Published online Jun 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i23.4285

Peer-review started: January 12, 2017

First decision: March 16, 2017

Revised: April 3, 2017

Accepted: May 9, 2017

Article in press: May 9, 2017

Published online: June 21, 2017

Processing time: 159 Days and 18.6 Hours

To evaluate the imaging course of Crohn’s disease (CD) patients with perianal fistulas on long-term maintenance anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α therapy and identify predictors of deep remission.

All patients with perianal CD treated with anti-TNF-α therapy at our tertiary care center were evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and clinical assessment. Two MR examinations were performed: at initiation of anti-TNF-α treatment and then at least 2 years after. Clinical assessment (remission, response and non-response) was based on Present’s criteria. Rectoscopic patterns, MRI Van Assche score, and MRI fistula activity signs (T2 signal and contrast enhancement) were collected for the two MR examinations. Fistula healing was defined as the absence of T2 hyperintensity and contrast enhancement on MRI. Deep remission was defined as the association of both clinical remission, absence of anal canal ulcers and healing on MRI. Characteristics and imaging patterns of patients with and without deep remission were compared by univariate and multivariate analyses.

Forty-nine consecutive patients (31 females and 18 males) were included. They ranged in age from 14-70 years (mean, 33 years). MRI and clinical assessment were performed after a mean period of exposure to anti-TNF-α therapy of 40 ± 3.7 mo. Clinical remission, response and non-response were observed in 53.1%, 20.4%, and 26.5% of patients, respectively. Deep remission was observed in 32.7% of patients. Among the 26 patients in clinical remission, 10 had persisting inflammation of fistulas on MRI (T2 hyperintensity, n = 7; contrast enhancement, n = 10). Univariate analysis showed that deep remission was associated with the absence of rectal involvement and the absence of switch of anti-TNF-α treatment or surgery requirement. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that only the absence of rectal involvement (OR = 4.6; 95%CI: 1.03-20.5) was associated with deep remission.

Deep remission is achieved in approximately one third of patients on maintenance anti-TNF-α therapy. Absence of rectal involvement is predictive of deep remission.

Core tip: Assessment of perianal fistulas is essential to guide management in Crohn’s disease (CD). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows assessment of morphological and disease activity. Achieving both clinical remission and healing on MRI is a target in the management of perianal CD. In this study, we describe the clinical and radiological evolution of perianal CD in patients on long-term anti-tumor necrosis factor-α treatment. The period of follow-up was two times longer than those in previous studies. Deep remission is possible in one third of patients. Absence of rectal involvement is predictive of deep remission.

- Citation: Thomassin L, Armengol-Debeir L, Charpentier C, Bridoux V, Koning E, Savoye G, Savoye-Collet C. Magnetic resonance imaging may predict deep remission in patients with perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(23): 4285-4292

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i23/4285.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i23.4285

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease, often associated with perianal complications such as fistulas or abscesses[1,2]. Perianal fistulas affect about one-third of patients during the evolution of CD and contribute to impaired quality of life[3]. This disease remains a challenging clinical condition, which is often refractory to conventional therapy. Management is based on combined therapies including antibiotics, drainage surgery, immunosuppressants and anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α therapy[4-11]. Induction therapy with anti-TNF-α drugs allows a complete response after 12 wk in 50% of patients but appears to be of short duration and maintenance therapy is required[8]. Recently, expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells have been proved to be effective as reported by Panés et al[12] in the Lancet.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a highly accurate non-invasive modality for the diagnosis and classification of perianal fistulas; as such it is considered to be the gold standard imaging technique for perianal CD[13-16]. It allows accurate morphological assessment to obtain information on perianal disease activity that can be used for follow-up[17-19]. Improvement in MRI techniques including 3 Tesla imaging and serial MRI examination have emerged as a standard to prepare, to guide and finally to gauge the success of treatment[20]. An MRI-based score (Van Assche) is available and uses different criteria to describe the anatomy (extension) and complexity (active inflammation, abscess) of the fistula[19,21]. Clinically, perianal disease activity in CD is assessed according to fistula drainage[7]. This simple clinical test is effective in defining treatment failure but not in assessing the degree of response, especially when fistula drainage is intermittent. It has been demonstrated that stopping drainage from cutaneous orifices does not necessarily mean that perianal disease has decreased or healed[22,23]. Clinical response often contrasts with the persistence of fistulas on MRI[21,24]. Assessment of fistula activity is challenging and is commonly performed based on T2 hyperintensity[25-27]. T2 weighted sequence with fat suppression is the optimal technique for MRI of fistulas[15]. A gadolinium enhanced T1 weighted sequence is useful for differentiating fluid/pus and granulation tissue[5,26-29]. The definition of fistula healing on MRI is usually based on the disappearance of T2 hyperintense signal and more recently on the absence of gadolinium contrast enhancement[18]. Achieving both clinical remission and healing on MRI is probably the most ambitious target in the management of perianal CD. Healing of lesions can be monitored in luminal CD[30,31].

The aims of this study were to describe the clinical and imaging courses of patients with perianal fistulas on long-term maintenance anti-TNF-α therapy and to identify clinical, endoscopic or imaging features associated with deep remission.

Between 2003 and 2013, all consecutive patients with fistulizing perianal CD treated with maintenance anti-TNF-α therapy at our tertiary care center were evaluated by clinical assessment and two MRI examinations. Patients treated with fibrin glue and plug were excluded. MRI was performed at the initiation of anti-TNF-α treatment and then at least 2 years after. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and informed consent was waived. Patients were diagnosed with CD by either endoscopy and/or histology and had at least one draining perianal fistula. Patients with an abscess had surgical drainage with seton placement, when appropriate, accompanied by a short course of antibiotics (fluoroquinolones and metronidazole). Seton removal was scheduled after completion of anti-TNF-α induction treatment. Immunosuppressant drugs were maintained or started (azathioprine, methotrexate or purinethol). All patients received anti-TNF-α induction treatment either with infliximab (5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2 and 6) or with adalimumab (160, 80, 40 mg at week 0, 2 and 4, respectively). This induction treatment was followed by maintenance therapy based on infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 wk or adalimumab 40 mg every other week. Each treatment could be optimized by increasing the dose or by decreasing the interval between injections. Certozilumab was used in three patients after infliximab or adalimumab failure with an induction treatment of 400 mg at weeks 0, 2 and 4 followed by maintenance therapy (400 mg every 4 wk).

Patients’ characteristics [age, sex, smoking status, family history of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), CD history and activity, duration of disease, localizations of disease according to Montreal criteria, C-reactive protein (CRP) level, albumin rate, and surgical treatment] and rectal involvement at endoscopy were assessed.

All patients were evaluated by MRI before starting anti-TNF-α therapy and at least 2 years after treatment induction.

MRI examination was performed on a Philips Achieva 1.5 Tesla (Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) using a torso phased-array coil. Patients did not receive any bowel preparation. All patients were placed in a supine position, with the pelvis centered on the coil. T2-weighted two-dimensional (2D) turbo spin-echo (TSE) sequences (TR = 6000 ms, TE = 500 ms, scan time = 5 min, matrix of 312 × 512, field of view 250 mm) and T2-weighted 2D TSE sequences with spectral presaturation inversion recovery (SPIR) (TR = 2000 ms, TE = 50 ms, scan time = 5 min, matrix of 312 × 512, field of view 250 mm) were obtained. T1-weighted 2D TSE sequences with and without fat suppression with SPIR (TR = 500 ms, TE = 10 ms, scan time = 5 min, matrix of 285 × 384, field of view = 250 mm) sequences were performed after gadolinium enhancement after checking for normal renal function. The intravenous injection was a mean dose of 15-20 mL gadolinium-DTPA (Magnevist, Schering, Germany) and the scan delay was 60 s. T2-weighted imaging was performed in transverse, sagittal and coronal planes. T1-weighted imaging was performed in transverse and coronal planes. Coronal and transverse planes were angled exactly parallel and perpendicular to the long axis of the anal canal.

The MRI images were assessed by two experienced gastrointestinal radiologists blinded to information on clinical outcome (CSC, EK). The same standardized report was used for initial and follow-up MR examinations. The items studied and their attributed values according to Van Assche were as follows: complexity of the fistula tracks (single unbranched = 1, single branched = 2, multiple = 3); location regarding the sphincters (inter/extra-sphincteric = 1, transsphincteric = 2, suprasphincteric = 3); extension (infralevatoric = 1, supralevatoric = 2); hyperintense appearance in T2-weighted sequences (absent = 0, mild = 4, pronounced = 8); presence of abscesses (hyperintense fluid collections > 3 mm in T2-weighted sequences = 4); and rectal wall involvement (thickened rectal wall = 2). In addition to Van Assche scoring, fistula enhancement after gadolinium-DTPA injection was analyzed and recorded as present or absent.

Clinical evaluation: Clinical assessment was performed by senior gastroenterologists specialized in IBD (GS, LAD). All clinical examinations were performed by the same physician dedicated to one patient according to Present's criteria[7]. A second clinical evaluation was performed to assess the clinical response under treatment. Drainage of fistula openings was studied under gentle finger compression and identified as open and actively draining or closed. Clinical remission was defined as the absence of any draining fistulas and the absence of self-reported drainage episodes by the patient at two successive evaluations. Clinical response was defined as a reduction of 50% or more from baseline in the number of draining fistulas at the clinical evaluation, or in case of non-attendance at the clinical evaluation, as any persisting draining fistulas self-reported by the patient. Patients were considered non-responders in all other circumstances. Anal and rectoscopic patterns were collected to assess the presence of ulcers.

MR evaluation: The two MR examinations were compared to determine changes in items of Van Assche's score. Fistula enhancement was also compared in order to determine whether or not there was persistence of enhancement. Healing on MRI was defined as the disappearance of T2 hyperintensity and contrast enhancement after gadolinium injection.

Deep remission: Deep remission was defined as the association of clinical remission and the absence of anal canal ulcers and healing on MRI.

Qualitative data are presented as numbers and percentages and quantitative data as mean and maximal range values. Comparison of patients according to clinical response or MRI response was made by χ2 test for qualitative and by Student’s t test for quantitative variables. A multivariate analysis was carried out using a model of logistic regression for variables with P < 0.15. Results were considered significant when the P-value was < 0.05. BiostaTGV software was used for statistical analyses.

Forty-nine patients (31 females and 18 males) were enrolled in this study. They ranged in age from 14-70 years, with a mean age of 33 years. Initial clinical characteristics of patients are presented in Table 1. Perineal involvement was present at diagnosis of CD in 6 (12%) patients. An ileocolonic location was observed in 22 (44.9%) patients, pure colonic disease in 15 (30.6%) and an isolated ileal location in 4 (8.2%). Extraintestinal manifestations were present in 11 (22.4%) patients. Disease behavior at diagnosis was considered as inflammatory in 34 (69.4%), stricturing in 8 (16.3%) and penetrating in 7 (14.3%). Eleven (22.4%) patients had ileocolonic resection.

| Patients (n = 49) | |

| Age yr (mean; extreme) | 33; 14-70 |

| Sex ratio (men/women) | 0.58 |

| Familial history of IBD | 4 (8.2) |

| Smoking | 21 (42.9) |

| Mean duration of CD (mo) | 72 (0-300) |

| Location | |

| L1 ileal | 4 (8.2) |

| L2 colonic | 15 (30.6) |

| L3 ileocolonic | 22 (44.9) |

| L2 or L3 + L4 upper disease | 8 (16.3) |

| Disease behavior | |

| Inflammatory | 34 (69.4) |

| Structuring | 8 (16.3) |

| Penetrating | 7 (14.3) |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 11 (22.4) |

| Ileocolonic resection | 11 (22.4) |

| Previous perianal surgery | 40 (81.6) |

| CRP (mg/L) | 11.5 (1.6-167) |

| Albumin rate (g/L) | 35.2 (20-49.2) |

At baseline all patients complained of spontaneous drainage episodes. Active drainage of the fistula opening was confirmed by gentle finger compression in all patients. Rectal involvement at endoscopy was observed in 27 patients.

MRI characteristics at inclusion are summarized in Table 2. The average Van Assche score was 13 ± 4. The most common fistula location was inter- or extra-sphincteric (63.3%) and an infralevatoric extension was observed in 87.8% of patients. Nineteen (38.8%) patients (38.8%) had an abscess. Pronounced T2 hyperintensity of fistula tracks was found in 35 (71.4%) patients. All fistulas were enhanced by gadolinium injection.

| Patients (n = 49) | |

| Van Assche score (mean) | 13 |

| Ramified fistula | 13 (26.5) |

| Multiple fistula | 10 (20.4) |

| Inter/extrasphincteric fistula | 31 (63.3) |

| Transsphincteric fistula | 15 (30.6) |

| Suprasphincteric fistula | 3 (6.1) |

| Infralevatoric extension | 43 (87.8) |

| Supralevatoric extension | 6 (12.2) |

| Abscess | 19 (38.8) |

| Rectal involvement | 21 (42.9) |

| T2 hyperintensity | |

| Absent | 3 (6.1) |

| Mild | 11 (22.4) |

| Pronounced | 35 (71.4) |

| Enhancement | 49 (100) |

| Anorecto-vaginal fistula | 7 (14.3) |

Forty-three (87.8%) patients received infliximab with a mean treatment duration of 23 ± 20 mo and a mean number of 13 treatments. Six (12.2%) patients received adalimumab with a mean duration of 21 ± 14 mo. Thirty-one (63.3%) patients had an associated immunosuppressant drug. During the study period, eleven (22.4%) patients had a switch of anti-TNF-α treatment. Twenty-one (42.8%) patients required surgical drainage of their perianal lesions. The average follow-up period was 40 ± 27 mo.

Among the 49 patients, 26 (53.1%) were in clinical remission, 10 (20.4%) in clinical response and 13 (26.5%) were non-responders at the end of follow-up.

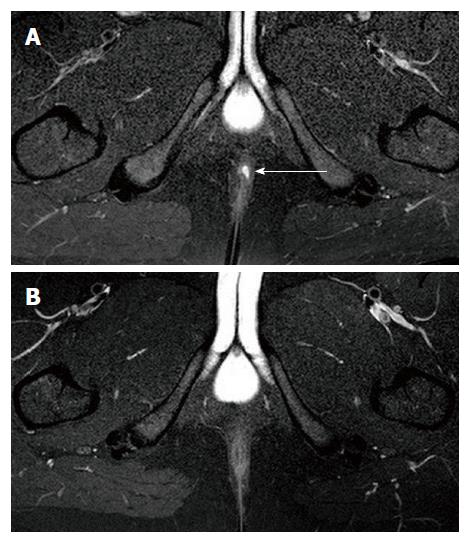

Deep remission (clinical remission, absence of anal canal ulcers and healing on MRI) was observed in 16 (32.7%) patients (Figure 1).

Van Assche score increased in 30 (61.2%) patients and decreased in 11 (22.4%) patients. Average Van Assche score was 8 ± 6. T2 hyperintensity disappeared but contrast enhancement persisted after gadolinium injection in 4 patients. Van Assche score was significantly lower in patients in clinical remission than in non-responders (0 vs 14, P < 0.05). Moreover, the disappearance of both T2 hyperintensity and gadolinium contrast enhancement, between the baseline and final MRI, was significantly more frequent in patients in clinical remission (92.3% vs 26.9% and 100% vs 38.5%, respectively, P < 0.05). No significant change in these patterns was observed in non-responders.

In univariate analysis, clinical remission was significantly associated with male gender (52% vs 20%, P = 0.04), low initial CRP (6 mg/L vs 13 mg/L, P = 0.04), absence of rectal involvement (42.3% vs 69.6%, P = 0.05), absence of ramified fistula at initial MRI (11.5% vs 43.5%, P = 0.02), absence of antibiotics at diagnosis (53.8% vs 87%, P = 0.02), longer duration of treatment with infliximab (32 mo vs 16 mo, P = 0.0004), absence of perianal lesion with infliximab (8.3% vs 63.2%, P = 0.001), and absence of switch of anti-TNF-α treatment (3.8% vs 43.5%, P = 0.001).

In multivariate analysis, two factors were significantly associated with clinical remission: absence of rectal involvement (42.3% vs 69.6%, OR = 4.7, 95%CI: 1.21-49) and absence of switch of anti-TNF-α (3.8% vs 43.5%, OR = 7.7).

In univariate analysis, deep remission was significantly associated with absence of rectal involvement (37.5% vs 63.6%, P = 0.12), absence of surgical drainage at diagnosis (68.8% vs 87.9%, P = 0.011), absence of antibiotics at diagnosis (50% vs 78.8%, P = 0.04), longer duration of treatment with infliximab (27 mo vs 18 mo, P = 0.039), absence of perianal lesion with infliximab (7.1% vs 30.6%, P = 0.008) and absence of switch of anti-TNF-α treatment (0% vs 33.3%, P = 0.009).

In multivariate analysis one factor was significantly associated with deep remission: absence of rectal involvement (37.5% vs 63.6%, OR = 4.6, 95%CI: 1.03-20.5).

In this study, we describe the clinical and radiological evolution of fistulizing perianal CD in a cohort of 49 patients on anti-TNF-α treatment with a mean follow-up period of 40 mo. Of note, the period of follow-up in our study was two times longer than those in previous studies. At the end of follow-up, not only were 53% of our patients in clinical remission but one third was in deep remission, corresponding to clinical remission associated with healing on MRI. One third of patients in clinical remission had a persisting pathology on MRI. In multivariate analysis, there were two predictive factors of clinical remission: absence of rectal involvement at diagnosis and absence of switch of anti-TNF-α during follow-up. Only the absence of rectal involvement remained predictive of deep remission.

The demographic characteristics and clinical remission rates of our patients are comparable to those of other studies[32,33]. The percentage of anorecto-vaginal fistulas in our study (20.4%) was higher than that described in the first study but similar to the most recent ones[34-36]. Our clinical remission rate was slightly higher than those in other studies, probably due to our longer follow-up period and longer duration of anti-TNF-α treatment[8,18,22,23,37]. Additionally, it might also be related to longer seton drainage time as setons were removed after completion of induction treatment. Moreover, 40% of our patients required surgical seton drainage, which is higher than those in previous studies but allowed us to achieve earlier and more efficient drainage before introducing anti-TNF-α treatment[18,21,22]. The treatment regimen we used was comparable to those of previous studies[10].

In our study, deep remission was found in 32.7% of patients. Bell, who reported follow-up in only seven patients, defined improvement as disappearance or reduction of fistulas but there was no analysis of contrast enhancement in MRI[23]. Van Assche, in a series of six patients, reported disappearance of T2 hyperintensity in three patients and absence of fistula in two patients on MRI[21]. Ng found complete healing, defined as absence of T2 hyperintensity of fistula, in 30% of 25 patients at 18 mo[22]. In a previous study from our center, including 20 patients with 1-year follow-up, we reported an improvement in Van Assche score as well as disappearance of T2 hyperintensity and contrast enhancement in 30% of patients[21]. The current study follows this approach with a higher number of patients and longer follow-up and the same MR parameters: T2 hyperintensity used in the Van Assche score and analysis of contrast enhancement. Analysis of contrast enhancement has now clearly proven its interest in follow-up and characterization between inflammatory or fibrotic ileocolonic lesions[31,38]. Recent MRI sequences like diffusion or magnetization transfer could be used in the future for evaluation of patients under treatment[20,39,40]. Compared to our previous study, we found a higher (one third) rate of deep remission at 40 mo than at 12 mo (one quarter)[18]. In univariate analysis, longer duration of treatment and increased rate of healing were significantly associated with deep remission.

Identifying predictive factors for deep remission remains challenging[41]. Tougeron, in a study on 26 patients with infliximab induction therapy, reported that predictive factors significantly associated with clinical remission were low albumin and CD activity index, absence of active luminal disease and absence of endoscopic rectal involvement in univariate analysis; endoscopic rectal involvement was the only factor in multivariate analysis[36]. We confirm the data related to rectal involvement in endoscopy. The presence of proctitis is highly relevant for fistula management and prognosis[15]. In our study, assessment of proctitis by MRI was performed with rectal wall thickness according to Van Assche criteria. Other interesting patterns such as contrast enhancement and MRI features involving the mesorectal tissue like presence of creeping fat have been suggested more recently[42].

The role of MRI in the monitoring of patients on long-term anti-TNF therapy is not well defined. Regular perineal MRI could be useful to assess response to treatment. If unfavorable, optimization or modification of treatment could be proposed. We could consider decreasing or discontinuing treatment in patients in deep remission, but with regular monitoring to detect potential recurrences. Recent data on trough level suggest that monitoring drugs may be useful in making appropriate decisions in this setting[43].

Nonetheless, our study has limitations like absence of perineal disease activity index and trough level monitoring. We did not include patients participating in other therapeutic trials using local therapies like fibrin glue or plug[44-46].

In conclusion, our findings show that deep remission is possible in one third of patients on maintenance anti-TNF-α therapy. Concerning predictive patterns, only absence of rectal involvement is predictive of deep remission. Our results may serve as a basis for future management of anti-TNF-α treatment once deep remission is acquired.

The authors are grateful to Nikki Sabourin-Gibbs, Rouen University Hospital, for her help in editing the manuscript.

Perianal fistulas remain a challenging clinical condition and their management is based on combined therapies. Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α maintenance therapy is often required. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows accurate morphological assessment to obtain information on perianal disease activity that can be used for follow-up.

Anti-TNF-α maintenance therapy is usually required to treat perineal fistulas. MRI examination has emerged to gauge the success of treatment as achieving both clinical remission and healing on MRI is probably the most ambitious target.

In this study, the authors describe the clinical and radiological evolution of perianal Crohn’s disease (CD) in patients on long-term anti-TNF-α treatment. The period of follow-up was two times longer than those in previous studies.

Regular perineal MRI could be useful to assess response to treatment. In case of unfavourable outcome, optimization or modification of treatment could be proposed and in patients in deep remission de-escalation could be considered.

This study described the clinical and radiological evolution of fistulizing perianal CD in a cohort of 49 patients who were treated with anti-TNF-α agents for 40 mo. Authors concluded that deep remission was achieved in approximately one third of patients who were administered with anti-TNF-α therapy and the absence of rectal involvement was predictive of deep remission. However, one third of clinical remission patients had a persisting pathology on MRI. This study is of clinical value to patients with perianal CD.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: France

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Cao GW, Kaimakliotis P, Wasserberg N S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Chouraki V, Savoye G, Dauchet L, Vernier-Massouille G, Dupas JL, Merle V, Laberenne JE, Salomez JL, Lerebours E, Turck D. The changing pattern of Crohn’s disease incidence in northern France: a continuing increase in the 10- to 19-year-old age bracket (1988-2007). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1133-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785-1794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1390] [Cited by in RCA: 1561] [Article Influence: 111.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Schwartz DA, Pemberton JH, Sandborn WJ. Diagnosis and treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn disease. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:906-918. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, van der Woude CJ, Sturm A, De Vos M, Guslandi M, Oldenburg B, Dotan I, Marteau P. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Special situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:63-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 569] [Cited by in RCA: 547] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rutgeerts P. Review article: treatment of perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 4:106-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schwartz DA, Herdman CR. Review article: The medical treatment of Crohn’s perianal fistulas. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:953-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogezand RA, Podolsky DK, Sands BE, Braakman T, DeWoody KL. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1969] [Cited by in RCA: 1839] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Kamm MA, Korzenik JR, Lashner BA, Onken JE. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1581] [Cited by in RCA: 1553] [Article Influence: 74.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Hanauer SB, Panaccione R, Schreiber S, Byczkowski D, Li J, Kent JD. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:52-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1598] [Cited by in RCA: 1620] [Article Influence: 90.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Colombel JF, Schwartz DA, Sandborn WJ, Kamm MA, D’Haens G, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Panaccione R, Schreiber S, Li J. Adalimumab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2009;58:940-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lichtenstein GR, Yan S, Bala M, Blank M, Sands BE. Infliximab maintenance treatment reduces hospitalizations, surgeries, and procedures in fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:862-869. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, Colombel JF, Reinisch W, Baumgart DC, Dignass A, Nachury M, Ferrante M, Kazemi-Shirazi L. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:1281-1290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 628] [Cited by in RCA: 732] [Article Influence: 81.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Buchanan G, Halligan S, Williams A, Cohen CR, Tarroni D, Phillips RK, Bartram CI. Effect of MRI on clinical outcome of recurrent fistula-in-ano. Lancet. 2002;360:1661-1662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Panes J, Bouhnik Y, Reinisch W, Stoker J, Taylor SA, Baumgart DC, Danese S, Halligan S, Marincek B, Matos C. Imaging techniques for assessment of inflammatory bowel disease: joint ECCO and ESGAR evidence-based consensus guidelines. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:556-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 539] [Cited by in RCA: 478] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gecse KB, Bemelman W, Kamm MA, Stoker J, Khanna R, Ng SC, Panés J, van Assche G, Liu Z, Hart A. A global consensus on the classification, diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment of perianal fistulising Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2014;63:1381-1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gionchetti P, Dignass A, Danese S, Magro Dias FJ, Rogler G, Lakatos PL, Adamina M, Ardizzone S, Buskens CJ, Sebastian S. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 2: Surgical Management and Special Situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:135-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 594] [Cited by in RCA: 531] [Article Influence: 66.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Savoye G, Savoye-Collet C. How deep is remission in perianal Crohn’s disease and do imaging modalities matter? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1445-1446; author reply 1446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Savoye-Collet C, Savoye G, Koning E, Dacher JN, Lerebours E. Fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease: contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging assessment at 1 year on maintenance anti-TNF-alpha therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1751-1758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tozer P, Ng SC, Siddiqui MR, Plamondon S, Burling D, Gupta A, Swatton A, Tripoli S, Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA. Long-term MRI-guided combined anti-TNF-α and thiopurine therapy for Crohn’s perianal fistulas. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1825-1834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sheedy SP, Bruining DH, Dozois EJ, Faubion WA, Fletcher JG. MR Imaging of Perianal Crohn Disease. Radiology. 2017;282:628-645. |

| 21. | Van Assche G, Vanbeckevoort D, Bielen D, Coremans G, Aerden I, Noman M, D’Hoore A, Penninckx F, Marchal G, Cornillie F. Magnetic resonance imaging of the effects of infliximab on perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:332-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ng SC, Plamondon S, Gupta A, Burling D, Swatton A, Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA. Prospective evaluation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy guided by magnetic resonance imaging for Crohn’s perineal fistulas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2973-2986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bell SJ, Halligan S, Windsor AC, Williams AB, Wiesel P, Kamm MA. Response of fistulating Crohn’s disease to infliximab treatment assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:387-393. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Ardizzone S, Maconi G, Colombo E, Manzionna G, Bollani S, Bianchi Porro G. Perianal fistulae following infliximab treatment: clinical and endosonographic outcome. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:91-96. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Tissot O, Bodnar D, Henry L, Dubreuil A, Valette PJ. [Ano-perineal fistula in MRI. Contribution of T2 weighted sequences]. J Radiol. 1996;77:253-260. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Szurowska E, Wypych J, Izycka-Swieszewska E. Perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: MRI diagnosis and surgical planning: MRI in fistulazing perianal Crohn’s disease. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:705-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Halligan S, Stoker J. Imaging of fistula in ano. Radiology. 2006;239:18-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Horsthuis K, Lavini C, Bipat S, Stokkers PC, Stoker J. Perianal Crohn disease: evaluation of dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging as an indicator of disease activity. Radiology. 2009;251:380-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Horsthuis K, Ziech ML, Bipat S, Spijkerboer AM, de Bruine-Dobben AC, Hommes DW, Stoker J. Evaluation of an MRI-based score of disease activity in perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Clin Imaging. 2011;35:360-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ordás I, Rimola J, Rodríguez S, Paredes JM, Martínez-Pérez MJ, Blanc E, Arévalo JA, Aduna M, Andreu M, Radosevic A. Accuracy of magnetic resonance enterography in assessing response to therapy and mucosal healing in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:374-382.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Rimola J, Planell N, Rodríguez S, Delgado S, Ordás I, Ramírez-Morros A, Ayuso C, Aceituno M, Ricart E, Jauregui-Amezaga A. Characterization of inflammation and fibrosis in Crohn’s disease lesions by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:432-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sandborn WJ, Fazio VW, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1508-1530. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Bouguen G, Siproudhis L, Bretagne JF, Bigard MA, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Nonfistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease: clinical features, epidemiology, and treatment. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1431-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Singh B, McC Mortensen NJ, Jewell DP, George B. Perianal Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 2004;91:801-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Radcliffe AG, Ritchie JK, Hawley PR, Lennard-Jones JE, Northover JM. Anovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:94-99. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Tougeron D, Savoye G, Savoye-Collet C, Koning E, Michot F, Lerebours E. Predicting factors of fistula healing and clinical remission after infliximab-based combined therapy for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1746-1752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Roumeguère P, Bouchard D, Pigot F, Castinel A, Juguet F, Gaye D, Capdepont M, Zerbib F, Laharie D. Combined approach with infliximab, surgery, and methotrexate in severe fistulizing anoperineal Crohn’s disease: results from a prospective study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:69-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Rimola J, Rodriguez S, García-Bosch O, Ordás I, Ayala E, Aceituno M, Pellisé M, Ayuso C, Ricart E, Donoso L. Magnetic resonance for assessment of disease activity and severity in ileocolonic Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2009;58:1113-1120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 508] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Dohan A, Taylor S, Hoeffel C, Barret M, Allez M, Dautry R, Zappa M, Savoye-Collet C, Dray X, Boudiaf M. Diffusion-weighted MRI in Crohn’s disease: Current status and recommendations. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;44:1381-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Pinson C, Dolores M, Cruypeninck Y, Koning E, Dacher JN, Savoye G, Savoye-Collet C. Magnetization transfer ratio for the assessment of perianal fistula activity in Crohn’s disease. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:80-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Louis E, Vernier-Massouille G, Grimaud JC, Bouhnik Y, Laharie D, Dupas JL, Pillant H, Picon L, Veyrac M, Flamant M. 961 Infliximab Discontinuation in Crohn’s Disease Patients in Stable Remission On Combined Therapy with Immunosuppressors: A Prospective Ongoing Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:A146. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 42. | Tutein Nolthenius CJ, Bipat S, Mearadji B, Spijkerboer AM, Ponsioen CY, Montauban van Swijndregt AD, Stoker J. MRI characteristics of proctitis in Crohn’s disease on perianal MRI. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016;41:1918-1930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ungar B, Levy I, Yavne Y, Yavzori M, Picard O, Fudim E, Loebstein R, Chowers Y, Eliakim R, Kopylov U. Optimizing Anti-TNF-α Therapy: Serum Levels of Infliximab and Adalimumab Are Associated With Mucosal Healing in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:550-557.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Senéjoux A, Siproudhis L, Abramowitz L, Munoz-Bongrand N, Desseaux K, Bouguen G, Bourreille A, Dewit O, Stefanescu C, Vernier G. Fistula Plug in Fistulising Ano-Perineal Crohn’s Disease: a Randomised Controlled Trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:141-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Grimaud JC, Munoz-Bongrand N, Siproudhis L, Abramowitz L, Sénéjoux A, Vitton V, Gambiez L, Flourié B, Hébuterne X, Louis E. Fibrin glue is effective healing perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2275-2281, 2281.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A-36A. [PubMed] |