Published online Feb 15, 2000. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i1.45

Revised: November 2, 1999

Accepted: November 15, 1999

Published online: February 15, 2000

AIM: To investigate the incidence and management of nutritional deficiencies following a gastrectomy.

METHODS: A gastrectomy population of 227 patients in London was followed up for 30 years after operation to detect and treat nutritional deficiencies.

RESULTS: By the end of the first decade iron deficiency was the commonest problem. Vitamin B12 deficiency became more important in the second decade. During the third decade both reached equal prevalence, being found in some 90% of the female and 70% of the male residual population. Vitamin D deficiency was a lesser problem, reaching its climax in the second decade. Overall, all women fared worse than men.

CONCLUSION: The importance of long-term follow-up of gastrect omy patients foriron, Vitamin B12 and Vitamin D deficiencies is emphasised.

- Citation: Tovey FI, Hobsley M. Post-gastrectomy patients need to be followed up for 20-30 years. World J Gastroenterol 2000; 6(1): 45-48

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v6/i1/45.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v6.i1.45

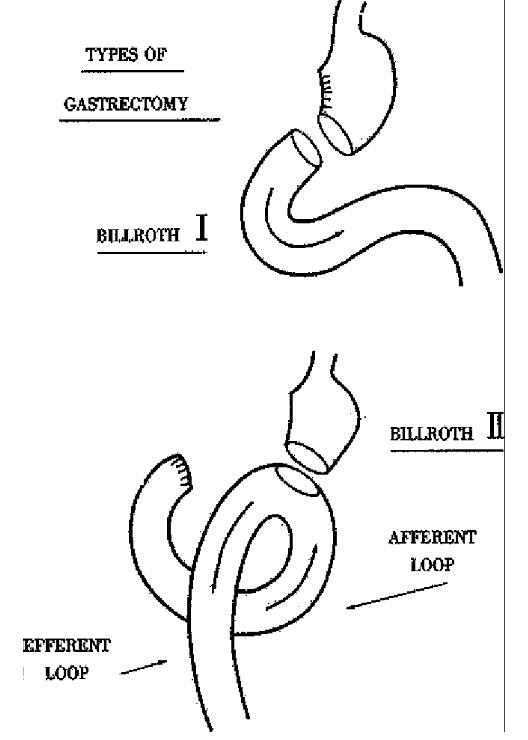

In 1981 and 1984, through the courtesy of The Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, the first author visited centres in the north and south of China to gather information about the prevalence of duodenal ulcer and its relationship to the staple diets. It was noted that the standard operation for duodenal ulcer in many centres was either a Billroth II (gastrojejunal) or a Billroth I (gastroduodenal anast omosis) gastrectomy (Figure 1). This raises the possibility that at the present time there might be a gastrectomy population in China of 25-30 years standing, w ho may have developed nutritional disorders as a result of their operation. Our experience with the study of patients 25-30 years after gastrectomy and on a Wes tern diet may serve as a guide to the frequency of these problems.

We report the outcome of a longitudinal study in the UK. The study was performed at University College Hospital in London on patients who underwent a gastrectomy between 1955 and 1960[1]. In 1969 contact was made with 227 patients, and although the number diminished from movement elsewhere or deaths, the remainder were followed up regularly until 1990. The population included 186 patients who had undergone a Billroth II gastrectomy (male 141, female 45) and 41 who had undergone a Billroth I gastrectomy (male 24, female 17). After an interval of 10-15 years following the operation they were screened annually, or more often when indicated, and the following investigations were made to detect possible nutritional disorders[1].

Clinical investigation (on first attendance) The patients were weighed. Compared with the patient’s ideal pre-operative weight, a loss of up to 4.5 kg was regarded as moderate loss and a greater loss as severe.

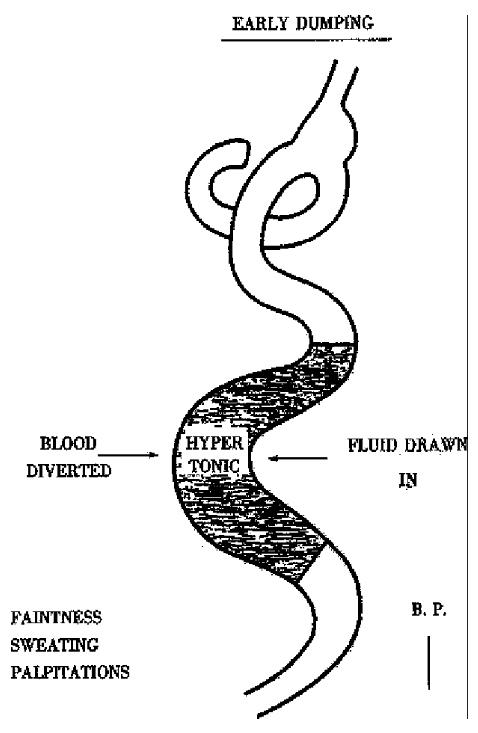

A record was made of any post-prandial symptoms including reduced capacity for food, early dumping and late dumping. A moderately reduced capacity was regarded as being able to take one-half of what the patient would normally expect to eat at a meal and severe as one third or less. A record was made of those with a reduced capacity who showed discomfort or vomiting if the amount was exceeded. Early dumping consisted of weakness, fainting, sweating and palpitation 10-20 min utes after food. Those with late dumping had similar symptoms occurring about 30-60 min after the end of the meal.

Persistent diarrhoea was described as moderate if there were up to 3 loose stools a day and as severe if more. All of the 9 patients with diarrhoea had 24-hour faecal fat estimations and also as many of the other patients who were willing (total 158). A faecal fat output 6 g/day-12 g/day was regarded as a moderate steatorrhoea and above 12 g/day as severe.

Iron deficiency Full blood count incl uded blood picture, serum iron and total iron binding capacity (TIBC). Iron defi ciency was defined as an iron saturation (serum iron/total iron binding capacity ) below 16%.

Vitamin B12 deficiency Vitamin B12 deficiency was diagnosed when two separated bioassays repeated one month apart showed a value of less than 110 pmol/L.

Vitamin D deficiency Serum calcium, phosphate and alkaline phos phatase. The first sign was a rising serum alkaline phosphatase estimation. If this was found, liver function tests were done to exclude a hepatic cause. Other causes such as Paget’s disease, a recent fracture or bony secondaries were excl uded. A 24 h urinary calcium output below 2 mmol/24 h supported the diagnosis[2]. A therapeutic trial of calcium and vitamin D was then given as a diagnostic measure and a sustained fall in serum alkaline phosphatase levels gave confirmation of the diagnosis. Calcium and vitamin D BPC tablets calcium lactate 300 mg, calcium phosphate 150 mg, calciferol 12.5 μg), were given in a dose of 2 tablets, 4 times a day, and the dose was reduced to 2 tablets, 3 times a day when the serum alkaline phospha tase levels fell to normal.

Osteoporosis Until 1989 the right second metacarpal had been X-rayed and measurements taken from the X-ray of the second right metacarpal we re used to calculate the Exton-Smith Index:

Math 1

where T is the thickness of the bone, M is the medullary thickness at the mid-point and L is the overall length[3].

After 1989 dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) became available and was used to screen the remaining population. Only males were chosen because by then, all the female patients were postmenopausal, introducing another potential factor for osteoporotic changes.

Statistics Statistical analysis was done using the Student t test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

At the first follow-up consultation in this study 66 (29%) of the 227 patients had a moderate and 15 (7%) a severe loss of weight. 107 (47%) patients complaine d of a reduced capacity for food, which was severe in 41 (18%)

Early dumping was diagnosed in 39 (17%) and late dumping in 7 (3%). Persistent d iarrhoea occurred in 9 of the 186 Billroth II patients (being severe in 1) but in none of the 41 with a Billroth I gastrectomy. The difference was not signifi cant (Fisher’s exact test P = 0.2089). Five of these 9 patients had moderate and 2 severe steatorrhoea.

Moderate steatorrhoea was found after both operations [Billroth I, 9 (24%) of 37; Billroth II, 14 (12%) of 121; not significant, P = 0.2292].

However, severe steatorrhoea only occurred after the Billroth II procedure [32 (26%) of 121, this was significantly different from the zero incidence in the Billroth I group, P < 0.0001].

Iron deficiency. The first sign was a rising TIBC, which often preceded a fall in serum iron by several months. Actual iron-deficient anaemia developed about 6 months later.

Ferrous gluconate was found to be well tolerated and the patients were given 300 mg thrice daily until the iron deficiency was corrected and then a maintenance dose of 300mg daily.

The prevalence of iron deficiency is shown in Table 1. In the men the prevalence was significantly higher in those showing weight loss (P < 0.02) or reduced capacity for food (P < 0.05), but these differences were not seen in the women.

Vitamin B12 deficiency In most patients a fall in serum B12 concentration preceded any macrocytosis, neutrophil shift or anaemia. Patients were treated by intramuscular injections of 1000 μg hydroxocobalamin in alternate months. The prevalence in the remaining population is shown in Table 1. It can be seen that iron deficiency occurred much earlier than B12 deficiency, appearing in many patients during the first 10 years after operation. Vitamin B12 deficiency developed mostly 10-20 years after operation and its prevalence slowly increased to equal that of iron deficiency by the end of 25-30 years, when approximately 70% of men and 90% of women had developed either iron or B12 deficiency, the deficiencies being combined in 51% and 70%, respectively.

Vitamin D deficiency Vitamin D deficiency occurred in 7.5% of Billroth II and 7.3% of Billroth I gastrectomies and was predominantly a problem of female patients. (F:M = 19%:4%). It became apparent in many patients durin g the first 10 years after operation (Table 1). Of those investigated, 50% had severe and 28% moderate steatorrhoea as compared with 20% and 14% respectively for the whole series.

Osteoporosis Osteoporotic changes in excess of normal ageing we re seen in 24%, 20% and 22% of men and in 35%, 51% and 86% of women in 1969, 1974 and 1982, respectively. None of these had evidence of vitamin D deficiency. These measurements, however, were not sensitive enough to monitor any treatment over a short term[4].

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry was used in 16 active male patients, with no evidence of vitamin D deficiency, who were still attending the clinic. Six (37.5%) were found to have reduction of bone mineral density of the lumbar spine and upper left femur of more than 2 standard deviations. Initially they were treated with a calcium supplement (microcrystalline hydroxyapatite) 16 g/day-32 g/day and calciferol 0.25 mg daily but with no response. Following this they were given intermittent cyclical etidronate 400 mg nightly for 2 weeks, followed by calcium carbonate equivalent to 500 mg calcium daily for 10 weeks. This 12-week cycle was repeated over 2 years. Only 2 patients responded with a return to within the normal range of values. So far no totally satisf actory treatment has been reported for postgastrectomy osteoporosis[5].

Billroth I versus Billroth II gastrectomies There was no s ignificant difference in overall, moderate or severe weight loss between the two operations in women (BI6/12:BII26/45, P = 0.1567). In men, although there was no significant overall difference in weight loss (BI10/24:BII37/141, P = 0.1438), significantly more patients showed a moderate weight loss after a Billroth II gastrectomy (BI1/24: BII31/141, P = 0.0491), by contrast more showed severe weight loss after a Billroth I procedure (BI9/24:BII6/141, P < 0.0001).

There was no significant difference with regards to capacity for food, early or late dumping. The difference in persistent diarrhoea was not statistically different, but in severe steatorrhoea the difference between the two operations was significant (BI0/37:BII32/121, P < 0.0001).

No difference between the two operations was found in the incidence of nutritional deficiencies.

Sex differences Women on the whole fared less well than men. They had significantly more overall weight loss (F26/45:M37/141, P = 0.0002) after a Billroth II operation. There was no significant difference in severe loss, but the difference in moderate loss was significant (F21/45:M31/141, P = 0.0021). Overall, they showed a significant difference in reduced capacity for food (F43/62: M64/165, P < 0.0001 ) and much more women showed a se verely reduced capacity (F20/62:M21/ 165, P = 0.0016). Early dumping was more common in women than in men after the Billroth II operation (F15/45:M5/141, P < 0.0001). More women complained of discomfort and vomiting, if the irreduced intake was exceeded, after a Billroth II (F15/45:M10/141, P < 0.0001). They also showed more aversions to vitamin D containing food such as butter, cream, milk and eggs. Women fared worse with regards to the incidence o f iron and vitamin B12 deficiencies and more markedly in the occurrence of vitamin D deficiency (Table 1).

Several factors[6-11] contribute to nutritional disor-ders after a gastrectomy. With the loss of the pyloric sphincter there is uncontrolled gastric emptying and the capacity for food becomes dependent on the ability of the small intestine to accommodate the meal. The rapid emptying stimulates peristalsis and there is rapid passage of food through the small intestine. Small molecules such as those of sugars and starches which are rapidly broken down in the small intes tine, produce a severe osmotic effect which leads to the drawing into the gut of extracellular fluid amounting to 2-3 litres, resulting a fall in plasma volume and rise in haematocrit. This ingress of liquid distends the gut and there may be early satiety and reduced capacity for food. When the fall in plasma volume exceeds 7%, certain patients will develop early dumping with hypotension according to their vascular tolerance (Figure 2). In other patients the rapid absorption of glucose from the intestine leads to an oversecretion of insulin followed by hypoglycaemia and the symptoms of late dumping.

The increased water content of the material en-tering the large intestine may give rise to diarrhoea unless the colon is able to absorb the fluid. The presence of undigested sugars and starch may also act as irritants. The rapid passage of food through the small intestine results in a reduced mixing with the pancreatic and intestinal enzymes. This leads to impaired digestion and absorption of proteins and fats as shown by the presence of steatorrhoea in some patients. Short circuiting of the duodenum in the Billroth II operation (Figure 1) may cause pancreatic juices to lag behind the food as manifested by the presence of severe steatorrhoea in this group.

Absorption of vitamin D is dependent on fat solubility and the combination of steatorrhoea and reduced vitamin D intake may lead to vitamin D deficiency. As mentioned many patients, especially women, develop a selective aversion to certain food, particularly sources of vitamin D: this would explain the increased incidence of vitamin D deficiency in this group.

Iron metabolism may also be impaired. The in-take of iron-containing foods may be reduced. Much of the intake is in the form of ferric iron or of iron combined with protein. Acid is needed to convert ferric iron to ferrous, acid and pepsin are needed to convert organic to inorganic iron. Both acid and pepsin are reduced by a gastrectomy. In addition, most of the iron is absorbed in the duodenum and upper jejunum.

Vitamin B12 deficiency may also develop. One factor is loss of the intrinsic factor that had been secreted by gastric mucosa removed by the gastrectomy. Rapid passage through the small intestine leads to less absorption.

Calcium absorption also occurs principally in the duodenum and upper jejunum and is impaired by intestinal hurry and loss of duodenal continuity. In addition, i the presence of steatorrhoea, calcium absorption is further impaired by the formation of insoluble calcium soaps.

As a result of all these factors, postgastrectomy patients may develop iron deficiency anaemia, vitamin B12 deficiency anaemia, vitamin D deficiency and osteomalacia, or osteoporosis in excess of normal ageing.

Conclusion This study in particular demonstrates the increasing prevalence of iron and vitamin B12 deficiency in a population after gas trectomy, reaching approximately 75% in 20-30 years. This stresses the increasing importance with passing years of regularly monitoring iron saturation and B12 levels. In addition, the increased serum alkaline phosphatase levels may indicate vitamin D deficiency and need to be investigated. Now that gastrectomy is rarely performed for peptic ulcer it is important to remember that there is s till a large number of patients who underwent gastrectomy 20-30 years ago and a re at risk of developing nutritional deficiencies.

The authors wish to thank the Pos-tragduate Medical Journal for permission to reproduce data from “A gastrectomy population : 25-30 years on” 1990;66: 450-456

Edited by Ma JY

Proofread by Miao QH

| 1. | Tovey FI, Godfrey JE, Lewin MR. A gastrectomy population: 25-30 years on. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66:450-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tovey FI, Karamanolis DG, Godfrey J, Clark CG. Post-gastrectomy nutrition: methods of outpatient screening for early osteomalacia. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr. 1985;39:439-446. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Exton-Smith AN, Millard PH, Payne PR, Wheeler EF. Pattern of development and loss of bone with age. Lancet. 1969;2:1154-1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tovey FI, Hall ML, Ell PJ, Hobsley M. Postgastrectomy osteoporosis. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1335-1337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tovey FI, Hall ML, Ell PJ, Hobsley M. Cyclical etidronate therapy and postgastrectomy osteoporosis. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1168-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | LE QUESNE LP, HOBSLEY M, HAND BH. The dumping syndrome. I. Factors responsible for the symptoms. Br Med J. 1960;1:141-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kaushik SP, Ralphs DN, Hobsley M, Le Quesne LP. Use of a provocation test for objective assessment of dumping syndrome in patients undergoing surgery for duodenal ulcer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1980;74:251-257. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Linehan IP, Weiman J, Hobsley M. The 15-minute dumping provocation test. Br J Surg. 1986;73:810-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ralphs DN, Thomson JP, Haynes S, Lawson-Smith C, Hobsley M, Le Quesne LP. The relationship between the rate of gastric emptying and the dumping syndrome. Br J Surg. 1978;65:637-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hobsley M. Dumping and diarrhoea. Br J Surg. 1981;68:681-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ebied FH, Ralphs DN, Hobsley M, Le Quesne LP. Dumping symptoms after vagotomy treated by reversal of pyloroplasty. Br J Surg. 1982;69:527-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |