Published online Dec 14, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i46.6752

Peer-review started: October 15, 2019

First decision: November 4, 2019

Revised: November 12, 2019

Accepted: November 29, 2019

Article in press: November 29, 2019

Published online: December 14, 2019

Processing time: 59 Days and 22 Hours

The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) excludes extrapancreatic extension from the assessment of T stage and restages tumors with mesenterico-portal vein (MPV) invasion into T1-3 diseases according to tumor size. However, MPV invasion is believed to be correlated with a poor prognosis.

To analyze whether the inclusion of MPV invasion can further improve the 8th edition of the AJCC staging system for PDAC.

This study retrospectively included 8th edition AJCC T1-3N0-2M0 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy/total pancreatectomy from two cohorts and analyzed survival outcomes. In the first cohort, a total of 7539 patients in the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database was included, and in the second cohort, 689 patients from the West China Hospital database were enrolled.

Cox regression analysis showed that MPV invasion is an independent prognostic factor in both databases. In the MPV- group, all pairwise comparisons between the survival functions of patients with different stages were significant except for the comparison between patients with stage IIA and those with stage IIB. However, in the MPV+ group, pairwise comparisons between the survival functions of patients with stage IA, stage IB, stage IIA, stage IIB, and stage III were not significant. T1-3N0 patients in the MPV+ group were compared with the T1N0, T2N0, and T3N0 subgroups of the MPV- group; only the survival of MPV-T3N0 and MPV+T1-3N0 patients had no significant difference. Further comparisons of patients with stage IIA and subgroups of stage IIB showed (1) no significant difference between the survival of T2N1 and T3N0 patients; (2) a longer survival of T1N1 patients that was shorter than the survival of T2N0 patients; and (3) and a shorter survival of T3N1 patients that was similar to that of T1-3N2 patients.

The modified 8th edition of the AJCC staging system for PDAC proposed in this study, which includes the factor of MPV invasion, provides improvements in predicting prognosis, especially in MPV+ patients.

Core Tip: The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma restages tumors with mesenterico-portal vein (MPV) invasion into T1-3 diseases according to tumor size. However, the survival analysis indicated that these patients have similar prognoses. The modified staging system, which includes the factor of MPV invasion, provides improvements in predicting prognosis.

- Citation: Chen HY, Wang X, Zhang H, Liu XB, Tan CL. Mesenterico-portal vein invasion should be an important factor in TNM staging for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Proposed modification of the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(46): 6752-6766

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i46/6752.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i46.6752

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is still an important cause of cancer-related death, with a mortality rate of approximately 13/100000[1]. Radical surgical resection is the only hope to cure pancreatic cancer, but the postoperative five-year survival rate is only 10%-20%. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system is widely used to evaluate the prognosis of pancreatic cancer patients after resection and to determine further treatment. The 8th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual was published in 2016. The T stage of pancreatic cancer was evaluated according to tumor diameter and invasion of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), common hepatic artery (CHA), or celiac artery (CA). N stage was divided into groups with different prognoses according to the number of positive lymph nodes: 0, 1-3, and more than 4[2]. Compared with the 7th edition, extrapancreatic extension was excluded from the assessment of T stage. Extrapancreatic extension was defined as tumors that "extend beyond the pancreas" with the involvement of extrapancreatic structures. It is generally believed to involve the following structures: The ampulla of Vater, duodenum, extrahepatic biliary ducts and gallbladder, distal stomach, transverse colon and hepatic flexure, gastroduodenal artery (GDA), pan-creaticoduodenal artery, mesenterico-portal vein (MPV), omentum, and accessory structures[3]. Since the definition of extrapancreatic extension is complex and involves many types of tissues, it is difficult to judge extrapancreatic extension, and the implementation in each center is quite different[4-6]. Moreover, the invasion of different tissue types represents different biological behavior of tumors, so the effect of the 7th edition of the AJCC staging system in clinical practice has been questioned. The 8th edition of the AJCC pancreatic cancer staging system improved the staging system by replacing the factor of pancreatic invasion with a diameter greater than 4 cm. However, MPV invasion is believed to indicate a poor prognosis for pancreatic cancer patients[7-9]. The 8th edition of the AJCC pancreatic cancer staging system completely negates this factor.

In the present study, we collected data from pancreatic cancer patients undergoing radical pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) and total pancreatectomy (TP) from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database and the West China Hospital database, with an aim to assess the impact of MPV invasion on the prognosis of patients and to analyze whether the inclusion of MPV invasion can further improve the 8th edition of the AJCC pancreatic cancer staging system.

Based on the SEER database (1975-2016), we retrospectively included patients with pathologically confirmed ductal adenocarcinoma (ICD-O-3 histologic code as 8140 or 8500) of the head of the pancreas (ICD-10 code of primary site as C25.0) after PD/TP (surgery code as 35-37 or 70). The 8th edition of the cancer staging system was determined by the following data in the database[3]: Collaborative stage (CS) tumor size (2004+), CS extension (2004+), regional nodes examined (1988+), regional nodes positive (1988+), and CS Mets at DX (2004+). CS tumor size and CS extension data describe the diameters and extensions of the primary tumors that contributed to T classification, and CS Mets at DX represented the status of distant metastasis. Patients (1) Who did not report the data mentioned above; (2) Who had 5 or fewer lymph nodes examined or; and (3) With tumors that invaded the SMA and/or CA (T4) or with distant metastasis (M1) were excluded.

In this study, patients with tumors with CS extension[3] data labeled "540" were defined as the MPV+ group, and all the other patients were defined as the MPV- group.

Between 2013 and 2017, the clinicopathological data of patients who underwent PD or TP at West China Hospital with pathologically confirmed PDAC (stage T1-3N0-2M0) were retrospectively retrieved from the West China Hospital database, a prospective surgical database. Since the pathologic stage was evaluated after the first surgery, only tumors that were considered resectable at the initial diagnosis were included in this cohort. No patient received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The follow-up deadline was March 30, 2019. Patients whose clinical examination and pathological results, especially the circumferential margin[7], were not reported were excluded from this study (n = 27). Similarly, we removed patients in whom the number of lymph nodes examined was 5 or less in pathological reports (n = 69). Positive margins (R1 resection) were defined as microscopic evidence of tumor ≤ 1 mm from the resection margins.

Only patients with microscopic MPV invasion were defined as the MPV+ group. Patients who did not require MPV resection and those who underwent PD combined with MPV resection but the pathology indicated that the tumor did not invade the MPV were defined as the MPV- group.

The data of this cohort were approved by the West China Hospital Review Board under registration number 2019 (124).

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL, United States), and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Numeric variables (such as age) are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean and were compared using ANOVA followed by the least significant difference (LSD) test. Nominal data (sex, stage, grade, etc.) are reported in the form of frequencies and percentages and were compared using χ² tests or Fisher’s exact tests. Cox regression was adopted to evaluate whether MPV invasion is an independent prognostic factor. The multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis was done using a stepwise (Wald) approach. Survival outcomes were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and are presented in the form of the medians of survival and survival functions. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates (± standard error) were retrieved from the survival tables. Survival functions were compared using the log-rank test, and when the null hypothesis was accepted, comparisons of the 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were performed with the z-test.

Since the extent of local infiltration (CS extension) was not reported before 2004 and in the new cases of 2016, these patients were excluded from the study. A total of 7539 patients from the SEER database were enrolled in this study. The baseline data are shown in Table 1. The probabilities of MPV invasion were different between different T stages (P = 0.000, LSD T1 vs T2 P = 0.008, T2 vs T3 P = 0.000). There was no significant difference in the lymph node metastasis rate (P = 0.161) or tumor differentiation (P = 0.605) between the MPV- and MPV+ groups. After the verification of the proportional hazard assumption (Supplementary Figure 1), univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were utilized to examine whether MPV invasion is an independent factor for predicting prognosis. Cox regression analyses showed that MPV invasion was a prognostic factor which was independent from sex, T stage, and N stage (univariate P = 0.002, multivariate P = 0.003, Table 2).

| Characteristic | SEER database | West China Hospital database | ||||

| MPV- group | MPV+ group | P value | MPV- group | MPV+ group | P value | |

| Sample size, n | 6825 | 714 | 579 | 110 | ||

| Sex | 0.041a | 0.353 | ||||

| Male | 3458 (50.7) | 333 (46.6) | 368 (63.6) | 75 (68.2) | ||

| Female | 3367 (49.3) | 381 (53.4) | 211 (36.4) | 35 (31.8) | ||

| Age at diagnosis (± SEM) | 66.4 (± 0.13) | 65.4 (± 0.38) | 0.019a | 58.4 (± 0.41) | 58.35 (± 0.88) | 0.998 |

| Tumor diameter | 0.000a | 0.003a | ||||

| ≤ 2 cm | 1232 (18.1) | 62 (8.7) | 130 (22.5) | 12 (10.9) | ||

| > 2 cm but ≤ 4 cm | 4377 (64.1) | 482 (67.5) | 373 (64.4) | 73 (66.4) | ||

| > 4 cm | 1216 (17.8) | 170 (23.8) | 76 (13.1) | 25 (22.7) | ||

| Positive lymph nodes | 0.161 | 0.001a | ||||

| 0 | 1900 (27.8) | 214 (30.0) | 345 (59.6) | 46 (41.8) | ||

| 1-3 | 2893 (42.4) | 311 (43.6) | 195 (33.7) | 48 (43.6) | ||

| ≥ 4 | 2032 (29.8) | 189 (26.5) | 39 (6.7) | 16 (14.5) | ||

| AJCC 8th stage | 0.000a | 0.000a | ||||

| IA | 500 (7.3) | 22 (3.1) | 89 (15.4) | 4 (3.6) | ||

| IB | 1162 (17.0) | 19 (20.9) | 219 (37.8) | 31 (28.2) | ||

| IIA | 238 (3.5) | 43 (6.0) | 37 (6.4) | 11 (10.0) | ||

| IIB | 2893 (42.4) | 311 (43.6) | 195 (33.7) | 45 (43.6) | ||

| III | 2032 (29.8) | 189 (26.5) | 39 (6.7) | 16 (14.5) | ||

| Perineural invasion | N/A | 0.016a | ||||

| Absent | N/A | N/A | 165 (28.3) | 19 (17.3) | ||

| Present | N/A | N/A | 415 (71.7) | 91 (82.7) | ||

| Intravascular tumor emboli | N/A | 0.971 | ||||

| Absent | N/A | N/A | 494 (85.3) | 94 (85.5) | ||

| Present | N/A | N/A | 85 (14.7) | 16 (14.5) | ||

| Grade1 | 0.605 | 0.984 | ||||

| Well differentiated | 632 (9.3) | 59 (8.3) | 5 (0.9) | 1 (1.0) | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 3397 (49.8) | 314 (44.0) | 215 (38.1) | 37 (37.4) | ||

| Poorly/undifferentiated | 2489 (36.5) | 251 (35.1) | 344 (61.0) | 61 (61.6) | ||

| Unknown | 307 (4.5) | 90 (12.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Margin status2 | N/A | 0.000a | ||||

| R0 | N/A | N/A | 427 (73.7) | 61 (55.5) | ||

| R1 | N/A | N/A | 152 (26.3) | 49 (44.5) | ||

| R2 | N/A | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Univariate | SEER database | West China Hospital database | ||||

| Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.000 | Reference | 1.000 | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.931 | (0.879, 0.987) | 0.017a | 0.861 | (0.709, 1.046) | 0.132 |

| Tumor diameter | 0.000a | 0.000a | ||||

| ≤ 2 cm (T1) | 1.000 | Reference | 1.000 | Reference | ||

| > 2 cm but ≤ 4 cm (T2) | 1.375 | (1.267, 1.492) | 0.000a | 1.466 | (1.145, 1.878) | 0.002a |

| > 4 cm (T3) | 1.796 | (1.629, 1.982) | 0.000a | 2.466 | (1.789, 3.397) | 0.000a |

| Positive lymph nodes | 0.000a | 0.000a | ||||

| 0 (N0) | 1.000 | Reference | 1.000 | Reference | ||

| 1-3 (N1) | 1.527 | (1.419, 1.644) | 0.000a | 1.676 | (1.378, 2.039) | 0.000a |

| > 4 (N2) | 1.940 | (1.791, 2.100) | 0.000a | 2.466 | (1.774, 3.429) | 0.000a |

| MPV invasion | 1.170 | (1.059, 1.293) | 0.002a | 1.708 | (1.352, 2.159) | 0.000a |

| Multivariate | SEER database | West China Hospital database | ||||

| Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.000 | Reference | ||||

| Female | 0.937 | (0.887, 0.989) | 0.018a | |||

| Tumor diameter | 0.000a | 0.000a | ||||

| T1 | 1.000 | Reference | 1.000 | Reference | ||

| T2 | 1.299 | (1.203, 1.404) | 0.000a | 1.361 | (1.060, 1.746) | 0.015a |

| T3 | 1.611 | (1.468, 1.768) | 0.000a | 2.079 | (1.500, 2.880) | 0.000a |

| Positive lymph nodes | 0.000a | 0.000a | ||||

| N0 | 1.000 | Reference | 1.000 | Reference | ||

| N1 | 1.454 | (1.358, 1.557) | 0.000a | 1.573 | (1.290, 1.916) | 0.000a |

| N2 | 1.842 | (1.710, 1.984) | 0.000a | 2.127 | (1.523, 2.971) | 0.000a |

| MPV invasion | 1.178 | (1.071, 1.290) | 0.000a | 1.423 | (1.120, 1.807) | 0.004a |

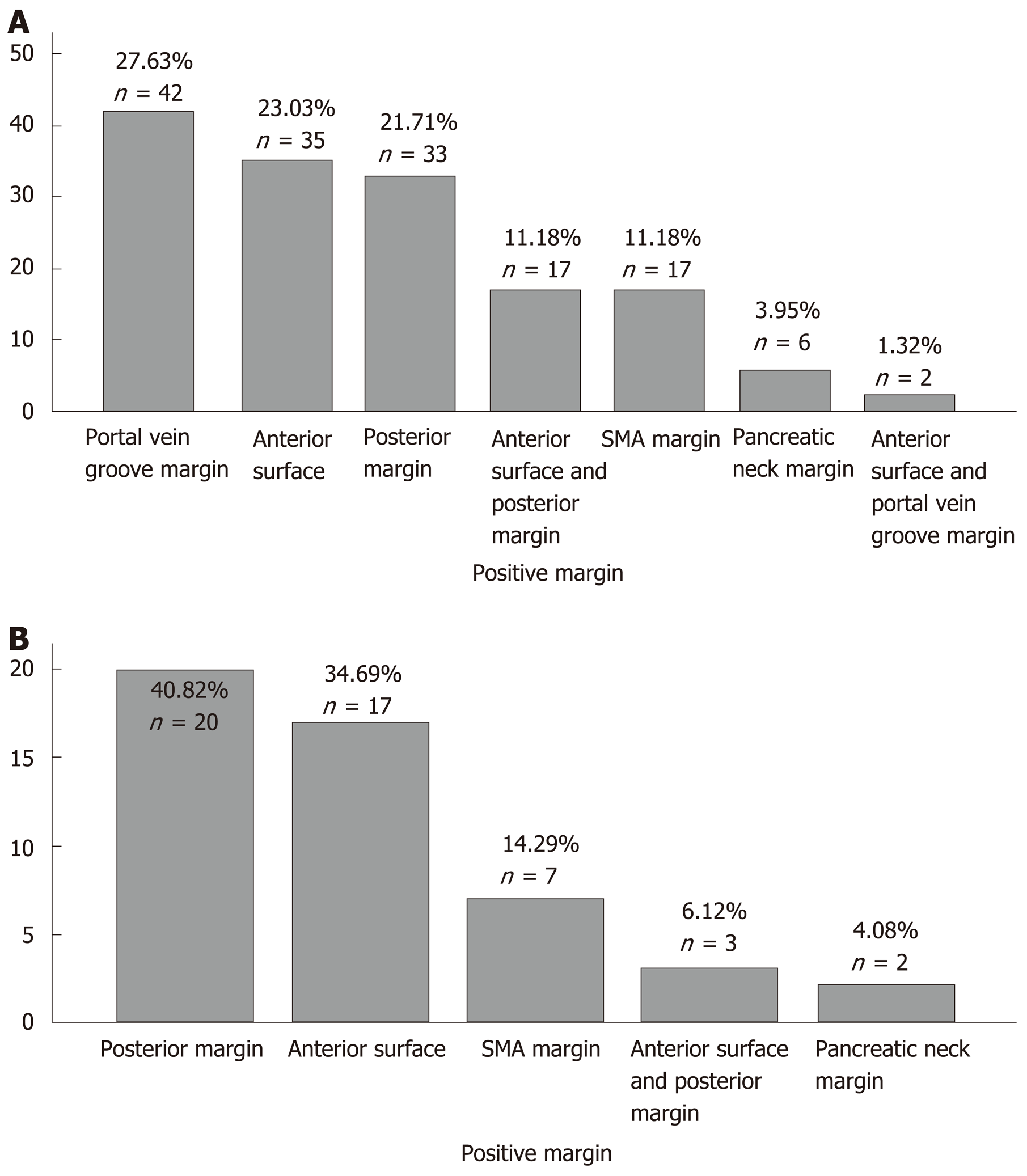

From the West China Hospital database, we included 689 patients with PDAC after PD/TP (Table 1). In the West China Hospital database, the proportion of patients with positive lymph node(s) was significantly lower compared to that of the SEER database (298/689 vs 5425/7539, P = 0.000). The probability of MPV invasion was associated with a higher T stage (total P = 0.003, T1 vs T2 P = 0.024, T2 vs T3 P = 0.037). Patients with MPV invasion were more likely to have lymph node metastasis (P = 0.001). The MPV+ group had a higher incidence of perineural invasion (P = 0.016) and a similar proportion of intravascular tumor emboli (P = 0.971) compared with the MPV- group. The proportion of R0 resections in the MPV+ group was lower than that in the MPV- group (55.5% vs 73.7%, P = 0.000). Univariate (P = 0.000, Table 2) and multivariate (P = 0.004) Cox regression analyses showed that MPV invasion was an independent prognostic factor. The frequencies of positive margins are listed in Figure 1.

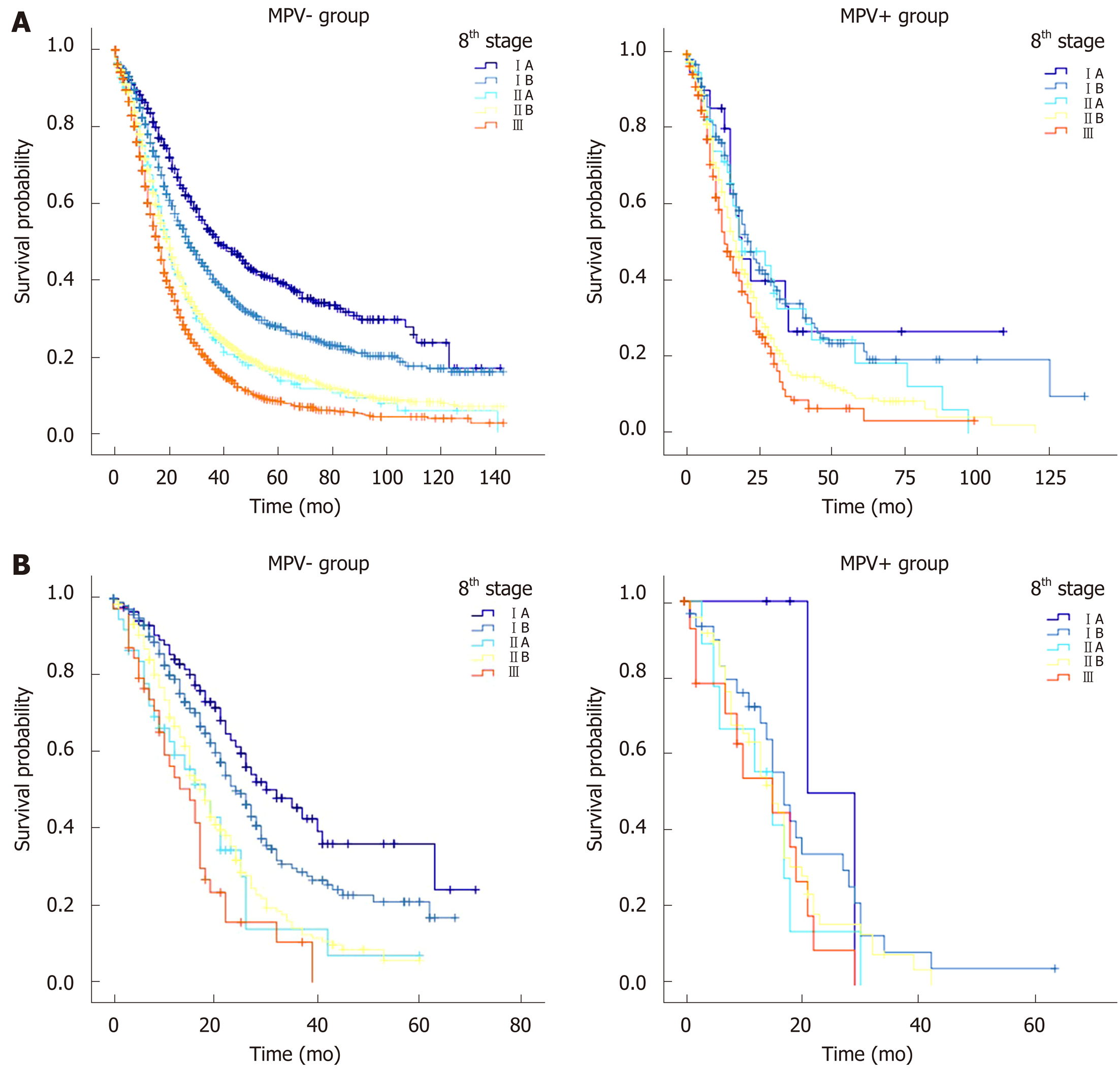

In the SEER database, the MPV- group was divided into five subgroups according to the 8th edition of the AJCC staging system to compare their prognoses. There were statistically significant differences in survival between patients with stage IA vs patients with stage IB [median survival time (MST) 38 mo vs 27 mo, P = 0.000], patients with stage IB vs patients with stage IIA (MST 27 mo vs 20 mo, P = 0.000), and patients with stage IIB vs patients with stage III (MST 20 mo vs 16 mo, P = 0.000), but there was no statistically significant difference in survival between patients with stage IIA and those with stage IIB (MST 20 mo vs 20 mo, P = 0.622). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates of patients with stage IIA and stage IIB were further compared: 69.8% vs 68.7%, 24.7% vs 26.3%, and 13.4% vs 15.9%, respectively (P > 0.05 for all). The MPV+ group was also divided into five subgroups according to the AJCC stage and compared with each other. The MSTs of patients with stages IA, IB, IIA, IIB, and III were 19, 22, 19, 17, and 13 mo, respectively. All pairwise comparisons of the survival functions of patients with different stages were not statistically significant (P > 0.05 for all). When comparing the 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates, only the 3-year survival rates of patients with stage IIA vs patients with stage IIB (32.8% vs 15.3%, P = 0.047) and the 1-year survival rates of patients with stage IIB vs patients with stage III (63.6% vs 53.1%, P = 0.029) showed statistically significant differences, while the survival rates of patients with other stages showed no significant difference (Table 3 and Figure 2A).

| SEER database | West China Hospital database | |||

| MPV- group | MPV+ group | MPV- group | MPV+ group | |

| Stage IA | ||||

| Median survival | 38 (± 3.6) | 19 (± 3.4) | 32 (± 5.3) | 21 |

| 1-yr survival rate | 84.7% (± 1.7%) | 85.7% (± 7.6%) | 84.2% (± 4.0%) | 100.0% |

| 3-yr survival rate | 51.7% (± 2.5%) | 26.8% (± 10.9%) | 45.4% (± 6.6%) | 0.0% (±0.0%) |

| 5-yr survival rate | 39.4% (± 2.7%) | 26.8% (± 10.9%) | 36.0% (± 7.1%) | 0.0% (± 0.0%) |

| Stage IB | ||||

| Median survival | 27 (± 1.3) | 22 (± 2.3) | 24 (± 1.6) | 17 (± 2.3) |

| 1-yr survival rate | 78.0% (± 1.3%) | 76.6% (± 3.7%) | 79.0% (± 2.9%) | 72.5% (± 8.3%) |

| 3-yr survival rate | 40.1% (± 1.6%) | 34.1% (± 4.6%) | 27.9% (± 3.8%) | 8.55% (± 5.7%) |

| 5-yr survival rate | 27.6% (± 1.6%) | 23.7% (± 4.4%) | 20.9% (± 4.0%) | 4.35% (± 4.2%) |

| Stage IIA | ||||

| Median survival | 20 (± 1.1) | 19 (± 6.6) | 18 (± 3.7) | 15 (± 3.7) |

| 1-yr survival rate | 69.8% (± 3.1%) | 71.6% (± 7.3%) | 59.3% (± 8.5%) | 55.6% (± 16.6%) |

| 3-yr survival rate | 24.7% (± 3.1%) | 32.8% (± 8.5%) | 13.7% (± 8.4%) | 0.0% (± 0.0%) |

| 5-yr survival rate | 13.4% (± 2.7%) | 18.4% (± 8.1%) | 6.95% (± 6.4%) | 0.0% (± 0.0%) |

| Stage IIB | ||||

| Median survival | 20 (± 0.5) | 17 (± 1.1) | 18 (± 1.0) | 15 (± 4.8) |

| 1-yr survival rate | 68.7% (± 0.9%) | 63.6% (± 2.8%) | 66.7% (± 3.5%) | 63.3% (± 7.1%) |

| 3-yr survival rate | 26.3% (± 0.9%) | 15.3% (± 2.3%) | 14.1% (± 3.1%) | 7.95% (± 4.3%) |

| 5-yr survival rate | 15.9% (± 0.8%) | 9.25% (± 2.1%) | 5.65% (± 2.9%) | 0.0% (± 0.0%) |

| Stage III | ||||

| Median survival | 16 (± 0.4) | 13 (± 1.2) | 15 (± 2.8) | 15 (± 4.8) |

| 1-yr survival rate | 60.0% (± 1.1%) | 53.1% (± 3.9%) | 53.3% (± 8.4%) | 53.9% (± 14.1%) |

| 3-yr survival rate | 17.6% (± 1.0%) | 8.65% (± 2.6%) | 10.4% (± 6.1%) | 0.0% (± 0.0%) |

| 5-yr survival rate | 8.15% (± 0.8%) | 6.55% (± 2.4%) | 0.0% (± 0.0%) | 0.0% (± 0.0%) |

| IA vs IB | ||||

| Survival function | P = 0.000a | P = 0.917 | P = 0.044a | P = 0.382 |

| 1-yr survival rate | P = 0.002a | P = 0.282 | P = 0.293 | |

| 3-yr survival rate | P = 0.000a | P = 0.537 | P = 0.022a | P = 0.136 |

| 5-yr survival rate | P = 0.000a | P = 0.792 | P = 0.064 | P = 0.306 |

| IB vs IIA | ||||

| Survival function | P = 0.000a | P = 0.486 | P = 0.003a | P = 0.264 |

| 1-yr survival rate | P = 0.015a | P = 0.541 | P = 0.028a | P = 0.363 |

| 3-yr survival rate | P = 0.000a | P = 0.893 | P = 0.124 | P = 0.136 |

| 5-yr survival rate | P = 0.000a | P = 0.565 | P = 0.064 | P = 0.306 |

| IIA vs IIB | ||||

| Survival function | P = 0.622 | P = 0.136 | P = 0.523 | P = 0.500 |

| 1-yr survival rate | P = 0.733 | P = 0.306 | P = 0.421 | P = 0.670 |

| 3-yr survival rate | P = 0.620 | P = 0.047a | P = 0.964 | P = 0.066 |

| 5-yr survival rate | P =0.375 | P = 0.272 | P = 0.853 | |

| IIB vs III | ||||

| survival function | P = 0.000a | P = 0.053 | P = 0.033a | P = 0.418 |

| 1-yr survival rate | P = 0.000a | P = 0.029a | P = 0.141 | P = 0.552 |

| 3-yr survival rate | P = 0.000a | P = 0.054 | P = 0.589 | P = 0.066 |

| 5-yr survival rate | P = 0.000a | P =0.397 | P = 0.053 | |

In the West China Hospital database, there were statistically significant survival function differences in the MPV- group: Patients with stage IA vs patients with stage IB (MST 32 mo vs 24 mo, P = 0.044), patients with stage IB vs patients with stage IIA (MST 24 mo vs 18 mo, P = 0.003), and patients with stage IIB vs patients with stage III (MST 18 mo vs 15 mo, P = 0.033). There was no significant difference in survival functions (MST 18 mo vs 18 mo) or survival rates between patients with stage IIA and those with IIB (P > 0.05 for all). There were no statistically significant differences in survival functions or survival rates between patients with different stages in the MPV+ group (Table 3 and Figure 2B).

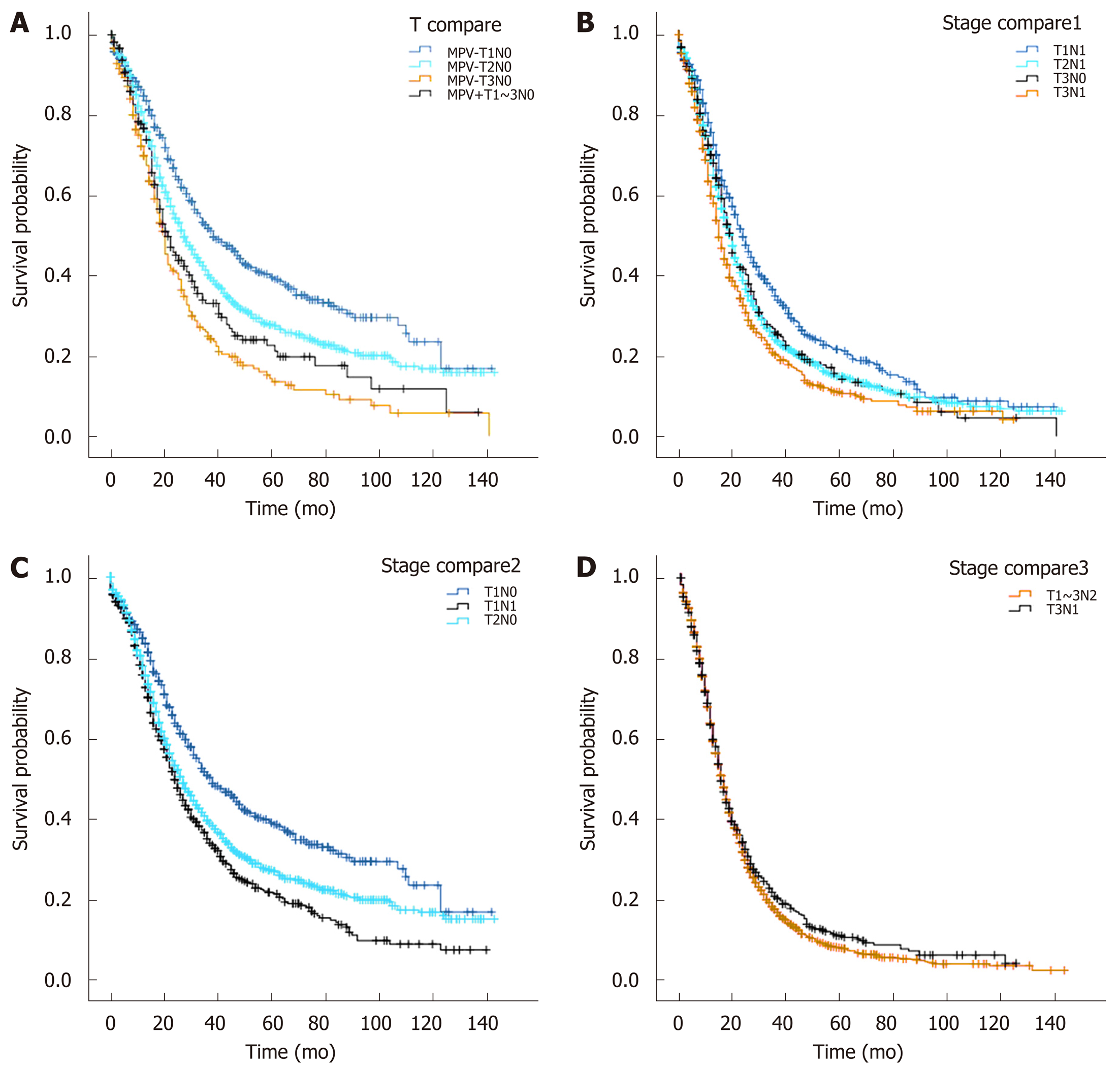

There were statistically significant differences in the survival of T1-3N0 patients with MPV invasion compared with that of T1N0 (MPV+T1-3N0 MST 21 mo vs MPV-T1N0 MST 38 mo, P = 0.000, Figure 3A) and T2N0 (MPV+T1-3N0 MST 21 mo vs MPV-T2N0 MST 27 mo, P = 0.026) patients without MPV invasion. There was no statistically significant difference in the survival function between T1-3N0 patients with MPV invasion and T3N0 patients without MPV invasion (MPV+T1-3N0 MST 21 mo vs MPV-T3N0 MST 20 mo, P = 0.073).

There was no significant difference between the survival functions of patients in the T2N1 and T3N0 subgroups (T2N1 MST 20 mo vs T3N0 MST 20 mo, P = 0.956, Figure 3B). The survival of patients in the T1N1 subgroup (MST 24 mo, vs T3N0 P = 0.010, vs T2N1 P = 0.000, Figure 3B) was longer than that in the T3N0 and T2N1 subgroups. When the survival function of patients in the T1N1 subgroup (MST 24 mo) was compared with that of patients in the T1N0 (MST 38 mo, vs T1N1 P = 0.000) and T2N0 (MST 27 mo, vs T1N1 P = 0.006) subgroups, log-rank tests showed significant differences between the three groups (Figure 3C). The survival of patients in the T3N1 subgroup (MST 15 mo, vs T3N0 P = 0.021, vs T2N1 P = 0.001, Figure 3B) was shorter than that of the T3N0 and T2N1 subgroups, while there was no difference in the survival functions between patients in the T3N1 subgroup and those in the T1-3N2 subgroup (T3N1 MST 15 mo vs T1-3N2 MST 16 mo, P =0.193, Figure 3D).

Based on the results of the previous analysis, we recommend the modified stage scheme shown in Table 4. Harrell concordance indexes were calculated for the 8th T stage and modified T stage in patients with N0 diseases. The Harrell concordance indexes for the N0 tumors in the SEER database using 8th T staging and modified T staging were 0.552 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.536 to 0.567] and 0.556 (95%CI: 0.540 to 0.571), respectively, and for patients with N0 diseases in the West China Hospital database, the Harrell concordance indexes were 0.578 (95%CI: 0.541 to 0.615) using the 8th T staging and 0.584 (95%CI: 0.545 to 0.623) using the modified T staging. For the entire databases, the Harrell concordance indexes of the 8th edition AJCC stage were 0.572 (95%CI: 0.564 to 0.580) in the SEER database and 0.602 (95%CI: 0.575 to 0.630) in the West China Hospital database, while those of the modified stage were 0.578 (95%CI: 0.570 to 0.586) in the SEER database and 0.620 (95%CI: 0.593 to 0.647) in the West China Hospital database.

| AJCC staging of pancreatic cancer (8th edition) | Stage |

| Primary tumor size and extension (T) | |

| T1: Tumor ≤ 2 cm in the greatest dimension, without involvement of the CA, SMA, and CHA. | IA: T1N0M0 |

| IB: T2N0M0 | |

| T2: Tumor > 2 cm and ≤ 4 cm in the greatest dimension, without involvement of the CA, SMA, and CHA. | IIA: T3N0M0 |

| IIB: T1-3N1M0 | |

| T3: Tumor > 4 cm in the greatest dimension, without involvement of the CA, SMA, and CHA. | III: (1) TxN2M0; |

| T4: Tumor involves the CA, SMA, or CHA, regardless of size. | (2) T4NxM0 |

| Regional lymph node (N) | IV: TxNxM1 |

| N0: No positive regional lymph node | |

| N1: 1-3 positive regional lymph nodes | |

| N2: 4 or more positive regional lymph nodes | |

| Distant metastasis (M) | |

| M0: No distant metastasis | |

| M1: Distant metastasis | |

| Modified staging of pancreatic cancer | |

| Primary tumor size and extension (T) | |

| T1: Tumor ≤ 2 cm in the greatest dimension, without involvement of the CA, SMA, CHA, and MPV | IA: T1N0M0 |

| IB: T2N0M0 | |

| T2: Tumor > 2 cm and ≤ 4 cm in the greatest dimension, without involvement of the CA, SMA, CHA, and MPV | IIA: T1N1M0 |

| IIB: T3N0M0; | |

| T3: Tumor involves the MPV, or > 4 cm in the greatest dimension, without involvement of the CA, SMA, and CHA | T2N1M0 |

| III: (1) T3N1M0; | |

| T4: Tumor involves the CA, SMA, or CHA, regardless of size | (2) TxN2M0; |

| Regional lymph node (N) | (3) T4NxM0 |

| N0: No positive regional lymph node | IV: TxNxM1 |

| N1: 1-3 positive regional lymph nodes | |

| N2: 4 or more positive regional lymph nodes | |

| Distant metastasis (M) | |

| M0: No distant metastasis | |

| M1: Distant metastasis | |

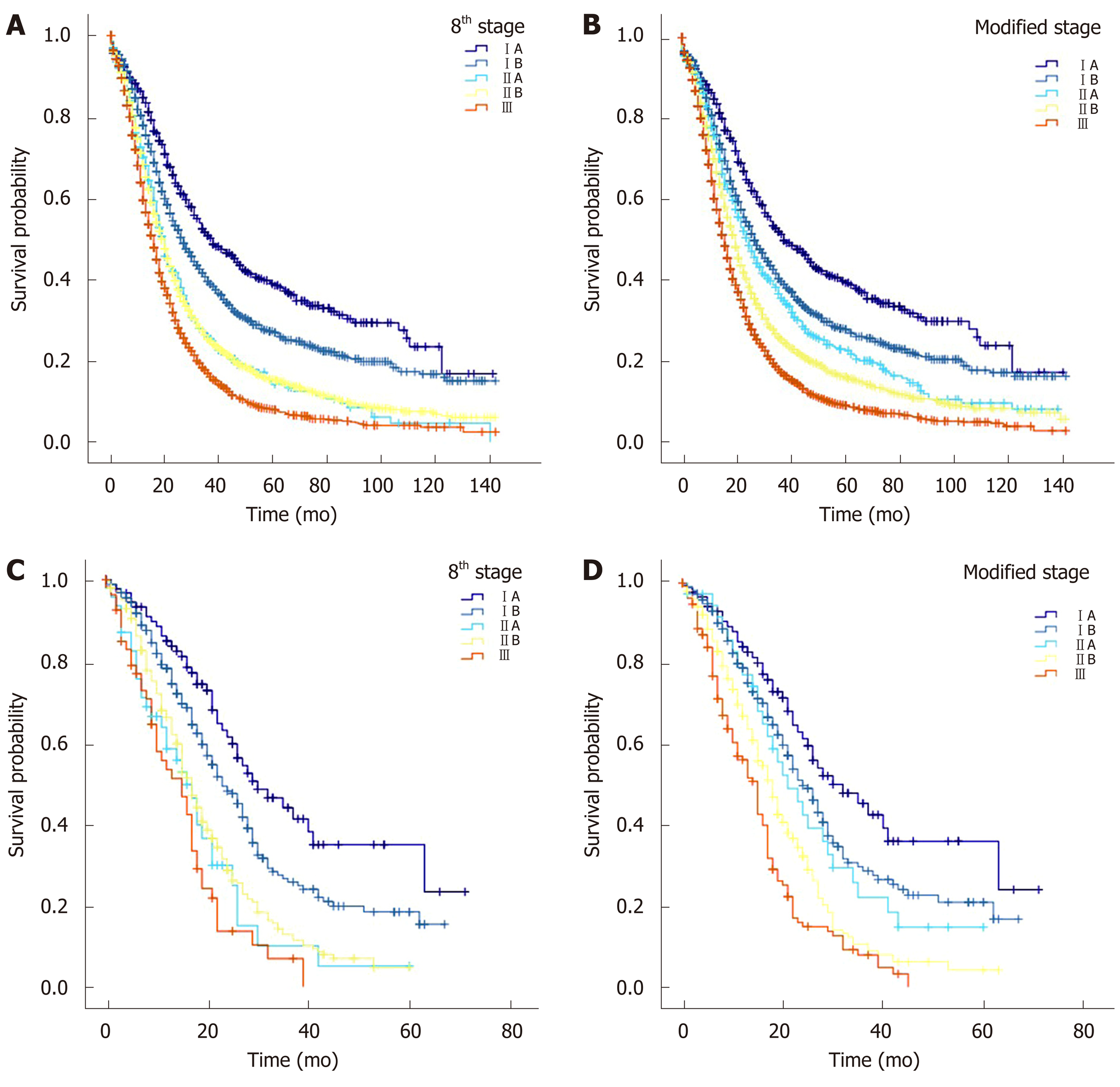

According to data of the SEER cohort, there were statistically significant differences in survival times between patients with modified T stages (the MSTs of T1, T2, and T3 were 28 mo, 20 mo, and 16 mo, respectively, P < 0.05 for all, Table 5B). The MSTs of patients with modified stages IA, IB, IIA, IIB, and III were 38, 27, 25, 20, and 16 mo, respectively, with significant and clinical differences between the stages (Table 5D and Figure 4B).

| Stage | SEER database | West China Hospital database | ||||||

| Median survival | 1-yr survival rate, % (±%) | 3-yr survival rate, % (±%) | 5-yr survival rate, % (±%) | Median survival | 1-yr survival rate, % (±%) | 3-yr survival rate, % (±%) | 5-yr survival rate, % (±%) | |

| Prognostic comparison of different 8th edition AJCC T classifications | ||||||||

| AJCC T1 | 27 (± 1.1) | 78.7 (± 1.2) | 39.7 (± 1.5) | 27.0 (± 1.5) | 25 (± 2.2) | 82.6 (± 3.3) | 32.9 (± 4.8) | 24.4 (± 4.9) |

| AJCC T2 | 20 (± 0.3) | 68.9 (± 0.7) | 26.0 (± 0.7) | 16.1 (± 0.7) | 19 (± 0.9) | 72.0 (± 2.2) | 21.5 (± 2.4) | 11.4 (± 2.2) |

| AJCC T3 | 15 (± 0.5) | 61.7 (± 1.4) | 18.7 (± 1.2) | 9.9 (± 1.0) | 15 (± 1.6) | 53.5 (± 5.3) | 10.4 (± 4.1) | 3.1 (± 2.8) |

| T1 vs T2 | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.002a | P = 0.008a | P = 0.034a | P = 0.016a |

| T2 vs T3 | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.001a | P = 0.019a | P = 0.020a |

| Prognostic comparison of different modified T classifications | ||||||||

| Modified T1 | 28 (± 1.2) | 78.7 (± 1.2) | 41.1 (± 1.6) | 27.8 (± 1.6) | 26 (± 2.6) | 82.6 (± 3.4) | 35.7 (± 5.1) | 26.5 (± 5.2) |

| Modified T2 | 20 (± 0.4) | 69.2 (± 0.7) | 26.6 (± 0.8) | 16.4 (± 0.7) | 21 (± 1.1) | 72.8 (± 2.4) | 21.8 (± 2.8) | 13.8 (± 2.7) |

| Modified T3 | 16 (± 0.4) | 60.5 (± 1.2) | 19.1 (± 1.0) | 10.7 (± 0.9) | 15 (± 0.8) | 61.1 (± 3.7) | 7.7 (± 2.5) | 2.6 (± 1.6) |

| T1 vs T2 | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.004a | P = 0.019a | P = 0.017a | P = 0.030a |

| T2 vs T3 | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.008a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a |

| Prognostic comparison of different 8th edition AJCC stages | ||||||||

| AJCC IA | 38 (± 3.4) | 84.8 (± 1.6) | 50.7 (± 2.5) | 38.9 (± 2.6) | 30 (± 4.6) | 84.9 (± 3.9) | 43.9 (± 6.5) | 34.8 (± 7.0) |

| AJCC IB | 27 (± 1.1) | 77.8 (± 1.2) | 39.4 (± 1.5) | 27.2 (± 1.5) | 23 (± 1.8) | 78.2 (± 2.7) | 25.6 (± 3.6) | 18.3 (± 3.5) |

| AJCC IIA | 20 (± 1.0) | 70.0 (± 2.8) | 25.8 (± 2.9) | 14.1 (± 2.6) | 16 (± 2.0) | 58.4 (± 7.6) | 9.9 (± 6.3) | 5.0 (± 4.7) |

| AJCC IIB | 19 (± 0.4) | 68.2 (± 0.9) | 25.2 (± 0.9) | 15.3 (± 0.8) | 17 (± 0.9) | 66.1 (± 3.1) | 12.7 (± 2.6) | 4.5 (± 2.3) |

| AJCC III | 16 (± 0.4) | 59.4 (± 1.1) | 16.8 (± 0.9) | 7.9 (± 0.7) | 15 (± 2.7) | 53.3 (± 7.2) | 6.8 (± 4.3) | 0.0 |

| IA vs IB | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.014a | P = 0.158 | P = 0.014a | P = 0.035a |

| IB vs IIA | P = 0.000a | P = 0.010a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.001a | P = 0.014a | P = 0.030a | P =0.023a |

| IIA vs IIB | P = 0.958 | P = 0.541 | P = 0.843 | P = 0.659 | P = 0.425 | P = 0.348 | P = 0.681 | P = 0.924 |

| IIB vs III | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.018a | P = 0.102 | P = 0.240 | P = 0.050 |

| Prognostic comparison of different modified stages | ||||||||

| Modified IA | 38 (± 3.6) | 84.7 (± 1.7) | 51.7 (± 2.5) | 39.4 (± 2.7) | 32 (± 5.3) | 84.2 (± 4.0) | 45.4 (± 6.6) | 36.0 (± 7.1) |

| Modified IB | 27 (± 1.3) | 80.7 (± 1.2) | 40.1 (± 1.6) | 27.6 (± 1.6) | 24 (± 1.6) | 79.0 (± 2.9) | 28.6 (± 4.0) | 20.9 (± 4.0) |

| Modified IIA | 25 (± 1.4) | 75.6 (± 2.0) | 36.3 (± 2.3) | 22.5 (± 2.2) | 21 (± 3.3) | 77.3 (± 7.1) | 22.1 (± 7.6) | 14.7 (± 6.6) |

| Modified IIB | 20 (± 0.5) | 69.7 (± 1.0) | 25.4 (± 1.0) | 15.7 (± 0.9) | 18 (± 1.1) | 67.1 (± 3.4) | 10.5 (± 2.8) | 4.1 (± 2.2) |

| Modified III | 16 (± 0.3) | 60.0 (± 0.9) | 17.4 (± 0.8) | 8.6 (± 0.7) | 15 (± 1.0) | 56.2 (± 4.5) | 7.8 (± 2.8) | 0.0 (± 0.0) |

| IA vs IB | P = 0.000a | P = 0.055 | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.044a | P = 0.293 | P = 0.029a | P = 0.064 |

| IB vs IIA | P = 0.008a | P = 0.029a | P = 0.175 | P = 0.061 | P = 0.425 | P = 0.825 | P = 0.449 | P = 0.422 |

| IIA vs IIB | P = 0.000a | P = 0.008a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.004a | P = 0.043a | P = 0.195 | P = 0.152 | P = 0.128 |

| IIB vs III | P = 0.000a | P =0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.000a | P = 0.004a | P = 0.053 | P = 0.495 | P = 0.062 |

When patients from the West China Hospital database were used as test samples, the survival functions of patients with the 8th edition AJCC stage IA vs stage IB (P = 0.014, Table 5C and Figure 4C), stage IB vs stage IIA (P = 0.001), and stage IIB vs stage III (P = 0.018) were significantly different. However, the survival time and survival rate of patients with stage IIA were lower than those of patients with stage IIB, and there was no significant difference (MST 16 vs 17 mo, 1-year survival rate 58.4% vs 66.1%, 3-year survival rate 9.9% vs 12.7%, and 5-year survival rate 5.0 vs 4.5%, P > 0.05 for all). When a modified stage scheme was applied, the MSTs of patients with modified stage IA, IB, IIA, IIB and III were 32 mo, 24 mo, 21 mo, 18 mo, and 15 mo, respectively. There were significant differences in survival times between patients with modified stage IA vs patients with modified stage IB (P = 0.044), patients with modified stage IIA vs patients with modified stage IIB (P = 0.043), and patients with modified stage IIB vs patients with modified stage III (P = 0.004). There was no significant difference in survival time between patients with modified stage IB and those with modified stage IIA (P = 0.425) (Table 5D, Figure 4D).

The 8th edition of the AJCC pancreatic cancer staging system evaluates T stage (local invasion) in terms of tumor diameter and invasion of the SMA, CHA, or CA[2]. Compared with the 7th edition, the factor of extrapancreatic extension is excluded from the assessment of T stage. Since extrapancreatic extension generally involves invasion of the stomach, extrahepatic bile duct, duodenum, colon, CA, SMA, MPV, etc., the judgment and prognostic significance of extrapancreatic extension vary greatly from center to center[8-10].

The 8th edition of the AJCC TNM staging of pancreatic cancer eliminates the effect of MPV invasion, and tumors with MPV invasion are all classified as T3 tumors in the 7th edition AJCC staging system but are now restaged as T1, T2, and T3 diseases according to tumor size[2], although the prognostic impact of MPV invasion on pancreatic cancer remains controversial. Wang et al[11] retrospectively compared the PD with venous resection group (n = 62, pathological MPV invasion accounted for 76%) and the PD without venous resection group (n = 60) and found that the PD with venous resection group had a relatively poor prognosis (MST 18 vs 31 mo, P = 0.016) and that venous invasion rather than vein resection was predictive of survival. Rehders et al[12] compared 39 cases of pancreatic resection combined with vascular resection (35 cases of MPV resection and 4 cases of MPV + SMA resection) and 69 cases of pancreatic resection and concluded that vascular invasion was an indicator of tumor topography instead of tumor biology, but the patients in this study were followed for only 28 mo, with no long-term prognosis and no ratio of microscopic MPV involvement reported. Other studies compared the prognosis of the PD with venous resection group (n = 22, pathological MPV invasion accounted for 64%) with that of the PD group (n = 54) and suggested no difference between the prognoses of the two groups (P = 0.18)[13]. In these studies, the prognosis of the MPV resection group was affected by both MPV invasion and MPV resection. However, the probability of pathological MPV invasion varied between these studies and may have affected the prognosis. A case-control study showed that the median survival (42 mo vs 22 mo, n = 0.02) and overall 3-year survival rates (60% vs 31%, P = 0.03) were lower in patients with pathological MPV invasion compared with patients who also underwent PD combined with venous resection without pathological MPV invasion[4]. Mierke et al[5] compared the effects of MPV resection (P) and invasion (I) on survival [11.9 (P+I+) vs 16.1 (P+I-) vs 20.1 (P-I-) mo] in 179 cases of PD/TP (P = 0.01). The multivariate analysis showed that only pathological MPV invasion (P = 0.01) indicated a poor prognosis. A multicenter study conducted in Italy found that pathological MPV invasion (P = 0.0052) and adjuvant chemotherapy (P = 0.0041) were significantly associated with prognosis[6]. Okabayashi et al[14] found that the incidence of postoperative peritoneal dissemination and the accumulative rate of recurrence at 2 years after surgery in the MPV+ group were higher than those in the MPV- group. Therefore, it has been proven that combined MPV resection is a safe surgical technique[11-13]. In clinical practice, in all patients with MPV resection, a large proportion of pathological specimens exhibited no real tumor invasion of the MPV. This may bias the results reported in earlier studies. In our central database, 43.3% (n = 110) of patients who underwent combined MPV resection were confirmed to have true pathologic invasion. Pathological invasion of the MPV may be an important factor affecting patient prognosis.

To explore whether the 8th edition of the AJCC staging system provides a better prognostic assessment in the presence of MPV invasion, we stratified the population by whether there was microscopically confirmed MPV invasion and then compared the prognosis of patients in each stage. In the MPV- group, the survival functions of patients with stage IA vs patients with stage IB, patients with stage IB vs patients with stage IIA, and patients with stage IIB vs patients with stage III were significantly different, but the survival functions of patients with stage IIA and patients with stage IIB were not significantly different. In the MPV+ group of the SEER database, there was no significant difference between the survival functions of patients at different stages. There were statistically significant differences between the 3-year survival rates of patients with stage IIA vs patients with stage IIB and between the 1-year survival rates of patients with stage IIB vs patients with stage III, but there was no significant difference between the 1-, 3-, or 5-year survival rates of patients with stage IA-IB-IIA, suggesting that patients with stage IA-IB-IIA (T1-3N0) with MPV invasion have the same prognosis. Data from the West China Hospital database showed a similar result.

The statistical analysis results described above showed that the 8th edition of the AJCC staging system of pancreatic cancer could not accurately predict the prognosis of patients with MPV invasion. As a sign of local tumor extension, MPV invasion is correlated with T stage and is relatively independent of N stage. In the SEER database, there was a statistically significant difference in survival times between patients with T1N0, T2N0, and T3N0 stages without MPV invasion, while the T1N0, T2N0, and T3N0 subgroups in the MPV group had similar prognoses. Then, we merged T1-3N0 patients with MPV invasion into one group (MPV+T1-3N0) and compared their prognoses with those of the T1N0, T2N0, and T3N0 subgroups in the MPV- group. The results showed that the prognoses of patients with MPV+T1-3N0 and MPV-T3N0 were at the same level, indicating that once the tumors invade the MPV, the earlier T stage cannot provide a better prognosis for patients. We recommend that primary tumors with MPV invasion be classified into T3 diseases. Sgroi et al[15] retrospectively analyzed 147 pancreatic cancer patients who underwent PD/TP and concluded that the 1-year survival rate of vascular reconstruction in patients with T3 tumors (in which 49/60 underwent venous resection and reconstruction) was equivalent to that of patients without vascular resection.

Because there is no correlation between MPV invasion and N stage, most studies support that lymph node staging be divided into three N stages according to the number of positive lymph nodes (0, 1-3, and >4 lymph nodes), which has good clinical and statistical significance[10,16]. We followed the N staging of the eighth edition of the AJCC pancreatic cancer staging system.

A previous analysis found that patients with stage IIA and stage IIB have similar prognoses. Since stage IIB includes three subgroups, T1N1, T2N1, and T3N1, we compared the survival functions of patients with stage IIA with those of patients with stage T1N1, T2N1, and T3N1 to explore whether these three subgroups have the same prognosis as patients with stage IIA (T3N0). The survival analysis showed that the prognosis of patients with stage IIA was the same as that of patients in the T2N1 subgroup but different from that of patients in the T1N1 and T3N1 subgroups. Further comparison showed that the prognosis of patients in the T1N1 subgroup was worse than that of patients with stage IB of the AJCC staging system and better than that of patients with stage IIA. The prognosis of patients in the T3N1 subgroup was the same as that of patients with stage III (T1-3N2). According to this result, the modified stage of PDAC is defined in Table 4. Shi et al[17] analyzed the SEER database and the Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center database and combined T3N0M0 and T2N1M0 into one stage, but they did not consider the impact of MPV invasion on prognosis.

In the modified stage, the survival times of patients with T1, T2, and T3 were significantly different, and the standard error of the MST of patients with T3 was significantly reduced, indicating that intragroup variation could be reduced by restaging the patients with MPV invasion into T3. The prognosis of each modified stage was different, except that no significant difference was reached between the survival functions of patients with modified stage IB and patients with modified stage IIA in the West China Hospital database. This finding may be due to the small sample size of patients with modified stage IIA.

There are some limitations to this study. First, the MPV+ group of the SEER cohort could not be completely separated. The MPV+ group in the SEER database, or rather, group of patients whose variable CS extension labeled as 540, represented the patients with tumor invading GDA, hepatic artery, pancreaticoduodenal artery, MPV, or transverse colon but not invading the SMA, CA, aorta, or distant organs. The inclusion of possible patients in whom tumors involved the transverse colon, hepatic artery, or GDA without MPV invasion may have affected the results. However, in clinical practice, MPV invasion occurs more often than transverse colon, hepatic artery, and GDA infiltration. From the West China Hospital database, we included 689 patients with no postoperative pathology indicating transverse colon, hepatic artery, or GDA invasion. Second, this study excluded patients in whom the number of lymph nodes examined was 5 or less (n = 836 in the SEER database and n = 69 in the West China Hospital database) so that the population could be divided into three groups, with the number of positive lymph nodes classified as 0, 1-3, and 4 or more. According to the consensus reached at the ISGPS conference, the number of lymph nodes examined in pancreatic cancer surgical specimens should be 15 or more, but patients that met the requirement accounted for less than half (48.0%, n = 4022) in the SEER cohort and 40.9% (n = 310) in the West China Hospital cohort. Complete removal of these patients could make the results unable to represent the prognosis of pancreatic cancer patients in the real world. Next, the pathologic stage was assessed after the first surgical approach. While standard therapies for borderline resectable and unresectable pancreatic cancer include preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy, it is unknown whether patients with downstaged tumors after neoadjuvant chemotherapy display a similar survival function as those with resectable tumors at the same stage. Therefore, we included only patients with resectable diseases in the West China Hospital cohort. However, the SEER database provides no data about resectability or whether patients received neoadjuvant therapy. Moreover, data from this center were limited and may have had admission rate bias, which needs to be verified with multicenter data.

In summary, this study found that the 8th edition of the AJCC pancreatic cancer staging system still has two points that can be improved upon to predict prognosis: First, the prognosis of patients with MPV invasion cannot be accurately evaluated; second, the prognosis of patients with stage IIA and stage IIB is not different. We demonstrated that tumors with MPV invasion should be incorporated into T3 stage and developed an available modified staging system that outperformed the 8th edition of the AJCC staging system for pancreatic cancer.

The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) excludes extrapancreatic extension from the assessment of T stage and restages tumors with mesenterico-portal vein (MPV) invasion into T1-3 diseases according to tumor size.

In recent studies, MPV invasion is believed to be correlated with a poor prognosis. It would be useful for clinicians and researchers to study on whether the 8th edition of the AJCC staging system of PDAC could accurately predict the prognosis of patients with MPV invasion.

To study whether the inclusion of MPV invasion can further improve the 8th edition of the AJCC staging system for PDAC.

This study retrospectively included 8th edition AJCC T1-3N0-2M0 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy/total pancreatectomy from two databases: 7539 patients from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database and 689 patients from the West China Hospital database. Survival data were comprehensively analyzed.

This study showed that MPV invasion is an independent factor for predicting survival. The prognosis of patients with MPV invasion cannot be accurately evaluated according to the 8th edition of AJCC staging. The prognosis of patients with stage IIA and stage IIB was not different. A modified staging system which restages tumors with MPV invasion into T3 diseases outperformed the 8th edition of the AJCC staging system in predicting the prognosis of pancreatic cancer.

This study confirmed that MPV invasion is closely associated with the prognosis of PDAC patients. However, the 8th edition of the AJCC staging could not accurately predict the prognosis of patients with MPV invasion. We demonstrated that tumors with MPV invasion should be incorporated into T3 diseases and developed an available modified staging system that outperformed the 8th edition of the AJCC staging system in predicting the prognosis of PDAC patients.

The T stage of cancer is generally evaluated according to tumor diameter and local extension. Previous staging system evaluated the T stage of pancreatic cancer with extrapancreatic extension which is difficult to be determined, and is differently implemented in each center. With the publication of the 8th edition AJCC cancer staging manual, extrapancreatic extension was excluded from the assessment of T stage of pancreatic exocrine tumors, and the effect of local extension on the prognosis has been neglected (except for artery invasion). The newest data of the SEER database has no information about the extension. However, MPV invasion does have impact on the survival of PDAC patients. We were inspired by the comparison of the prognosis of patients with several different extrapancreatic tissue extensions. Not all the extrapancreatic extension but certain type of local extension should be valued.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Isaji S, Zhang XB S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11573] [Cited by in RCA: 13149] [Article Influence: 1878.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Kakar S, Pawlik TM, Allen PJ, Vauthey JN, Amin MB. Exocrine Pancreas. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. In: Amin MB, editor. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2016: 337-347. |

| 3. | PancreasHead – Schema Index. 2013 Sep 11 [cited 12 November 2019] In: American College of Surgeons web site [Internet]. Available from: http://web2.facs.org/cstage0205/pancreashead/PancreasHeadschema.html. |

| 4. | Turrini O, Ewald J, Barbier L, Mokart D, Blache JL, Delpero JR. Should the portal vein be routinely resected during pancreaticoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma? Ann Surg. 2013;257:726-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mierke F, Hempel S, Distler M, Aust DE, Saeger HD, Weitz J, Welsch T. Impact of Portal Vein Involvement from Pancreatic Cancer on Metastatic Pattern After Surgical Resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:730-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ramacciato G, Nigri G, Petrucciani N, Pinna AD, Ravaioli M, Jovine E, Minni F, Grazi GL, Chirletti P, Tisone G, Napoli N, Boggi U. Pancreatectomy with Mesenteric and Portal Vein Resection for Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: Multicenter Study of 406 Patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2028-2037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Willett CG, Lewandrowski K, Warshaw AL, Efird J, Compton CC. Resection margins in carcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Implications for radiation therapy. Ann Surg. 1993;217:144-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jamieson NB, Foulis AK, Oien KA, Dickson EJ, Imrie CW, Carter R, McKay CJ. Peripancreatic fat invasion is an independent predictor of poor outcome following pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:512-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Saka B, Balci S, Basturk O, Bagci P, Postlewait LM, Maithel S, Knight J, El-Rayes B, Kooby D, Sarmiento J, Muraki T, Oliva I, Bandyopadhyay S, Akkas G, Goodman M, Reid MD, Krasinskas A, Everett R, Adsay V. Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma is Spread to the Peripancreatic Soft Tissue in the Majority of Resected Cases, Rendering the AJCC T-Stage Protocol (7th Edition) Inapplicable and Insignificant: A Size-Based Staging System (pT1: ≤2, pT2: >2-≤4, pT3: >4 cm) is More Valid and Clinically Relevant. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2010-2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Allen PJ, Kuk D, Castillo CF, Basturk O, Wolfgang CL, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Ferrone CR, Morales-Oyarvide V, He J, Weiss MJ, Hruban RH, Gönen M, Klimstra DS, Mino-Kenudson M. Multi-institutional Validation Study of the American Joint Commission on Cancer (8th Edition) Changes for T and N Staging in Patients With Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2017;265:185-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang F, Gill AJ, Neale M, Puttaswamy V, Gananadha S, Pavlakis N, Clarke S, Hugh TJ, Samra JS. Adverse tumor biology associated with mesenterico-portal vein resection influences survival in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1937-1947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rehders A, Stoecklein NH, Güray A, Riediger R, Alexander A, Knoefel WT. Vascular invasion in pancreatic cancer: tumor biology or tumor topography? Surgery. 2012;152:S143-S151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Al-Haddad M, Martin JK, Nguyen J, Pungpapong S, Raimondo M, Woodward T, Kim G, Noh K, Wallace MB. Vascular resection and reconstruction for pancreatic malignancy: a single center survival study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1168-1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Okabayashi T, Shima Y, Iwata J, Morita S, Sumiyoshi T, Kozuki A, Saisaka Y, Tokumaru T, Iiyama T, Noda Y, Hata Y, Matsumoto M. Reconsideration about the aggressive surgery for resectable pancreatic cancer: a focus on real pathological portosplenomesenteric venous invasion. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2015;400:487-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sgroi MD, Narayan RR, Lane JS, Demirjian A, Kabutey NK, Fujitani RM, Imagawa DK. Vascular reconstruction plays an important role in the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:475-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Strobel O, Hinz U, Gluth A, Hank T, Hackert T, Bergmann F, Werner J, Büchler MW. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: number of positive nodes allows to distinguish several N categories. Ann Surg. 2015;261:961-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shi S, Hua J, Liang C, Meng Q, Liang D, Xu J, Ni Q, Yu X. Proposed Modification of the 8th Edition of the AJCC Staging System for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2019;269:944-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |