Published online May 21, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i19.3530

Peer-review started: December 29, 2017

First decision: March 3, 2017

Revised: March 14, 2017

Accepted: May 4, 2017

Article in press: May 4, 2017

Published online: May 21, 2017

Processing time: 142 Days and 23.2 Hours

To evaluate the short health scale (SHS), a new, simple, four-part visual analogue scale questionnaire that is designed to assess the impact of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) on health-related quality of life (HRQOL), in Korean-speaking patients with IBD.

The SHS was completed by 256 patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Individual SHS items were correlated with inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ) dimensions and with disease activity to assess validity. Test-retest reliability, responsiveness and patient or disease characteristics with probable association with high SHS scores were analyzed.

Of 256 patients with IBD, 139 (54.3%) had UC and 117 (45.7%) had CD. The correlation coefficients between SHS questions about “symptom burden”, “activities of daily living”, and “disease-related worry” and their corresponding dimensions in the IBDQ ranged from 0.62 to 0.71, compared with correlation coefficients ranging from -0.45 to -0.61 for their non-corresponding dimensions. There was a stepwise increase in SHS scores, with increasing disease activity in both CD and UC (all P values < 0.001). Reliability was confirmed with test-retest correlations ranging from 0.68 to 0.90 (all P values < 0.001). Responsiveness was confirmed with the patients who remained in remission. Their SHS scores remained unchanged, except for the SHS dimension “disease-related worry”. In the multivariate analysis, female sex was associated with worse “general well-being” (OR = 2.28, 95%CI: 1.02-5.08) along with worse disease activity.

The SHS is a valid and reliable measure of HRQOL in Korean-speaking patients with IBD.

Core tip: The short health scale (SHS) is a new, simple, four-part visual analog scale questionnaire that is designed to assess the impact of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) on health-related quality of life (HRQOL). In Korean-speaking IBD patients, total SHS scores correlated with total IBDQ scores in both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). There was a stepwise increase in SHS scores with increasing disease activity in both CD and UC. Reliability was confirmed with test-retest correlations. Thus, SHS is a valid and reliable measure of HRQOL in Korean-speaking patients with IBD.

- Citation: Park SK, Ko BM, Goong HJ, Seo JY, Lee SH, Baek HL, Lee MS, Park DI. Short health scale: A valid measure of health-related quality of life in Korean-speaking patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(19): 3530-3537

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i19/3530.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i19.3530

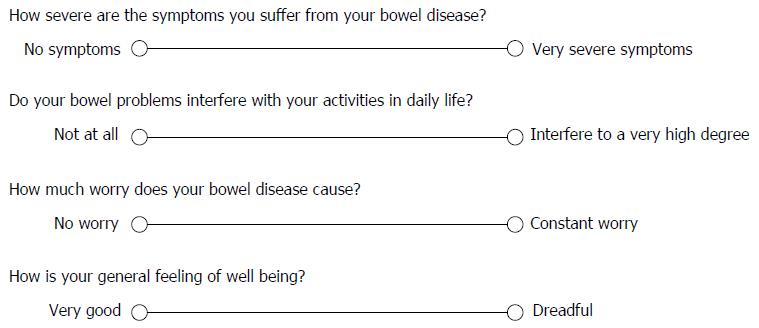

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are the two most common variants of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD); both are chronic relapsing disorders that significantly affect daily life[1,2]. The biological burden of IBD had been measured using disease activity scales such as the Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) in CD[3]. However, these do not reflect the well-being of patients with chronic illness. In contrast, an important patient-reported outcome, the health-related quality of life (HRQOL), refers to the subjective perception of illness and disease impact on daily life and general well-being; the HRQOL is therefore an essential part of health assessment in patients with IBD in both clinical practice and clinical trials[4,5]. Early HRQOL scales for IBD involved extensive questions relating to specific symptoms, social function, limitation of activities, and mental health, and were time-consuming to complete and evaluate[6]. Since then, shorter scales have been developed, such as the short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ)[7], and short health scale (SHS)[8]. The SHS consists of four simple 100-mm visual analog scales assessing factors traditionally associated with HRQOL (symptom burden, activities of daily living, disease related worry, and sense of general well-being). The questions were designed to be open-ended, so that patients could score any or all aspects of their life that they felt were important to them when completing the questionnaire. The SHS was validated in Swedish-speaking[8,9], Norwegian-speaking[10], and English-speaking[11] patients with IBD.

Although the incidence of IBD in Asia has increased rapidly in recent years[12-14], only a few studies have investigated HRQOL in Korean patients with IBD[15]. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the SHS in Korean-speaking patients with IBD.

A total of 272 patients with IBD, who visited the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital and Soonchunhyang University Hospital, Bucheon between March 2016 and August 2016 were invited to participate in this study. Of these, 265 patients agreed (97.4% response rate). After excluding 9 patients whose questionnaires did not have evaluable SHS data, 256 patients were finally enrolled. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, South Korea.

QOL was measured using the SHS. The questionnaire was designed to be self-administered and patients were asked to place a mark on the 10-cm visual analog scale that they thought was appropriate to their condition (Figure 1). Scores were presented for each of four dimensions including symptom burden, social function, disease-related worry, and sense of general well-being; the scores were then added for a total score. One gastroenterologist (SKP) translated the English SHS to Korean. QOL was also determined using the 32-item IBDQ that collects data on four dimensions, including bowel symptoms, social function, emotional function, and systemic symptoms. We used the Korean version of the IBDQ, which has been validated for IBD[15].

Disease activity at the time of questionnaire completion was assessed by consulting physicians without knowledge of the questionnaire results. To assess disease activity, the CDAI was used for CD[3], and the Mayo score for UC[16]. CD in remission was defined as a CDAI < 150, mild disease as 150-220, moderate as 220-450, and severe as > 450. UC in remission was defined as a Mayo score 0-2, mild disease as 3-5, moderate as 6-10, and severe as 11-12.

Validity: We assessed validity by correlating both individual SHS items and total SHS score with IBDQ dimensions and total score. The score for each SHS question should be closely associated with other HRQOL measures reflecting the same dimension of health (convergent validity), whereas the association with variables that measure other health dimensions should be less (discriminant validity). The SHS item “symptom burden” was expected to be closely associated with the IBDQ dimension “bowel symptoms”, the SHS item “social function” with the IBDQ dimension “social function”, the SHS item “disease-related worry” with the IBDQ dimension “emotional function”, and the SHS item “general well-being” with the IBDQ dimension “systemic symptoms” or “emotional function”. We also compared SHS scores according to disease activity, as it can be assumed that disease activity would influence QOL (known-groups comparison/predictive validity).

Reliability: Test-retest reliability was determined from results 2 to 8 wk apart for SHS questions in patients in remission.

Responsiveness: Changes in SHS scores in patients who remained in remission and who experienced a change in disease activity, from remission to mild to moderate activity or vice versa, were measured for responsiveness. To evaluate responsiveness, the patients were offered a second appointment 3-6 mo later, or earlier in the event of deterioration.

Influence of patient or disease characteristics on SHS: Patient or disease characteristics with probable association with high SHS scores were analyzed. High score was defined as ≥ 5 cm for each SHS question.

Continuous data were presented as medians and interquartile ranges and categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Correlations between continuous data were analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rs). For test-retest reliability, total score was analyzed using the Bland-Altman plot. Differences in unpaired and paired groups were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test, respectively. To investigate the influence of patient or disease characteristics on SHS, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed. In the multivariate analysis, variables with probable association with high scores for each of the four SHS dimensions were included. These variables were age (< 40 years, ≥ 40 years), sex (female, male), education (beyond high school, junior school), smoking status (never, previous, or current smoker), family history (yes, no), disease type (CD, UC), disease duration (≥ 5 years, < 5 years), anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) or azathioprine use (yes or no), history of operation (yes or no), and disease activity based on CDAI for CD and Mayo score for UC (remission, mild, moderate, severe). For each variable, the odds ratio (OR) and 95%CI were provided. Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

Demographic and disease characteristics are shown in Table 1. Among 256 patients who were finally enrolled, median age was 37 and 64% were male. Of these, 139 (54.3%) had UC and 117 (45.7%) had CD. The median duration of disease was 4.8 years.

| Variables | UC (n = 139) | CD (n = 117) | P value |

| Age: yr, median (range) | 43 (16-70) | 32 (17-60) | < 0.001 |

| Sex, Male | 83 (59.7) | 81 (69.2) | 0.11 |

| Education1 | 0.04 | ||

| Junior (education to age 16) | 9 (8.5) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Graduate (education to age 19) | 35 (33.0) | 28 (26.9) | |

| Third level education | 62 (58.5) | 74 (71.2) | |

| Family history2 | 11 (10.3) | 4 (3.9) | 0.07 |

| Smoking status3 | 0.25 | ||

| Non-smoker | 64 (60.4) | 64 (63.4) | |

| Ex-smoker | 33 (31.1) | 23 (22.8) | |

| Smoker | 9 (8.5) | 14 (13.9) | |

| Disease duration: years, median (range) | 6.3 (0.1-26.2) | 5.2 (0.1-14.9) | 0.06 |

| Disease location | |||

| Proctitis (UC)/colon (CD) | 39 (28.1) | 27 (23.1) | |

| Left sided (UC)/small bowel (CD) | 47 (33.8) | 27 (23.1) | |

| Pancolitis (UC)/colon+Small bowel (CD) | 53 (38.1) | 63 (53.8) | |

| Disease activity | 0.16 | ||

| Remission | 82 (59.0) | 81/117 (69.2) | |

| Mild | 42 (30.2) | 21/117 (17.9) | |

| Moderate | 14 (10.1) | 14/117 (11.9) | |

| Severe | 1 (0.7) | 1/117 (0.8) | |

| Previous surgery4 | 19 (18.6) | 34 (33.3) | 0.02 |

| Medication | |||

| Azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine | 33 (23.7) | 72 (61.5) | < 0.001 |

| Anti-TNF | 17 (12.2) | 31 (26.7) | 0.003 |

Validity: Table 2 shows correlations between the four SHS dimensions and their corresponding IBDQ items. To establish convergent validity and discriminant validity, each SHS question score should be more closely associated with corresponding than with non-corresponding dimensions of the IBDQ questionnaires. In CD, the correlation coefficients between the SHS questions “symptom burden”, “activities of daily living”, and “disease-related worry” and their corresponding dimensions in the IBDQ ranged from 0.64 to 0.71, compared with correlation coefficients ranging from -0.45 to -0.63 for their non-corresponding dimensions. In UC, correlation coefficients between the SHS questions “symptom burden”, “activities of daily living”, and “disease-related worry” and their corresponding dimensions in the IBDQ were also higher (0.61-0.71) than for their non-corresponding dimensions (0.45-0.59). The remaining SHS question score, “general well-being”, showed closest correlation with the IBDQ score for emotional function, similar to that for the SHS question score for “worry”, with a correlation coefficient of 0.67 for CD and 0.62 for UC.

| Symptoms rs | Activities rs | Worry rs | Well-being rs | Total score rs | |

| Crohn’s disease | |||||

| IBDQ bowel symptoms | -0.66 | -0.54 | -0.45 | -0.52 | |

| IBDQ social function | -0.50 | -0.71 | -0.5 | -0.46 | |

| IBDQ emotional function | -0.49 | -0.59 | -0.64 | -0.67 | |

| IBDQ systemic symptoms | -0.60 | -0.61 | -0.51 | -0.65 | |

| Total score | -0.81 | ||||

| Ulcerative colitis | |||||

| IBDQ bowel symptoms | -0.68 | -0.52 | -0.49 | -0.55 | |

| IBDQ social function | -0.55 | -0.71 | -0.59 | -0.56 | |

| IBDQ emotional function | -0.47 | -0.59 | -0.62 | -0.62 | |

| IBDQ systemic symptoms | -0.45 | -0.56 | -0.50 | -0.52 | |

| Total score | -0.71 |

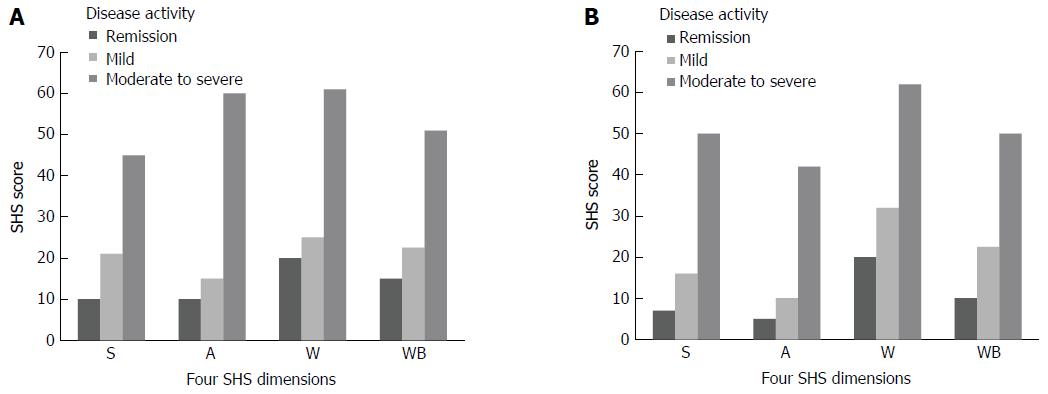

Correlations between the four SHS dimensions and disease activity scores are shown in Figure 2. There was a stepwise increase in all SHS dimensions, with increasing disease activity. For both CD and UC patients in remission, median “disease-related worry” scores were 20 (range 0-100), and were higher than for other dimensions.

Reliability: To assess reliability, test-retest results for 36 patients with IBD (20 with UC, 16 with CD) in remission were investigated. The Spearman rank correlation coefficients for test-retest scores for the SHS questions “symptom burden”, “activities of daily living”, “disease-related worry”, and “general well-being” were 0.70 (P < 0.01), 0.63 (P < 0.01), 0.79 (P < 0.01), and 0.60 (P < 0.01), respectively. The correlation coefficient for the SHS total score was 0.74 (P < 0.01). In the Bland-Altman plot, mean difference was -2.81 (95%CI: -15.55-9.94) (Supplement Figure 1).

Responsiveness: Table 3 shows responsiveness in 88 patients with IBD. Seventy-five patients remained in stable remission and were reexamined after a median 4 mo. Their SHS scores remained unchanged, except for the SHS dimension “disease-related worry”, which decreased during follow-up (17.5-7.5, P < 0.05). A change in disease activity occurred in 21 patients; 15 were in remission at baseline, but changed to mild to moderate disease activity during the follow-up period; 6 patients with mild to moderate activity at baseline repeated the questionnaires when in remission at the median 4-mo follow-up. There was no significant change in scores in the four SHS dimensions between the two test occasions.

| Stable remission (n = 67) | Change in disease activity (n = 21) | |||

| SHS | Remission | Remission | Remission | Mild to moderate |

| Symptoms | 4 (0-35) | 7 (0-50) | 8.5 (5-45) | 15 (2-50) |

| Activities | 3.5 (0-70) | 8 (0-60) | 10 (0-70) | 8.5 (0-60) |

| Worry | 17.5 (0-100) | 7.5 (0-100)a | 20 (7-70) | 27 (7-60) |

| Well-being | 8.5 (0-55) | 6 (0-90) | 17.5 (3-80) | 30 (0-60) |

| Total score | 40 (0-205) | 40 (0-210) | 59 (24-265) | 87 (20-230) |

In the multivariate analysis, disease activity was associated with high scores for each SHS question after adjusting for patient- or disease-related variables (Table 4). In addition, a 3.53-fold increase (95%CI: 1.18-10.56) in the adjusted odds for high score on “activities of daily living” was observed in young patients. In the SHS dimension ‘‘disease-related worry”, the adjusted odds were 4.74 (95%CI: 1.06-21.2), 2.98 (95%CI: 1.43-6.20), and 2.56 (95%CI: 1.06-6.22) among patients with more than high school education, disease duration ≥ 5 years, and anti-TNF use, respectively. Female sex was associated with worse “general well-being” (OR = 2.28, 95%CI: 1.02-5.08) along with worse disease activity.

| Symptoms | Activity | Worry | Well-being | |

| Age < 40 (vs ≥ 40) | 2.76 (0.79-9.56) | 3.53 (1.18-10.56) | 1.06 (0.47-3.28) | 1.67 (0.70-3.94) |

| Sex, Female (vs male) | 0.85 (0.25-2.90) | 3.70 (0.98-7.45) | 1.79 (0.83-3.85) | 2.28 (1.02-5.08) |

| Education, beyond high school (vs junior school) | 0.33 (0.02-5.51) | 1.73 (0.25-11.95) | 4.74 (1.06-21.2) | 1.31 (0.22-7.75) |

| Smoking (vs non or ex-smoking) | 3.79 (0.86-16.43) | 3.43 (0.92-12.77) | 1.02 (0.33-3.16) | 2.78 (0.94-8.21) |

| Family history (vs no) | 0.34 (0.06-1.92) | 1.93 (0.20-18.62) | 0.50 (0.14-1.80) | 0.41 (0.10-1.59) |

| Disease, CD (vs UC) | 0.54 (0.15-1.91) | 0.52 (1.17-1.54) | 0.81 (0.35-1.88) | 1.41 (0.58-3.43) |

| Disease duration ≥ 5 yr (vs < 5 yr) | 1.33 (0.45-3.89) | 2.12 (0.81-5.52) | 2.98 (1.43-6.20) | 1.62 (0.77-3.45) |

| Anti-TNF use (vs no) | 0.81 (0.18-3.59) | 1.69 (0.53-5.44) | 2.56 (1.06-6.22) | 1.01 (0.48-2.68) |

| Azathioprine use (vs no) | 0.55 (0.16-1.91) | 1.39 (0.49-3.94) | 1.39 (0.62-3.08) | 1.69 (0.72-3.96) |

| Bowel operation history (vs no) | 1.19 (0.28-4.94) | 1.80 (0.50-6.47) | 0.91 (0.40-2.06) | 1.09 (0.44-2.68) |

| Disease activity, moderate to severe (vs mild or remission) | 16.6 (4.19-66.18) | 8.02 (2.43-26.43) | 12.56 (3.66-43.09) | 6.03 (1.98-18.40) |

In this study, we verified appropriate psychometric properties for the SHS in Korean patients with IBD, as were previously shown in Western patients with IBD[8-11]. We assessed the SHS for validity, reliability, and responsiveness, and all were confirmed except responsiveness in patients whose disease activity had changed. Associated patient and disease factors such as age, sex, and education were identified in our study.

The SHS is a simple and standardized four-item questionnaire that is traditionally associated with HRQOL[8,9]. It is quick and easy to administer, and our Korean patient population appeared to have little difficulty completing the survey. Validity was confirmed by correlation between the four SHS dimensions and their corresponding IBDQ items. In both CD and UC, the SHS questions for “symptom burden” and “activities of daily living” showed a close association with their corresponding dimensions in the IBDQ, and correlation coefficients were higher than for their non-corresponding dimensions, thus establishing convergent and discriminant validity. Previous studies examined either patient ratings of IBD concerns[8,17] or IBDQ emotional function[11], and both showed high correlations with the SHS “worry” dimension. In this study, we compared the “worry” dimension with IBDQ emotional function and confirmed convergent and discriminant validity. However, for “general well-being”, previous studies examined different dimensions, i.e., either IBDQ emotional function[8] or IBDQ systemic symptoms[11]. In this study, we found close associations between the SHS “well-being” dimension for both IBDQ emotional function and systemic symptoms in CD, and emotional function in UC. This is consistent with results in Swedish-speaking patients[8], and different from those in English-speaking patients[11]. This indicated that well-being is the most comprehensive among various dimensions associated with HRQOL, which is formed by the interaction of biological, psychological, social, and economic variables in patients with IBD. Validity was also supported by the significantly worse scores for all SHS questions in patients with mild to severe disease, compared with those in remission.

The SHS had good reliability, although it was assessed in a small group of patients in remission, using surveys 2 to 6 wk apart. The correlations between the two measurements were high in both CD and UC, and corresponded with the results of previous studies[8-11].

Although patients in stable remission showed no significant change in score, the SHS was not responsive to changes in disease activity. Patients who changed from remission to active disease or vice versa between the two follow-up visits had changes in symptom, worry, well-being, and total scores, but the results did not reach statistical significance, possibly due to the small number of patients. However, patients in stable remission showed no significant change in score, except in the worry dimension. “Disease-related worry” scores were relatively high in patients in remission, compared with scores for other dimensions, and improved after a median 4 mo. It is possible that worry will decrease when a patient is in remission for a certain period of time.

In this study, we also investigated patient and disease factors that might affect QOL. Only a study in Norwegian patients reported factors associated with SHS, and unemployment was adversely associated with SHS social function and general well-being in UC patients[10]. Interestingly, we found that younger age, higher education, and female sex were adversely associated with SHS activity, worry, and well-being dimensions, respectively. In the worry dimension, longer disease duration and anti-TNF use were also adversely associated. As we expected, moderate to severe disease activity was associated with worse scores in all SHS questions, after adjusting for patient- or disease-related variables, especially in the “symptom burden” dimension.

This is the first study to test and validate the SHS in Asian patients. In addition, associated patient and disease factors in the SHS were identified in our study. The open-ended nature of the four SHS questions helps clinicians determine which component of health is affected, and enables decision-making for therapeutic intervention in bowel inflammation or the need for psychological support. The SHS is comprehensive and simple to complete, and can quickly provide information for use in both clinical practice and clinical trials.

Our study had several limitations. First, most subjects were outpatients in remission. Evaluation of a population with a higher proportion of patients with moderate to severe disease is needed. Second, the number of patients who entered the study in remission and subsequently had a relapse during follow-up was small, and limited the confirmation of good responsiveness. Third, only Koreans were included, and further studies of other Asians should be performed to determine SHS reliability as an HRQOL instrument in Asia.

In conclusion, the SHS is a valid and reliable measure of HRQOL in Korean-speaking IBD patients. The SHS can be used in clinical trials and clinical practice to identify the main problems affecting QOL in IBD patients.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Henrik Hjortswang for permission to validate the SHS in Korean.

The short health scale (sHS) was validated in Swedish-speaking, Norwegian-speaking, and English-speaking patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Although the incidence of IBD in Asia has increased rapidly in recent years, only a few studies have investigated health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in Korean patients with IBD. Thus, we evaluate the SHS in Korean-speaking patients with IBD.

An important patient-reported outcome, the HRQOL, refers to the subjective perception of illness and disease impact on daily life and general well-being; the HRQOL is therefore an essential part of health assessment in patients with IBD in both clinical practice and clinical trials.

This is the first study to test and validate the SHS in Asian patients. We verified appropriate psychometric properties for the SHS in Korean patients with IBD, as were previously shown in Western patients with IBD. We assessed the SHS for validity, reliability, and responsiveness, and all were confirmed except responsiveness in patients whose disease activity had changed. Associated patient and disease factors such as age, sex, and education were identified in our study.

The open-ended nature of the four SHS questions helps clinicians determine which component of health is affected, and enables decision-making for therapeutic intervention in bowel inflammation or the need for psychological support. The SHS is comprehensive and simple to complete, and can quickly provide information for use in both clinical practice and clinical trials.

Both the total score for SHS and IBDQ in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis as well as reliability should be also presented as Bland-Altman plot.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Sadik R, Stanciu C S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, Ollendorf DA, Sandler RS, Galanko JA, Finkelstein JA. Direct health care costs of Crohn‘s disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1907-1913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 524] [Cited by in RCA: 532] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Casellas F, López-Vivancos J, Vergara M, Malagelada J. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on health-related quality of life. Dig Dis. 1999;17:208-218. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:439-444. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Garrett JW, Drossman DA. Health status in inflammatory bowel disease. Biological and behavioral considerations. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:90-96. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kappelman MD, Long MD, Martin C, DeWalt DA, Kinneer PM, Chen W, Lewis JD, Sandler RS. Evaluation of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1315-1323.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ, Singer J, Williams N, Goodacre R, Tompkins C. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:804-810. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571-1578. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Hjortswang H, Järnerot G, Curman B, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Tysk C, Blomberg B, Almer S, Ström M. The Short Health Scale: a valid measure of subjective health in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1196-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stjernman H, Grännö C, Järnerot G, Ockander L, Tysk C, Blomberg B, Ström M, Hjortswang H. Short health scale: a valid, reliable, and responsive instrument for subjective health assessment in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:47-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jelsness-Jørgensen LP, Bernklev T, Moum B. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: translation, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change of the Norwegian version of the short health scale (SHS). Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1671-1676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | McDermott E, Keegan D, Byrne K, Doherty GA, Mulcahy HE. The Short Health Scale: a valid and reliable measure of health related quality of life in English speaking inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:616-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ooi CJ, Makharia GK, Hilmi I, Gibson PR, Fock KM, Ahuja V, Ling KL, Lim WC, Thia KT, Wei SC. Asia Pacific Consensus Statements on Crohn’s disease. Part 1: Definition, diagnosis, and epidemiology: (Asia Pacific Crohn’s Disease Consensus--Part 1). J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:45-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang SK, Yun S, Kim JH, Park JY, Kim HY, Kim YH, Chang DK, Kim JS, Song IS, Park JB. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district, Seoul, Korea, 1986-2005: a KASID study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:542-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Puri AS. Epidemiology of Ulcerative Colitis in South Asia. Int Rearch. 2013;11:250-255. |

| 15. | Kim WH, Cho YS, Yoo HM, Park IS, Park EC, Lim JG. Quality of life in Korean patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease and intestinal Behçet’s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1999;14:52-57. [PubMed] |

| 16. | D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Geboes K, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, Lémann M, Marteau P, Rutgeerts P, Schölmerich J. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:763-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 722] [Cited by in RCA: 793] [Article Influence: 44.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li ZM, Mitchell CM, Zagami EA, Patrick DL. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:701-712. [PubMed] |