Published online Jan 27, 2023. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v15.i1.79

Peer-review started: September 22, 2022

First decision: October 17, 2022

Revised: October 25, 2022

Accepted: November 7, 2022

Article in press: November 7, 2022

Published online: January 27, 2023

Processing time: 116 Days and 4 Hours

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the leading cause of liver disease globally with an estimated prevalence of 25%, with the clinical and economic bur

To identify the outcomes of NVUGIB in NAFLD hospitalizations in the United States.

We utilized the National Inpatient Sample from 2016-2019 to identify all NVUGIB hospitalizations in the United States. This population was divided based on the presence and absence of NAFLD. Hospitalization characteristics, outcomes and complications were compared.

The total number of hospitalizations for NVUGIB was 799785, of which 6% were found to have NAFLD. NAFLD and GIB was, on average, more common in youn

NVUGIB in NAFLD hospitalizations had higher inpatient mortality, THC, and complications such as shock, acute respiratory failure, and acute liver failure compared to those without NAFLD.

Core Tip: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a growing problem. The national inpatient database was used to identify patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding who were categorized based on NAFLD status. Statistically significant differences were observed between the two cohorts with respect to mortality, utilization of healthcare resources and complications. We believe this will be beneficial for physicians in terms of predicting morbidity and prognosis in these patients.

- Citation: Soni A, Yekula A, Singh Y, Sood N, Dahiya DS, Bansal K, Abraham G. Influence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease on non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: A nationwide analysis. World J Hepatol 2023; 15(1): 79-88

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v15/i1/79.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v15.i1.79

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a common cause of chronic liver disease worldwide[1]. It has a disease spectrum ranging from hepatic steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, which may ultimately lead to liver cirrhosis[2]. Major risk factors for NAFLD include obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, and increasing age. The primary path

Upper GIB can be divided into 2 main categories, namely variceal and non-variceal upper GIB (NVUGIB). Variceal GIB is usually seen in patients with portal hypertension in a setting of underlying liver cirrhosis[7,8]. However, the most common cause of NVUGIB is peptic ulcer disease. Other causes include but are not limited to gastritis, duodenitis, angiodysplasia, non-variceal esophageal hemorrhage secondary to mucosal tears, etc. All the causes included in the study are mentioned in the Supple

The study population was derived from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) which is a part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) databases. It is one of the largest publicly available, multi-ethnic databases derived from a collection of billing data submitted by United States hospitals to state-wide data organizations. As the NIS collects data from almost all hospitals across the United States, it covers greater than 95% of the United States population. It approximates a 20% stratified sample of discharges from United States community hospitals and the dataset is further weighted to obtain national estimates. For our study period between 2016 and 2019, the NIS database was coded using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Clinical Modification/Procedure Coding System (ICD/PCS-10).

We identified all adult (≥ 18 years) hospitalizations with NVUGIB in the United States from 2016-2019. The study population was further divided into two distinct subgroups based on the presence or absence of NAFLD. Individuals ≤ 18 years of age, and those with a diagnosis of liver disease other than NAFLD were excluded from the analysis. Details on inclusion and exclusion criteria are included in the Supple

The primary outcome of interest was mortality. Secondary outcomes of interest included length of stay (LOS), hospital charges, and complications such as acute kidney injury, shock, sepsis, acute respiratory failure, acute myocardial infarction, acute liver failure, blood transfusion, need for early endoscopy, need for intubation, and need for dialysis.

The NIS does not contain patient or hospital-specific identifiers. Hence, an Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not required for this study as per the guidelines put forth by our IRB on the analysis of HCUP databases.

The statistical analysis was conducted using R software (version 4.2.1) to account for weights in the stratified survey design for the NIS database. The weights were considered during the statistical estimation process by incorporating variables for strata, clusters, and weights for discharges in the NIS database. Descriptive statistics were provided, including the mean (standard error) for continuous variables and count (percentage) for categorical variables. Mann-Whitney tests with Bonferroni corrections were used for testing differences in continuous variables, while chi-squared tests with Bonferroni corrections were used for testing the homogeneity of categorical variables. Furthermore, a multivariate regression analysis was performed to compare outcomes such as in-patient mortality, healthcare burden (mean LOS and mean total hospital charges), and complications. All analyses with P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

We identified a total of 799785 patients admitted with a primary diagnosis of NVUGIB between the years 2016 and 2019 that met our inclusion criteria. Of these 752980 (94.15%) belonged to the cohort without NAFLD and 46805 (5.85%) belonged to the cohort with NAFLD.

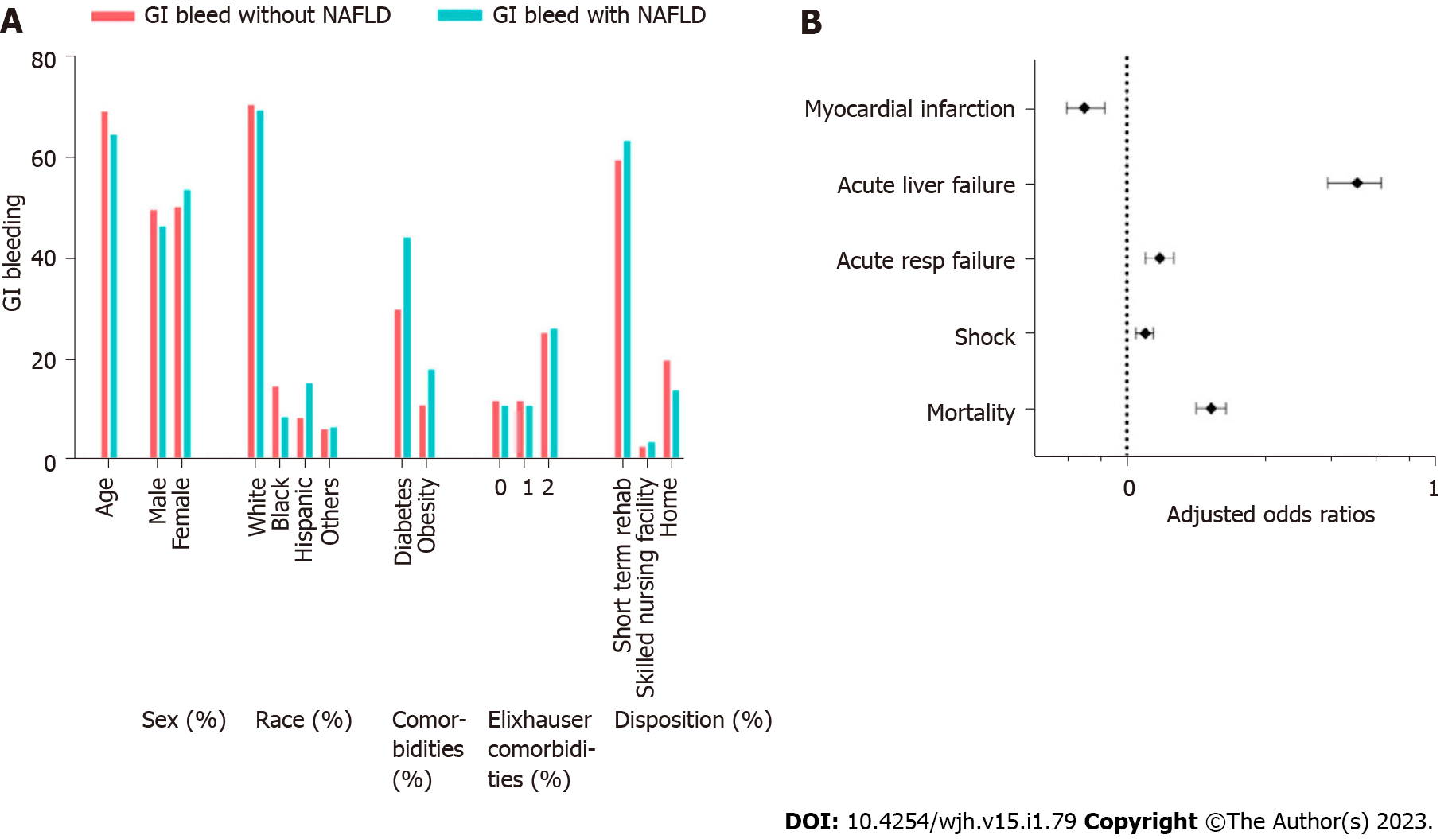

Compared to the group without NAFLD, the patients with NAFLD were significantly younger (69.3 vs 64.6, P < 0.001). In both groups, GIB was more common in females. Furthermore, there were statistically significant racial differences noted, with GIB and NAFLD being less common in blacks (8.5% vs 14.4%, P < 0.001) and more common in Hispanics (15% vs 8.2%, P < 0.001). The Elixhauser comorbidities index was almost similar in both groups, with most patients having 2 or more comorbidities. Compared to the group without NAFLD, we noted that the NAFLD group had a higher proportion of patients with diabetes (44.1% vs 30%, P < 0.001) and obesity (18% vs 11%, P < 0.001). The patient and hospital characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1.

| Variable | GI bleeding without NAFLD (n = 752980) | GI bleeding with NAFLD (n = 46805) | P value |

| Age (yr) | < 0.001 | ||

| mean ± SD | 69.3 ± 0.1 | 64.6 ± 0.2 | |

| Sex | < 0.001 | ||

| Male | 374615 (49.8%) | 21805 (46.6%) | |

| Female | 378210 (50.2%) | 24985 (53.4%) | |

| Race | < 0.001 | ||

| White | 515935 (68.5%) | 31705 (67.7%) | |

| Black | 108520 (14.4%) | 3965 (8.5%) | |

| Hispanic | 61990 (8.2%) | 7030 (15%) | |

| Other | 46220 (6.1%) | 3000 (6.4%) | |

| Insurance | < 0.001 | ||

| Medicare | 521895 (69.3%) | 28550 (61%) | |

| Medicaid | 67665 (9%) | 5460 (11.7%) | |

| Private | 122560 (16.3%) | 9670 (20.7%) | |

| Self-pay | 23575 (3.1%) | 1805 (3.9%) | |

| Other | 16250 (2.2%) | 1240 (2.6%) | |

| Hospital location | < 0.001 | ||

| Rural | 82535 (11%) | 3745 (8%) | |

| Urban nonteaching | 189130 (25.1%) | 11245 (24%) | |

| Urban teaching | 481315 (63.9%) | 31815 (68%) | |

| Hospital bedsize | < 0.001 | ||

| Small | 162810 (21.6%) | 8810 (18.8%) | |

| Medium | 236145 (31.4%) | 14245 (30.4%) | |

| Large | 354025 (47%) | 23750 (50.7%) | |

| Hospital region | |||

| Northeast | 152290 (20.2%) | 7440 (15.9%) | |

| Midwest | 163005 (21.6%) | 9370 (20%) | |

| South | 301330 (40%) | 19790 (42.3%) | |

| West | 136355 (18.1%) | 10205 (21.8%) | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 608815 (80.9%) | 39505 (84.4%) | |

| 1 | 144165 (19.1%) | 7300 (15.6%) | |

| Hypertension | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 241235 (32%) | 18195 (38.9%) | |

| 1 | 511745 (68%) | 28610 (61.1%) | |

| Diabetes | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 527140 (70%) | 26170 (55.9%) | |

| 1 | 225840 (30%) | 20635 (44.1%) | |

| Obesity | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 670225 (89%) | 38385 (82%) | |

| 1 | 82755 (11%) | 8420 (18%) | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 700625 (93%) | 44630 (95.4%) | |

| 1 | 52355 (7%) | 2175 (4.6%) | |

| Smoker | 0.598 | ||

| 0 | 658350 (87.4%) | 40765 (87.1%) | |

| 1 | 94630 (12.6%) | 6040 (12.9%) | |

| Valvular disease | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 736900 (97.9%) | 46255 (98.8%) | |

| 1 | 16080 (2.1%) | 550 (1.2%) | |

| Colorectal cancer | 0.287 | ||

| 0 | 747345 (99.3%) | 46380 (99.1%) | |

| 1 | 5635 (0.7%) | 425 (0.9%) | |

| Number of Elixhauser comorbidities | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 89900 (11.9%) | 5195 (11.1%) | |

| 1 | 191920 (25.5%) | 12280 (26.2%) | |

| 2 | 233635 (31%) | 14935 (31.9%) | |

| 3 + | 237525 (31.5%) | 14395 (30.8%) | |

| Disposition | < 0.001 | ||

| Routine | 13685 (1.8%) | 825 (1.8%) | |

| Short-term hospital | 448085 (59.5%) | 29620 (63.3%) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 21130 (2.8%) | 1775 (3.8%) | |

| Home health care | 148465 (19.7%) | 6550 (14%) | |

| Died in-hospital | 100955 (13.4%) | 6090 (13%) | |

| Other | 20205 (2.7%) | 1920 (4.1%) |

After adjusting for the variables shown in Table 1, the group with NAFLD had higher odds of inpatient mortality [4.2% vs 2.7%, adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 1.018 (1.013-1.022), P < 0.01] compared to those without NAFLD.

The difference between the total charge of hospitalizations was also statistically significant, being higher in the NAFLD group ($35092 vs $32275, P < 0.01). Patients with GIB and NAFLD were less likely to have a longer LOS (4.47 ± 4.92 vs 4.27 ± 4.53, P < 0.01). Routine discharges were the same in both groups; however, patients with NAFLD were more likely to go to a short-term rehab facility (63.3% vs 59.5%, P < 0.001).

Patients with NVUGIB and NAFLD were more likely to have worse outcomes in terms of complications including shock [13% vs 12%, aOR = 1.015 (1.008-1.023), P < 0.01], acute respiratory failure [5.2% vs 4.1%, aOR = 1.01 (1.005-1.015), P < 0.01), and acute liver failure [2% vs 0.3%, aOR = 1.016 (1.013-1.019), P < 0.01]. Peculiarly, patients with NAFLD were less likely to suffer from an acute myocardial infarction (MI). However, they were 1.04 times more likely to undergo an endoscopy. The clinical outcomes, healthcare utilization, and complications are summarized in Table 2.

| Outcomes | GI bleeding with NAFLD (n = 45215) | GI bleeding without NAFLD (n = 726490) | Univariate P value | OR or regression coefficient (95%CI) | Multivariate P value |

| Mortality | 1920 (4.2%) | 20205 (2.7%) | < 0.01 | 1.018 (1.013-1.022) | < 0.01 |

| Length of stay | 4.47 ± 5.03 | 4.26 ± 4.51 | < 0.01 | 0.27 (0.17-0.38) | < 0.01 |

| Total charges | 35092 ± 21749 | 32275 ± 21011 | < 0.01 | 2148 (1677-2618) | < 0.01 |

| Acute kidney injury | 10150 (22.4%) | 159955 (21.2%) | 1 | 1.012 (1.003-1.021) | 1 |

| Shock | 6015 (13.3%) | 87425 (11.6%) | < 0.01 | 1.015 (1.008-1.023) | < 0.01 |

| Sepsis | 1000 (2.2%) | 12640 (1.7%) | 0.14 | 1.005 (1.002-1.008) | 1 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 2330 (5.2%) | 30540 (4.1%) | < 0.01 | 1.01 (1.005-1.015) | < 0.01 |

| Acute MI | 955 (2.1%) | 22635 (3%) | < 0.01 | 0.992 (0.989-0.995) | < 0.01 |

| Acute liver failure | 915 (2%) | 2560 (0.3%) | < 0.01 | 1.016 (1.013-1.019) | < 0.01 |

| Blood transfusion | 12505 (27.7%) | 210580 (28%) | 0.14 | 1.003 (0.993-1.012) | 1 |

| Endoscopy | 12500 (27.6%) | 169385 (22.5%) | < 0.01 | 1.038 (1.028-1.048) | < 0.01 |

| Intubation | 140 (0.3%) | 1255 (0.2%) | 0.28 | 1.001 (1-1.003) | 1 |

| Dialysis | 750 (1.7%) | 11525 (1.5%) | 1 | 1.001 (0.998-1.003) | 1 |

Many studies have been conducted to evaluate variceal bleeding in liver disease and cirrhosis. There is a paucity of published data evaluating NVUGIB in patients with NAFLD without cirrhosis[9]. Given the increasing incidence of NAFLD, understanding the patient demographics, clinical outcomes and associations is of practical importance to gastroenterologists and hepatologists[10-13].

In our analysis, it was noted that patients with both GIB and NAFLD were younger, with a higher incidence in the Hispanic population, and were seen more in population groups with diabetes and obesity. Al

Our study found increased odds of patients with NAFLD presenting with GIB at a younger age. This is in contrast to available literature[14]. This is probably related to patients having an increased risk of developing NAFLD at a younger age with the increasing risk factors especially the increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome in young adults, which is one of the major risk factors for NAFLD[15]. Patients with NAFLD are more prone to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) including coronary artery disease (CAD)[16-18]. With the increased CAD prevalence and percutaneous interventions for CAD, an increasing number of patients are on antiplatelet medications such as aspirin and clopidogrel which likely predispose them to GIB. Despite ASCVD still being the highest cause of mortality in NAFLD patients, in our study, we found that the odds of NAFLD patients with GIB developing an acute MI were actually less[19]. There are studies with conflicting data regarding acute cardiac events in patients admitted for other NAFLD-related complications[14,20].

Studies have also demonstrated a positive association between H. pylori infection and predisposition to NAFLD incidence[21,22]. This underlying relationship can also explain the increased risk of developing gastric ulcers and subsequent bleeding[23]. Studies have shown that aspirin can decrease the progression of fibrosis in NAFLD. Although it is not known if this has led to increased use of aspirin in this population but could also be a contributing factor.

Previous studies have shown that NAFLD has an increased prevalence in the Hispanic population[24-26]. This also resonates with our results, as NAFLD with GIB was higher in Hispanics. Non-variceal GIB from ulcer disease is seen more in the African-American population[27,28]. However, in our study we found that patients with NAFLD were less likely to have NVUGIB, indicating a possible protective effect. The mechanism for the same is unclear. This association needs to be further studied.

Patients with NAFLD and GIB were found to have a longer LOS and showed increased odds of having higher hospital charges and discharges to short-term rehab facilities, thus leading to increased utilization of healthcare resources and an increased economic burden. This trend has been seen in multiple studies and was associated with the established risk factors of NAFLD and metabolic syndrome, especially diabetes[29,30]. Another reason for the economic burden could be the higher incidence of complications among these patients[31,32].

Murine models have shown that hepatic steatosis and NAFLD lead to aberrant corticosterone release which could put patients at increased risk of developing and delayed recovery from shock[33]. It was shown that reduced lung function is an independent risk factor for the development of NAFLD which can theoretically increase the risk of developing acute respiratory failure[34]. It was also shown that NAFLD and metabolic syndrome can be associated with impaired lung function predominantly due to abdominal obesity[35]. Along with the increased risk of shock and respiratory failure, the NAFLD population is inherently at risk for the development of acute on chronic liver failure from chronic hepatocyte inflammation and increased mortality in the presence of multiple comorbidities[36].

Using the NIS database gives nationwide generalizability, a large patient population, and multiple clinical parameters. It provides an excellent representative sample with results in a reliable and valid range[37]. Our study should be prudently interpreted as the NIS database has its own limitations. It does not include how NAFLD was diagnosed and the specific diagnostic modality that was used. This contributes to variations in the prevalence of NAFLD amongst various geographical regions and income groups.

Another drawback was that given it is a nationwide sample and with the use of ICD-10 CM coding, there may have been imprecision and erroneous coding causing an over or underestimation of the cases. ICD nomenclature does not include the spectrum of liver disease to further stratify based on severity in the NAFLD population. Although Elixhauser comorbidity indices were used to account for the various systemic comorbidities, the calculation of liver-specific indices such as model for end-stage liver disease score was not possible given the non-availability of laboratory data.

With the increasing worldwide incidence of liver disease from NAFLD and with the rising frequency of hospitalizations[37,38], emphasis should be placed on aggressive risk factor modification and secondary prevention of the disease and its numerous complications. Further longitudinal studies are needed to study NVUGIB in the NAFLD population and develop tools to help guide clinicians in the early detection of patients at risk for NVUGIB. This will help reduce multiple hospitalizations, increasing financial burden with prolonged hospital stays and mortality.

Our analysis showed that patients with NVUGIB have higher mortality, increased complications, longer LOS and higher hospital charges demonstrating the increased morbidity and economic burden of NAFLD.

With the increasing prevalence, morbidity and mortality of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and worse outcomes with concomitant conditions, we wanted to determine the effect of NAFLD on a commonly seen in-patient presentation, non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB).

There are studies showing the effect of alcoholic liver disease on both variceal and NVUGIB, along with studies showing an increased risk of variceal bleeding and screening in patients with NAFLD. However, there have been no studies showing the influence of NAFLD on NVUGIB. Our aim was to try to bridge this gap.

Our objective was to examine whether the presence of NAFLD led to worse outcomes in patients with NVUGIB.

We used the National Inpatient Sample database to ensure generalizability of findings. We compared the two cohorts of NAFLD with and without NVUGIB on the basis of mortality which was the primary outcome and secondary outcomes such as the length of stay, hospital charges, and complications.

It was shown that patients with NVUGIB and NAFLD had higher odds of mortality, higher hospital charges and more complications such as shock, acute respiratory failure and acute liver failure.

Co-existence of NAFLD and NVUGIB was associated with higher mortality, morbidity and economic burden.

Because of increased morbidity and mortality due to NAFLD, aggressive risk management should be a focus. Also, further studies should be performed to stratify patients with NAFLD that are at higher risk of NVUGIB so that they can be identified by clinicians and the mortality, morbidity and economic burden can be reduced.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Crocé LS, Italy; Giacomelli L, Italy S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Younossi Z, Tacke F, Arrese M, Chander Sharma B, Mostafa I, Bugianesi E, Wai-Sun Wong V, Yilmaz Y, George J, Fan J, Vos MB. Global Perspectives on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2019;69:2672-2682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1415] [Cited by in RCA: 1317] [Article Influence: 219.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ratziu V, Bellentani S, Cortez-Pinto H, Day C, Marchesini G. A position statement on NAFLD/NASH based on the EASL 2009 special conference. J Hepatol. 2010;53:372-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 723] [Cited by in RCA: 789] [Article Influence: 52.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | McGraw-Hill Education. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 20th edition. Shanahan JF, Davis KJ, editors. Palatino: Cenveo® Publisher Services, 2018. |

| 4. | Simon TG, Roelstraete B, Khalili H, Hagström H, Ludvigsson JF. Mortality in biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: results from a nationwide cohort. Gut. 2021;70:1375-1382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 423] [Cited by in RCA: 430] [Article Influence: 107.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liu Y, Zhong GC, Tan HY, Hao FB, Hu JJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:11124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, Adams LA, Bjornsson ES, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Mills PR, Keach JC, Lafferty HD, Stahler A, Haflidadottir S, Bendtsen F. Liver Fibrosis, but No Other Histologic Features, Is Associated With Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:389-97.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2304] [Cited by in RCA: 2229] [Article Influence: 222.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Biecker E. Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Cirrhotic Patients with Portal Hypertension. ISRN Hepatol. 2013;2013:541836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zullo A, Soncini M, Bucci C, Marmo R; Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio dell'Emorragia Digestiva (GISED) (Appendix). Clinical outcomes in cirrhotics with variceal or nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding: A prospective, multicenter cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:3219-3223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | González-González JA, García-Compean D, Vázquez-Elizondo G, Garza-Galindo A, Jáquez-Quintana JO, Maldonado-Garza H. Nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis. Clinical features, outcomes and predictors of in-hospital mortality. A prospective study. Ann Hepatol. 2011;10:287-295. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Sanyal AJ, Van Natta ML, Clark J, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Diehl A, Dasarathy S, Loomba R, Chalasani N, Kowdley K, Hameed B, Wilson LA, Yates KP, Belt P, Lazo M, Kleiner DE, Behling C, Tonascia J; NASH Clinical Research Network (CRN). Prospective Study of Outcomes in Adults with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1559-1569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 703] [Article Influence: 175.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Krige JE, Kotze UK, Distiller G, Shaw JM, Bornman PC. Predictive factors for rebleeding and death in alcoholic cirrhotic patients with acute variceal bleeding: a multivariate analysis. World J Surg. 2009;33:2127-2135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J, Groszmann RJ. Portal hypertension and variceal bleeding--unresolved issues. Summary of an American Association for the study of liver diseases and European Association for the study of the liver single-topic conference. Hepatology. 2008;47:1764-1772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Burroughs AK, Triantos CK, O'Beirne J, Patch D. Predictors of early rebleeding and mortality after acute variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:72-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vora P, Pietila A, Peltonen M, Brobert G, Salomaa V. Thirty-Year Incidence and Mortality Trends in Upper and Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Finland. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2020172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hirode G, Wong RJ. Trends in the Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in the United States, 2011-2016. JAMA. 2020;323:2526-2528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 624] [Article Influence: 124.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Brouwers MCGJ, Simons N, Stehouwer CDA, Isaacs A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease: assessing the evidence for causality. Diabetologia. 2020;63:253-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kasper P, Martin A, Lang S, Kütting F, Goeser T, Demir M, Steffen HM. NAFLD and cardiovascular diseases: a clinical review. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021;110:921-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 76.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Targher G, Byrne CD, Tilg H. NAFLD and increased risk of cardiovascular disease: clinical associations, pathophysiological mechanisms and pharmacological implications. Gut. 2020;69:1691-1705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 510] [Article Influence: 102.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Haflidadottir S, Jonasson JG, Norland H, Einarsdottir SO, Kleiner DE, Lund SH, Björnsson ES. Long-term follow-up and liver-related death rate in patients with non-alcoholic and alcoholic related fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Alexander M, Loomis AK, van der Lei J, Duarte-Salles T, Prieto-Alhambra D, Ansell D, Pasqua A, Lapi F, Rijnbeek P, Mosseveld M, Avillach P, Egger P, Dhalwani NN, Kendrick S, Celis-Morales C, Waterworth DM, Alazawi W, Sattar N. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident acute myocardial infarction and stroke: findings from matched cohort study of 18 million European adults. BMJ. 2019;367:l5367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Okushin K, Tsutsumi T, Ikeuchi K, Kado A, Enooku K, Fujinaga H, Moriya K, Yotsuyanagi H, Koike K. Helicobacter pylori infection and liver diseases: Epidemiology and insights into pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3617-3625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Castaño-Rodríguez N, Mitchell HM, Kaakoush NO. NAFLD, Helicobacter species and the intestinal microbiome. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31:657-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Jiang ZG, Feldbrügge L, Tapper EB, Popov Y, Ghaziani T, Afdhal N, Robson SC, Mukamal KJ. Aspirin use is associated with lower indices of liver fibrosis among adults in the United States. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:734-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Grundy SM, Hobbs HH. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004;40:1387-1395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2633] [Cited by in RCA: 2695] [Article Influence: 128.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 25. | Bambha K, Belt P, Abraham M, Wilson LA, Pabst M, Ferrell L, Unalp-Arida A, Bass N; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network Research Group. Ethnicity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2012;55:769-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mazi TA, Borkowski K, Newman JW, Fiehn O, Bowlus CL, Sarkar S, Matsukuma K, Ali MR, Kieffer DA, Wan YY, Stanhope KL, Havel PJ, Medici V. Ethnicity-specific alterations of plasma and hepatic lipidomic profiles are related to high NAFLD rate and severity in Hispanic Americans, a pilot study. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;172:490-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wollenman CS, Chason R, Reisch JS, Rockey DC. Impact of ethnicity in upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:343-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sood N, Jurkowski Z, Daitch ZE, Friedenberg F, Heller SJ. S623 changes in demographics and prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in gastric and duodenal ulcers at an urban tertiary care university hospital. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:S283-S283. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Nguyen AL, Park H, Nguyen P, Sheen E, Kim YA, Nguyen MH. Rising Inpatient Encounters and Economic Burden for Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:698-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Younossi ZM, Blissett D, Blissett R, Henry L, Stepanova M, Younossi Y, Racila A, Hunt S, Beckerman R. The economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States and Europe. Hepatology. 2016;64:1577-1586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 694] [Cited by in RCA: 914] [Article Influence: 101.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lv WS, Sun RX, Gao YY, Wen JP, Pan RF, Li L, Wang J, Xian YX, Cao CX, Zheng M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3134-3142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sayiner M, Otgonsuren M, Cable R, Younossi I, Afendy M, Golabi P, Henry L, Younossi ZM. Variables Associated With Inpatient and Outpatient Resource Utilization Among Medicare Beneficiaries With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease With or Without Cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:254-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Huang HC, Tsai MH, Lee FY, Lin TY, Chang CC, Chuang CL, Hsu SJ, Hou MC, Huang YH. NAFLD Aggravates Septic Shock Due to Inadequate Adrenal Response and 11β-HSDs Dysregulation in Rats. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Song JU, Jang Y, Lim SY, Ryu S, Song WJ, Byrne CD, Sung KC. Decreased lung function is associated with risk of developing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A longitudinal cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0208736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Leone N, Courbon D, Thomas F, Bean K, Jégo B, Leynaert B, Guize L, Zureik M. Lung function impairment and metabolic syndrome: the critical role of abdominal obesity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:509-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sundaram V, Jalan R, Shah P, Singal AK, Patel AA, Wu T, Noureddin M, Mahmud N, Wong RJ. Acute on Chronic Liver Failure From Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Growing and Aging Cohort With Rising Mortality. Hepatology. 2021;73:1932-1944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Adejumo AC, Samuel GO, Adegbala OM, Adejumo KL, Ojelabi O, Akanbi O, Ogundipe OA, Pani L. Prevalence, trends, outcomes, and disparities in hospitalizations for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States. Ann Gastroenterol. 2019;32:504-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Singh Y, Gogtay M, Gurung S, Trivedi N, Abraham GM. Assessment of Predictive Factors of Hepatic Steatosis Diagnosed by Vibration Controlled Transient Elastography (VCTE) in Chronic Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Patients. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2022;12. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |