation led to completion of the variables. There were no significant differences in the demographic characteristics between the rLLLS, rLLH, and rLCH groups (all P > 0.05) (Table 1). There were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between each pair of laparoscopic and open reoperations in the three subgroups (rLLLS/rOLLS, rLLH/rOLH, and rLCH/rOCH) (Supplementary Tables 1, 2, and 3).

| Characteristic | Reoperative laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy (n = 40) | Reoperative laparoscopic left hemihepatectomy (n = 50) | Reoperative laparoscopic complex hepatectomy (n = 11) | χ²/F value | P value |

| Male | 9 (22.5) | 16 (32.0) | 4 (36.4) | 1.333 | 0.5141 |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 62.3 (11.5) | 61.8 (7.8) | 60.0 (7.7) | 0.261 | 0.7712 |

| Body mass index > 21.5 kg/m2 | 18 (45.0) | 25 (50.0) | 6 (54.5 ) | 0.402 | 0.8181 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists score 2-3 | 21 (52.5) | 19 (38.0) | 5 (45.5) | 1.895 | 0.3881 |

| Obstructive jaundice | 6 (15.0) | 11 (22.0) | 2 (18.2) | 0.716 | 0.6991 |

| Benign liver lesions | 32 (80.0) | 43 (86.0) | 9 (81.8) | 0.588 | 0.7451 |

| Number of previous surgeries > 2 | 2 (5.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A3 | 0.706 |

| Types of previous procedure | N/A3 | 0.250 | |||

| cholecystectomy | 29 (72.5) | 28 (56.0) | 9 (81.8) | ||

| Choledochotomy with exploration | 11 (27.5) | 19 (38.0) | 2 (18.0) | ||

| Hepatectomy | 0 (0.0) | 3 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Types of previous approach | N/A3 | 0.789 | |||

| Open surgery | 30 (75.0) | 40 (80.0) | 9 (81.8) | ||

| Laparoscopic surgery | 9 (22.5) | 7 (14.0) | 2 (18.0) | ||

| Unclear | 1 (2.5) | 3 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Interval between last two surgeries | N/A3 | 0.608 | |||

| ≤ 2 years | 3 (7.5) | 8 (16.0) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| > 2 years | 30 (75.0) | 37 (74.0) | 8 (72.7) | ||

| Unknown time-interval | 7 (17.5) | 5 (10.0) | 1 (9.1) |

The clinical outcomes of the three types of laparoscopic reoperations are shown in Table 2. There were significant differences in the use of selective hepatic blood flow occlusion (20.0% vs 94.0% vs 63.6%, P < 0.001), median operation duration (240.0 minutes vs 325.0 minutes vs 350.0 minutes, P = 0.001), blood transfusion rate (10.0% vs 22.0% vs 54.5%, P = 0.005), and postoperative ICU stay rate (12.5% vs 20.0% vs 63.6%, P = 0.001) among the rLLLS, rLLH, and rLCH groups. The rLLLS group required the shortest operation duration and the lowest blood transfusion rate (both P < 0.05). In contrast, the rLCH group had the longest operation duration, most blood transfusions, and highest ICU stay rate (all P < 0.05). Surprisingly, the laparoscopic conversion rate of rLCH was still significantly higher than that of rLLLS (36.4% vs 7.5%, P < 0.05), although no difference was found between the three groups. There were no differences in any of the postoperative outcomes, except for postoperative ICU stay.

| Characteristic | Reoperative laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy (n = 40) | Reoperative laparoscopic left hemihepatectomy (n = 50) | Reoperative laparoscopic complex hepatectomy (n = 11) | χ²/H value | P value |

| Selective hepatic blood flow occlusion | 8/40 (20.0) | 47/50 (94.0)6 | 7/11 (63.6)6,7 | 51.364 | < 0.0011 |

| Operation duration, median (IQR), minute | 240.0 (196.3-322.5) | 325.0 (254.5-387.8)6 | 350.0 (295.0-460.0)6 | 14.508 | 0.0012 |

| Blood loss, median (IQR), mL | 200.0 (75.0-281.2) | 200.0 (100.0-400.0) | 400.0 (200.0-800.0) | 5.837 | 0.0542 |

| Blood transfusion | 4/40 (10.0) | 11/50 (22.0)6 | 6/11 (54.5)6 | 10.483 | 0.0051 |

| Conversion to open surgery | 3/40 (7.5) | 8/50 (16.0) | 4/11 (36.4)6 | 5.787 | 0.0551 |

| Postoperative intensive care unit stay | 5/40 (12.5) | 10/50 (20.0) | 7/11 (63.6)6,7 | 13.426 | 0.0011 |

| Postoperative stay, median (IQR), days | 8.0 (6.0-10.0) | 8.0 (7.0-12.3) | 10.0 (7.0-13.0) | 2.211 | 0.3312 |

| Early complications within 90 days | 17/40 (42.5) | 27/50 (54.0) | 7/11 (63.6) | 2.028 | 0.3631 |

| Major complications within 90 days | 2/40 (5.0) | 3/50 (6.0) | 0/11 (0.0) | N/A3 | 1.000 |

| Reinterventions within 90 days | 2/40 (5.0) | 3/50 (6.0) | 0/11 (0.0) | N/A3 | 1.000 |

| Readmission within 90 days | 6/40 (15.0) | 10/50 (20.0) | 3/11 (27.3) | 0.942 | 0.6241 |

| 90-day mortality | 0/40 (0.0) | 0/50 (0.0) | 0/11 (0.0) | - | - |

| Initial stone clearance4 | 33/40 (82.5) | 36/48 (75.0) | 8/11 (72.7) | 0.893 | 0.6401 |

| Re-treatment for residual stones4 | 2/40 (5.0) | 6/48 (12.5) | 1/11 (9.1) | N/A3 | 0.412 |

| Final stone clearance4 | 34/40 (85.0) | 39/48 (81.3) | 8/11 (72.7) | 0.894 | 0.6401 |

| Stone recurrence5 | 2/34 (5.9) | 2/39 (5.1) | 0/8 (0.0) | N/A3 | 1.000 |

| Late complications4 | 1/40 (2.5) | 3/48 (6.3) | 1/11 (9.1) | N/A3 | 0.411 |

| Late major complications4 | 0/40 (0.0) | 1/48 (2.1) | 0/11 (0.0) | N/A3 | 1.000 |

| Secondary ICC4 | 1/40 (2.5) | 0/48 (0.0) | 0/11 (0.0) | N/A3 | 0.515 |

| Late death due to complications or ICC4 | 1/40 (2.5) | 0/48 (0.0) | 0/11 (0.0) | N/A3 | 0.515 |

To further understand the safety and feasibility of different reoperative laparoscopic procedures for hepatolithiasis, we compared them with corresponding open procedures. The clinical outcomes in the rLLLS/rOLLS subgroups are shown in Table 3. The median operation duration in the rLLLS subgroup was longer than that in the rOLLS subgroup (240.0 minutes vs 200.0 minutes, P = 0.002). However, the blood transfusion rate (10.0% vs 30.0%, P = 0.025), median postoperative hospital stay (8.0 days vs 13.0 days, P = 0.001), and stone recurrence rate (5.9% vs 28.1%, P = 0.015) in the rLLLS subgroup were lower or shorter than those in the rOLLS subgroup. No differences were found in the other outcomes.

| Clinical outcomes | Reoperative open left lateral sectionectomy (n = 40) | Reoperative laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy (n = 40) | χ²/Z value | P value |

| Selective hepatic blood flow occlusion | 5/40 (12.5) | 8/40 (20.0) | 0.827 | 0.3631 |

| Operation duration, median (IQR), minute | 200.0 (180.0-240.0) | 240.0 (196.3-322.5) | -3.073 | 0.0022 |

| Blood loss, median (IQR), mL | 200.0 (81.3-300.0) | 200.0 (75.0-281.2) | -0.743 | 0.4572 |

| Blood transfusion | 12/40 (30.0) | 4/40 (10.0) | 5.000 | 0.0251 |

| Conversion to open surgery | - | 3/40 (7.5) | - | - |

| Postoperative intensive care unit stay | 5/40 (12.5) | 5/40 (12.5) | 0.000 | 1.0001 |

| Postoperative hospital stay, median (IQR), days | 10.0 (8.0-17.0) | 8.0 (6.0-10.0) | -3.332 | 0.0012 |

| Early complications within 90 days | 16/40 (40.0) | 17/40 (42.5) | 0.052 | 0.8201 |

| Major complications within 90 days | 1/40 (2.5) | 2/40 (5.0) | N/A3 | 1.000 |

| Reinterventions within 90 days | 1/40 (2.5) | 2/40 (5.0) | N/A3 | 1.000 |

| Readmission within 90 days | 5/40 (12.5) | 6/40 (15.0) | 0.105 | 0.7451 |

| 90-day mortality | 0/40 (0.0) | 0/40 (0.0) | - | - |

| Initial stone clearance rate4 | 29/39 (74.4) | 33/40 (82.5) | 0.775 | 0.3791 |

| Re-treatment of residual stones4 | 4/39 (10.3) | 2/40 (5.0) | N/A3 | 0.432 |

| Final stone clearance rate4 | 32/39 (85.0) | 34/40 (85.0) | 0.125 | 0.7241 |

| Stone recurrence5 | 9/32(28.1 ) | 2/34 (5.9) | 5.872 | 0.0151 |

| Late complications4 | 1/39 (2.6) | 1/40 (2.5) | N/A3 | 1.000 |

| Late major complications4 | 1/39 (2.6) | 0/40 (0.0) | N/A3 | 0.494 |

| Secondary ICC4 | 4/39 (10.3) | 1/40 (2.5) | N/A3 | 0.201 |

| Late death due to complications or ICC4 | 4/39 (10.3) | 1/40 (2.5) | N/A3 | 0.201 |

The outcomes in the rLLH/rOLH subgroups are shown in Table 4. There was no significant difference in the transfusion rate between the two subgroups. The remaining outcomes in the rLLH/rOLH subgroups were similar to those in the rLLS/rOLLS subgroups. Unlike the rLLH/rOLH and rLLLS/rOLLS subgroups, there were no differences in all outcomes between the rLCH/rOCH subgroups (Supplementary Table 4); however, the rLCH subgroup had a high conversion rate (36.4%).

| Clinical outcomes | Reoperative open left hemihepatectomy (n = 33) | Reoperative laparoscopic left hemihepatectomy (n = 50) | χ²/t/Z value | P value |

| Selective hepatic blood flow occlusion | 29/33 (87.9) | 47/50 (94.0) | 0.956 | 0.3261 |

| Operation duration, mean (SD), minute | 244.7 (84.7) | 318.9 (88.5) | -3.800 | 0.0002 |

| Blood loss, median (IQR), mL | 235.7 (150.0-400.0) | 200.0 (100.0-400.0) | -1.411 | 0.1583 |

| Blood transfusion | 13/33 (39.4) | 11/50 (22.0) | 2.926 | 0.0871 |

| Conversion to open surgery | - | 8/50 (16.0) | - | - |

| Postoperative intensive care unit stay | 5/33 (15.2) | 10/50 (20.0) | 0.316 | 0.5741 |

| Postoperative hospital stay, median (IQR), days | 13.0 (8.0-21.0) | 8.0 (7.0-12.3) | -3.237 | 0.0013 |

| Early complications within 90 days | 21/33 (63.6) | 27/50 (54.0) | 0.757 | 0.3841 |

| Major complications within 90 days | 1/33 (3.0) | 3/50 (6.0) | N/A4 | 1.000 |

| Reinterventions within 90 days | 1/33 (3.0) | 3/50 (6.0) | N/A4 | 1.000 |

| Readmission within 90 days | 6/33 (18.2) | 10/50 (20.0) | 0.042 | 0.8371 |

| 90-day mortality | 0/33 (0.0) | 0/50 (0.0) | - | - |

| Initial stone clearance rate5 | 25/32 (78.1) | 36/48 (75.0) | 0.104 | 0.7481 |

| Re-treatment of residual stones5 | 4/32 (12.5) | 6/48 (12.5) | N/A3 | 1.000 |

| Final stone clearance rate5 | 26/32 (81.3) | 39/48 (81.3) | 0.000 | 1.0001 |

| Stone recurrence6 | 8/26(30.8 ) | 2/39 (5.1) | N/A4 | 0.011 |

| Late complications5 | 4/32 (12.5) | 3/48 (6.3) | N/A4 | 0.429 |

| Late major complications5 | 2/32 (6.3) | 1/48 (2.1) | N/A4 | 0.561 |

| Secondary ICC5 | 0/32 (0.0) | 0/48 (0.0) | - | - |

| Late death due to complications or ICC5 | 1/32 (3.1) | 0/48 (0.0) | N/A4 | 0.400 |

This multi-cohort study systematically analyzed the clinical differences between multiple rLH procedures and their relative advantages over rOH for pure hepatolithiasis in patients with a history of biliary surgery. Of the three types of rLH, rLLLS patients had the best clinical outcomes, followed by rLLH patients, whereas rLCH showed the lowest clinical value. Most clinical outcomes in the rLLLS and rLLH subgroups were better than or equal to those undergoing the corresponding rOH procedures, while rLCH had no advantage over rOCH with a high conversion rate. To our knowledge, this study is the first to systematically investigate the clinical characteristics of each rLH procedure for hepatolithiasis in patients with a history of biliary surgery. In the absence of international guidelines, our study provides meaningful clinical evidence for the rational application of each rLH procedure for recurrent or residual intrahepatic stones.

To understand the differences in the safety and feasibility of different rLH procedures, we first compared the clinical outcomes of the three types of rLH procedures and found that the differences were mainly related to intraoperative indicators and postoperative ICU stay. The rLLLS had the shortest operation duration and the lowest blood transfusion rate. Selective hepatic blood flow occlusion is most commonly performed in rLLH patients. However, the rLCH group had the longest median operation duration, most blood transfusions, and the highest laparoscopic conversion rate. No significant differences were found in other clinical outcomes, and no patients in any of the groups died within 90 days post-surgery. These results suggest that all three procedures are safe for hepatolithiasis patients with a history of biliary surgery, with rLLLS having the greatest clinical advantage and rLCH having relatively low feasibility. LLLS has been recognized as the gold standard for the treatment of liver cancer and some benign liver lesions due to its good clinical outcome and cost-effectiveness[11-13]. Based on the results of this study, we also believe that rLLLS is the preferred option for hepatolithiasis patients with a history of biliary surgery if left lateral sectionectomy is required.

To further evaluate the safety and feasibility of each rLH procedure, we compared each procedure with the corresponding open reoperation, as rOH can still be performed in almost every patient with a success rate of nearly 100%[3]. As a result, most clinical outcomes of rLLLS and rLLH were equal to or better than those of their corresponding rOH, except for prolonged operation duration. Laparoscopic repeat hepatectomy has been reported to have a similar[14] or shorter[15-17] operative time than open repeat liver resection for recurrent and metastatic liver cancers. However, due to previous surgery, multiple stones, dense perihepatic adhesions, and severe inflammation, rLH is more difficult to perform than rOH for hepatolithiasis patients with a history of biliary surgery. In patients with recurrent and metastatic liver tumors, this inflammation does not exist, but can seriously affect the surgical process of hepatolithiasis patients with a history of biliary surgery. Therefore, rLLLS and rLLH required longer operation durations in this study. As reported in the literature[4,5], rLLLS and rLLH did not significantly reduce the intraoperative blood loss in this study. However, rLLLS and rLLH have significant advantages over their corresponding open procedures in reducing intraoperative blood transfusion, shortening postoperative hospital stay, and decreasing stone recurrence. The complication and mortality rates in the two subgroups were the same or similar to their corresponding open surgeries. These results suggest that rLLLS and rLLH are highly safe and feasible for hepatolithiasis patients with a history of biliary surgery.

Inexplicably, there was no difference in all clinical outcomes including operation duration and postoperative hospital stay between the rLCH and rOCH subgroups. The main reason for this is that both subgroups had relatively small sample sizes. Therefore, subgroup analysis did not show any advantages of rLCH. Furthermore, the rLCH subgroup had a high conversion rate (36.4%). In this study, rLCH is a general term for multiple technically demanding laparoscopic procedures that require specific skills, require patient selection, and carry a risk of bleeding and unsuccessful resection. Therefore, a high conversion rate is inevitable or understandable, which once again indicates that the feasibility of LCH is relatively low. From the perspective of safety and feasibility, rLCH and even rLLH should be performed by skilled surgeons in well-equipped medical centers.

This study has several limitations. First, owing to the retrospective study design, we do not know the reasons why surgeons choose rOH or rLH. Generally speaking, surgeons may choose patients with relatively mild liver lesions for laparoscopic surgery. Second, some information or data were lacking or incomplete, such as partial BMI and individual previous procedures. Expectation maximization imputation had to be performed for BMI in 37.3% of the 185 patients. The data processing may have caused bias. However, the differences between the two groups can be ignored as all P values were more than 0.05. Third, the sample sizes in the three groups were small, especially in the rLCH group. Therefore, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. In addition, reoperative laparoscopic liver resection should be limited to patients with a history of 1-2 biliary surgeries. For those with a history of multiple surgeries, laparoscopic surgery is no longer suitable due to safety and feasibility issues.

All three procedures are safe for hepatolithiasis patients with a history of biliary surgery. The rLLLS and rLLH can be recommended as their overall clinical efficacy is superior to or similar to their corresponding open surgery, while rLCH should be performed with caution due to its relatively low feasibility.

The authors thank all the patients who took part in this study and our colleagues in the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery of our hospital for their contributions to surgical procedures and patient management.

| 1. | García D, Marino C, Ferreira Coelho F, Rebolledo P, Achurra P, Marques Fonseca G, Kruger JAP, Viñuela E, Briceño E, Carneiro D'Albuquerque L, Jarufe N, Martinez JA, Herman P, Dib MJ. Liver resection for hepatolithiasis: A multicenter experience in Latin America. Surgery. 2023;173:299-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tazuma S, Nakanuma Y. Clinical features of hepatolithiasis: analyses of multicenter-based surveys in Japan. Lipids Health Dis. 2015;14:129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yang T, Lau WY, Lai EC, Yang LQ, Zhang J, Yang GS, Lu JH, Wu MC. Hepatectomy for bilateral primary hepatolithiasis: a cohort study. Ann Surg. 2010;251:84-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tian J, Li JW, Chen J, Fan YD, Bie P, Wang SG, Zheng SG. The safety and feasibility of reoperation for the treatment of hepatolithiasis by laparoscopic approach. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1315-1320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fan Y, Huang J, Xu L, Xu Q, Tang X, Zheng K, Hu W, Liu J, Wang J, Liu T, Liang B, Xiong H, Li W, Fu X, Fang L. Laparoscopic anatomical left hemihepatectomy guided by middle hepatic vein in the treatment of left hepatolithiasis with a history of upper abdominal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:9116-9124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5694] [Cited by in RCA: 6449] [Article Influence: 429.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (108)] |

| 7. | Chen XP, Zhang WJ, Cheng B, Yu YL, Peng JL, Bao SH, Tong CG, Zhao J. Clinical and economic comparison of laparoscopic versus open hepatectomy for primary hepatolithiasis: a propensity score-matched cohort study. Int J Surg. 2024;110:1896-1903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hasson HM. A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110:886-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 404] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24776] [Article Influence: 1179.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee TY, Chen YL, Chang HC, Chan CP, Kuo SJ. Outcomes of hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. World J Surg. 2007;31:479-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vanounou T, Steel JL, Nguyen KT, Tsung A, Marsh JW, Geller DA, Gamblin TC. Comparing the clinical and economic impact of laparoscopic versus open liver resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:998-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Macacari RL, Coelho FF, Bernardo WM, Kruger JAP, Jeismann VB, Fonseca GM, Cesconetto DM, Cecconello I, Herman P. Laparoscopic vs. open left lateral sectionectomy: An update meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg. 2019;61:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dokmak S, Raut V, Aussilhou B, Ftériche FS, Farges O, Sauvanet A, Belghiti J. Laparoscopic left lateral resection is the gold standard for benign liver lesions: a case-control study. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:183-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Miyama A, Morise Z, Aldrighetti L, Belli G, Ratti F, Cheung TT, Lo CM, Tanaka S, Kubo S, Okamura Y, Uesaka K, Monden K, Sadamori H, Hashida K, Kawamoto K, Gotohda N, Chen K, Kanazawa A, Takeda Y, Ohmura Y, Ueno M, Ogura T, Suh KS, Kato Y, Sugioka A, Belli A, Nitta H, Yasunaga M, Cherqui D, Halim NA, Laurent A, Kaneko H, Otsuka Y, Kim KH, Cho HD, Lin CC, Ome Y, Seyama Y, Troisi RI, Berardi G, Rotellar F, Wilson GC, Geller DA, Soubrane O, Yoh T, Kaizu T, Kumamoto Y, Han HS, Ekmekcigil E, Dagher I, Fuks D, Gayet B, Buell JF, Ciria R, Briceno J, O'Rourke N, Lewin J, Edwin B, Shinoda M, Abe Y, Hilal MA, Alzoubi M, Tanabe M, Wakabayashi G. Multicenter Propensity Score-Based Study of Laparoscopic Repeat Liver Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Subgroup Analysis of Cases with Tumors Far from Major Vessels. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:3187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Morise Z, Aldrighetti L, Belli G, Ratti F, Belli A, Cherqui D, Tanabe M, Wakabayashi G; ILLS-Tokyo Collaborator group. Laparoscopic repeat liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre propensity score-based study. Br J Surg. 2020;107:889-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shen Z, Cai J, Gao J, Zheng J, Tao L, Liang Y, Xu J, Liang X. Efficacy of laparoscopic repeat hepatectomy compared with open repeat hepatectomy: a single-center, propensity score matching study. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20:197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | van der Poel MJ, Barkhatov L, Fuks D, Berardi G, Cipriani F, Aljaiuossi A, Lainas P, Dagher I, D'Hondt M, Rotellar F, Besselink MG, Aldrighetti L, Troisi RI, Gayet B, Edwin B, Abu Hilal M. Multicentre propensity score-matched study of laparoscopic versus open repeat liver resection for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2019;106:783-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |