Published online Oct 7, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i37.6902

Peer-review started: June 16, 2017

First decision: July 13, 2017

Revised: August 4, 2017

Accepted: August 15, 2017

Article in press: August 15, 2017

Published online: October 7, 2017

Processing time: 105 Days and 9.3 Hours

Achalasia is a rare esophageal motility disorder that is characterized by a loss of peristalsis in the distal esophagus and failure of lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. The risk of developing esophageal motility disorders, including achalasia, following bariatric surgery is controversial and differs based on the type of surgery. Most of the reported cases occurred with laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. To our knowledge, there are only three reported cases of achalasia after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and no reported cases after revision of the surgery. We present a case of a 70-year-old female who had a previous history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with revision. She presented with persistent nausea and regurgitation for one month. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed a dilated esophagus without strictures or stenosis. A barium study was performed after the endoscopy and was suggestive of achalasia. Those findings were confirmed by a manometry. The patient was referred for laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy.

Core tip: Achalasia is a rare esophageal motility disorder. It is uncommonly reported after bariatric surgeries. Achalasia is a very rare complication after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. We report a case of a 70-year-old female who she presented with persistent nausea and regurgitation for one month. She had a previous history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with revision. As part of her inpatient evaluation, a computed tomography of the chest, a barium study and an upper endoscopy were suggestive of achalasia. Those findings were confirmed by a manometry. The patient was referred for laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy.

- Citation: Abu Ghanimeh M, Qasrawi A, Abughanimeh O, Albadarin S, Clarkston W. Achalasia after bariatric Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery reversal. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(37): 6902-6906

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i37/6902.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i37.6902

Achalasia is a rare esophageal motility disorder characterized by loss of peristalsis in the distal esophagus and failure of lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation[1,2]. It usually presents with dysphagia for solids and liquids as well as regurgitation[3]. Primary achalasia is an idiopathic disease with unknown etiology, whereas secondary achalasia or pseudoachalasia is associated with infections, paraneoplastic syndromes and extrinsic compression by benign or malignant processes[4-6]. Interestingly, relationships have previously been reported between abnormalities in esophageal manometry, including achalasia, and both morbid obesity and bariatric surgery[7-18]. Most of the reported cases of achalasia after bariatric surgery occurred after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB)[11-14]. Achalasia after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is rare[15-18] and could be related to surgical trauma in the area[15]. In these cases, it is important to rule out stenosis of the gastrojejunostomy.

A 70-year-old female with a past medical history of coronary artery disease and morbid obesity (previous body mass index (BMI) of 52 kg/m2) presented to our institution with persistent nausea and regurgitation for one month.

Her surgical history was significant for laparoscopic cholecystectomy and laparoscopic RYGB approximately two years prior to presentation. Her post-operative course was complicated by a gastro-gastric fistula and gastro-jejunal anastomosis ulcer with gastrointestinal bleeding requiring admission to the hospital, blood transfusion and endoscopic hemostasis. Her surgery was revised approximately 2 mo prior to her presentation.

Her symptoms were mostly post-prandial. She also described mild dysphasia to both solids and liquids, so she started to drink in small sips. She denied any change in her weight or appetite, abdominal pain or change in bowel habits. Her vital signs were unremarkable. Her abdomen was soft, without tenderness to palpation and with bowel sounds present. The wound from her recent surgery was clean, with no evidence of discharge or poor healing.

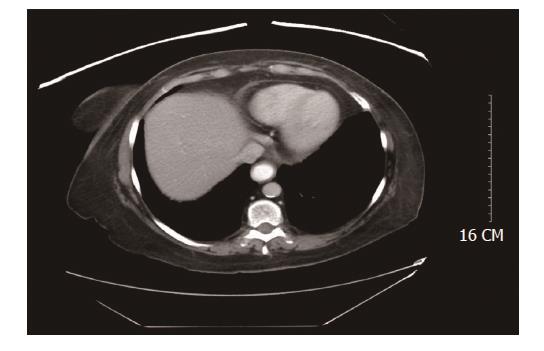

Initial laboratory workup showed alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 33 unit/L (normal 13-69 unit/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 35 unit/L (normal 15-46 unit/L) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 123 unit/L (normal 42-140 unit/L). A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast (Figure 1) showed enteric contrast within the dilated distal esophagus and was suspicious for a mild stricture at gastroesophageal sphincter (GES). There was no evidence of peri-gastric inflammatory changes. Her stool workup was negative for Clostridium difficile toxin, ova and parasites. She was started on IV hydration, given IV ondansetron 4 mg every 6 h as needed for nausea and admitted for further evaluation.

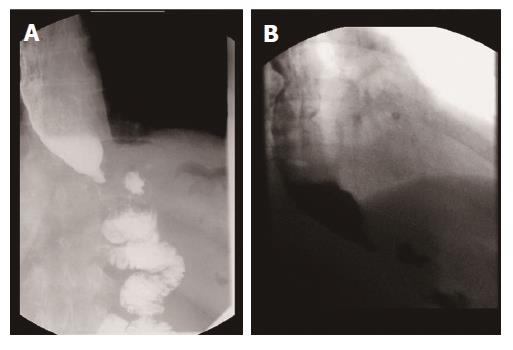

The next day, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed large amounts of thick secretions in the esophagus. The esophagus was tortuous, dilated and had a "sigmoid esophagus" appearance, but no strictures, stenosis or evidence of malignancy were noted. A Barium study (Figure 2) was performed after the EGD and showed persistent narrowing of the gastroesophageal junction with a moderately dilated, debris-filled esophagus proximally and some tertiary esophageal contractions. These findings were suggestive of achalasia.

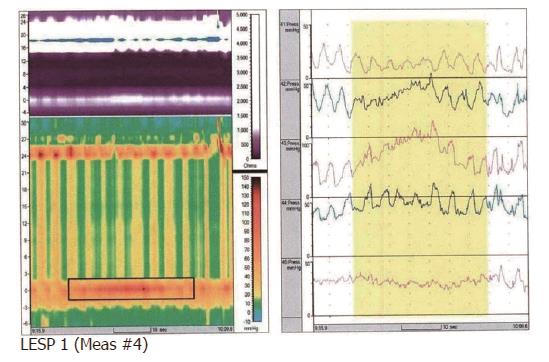

The patient was discharged with outpatient follow-up with a manometry study. The manometry was performed 2 wk later and revealed high pressure in the LES with abnormal relaxation and high resting pressure, in addition to aperistalsis. These results were consistent with type II achalasia (Figure 3). She was referred to surgery for evaluation and laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy.

Achalasia is a rare esophageal motility disorder that is characterized by neurodegeneration, preferentially involving the inhibitory nitric oxide-producing neurons. It leads to a loss of peristalsis in the distal esophagus and failure of LES relaxation[1,2]. It is derived from the Greek term meaning “does not relax”. Achalasia occurs equally in males and females, with an annual incidence of approximately 1.6 cases per 100000 individuals[2].

Dysphagia for solids and liquids and regurgitation of undigested food or saliva are the most common symptoms in patients with achalasia[3]. The etiology of primary achalasia is unknown, though autoimmune and viral infectious etiologies have been proposed[4,5]. In its secondary form or pseudoachalasia, there are many potential causes of esophageal motor abnormalities that are similar or identical to those of primary achalasia. Examples include infections such as Chagas disease, paraneoplastic syndromes and extrinsic compression of gastroesophageal junction by either benign or malignant processes[6].

Bariatric surgeries are among the fastest growing operative procedures worldwide[19-21]. They are recommended for adults who have a BMI of at least 40 kg/m2 or 35 kg/m2 with other comorbidities[21]. RYGP remains the most commonly performed bariatric procedure in the United States[19-21]. The risk of developing esophageal motility disorders, including achalasia, following bariatric surgery is still controversial and differs with the type of surgery[11-14,16-18]. Pseudoachalasia after LAGB placement has been described, though there is evidence that the pseudoachalasia may be reversible after the band is removed[11-14]. It has been postulated that malpositioning of the band near the gastroesophageal junction creates a high-pressure area, causing clinical symptoms of pseudoachalasia[11-14].

In contrast, the development esophageal motility disorders after RYGB is rare and has only been reported a few times in the literature (Table 1)[15-18]. To the best of our knowledge, there are only 3 reported cases of achalasia after RYGB[16-18], and this is the first case described after revision of RYGB. Interestingly, several case reports have been published on the simultaneous treatment of achalasia and morbid obesity with laparoscopic esophageal myotomy and gastric bypass[22-23]. The exact pathophysiology of motility disorders that develop after RYGB in general, and achalasia specifically, is unknown. Surgical trauma is one potential explanation. Shah et al[15] described a retrospective study of 64 patients with achalasia compared with a control group of 73 patients without achalasia evaluated by manometry and endoscopy. A significant association was found between achalasia and trauma to the upper gastrointestinal tract. Of the patients with operative trauma and achalasia, 2 had undergone gastric bypass. Finally, it is worth mentioning that another important consideration in similar cases is to rule out stenosis of the gastrojejunostomy, which we did in our patient.

| Case | Age and gender | Pre-operative BMI (kg/m2) | Procedure | Presentation | Onset of symptoms postoperative | Upper GI series/Barium swallow | EGD | Esophageal manometry | Treatment |

| Ramos et al[16] 2009 | 44-yr-old female | 47 | Laparoscopic RYGB | Dysphagia to solids, and regurgitation | 4 yr | Dilated | Normal gastroesophageal | Elevated resting LES pressure, aperistalsis, and hypo contractility | Laparoscopic Heller myotomy |

| esophagus, poor esophageal emptying, and | junction, a 4-cm gastric pouch without lesions, and a wide | of the esophagus. | |||||||

| tapering of the LES | gastrojejunostomy | ||||||||

| Torghabeh et al[17] 2015 | 48-yr-old female | 44.75 | Laparoscopic RYGB | Dysphagia to solid, regurgitation, and chest pain | 5 yr | Dilated esophagus and stricture at the LES | Tortuous esophagus with retained food products and Candida plaques. Stricture was balloon dilated | Elevated resting LES pressure, aperistalsis, and failure of LES relaxation | Laparoscopic Heller myotomy |

| Chapman et al[18] 2013 | 53-yr-old female | NA | Open PYGB | Epigastric and LUQ pain and reflux symptoms | 2 yr | Dilated thoracic esophagus with reduced primary peristalsis. Contrast was slow to pass through the gastro-esophageal junction | Dilated esophagus, esophagitis and ulceration above the gastro-esophageal junction | Absence of LES relaxation and aperistalsis | Laparoscopic Heller myotomy |

| Our case 2016 | 70-yr-old female | 52 | Laparoscopic RYGB | Regurgitation, mild dysphagia, nausea and occasional vomiting | 2 yr | Persistent narrowing of the gastroesophageal junction with a dilated, debris filled esophagus. Some tertiary contractions | Dilated, tortuous esophagus that appeared as a "sigmoid esophagus" but no strictures or stenosis was noted. | Elevated LES pressure with abnormal relaxation in addition to aperistalsis and | Scheduled for laparoscopic Heller myotomy |

Achalasia is a rare esophageal motility disorder that is characterized by neurodegeneration, of the inhibitory nitric oxide-producing neurons. It usually manifests with dysphagia to both solid and liquids and regurgitation. Obesity is a global epidemic and can be associated with esophageal motility disorders. Esophageal motility disorders, including achalasia, occur as a consequence of bariatric surgeries.

Persistent nausea, regurgitation and mild dysphagia to solids and liquids for one month. History of RYGB 2 yr ago with reversal 2 mo prior to presentation.

Hemodynamically stable with normal vital signs. Abdomen was soft, without tenderness to palpation and with bowel sounds present. The wound from her recent surgery was clean, with no evidence of discharge or poor healing.

Distal esophageal stricture, Stenosis of the gastrojejunostomy, achalasia, tumor of the gastric cardia or distal esophagus, infectious gastroenteritis.

Initial complete blood count, basic metabolic panel (kidney function and electrolytes) and liver panel were unremarkable. Stool workup was negative for infection.

A computed tomography scan of the chest with contrast showed enteric contrast within the dilated distal esophagus and was suspicious for a mild stricture at gastroesophageal sphincter . A Barium study was showed persistent narrowing of the gastroesophageal junction with a moderately dilated, debris-filled esophagus proximally and some tertiary esophageal contractions. Manometry was performed 2 wk after discharge and revealed high pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) with abnormal relaxation and high resting pressure, in addition to aperistalsis. These results were consistent with type II achalasia.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed a tortuous and dilated esophagus with large amounts of thick secretions in the esophagus. No strictures, stenosis or evidence of malignancy were noted.

Supportive treatment while inpatient with intravenous fluids and anti-emetics. She was referred for evaluation and laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy after her diagnosis.

Table 1 summarize previous reported cases of achalasia in association with RYGB.

Achalasia is a rare esophageal motility disorder characterized by loss of peristalsis in the distal esophagus and failure of LES.

Achalasia and other esophageal motility disorders may occur as a consequence of bariatric surgeries including RYGB.

A rare case report that achalasia after bariatric Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery was well described by the authors. Only 3 reported cases of achalasia after RYGB had been reported in the world, and this was the first case described after revision of RYGB. It’s a worth case to be reported.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Altarabsheh SE, Wang BM, Garcia-Olmo D S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Pandolfino JE, Kwiatek MA, Nealis T, Bulsiewicz W, Post J, Kahrilas PJ. Achalasia: a new clinically relevant classification by high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1526-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 661] [Cited by in RCA: 551] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sadowski DC, Ackah F, Jiang B, Svenson LW. Achalasia: incidence, prevalence and survival. A population-based study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:e256-e261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fisichella PM, Raz D, Palazzo F, Niponmick I, Patti MG. Clinical, radiological, and manometric profile in 145 patients with untreated achalasia. World J Surg. 2008;32:1974-1979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wong RK, Maydonovitch CL, Metz SJ, Baker JR Jr. Significant DQw1 association in achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:349-352. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Niwamoto H, Okamoto E, Fujimoto J, Takeuchi M, Furuyama J, Yamamoto Y. Are human herpes viruses or measles virus associated with esophageal achalasia? Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:859-864. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Katzka DA, Farrugia G, Arora AS. Achalasia secondary to neoplasia: a disease with a changing differential diagnosis. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:331-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Koppman JS, Poggi L, Szomstein S, Ukleja A, Botoman A, Rosenthal R. Esophageal motility disorders in the morbidly obese population. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:761-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hong D, Khajanchee YS, Pereira N, Lockhart B, Patterson EJ, Swanstrom LL. Manometric abnormalities and gastroesophageal reflux disease in the morbidly obese. Obes Surg. 2004;14:744-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jaffin BW, Knoepflmacher P, Greenstein R. High prevalence of asymptomatic esophageal motility disorders among morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 1999;9:390-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Herbella FA, Matone J, Lourenço LG, Del Grande JC. Obesity and symptomatic achalasia. Obes Surg. 2005;15:713-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cho M, Kaidar-Person O, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Achalasia after vertical banded gastroplasty for morbid obesity: A case report. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16:161-164. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Rubenstein RB. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding at a U.S. center with up to 3-year follow-up. Obes Surg. 2002;12:380-384. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Khan A, Ren-Fielding C, Traube M. Potentially reversible pseudoachalasia after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:775-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Naef M, Mouton WG, Naef U, van der Weg B, Maddern GJ, Wagner HE. Esophageal dysmotility disorders after laparoscopic gastric banding--an underestimated complication. Ann Surg. 2011;253:285-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shah RN, Izanec JL, Friedel DM, Axelrod P, Parkman HP, Fisher RS. Achalasia presenting after operative and nonoperative trauma. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1818-1821. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Ramos AC, Murakami A, Lanzarini EG, Neto MG, Galvão M. Achalasia and laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5:132-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Torghabeh MH, Afaneh C, Saif T, Dakin GF. Achalasia 5 years following Roux-en-y gastric bypass. J Minim Access Surg. 2015;11:203-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chapman R, Rotundo A, Carter N, George J, Jenkinson A, Adamo M. Laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy for achalasia after gastric bypass: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:396-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (2009) Fact Sheet. Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Available from: https://asmbs.org/resources/metabolic-and-bariatric-surgery. |

| 20. | Nguyen NT, Masoomi H, Magno CP, Nguyen XM, Laugenour K, Lane J. Trends in use of bariatric surgery, 2003-2008. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:261-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | NIH conference. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Consensus Development Conference Panel. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:956-961. [PubMed] |

| 22. | O’Rourke RW, Jobe BA, Spight DH, Hunter JG. Simultaneous surgical management of achalasia and morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2007;17:547-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kaufman JA, Pellegrini CA, Oelschlager BK. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a novel operation for the obese patient with achalasia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2005;15:391-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |