Published online Jun 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i24.4462

Peer-review started: February 9, 2017

First decision: March 3, 2017

Revised: March 21, 2017

Accepted: May 19, 2017

Article in press: May 19, 2017

Published online: June 28, 2017

Processing time: 143 Days and 19.2 Hours

Traditional serrated adenoma (TSA) is a type of serrated polyp of the colorectum and is thought to be a precancerous lesion. There are three types of serrated polyps, namely, hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas/polyps, and TSAs. TSA is the least common of the three types and accounts for about 5% of serrated polyps. Here we report a pediatric case of TSA that was successfully resected by endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). This rare case report describes a pediatric patient with no family history of colonic polyp who was admitted to our hospital with hematochezia. On colonoscopy, we found a polypoid lesion measuring 10 mm in diameter in the lower rectum. We selected ESD as a surgical option for en bloc resection, and histopathological examination revealed TSA. The findings in this case suggest that TSA with precancerous potential can occur in children, and that ESD is useful for treating this lesion.

Core tip: Most pediatric colonic polyps are juvenile polyps, and the prevalence of colorectal serrated lesions in this age group is unknown. This case report describes a rare pediatric traditional serrated adenoma that was removed by en bloc resection via endoscopic submucosal dissection.

- Citation: Kondo S, Mori H, Nishiyama N, Kondo T, Shimono R, Okada H, Kusaka T. Case of pediatric traditional serrated adenoma resected via endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(24): 4462-4466

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i24/4462.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i24.4462

Pediatric colorectal polyps mostly occur in young children, and some studies have reported cases of adenoma or adenomatous changes in juvenile polyps[1-3]. However, colorectal adenomas are rare in children and their malignant potential is unclear[4,5].

Serrated colorectal lesions are classified as hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with or without cytologic dysplasia, and traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs). The subtypes of these lesions are identified based on their location and architectural and pathological features.

Lesions ≤ 20 mm can often be removed en bloc by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has recently been developed as a treatment for larger lesions in adults.

Here we report a rare pediatric case of TSA that was successfully resected via ESD.

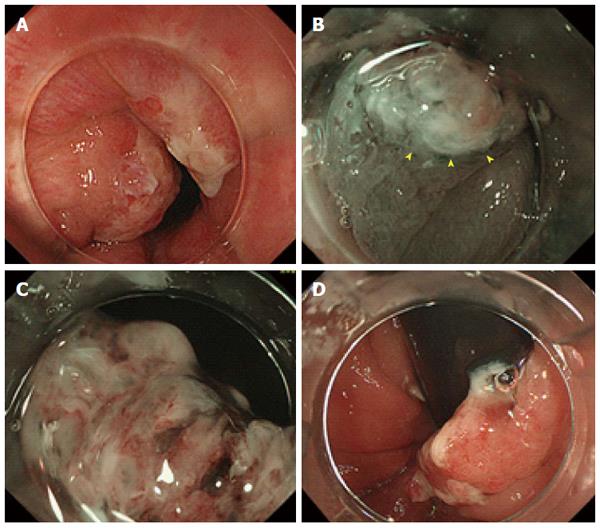

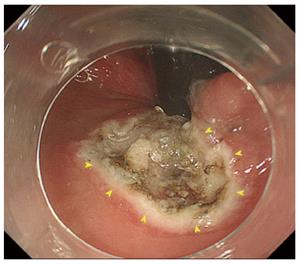

A 12-year-old boy was referred to our hospital with a 4-month history of hematochezia but no other symptoms. He had no relevant medical history, and there was no family history of colorectal polyps or cancer. On admission, the patient underwent colonoscopy under general anesthesia (midazolam 0.3 mg/kg and ketamine 1.0 mg/kg) with bowel preparation (oral polyethylene glycol lavage, 1500 mL). The colonoscopy revealed an elevated polypoid lesion measuring 10 mm in diameter in the lower rectum (Figure 1A). Magnified narrow-band imaging showed the lesion to be composed of whitish mucosal adhesions and slightly reddish villi. The surface of the lesion contained areas of abrasion and necrosis, but because of passage of stool across the lesion it was not possible to examine the pit pattern in detail (Figure 1B and C). Because part of the lesion was located in the anal verge (Figure 1D), we decided that EMR would be inappropriate for en bloc resection and would not obtain an adequate specimen for pathological analysis. Therefore, ESD was carried out using a GIF-H260Z endoscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) approaching from the anal verge. A transparent hood was attached to the tip of the endoscope. The electrosurgical unit comprised a KD-650Q Dualknife (Olympus) and a VIO 300 D generator module (Erbe Elektromedizin GmbH, Tübingen, Germany). Physiological saline with indigo carmine dye was used as the injection solution. After a third of the anal side of the lesion had been dissected, the dissection was completed successfully under a retroflexed view (Figure 2). The procedure time was 22 min.

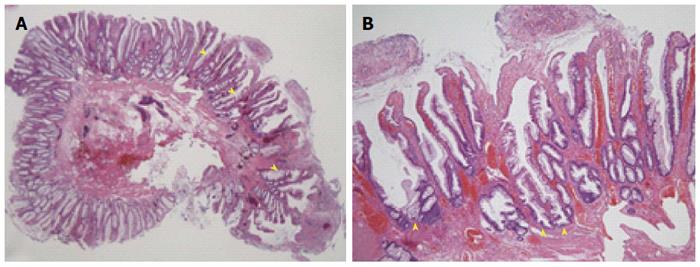

Histopathological examination using hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining (× 10) revealed a TSA (Figure 3A). HE-stained sections (× 100) showed dysplastic changes and an increased number of crypt goblet cells (Figure 3B). A higher power view of the HE-stained sections (× 200) showed pseudostratification of nuclei together with dysplastic changes in the crypt structures of the lesion. All the cut surfaces were negative for neoplastic changes.

No other polyps were observed during an examination that extended up to the terminal ileum. No complications related to the endoscopic procedure were noted. Lidocaine ointment applied to the anal verge successfully prevented postoperative anal pain. The patient resumed eating on the second day after ESD, and was discharged as planned on postoperative day 2. At the time of writing, the patient remains well with no signs of recurrence at 10 mo after discharge.

This patient’s clinical course highlights two important clinical issues, i.e., that TSA can occur in children and that ESD is useful for treating this lesion. Most pediatric colorectal polyps are of the juvenile type; however, the prevalence of pediatric adenomas remains unclear. Thakkar et al[1] reported that 91 (70.5%), 20 (15.5%), 14 (10.9%), and 4 (3.1%) of 122 pediatric cases of colorectal polyps were solitary juvenile polyps, multiple juvenile polyps, adenoma, and hyperplasia, respectively. In contrast, Gupta et al[2] and Latt et al[3] each encountered only 1 case of adenoma in 195 and 730 pediatric cases of colorectal polyps, respectively. These reports did not describe the pathological features of these lesions in detail, so the frequency of serration is unclear.

Saito et al[6] have reported on the endoscopic features of serrated lesions. TSAs occur primarily on the left side of the colon and can produce “pine cone-shaped” lesions. On magnified endoscopic images, TSA can exhibit the IIIH, IVH, or IV-serrated types of pit pattern. Hyperplastic polyps are small pale lesions with obscure boundaries whereas sessile serrated adenomas/polyps are > 10 mm in diameter and found on the right side of the colon together with yellowish thick mucosal adhesions.

Pathologically, TSAs have a complex and distorted tubulovillous configuration with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and basally or centrally located slightly elongated nuclei. The characteristic findings of TSAs include the presence of goblet cells, upper zone mitosis, and prominent nucleoli, and the absence of a thickened collagen table. Hyperplastic polyps are characterized by the presence of straight crypts without significant distortion, and serration is observed in the upper half of the polyp and on its surface rather than at the base. Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps show crypt dilatation, irregularly branching crypts, and horizontally branching boot-shaped, inverted T-shaped, and/or L-shaped crypts. In our case, the surface of the lesion contained areas of abrasion and necrosis, but because of stool passing across the lesion, it was difficult to confirm the characteristic endoscopic findings of TSA. Finally, we diagnosed the polyp as a TSA based on its location, architecture, and pathological features.

ESD was useful for treating TSA in our patient. EMR, which involves a combination of snare polypectomy and submucosal fluid injection, is indicated for the treatment of colorectal adenomas and superficial intramucosal and submucosal tumors. Lesions ≤ 20 mm in diameter can be removed en bloc. In contrast, ESD is a therapeutic endoscopic technique that has been developed as an alternative to surgery in adults, but is rarely used in children. There are a few reports on use of gastric ESD in children[7-9]. Further, there are a couple of reports showing that ESD is useful for treating anorectal tumors close to the dentate line[10,11]. This procedure is an attractive option for en bloc resection of large sessile or flat colorectal lesions and is associated with very low recurrence rates. However, the need for advanced technical skills, the long operating time, and the higher perforation rate are major disadvantages of ESD. The Japanese Colorectal ESD Standardization Implementation Working Group recommends the following indications for colorectal ESD: large lesions (> 20 mm) suspicious for high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or early cancer, lesions that display fibrosis including sporadic adenomas in chronic inflammation or residual carcinoma after previous endoscopic therapy[12]. Patel et al[13] reviewed the outcomes of colorectal ESD and found that it results in en bloc resection, complete resection, and recurrence rates of 89%, 76%, and 1%, respectively.

In our case the polyp measured 10 mm in diameter, so we initially planned to remove it by EMR, but subsequently selected ESD because the location of the lesion made en bloc resection difficult. The polyp was resected successfully, and the patient did not experience any complications after the procedure. However, the safety of this method in pediatric patients requires further study.

According to the US and European guidelines for the management of colorectal polyps, post-polypectomy follow-up examinations should be performed once every three years in cases involving TSA ≥ 10 mm in diameter. However, the risk of pediatric serrated lesions progressing to cancer remains unclear. In the present case, we will need to perform yearly surveillance colonoscopy. It will also be necessary to carry out surveillance colonoscopy in the patient’s family members.

In conclusion, TSA can occur in children, and ESD is a useful treatment for the lesion. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a pediatric TSA that was resected by ESD. Clinicians should be aware of the precancerous potential of pediatric TSA.

A 12-year-old boy with a 4-month history of hematochezia but no other symptoms.

Physical examination at admission was unremarkable.

Juvenile polyps, hemorrhoids, colonic malignancy, etc.

Initial laboratory data were within normal limits.

Colonoscopy revealed an elevated polypoid lesion measuring 10 mm in diameter in the lower rectum.

Histopathological examination revealed a traditional serrated adenoma (TSA).

The patient was successfully treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

There is no report of pediatric TSA prior to this case. Further, this is the first pediatric TSA resected using ESD.

TSA is an uncommon type of serrated adenoma and sometimes difficult to separate from other serrated polyps and conventional adenomas. Further, TSA can be a precancerous lesion.

TSA can occur in children, and ESD is a useful treatment for the condition.

The authors presented a rare case of ESD for pediatric traditional serrated adenoma. This experience is interesting.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Imaeda H, Oka S S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Thakkar K, Alsarraj A, Fong E, Holub JL, Gilger MA, El Serag HB. Prevalence of colorectal polyps in pediatric colonoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1050-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gupta SK, Fitzgerald JF, Croffie JM, Chong SK, Pfefferkorn MC, Davis MM, Faught PR. Experience with juvenile polyps in North American children: the need for pancolonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1695-1697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Latt TT, Nicholl R, Domizio P, Walker-Smith JA, Williams CB. Rectal bleeding and polyps. Arch Dis Child. 1993;69:144-147. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Cynamon HA, Milov DE, Andres JM. Diagnosis and management of colonic polyps in children. J Pediatr. 1989;114:593-596. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Poddar U, Thapa BR, Vaiphei K, Singh K. Colonic polyps: experience of 236 Indian children. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:619-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Saito S, Tajiri H, Ikegami M. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum: Endoscopic features including image enhanced endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:860-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wall J, Esquivel M, Bruzoni M, Wright R, Berquist W, Albanese C. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection of a Large Hamartoma in a Young Child. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:e5-e7. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Jung EY, Choi SO, Cho KB, Kim ES, Park KS, Hwang JB. Successful endoscopic submucosal dissection of a giant polyp in a 21-month-old female. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:323-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Otake K, Uchida K, Inoue M, Matsushita K, Hashimoto K, Toiyama Y, Tanaka K, Nakatani K, Kawai K, Kusunoki M. A large, solitary, semipedunculated gastric polyp in pediatric juvenile polyposis syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1313-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tamaru Y, Oka S, Tanaka S, Hiraga Y, Kunihiro M, Nagata S, Furudoi A, Ninomiya Y, Asayama N, Shigita K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for anorectal tumor with hemorrhoids close to the dentate line: a multicenter study of Hiroshima GI Endoscopy Study Group. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4425-4431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Imai K, Hotta K, Yamaguchi Y, Shinohara T, Ooka S, Shinoki K, Kakushima N, Tanaka M, Takizawa K, Matsubayashi H. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic submucosal dissection of rectal tumors extending to the dentate line. Endoscopy. 2015;47:529-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tanaka S, Terasaki M, Hayashi N, Oka S, Chayama K. Warning for unprincipled colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: accurate diagnosis and reasonable treatment strategy. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:107-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Patel N, Patel K, Ashrafian H, Athanasiou T, Darzi A, Teare J. Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: Systematic review of mid-term clinical outcomes. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:405-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |