Published online Apr 15, 1999. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i2.177

Revised: January 4, 1999

Accepted: February 6, 1999

Published online: April 15, 1999

- Citation: Lu YF, Zhao G, Guo CY, Jia SR, Hou YD. Vagus effect on pylorus-preserving gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol 1999; 5(2): 177-178

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v5/i2/177.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v5.i2.177

Maki and others reported in 1967 the study of a pylorus - preserving gastrectomy (PPG)[1]. It successfully prevented dumping syndrome and duodenogastric reflux, but failed in gaining proper speed of gastric emptying, thus leading to new complications such as gastric retention, etc. To inquire into this subject, we have made the following experimental studies.

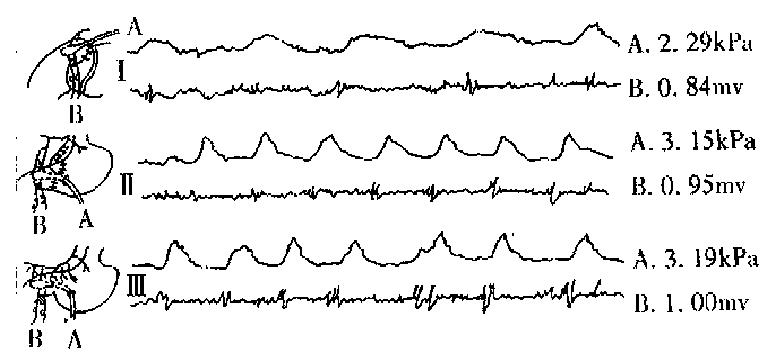

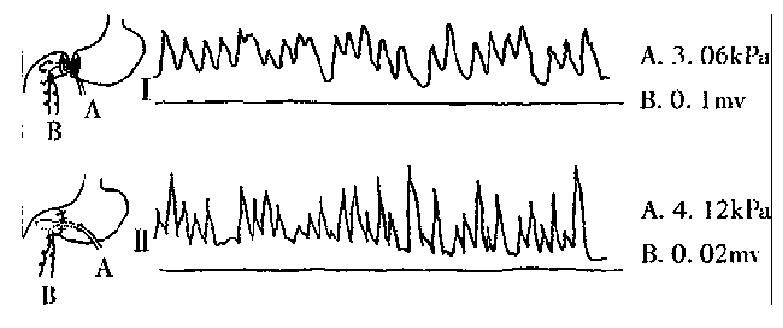

Twelve mongrel dogs of either sex weighing 15 kg to 25 kg were divided randomly into two groups 6 in each. Group A: preserving the pyloric vagus (Figure 1). Figure 1, I Make an incision on the antral wall, strip off antral m ucosa and suture seromuscular layer with its attaching vagus branches to form a small pouch in which a water bag pressure sensor had been installed. In addition, a bipolar electrode was put into the antral smooth muscle layer. Through separate transducers the pressure sensor and electrode were connected to a bichanneled physiologic kymograph for recording the intra-antral pressure curve and the electromyographic curve. Figure 1 II are the curves after pylorus and pyloric vagus preserving gastrectomy (PPVPG)[2]. Figure 1 III shows the curves of the control group. Group B: not preserving the pyloric vagus (Figure 2). According to Maki’s surgical mode, transect the antrum from the gastric body 2 cm above the pylorus and cut all the vagus branches innervating the antrum and pylorus. The rest of the procedures followed those described in Group A.

Group A. It can be seen from the figure that an action potential is immediately followed by a rhythmic stomach contraction. Figure 1 shows the curves after PPVPG, resembling those of the control group (Figure 1), demonstrating that rhythmic sphincter action is preserved by retaining the pyloric vagus. Group B. It can be seen in Figure 2, action potential of smooth muscle decreasing significantly, 8-12 times lower than that of the normal; asynchronous a ction between potential and contraction; and frequent spastic contraction of pylorus . The spastic contraction was apparently caused by the action of intramural nerve plexus or automatic rhythm of the smooth muscle, not by the action potential of the vagus.

Table 1 shows the effect of pyloric vagus on electromyogram and intraluminal pressure with the vagus preserved or resected.

In an attempt to prevent dumping syndrome and alkaline reflux gastritis as much as possible, Flynn[3], Killen et al[4] once performed resection of 50%-70% canine stomach, retaining 2 cm of the distal antrum, removing the remained antrum mucosa and anastomosing mucosa of the corpus and duodenal, then suturing the seromuscular coat. However, the operation has not been applied clinically because of its high mortality and the difficulty in stripping t he mucosa. Later, Maki continued the study and formally advanced a PPG[1], which resected most of the antrum and the corpus 2 cm from the pyloric ring and retained the remaining antrum mucosa. PPG successfully prevented dumping syndrome and duodenogastic reflux in 50 cases of gastric ulcer since its clinical application in October 1964, but failed in keeping normal gastric emptying. According to some reports, gastric retention reached 40%, lasting as long as 6 months[5]. The chief reason of gastric retention, judged by our experime ntal study, could be attributed to incision of vagus innervating pylorus, which consists of excitatory and inhibitory postganglionic fibers. The former speeds the spread of the basic electric rhythm (slow wave), facilitates the formation of an action potential which causes rhythmic contraction of stomach, and the latter, relaxes the stomach. By the coordination of the two, the stomach contracts and relaxes rhythmically. With the vagus resected, the action potential of gastric smooth muscle decreases notably, autonomous contraction of gastric smooth muscle induced by the homogenetic rhythm of smooth muscle and the intramural nerve plexus occurs. The uncontrolled spastic contraction will lead to the delay of gastric emptying as well as gastric retention. In our view, the physiological function of pyloric sphincter can not be really preserved without preserving vagus innervating pylorus. To preserve the vagus, we designed a PPVPG through a large number of experimental studies on animals[4]. This operation mainly consists of stri pping off antrum mucosa, excising the bulk of the corpus, preserving pylorus, va gus trunks, Latarjer vagus and the last two to three branches of avian claw vagus innervating the pyloric region; it has been applied clinically since January, 1988. As many as 132 cases of peptic ulcer were so treated with good results. The fact that there was not a single case of gastric retention and ulcer relapse in the follow-up survey. All these demonstrate that PPVPG was scientific enough to meet all clinical requirements. At the same time, it has proved that preserving vagus is rather important in preventing gastric retention after PPG.

Edited by Han-Ming Lu

| 1. | Maki T, Shiratori T, Hatafuku T, Sugawara K. Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy as an improved operation for gastric ulcer. Surgery. 1967;61:838-845. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Lu Y, Hoa Y, Jia S, Gao C. Experimental study of pylorus and pyloric vagus preserving gastrectomy. World J Surg. 1993;17:525-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | FLYNN PJ, LONGMIRE WP. Subtotal gastrectomy with pyloric sphincter preservation. Surg Forum. 1960;10:185-188. [PubMed] |

| 4. | KILLEN DA, SYMBAS PN. Effect of preservation of the pyloric sphincter during antrectomy on postoperative gastric emptying. Am J Surg. 1962;104:836-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nanna AN. Clinical experience of 18 cases of gastrectomy pre-serving pylorus. Shiyong Waike Zazhi. 1986;6:245-246. |