Published online Dec 28, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i48.10663

Peer-review started: August 6, 2016

First decision: September 28, 2016

Revised: October 20, 2016

Accepted: November 23, 2016

Article in press: November 28, 2016

Published online: December 28, 2016

Processing time: 144 Days and 21.5 Hours

To assess risk factors of hospital admission for acute colonic diverticulitis.

The study was conducted as part of the second wave of the population-based North Trondelag Health Study (HUNT2), performed in North Trondelag County, Norway, 1995 to 1997. The study consisted of 42570 participants (65.1% from HUNT2) who were followed up from 1998 to 2012. Of these, 22436 (52.7%) were females. The cases were defined as those 358 participants admitted with acute colonic diverticulitis during follow-up. The remaining participants were used as controls. Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses was used for each sex separately after multiple imputation to calculate HR.

Multivariable Cox regression analyses showed that increasing age increased the risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis: Comparing with ages < 50 years, females with age 50-70 years had HR = 3.42, P < 0.001 and age > 70 years, HR = 6.19, P < 0.001. In males the corresponding values were HR = 1.85, P = 0.004 and 2.56, P < 0.001. In patients with obesity (body mass index ≥ 30) the HR = 2.06, P < 0.001 in females and HR = 2.58, P < 0.001 in males. In females, present (HR = 2.11, P < 0.001) or previous (HR = 1.65, P = 0.007) cigarette smoking increased the risk of admission. In males, breathlessness (HR = 2.57, P < 0.001) and living in rural areas (HR = 1.74, P = 0.007) increased the risk. Level of education, physical activity, constipation and type of bread eaten showed no association with admission for acute colonic diverticulitis.

The risk of hospital admission for acute colonic diverticulitis increased with increasing age, in obese individuals, in ever cigarette smoking females and in males living in rural areas.

Core tip: We sought to determine what health related factors were together associated with later admission for acute colonic diverticulitis. The factors were derived from the North Trondelag Health Study (HUNT2) in Norway, the HUNT2 study, performed during 1995-1997. The study had 42570 participants who used Levanger Hospital as their primary hospital. They were observed until 2012. Following HUNT2, the participants contributed 611492 person-years of follow-up. In all, 358 cases had been admitted with acute colonic diverticulitis. In a multivariable analysis, increasing age and increasing Body Mass Index were associated with increased risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis in both gender. In females, cigarette smoking likewise increased the risk of admission. In males, breathlessness, a HUNT variable associated with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, increased the risk of admission. On the other hand, physical activity, constipation and type of bread eaten showed no association with admission for acute colonic diverticulitis.

- Citation: Jamal Talabani A, Lydersen S, Ness-Jensen E, Endreseth BH, Edna TH. Risk factors of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis in a population-based cohort study: The North Trondelag Health Study, Norway. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(48): 10663-10672

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i48/10663.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i48.10663

Diverticular disease of the colon is highly prevalent in Western populations and adds to the already rising expenditures in healthcare systems[1]. The prevalence of diverticular disease is age dependent and increases from 5% in the age group 30-39 years to 60% among those older than 80 years of age[2].

Acute diverticulitis is the most common complication of colonic diverticulosis[3], with increasing incidence and admission rates in recent years[4,5]. Acute diverticulitis may also recur in 9% to 23% of patients[6].

The heritability of diverticular disease has been estimated at 40% in a large Swedish twin study[7], and a number of lifestyle related risk factors have been attributed to acute colonic diverticulitis. Obesity, reduced physical activity, tobacco smoking and reduced dietary fiber intake have all been associated with increased risk of acute colonic diverticulitis, but few studies have been able to assess all these factors together[8-12].

The aim of the present study was to assess risk factors of hospital admission for acute colonic diverticulitis in a prospective population-based cohort study.

During 1995 to 1997, all residents in North Trondelag County, Norway, aged 20 years and older, were invited to participate in the second wave of the North Trondelag Health Study (HUNT2), a survey consisting of written questionnaires on health related topics, physical examinations and blood sampling[13]. In the present study, the population of the ten municipalities who used Levanger Hospital as the primary hospital was included, representing 73% of the population in North Trondelag County. The great majority are ethnic whites.

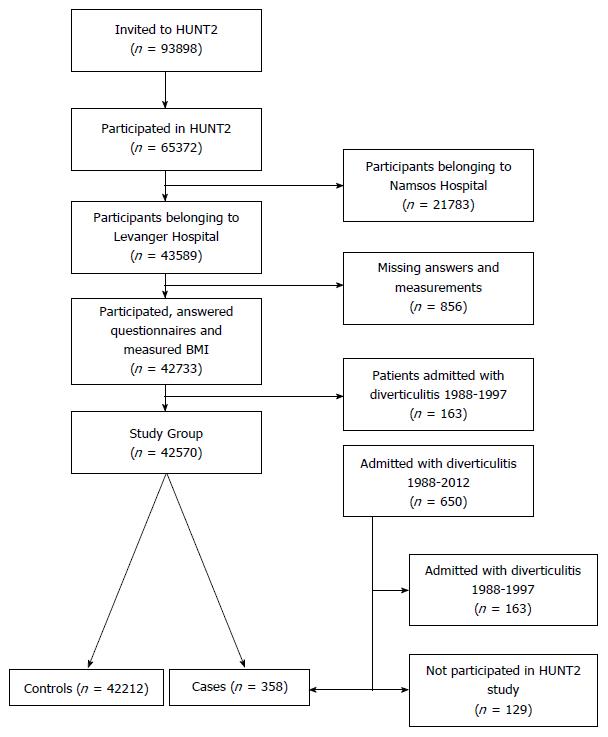

During 2012 and 2013 we retrospectively searched for all patients who had been admitted to Levanger Hospital following HUNT2, from 1998 to 2012, with the diagnosis acute colonic diverticulitis. The population of North Trondelag is served by two hospitals, Levanger Hospital is the largest and serving 10 municipalities. All treatment is given free of charge for the population. The patients were identified in the hospital patient administrative system, using the discharge codes for colonic diverticular disease in international classification of diseases ICD-9 and ICD-10. All the records were reviewed to ensure a higher probability of a correct diagnosis of acute colonic diverticulitis. All 358 patients who had been admitted with acute colonic diverticulitis and had participated in HUNT2 were included in the present study as cases, and the remaining HUNT2 participants from the same ten municipalities were used as controls. Figure 1 shows a flowchart of participants and patient inclusions.

A computed tomography (CT) scan had been performed during the hospital stay in 161 patients (45%) and later in 52 (14.5%) additional patients during outpatient follow-up. Colonoscopy had been performed in 139 (38.8%) patients. During the early years of the study (mainly between 1998 and 2006), a barium enema had been done in 120 (33.5%) patients to diagnose diverticula in the colon. One or more of these examinations had been performed in 331 patients (92.5%).

A full description of the questionnaires and measurements in HUNT2 is given at http://www.ntnu.edu/hunt/data/que. From HUNT2 we gathered data on sex, age, body mass index (BMI) and self-reported data on physical activity, cigarette smoking, duration of breathlessness, duration of constipation, main type of bread eaten, level of education and type of living area. Qualified personnel completed the standardized measurements of height and weight. Individuals were categorized as normal weight (with BMI < 25.0 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25-29.9) or obese (BMI ≥ 30), based on the World Health Organization’s classification[14]. Physical activity was categorized as hard physical activity less than or at least one hour per week. Cigarette smoking was reported as never, previous or present daily smoking. Both variables, “To what extent have you had problems with breathlessness the last 12 mo” and “To what extent have you had problems with constipation the last 12 mo”, were answered by the respondents as “not at all”, “slightly” or “very much”. Main type of bread eaten was categorized as “only fine” [white bread, white multigrain or whole meal (medium ground)], “only coarse” [multigrain, whole meal (coarsely ground)] or crisp bread, or “mixed” (mix of coarse and fine bread). Highest educational level was classified into primary school level or higher than primary school level. Living area was categorized as urban or rural area.

The primary study endpoint was the first admission for acute colonic diverticulitis at Levanger Hospital following participation in HUNT2, until end of study December 31, 2012. The observation time was measured from date of participation in HUNT2 to date of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis. All HUNT2 participants belonging to Levanger Hospital not admitted, were treated as controls. Their observation time was measured from date of participation in HUNT2 until end of study, December 31, 2012, date of death, or moving out of North Trondelag County, whichever occurred first.

Females and males were analysed separately. Six of the analysed risk factors had a large number of missing values; 54% of females and 46% of males had one or more missing values (Table 1).

| Variable | Females | Males |

| Hard physical activity | 39 | 28 |

| Cigarette smoking | 7 | 5 |

| Breathlessness | 16 | 10 |

| Constipation | 12 | 9 |

| Type of bread | 13 | 16 |

| Highest educational level | 6 | 5 |

To reduce bias and avoid loss of sample size, we used multiple imputation to handle these missing data. We imputed 100 data sets, as recommended by Carpenter and Kenward[15].

A Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariable analysis of risk factors of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis, providing hazard ratios (HRs) with 95%CIs. Two-sided P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

The analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) and StatXact 9 (Cytel Inc., Cambridge, MA, United States).

Statistical review of the study was performed by one of the authors, professor in medical statistics, Stian Lydersen.

The participants in HUNT2 gave written informed consent for medical research, including future linkage to patient records at the hospitals. The present study is approved by the Regional Committee for Health and Research Ethics (2011/1782/REK midt).

In HUNT2, 65372 persons attended (69.5% response rate). Of these, 42570 persons had Levanger Hospital as their primary hospital and were included in the present study. Following HUNT2, the participants contributed 611492 person-years of follow-up, and 358 cases were admitted with acute colonic diverticulitis (Figure 1). The remaining HUNT2 participants belonging to Levanger Hospital were used as controls, excluding the 129 persons who had been admitted with acute colonic diverticulitis during 1988 and 1997 (preceding HUNT2).

In the included cohort, 22436 (52.7%) were females. The mean age at baseline was 50.0 (SD 17.2) and 49.5 (SD 16.7) years for females and males, respectively. During follow-up, 358 participants were admitted to Levanger Hospital with acute colonic diverticulitis, 233 (65.1%) were females, and the mean age at admission was 69.3 (SD 13.2) and 63.9 (SD 14.1) years for females and males, respectively. Among the patients who had been admitted with acute colonic diverticulitis, but did not participate in HUNT2 (excluded from the present study), 54 (42%) were females, and the mean age at admission was 62.6 years (SD 16.0) for females, and 52.7 years (SD 16.6) for males.

Mean time from participation in HUNT2 to admission for acute colonic diverticulitis was 9.48 (SD 4.5) and 9.16 (SD 4.4) years for females and males, respectively.

Table 2 shows the sex-specific distribution of baseline characteristics of cases and controls. In both sexes, the age and BMI were higher and frequency of physical activity was lower among cases than controls. In females, more cases smoked cigarettes daily than controls. In both sexes, cases were more affected with breathlessness and constipation than controls. In both sexes, coarse type of bread was eaten more frequently in cases than controls. In both sexes, cases had lower educational level than controls. Among males, cases lived more often in a rural area than controls.

| Characteristic | Acute colonic diverticulitis 1998-2012 | |||

| Females | Males | |||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Study population | 22203 | 233 | 20009 | 125 |

| Age in years at inclusion | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 49.9 (17.2) | 59.8 (13.8) | 49.5 (16.7) | 54.7 (14.4) |

| Age groups (yr) | ||||

| < 50 | 11892 (99.5) | 57 (0.5) | 10787 (99.6) | 45 (0.4) |

| 50-70 | 6708 (98.4) | 112 (1.6) | 6307 (99.1) | 58 (0.9) |

| > 70 | 3603 (98.3) | 64 (1.7) | 2915 (99.3) | 22 (0.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| < 25 | 9987 (99.3) | 68 (0.7) | 6983 (99.6) | 26 (0.4) |

| 25-29.9 | 8206 (98.9) | 89 (1.1) | 10146 (99.4) | 64 (0.6) |

| ≥ 30 | 4010 (98.1) | 76 (1.9) | 2880 (98.8) | 35 (1.2) |

| Hard physical activity (h/wk) | ||||

| < 1 | 9346 (99.0) | 91 (1.0) | 8368 (99.3) | 58 (0.7) |

| ≥ 1 | 4286 (99.6) | 19 (0.4) | 6105 (99.4) | 36 (0.6) |

| Missing | 8571 (98.6) | 123 (1.4) | 5536 (99.4) | 31 (0.6) |

| Smoking cigarettes | ||||

| Never | 10134 (99.2) | 81 (0.8) | 7337 (99.6) | 31 (0.4) |

| Previous | 4137 (98.8) | 51 (1.2) | 6175 (99.2) | 52 (0.8) |

| Daily | 6295 (98.8) | 75 (1.2) | 5491 (99.4) | 33 (0.6) |

| Missing | 1637 (98.4) | 26 (1.6) | 1006 (99.1) | 9 (0.9) |

| Problems with breathlessness the last 12 mo | ||||

| Not at all | 17030 (99.1) | 155 (0.9) | 16585 (99.5) | 87 (0.5) |

| Slightly | 1434 (98.8) | 17 (1.2) | 1262 (98.5) | 19 (1.5) |

| Very much | 185 (98.4) | 3 (1.6) | 189 (98.4) | 3 (1.6) |

| Missing | 3554 (98.4) | 58 (1.6) | 1973 (99.2) | 16 (0.8) |

| Problems with constipation the last 12 mo | ||||

| Not at all | 13664 (99.1) | 125 (0.9) | 15690 (99.4) | 90 (0.6) |

| Slightly | 4640 (99.0) | 48 (1.0) | 2201 (99.4) | 14 (0.6) |

| Very much | 1213 (98.3) | 21 (1.7) | 285 (99.0) | 3 (1.0) |

| Missing | 2686 (98.6) | 39 (1.4) | 1833 (99.0) | 18 (1.0) |

| Type of bread | ||||

| Only fine | 2670 (99.0) | 28 (1.0) | 3798 (99.5) | 20 (0.5) |

| Mixed | 3158 (99.0) | 33 (1.0) | 4062 (99.4) | 23 (0.6) |

| Only coarse | 13440 (98.9) | 147 (1.1) | 9018 (99.3) | 62 (0.7) |

| Missing | 2935 (99.2) | 25 (0.8) | 3131 (99.4) | 20 (0.6) |

| Highest educational level | ||||

| Primary school | 8146 (98.7) | 110 (1.3) | 5519 (99.2) | 46 (0.8) |

| Above primary school | 12687 (99.3) | 95 (0.7) | 13536 (99.5) | 73 (0.5) |

| Missing | 1370 (97.3) | 28 (2.7) | 954 (99.4) | 6 (0.6) |

| Living area | ||||

| Urban | 18225 (98.9) | 195 (1.1) | 16425 (99.4) | 91 (0.6) |

| Rural | 3978 (99.1) | 38 (0.9) | 3584 (99.1) | 34 (0.9) |

Tables 3 and 4 shows the results of univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses for each sex separately after the multiple imputation. In the multivariable analysis, increasing age was associated with increased risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis in both sexes (HR = 3.42, 95%CI: 2.40-4.86, P < 0.001 for ages 50-70 years and HR = 6.19, 95%CI: 4.02-9.54, P < 0.001 for ages > 70 years in females). In males the corresponding values were HR = 1.85, 95% CI: 1.22 to 7.80, P = 0.004 and 2.56, 95%CI: 1.45-4.52, P < 0.001. Obesity was associated with increased risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis in both sexes (HR = 2.06, 95%CI: 1.46-2.91, P < 0.001 in females and HR = 2.58, 95%CI: 1.53-4.34, P < 0.001 in males). In females, both present and former daily cigarette smoking was associated with increased risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis (HR = 2.11, 95%CI: 1.51-2.94, P < 0.001 for daily smokers; HR = 1.65, 95%CI: 1.15-2.36, P = 0.007 for former smokers). In males, an increased risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis was observed in persons who reported slight problem with breathlessness during the last 12 mo (HR = 2.57, 95%CI: 1.55-4.28, P < 0.001) and in persons living in a rural area (HR = 1.74, 95%CI: 1.17-2.58, P = 0.007).

| Characteristic | Females | Males | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age in years (yr) | ||||

| < 50 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| 50-70 | 3.55 (2.58-4.89) | < 0.001 | 2.36 (1.60- 3.48) | < 0.001 |

| > 70 | 5.88 (4.10-8.44) | < 0.001 | 3.46 (2.06-5.79) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| < 25 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| 25-29.9 | 1.59 (1.16-2.18) | 0.004 | 1.62 (1.03-2.56) | 0.040 |

| ≥ 30 | 2.86 (2.06-3.97) | < 0.001 | 3.20 (1.93-5.31) | < 0.001 |

| Hard physical activity (h/wk) | ||||

| < 1 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| ≥ 1 | 0.46 (0.27- 0.77) | 0.003 | 0.85 (0.56-1.29) | 0.45 |

| Smoking cigarettes | ||||

| Never daily | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Formerly | 1.45 (1.04-2.01) | 0.027 | 2.12 (1.36- 3.13) | 0.001 |

| Present daily | 1.36 (1.01-1.83) | 0.043 | 1.49 (0.91- 2.44) | 0.11 |

| Problems with breathlessness the last 12 mo | ||||

| Not at all | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Slightly | 1.44 (0.87-2.36) | 0.15 | 3.09 (1.88- 5.08) | < 0.001 |

| Very much | 2.32 (0.76- 7.12) | 0.14 | 3.54 (1.13-11.2) | 0.031 |

| Problems with constipation the last 12 mo | ||||

| Not at all | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Slightly | 1.14 (0.82-1.60) | 0.44 | 1.25 (0.72-1.19) | 0.43 |

| Very much | 2.02 (1.29-3.18) | 0.002 | 2.35 (0.76-7.24) | 0.14 |

| Type of bread | ||||

| Only fine | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Mixed | 0.97 (0.58-1.61) | 0.90 | 1.03 (0.57-1.86) | 0.93 |

| Only coarse | 1.01 (0.67-1.51) | 0.96 | 1.26 (0.76-1.08) | 0.38 |

| Highest educational level | ||||

| Primary school | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Higher than primary school | 0.49 (0.37-0.64) | < 0.001 | 0.57 (0.39-0.82) | 0.002 |

| Living area | ||||

| Urban | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Rural | 0.92 (0.65-1.30) | 0.63 | 1.80 (1.21-2.67) | 0.004 |

| Characteristic | Females | Males | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age in years (yr) | ||||

| < 50 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| 50-70 | 3.42 (2.40-4.86) | < 0.001 | 1.85 (1.22-7.80) | 0.004 |

| > 70 | 6.19 (4.02-9.54) | < 0.001 | 2.56 (1.45-4.52) | 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| < 25 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| 25-29.9 | 1.25 (0.90-1.73) | 0.18 | 1.46 (0.92-2.32) | 0.11 |

| ≥ 30 | 2.06 (1.46-2.91) | < 0.001 | 2.58 (1.53-4.34) | < 0.001 |

| Hard physical activity (h/wk) | ||||

| < 1 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| ≥ 1 | 0.67 (0.39-1.15) | 0.15 | 1.03 (0.67-1.57) | 0.90 |

| Smoking cigarettes | ||||

| Never daily | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Formerly | 1.65 (1.15-2.36) | 0.007 | 1.45 (0.91-2.31) | 0.12 |

| Present daily | 2.11 (1.51-2.94) | < 0.001 | 1.38 (0.84-2.29) | 0.21 |

| Problems with breathlessness the last 12 mo | ||||

| Not at all | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Slightly | 1.12 (0.68-1.86) | 0.66 | 2.57 (1.55-4.28) | < 0.001 |

| Very much | 1.43 (0.45-4.59) | 0.55 | 2.48 (0.74-8.39) | 0.14 |

| Problems with constipation the last 12 mo | ||||

| Not at all | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Slightly | 1.05 (0.75-1.48) | 0.77 | 0.94 (0.53-1.66) | 0.82 |

| Very much | 1.54 (0.95-2.49) | 0.078 | 1.41 (0.43-4.68) | 0.57 |

| Type of bread | ||||

| Only fine | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Mixed | 1.08 (0.65-1.79) | 0.77 | 1.06 (0.58-1.93) | 0.85 |

| Only coarse | 0.93 (0.62-1.41) | 0.74 | 1.24 (0.74-2.07) | 0.41 |

| Highest educational level | ||||

| Primary school | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Higher than primary school | 1.13 (0.82-1.54) | 0.46 | 0.90 (0.61-1.33) | 0.60 |

| Living area | ||||

| Urban | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Rural | 0.92 (0.65-1.30) | 0.63 | 1.80 (1.21-2.67) | 0.004 |

Level of education, hard physical activity, constipation and type of bread eaten showed no association with the risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis.

We also carried out these analyses separately for each of the three age groups. Results were substantially the same (data not shown).

In another analysis, we excluded the variable breathlessness, and there were only insignificant changes in the HRs for all of the remaining variables.

The main finding of this prospective population-based cohort study was that obese individuals had twice the risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis compared to normal weight individuals. This association was found in both females and males. Moreover, previous and present daily cigarette smoking also increased the risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis in females. There was no association between hard physical activity, constipation or eating bread with fine or coarse grains and risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis.

The present study demonstrated an increased risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis by increasing age in both females and males. This is consistent with findings reported by other studies[4,16].

There was an increased risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis in obese persons (BMI ≥ 30). This is in agreement with other population-based studies. In two prospective cohort studies of males[17,18], the risk of acute colonic diverticulitis was 1.6 and 3.2 times higher among overweight individuals (BMI 25-29.9) and 1.8 and 4.4 times higher among obese individuals (BMI ≥ 30), compared with those of normal weight (BMI 18.5-4.9). In a prospective cohort study of females, the risk was 1.3 times higher for overweight and obese individuals[19]. A weakness with these studies was the sex-specific nature of the cohorts.

Previous studies found that physical activity, in general, decreased the risk of acute colonic diverticulitis[12,19]. However, the present study found no association between hard physical activity for at least one hour per week and admission for the disease after adjustments. Cigarette smoking has been associated with increased severity of acute colonic diverticulitis[10]. In the present study, daily smoking increased the risk of admission for the disease by 2.2-fold in females. Previous studies found that smoking increased the risk of acute colonic diverticulitis by 25%-60% in both sexes[20-22] and increased the risk of complicated diverticulitis by 2.7 to 3.6-fold[10,22]. However, drawbacks of these studies were small number of cases[10], sex-specific cohorts[20,21] or lack of adjustments for dietary and other lifestyle factors like physical activity[22].

A previous long term study from this area of patients admitted with acute colonic diverticulitis, revealed an increased long term mortality by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) of 10% (95%CI: 6.0-16) in[23]. In comparison, COPD was the cause of death in 4.2% (95%CI: 4.0-4.4) in the total population from the same area. This suggested a link between COPD and acute colonic diverticulitis, which was also found in another study[24]. In the present study, we wanted to elucidate the association between COPD and diverticulitis in another way. Duration of breathlessness was chosen as a proxy variable for COPD from HUNT2. The results of the present study showed that shortness of breath was associated with increased risk of admission for the disease. Few studies have previously studied the possible relationship between COPD and diverticulitis, although one other study, found that complicated diverticulitis was associated with pulmonary symptoms and problems in 23% of the cases[25].

In the present study, constipation was not associated with increased risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis. Similar, a recent multicenter study found no association between constipation and left-sided colonic diverticulosis[26], while in another study, constipation was considered a symptom of, rather than a direct risk factor for, acute colonic diverticulitis[27].

High dietary fiber intake is traditionally thought to be associated with decreased risk of diverticular disease[28,29], although high quality evidence is lacking[30,31]. In the present study, type of bread, whether fine or coarse, had no effect on the risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis. This is consistent with other studies, which found no association between cereals and acute colonic diverticulitis[21,32,33].

In the present study, males living in rural areas had 80% increased risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis. In two previous studies, the risk of acute colonic diverticulitis was slightly elevated in both sexes living in rural areas[16,34].

Aging showed increased risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis. Colonic diverticulosis can be considered a degenerative disease in which increasing age leads to weakness of supporting connective tissue and subsequent increase in intraluminal pressure and later increased risk of colonic diverticulitis. However, the exact mechanism of increased risk of diverticulitis in humans with aging is still unclear[35].

Obesity is shown to be a risk factor for diverticular disease and its complications[8,11,19,35]. One likely mechanism for development of acute colonic diverticulitis is that increased fat deposition in the mesentery act pro-inflammatory with activation of macrophages within the adipose tissue and subsequent increase in TNF-α. Translocation of luminal bacteria from the intestine to the systemic circulation due to impaired barrier function may also play a role in this pathogenesis[35].

Cigarette smoking causes changes in the colonic wall structure in patients with diverticular disease that are similar to changes found in blood vessels caused by smoking in other organs. In addition, smoking is thought to affect colonic motility and intraluminal pressure[36].

There is a possible coexistence between COPD and acute colonic diverticulitis. While smoking is a known risk factor for both diseases, it is unclear whether COPD is a risk factor or comorbidity in this context. Both inflammatory bowel disease and COPD share many similarities in inflammatory pathogenesis[37], but the mechanism behind the association between breathlessness and risk of acute colonic diverticulitis is poorly understood.

This study has a population-based design with a large sample size and high participation rate. This diminishes selection bias, strengthens the study power, reduces the risk of chance findings and facilitates subgroup analyses. The objective and uniform measurement of height and weight by qualified personnel minimized the risk of differential misclassification of BMI[38]. The prospective nature and use of standardized questionnaires on risk factors limits the potential for recall bias.

The population of North Trondelag County is stable, ethnic white, homogenous and representative of the Norwegian population, with the exceptions of a slightly lower average income and absence of a large city[39].

The wide range of exposure data collected in HUNT2 made it possible to adjust for a number of potential confounding factors, like symptoms of constipation and breathlessness, educational level and living area, which is seldom done in analyses of acute colonic diverticulitis. We used multiple imputation to account for missing data with the resulting more accurate HRs and more precise CIs and significance tests.

Many patients with acute colonic diverticulitis have vague symptoms, does not seek the doctor, and recover without antibiotics. Only part of all patients with this disease will be admitted to hospital. We are not aware of any change in admission policy for acute colonic diverticulitis during the study period. In addition to using the ICD-codes set by the doctor in charge at discharge, every hospital record was reviewed to ensure a higher probability of a correct diagnosis and prevent misclassifications[4]. Still, the diagnosis of acute colonic diverticulitis may have been incorrect in a minority of patients with known diverticulosis, who presented with pain in the lower abdomen, fever and an elevated CRP, without a CT scan.

CT scan is considered to be gold standard for the diagnosis of acute colonic diverticulitis. During the earlier years of this study, CT scan was used more infrequently. Even with the nowadays widespread availability of CT scans in many countries, we think it would be unadvisable due to radiation hazard, to perform CT scans in every patient with suspected uncomplicated, acute colonic diverticulitis.

Another limitation of the study is the 30% of non-participants in HUNT2. Non-participants, who were later admitted with acute colonic diverticulitis, were younger than participants in HUNT2: 7 and 9 years younger for females and males, respectively. Therefore, the study results may not be directly generalizable to a younger population. Some subjective variables that we used in the analysis, like symptom of breathlessness and type of bread eaten, could have led to information bias due to their questionnaires’ nature. Another limitation is possible biased estimates due to residual confounding, as there are always unknown confounders that are unaccounted for in such studies.

The results of the present study apply to patients with colonic diverticulitis that was severe enough to require admission to hospital. The conclusions cannot be transformed without reservations to patients with diverticulitis not admitted to hospital.

In conclusion, this large prospective population-based cohort study showed that increasing age was associated with increased risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis in both sexes. Obese individuals had twice the risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis compared to those with normal weight. Previous or present cigarette smoking increased the risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis in females. There was no association between constipation or eating bread with fine or coarse grains and admission for acute colonic diverticulitis.

The North Trondelag Health Study (HUNT) is performed through collaboration between HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU), North Trondelag County Council, Central Norway Health Authority, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. We want to thank clinicians and other employees at North Trondelag Hospital Trust for their support and for contributing to data collection in this research project.

Admission rates for acute colonic diverticulitis is increasing in the Western world. What health related factors are independently associated with diverticulitis?

During the North-Trondelag Health Study in Norway, the HUNT2 study, performed during 1995-1997, a number of health related variables were collected. The present investigation studied which factors were independently associated with later admission for acute colonic diverticulitis. The participants contributed 611492 person-years of follow-up.

This large study demonstrated the independent association between increasing age and increasing body mass index and risk of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis in both gender. In females, cigarette smoking likewise increased the risk of admission. In males, breathlessness, a HUNT variable associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, increased the risk of admission. On the other hand, physical activity, constipation and type of bread eaten showed no independent association with admission for acute colonic diverticulitis.

The results of this study may give further strength to argue for changes in lifestyle factors in a matter to possibly avoid acute colonic diverticulitis.

The study of a large population provides a useful overview of the various risk factors and their clinical impact.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Norway

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Asteria CR, Lakatos PL S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu WX

| 1. | Papagrigoriadis S, Debrah S, Koreli A, Husain A. Impact of diverticular disease on hospital costs and activity. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:81-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Peppas G, Bliziotis IA, Oikonomaki D, Falagas ME. Outcomes after medical and surgical treatment of diverticulitis: a systematic review of the available evidence. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1360-1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rafferty J, Shellito P, Hyman NH, Buie WD. Practice parameters for sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:939-944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 463] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jamal Talabani A, Lydersen S, Endreseth BH, Edna TH. Major increase in admission- and incidence rates of acute colonic diverticulitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:937-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nguyen GC, Sam J, Anand N. Epidemiological trends and geographic variation in hospital admissions for diverticulitis in the United States. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1600-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 6. | Andeweg CS, Mulder IM, Felt-Bersma RJ, Verbon A, van der Wilt GJ, van Goor H, Lange JF, Stoker J, Boermeester MA, Bleichrodt RP. Guidelines of diagnostics and treatment of acute left-sided colonic diverticulitis. Dig Surg. 2013;30:278-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Granlund J, Svensson T, Olén O, Hjern F, Pedersen NL, Magnusson PK, Schmidt PT. The genetic influence on diverticular disease--a twin study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1103-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dobbins C, Defontgalland D, Duthie G, Wattchow DA. The relationship of obesity to the complications of diverticular disease. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:37-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Papagrigoriadis S, Macey L, Bourantas N, Rennie JA. Smoking may be associated with complications in diverticular disease. Br J Surg. 1999;86:923-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Park NS, Jeen YT, Choi HS, Kim ES, Kim YJ, Keum B, Seo YS, Chun HJ, Lee HS, Um SH. Risk factors for severe diverticulitis in computed tomography-confirmed acute diverticulitis in Korea. Gut Liver. 2013;7:443-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rodríguez-Wong U, Cruz-Rubin C, Pinto-Angulo VM, García Álvarez J. [Obesity and complicated diverticular disease of the colon]. Cir Cir. 2015;83:292-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Strate LL, Liu YL, Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL. Physical activity decreases diverticular complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1221-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Krokstad S, Langhammer A, Hveem K, Holmen TL, Midthjell K, Stene TR, Bratberg G, Heggland J, Holmen J. Cohort Profile: the HUNT Study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:968-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 708] [Cited by in RCA: 873] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | WHO. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:i-xii, 1-253. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Carpenter JR, Kenward MG. Multiple Imputation and its Application. 1st ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. . |

| 16. | Hjern F, Johansson C, Mellgren A, Baxter NN, Hjern A. Diverticular disease and migration--the influence of acculturation to a Western lifestyle on diverticular disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:797-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rosemar A, Angerås U, Rosengren A. Body mass index and diverticular disease: a 28-year follow-up study in men. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:450-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Strate LL, Liu YL, Aldoori WH, Syngal S, Giovannucci EL. Obesity increases the risks of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:115-122.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hjern F, Wolk A, Håkansson N. Obesity, physical inactivity, and colonic diverticular disease requiring hospitalization in women: a prospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:296-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hjern F, Wolk A, Håkansson N. Smoking and the risk of diverticular disease in women. Br J Surg. 2011;98:997-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Wing AL, Trichopoulos DV, Willett WC. A prospective study of alcohol, smoking, caffeine, and the risk of symptomatic diverticular disease in men. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:221-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Humes DJ, Ludvigsson JF, Jarvholm B. Smoking and the Risk of Hospitalization for Symptomatic Diverticular Disease: A Population-Based Cohort Study from Sweden. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:110-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Edna TH, Jamal Talabani A, Lydersen S, Endreseth BH. Survival after acute colon diverticulitis treated in hospital. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1361-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lorimer JW, Doumit G. Comorbidity is a major determinant of severity in acute diverticulitis. Am J Surg. 2007;193:681-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chapman J, Davies M, Wolff B, Dozois E, Tessier D, Harrington J, Larson D. Complicated diverticulitis: is it time to rethink the rules? Ann Surg. 2005;242:576-581; discussion 581-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yamada E, Inamori M, Watanabe S, Sato T, Tagri M, Uchida E, Tanida E, Izumi M, Takeshita K, Fujisawa N. Constipation is not associated with colonic diverticula: a multicenter study in Japan. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:333-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Humes DJ, Spiller RC. Review article: The pathogenesis and management of acute colonic diverticulitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:359-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Aldoori W, Ryan-Harshman M. Preventing diverticular disease. Review of recent evidence on high-fibre diets. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:1632-1637. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Crowe FL, Balkwill A, Cairns BJ, Appleby PN, Green J, Reeves GK, Key TJ, Beral V. Source of dietary fibre and diverticular disease incidence: a prospective study of UK women. Gut. 2014;63:1450-1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Strate LL. Lifestyle factors and the course of diverticular disease. Dig Dis. 2012;30:35-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ünlü C, Daniels L, Vrouenraets BC, Boermeester MA. A systematic review of high-fibre dietary therapy in diverticular disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:419-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ornstein MH, Littlewood ER, Baird IM, Fowler J, North WR, Cox AG. Are fibre supplements really necessary in diverticular disease of the colon? A controlled clinical trial. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282:1353-1356. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Strate LL, Liu YL, Syngal S, Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL. Nut, corn, and popcorn consumption and the incidence of diverticular disease. JAMA. 2008;300:907-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Maguire LH, Song M, Strate LL, Giovannucci EL, Chan AT. Association of geographic and seasonal variation with diverticulitis admissions. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:74-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Spiller RC. Changing views on diverticular disease: impact of aging, obesity, diet, and microbiota. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:305-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Milner P, Crowe R, Kamm MA, Lennard-Jones JE, Burnstock G. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide levels in sigmoid colon in idiopathic constipation and diverticular disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:666-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Keely S, Talley NJ, Hansbro PM. Pulmonary-intestinal cross-talk in mucosal inflammatory disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:7-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Palta M, Prineas RJ, Berman R, Hannan P. Comparison of self-reported and measured height and weight. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115:223-230. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Statistics Norway. Statistical Yearbook of Norway. Oslo, Kongsvinger: Statistics Norway; 2014. . |