Published online Jun 28, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i24.4428

Peer-review started: December 20, 2016

First decision: January 19, 2017

Revised: February 23, 2017

Accepted: June 1, 2017

Article in press: June 1, 2017

Published online: June 28, 2017

Processing time: 188 Days and 23.6 Hours

To use a national database of United States hospitals to evaluate the incidence and costs of hospital admissions associated with gastroparesis.

We analyzed the National Inpatient Sample Database (NIS) for all patients in whom gastroparesis (ICD-9 code: 536.3) was the principal discharge diagnosis during the period, 1997-2013. The NIS is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient care database in the United States. It contains data from approximately eight million hospital stays each year. The statistical significance of the difference in the number of hospital discharges, length of stay and hospital costs over the study period was determined by regression analysis.

In 1997, there were 3978 admissions with a principal discharge diagnosis of gastroparesis as compared to 16460 in 2013 (P < 0.01). The mean length of stay for gastroparesis decreased by 20 % between 1997 and 2013 from 6.4 d to 5.1 d (P < 0.001). However, during this period the mean hospital charges increased significantly by 159 % from $13350 (after inflation adjustment) per patient in 1997 to $34585 per patient in 2013 (P < 0.001). The aggregate charges (i.e., “national bill”) for gastroparesis increased exponentially by 1026 % from $50456642 ± 4662620 in 1997 to $568417666 ± 22374060 in 2013 (P < 0.001). The percentage of national bill for gastroparesis discharges (national bill for gastroparesis/total national bill) has also increased over the last 16 years (0.0013% in 1997 vs 0.004% in 2013). During the study period, women had a higher frequency of gastroparesis discharges when compared to men (1.39/10000 vs 0.9/10000 in 1997 and 5.8/10000 vs 3/10000 in 2013). There was a 6-fold increase in the discharge diagnosis of gastroparesis amongst type 1 DM and 3.7-fold increase amongst type 2 DM patients over the study period (P < 0.001).

The number of inpatient admissions for gastroparesis and associated costs have increased significantly over the last 16 years. Inpatient costs associated with gastroparesis contribute significantly to the national healthcare bill. Further research on cost-effective evaluation and management of gastroparesis is required.

Core tip: Gastroparesis is a debilitating condition which ranges in severity from minimal to severe symptoms requiring prolonged hospitalization and interventions. There is limited data on rates and costs associated with gastroparesis admissions. Our study found 4-fold increase in gastroparesis discharges over the study period and significant increases in gastroparesis discharges related to diabetes type 1 and type 2.

- Citation: Wadhwa V, Mehta D, Jobanputra Y, Lopez R, Thota PN, Sanaka MR. Healthcare utilization and costs associated with gastroparesis. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(24): 4428-4436

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i24/4428.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i24.4428

Gastroparesis is a syndrome due to delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction. Cardinal symptoms include early satiety, postprandial fullness, nausea, vomiting, bloating, and upper abdominal pain[1]. It is a debilitating condition which ranges in severity from minimal to severe symptoms requiring prolonged hospitalization and intervention[2]. Gastroparesis can significantly affect the quality of life in affected individuals[3,4]. Two most common etiologies associated with gastroparesis is Diabetes Mellitus and “Idiopathic causes”[5].

There have been only two epidemiological studies on gastroparesis so far, and both of those studies relied on data collected from the patients who came to the hospital to seek medical attention rather than a random sample of the people in the community. One of these studies from Olmsted County in Minnesota showed age adjusted prevalence of gastroparesis to be 9.6 per 100000 people in men and 37.8 per 100000 people in women with a 1:4 ratio[6].

To our knowledge, there has been only one study in 2008, which reported on the increasing hospitalizations for gastroparesis and the economic impact on health care in the United States, and it assessed trends from 1995 to 2004[2].

Although previous studies have reported on the health care costs associated with gastroparesis, there is no reported study in recent years. Given the limited data and rising hospitalizations for gastroparesis and related complications, the aim of our study was to assess the incidence and healthcare costs incurred from hospital admissions related to gastroparesis in the United States.

To obtain a population based estimate of national trends, we used the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database. The NIS is part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. It is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient care database in the United States and was designed to approximate a 20% sample of United States nonfederal hospitals and is stratified according to geographic region, ownership, location, teaching status and bed size till 2011. In 2013, NIS was redesigned to approximate a 20-percent stratified sample of discharges from United States community hospitals of all the participating states, excluding rehabilitation and long-term acute care hospitals. The NIS contains data from approximately 8 million hospital stays each year. The 1997 NIS is drawn from 22 States and contains information on all inpatient stays from over 1000 hospitals, totaling about 7.1 million records. The 2013 NIS contains discharge data from over 4000 hospitals in 44 States, totaling about 8 million records. This large database is an excellent representative sample of the general United States population, representing more than 95 percent of the United States population and useful for analyzing health care utilization, access, charges, quality, and outcomes[7,8]. The NIS database provides only administrative data for analysis. Patient specific clinical data (i.e., laboratory tests, procedures) are not available[9].

To identify the cases of gastroparesis, we queried the NIS database in order to recover hospital data on all discharge diagnoses with a primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis code of 536.3 (Gastroparesis). The query parameters were configured for the period 1997-2013. NIS data is available from 1988 to 2013, however, in 1997, there was a change in the NIS dataset to include details of the patient and hospital characteristics allowing in-depth analysis of trends over time. Therefore, we chose this particular period for our study.

In our study, we assume for the purpose of analysis, that all patient had diagnosis of gastroparesis. According to the HCUP net, principal diagnosis is defined as “the condition established after study to be chiefly responsible for occasioning the admission of the patient to the hospital for care. The principal diagnosis is always the reason for admission” [Definition according to the Uniform Bill (UB-92)]. Given that these patients were hospitalized, they are likely to have undergone additional testing to exclude organic disease, thereby making the gastroparesis diagnosis more accurate.

Patient demographics recorded included age and gender. Hospital characteristics recorded were location (northeast, midwest, south and west) (metropolitan vs non-metropolitan area), type (teaching vs non-teaching) and size (small, medium, and large). As per the HCUPnet definitions, metropolitan areas are the ones with population of at least 50000 people. Areas with population less than that are the non-metropolitan areas. A hospital is considered to be a teaching hospital if the American Hospital Association Annual Survey indicates it has an AMA-approved residency program, is a member of the Council of Teaching Hospitals, or has a ratio of full-time equivalent interns and residents to beds of 0.25 or higher. The definition of bed size varied according to the hospital location and teaching status. The range for small hospitals was from 1 to 299 beds. The bed size range for medium hospitals was from 50 to 499 and the bed size range for large hospitals was from 100 to 500 and more. We also looked at the payer status for all admissions. “Hospital charges” is defined as the amount the hospital charged for the entire hospital stay. It does not include professional (MD) fees. “Aggregate charges” or the "national bill" is defined as the sum of all charges for all hospital stays in the United States “Length of stay” is defined as the number of nights the patient remained in the hospital for this stay.

The trends for the annual point estimates of the frequency of gastroparesis for the data sample were plotted and analyzed. The annual frequency of discharges with gastroparesis was computed by dividing the annual number of discharges with gastroparesis listed in the NIS database in a given year by the total number of all discharges listed in the NIS for the same year.

The temporal trend in frequencies of discharges, length of stay, hospital charges and frequencies of deaths in subjects with gastroparesis was assessed by linear and polynomial regression. The most appropriate functional form for the trend was assessed by examination of regression diagnostic plots. Linear shape was determined for hospital charges and in-hospital deaths; a quadratic shape for length of stay and a cubic shape for number of discharges and discharge rate. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, The SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

In addition to the percentages available adjacent to the data in the tables, the frequency per 10000 admissions for each categorical variable was also calculated. These numbers represent the density of patients diagnosed with gastroparesis compared with the total number of hospital discharges per category. Each frequency was calculated by dividing the number of patients with gastroparesis by the total discharges in a specific categorical variable for each year and multiplying the number by 10000. We view the counts as arising from a Poisson distribution and the total discharges as an off set, yielding Poisson rates that have been compared over time using Poisson regression, which yields relative rates that express the ratio of rate per 10000 in 2013 to that in 1997. These values differ from the percentages, which describe each category exclusively for either patients with gastroparesis or for total discharges.

The percentages distinguished differences among the variables for each specific year, whereas the frequencies were vital in comparing trends from 1997 to 2013, especially for age group and region.

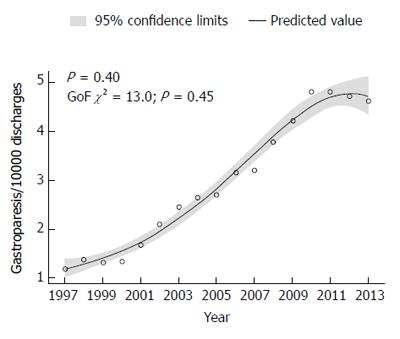

Over our study period, the total number of hospital discharges with a principal discharge diagnosis of gastroparesis increased by 313.7% from 3978 to 16460 (P < 0.001). During the same period, the number of hospital discharges with gastroparesis as a principal or a secondary diagnosis increased from 86996 to 245495 (P < 0.001). Discharges due to gastroparesis were stable in the late 90’s then had a steady increase and seem to be stabilizing over the last few years; this followed a cubic shape (Figure 1).

The frequency of hospital discharges for gastroparesis as a principal diagnosis increased about 4-folds from 1.2/10000 discharges to 4.6/10000 discharges [RR = 3.86 (3.7-3.99), P < 0.001; Table 1].

| Factor | 1997 | 2013 | ||||

| Total | Gastroparesis | Gastroparesis per 10000 discharges | Total | Gastroparesis | Gastroparesis per 10000 discharges | |

| Total discharges, n | 33232257 | 3978 | 1.2 | 35597792 | 16460 | 4.62 |

| Age (yr), mean ± SE | 46.9 ± 0.37 | 53.1 ± 0.93 | - | 48.7 ± 0.20 | 46.5 ± 0.40 | - |

| Age (yr) | ||||||

| < 1 | 4272022 (12.9) | 4 (0.11) | 0.01 | 4232808 (11.9) | 55 (0.33) | 0.13 |

| 1-17 | 1766762 (5.3) | 88 (2.2) | 0.5 | 1393028 (3.9) | 735 (4.5) | 5.3 |

| 18-44 | 9074287 (27.3) | 1335 (33.6) | 1.5 | 8727809 (24.5) | 6825 (41.5) | 7.8 |

| 45-64 | 6226757 (18.7) | 1279 (32.1) | 2.1 | 8753270 (24.6) | 5985 (36.4) | 6.8 |

| 65-84 | 9645107 (29.0) | 1109 (27.9) | 1.1 | 9581434 (26.9) | 2530 (15.4) | 2.6 |

| 85+ | 2246309 (6.8) | 164 (4.1) | 0.73 | 2906938 (8.2) | 330 (2.0) | 1.1 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 13635083 (41.0) | 1255 (31.5) | 0.92 | 15154195 (42.6) | 4565 (27.7) | 3 |

| Female | 19594784 (59.0) | 2724 (68.5) | 1.4 | 20436357 (57.4) | 11895 (72.3) | 5.8 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 19121956 (72.8) | 2511 (76.0) | 1.3 | 22044881 (66.1) | 10255 (65.3) | 4.7 |

| Black | 3643618 (13.9) | 542 (16.4) | 1.5 | 4951772 (14.8) | 3455 (22.0) | 7 |

| Hispanic | 2399687 (9.1) | 149 (4.5) | 0.62 | 4079463 (12.2) | 1450 (9.2) | 3.6 |

| Other | 1116457 (4.2) | 104 (3.2) | 0.93 | 2285194 (6.8) | 555 (3.5) | 2.4 |

| Diabetes type I | ||||||

| No | 31704513 (95.4) | 3451 (86.7) | 1.09 | 35230452 (99.0) | 15690 (95.3) | 4.5 |

| Yes | 1527744 (4.6) | 527 (13.3) | 3.4 | 367340 (1.03) | 770 (4.7) | 21 |

| Diabetes type II | ||||||

| No | 30506553 (91.8) | 3561 (89.5) | 1.2 | 28484056 (80.0) | 12430 (75.5) | 4.4 |

| Yes | 2725703 (8.2) | 417 (10.5) | 1.5 | 7113736 (20.0) | 4030 (24.5) | 5.7 |

| Abdominal pain | ||||||

| No | 33090536 (99.6) | 3894 (97.9) | 1.2 | 35272547 (99.1) | 15460 (93.9) | 4.4 |

| Yes | 141721 (0.43) | 85 (2.1) | 6 | 325245 (0.91) | 1000 (6.1) | 30.7 |

| Nausea and vomiting | ||||||

| No | 33023309 (99.4) | 3641 (91.5) | 1.1 | 35111052 (98.6) | 14915 (90.6) | 4.2 |

| Yes | 208948 (0.6) | 338 (8.5) | 16.2 | 486740 (1.4) | 1545 (9.4) | 31.7 |

| PEG tube | ||||||

| No | 33123551 (99.7) | 3907 (98.2) | 1.2 | 35330272 (99.2) | 15805 (96.0) | 4.5 |

| Yes | 108706 (0.33) | 72 (1.8) | 6.6 | 267520 (0.75) | 655 (4.0) | 24.5 |

| CCI, mean ± SE | 2.1 ± 0.02 | 2.2 ± 0.10 | - | 2.5 ± 0.01 | 2.3 ± 0.04 | - |

| CCI | ||||||

| 0-1 | 17337338 (52.2) | 1704 (42.8) | 0.98 | 16487769 (46.3) | 7645 (46.4) | 4.6 |

| 2-3 | 6334834 (19.1) | 1141 (28.7) | 1.8 | 7119525 (20.0) | 4580 (27.8) | 6.4 |

| 4-5 | 6450519 (19.4) | 850 (21.4) | 1.3 | 6656101 (18.7) | 2660 (16.2) | 4 |

| 6-7 | 2260947 (6.8) | 255 (6.4) | 1.1 | 3543623 (10.0) | 1080 (6.6) | 3 |

| 8+ | 848620 (2.6) | 27 (0.69) | 0.32 | 1790774 (5.0) | 495 (3.0) | 2.8 |

| Primary payer | ||||||

| Medicare | 12070472 (36.4) | 1737 (43.8) | 1.4 | 13986550 (39.4) | 6290 (38.2) | 4.5 |

| Medicaid | 5449545 (16.4) | 422 (10.6) | 0.77 | 7417129 (20.9) | 3405 (20.7) | 4.6 |

| Private Insurance | 12814962 (38.7) | 1471 (37.1) | 1.1 | 10851650 (30.5) | 5215 (31.7) | 4.8 |

| Other | 2817077 (8.5) | 334 (8.4) | 1.2 | 3287333 (9.2) | 1540 (9.4) | 4.7 |

| Median household income (quartile) | ||||||

| 1 | 10702405 (34.1) | 1374 (37.1) | 1.3 | 10199933 (29.3) | 5165 (31.9) | 5.1 |

| 2 | 6426395 (20.5) | 703 (19.0) | 1.09 | 9174852 (26.4) | 4255 (26.3) | 4.6 |

| 3 | 4764143 (15.2) | 557 (15.1) | 1.2 | 8400391 (24.1) | 3755 (23.2) | 4.5 |

| 4 | 9469814 (30.2) | 1068 (28.8) | 1.1 | 7023922 (20.2) | 3015 (18.6) | 4.3 |

| Inflation-adjusted costs (2013 $), mean ± SE | 8248.8 ± 156.8 | 9198.2 ± 570.9 | 39513.3 ± 480.5 | 34585.3 ± 895.6 | ||

| Hospital region | ||||||

| Northeast | 6784680 (20.4) | 683 (17.2) | 1.01 | 6730965 (18.9) | 2730 (16.6) | 4.1 |

| Midwest | 7740558 (23.3) | 712 (17.9) | 0.92 | 8004912 (22.5) | 3245 (19.7) | 4.1 |

| South | 12373654 (37.2) | 2028 (51.0) | 1.6 | 13818031 (38.8) | 7940 (48.2) | 5.7 |

| West | 6333365 (19.1) | 554 (13.9) | 0.87 | 7043884 (19.8) | 2545 (15.5) | 3.6 |

| Hospital bed size | ||||||

| Small | 5284821 (16.0) | 480 (12.2) | 0.91 | 4884892 (13.7) | 1980 (12.0) | 4.1 |

| Medium | 11048191 (33.4) | 1328 (33.6) | 1.2 | 9512936 (26.7) | 4790 (29.1) | 5 |

| Large | 16765043 (50.7) | 2144 (54.2) | 1.3 | 21199964 (59.6) | 9690 (58.9) | 4.6 |

| Hospital location | ||||||

| Rural | 5165800 (15.6) | 655 (16.6) | 1.3 | 3954149 (11.1) | 1355 (8.2) | 3.4 |

| Urban | 27932254 (84.4) | 3297 (83.4) | 1.2 | 31643643 (88.9) | 15105 (91.8) | 4.8 |

| Hospital teaching status | ||||||

| Non-teaching hospital | 20931033 (63.2) | 2675 (67.7) | 1.3 | 17188858 (48.3) | 7150 (43.4) | 4.2 |

| Teaching hospital | 12167021 (36.8) | 1278 (32.3) | 1.05 | 18408934 (51.7) | 9310 (56.6) | 5.1 |

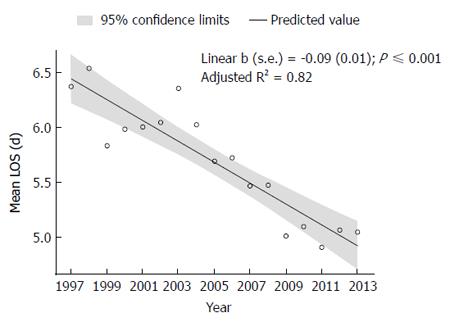

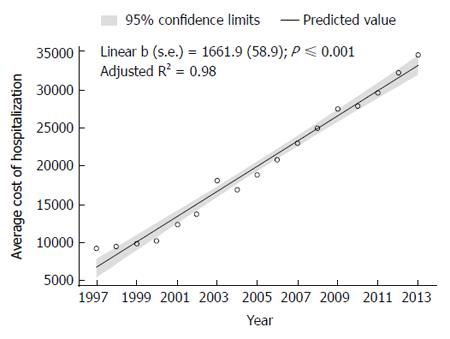

The mean length of stay decreased by about 20% between 1997 and 2013, from 6.4 d to 5.1 d which was statistically significant (P < 0.01). There was a sharp decrease in length of stay around 2004; this trend followed a quadratic shape (Figure 2). Mean hospital charges per patient increased by 159% from $13350 in 1997 to $34585 in 2013, with a mean increase of $1327 per year after adjusting for inflation (P < 0.001; Figure 3).

The aggregate charges (national bill) of hospital visits for gastroparesis (primary diagnosis) increased by 1026 % from $50456642 in 1997 to $568417666 in 2013 (P < 0.001). The percent of the national bill utilization (total aggregate charges for gastroparesis/total national bill) for gastroparesis discharges increased from 0.00013% in 1997 to 0.0004% in 2013. Irrespective of the decrease in the average length of stay, the mean total charges for gastroparesis-related hospital admissions saw a substantial increase between 1997 and 2013.

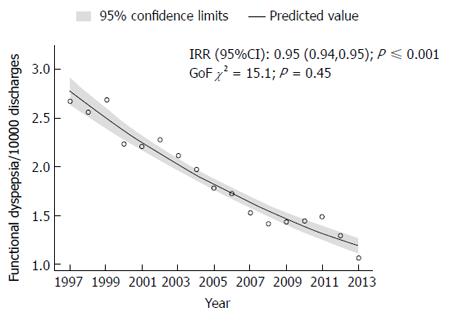

Also, of note, we found that there has been a significant decrease in the hospitalization related to functional dyspepsia from 1997 to 2013, (P < 0.001; Figure 4).

The 45 to 64-year-old age group had the highest rate of relative discharges (e.g., number of patients discharged with primary diagnosis of gastroparesis in 1-17/total number of discharges in the same age group) for gastroparesis in 1997, however we observed a left shift in the trend with highest rate of relative discharge in younger age group of 18-44 in 2013 followed by the above age group (Table 1). We calculated the percent distribution for gastroparesis in each group to the total discharges in that specific age group for 1997 and 2013. The percent distribution increased ten folds for age groups of 1-17 and 5 folds in age group 18-44 (P < 0.001), at least three fold in age group 45-64 (P < 0.001) and more than 2 folds in 65-84 (P < 0.001). Though relative discharge rates have not changed, the absolute number of discharges were highest in age group 18-44 followed by 45-64, in both years.

The frequency of gastroparesis was greatest in women in both 1997 and 2013, increasing from 1.39/10000 discharges in 1997 to 5.8/10000 discharges in 2013 [RR = 4.1 (4.01-4.36), P < 0.001]. Similar trend of increment was also noted in men with an increase from 0.92/10,000 discharges in 1997 to 3/10000 discharges in 2013 [RR = 3.27 (3.07-3.48), P < 0.001].

Amongst the three major races, highest number of gastroparesis related discharges was seen in black race in year, 1997 and 2013. There was a 4.5-fold increase in discharge rate in black race during the study period [RR = 4.68 (4.2-5.1), P < 0.0001]. However, there was a 5.5-fold increase in gastroparesis as a discharge diagnosis in Hispanics from 0.62/10000 cases in 1997 to 3.62/10000 in 2013 [RR = 5.72 (4.8-6.8), P < 0.0001]. White race had 3-fold increase in gastroparesis discharges in 17 years [RR = 3.54 (3.3-3.69), P < 0.0001)].

The relative frequency of gastroparesis discharges has increased for across all forms of payers over the 17-year span. Medicare had the top frequency of gastroparesis discharges, with 1.43 /10000 discharges in 1997 whereas in 2013, the frequency of discharges for Medicare was 4.5/10000 discharges which was the lowest compared with all other forms of payment [RR = 3.12 (2.9-3.2), P < 0.0001] (Table 1). Medicaid had the lowest frequency of discharges in 1997 at 0.77/10000 patient which increased to discharge rate of 4.6/10000 in 2013. [RR = 5.92 (5.3-6.5), P < 0.0001]. This form of payment increased by more than 6 folds followed by private insurance which increased by 4 folds (1.1/10000 in 1997, 4.8/10000 in 2013) [RR = 4.18 (3.9-4.4), P < 0.0001].

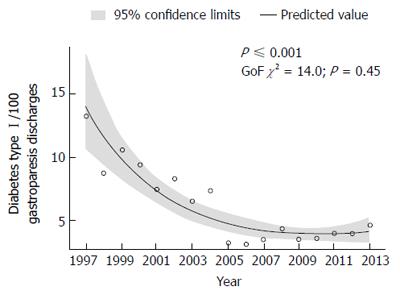

We assessed certain co-morbidities and their association with our discharge diagnosis. Amongst the patient admitted with type 1 DM, discharge diagnosis of gastroparesis was made in 3.4 cases/10000 discharges in 1997 which significantly rose to 21/10000 discharges in 2013 [RR = 6 (5.4-6.7), P < 0.001)]. However, the rate of DM1 among hospitalization with gastroparesis showed a decline from 13.2/100 gastroparesis discharges in 1997 to 4.7/100 discharges in 2013 (P < 0.01) (Figure 5).

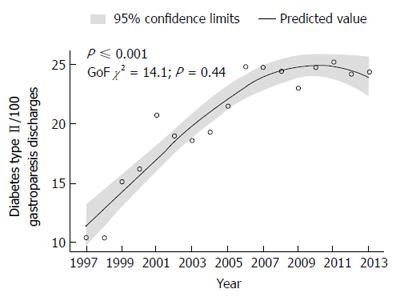

Similarly, amongst patient with diabetes type 2, there was an increase in discharge diagnosis of gastroparesis from 1.5/10000 in 1997 to 5.7/10000 in 2013. [RR = 3.7 (3.3-4.09), P < 0.001]. Interestingly, the rate of DM2 among hospitalization with gastroparesis showed an increase from 10.5/100 gastroparesis discharges in 1997 to 24.5/100 discharges in 2013 (P < 0.01) (Figure 6).

Of all the patients, admitted with abdominal pain. There was a 5-fold increase in the discharge diagnosis of gastroparesis in patients admitted with abdominal pain from 6/10000 cases to 30.7/10000 cases [RR = 5.1 (4.09-6.3), P < 0.001].

Similarly, there was a 2-fold increase in the discharge diagnosis of gastroparesis in patients admitted with nausea/vomiting from 16.2/10000 cases to 31.7/10000 cases [RR = 5.1 (4.09-6.3), P < 0.001)].

There was a 3.5-fold increase in the relative frequency of discharges from 6.6/10000 to 24.5/10000 in the diagnosis of our interest observed over the study period in patients admitted with peg tube [RR = 3.7 (2.89-4.7), P < 0.001)].

Non-metropolitan areas had greater frequency of gastroparesis than metropolitan areas in 1997 (1.3/10000 discharges vs 1.2/10000 discharges in 1997. Interestingly, the frequency of gastroparesis in rural areas increased less rapidly than metropolitan areas in 2013 with a discharge rate of 3.4/10000 [RR = 2.7 (2.4-2.9); P < 0.0001] and 4.8/10000 [RR = 4 (3.89-4.19), P < 0.0001] respectively (Table 1).

The Southern United States, which had the maximum absolute number of both gastroparesis discharges and total discharges, was also found to have the highest relative frequency of gastroparesis discharges when compared to the frequencies of other regions in both 1997 and 2013 (Table 1). The south had the highest frequency of discharges in 1997 with 1.6/10000 discharges, followed by the northeast with 1/10000 discharges, and the Midwest with 0.9/10000 discharges (Table 1). In 2013, the south had the highest frequency of discharges with 5.7/ 10000 discharges, followed by the northeast and the west with 4.1/10000 discharges each (Table 1). The rate of gastroparesis discharges quadrupled for all regions.

The likelihood of patient to be diagnosed with gastroparesis in a teaching hospital (1.05/10000) vs non-teaching hospital (1.3/10000) was similar. However, the trend changed in 2013 with higher likelihood of patient with gastroparesis to be diagnosed in teaching hospital (5.1/10000) vs a non-teaching hospital (4.2/10000) (Table 1).

This study encompasses the number of gastroparesis-related admissions over the last decade. To the best of our knowledge, this is the most updated analysis on trends in gastroparesis related admissions. We used HCUP NIS to estimate the annual number of gastroparesis related hospitalizations which is designed to include approximately 95% of the United States population.

In this study, we have observed a remarkable increase in gastroparesis related admissions in the last 16 years by 300%. This confirms previously reported increase in hospitalization for gastroparesis in previous studies[6,10]. This endemic increase is likely multifactorial; while it may partially be related to the true increase in prevalence, it could be a result of progression of different functional gastrointestinal labels into one term overestimating the true prevalence of Gastroparesis. Decreasing inpatient diagnosis of functional dyspepsia as seen in our study as well as by Nusrat et al[10], clinical diagnosis based on non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms without objective testing resulting in over coding of this diagnosis. Studies have shown that gastric emptying test performed over 4 h increases the rate of detection[11-13]. However, many centers across the country employ shorter duration of test which may lower the sensitivity resulting in more false positive and thus over diagnosis. Over diagnosis rather than a true increase in prevalence can also be explained by regional difference in healthcare and procedure utilization[14]. Opioid analgesics are known to increase gastric emptying time reducing the sensitivity of scintigraphy and may themselves cause nausea and vomiting thus leading to over diagnosis[15]. Such dramatic increase can also be attributed to change in clinical diagnostic criteria with increasing use of gastric emptying tests with reproducible results[12,16,17], increased incidence of diabetes as well as increased longevity of diabetic patients[18]. Also, nutritional support, gastrostomy placement and approval of gastric pacemaker by United States FDA as a treatment modality for refractory gastroparesis may have led to an increase in hospitalizations in the last decade[15,19]. Although the incidence of bariatric surgery has plateaued since 2003, the number of bariatric surgeries being performed in United States remains to be greater than 100000, with gastroparesis being one of its potential complications[20,21].

In our study, we found a decrease in average length of stay from 1997 to 2013. This can be attributed to increased awareness about the disease among clinicians leading to early diagnosis and treatment. One other reason could be the advent of gastric pacemaker therapy, which has been shown to reduce the length of stay. Though there was a decrease in average length of stay, it was found that the cost of each hospitalization has increased considerably, after adjusting for inflation. Nonspecific symptoms at presentation leading to increased utilization of diagnostic modalities are one of the possible reasons for increasing the overall cost of hospitalizations[22]. Advances in diagnostic as well as therapeutic approaches such as GES implantations and surgical interventions also add to overall treatment expenditure.

Very few studies have demonstrated true gender related prevalence of gastroparesis. Jung et al[6] demonstrated a female preponderance of gastroparesis with a female: male age adjusted ratio of 4:1. We used NIS data which reports number of hospitalizations rather than number of incident cases. Hence, it limits our study from estimating the true gender differences in prevalence of the disease. However, the number of hospital discharges were higher among women in both years, consistent with the finding that women are more predisposed to develop this disorder. This increase in rate of hospitalization for women could be because of increased health care seeking behavior by women, as reported previously[22]. Also, functional symptoms and delayed gastric emptying is more commonly seen in women than men[22-25]. One possible hypothesis for this gender disparity, although not clearly demonstrated might be the effect of progesterone on gastric emptying[26,27].

In 2013, of 100 primary inpatient discharge diagnosis made for this disease, 5% had type 1 DM and 25% had type 2 DM bringing the overall etiology of DM to 30% which is consistent with incidence reported in other studies[28]. This also points towards “idiopathic” being the majority of etiology amongst gastroparesis patients.

In our study, we found that the trend shifted leftwards towards younger age group of 18-44 years, in terms of relative frequency of discharges. This could potentially be related to better understanding of disease and increased use of diagnostic modalities, health care accessibility, increase diagnosis of “idiopathic” variant in this age group, early age at diagnosis of diabetes and related complications, increased bariatric surgery among adolescents, and aggressive therapeutic approaches being performed early in the course of the disease. A big proportion of NIS data comes from southern part of United States. With the highest total discharges and the highest number of gastroparesis discharges, Southern United States was found to have the highest number of relative discharges. Beilefeldt et al have hypothesized that this difference could be due to a difference in recognition rather than actual prevalence[14].

This study has several limitations. First and foremost, due to the study design and the nature of the NIS data set being purely administrative, it is dependent on coding practices of each health-care institution. It is more than likely that these results significantly underestimate the actual incidence of gastroparesis discharges, as patients’ discharges may have been erroneously coded with an alternative diagnosis, such as abdominal pain, dyspepsia, gastritis, etc. Secondly, this data set does not control for any errors that may have occurred during data entry. Thirdly, individual patient-specific clinical information, such as laboratory values, medication usage or the procedures performed on the patients were not obtainable, thereby limiting observations on the available demographics of the research sample. Lastly, the NIS data set does not provide adequate patient and hospital specifics to determine the factors that would potentially explain the significant rise in hospital discharges and their costs.

In conclusion, gastroparesis is a growing concern resulting in escalated health care costs and recurrent admissions, demonstrated by significant increase in frequency of gastroparesis related discharges and the healthcare cost burden. Further research on cost effective evaluation and management of gastroparesis is warranted.

Gastroparesis is a digestive disorder due to decreased motility of the stomach resulting in nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dehydration and weight loss. Gastroparesis is now an increasingly common inpatient diagnosis in internal medicine and gastroenterology. There is limited data on the rate and costs associated with inpatient admissions for gastroparesis. The aim of this study was to use a national database of United States hospitals to evaluate the incidence and costs of hospital admissions associated with gastroparesis.

Being female was associated with higher gastroparesis admissions and so was diabetes (type 1 > type 2).

In this study, a large inpatient database was studied which is representative of 95% of the United States population. Data was extracted with all pertinent variables and retrospectively analyzed. Patient specific and hospital specific variables were also investigated.

The patients with gastroparesis getting admitted to the hospital require better management during hospitalization to reduce inpatient length of stay and readmission rate which would reduce burden on healthcare system.

The study is well written with clear message and correct methodology.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Othman MO S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Camilleri M, Bharucha AE, Farrugia G. Epidemiology, mechanisms, and management of diabetic gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:5-12; quiz e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang YR, Fisher RS, Parkman HP. Gastroparesis-related hospitalizations in the United States: trends, characteristics, and outcomes, 1995-2004. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:313-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jaffe JK, Paladugu S, Gaughan JP, Parkman HP. Characteristics of nausea and its effects on quality of life in diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:317-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bielefeldt K, Raza N, Zickmund SL. Different faces of gastroparesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:6052-6060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Soykan I, Sivri B, Sarosiek I, Kiernan B, McCallum RW. Demography, clinical characteristics, psychological and abuse profiles, treatment, and long-term follow-up of patients with gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2398-2404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Jung HK, Choung RS, Locke GR, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Szarka LA, Mullan B, Talley NJ. The incidence, prevalence, and outcomes of patients with gastroparesis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1996 to 2006. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1225-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 474] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sethi S, Wadhwa V, LeClair J, Mikami S, Park R, Jones M, Sethi N, Brown A, Lembo A. In-patient discharge rates for the irritable bowel syndrome - an analysis of national trends in the United States from 1997 to 2010. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1338-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sethi S, Mikami S, Leclair J, Park R, Jones M, Wadhwa V, Sethi N, Cheng V, Friedlander E, Bollom A. Inpatient burden of constipation in the United States: an analysis of national trends in the United States from 1997 to 2010. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:250-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Healthcare cost and utilization project online (internet), Rockville, MD: Agency for healthcare research and quality. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. |

| 10. | Nusrat S, Bielefeldt K. Gastroparesis on the rise: incidence vs awareness? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:16-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abell TL, Camilleri M, Donohoe K, Hasler WL, Lin HC, Maurer AH, McCallum RW, Nowak T, Nusynowitz ML, Parkman HP. Consensus recommendations for gastric emptying scintigraphy: a joint report of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. J Nucl Med Technol. 2008;36:44-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Guo JP, Maurer AH, Fisher RS, Parkman HP. Extending gastric emptying scintigraphy from two to four hours detects more patients with gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:24-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ziessman HA, Bonta DV, Goetze S, Ravich WJ. Experience with a simplified, standardized 4-hour gastric-emptying protocol. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:568-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bielefeldt K. Regional differences in healthcare delivery for gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2789-2798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, Abell TL, Gerson L. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:18-37; quiz 38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 824] [Cited by in RCA: 750] [Article Influence: 62.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Wright RA, Krinsky S. The use of a single gamma camera in radionuclide assessment of gastric emptying. Am J Gastroenterol. 1982;77:890-891. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Collins PJ, Horowitz M, Cook DJ, Harding PE, Shearman DJ. Gastric emptying in normal subjects--a reproducible technique using a single scintillation camera and computer system. Gut. 1983;24:1117-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9344] [Cited by in RCA: 8965] [Article Influence: 426.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Cutts TF, Luo J, Starkebaum W, Rashed H, Abell TL. Is gastric electrical stimulation superior to standard pharmacologic therapy in improving GI symptoms, healthcare resources, and long-term health care benefits? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:35-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Livingston EH. The incidence of bariatric surgery has plateaued in the U.S. Am J Surg. 2010;200:378-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg. 2013;23:427-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1020] [Cited by in RCA: 1004] [Article Influence: 83.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1275-1282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Paternico A, Barbara G, Morselli-Labate AM, Monetti N, Marengo M, Corinaldesi R. Risk indicators of delayed gastric emptying of solids in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1036-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, Melton LJ. Dyspepsia and dyspepsia subgroups: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1259-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 448] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Degen LP, Phillips SF. Variability of gastrointestinal transit in healthy women and men. Gut. 1996;39:299-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wald A, Van Thiel DH, Hoechstetter L, Gavaler JS, Egler KM, Verm R, Scott L, Lester R. Gastrointestinal transit: the effect of the menstrual cycle. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:1497-1500. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Horowitz M, Maddern GJ, Chatterton BE, Collins PJ, Petrucco OM, Seamark R, Shearman DJ. The normal menstrual cycle has no effect on gastric emptying. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;92:743-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hyett B, Martinez FJ, Gill BM, Mehra S, Lembo A, Kelly CP, Leffler DA. Delayed radionucleotide gastric emptying studies predict morbidity in diabetics with symptoms of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:445-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |