Published online Feb 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i7.2349

Peer-review started: July 6, 2015

First decision: July 19, 2015

Revised: August 12, 2015

Accepted: November 19, 2015

Article in press: November 19, 2015

Published online: February 21, 2016

Processing time: 220 Days and 17 Hours

AIM: To better understand some of the superficial tiny lesions that are recognized as squamous papilloma of the esophagus (SPE) and receive a different pathological diagnosis.

METHODS: All consecutive patients with esophageal polypoid lesions detected by routine endoscopy at our Endoscopy Centre between October 2009 and June 2014 were retrospectively analysed. We enrolled patients with SPE or other superficial lesions to investigate four key endoscopic appearances (whitish color, exophytic growth, wart-like shape, and surface vessels) and used narrow band imaging (NBI) to distinguish their differences. These series endoscopic images of each patient were retrospectively reviewed by three experienced endoscopists with no prior access to the images. All lesion specimens obtained by forceps biopsy were fixed in formalin and processed for pathological examination. The following data were collected from patient medical records: gender, age, indications for esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and endoscopic characteristics including lesion location, number, color, size, surface morphology, surrounding mucosa, and surface vessels under NBI. Clinicopathological features were also compared.

RESULTS: During the study period, 41 esophageal polypoid lesions from 5698 endoscopic examinations were identified retrospectively. These included 24 patients with pathologically confirmed SPE, 11 patients with squamous hyperplasia, three patients with glycogenic acanthosis, two patients with ectopic sebaceous glands, and one patient with a xanthoma. In the χ2 test, exophytic growth (P = 0.003), a wart-like shape (P < 0.001), and crossing surface vessels under NBI (P = 0.001) were more frequently observed in SPE than in other lesion types. By contrast, there was no significant difference regarding the appearance of a whitish color between SPE and other lesion types (P = 0.872). The most sensitive characteristic was wart-like projections (81.3%) and the most specific was exophytic growth (87.5%). Promising positive predictive values of 84.2%, 80.8%, and 82.6% were noted for exophytic growth, wart-like projections, and surface vessel crossing on NBI, respectively.

CONCLUSION: The use of three key typical endoscopic appearances - exophytic growth, a wart-like shape, and vessel crossing on the lesion surface under NBI - has a promising positive predictive value of 88.2%. This diagnostic triad is useful for the endoscopic diagnosis of SPE.

Core tip: Esophageal superficial and flat lesions possess a wide spectrum of clinical and pathological features. Understanding the endoscopic features of these lesions is essential for their detection, differential diagnosis, and management. Squamous papilloma of the esophagus (SPE) is a rare benign esophageal lesion characterised by whitish and wart-like projections under conventional endoscopy. Overall, 88.2% of patients with polypoid lesions who presented all three typical endoscopic features (exophytic growth, a wart-like shape, and crossing surface vessels) were ultimately histologically confirmed as SPE. Our results may allow endoscopists to more confidently simply observe SPE that meets all endoscopic criteria.

- Citation: Wong MW, Bair MJ, Shih SC, Chu CH, Wang HY, Wang TE, Chang CW, Chen MJ. Using typical endoscopic features to diagnose esophageal squamous papilloma. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(7): 2349-2356

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i7/2349.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i7.2349

Esophageal superficial and flat lesions possess a wide spectrum of clinical and pathological features[1]. Understanding the endoscopic features of these lesions is essential for their detection, differential diagnosis, and management. Squamous papilloma of the esophagus (SPE) is a rare benign esophageal lesion characterised by whitish and wart-like projections under conventional endoscopy. The prevalence of SPE ranges from 0.07% to 0.45%[2,3]. Most SPEs are solitary and do not cause symptoms. The sex distribution is either predominantly male or gender neutral[3-6] and the mean age at diagnosis is in the 40s to 50s[3,5-7].

The etiology of SPE is not fully understood and at present, there are at least two etiological hypotheses. One concerns inflammatory reactions such as gastro-esophageal reflux disease or a chemical or mechanical mucosal injury[8-10]. The basis of this theory is the high percentage of SPE that occurs at the lower third of the esophagus[2,5,8]. Another hypothesis implicates human papilloma virus (HPV) infection[4,11,12]. However, the exact pathophysiological importance of HPV is not yet clear.

At times, tiny flat lesions that are recognised as SPE due to their small size are not pathologically diagnosed as SPE. Most of these lesions are pathologically diagnosed as squamous cell hyperplasia, glycogenic acanthosis, ectopic sebaceous glands, or xanthomas. The aim of the present study was to clarify the endoscopic characteristics of SPE that contribute to its discrimination from superficial esophageal lesion types.

Consecutive outpatients scheduled for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for upper gastrointestinal symptoms at our Endoscopy Centre between October 2009 and June 2014 were retrospectively analysed. The following data were collected from patient medical records: gender, age, indications for EGD, and endoscopic characteristics including lesion location, number, colour, size, surface morphology, surrounding mucosa, and surface vessels under narrow-band imaging (NBI). Lesion location was classified as the upper (less than 24 cm from the incisors), middle (between 24 and 32 cm from the incisors), or lower (more than 32 cm from the incisors) oesophagus. Lesion size was estimated using radial jaw biopsy forceps with a width of 6 mm when open (Boston Scientific, MA, United States). The key indications in patients undergoing EGD were epigastric pain, dysphagia, and acid regurgitation or heartburn. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mackay Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan (15MMHIS004).

We investigated the diagnostic yield of four key endoscopic characteristics of SPE: whitish colour, exophytic growth, a wart-like shape, and crossing surface vessels under NBI. Series endoscopy (Olympus GIF H260; Olympus Medical Systems Corp, Tokyo, Japan) with an NBI light source was performed in all cases. An evaluation of the entire esophagus was initially performed in a standardised manner by conventional white light endoscopy. Excess mucosal contents were removed using suction and flushes to produce a satisfactory view of the mucosa with no adherent mucus. After turning on the NBI light source, the entire esophagus was carefully scanned by NBI. Lesion specimens obtained by forceps biopsy were fixed in formalin and processed for pathological examination. For patients with multiple SPEs, at least two typical polyps were evaluated histologically. These series endoscopic images of each patient were reviewed by three experienced endoscopists with no prior access to the images. The endoscopists answered yes-or-no questions to determine whether each of the four key endoscopic characteristics was suggestive of an SPE diagnosis. A characteristic was considered positive if two or more endoscopists were in agreement.

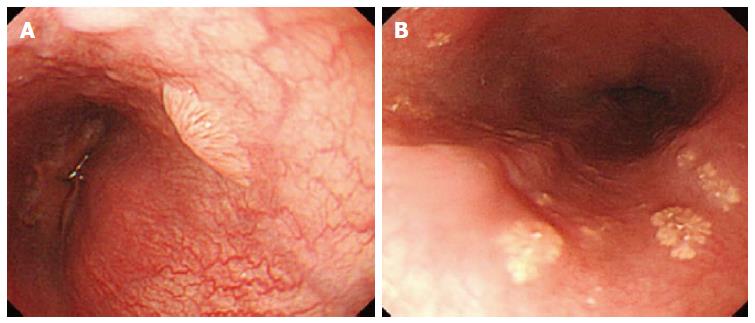

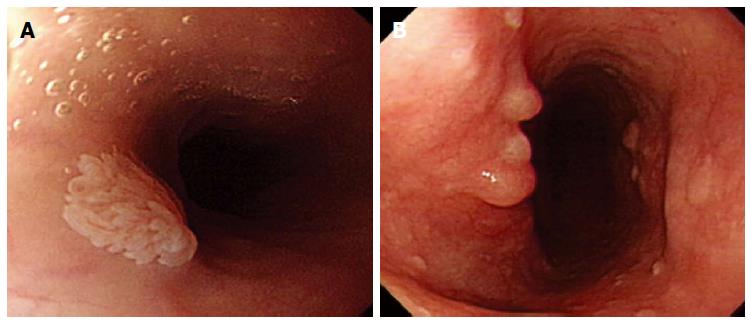

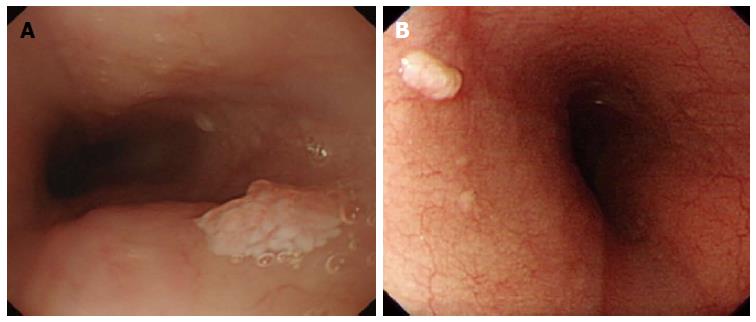

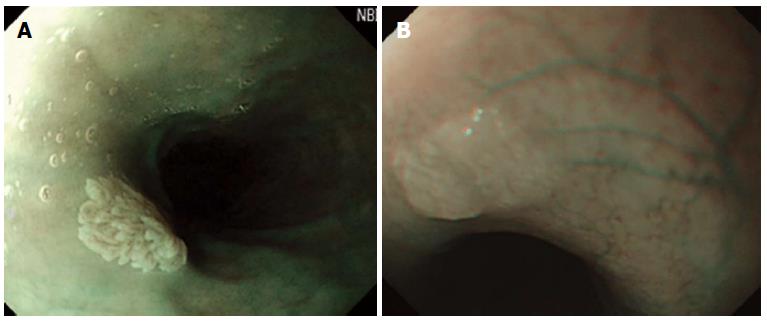

Whitish colour was defined as a lesion that looked pale compared to the normal pinkish oesophageal mucosa under either near or far focus (Figure 1A). Exophytic growth was defined as a lesion that not only bulged from the flat mucosa of the esophagus but also floated on the plane without complete attachment to the mucosa (Figure 2A). A wart-like shape was defined as a lesion with an irregular border but with a margin that could be easily distinguished from the normal esophageal mucosa (Figure 3A). To evaluate the fourth characteristic, endoscopy was switched to NBI mode for a more sensitive observation of the blood vessels. Vessel crossing was defined as brownish lines passing through the surface of the lesion (Figure 4A).

The size and location of the lesions as well as their endoscopic characteristics (whitish colour, exophytic growth, wart-like shape, and crossing surface vessels under NBI) were statistically analysed to determine the accuracy of SPE diagnosis. Categorical endoscopic data were compared using Fisher’s exact test or the χ2 test, as appropriate. Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± SD and were compared using the Student’s t-test. SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) was used for all statistical analyses. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. For SPE and the other diagnostic groups, each characteristic was evaluated independently for sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy.

During the study period, 41 patients who were diagnosed with esophageal polypoid lesions from among 5698 endoscopic examinations were retrospectively reviewed. These included 24 (0.42%) patients with pathologically confirmed SPE, 11 patients with squamous hyperplasia, three patients with glycogenic acanthosis, two patients with ectopic sebaceous glands, and one patient with a xanthoma. The characteristics of all patients are shown in Table 1. The average age of the 24 SPE patients was 48.9 years (range, 28-68 years) and they included more female patients than male patients (20 vs 4). The average SPE size was 3.9 mm (range, 2-8 mm). The most common location of SPE was the middle esophagus (57.5%), followed by the lower (26.1%) and upper (17.4%) esophagus. Solitary SPE was present in 22 of the 24 patients. The indications for EGD were epigastric pain in 15 (62.5%) patients, dysphagia in 1 (4.3%) patient, and acid regurgitation or heartburn in 8 (33.3%) patients. With the exception of the gender ratio, there were no significant differences in parameters such as age, lesion location, lesion size, lesion number, or EGD indication between SPE patients and the other diagnostic groups (Table 1).

| Characteristic | SPE | Others | P value | ||

| (n = 24) | (n = 17) | ||||

| Age (yr) | 48 | (26-68) | 53.3 | (27-70) | 0.197 |

| Gender | 0.014 | ||||

| Male | 4 | 16.6% | 9 | 53.9% | |

| Female | 20 | 82.7% | 8 | 47.1% | |

| Lesion character | 0.383 | ||||

| Location (upp/med/inf) | 5/13/6 | 21/54/25% | 10/6/2001 | 5.9/58.8/35.3% | |

| Size (mm) | 3.8 | (2-8) | 3.2 | (2-5) | 0.098 |

| Single lesion | 22 | 92.0% | 14 | 82.4% | 0.369 |

| Reason for EGD | 0.533 | ||||

| Epigastric pain | 15 | 62.5% | 13 | 76.5% | |

| Dysphagia | 1 | 4.3% | 1 | 5.9% | |

| Acid regurgitation and/or heart burn | 8 | 33.3% | 3 | 17.6% | |

Most lesions considered to be SPE were small but recognisable because of margins that were demarcated from the normal esophageal mucosa. We compared the statistical results of each characteristic between SPE and the other lesion types. In the χ2 test, exophytic growth (P = 0.003), a wart-like shape (P < 0.001), and crossing surface vessels under NBI (P = 0.001) were more frequently observed in SPE than in other lesion types. By contrast, there was no significant difference regarding the appearance of a whitish colour between SPE and other lesion types (P = 0.872).

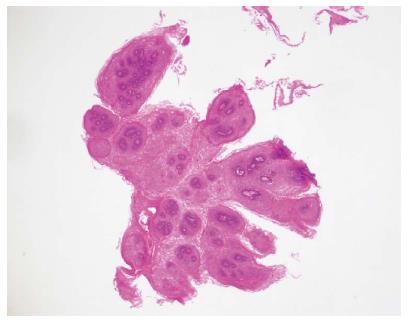

SPE was diagnosed pathologically by a hematoxylin and eosin stain showing many squamous cells surrounding the vascular connective tissue and forming finger-like projections (Figure 5). By comparison, only an increasing number of squamous cells in the epithelium were noted in squamous hyperplasia. After periodic acid-Schiff staining, glycogenic acanthosis exhibits a combination of cellular hyperplasia and increased cellular glycogen. A xanthoma consists of fat accumulation in foamy histiocytes beneath the squamous epithelium. An ectopic sebaceous gland appears as mucosa covered by benign squamous epithelium with a focal sebaceous cell component. There were no dysplastic or malignant components in these specimens.

Each characteristic was evaluated independently for sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy in SPE and the other diagnostic groups (Table 2). Among the typical endoscopic appearances, the most sensitive characteristic was wart-like projections (81.3%) and the most specific was exophytic growth (87.5%). Promising PPVs of 84.2%, 80.8%, and 82.6% were noted for exophytic growth, wart-like projections, and surface vessel crossing on NBI, respectively. However, fair NPVs of 61.9%, 78.9%, and 70.6% were noted for exophytic growth, wart-like projections, and surface vessel crossing on NBI, respectively. Using the diagnostic triad of exophytic growth, a wart-like shape, and surface vessel crossing under NBI achieved the highest PPV of 88.2% for SPE.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | |

| Whitish color | 79.2 | 18.8 | 59.4 | 37.5 | 55.0 |

| Exophytic growth | 66.7 | 81.3 | 84.2 | 61.9 | 72.5 |

| Wart-like projections | 87.5 | 68.8 | 80.8 | 78.6 | 80.0 |

| Surface vessel crossing on NBI | 79.2 | 75.0 | 82.6 | 70.6 | 77.5 |

| Combination of | 62.5 | 87.5 | 88.2 | 60.9 | 72.5 |

| exophytic growth, | |||||

| wart-like shape and surface vessel crossing |

A variety of benign esophageal lesions can be found during endoscopic evaluation. Although they are uncommon, cause no symptoms, and have no malignant potential, such lesions can pose a challenge for establishing an accurate diagnosis and a management plan. This study was the first to distinguish SPE from other tiny flat lesions in the esophagus using typical endoscopic appearances. We concluded that using three key endoscopic features of SPE, namely exophytic growth, a wart-like shape, and vessel crossing, can improve the diagnosis of SPE.

In our study, the average age of the 24 patients with SPE was 48.9 years, which is consistent with the fact that SPE is most commonly diagnosed in patients who are in their 50s[7,8]. Women were extremely dominant in our SPE population, with a male/female ratio of 1/4.75. In previous studies from Italy and other Western countries, most studies had male-dominant populations (male/female: 2.67/1 to 3.4/1)[5,9,11,13] or nearly equal sex distributions (male/female: 1.05/1 to 1/1.21)[2-4,6,14,15]. By contrast, one study in Japan reported a male/female ratio of 1/1.57[6]. Based on our study and the Japanese study, we suggest that there is a geographic difference whereby SPE is more common in women in Asia. Most reports from Western countries indicated a male predominance and a high prevalence of SPE in the lower third esophagus, which may be related to a high prevalence of erosive esophagitis. In our study, more than half of SPE (54.0%) cases occurred in the middle esophagus, similar to the Japanese study that reported a proportion of 52.6%. This suggests that the proposed inflammatory reactions due to gastro-esophageal reflux disease may not constitute the main aetiology of SPE in our patients.

HPV infection has been thought to be associated with SPE. The HPV infection rate in the SPE population has been variable (0 to 50%) and the relationship between HPV infection and SPE remains controversial[1,4-6,14]. HPV-positive SPE showed a female predominance, relatively young age, and high prevalence of a middle esophagus location[6]. It is possible that these differences may be related to geographic variability in the frequency of oral HPV infection. We do not know whether or not the female dominance of SPE in our study is related to the prevalence of HPV infection. Further prospective cohort studies would be mandatory to better evaluate the impact of HPV in the pathogenesis of SPE.

On EGD, SPE appear as small, whitish-pink, wart-like exophytic projections that must be differentiated from other similar-appearing lesions such as squamous cell hyperplasia, verrucous squamous cell carcinoma, glycogenic acanthosis, and other rare flat lesions such as heterotopic sebaceous glands or xanthomas. The majority of SPEs are solitary. In our study, all but two patients had multiple SPEs. Glycogenic acanthosis typically appears as multiple lesions that are believed to grow more numerous and larger with age. Xanthoma looks yellowish (Figure 1B) and glycogenic acanthosis often appears paler than the surrounding mucosa. SPE lesions not only bulged from the flat mucosa of the oesophagus, but also floated on the plane without complete attachment to the mucosa. In rare circumstances, however, SPE may appear as a sessile polypoid lesion tightly connected to the mucosa (Figure 2B). The border of SPE was irregular, but the margin could be easily distinguished from the normal esophageal mucosa. The border of squamous hyperplasia was also well-defined and the margin was clear (Figure 3B). SPE is characterised histologically by finger-like tissue projections lined by a core of connective tissue that contains small blood vessels. For this reason, several brownish lines could be observed passing through the surface of the SPE on NBI. By contrast, we observed no brownish lines on glycogenic acanthosis using NBI (Figure 4B).

Although the two lesion types occur in the same esophageal sites and papilloma occurs earlier, the different male-to-female ratios between these two lesion types may indicate that SPE does not share the same risk factors as esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Most studies indicated that SPE is generally a benign oesophageal lesion. However, there were a few case reports that presented papillomatosis of the esophagus with a squamous carcinoma component[16-20]. One study found synchronic planocellular carcinoma in a patient with SPE[4]. d’Huart et al[21] conducted a recent cohort study in France; during a median follow-up period of 21 mo, 2 esophageal squamous cell carcinomas were detected from 78 patients with SPE. The prevalence of associated cancer was 1.3 %. One carcinoma was located at the previous resection site of the SPE and the other was located at a different area. In these rare circumstances, SPE or papillomatosis should be surveyed for malignancy.

There were some limitations to the present study. The first is its retrospective design, in that the series endoscopic images of each patient were reviewed retrospectively. We do not know whether the endoscopist could judge these key characteristics accurately in real time. The clinical outcomes should be validated in a prospective study. Second, while we acquired images using multiple angles and focuses, we did not use magnifying endoscopy to obtain more detailed information. We do not know if magnifying endoscopy can provide more relevant key characteristics that would result in better outcomes. Third, all specimens were obtained using cold biopsy forceps. This may be a less accurate method for pathological evaluation than endoscopic resection.

Overall, 88.2% of patients with polypoid lesions who presented all three typical endoscopic features of SPE were ultimately histologically confirmed as SPE. The advantage of the study is in showing that the benign nature of SPE makes it possible to predict SPE using endoscopic criteria without histological examination. Data from the literature suggest that SPE is a generally benign lesion of the esophagus, except for papillomatosis or a large lesion. Our results may allow endoscopists to more confidently simply observe a single, small lesion in the oesophagus that meets all endoscopic criteria. This prevents unnecessary biopsy, especially for patients undergoing a non-sedative endoscopy that requires them to tolerate a longer biopsy procedure.

Squamous papilloma of the esophagus (SPE) is a rare benign esophageal lesion characterised by whitish and wart-like projections under endoscopy. However, some superficial tiny lesions that are recognised as squamous papilloma in the esophagus receive a different pathological diagnosis.

Narrow band imaging is composed of just two specific wavelengths that are strongly absorbed by haemoglobin. The shorter wavelengths (blue band) only penetrate the top layer of the mucosa, while the longer wavelengths (red band) penetrate deep into the mucosa. These wavelengths allow a better understanding of the vasculature of mucosal lesions.

The advantage of the study is in showing that the benign nature of SPE makes it possible to predict SPE using endoscopic criteria without histological examination.

The use of three key typical endoscopic appearances - exophytic growth, a wart-like shape, and vessel crossing on the lesion’s surface under narrow band imaging (NBI) - to predict SPE has a promising positive predictive value of 88.2%. This diagnostic triad is useful for the endoscopic diagnosis of SPE.

NBI is a powerful optical image enhancement technology that improves the visibility of blood vessels and other structures on the mucosa.

The authors did a retrospective study to analyse whether some key endoscopic appearances (whitish color, exophytic growth, wart-like shape, and surface vessels) and narrow band imaging can distinguish squamous papilloma from other types of benign lesions in the esophagus. They claimed that combination of three key typical endoscopic appearances-exophytic growth, a wart-like shape, and vessel crossing on the lesion’s surface under NBI-has a good positive predictive value, and this triad is useful for the endoscopic diagnosis of squamous papilloma.

P- Reviewer: Su CC S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Tsai SJ, Lin CC, Chang CW, Hung CY, Shieh TY, Wang HY, Shih SC, Chen MJ. Benign esophageal lesions: endoscopic and pathologic features. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1091-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Chang F, Janatuinen E, Pikkarainen P, Syrjänen S, Syrjänen K. Esophageal squamous cell papillomas. Failure to detect human papillomavirus DNA by in situ hybridization and polymerase chain reaction. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:535-543. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Sablich R, Benedetti G, Bignucolo S, Serraino D. Squamous cell papilloma of the esophagus. Report on 35 endoscopic cases. Endoscopy. 1988;20:5-7. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Szántó I, Szentirmay Z, Banai J, Nagy P, Gonda G, Vörös A, Kiss J, Bajtai A. [Squamous papilloma of the esophagus. Clinical and pathological observations based on 172 papillomas in 155 patients]. Orv Hetil. 2005;146:547-552. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Odze R, Antonioli D, Shocket D, Noble-Topham S, Goldman H, Upton M. Esophageal squamous papillomas. A clinicopathologic study of 38 lesions and analysis for human papillomavirus by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:803-812. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Talamini G, Capelli P, Zamboni G, Mastromauro M, Pasetto M, Castagnini A, Angelini G, Bassi C, Scarpa A. Alcohol, smoking and papillomavirus infection as risk factors for esophageal squamous-cell papilloma and esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma in Italy. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:874-878. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Takeshita K, Murata S, Mitsufuji S, Wakabayashi N, Kataoka K, Tsuchihashi Y, Okanoue T. Clinicopathological characteristics of esophageal squamous papillomas in Japanese patients--with comparison of findings from Western countries. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2006;39:23-30. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Fernández-Rodríguez CM, Badia-Figuerola N, Ruiz del Arbol L, Fernández-Seara J, Dominguez F, Avilés-Ruiz JF. Squamous papilloma of the esophagus: report of six cases with long-term follow-up in four patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:1059-1062. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Carr NJ, Monihan JM, Sobin LH. Squamous cell papilloma of the esophagus: a clinicopathologic and follow-up study of 25 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:245-248. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Parnell SA, Peppercorn MA, Antonioli DA, Cohen MA, Joffe N. Squamous cell papilloma of the esophagus. Report of a case after peptic esophagitis and repeated bougienage with review of the literature. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:910-913. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Carr NJ, Bratthauer GL, Lichy JH, Taubenberger JK, Monihan JM, Sobin LH. Squamous cell papillomas of the esophagus: a study of 23 lesions for human papillomavirus by in situ hybridization and the polymerase chain reaction. Hum Pathol. 1994;25:536-540. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Syrjänen KJ. HPV infections and oesophageal cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:721-728. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Franzin G, Musola R, Zamboni G, Nicolis A, Manfrini C, Fratton A. Squamous papillomas of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:104-106. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Mosca S, Manes G, Monaco R, Bellomo PF, Bottino V, Balzano A. Squamous papilloma of the esophagus: long-term follow up. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:857-861. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Poljak M, Orlowska J, Cerar A. Human papillomavirus infection in esophageal squamous cell papillomas: a study of 29 lesions. Anticancer Res. 1995;15:965-969. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Reynoso J, Davis RE, Daniels WW, Awad ZT, Gatalica Z, Filipi CJ. Esophageal papillomatosis complicated by squamous cell carcinoma in situ. Dis Esophagus. 2004;17:345-347. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Attila T, Fu A, Gopinath N, Streutker CJ, Marcon NE. Esophageal papillomatosis complicated by squamous cell carcinoma. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23:415-419. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Donnellan F, Walker B, Enns R. Esophageal papillomatosis complicated by squamous cell carcinoma. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E110-E111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Waluga M, Hartleb M, Sliwiński ZK, Romańczyk T, Wodołazski A. Esophageal squamous-cell papillomatosis complicated by carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1592-1593. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Wolfsen HC, Hemminger LL, Geiger XJ, Krishna M, Woodward TA. Photodynamic therapy and endoscopic metal stent placement for esophageal papillomatosis associated with squamous cell carcinoma. Dis Esophagus. 2004;17:187-190. [PubMed] |

| 21. | d’Huart MC, Chevaux JB, Bressenot AM, Froment N, Vuitton L, Degano SV, Latarche C, Bigard MA, Courrier A, Hudziak H. Prevalence of esophageal squamous papilloma (ESP) and associated cancer in northeastern France. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E101-E106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |