Published online Sep 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i35.6371

Peer-review started: July 12, 2017

First decision: August 10, 2017

Revised: August 18, 2017

Accepted: September 5, 2017

Article in press: September 5, 2017

Published online: September 21, 2017

Processing time: 72 Days and 5.9 Hours

A world-wide rise in the prevalence of obesity continues. This rise increases the occurrence of, risks of, and costs of treating obesity-related medical conditions. Diet and activity programs are largely inadequate for the long-term treatment of medically-complicated obesity. Physicians who deliver gastrointestinal care after completing traditional training programs, including gastroenterologists and general surgeons, are not uniformly trained in or familiar with available bariatric care. It is certain that gastrointestinal physicians will incorporate new endoscopic methods into their practice for the treatment of individuals with medically-complicated obesity, although the long-term impact of these endoscopic techniques remains under investigation. It is presently unclear whether gastrointestinal physicians will be able to provide or coordinate important allied services in bariatric surgery, endocrinology, nutrition, psychological evaluation and support, and social work. Obtaining longitudinal results examining the effectiveness of this ad hoc approach will likely be difficult, based on prior experience with other endoscopic measures, such as the adenoma detection rates from screening colonoscopy. As a long-term approach, development of a specific curriculum incorporating one year of subspecialty training in bariatrics to the present training of gastrointestinal fellows needs to be reconsidered. This approach should be facilitated by gastrointestinal trainees’ prior residency training in subspecialties that provide care for individuals with medical complications of obesity, including endocrinology, cardiology, nephrology, and neurology. Such training could incorporate additional rotations with collaborating providers in bariatric surgery, nutrition, and psychiatry. Since such training would be provided in accredited programs, longitudinal studies could be developed to examine the potential impact on accepted measures of care, such as complication rates, outcomes, and costs, in individuals with medically-complicated obesity.

Core tip: A world-wide rise in the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related medical conditions needs to be addressed. Newer endoscopic methods will be incorporated into the clinical practice of gastrointestinal physicians, although the long-term impact of these endoscopic methods on medically-complicated obesity remains under investigation. As a potential long-term approach, development of a curriculum designed to incorporate one year of subspecialty training in bariatrics to the present training of gastrointestinal fellows needs to be reconsidered. Longitudinal studies could be performed to examine the impact of subspecialty training on medical complications, outcomes, and costs in treating individuals with medically-complicated obesity.

- Citation: Koch TR, Shope TR, Gostout CJ. Organization of future training in bariatric gastroenterology. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(35): 6371-6378

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i35/6371.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i35.6371

The rising prevalence of obesity is a worldwide disorder, and therefore this problem will require a collaborative global approach. One commonly utilized definition of overweight and obesity is based upon the body mass index or BMI, which is calculated from an individual’s height and weight (see Table 1). An extensive study has shown that the worldwide percentage of adults who are overweight (BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2) or obese (BMI 30.0 and higher) increased from 28.8% of men in 1980 to 36.9% of men in 2013, and increased from 29.8% of women in 1980 to 38.0% of women in 2013[1]. Based on their data, the authors by extrapolation estimated that 2.1 billion individuals were overweight or obese by 2013. Similar results were recently reported in a study of 195 countries[2]. In more than 70 countries, the prevalence of obesity has doubled since 1980[2].

| BMI (kg/m2) | Definition | Obesity class |

| 18.5-24.9 | Normal | |

| 25-29.9 | Overweight | |

| 30-34.9 | Obesity | I |

| 35-39.9 | Obesity | II |

| 40.0- | Obesity | III |

Obesity-related medical conditions (see Table 2) include insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus, obstructive sleep apnea, mechanical or degenerative osteoarthritis, non-alcohol steatohepatitis, hypertension, dyslipidemia with secondary coronary artery disease, pseudo-tumor cerebri, and likely gastroesophageal reflux, deep vein thrombosis, and asthma[3]. Obesity has also been consistently associated with increased risk of kidney, breast, endometrial, colorectal, pancreatic, esophageal, and gall bladder carcinoma[4]. Excess body weight contributes to a significant percentage of cases of cancer[4]. With the increase in the incidence of obesity in Asia, The Gut and Obesity in Asia Workgroup has developed an experts’ consensus on obesity and gastrointestinal diseases in Asia[5]. In a worldwide systematic review, it was reported that obesity accounts for 0.7% to 2.8% of a country’s total healthcare expenditures and that individuals with obesity have at least 30% higher healthcare costs[6]. In the United States, the medical care costs of obesity in 2008 were estimated to be $147 billion[7].

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Obstructive sleep apnea |

| Degenerative osteoarthritis |

| Non-alcohol steatohepatitis |

| Hypertension |

| Dyslipidemia with coronary artery disease |

| Pseudo-tumor cerebri |

| Gastroesophageal reflux |

| Deep vein thrombosis |

| Asthma |

| Carcinomas (kidney, breast, endometrial, colorectal, pancreatic, esophageal, gallbladder) |

As one can ascertain from this rise in the worldwide prevalence of obesity, the previously suggested solutions with regards to this serious medical problem have not been effective. One suggested approach is education, with the inference that individuals will then make responsible choices when eating several times every day[8]. In the United States, the National Institutes of Health and the United States Preventive Services Task Force in 1998 and in 2012 suggested behavioral interventions, increased physical activity, and improved dietary intake[9,10]. Expectations of results from these recommendations however must be balanced against the findings of multiple meta-analyses[11-13] that have examined the potential benefits of behavioral interventions, diet and activity programs in individuals with excess weight. Reported “long term” results are for studies of only 12 to 18 mo. Unfortunately, the published weight loss results are modest with 1.5 to 5 kg of weight loss at 12 mo[11] after adopting behavioral interventions (which can include self-monitoring, setting weight loss goals, addressing barriers to change, and strategizing long-term change in lifestyle). These meta-analyses mention that there is higher weight loss reported for those individuals participating in dietary only programs compared to individuals involved in exercise or activity only programs. Combined dietary and physical activity programs tailored to individual metabolic and dietary response needs appear to be more beneficial than solely dietary programs. However, adding physical activity programs appear to increase overall weight loss by only an additional 0 to 3 kg.

Our review of previous contributions in this field included specific searches on PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) on June 11, 2017. The terms “gastroenterology fellow training” yielded 111 abstracts; the terms “gastroenterology fellow nutrition” yielded 35 abstracts; the terms “gastroenterology fellow obesity” yielded 8 abstracts; the terms “nutrition training gastrointestinal medicine” yielded 251 abstracts; and the terms “obesity training gastrointestinal medicine” yielded 97 abstracts. All abstracts and all manuscripts consistent with the topic of this present manuscript were reviewed by one of us (TRK).

Gastrointestinal physicians and general surgeons both deliver gastrointestinal care to individuals with medically-complicated obesity, including the performance of endoscopy. These physicians, after completing traditional training programs, are uniformly trained in or familiar with available bariatric care. This notion is not a new concern. A survey of gastroenterologists published in 1976 revealed that obesity was included as one of the five most common diagnostic areas[14]. The author suggested that his findings could be the basis for planning education, training, and research activities in gastroenterology. An editorial published 26 years later described a commitment of the American Gastroenterological Association to nutrition and obesity, including a summary of elements included in advanced or level 2 training in nutrition[15]. A 2006 study in Canada of gastrointestinal clinicians and gastrointestinal fellows reconfirmed the opinion that training in management of obesity was inadequate[16]. A follow-up survey of Canadian gastrointestinal fellows published in 2009 revealed that gastrointestinal fellows considered their knowledge of nutrition and obesity to be suboptimal[17]. A written examination completed by these gastrointestinal fellows confirmed that their knowledge base indeed was suboptimal, especially in the areas of nutritional support, knowledge of micronutrients and macronutrients, obesity, and nutrition in gastrointestinal diseases. Similar findings have been reported in studies of gastrointestinal fellows in Iran[18] and in the United States[19]. One response to these long-standing concerns and weaknesses in nutrition training has been the publication of a potentially extensive curriculum in nutrition as part of the core curriculum for fellows or trainees in gastroenterology[20].

Training of gastrointestinal fellows internationally has involved programs with a traditional pathway which include disease-related training and endoscopy[21], and programs that combine basic elements of gastrointestinal training with time for advanced training in a subspecialty of gastroenterology or hepatology.

The traditional involvement of gastrointestinal clinicians in obesity has involved two levels of medical care: (1) direct care of gastrointestinal medical disorders related to obesity including non-alcohol steatohepatitis, gastroesophageal reflux, colorectal carcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma, esophageal carcinoma, and gall bladder carcinoma; and (2) consultants in collaboration with providers who treat patients for obesity, for example in the care of individuals who have undergone bariatric surgery. More recently, due to advances in therapeutic endoscopy, gastrointestinal physicians have begun to assume a role as the provider directly treating individuals for obesity. The question to now be considered is what pathways should be utilized to expand the role of gastrointestinal physicians in the care of individuals with medically-complicated obesity.

There are two major approaches for a process by which gastrointestinal physicians can evolve into physicians with primary responsibility for the treatment of individuals with medically-complicated obesity. A recent White Paper from the American Gastroenterology Association proposes incorporation of methods for obesity care and “weight management” into existing gastroenterological practices[22]. This approach immediately raises the question of how much weight loss is required for the appropriate treatment of medically-complicated obesity. An overview of treatment of individuals with non-alcohol steatohepatitis summarizes a proposed goal of loss of 10% of total body weight[23]. This weight loss goal can be difficult to reach in individuals with obesity through the use of dietary and activity programs. In agreement with recently published meta-analyses[11-13], a recent study from Cuba again demonstrated that only 10% of participants involved in dietary and activity programs were able to lose 10% or more of their total body weight[24]. Again in agreement with ongoing experience[23], liver biopsies revealed that 90% of the participants who lost 10% or more of their total body weight had resolution of non-alcohol steatohepatitis. This study did not address the follow up concern which of course is long-term maintenance of weight loss, or an individual’s weight regain.

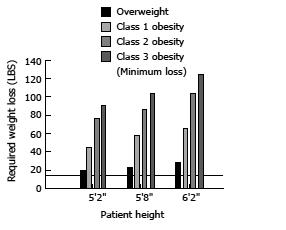

When considering treatment of individuals with medically-complicated obesity, Figure 1 summarizes weight loss (in pounds) required to reach the normal weight range in overweight individuals and in obese individuals of difference heights. The solid line approximates the best published weight loss obtained through dietary and activity programs. Figure 1 provides a graphic depiction of the extent of weight loss required to improve serious medical disorders in individuals with Type II obesity and Type III obesity. For this reason, we have previously suggested that bariatric surgery utilizing vertical sleeve gastrectomy will likely become a major consideration for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in those individuals with Type II obesity and Type III obesity[25].

As step-up therapy for the treatment of medically-complicated obesity, the United States Food and Drug Administration has approved nine medical therapies for weight loss (see Table 3)[26-29]. There are four sympathomimetic drugs, which increase adrenergic stimulus, that have been approved for short term (12 wk) of medical therapy. This group includes Benzphetamine, Diethylpropion, Phendimetrazine, and Phentermine. There are five medical therapies approved for long-term medical therapy, which includes Orlistat, Liraglutide, Lorcaserin, Naltrexone with Bupropion, and Phentermine with Topiramate. As shown in Table 3, the published weight loss results reported for these medications are modest, ranging from 2.6 to 8.8 kg. Prescribing providers should be familiar with the significant risks involved in using these medications. For example, Orlistat can lead to deficiencies of fat soluble vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, and vitamin K. Lorcaserin should not be used with monoamine oxidase inhibitors or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Topiramate is associated with oral clefts when taken by pregnant women.

| Medication | Published weight loss |

| Short term use | Range from 3.6 to 8.1 kg |

| Benzphetamine | |

| Diethylpropion | |

| Phendimetrazine | |

| Phentermine | |

| Long term use | |

| Orlistat | 2.6 kg |

| Liraglutide | 4 to 6 kg |

| Lorcaserin | 3.2 kg |

| Naltrexone and bupropion | 5 kg |

| Phentermine and topiramate | 8.8 kg |

The next available step-up therapies for treatment of medically-complicated obesity involve the utilization of newer endoscopic techniques that are now available. These techniques can be divided into either the delivery of a weight loss device or the use of intralumenal suturing to promote weight loss[30] (see Table 4). Individualized care with scheduled post-procedural follow up is important for long-term optimization of an endoscopic weight loss program, as has been supported by studies of adjustable gastric banding[31]. Individuals might also benefit from transition to the use of a well selected long-term weight loss medication.

| Method | Potential physiological mechanisms |

| Delivery of a Weight Loss Device | |

| Intragastric Balloon | Stomach distension; reduce volume required for satiety; delay gastric emptying |

| Orbera1 | |

| ReShape1 | |

| Obalon1 | |

| Duodeno-jejunal bypass sleeve | Delay Gastric Emptying; Induce Malabsorption |

| Aspiration therapy | Reduce Intragastric Nutrients |

| Use of intraluminal suturing | |

| Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty | Induce early satiation; delay gastric emptying |

| Transoral gastroplasty | Reduce volume required for satiety |

Upper endoscopy has been utilized for placement of an intragastric balloon, a duodeno-jejunal bypass sleeve, or an aspiration tube. Other than The AspireAssist described below, all of these devices are meant to be removed at 6 to 12 mo after their placement. The United States Food and Drug Administration approved the first intragastric balloon, the Garren-Edwards bubble in 1985. Interest in intragastric balloon has grown due to the United States Food and Drug Administration’s approval of 3 separate intragastric balloon systems in the past 2 years: the Orbera balloon, the ReShape balloon, and the Obalon balloon. All three balloon systems must be removed after 6 mo. Clinical research has examined factors important for weight loss with the use of an intragastric balloon[32]. The mechanism for weight loss from the fluid filled intra-gastric balloon, e.g., delayed gastric emptying, has also been identified[33]. A duodenojejunal bypass sleeve, EndoBarrier, (GI Dynamics, Inc., Lexington, MA, United States) is available in some countries. This bypass sleeve is a fluoroscopically assisted and endoscopically implanted, removable, and impermeable fluoropolymer sleeve with a nitinol anchor. At upper endoscopy, the 60 cm long device is deployed from the duodenal bulb and into the jejunum under fluoroscopic guidance. In 2016, the United States Food and Drug Administration approved The AspireAssist produced by Aspire Bariatrics, King of Prussia, PA, United States which provides a long term option for patients in the higher body mass index range. At upper endoscopy, a specialized aspiration tube is placed percutaneously into the stomach. This aspiration tube has both an intragastric portion with holes to permit aspiration as well as a skin port. Individuals with an aspiration tube are instructed to aspirate their gastric contents 20 min after a meal containing more than 200 kcal. The device is not meant to be placed in an individual with an eating disorder.

The endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG), first reported from the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States in 2013, has eclipsed all prior failed efforts at altering the gastric lumen endoscopically[34,35]. There have been over 2500 ESG procedures performed worldwide with patient follow-up now exceeding 2 years, and a recent multicenter study using this technique to produce an endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty reported 24-mo weight loss data[36]. Publications with individual and multicenter experiences are appearing and demonstrate not only sustained weight loss but improvement in co-morbidities. There is also published experience discussing mechanisms by which ESG is important a patients’ weight loss[37]. Others[38,39] are attempting to duplicate successful weight loss using technologies differing from the existing endoscopic suturing device (OverStitch, Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, TX, United States) presently used for the ESG.

The advantages of development of an endoscopic procedure to mimic the popular and effective vertical sleeve gastrectomy are clear, e.g. reduced risk of anesthesia and reduced risk of a gastric leak or perforation. The importance of obtaining long term weight loss data to support durability is supported by results from the surgical literature. In the original report from the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States of the surgical non-banded vertical gastroplasty, at 4 years of follow up, only 31% of patients were judged to have persistent excess weight lost[40]. In additional studies, risk factors important for treatment failures after vertical gastroplasty were examined[41]. Even with the availability of this information, a study (published 16 years later) involving seven years of follow up after vertical banded gastroplasty reported staple line disruption in 54% of patients[42]. Sixty percent of patients after vertical banded gastroplasty underwent a major re-operation during this seven year follow up period.

After practicing gastrointestinal physicians in-corporate these newer endoscopic techniques into their care of individuals with obesity, a major question will arise as to whether reliable follow up will be obtained. In examination of other endoscopic quality measures, the recommendation that endoscopists should track their adenoma detection rates from screening colonoscopy has been supported by results of interval cancers published in 2010[43]. However, in a 2015 survey of training programs in the United States, 63.8% of programs did not assess adenoma detection rates in their trainees[44]. It is similarly likely that it will be difficult to obtain longitudinal results designed to examine the effectiveness of an ad hoc approach for incorporation into an established gastrointestinal practice of new endoscopic methods for treating individuals with medically-complicated obesity.

It is expected[45] that physicians providing bariatric care will properly evaluate, diagnose, and treat individuals who develop complications from their weight loss therapy.

Prevention of complications from weight loss therapy begins by screening patients for their suitability to undergo treatment of medically-complicated obesity. Gastrointestinal physicians will need to decide how they will integrate physiologic (e.g, low satiety or rapid gastric emptying), psychological, or psychiatric assessment of eating disorders and underlying psychiatric illness into their practice. For example, it is reported that the prevalence of obesity is higher individuals with schizophrenia[46,47].

Following bariatric surgery, a Danish study has described increased risks of self-harm, psychiatric service use, and the occurrence of mental disorders[48]. With regards to the potential for addiction, persistent opioid abuse can result from even minor surgical procedures[49]. A systematic review of postoperative bariatric patients suggested the presence of increased alcohol use and increased admissions to substance abuse treatment facilities[50]. Physicians involved in primary weight loss therapy will need a program to screen for these potential problems and regimens for appropriate and sufficient treatment.

A second, long-term approach for incorporation of bariatric care into gastrointestinal practice would involve adaptation of the training of gastrointestinal fellows for treatment of and long-term control of medically-complicated obesity. Such an approach is supported by studies demonstrating improved bariatric outcomes in hospitals with accredited bariatric fellowships[51]. The evolution of a field of medicine requires individuals who focus on the evaluation of alteration of proposed methods and treatments. This potential approach should be facilitated by the gastrointestinal trainees’ prior internal medicine residency training in subspecialties that provide care for individuals with medical complications of obesity, including endocrinology, cardiology, nephrology, and neurology. It is expected that gastrointestinal fellows trained in advanced endoscopy should be capable of learning the proper application of most endoscopic techniques for weight loss therapy in individuals with medically-complicated obesity. Gastrointestinal fellows will also need training to manage post-operative complications (e.g., leaks, fistulas, and endolumenal revision of the Roux en Y gastric bypass and the sleeve gastrectomy) in patients who have undergone bariatric surgery.

The training time commitment would depend upon the specific bariatric care that the future ga-strointestinal physician would plan to deliver. The issue of development of a curriculum incorporating one year of subspecialty training in bariatrics to the present training of gastrointestinal fellows needs to be revisited. A one year period of subspecialty training in bariatrics could incorporate additional rotations with collaborating providers in bariatric medicine, bariatric surgery, nutrition, and psychiatry. The trainees could then be instructed in postoperative care of patients who have undergone bariatric surgery. Trainees could be trained in the management of adjustable gastric bands, postoperative nutritional disorders[52], postoperative symptoms and, as mentioned above, complications after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery[3], and the management of major complications of vertical sleeve gastrectomy including gastric perforation or leak[53] and vomiting/dysphagia[54].

As an advantage of this potential organization, since such training would be provided in accredited programs, longitudinal studies could be developed to examine the potential impact on accepted measures of care, such as complication rates, outcomes, and costs, in individuals with medically-complicated obesity.

The prevalence of obesity continues to rise worldwide. This rise increases the incidence of obesity-related diseases, and these obesity-related diseases are an important component of health care costs in countries across the world. Diet and activity programs are largely inadequate for the long-term treatment of medically-complicated obesity. Gastrointestinal physicians to date have not been extensively involved in weight loss programs in individuals with medically-complicated obesity. It is certain that gastrointestinal physicians will incorporate new methods into their endoscopic practice for treatment of individuals with medically-complicated obesity. This change will involve incorporation of new endoscopic techniques into present gastrointestinal practices. Improved bariatric care will likely require an organized curriculum in gastrointestinal training programs. Involvement in weight loss programs induces significant psycho-social disorders. Obtaining optimal results will require practice patterns that screen for recognized pre-disposing gastric physiological disorders and psycho-social disorders, and develop ongoing protocols for the management of complications of bariatric care. Optimizing strategies for the long-term maintenance of weight loss after the use of newer endoscopic techniques remain important ongoing issues.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fogli L, Milone M, Tarnawski AS S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, Biryukov S, Abbafati C, Abera SF. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7951] [Cited by in RCA: 8006] [Article Influence: 727.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators, Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, Lee A, Marczak L, Mokdad AH, Moradi-Lakeh M, Naghavi M, Salama JS, Vos T, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Ahmed MB, Al-Aly Z, Alkerwi A, Al-Raddadi R, Amare AT, Amberbir A, Amegah AK, Amini E, Amrock SM, Anjana RM, Ärnlöv J, Asayesh H, Banerjee A, Barac A, Baye E, Bennett DA, Beyene AS, Biadgilign S, Biryukov S, Bjertness E, Boneya DJ, Campos-Nonato I, Carrero JJ, Cecilio P, Cercy K, Ciobanu LG, Cornaby L, Damtew SA, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dharmaratne SD, Duncan BB, Eshrati B, Esteghamati A, Feigin VL, Fernandes JC, Fürst T, Gebrehiwot TT, Gold A, Gona PN, Goto A, Habtewold TD, Hadush KT, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hay SI, Horino M, Islami F, Kamal R, Kasaeian A, Katikireddi SV, Kengne AP, Kesavachandran CN, Khader YS, Khang YH, Khubchandani J, Kim D, Kim YJ, Kinfu Y, Kosen S, Ku T, Defo BK, Kumar GA, Larson HJ, Leinsalu M, Liang X, Lim SS, Liu P, Lopez AD, Lozano R, Majeed A, Malekzadeh R, Malta DC, Mazidi M, McAlinden C, McGarvey ST, Mengistu DT, Mensah GA, Mensink GBM, Mezgebe HB, Mirrakhimov EM, Mueller UO, Noubiap JJ, Obermeyer CM, Ogbo FA, Owolabi MO, Patton GC, Pourmalek F, Qorbani M, Rafay A, Rai RK, Ranabhat CL, Reinig N, Safiri S, Salomon JA, Sanabria JR, Santos IS, Sartorius B, Sawhney M, Schmidhuber J, Schutte AE, Schmidt MI, Sepanlou SG, Shamsizadeh M, Sheikhbahaei S, Shin MJ, Shiri R, Shiue I, Roba HS, Silva DAS, Silverberg JI, Singh JA, Stranges S, Swaminathan S, Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Tadese F, Tedla BA, Tegegne BS, Terkawi AS, Thakur JS, Tonelli M, Topor-Madry R, Tyrovolas S, Ukwaja KN, Uthman OA, Vaezghasemi M, Vasankari T, Vlassov VV, Vollset SE, Weiderpass E, Werdecker A, Wesana J, Westerman R, Yano Y, Yonemoto N, Yonga G, Zaidi Z, Zenebe ZM, Zipkin B, Murray CJL. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:13-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5669] [Cited by in RCA: 5073] [Article Influence: 634.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Bal B, Koch TR, Finelli FC, Sarr MG. Managing medical and surgical disorders after divided Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:320-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Brenner DR, Poirier AE, Grundy A, Khandwala F, McFadden A, Friedenreich CM. Cancer incidence attributable to excess body weight in Alberta in 2012. CMAJ Open. 2017;5:E330-E336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Koh JC, Loo WM, Goh KL, Sugano K, Chan WK, Chiu WY, Choi MG, Gonlachanvit S, Lee WJ, Lee WJ. Asian consensus on the relationship between obesity and gastrointestinal and liver diseases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:1405-1413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Withrow D, Alter DA. The economic burden of obesity worldwide: a systematic review of the direct costs of obesity. Obes Rev. 2011;12:131-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 750] [Cited by in RCA: 632] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:w822-w831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1801] [Cited by in RCA: 1599] [Article Influence: 99.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Meldrum DR, Morris MA, Gambone JC. Obesity pandemic: causes, consequences, and solutions-but do we have the will? Fertil Steril. 2017;107:833-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 33.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6 Suppl 2:51S-209S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 890] [Cited by in RCA: 763] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Moyer VA; U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for and management of obesity in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:373-378. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Johns DJ, Hartmann-Boyce J, Jebb SA, Aveyard P; Behavioural Weight Management Review Group. Diet or exercise interventions vs combined behavioral weight management programs: a systematic review and meta-analysis of direct comparisons. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:1557-1568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Verheggen RJ, Maessen MF, Green DJ, Hermus AR, Hopman MT, Thijssen DH. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of exercise training versus hypocaloric diet: distinct effects on body weight and visceral adipose tissue. Obes Rev. 2016;17:664-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Clark JE. Diet, exercise or diet with exercise: comparing the effectiveness of treatment options for weight-loss and changes in fitness for adults (18-65 years old) who are overfat, or obese; systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;14:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Switz DM. What the gastroenterologist does all day. A survey of a state society’s practice. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:1048-1050. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Klein S. Why should gastroenterologists be interested in nutrition and obesity? Gastroenterology. 2002;123:967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Singh H, Duerksen DR. Survey of clinical nutrition practices of Canadian gastroenterologists. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:527-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Raman M, Violato C, Coderre S. How much do gastroenterology fellows know about nutrition? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:559-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Eslamian G, Jacobson K, Hekmatdoost A. Clinical nutrition knowledge of gastroenterology fellows: is there anything omitted? Acta Med Iran. 2013;51:633-637. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Scolapio JS, Buchman AL, Floch M. Education of gastroenterology trainees: first annual fellows’ nutrition course. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:122-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mulder CJ, Wanten GJ, Semrad CE, Jeppesen PB, Kruizenga HM, Wierdsma NJ, Grasman ME, van Bodegraven AA. Clinical nutrition in the hepatogastroenterology curriculum. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1729-1735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hatanaka H, Yamamoto H, Lefor AK, Sugano K. Gastro-enterology Training in Japan. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:1448-1450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Acosta A, Streett S, Kroh MD, Cheskin LJ, Saunders KH, Kurian M, Schofield M, Barlow SE, Aronne L. White Paper AGA: POWER - Practice Guide on Obesity and Weight Management, Education, and Resources. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:631-649.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hsu CC, Ness E, Kowdley KV. Nutritional Approaches to Achieve Weight Loss in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Adv Nutr. 2017;8:253-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, Torres-Gonzalez A, Gra-Oramas B, Gonzalez-Fabian L, Friedman SL, Diago M, Romero-Gomez M. Weight Loss Through Lifestyle Modification Significantly Reduces Features of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:367-378.e5; quiz e14-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1181] [Cited by in RCA: 1629] [Article Influence: 162.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Hsueh W, Shope TR, Koch TR, Smith CI. Bariatric surgery for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Is vertical sleeve gastrectomy the best future option? J Gastroent Hepatol Res. 2016;5:1957-1961. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mehta A, Marso SP, Neeland IJ. Liraglutide for weight management: a critical review of the evidence. Obes Sci Pract. 2017;3:3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Khera R, Murad MH, Chandar AK, Dulai PS, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Loomba R, Camilleri M, Singh S. Association of Pharmacological Treatments for Obesity With Weight Loss and Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315:2424-2434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 655] [Cited by in RCA: 556] [Article Influence: 61.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Joo JK, Lee KS. Pharmacotherapy for obesity. J Menopausal Med. 2014;20:90-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Velazquez A, Apovian CM. Pharmacological management of obesity. Minerva Endocrinol. 2017; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rashti F, Gupta E, Ebrahimi S, Shope TR, Koch TR, Gostout CJ. Development of minimally invasive techniques for management of medically-complicated obesity. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13424-13445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Schouten R, van’t Hof G, Feskens PB. Is there a relation between number of adjustments and results after gastric banding? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:908-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kotzampassi K, Shrewsbury AD, Papakostas P, Penna S, Tsaousi GG, Grosomanidis V. Looking into the profile of those who succeed in losing weight with an intragastric balloon. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2014;24:295-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Gómez V, Woodman G, Abu Dayyeh BK. Delayed gastric emptying as a proposed mechanism of action during intragastric balloon therapy: Results of a prospective study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24:1849-1853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Abu Dayyeh BK, Rajan E, Gostout CJ. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty: a potential endoscopic alternative to surgical sleeve gastrectomy for treatment of obesity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:530-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sharaiha RZ, Kumta NA, Saumoy M, Desai AP, Sarkisian AM, Benevenuto A, Tyberg A, Kumar R, Igel L, Verna EC. Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty Significantly Reduces Body Mass Index and Metabolic Complications in Obese Patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:504-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lopez-Nava G, Sharaiha RZ, Vargas EJ, Bazerbachi F, Manoel GN, Bautista-Castaño I, Acosta A, Topazian MD, Mundi MS, Kumta N. Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty for Obesity: a Multicenter Study of 248 Patients with 24 Months Follow-Up. Obes Surg. 2017; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Abu Dayyeh BK, Acosta A, Camilleri M, Mundi MS, Rajan E, Topazian MD, Gostout CJ. Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty Alters Gastric Physiology and Induces Loss of Body Weight in Obese Individuals. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:37-43.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Espinós JC, Turró R, Mata A, Cruz M, da Costa M, Villa V, Buchwald JN, Turró J. Early experience with the Incisionless Operating Platform™ (IOP) for the treatment of obesity: the Primary Obesity Surgery Endolumenal (POSE) procedure. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1375-1383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Miller K, Turró R, Greve JW, Bakker CM, Buchwald JN, Espinós JC. MILEPOST Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial: 12-Month Weight Loss and Satiety Outcomes After pose SM vs. Medical Therapy. Obes Surg. 2017;27:310-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Hocking MP, Kelly KA, Callaway CW. Vertical gastroplasty for morbid obesity: clinical experience. Mayo Clin Proc. 1986;61:287-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Pekkarinen T, Koskela K, Huikuri K, Mustajoki P. Long-term Results of Gastroplasty for Morbid Obesity: Binge-Eating as a Predictor of Poor Outcome. Obes Surg. 1994;4:248-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Schouten R, Wiryasaputra DC, van Dielen FM, van Gemert WG, Greve JW. Long-term results of bariatric restrictive procedures: a prospective study. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1617-1626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Zwierko M, Rupinski M, Nowacki MP, Butruk E. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1795-1803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1287] [Cited by in RCA: 1468] [Article Influence: 97.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Patel SG, Keswani R, Elta G, Saini S, Menard-Katcher P, Del Valle J, Hosford L, Myers A, Ahnen D, Schoenfeld P. Status of Competency-Based Medical Education in Endoscopy Training: A Nationwide Survey of US ACGME-Accredited Gastroenterology Training Programs. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:956-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Tuchtan L, Kassir R, Sastre B, Gouillat C, Piercecchi-Marti MD, Bartoli C. Medico-legal analysis of legal complaints in bariatric surgery: a 15-year retrospective study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:903-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Li Q, Du X, Zhang Y, Yin G, Zhang G, Walss-Bass C, Quevedo J, Soares JC, Xia H, Li X. The prevalence, risk factors and clinical correlates of obesity in Chinese patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:131-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Breland JY, Phibbs CS, Hoggatt KJ, Washington DL, Lee J, Haskell S, Uchendu US, Saechao FS, Zephyrin LC, Frayne SM. The Obesity Epidemic in the Veterans Health Administration: Prevalence Among Key Populations of Women and Men Veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:11-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kovacs Z, Valentin JB, Nielsen RE. Risk of psychiatric disorders, self-harm behaviour and service use associated with bariatric surgery. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135:149-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, Moser S, Lin P, Englesbe MJ, Bohnert ASB, Kheterpal S, Nallamothu BK. New Persistent Opioid Use After Minor and Major Surgical Procedures in US Adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:e170504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1409] [Cited by in RCA: 1555] [Article Influence: 194.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Spadola CE, Wagner EF, Dillon FR, Trepka MJ, De La Cruz-Munoz N, Messiah SE. Alcohol and Drug Use Among Postoperative Bariatric Patients: A Systematic Review of the Emerging Research and Its Implications. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:1582-1601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Kim PS, Telem DA, Altieri MS, Talamini M, Yang J, Zhang Q, Pryor AD. Bariatric outcomes are significantly improved in hospitals with fellowship council-accredited bariatric fellowships. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:594-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Bal BS, Finelli FC, Shope TR, Koch TR. Nutritional deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8:544-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Joo MK. Endoscopic Approach for Major Complications of Bariatric Surgery. Clin Endosc. 2017;50:31-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Nath A, Yewale S, Tran T, Brebbia JS, Shope TR, Koch TR. Dysphagia after vertical sleeve gastrectomy: Evaluation of risk factors and assessment of endoscopic intervention. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:10371-10379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |