Published online Jan 21, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i3.300

Peer-review started: October 5, 2018

First decision: November 7, 2018

Revised: November 30, 2018

Accepted: December 13, 2018

Article in press: December 13, 2018

Published online: January 21, 2019

Processing time: 110 Days and 11.7 Hours

Endoscopic polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) are the established treatment standards for colorectal polyps. Current research aims at the reduction of both complication and recurrence rates as well as on shortening procedure times. Cold snare resection is the emerging standard for the treatment of smaller (< 5mm) polyps and is possibly also suitable for the removal of non-cancerous polyps up to 9 mm. The method avoids thermal damage, has reduced procedure times and probably also a lower risk for delayed bleeding. On the other end of the treatment spectrum, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) offers en bloc resection of larger flat or sessile lesions. The technique has obvious advantages in the treatment of high-grade dysplasia and early cancer. Due to its minimal recurrence rate, it may also be an alternative to fractionated EMR of larger flat or sessile lesions. However, ESD is technically demanding and burdened by longer procedure times and higher costs. It should therefore be restricted to lesions suspicious for high-grade dysplasia or early invasive cancer. The latest addition to endoscopic resection techniques is endoscopic full-thickness resection with specifically developed devices for flexible endoscopy. This method is very useful for the treatment of smaller difficult-to-resect lesions, e.g., recurrence with scar formation after previous endoscopic resections.

Core tip: Endoscopic polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection are the standard treatment options for colorectal neoplasia. Current research is evaluating cold snare resection for the treatment of smaller non-cancerous polyps, aiming to reduce procedure times and complication rates. Endoscopic submucosal dissection has great potential for the en bloc resection of larger flat or sessile lesions. However, it is technically demanding and time consuming and should be reserved for histologically advanced lesions. Endoscopic full-thickness resection is a welcome addition to the armamentarium of endoscopic resection techniques and is very useful for the treatment of smaller difficult-to-resect lesions.

- Citation: Dumoulin FL, Hildenbrand R. Endoscopic resection techniques for colorectal neoplasia: Current developments. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(3): 300-307

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i3/300.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i3.300

Colorectal cancer screening and endoscopic polyp resection can reduce mortality from colorectal cancer[1] and are now recommended by many national guidelines[2]. Snare polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) are the established treatment standards for polyp removal[3-6]. The advantages of these methods are relatively short procedure times and an accepted complication rate, with delayed bleeding in 0.9% and a risk of perforation between 0.4% and 1.3% depending on the size and location of the resected lesion[5]. A recent modification is underwater EMR. A limited number of studies suggest that larger lesions can be removed en bloc with low complication rates and short procedure times[7]. However, despite being widely practiced, the standard EMR techniques are not perfect. Thus, there still is a considerable rate of adverse events, particularly perforation and bleeding. Moreover, larger lesions cannot reliably be removed, which results in incomplete resections. Finally, dense fibrosis results in nonlifting, difficult-to-treat lesions. This minireview will focus on current advances in endoscopic resection techniques attempting to overcome these problems, particularly cold snare resection to reduce complication rates, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) to increase the en bloc resection rate for larger flat or sessile lesions, and endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) for difficult-to-resect (nonlifting) lesions.

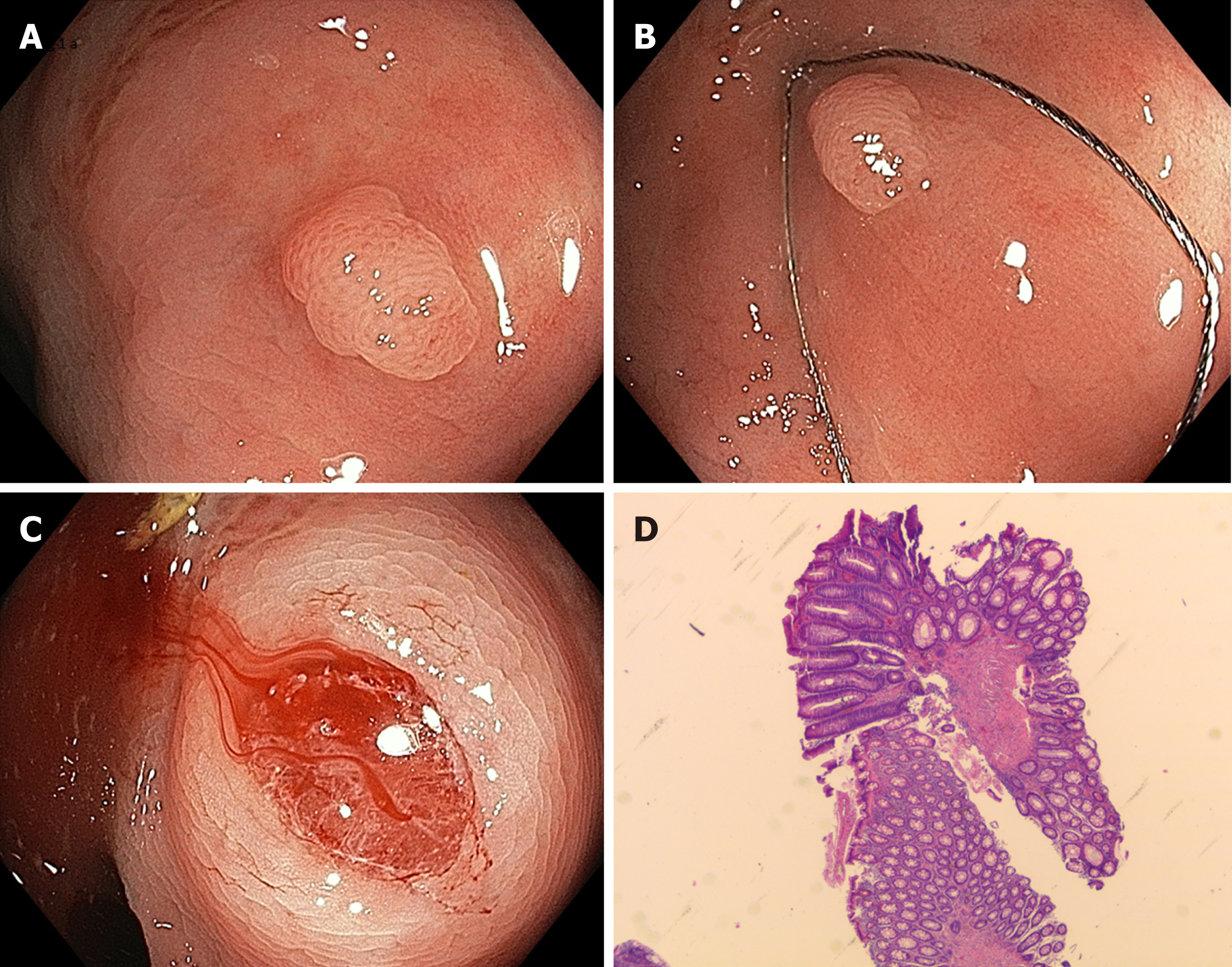

The disadvantages of conventional hot snare resection are caused by thermal injury. Possible complications are delayed bleeding and thermal injury resulting in postpolypectomy syndrome and delayed perforation. Recently, cold snare resection has been introduced as a possible alternative. The method involves snaring - mostly with dedicated devices - without the use of additional electrocautery (Figure 1). It has mainly been applied to small (up to 5 mm) polyps but has recently been extended to larger lesions. This method offers possible advantages of reducing procedure time and postinterventional complications while maintaining the same efficacy as conventional hot snare resection.

Several studies have been published on this subject. A recent meta-analysis included eight randomized controlled studies with 3195 interventions[8]. Compared to conventional techniques, cold snare resection showed similar efficacy but significantly shortened procedure times and a trend towards reduced rates of delayed bleeding. On the other hand, possible disadvantages of cold snare resection techniques were highlighted in a histopathology study on 184 polyps[9]. In this study, cold snare resection was associated with increased rates of specimen damage, increased rates of positive margins and a decreased resection depth. Incomplete resections were observed predominantly for serrated/hyperplastic lesions[9]. Therefore, cold snare resection does not seem to be suitable for malignant lesions where one-piece EMR or ESD are recommended[6]. In addition, cold snare resection has also been applied to slightly larger lesions. Along these lines, piecemeal cold snare resection was reported for 94 lesions > 10 mm with no adverse events and a short-term recurrence rate of 9.7%[10]. A similar series of 41 lesions with a median size of 15 mm showed no evidence of complications or recurrence after a follow-up period of 6 mo[11]. The current European guideline recommends cold snare resection as the preferred technique for removal of diminutive polyps (size ≤ 5 mm). In addition, the guideline recommends this technique also for sessile polyps of 6-9 mm size, although formal evidence comparing efficacy with conventional hot snare polypectomy is still lacking[6]. With regard to technical issues, the use of dedicated snares seems to be beneficial[12].

In summary, cold snare resection is becoming the standard of treatment for diminutive (up to 5 mm) and also to small sessile non-cancerous polyps (up to 9 mm). Larger studies will need to define the exact role of cold snare resection in polyp removal.

The major advantages of EMR are the relatively short procedure times (ca. 35 min for larger lesions[13]) and an acceptable complication rate, with delayed bleeding in 0.9%[5] and a perforation rate between 0.4% and 1.3%[5,14]. It should be emphasized that the complication rates depend on the size and location of the resected lesion. Thus, a delayed bleeding rate of 6.7% was reported in a recent multicenter study including > 2000 EMRs[15]. Risk factors for bleeding included the size lesion, polyp location in the right colon and patient comorbidity[15]. The frequency of perforation after EMR is between 0.4% and 1.3% and depends on the size and location of the resected lesion[5,14].

The disadvantage of EMR is its size limitation of approximately 20 mm. Larger lesions cannot be resected en bloc and instead must be removed in fragments (piecemeal EMR technique). This fragmentation implies that a complete resection cannot be confirmed by histopathology and piecemeal EMR is associated with recurrence rates of approximately 15%-20% in retrospective series[16,17] and more than 30% in a recent prospective study on endoscopic piecemeal resection of 252 adenomas > 20 mm in size[18]. Many risk factors for recurrences have been identified, including lesion size, number of resected fragments, and more advanced histology (tubulovillous adenoma or high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia)[17,19]. Moreover, multiple recurrences are not a rare event (ca. 20%-40%), although most of them are amenable to further endoscopic treatment[14]. Notably, incomplete endoscopic resection of adenomas is thought to be responsible for 20%-25% of interval cancers[20]. The recurrence rate implies the necessity of endoscopic controls and compliance with follow-up endoscopy[16,17].

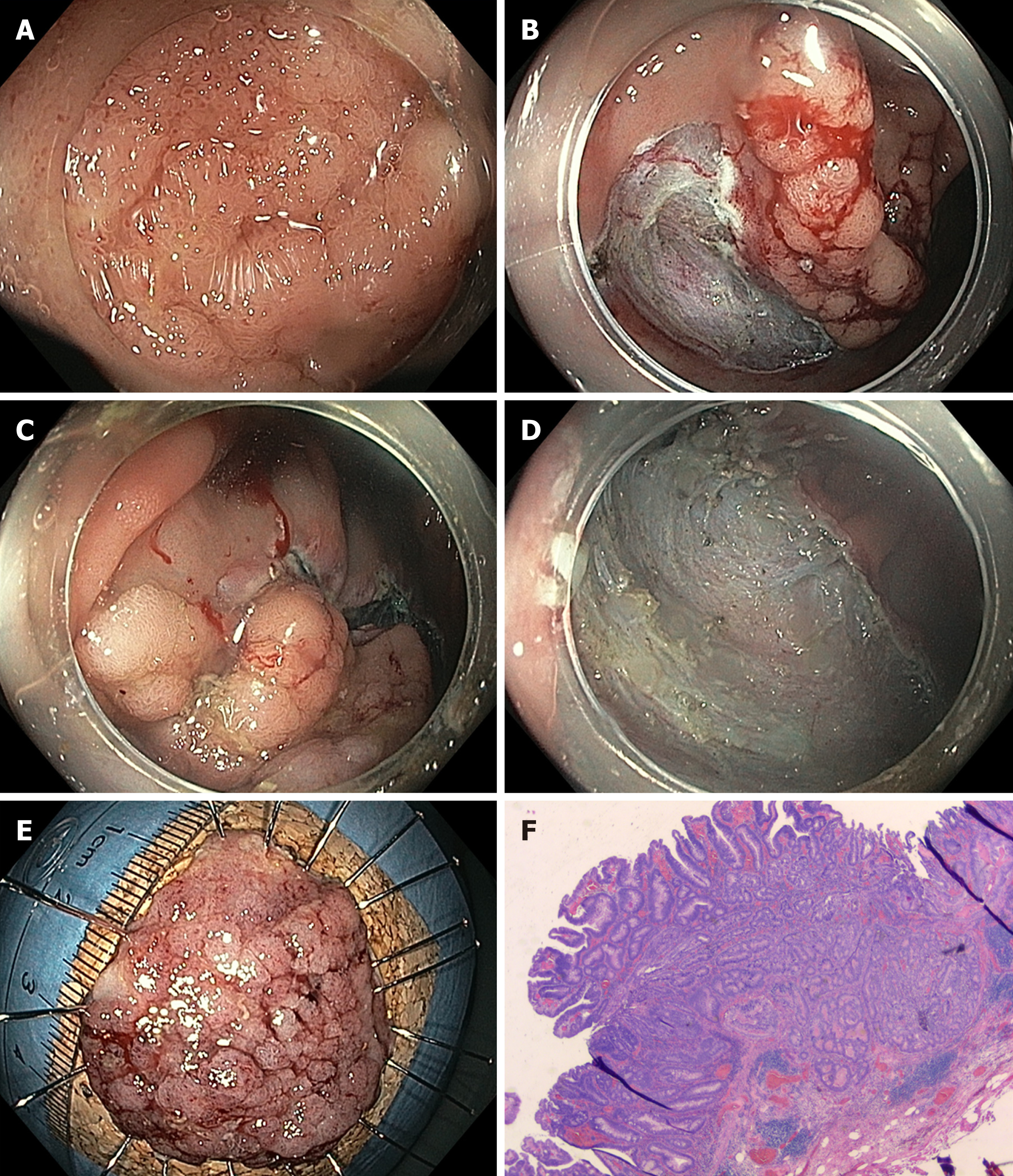

Whereas EMR of larger flat or sessile lesions will result in fragmented resection, ESD - developed in Japan for the treatment of early gastric cancer - offers the possibility of en bloc resection for larger lesions. The method consists of incision of the mucosa followed by submucosal dissection underneath the lesion to yield an en bloc specimen with no size restriction (Figure 2). ESD is much more technically demanding than EMR and requires longer procedure times, with a median procedure time of ca. 70 min in a recent meta-analysis[21,22]. The procedure time and level of complexity depend primarily on endoscopic access to the lesion and access to the submucosal compartment[23]. The method is not considered standard in Europe[6], but it has been included in the Japanese guidelines as the standard technique for larger neoplastic lesions for which en bloc resection is desirable[4]. Most clinical data on colorectal ESD are from Asia. Larger (> 500 patients) retrospective or prospective observational studies report en bloc and R0 resection rates of 84% to 94.5%, with very few recurrences[4,24]. In contrast, experience with colorectal ESD is very limited in the Western world. This is mainly due to the lack of training opportunities, the high level of skills necessary to perform colorectal ESD and the fact that this method has longer procedure times and probably also higher complication rates than piecemeal EMR. However, it is possible to achieve competence in colorectal ESD without prior expertise in gastric ESD, particularly if training is performed under the supervision of (Eastern) ESD experts[25-27]. Consequently, data from Western endoscopists are rare, with smaller case series and only two publications on larger (n > 150) series, mainly including lesions localized in the rectum[28,29]. Both en bloc and R0 resection rates are lower in those publications than in studies from Asian populations, which is particularly true for larger lesions in the proximal colon[28]. Adverse events are more common for ESD than for EMR, with published perforation rates of approximately 4.8% (2%-14%) for the former[4,30,31]. However, most perforations are minor and can be closed with standard clips during or at the end of the procedure, and the rate of emergency surgery is relatively low (ca. 0.5%). Delayed bleeding is observed after 1.5%-2.8% of interventions. Strictures are observed only occasionally, e.g., after circumferential resections in the rectum[30].

A recent meta-analysis highlighted the differences between EMR and ESD[22], with the latter having higher en bloc resection rates that come at the cost of higher complication rates (although most complications can be treated conservatively) and longer procedure times. Finally, while the concept of en bloc resection of neoplasia is appealing, ESD also has higher costs than EMR. A recent cost-effectiveness analysis of wide-field EMR vs ESD concluded that selective ESD for high-risk lesions is the most cost-effective application of colorectal ESD[32]. Compared with laparoscopic surgery, ESD has major advantages, although a formal head-to-head comparison is still lacking[33-36].

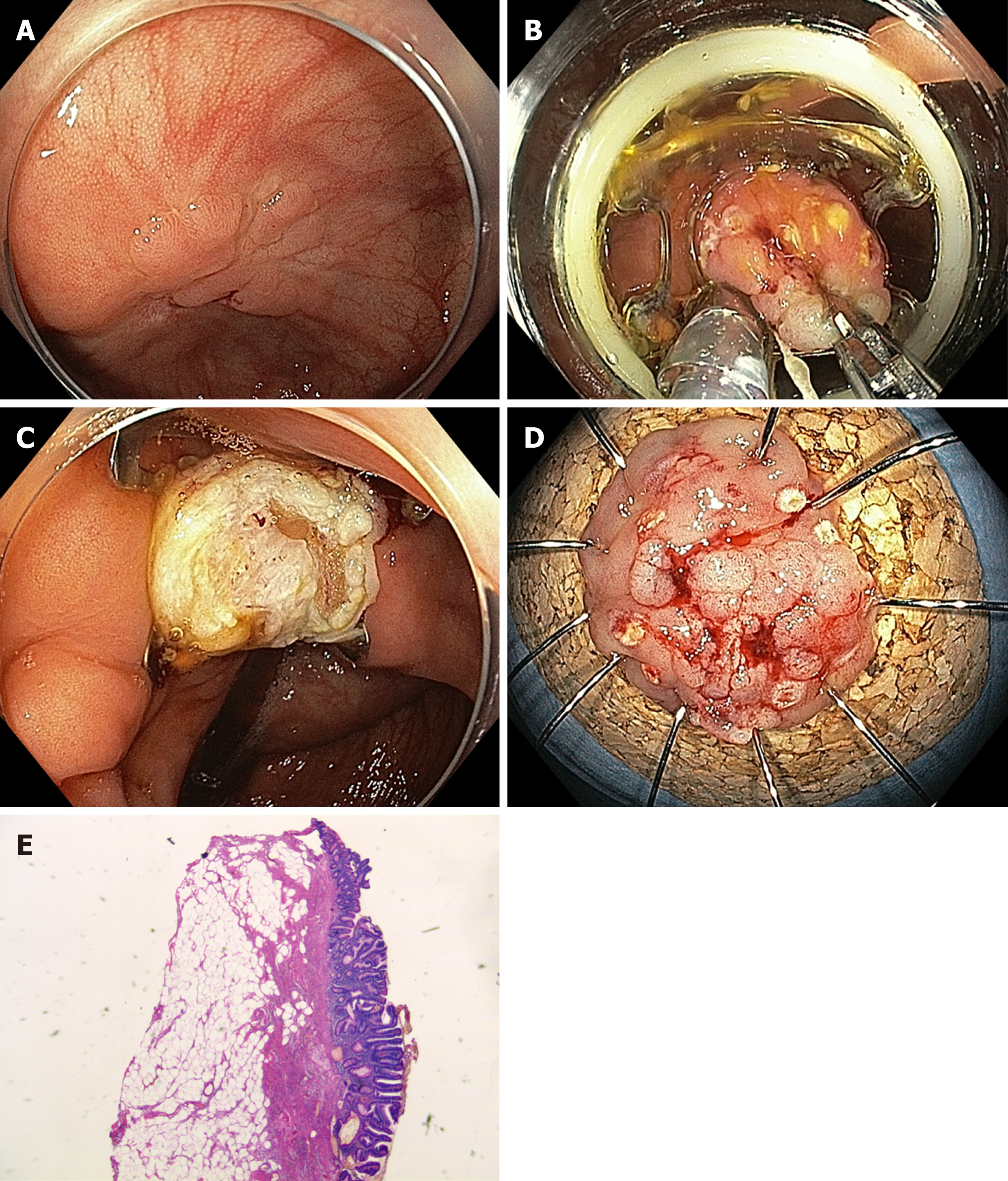

Conventional endoscopic resection may not be technically feasible in cases of severe fibrosis, e.g., due to scar formation in adenoma recurrences after previous resection or in cases of adenomas in specific anatomical locations, e.g., close to a diverticulum or at the appendiceal orifice. In these situations, EFTR may be a useful alternative. This method involves a full-thickness plication of the bowel wall, which is secured by an over-the-scope clip followed by resection of the bowel wall above the clip. The full thickness resection device (FTRD®) System (Ovesco, Tübingen, Germany) is a single-step full-thickness resection device combining a modified over-the-scope clip with an integrated snare[37]. After the lesion is marked, the colonoscope is retracted, and the FTRD is mounted and advanced to the target. The lesion is then pulled into the resection cap, and after deployment of the clip, the snare is closed and the tissue is cut (Figure 3). Alternatively, a flat over-the-scope clip (Padlock clip, US Endoscopy, Mentor, Ohio, United States) is used to create a plication, and the tissue above is then resected with a snare.

EFTR is particularly useful for the resection of smaller (up to 15-20 mm) nonlifting lesions. To date, there are only limited data on the efficacy of the method, usually performed with the FTRD device[38-41]. Procedure time depends mainly on the location of the lesion (sometimes passage to proximal locations can be difficult or even impossible). It is more time consuming than EMR, and the size of the lesions is limited by the size of the cap. In the largest prospective study published so far, the R0 resection rate was 77.7% for 127 patients with nonlifting adenomas. The overall complication rate was 9.9% and included perforation, fistula, bleeding and appendicitis; the rate of emergency surgery was 2.2%[42].

Polypectomy and EMR remain the standard treatment options for the removal of most colorectal neoplasia. They are relatively easy and quick to perform in terms of technique and have an acceptable complication rate. New developments are underway with cold snare resection as a method that might be associated with even shorter procedure times and lower complication rates. In addition, ESD has the potential for the en bloc resection of larger lesions; it should probably be reserved for larger lesions suspicious of high grade dysplasia or early invasive cancer. Finally, smaller difficult-to-resect lesions can now be treated effectively by EFTR.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Komeda Y, Yoshii S S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O'Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, Shi W, Bond JH, Schapiro M, Panish JF, Stewart ET, Waye JD. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1952] [Cited by in RCA: 2278] [Article Influence: 175.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Bénard F, Barkun AN, Martel M, von Renteln D. Systematic review of colorectal cancer screening guidelines for average-risk adults: Summarizing the current global recommendations. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:124-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 3. | Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM; American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 981] [Cited by in RCA: 1059] [Article Influence: 66.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tanaka S, Kashida H, Saito Y, Yahagi N, Yamano H, Saito S, Hisabe T, Yao T, Watanabe M, Yoshida M, Kudo SE, Tsuruta O, Sugihara K, Watanabe T, Saitoh Y, Igarashi M, Toyonaga T, Ajioka Y, Ichinose M, Matsui T, Sugita A, Sugano K, Fujimoto K, Tajiri H. JGES guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:417-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 434] [Article Influence: 43.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schmiegel W, Buchberger B, Follmann M, Graeven U, Heinemann V, Langer T, Nothacker M, Porschen R, Rödel C, Rösch T, Schmitt W, Wesselmann S, Pox C. S3-Leitlinie – Kolorektales Karzinom. Z Gastroenterol. 2017;55:1344-1498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ferlitsch M, Moss A, Hassan C, Bhandari P, Dumonceau JM, Paspatis G, Jover R, Langner C, Bronzwaer M, Nalankilli K, Fockens P, Hazzan R, Gralnek IM, Gschwantler M, Waldmann E, Jeschek P, Penz D, Heresbach D, Moons L, Lemmers A, Paraskeva K, Pohl J, Ponchon T, Regula J, Repici A, Rutter MD, Burgess NG, Bourke MJ. Colorectal polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2017;49:270-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 764] [Article Influence: 95.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gaglia A, Sarkar S. Evaluation and long-term outcomes of the different modalities used in colonic endoscopic mucosal resection. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30:145-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shinozaki S, Kobayashi Y, Hayashi Y, Sakamoto H, Lefor AK, Yamamoto H. Efficacy and safety of cold versus hot snare polypectomy for resecting small colorectal polyps: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:592-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ito A, Suga T, Ota H, Tateiwa N, Matsumoto A, Tanaka E. Resection depth and layer of cold snare polypectomy versus endoscopic mucosal resection. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1171-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Piraka C, Saeed A, Waljee AK, Pillai A, Stidham R, Elmunzer BJ. Cold snare polypectomy for non-pedunculated colon polyps greater than 1 cm. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E184-E189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tate DJ, Awadie H, Bahin FF, Desomer L, Lee R, Heitman SJ, Goodrick K, Bourke MJ. Wide-field piecemeal cold snare polypectomy of large sessile serrated polyps without a submucosal injection is safe. Endoscopy. 2018;50:248-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jung YS, Park CH, Nam E, Eun CS, Park DI, Han DS. Comparative efficacy of cold polypectomy techniques for diminutive colorectal polyps: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:1149-1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moss A, Williams SJ, Hourigan LF, Brown G, Tam W, Singh R, Zanati S, Burgess NG, Sonson R, Byth K, Bourke MJ. Long-term adenoma recurrence following wide-field endoscopic mucosal resection (WF-EMR) for advanced colonic mucosal neoplasia is infrequent: results and risk factors in 1000 cases from the Australian Colonic EMR (ACE) study. Gut. 2015;64:57-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Holmes I, Friedland S. Endoscopic Mucosal Resection versus Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Large Polyps: A Western Colonoscopist's View. Clin Endosc. 2016;49:454-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bahin FF, Rasouli KN, Byth K, Hourigan LF, Singh R, Brown GJ, Zanati SA, Moss A, Raftopoulos S, Williams SJ, Bourke MJ. Prediction of Clinically Significant Bleeding Following Wide-Field Endoscopic Resection of Large Sessile and Laterally Spreading Colorectal Lesions: A Clinical Risk Score. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1115-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Belderbos TD, Leenders M, Moons LM, Siersema PD. Local recurrence after endoscopic mucosal resection of nonpedunculated colorectal lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2014;46:388-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Briedigkeit A, Sultanie O, Sido B, Dumoulin FL. Endoscopic mucosal resection of colorectal adenomas > 20 mm: Risk factors for recurrence. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8:276-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Knabe M, Pohl J, Gerges C, Ell C, Neuhaus H, Schumacher B. Standardized long-term follow-up after endoscopic resection of large, nonpedunculated colorectal lesions: a prospective two-center study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:183-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tate DJ, Desomer L, Klein A, Brown G, Hourigan LF, Lee EY, Moss A, Ormonde D, Raftopoulos S, Singh R, Williams SJ, Zanati S, Byth K, Bourke MJ. Adenoma recurrence after piecemeal colonic EMR is predictable: the Sydney EMR recurrence tool. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:647-656.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Robertson DJ, Lieberman DA, Winawer SJ, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, Schatzkin A, Cross AJ, Zauber AG, Church TR, Lance P, Greenberg ER, Martínez ME. Colorectal cancers soon after colonoscopy: a pooled multicohort analysis. Gut. 2014;63:949-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang J, Zhang XH, Ge J, Yang CM, Liu JY, Zhao SL. Endoscopic submucosal dissection vs endoscopic mucosal resection for colorectal tumors: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8282-8287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Arezzo A, Passera R, Marchese N, Galloro G, Manta R, Cirocchi R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of endoscopic submucosal dissection vs endoscopic mucosal resection for colorectal lesions. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:18-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Takeuchi Y, Iishi H, Tanaka S, Saito Y, Ikematsu H, Kudo SE, Sano Y, Hisabe T, Yahagi N, Saitoh Y, Igarashi M, Kobayashi K, Yamano H, Shimizu S, Tsuruta O, Inoue Y, Watanabe T, Nakamura H, Fujii T, Uedo N, Shimokawa T, Ishikawa H, Sugihara K. Factors associated with technical difficulties and adverse events of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: retrospective exploratory factor analysis of a multicenter prospective cohort. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1275-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nishizawa T, Yahagi N. Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection: technique and new directions. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2017;33:315-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Uraoka T, Parra-Blanco A, Yahagi N. Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: is it suitable in western countries? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:406-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yang DH, Jeong GH, Song Y, Park SH, Park SK, Kim JW, Jung KW, Kim KJ, Ye BD, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Kim JH, Park YS, Byeon JS. The Feasibility of Performing Colorectal Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Without Previous Experience in Performing Gastric Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:3431-3441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Berr F, Wagner A, Kiesslich T, Friesenbichler P, Neureiter D. Untutored learning curve to establish endoscopic submucosal dissection on competence level. Digestion. 2014;89:184-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sauer M, Hildenbrand R, Oyama T, Sido B, Yahagi N, Dumoulin FL. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for flat or sessile colorectal neoplasia > 20 mm: A European single-center series of 182 cases. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E895-E900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Probst A, Ebigbo A, Märkl B, Schaller T, Anthuber M, Fleischmann C, Messmann H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early rectal neoplasia: experience from a European center. Endoscopy. 2017;49:222-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | ASGE Technology Committee. Maple JT, Abu Dayyeh BK, Chauhan SS, Hwang JH, Komanduri S, Manfredi M, Konda V, Murad FM, Siddiqui UD, Banerjee S. Endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1311-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bhatt A, Abe S, Kumaravel A, Vargo J, Saito Y. Indications and Techniques for Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:784-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Bahin FF, Heitman SJ, Rasouli KN, Mahajan H, McLeod D, Lee EYT, Williams SJ, Bourke MJ. Wide-field endoscopic mucosal resection versus endoscopic submucosal dissection for laterally spreading colorectal lesions: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Gut. 2018;67:1965-1973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kiriyama S, Saito Y, Yamamoto S, Soetikno R, Matsuda T, Nakajima T, Kuwano H. Comparison of endoscopic submucosal dissection with laparoscopic-assisted colorectal surgery for early-stage colorectal cancer: a retrospective analysis. Endoscopy. 2012;44:1024-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ahlenstiel G, Hourigan LF, Brown G, Zanati S, Williams SJ, Singh R, Moss A, Sonson R, Bourke MJ; Australian Colonic Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (ACE) Study Group. Actual endoscopic versus predicted surgical mortality for treatment of advanced mucosal neoplasia of the colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:668-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Nakamura F, Saito Y, Sakamoto T, Otake Y, Nakajima T, Yamamoto S, Murakami Y, Ishikawa H, Matsuda T. Potential perioperative advantage of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection versus laparoscopy-assisted colectomy. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:596-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Jayanna M, Burgess NG, Singh R, Hourigan LF, Brown GJ, Zanati SA, Moss A, Lim J, Sonson R, Williams SJ, Bourke MJ. Cost Analysis of Endoscopic Mucosal Resection vs Surgery for Large Laterally Spreading Colorectal Lesions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:271-278.e1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 37. | Schurr MO, Baur FE, Krautwald M, Fehlker M, Wehrmann M, Gottwald T, Prosst RL. Endoscopic full-thickness resection and clip defect closure in the colon with the new FTRD system: experimental study. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2434-2441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Fähndrich M, Sandmann M. Endoscopic full-thickness resection for gastrointestinal lesions using the over-the-scope clip system: a case series. Endoscopy. 2015;47:76-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Richter-Schrag HJ, Walker C, Thimme R, Fischer A. [Full thickness resection device (FTRD). Experience and outcome for benign neoplasms of the rectum and colon]. Chirurg. 2016;87:316-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Backes Y, Kappelle WFW, Berk L, Koch AD, Groen JN, de Vos Tot Nederveen Cappel WH, Schwartz MP, Kerkhof M, Siersema PD, Schröder R, Tan TG, Lacle MM, Vleggaar FP, Moons LMG; T1 CRC Working Group. Colorectal endoscopic full-thickness resection using a novel, flat-base over-the-scope clip: a prospective study. Endoscopy. 2017;49:1092-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Al-Bawardy B, Rajan E, Wong Kee Song LM. Over-the-scope clip-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection of epithelial and subepithelial GI lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:1087-1092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Schmidt A, Beyna T, Schumacher B, Meining A, Richter-Schrag HJ, Messmann H, Neuhaus H, Albers D, Birk M, Thimme R, Probst A, Faehndrich M, Frieling T, Goetz M, Riecken B, Caca K. Colonoscopic full-thickness resection using an over-the-scope device: a prospective multicentre study in various indications. Gut. 2018;67:1280-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |