Published online Feb 15, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i2.381

Revised: August 14, 2002

Accepted: August 27, 2002

Published online: February 15, 2003

AIM: To investigate the possibility of urethral reconstruction with a free colonic mucosa graft and to present our preliminary experience with urethral substitution using a free graft of colonic mucosa for treatment of 7 patients with complex urethral stricture of a long segment.

METHODS: Ten female dogs underwent a procedure in which the urethral mucosa was totally removed and replaced with a free graft of colonic mucosa. A urodynamic study was performed before the operation and sacrifice. The dogs were sacrificed 8 to 16 wk after the operation for histological examination of urethra. Besides, 7 patients with complex urethral stricture of a long segment were treated by urethroplasty with the use of a colonic mucosal graft. The cases had undergone an average of 3 previous unsuccessful repairs. Urethral reconstruction with a free graft of colonic mucosa ranged from 10 to 17 cm (mean 13.1 cm). Follow-up included urethrography, urethroscopy and uroflowmetry.

RESULTS: Urethral stricture developed in 1 dog. The results of urodynamic studies showed that the difference in the maximum urethral pressure between the pre-operation and pre-sacrifice in the remaining 9 dogs was not of significance (P > 0.05). Histological examination revealed that the colonic free mucosa survived inside the urethral lumen of the 10 experimental dogs. Plicae surface and unilaminar cylindric epithelium of the colonic mucosa was observed in dogs sacrificed 8 wk after the operation. The plicae surface and unilaminar cylindric epithelium of the colonic mucosa was not observed, and metaplastic transitional epithelium covered a large proportion of the urethral mucosa in dogs sacrificed 12 wk after the operation. Clinically, the patients were followed up for 3-18 mo postoperatively (mean 8.5 mo). Meatal stenosis was developed in 1 patient 3 mo postoperatively and needed reoperation. The patient was voiding very well with urinary peak flow 28.7 mL/s during the follow-up of 9 mo after reoperation. The other patients were voiding well with urinary peak flow greater than 15 mL/s. Urethrogram revealed a patent urethra with an adequate lumen with no significant graft sacculation. Neither necrosis of neourethral mucosa nor stenosis at the anastomosis sites has been observed on urethroscopy in 4 patients over 6 mo after operation.

CONCLUSION: Urethral mucosa can be replaced by colonic mucosa without damaging the continence mechanism in female dogs. Colonic mucosa graft urethral substitution is a feasible procedure for the treatment of complex urethral stricture of a long segment. The technique may be considered when more conventional options have failed or are contraindicated.

- Citation: Xu YM, Qiao Y, Sa YL, Zhang J, Zhang HZ, Zhang XR, Wu DL, Chen R. One-stage urethral reconstruction using colonic mucosa graft: An experimental and clinical study. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9(2): 381-384

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v9/i2/381.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i2.381

In most instances, primary reconstruction for urethral strictures can be accomplished with local penile or preputial skin and buccal or bladder mucosa[1-11]. However, in patients with complex, long-segment urethral strictures and significant scar tissue formation after the failure of previous anterior urethroplasty still present an operative challenge. The key is to obtain a suitable substitute for urethral reconstruction.

From the viewpoint of postoperative quality of life, neobladder construction is superior to urinary diversion in patients who have to undergo cystectomy for bladder cancer. However, in patients having cystectomy as definitive treatment for bladder cancer, the overall risk of urethral recurrence of transitional cell carcinoma is between 0.7% and 18%[16]. The urethral recurrence of bladder cancer would be reduced, if the urethral mucosa can be replaced by another mucosa without damaging urethral sphincter function. We explored the feasibility of urethral reconstruction with a free graft of colonic mucosa for the treatment of complicated long segment strictures or reducing urethral recurrence of bladder cancer in patients who have to undergo cystectomy for bladder cancer and neobladder construction. We investigated colonic mucosa as a novel substitute for urethral reconstruction in 10 dogs before performing the operation in 7 patients with severe lengthy urethral stricture.

Ten adult mongrel female dogs, weighing 14.5 kg to 28 kg, were used for the experiment. Under intravenous pentobarbital anesthesia, the dogs were first used for urodynamic studies and then underwent a procedure in which urethral mucosa was replaced with a free graft of colonic mucosa. With a partial resection of the pubic symphysis, the urethra was incised longitudinally at its full length on the ventral side and the urethral mucosa was totally removed. The sigmoid colon was exposed and 8-10 cm. in length colectomy was performed. The digestive connection was immediately restored by an end-to-end anastomosis. A mucosa graft was harvested from the resected colon. After tailoring the mucosa graft, excess submucosal tissue, fat or muscle was carefully dissected away to optimize subsequent vascularization. The free graft was tubularized over a 14 Fr catheter with one layer of 5-zero polyglactin running sutures. The proximal end of the graft was sutured to the edge of the bladder neck mucosa and the distal end to the external meatus with interrupted 5-zero polyglactin suture. The urethral muscle layer was then closed with one layer of 4-zero polyglactin interrupted sutures. The urethral catheter was left indwelling to provide bladder drainage for 7 to 10 d after the operation. Ampicilling (2 gm. per day) was given intravenously for 5 d after the operation.

Postoperatively, the urinary stream and external meatus were observed periodically. To determine the influence of the longitudinal urethral incision on urethral continence mechanism, Urodynamic study was carried out again 8 to 16 wk (8 wk 2, 12 wk 6 and 16 wk 2) after the operation. The data from the urodynamic study were statistically analyzed by t test. After the urodynamic study, the dogs were sacrificed for histological examination of the urethra.

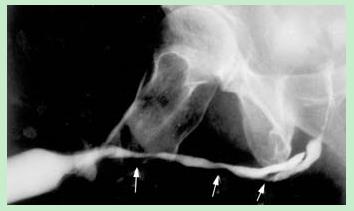

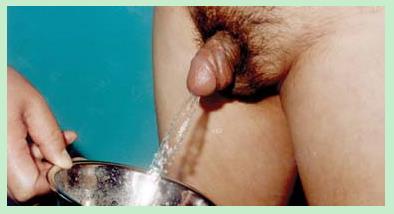

Between September 2000 and April 2002, 7 men aged 18 to 58 years (median 39.5) with complex lengthy urethral stricture underwent urethral reconstruction with a free colonic mucosa graft. The etiology of the urethral stricture was trauma and urethritis in 5 patients, perineal hypospadias in 2. All patients had a history of extensive urethral stricture disease for 1.5 to 9 years (median age 3.5 years) and had undergone an average of 3 previous unsuccessful repairs (1-5 times) or repeated urethral dilation. The urethral stricture was 10 to 17 cm long (median 13.1 cm). 5 patients underwent a procedure of suprapubic cystostomy because of severe urethral stricture or atresia. 2 patient presented with strangury cause by severe urethral stricture. Uroflowmetry examination showed the urinary peak flow was 1 mL/s. Retrograde urethrogram demonstrated multiple urethral strictures and pseudopath (Figure 1).

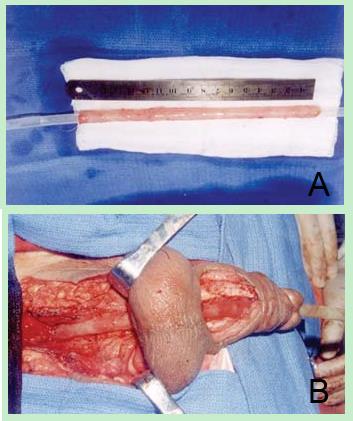

Urethral reconstruction was performed with the patients under general anesthesia. Strictured or atretic urethra and scar tissue were excised and the penis was straightened. The urethra defected 10 to 17 cm in length. 10 to 15 cm long sigmoid colon with its blood pedicle was isolated from the intestinal tract. The digestive connection was immediately restored by an end-to-end anastomosis. A full thickness mucosal graft was harvested from the isolated colon and the isolated colon was resected afterward. After tailoring the mucosa graft, excess submucosal tissue, fat or muscle was carefully dissected away to optimize subsequent vascularization. An unstretched colonic mucosa, 10 to 17 cm in length and 2.5-3 cm in width, was tubularized over an 18 to 22 F fenestrated silicone stent with interrupted 5-zero polyglactin suture to create a neourethra (Figure 2A). An end-to-end anastomosis was performed between normal urethra and neourethra with interrupted 5-zero polyglactin suture in 4 patients (Figure 2B). In the remaining 3 patients one end of neourethra was anastomosed with proximal normal urethra and the other end of the neourethra was through the glanular tunnel to form new meatus. The penis was wrapped with soft, elastic, and roller bandage incorporating the traction suture into the dressing. Strips of elastic adhesive were placed over this to keep the penis in the erect position.

The bladder drainage was through the suprapubic catheter and the urethral silicone stent was left indwelling for 14 d. The patients underwent urethrography, urethroscopy and uroflowmetry 3 mo after operation.

Nine dogs were able to void normally after removal of the catheter and the external meatus were dry whenever examined before urination. Urodynamic studies showed that the maximum urethral pressure ranged from 34-70 cm H2O (56.5 ± 11.05, mean ± S.D.) before the operation and ranged from 43-82 cm H2O (51.75 ± 13.36, mean ± S.D.) before sacrifice. There was no significant difference in the maximum urethral pressure between pre-operation and pre-sacrifice (t = 1.22, P = 0.26). These findings indicated that the dogs were continent in the usual state. The one remaining dog was not voiding well and had a thin urinary stream. A urodynamic study was not done in this dog postoperatively.

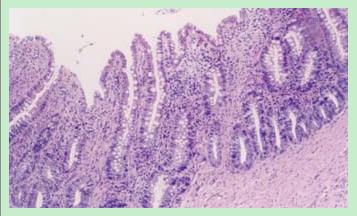

At sacrifice, the colonic mucosa-replaced urethra was macroscopically normal in 9 dogs. No necrosis or erosion was observed on the urethra epithelium in these dogs (Figure 3). In the other 1 dog, a slightly distended bladder was observed; 3 stones, soybean in size, were found in the bladder and a urethral stricture of 1 cm in length developed at the bladder neck.

Histological examination of the urethras showed that the colonic mucosa graft survived inside the urethral lumen. Plicae surface and unilaminar cylindric epithelium of the colonic mucosa was observed in dogs sacrificed 8 wk after the operation (Figure 4).

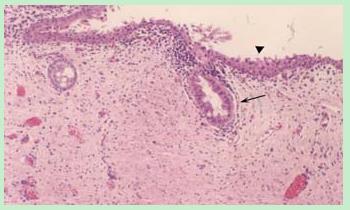

The plicae surface and unilaminar cylindric epithelium of colonic mucosa was not observed in dogs sacrificed at 12 wk postoperatively. Metaplastic transitional epithelium covered a large proportion of the urethral mucosa and some degree of atrophy of the colonic crypts were seen in dogs sacrificed at 12 wk after the operation (Figure 5). In the dog with the urethral stricture, the submucosal layer was thickened with inflammatory cell infiltration at the site of the stricture.

The patients were followed up for 3-18 mo postoperatively (mean 8.5 mo). Meatal stenosis was developed in 1 patient 3 mo postoperatively and needed reoperation. 9 mo later the patient returned to the hospital and the new urethra was found to be most satisfactory. Uroflowmetry examination showed the urinary peak flow was 28.7 mL/s. Hyperplasia of the verumontanum was observed during urethroscopy and transurethral colliculectomy carried out in 1 patient over 14 mo after operation. Uroflowmetry examination showed the urinary peak flow was 46.5 mL/s postoperatively. The other patients were voiding well with urinary peak flow greater than 15 mL/s (from 16 to 27.8 mL/s) (Figure 6A). Urethrogram revaled a patent urethra with an adequate lumen with no significant graft sacculation (Figure 6B). Neither necrosis of neourethral mucosa nor stenosis at the anastomosis sites has been observed on urethroscopy in 4 patients over 6 mo after operation.

Up to now, a variety of tissues have been used for urethral reconstruction, including full thickness skin graft, free bladder or buccal mucosa and pedicled flaps[5-10,13-15]. In 1996, Iiziuka et al[17] reported on the total replacement of urethra mucosa with oral mucosa in a dog model, with the intention of reducing the recurrence rate of urethral cancer in bladder cancer patients requiring radical cystoprostatectomy. However, substituting buccal mucosa in total urethral reconstruction is difficult in humans, and it may not be useful for the treatment of complicated long segment urethral strictures because of limited material. The use of bladder mucosa may also be difficult in cases with a previous bladder operation, chronic cystitis or even long-term suprapubic cystostomy.

Recently, Bales et al[12]. reported a novel technique to urethral reconstruction using tailored jejunal free tissue transfer to reconstruct the anterior urethra in 2 patients with complex urethral stricture. The patients have good urinary streams and are able to void in the standing position. However, the technique is time-consuming and surgeon must have experienced with microvascular anastomosis.

The appendix mucosa as a graft in urethroplasty was used by Lexer in 1911 for the treatment of hypospadias[18]. The result was difficult to interpret as no complete histological examination or follow-up had originally been attempted. In fact, the appendix may not be available consequent to a previous appendectomy; it also may not be useful for the treatment of complicated long length urethral strictures because of inappropriate size and fibrous obstruction[19]. Lebret et al[18] studied the histology of the colonic mucosa as a graft for urethral construction in Spague-Dawley rats. They found that the glandular epithelium of colonic mucosa had been transformed into a typical urothelium 6 wk to 3 mo after operation. In our study, although plicate surface and unilaminar cylindric epithelium of colonic mucosa was observed in dogs sacrificed 8 wk after the operation (Figure 4), the plicate surface mucosa and unilaminar cylindric epithelium were not observed in dogs sacrificed 12 wk postoperatively.

Metaplastic transitional epithelium covered a large proportion of the urethral mucosa and some degree of atrophy of the colonic crypts were seen in those dogs (Figure 5). This is similar to results published by Lebret et al[18].

In these experiments, urethral stricture developed at the anastomotic site between the colonic mucosa and bladder neck mucosa in one dog. This may be related to a catheter dropping early; urine leakage from the anastomotic site probably caused an inflammatory reaction leading to stricture. Whether a longitudinal incision of the urethra will damage sphincteric function is worthy of consideration. To measure urine leakage, a 10-minute pad test was performed once a month in the investigation of Iiziuka et al[17]. There was no significant difference in the weight increase of the pad among the control, sham-operated and mucosa-replaced dogs. In our study, 9 dogs were able to void normally after removal the catheter and the external meatus was dry whenever examined before urination. Data from urodynamic study showed no significant difference in maximum urethral pressure pre-operation and pre-sacrifice (P > 0.05), indicate that a longitudinal incision of the urethra does not damage sphincter function in female dogs.

Colonic mucosa graft urethral reconstruction is a one-stage urethraplasty for the treatment of complex urethral lengthy stricture. The key to a successful transplantation of the colonic mucosa, as with any free graft, depends on whether the neovascularization is established. The following conditions are necessary for the success: (1) scar tissue was excised as long as possible and the bed to receive the graft must be well vascularized, (2) an ischemia time of the colonic mucosa should be short as far as possible, (3) to avoid wound infection and sterile urine should be ensured. The clinical results of our patients are satisfactory. They have a functioning urethra of good caliber throughout the entire length (Figure 6A, Figure 6B). Uroflowmetry examination showed the maximum flow rate was greater than 15 mL/s. Being more invasive than the use of other types of grafts, the technique may have limited applications in the practice of urethroplasty. However, we believe that colonic mucosa graft should be used in patients with complex lengthy urethral stricture after the failure of previous anterior urethroplasty and penial skin and/or bladder mucosa are not available. The technique has opened up a new way for the treatment of complex lengthy urethral stricture.

Our study indicates that urethral mucosa can be replaced with colonic mucosa and this technique can provide rich material for urethroplasty. The colonic mucosa is easy to harvest; the colonic mucosal graft is elastic and shows only a slight tendency to retract. The technique is particularly useful for the treatment of complicated long segment strictures (> 10 cm in length) or reducing urethral recurrence of bladder cancer in patients who undergo cystectomy for bladder cancer and neobladder construction.

Edited by Zhang JZ

| 1. | Andrich DE, Mundy AR. Urethral strictures and their surgical treatment. BJU Int. 2000;86:571-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kessler TM, Fisch M, Heitz M, Olianas R, Schreiter F. Patient satisfaction with the outcome of surgery for urethral stricture. J Urol. 2002;167:2507-2511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Santucci RA, Mario LA, McAninch JW. Anastomotic urethroplasty for bulbar urethral stricture: Analysis of 168 patients. J Urol. 2002;167:1715-1719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Joseph JV, Andrich DE, Leach CJ, Mundy AR. Urethroplasty for refractory anterior urethral stricture. J Urol. 2002;167:127-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Palminteri E, Lazzeri M, Guazzoni G, Turini D, Barbagli G. New 2-stage buccal mucosal graft urethroplasty. J Urol. 2002;167:130-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kane CJ, Tarman GJ, Summerton DJ, Buchmann CE, Ward JF, O'Reilly KJ, Ruiz H, Thrasher JB, Zorn B, Smith C. Multi-institutional experience with buccal mucosa onlay urethroplasty for bulbar urethral reconstruction. J Urol. 2002;167:1314-1317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Meneghini A, Cacciola A, Cavarretta L, Abatangelo G, Ferrarrese P, Tasca A. Bulbar urethral stricture repair with buccal mucosa graft urethroplasty. Eur Urol. 2001;39:264-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Greenwell TJ, Venn SN, Mundy AR. Changing practice in anterior urethroplasty. BJU Int. 1999;83:631-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Hemal AK, Dorairajan LN, Gupta NP. Posttraumatic complete and partial loss of urethra with pelvic fracture in girls: An appraisal of management. J Urol. 2000;163:282-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McAninch JW, Morey AF. Penile circular fasciocutaneous skin flap in 1-stage reconstruction of complex anterior urethral strictures. J Urol. 1998;159:1209-1213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Al-Ali M, Al-Hajaj R. Johanson's staged urethroplasty revisited in the salvage treatment of 68 complex urethral stricture patients: presentation of total urethroplasty. Eur Urol. 2001;39:268-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bales GT, Kuznetsov DD, Kim HL, Gottlieb LJ. Urethral substitution using an intestinal free flap: A novel approach. J Urol. 2002;168:182-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pansadoro V, Emiliozzi P, Gaffi M, Scarpone P. Buccal mucosa urethroplasty for the treatment of bulbar urethral strictures. J Urol. 1999;161:1501-1503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | El-Sherbiny MT, Abol-Enein H, Dawaba MS, Ghoneim MA. Treatment of urethral defects: skin, buccal or bladder mucosa, tube or patch An experimental study in dogs. J Urol. 2002;167:2225-2228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wadhwa SN, Chahal R, Hemal AK, Gupta NP, Dogra PN, Seth A. Management of obliterative posttraumatic posterior urethral strictures after failed initial urethroplasty. J Urol. 1998;159:1898-1902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Freeman JA, Esrig D, Stein JP, Skinner DG. Management of the patient with bladder cancer. Urethral recurrence. Urol Clin North Am. 1994;21:645-651. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Iizuka K, Muraishi O, Maejima T, Kitami Y, Xu YM, Watanabe K, Ogawa A. Total replacement of urethral mucosa with oral mucosa in dogs. J Urol. 1996;156:498-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |