Published online Mar 21, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i11.3069

Peer-review started: October 17, 2015

First decision: November 13, 2015

Revised: November 27, 2015

Accepted: December 30, 2015

Article in press: December 30, 2015

Published online: March 21, 2016

Processing time: 149 Days and 12.4 Hours

Advanced gastric cancer (aGC), not amenable to curative surgery, is still a burdensome illness tormenting afflicted patients and their healthcare providers. Whereas combination chemotherapy has been shown to improve survival and tumor related symptoms in the frontline setting, second-line therapy (SLT) is subject to much debate in the scientific community, mainly because of the debilitating effects of GC, which would impede the administration of cytotoxic therapy. Recent data has provided sufficient evidence for the safe use of SLT in patients with an adequate performance status. Taxanes, Irinotecan and even some Fluoropyrimidine analogs were found to provide a survival advantage in this subset of patients. Most importantly, quality of life measures were also improved through the use of adequate therapy. Even more pertinent were the findings involving antiangiogenic agents, which would add measurable improvements without significantly jeopardizing the patients’ well-being. Further lines of therapy are cause for much more debate nowadays, but specific targeted agents have shown considerable promise in this context. We herein review noteworthy published data involving the use of additional lines of the therapy after failure of standard frontline therapies in patients with aGC.

Core tip: Patients with advanced gastric cancer who progress after first line therapy are usually perceived as unfit for additional treatments and are therefore denied life prolonging treatments which can also improve quality of life. We herein review the available evidence in favor of undertaking therapeutic interventions in these patients, be it conventional cytotoxic therapies or targeted therapies.

- Citation: Ghosn M, Tabchi S, Kourie HR, Tehfe M. Metastatic gastric cancer treatment: Second line and beyond. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(11): 3069-3077

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i11/3069.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i11.3069

Gastric cancer (GC) is estimated to be the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide and it ranks third in regards to cancer related mortality[1]. GC incidence is widely variable in accordance with geographic location, with the highest reported incidence in China and Japan. Conversely, the global incidence of GC has been dropping in the past few decades and this malignancy has become one of the least common in North America[1]. Despite the staggering improvements in the field of medical oncology, patients stricken with inoperable GC have a dismal prognosis and will invariably experience disease progression and subsequent death[2]. Moreover, approximately 50% of patients present with advanced disease at diagnosis and remain beyond the scope of curative intent[3]. Chemotherapy, consisting of Fluoropyrimidine (Flu) and Platinum (Pt)-based combination regimens, is widely accepted as a standard first-line therapy[4,5]. Irinotecan-based regimens have also been shown to be an acceptable alternative. Medically fit patients are to be considered for a three-drug chemotherapy regimen through the addition of an Anthracycline or Docetaxel[4,5] Such combination therapies provide a survival advantage of over ten months. Combining Trastuzumab with Flu-Pt further improved overall survival (OS) by approximately 4.2 mo when patients were rigorously selected for HER-2 over-expression (Immunohistochemistry 3+), a benefit that is quite comparable to the 4.8 mo conferred to patients with breast cancer through the addition of Trastuzumab, despite the caveats of cross-trial comparisons[6,7].

The role of second-line therapy (SLT) for mGC has been largely disputed among practitioners due to the added risk of exposing patients, with already declining performance status (PS) from escalating tumor burden, to highly toxic agents. Attesting to the discordance in therapeutic inclinations would be the rate of dispensation of SLT, which accounts for 14% of patients enrolled in western clinical trials as opposed to 75% of patients participating in Asian trial[8,9]. Even more disconcerting is that some data from European clinical practice report less than half of their mGC patients as recipients of SLT, whereas 67% of patients in Asian clinical practice would be considered candidates for SLT[10,11].

In recent years, the established notion, arguing against the use of additional chemotherapy in patients with mGC, is no longer valid. Several studies have demonstrated a survival benefit of chemotherapy compared to best supportive care (BSC), and the appropriate use of biological agents has further improved the benefit for these patients[12,13].

In this current review, we aim to explore the role of chemotherapy and targeted therapy in patients with inoperable, advanced GC (aGC). The role of further lines of therapy, in patients with refractory disease, will also be reviewed.

To date, there are no guidelines specifying standard SLT for mGC, but several studies have demonstrated a definite survival advantage of SLT when compared with BSC. Evidently, initial therapy, as well as PS, must be taken into consideration before selecting an appropriate therapeutic strategy.

Taxanes are some of the first agents to show promising results in the treatment of aGC. An early phase II study, using weekly infusions of Docetaxel (35 mg/m2), yielded disappointing results with a high rate of treatment related toxicities (90% grade II asthenia) and a median OS of 3.5 mo[14]. Two subsequent phase II trials readdressed the use of a three-weekly dosing of Docetaxel (75-100 mg/m2), in conjunction with Dexamethasone prophylaxis and early growth factor support to reduce treatment related toxicities[15,16]. Both trials resulted in a comparable response rate (RR) of approximately 17% and a median OS of 6 and 8.4 mo in patients with aGC who progressed after treatment with Flu and Pt regimens. Also comparable were the rates of adverse events while on treatment medication, with asthenia (32%) and neutropenia (18%) deemed manageable and non disrupting for the patients[15].

Retrospective analysis of a larger cohort of 154 patients, treated with Docetaxel monotherapy (75 mg/m2 every 3 wk) demonstrated that Docetaxel is both active and tolerable in the second-line setting of aGC, providing patients with a median OS of 7.2 mo (95%CI: 5.9-8.5)[17]. Despite ample early data suggesting benefit from Docetaxel in the second-line setting, there was no solid evidence that this approach did in fact improve survival and Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) until the COUGAR-02 study, a phase 3 randomised controlled trial, examined whether the addition of Docetaxel (75 mg/m2 every 3 wk) to active symptom control would affect OS and HRQoL[18]. Median OS showed a modest, yet statistically significant, improvement in favor of the treatment arm (5.2 mo vs 3.6 mo, HR = 0.67, P = 0.01) as adverse events were found to be controllable. Interestingly, patients receiving Docetaxel also showed improvement in terms of pain, nausea and vomiting and disease specific HRQoL measures including dysphagia and abdominal pain[18]. However, the potential selection bias in this study ought to compel practitioners to consider the results with care, since most patients had an adequate PS (100% ECOG 0-2; 83% ECOG 0-1) before their selection according to the strict enrolment criteria of the clinical trial. As such, it is essential that the patient’s overall health status be evaluated before any further treatment is considered.

The results of the COUGAR-02 trial, along with previously published literature, seem to bring forth sufficient evidence to resolve the controversy regarding the advantages of SLT in relapsed/refractory GC with Docetaxel monotherapy.

Despite their shared mechanism of action, Docetaxel and Paclitaxel deviate in terms of pharmacologic characteristic, drug resistance mechanisms and potential toxicities[19,20]. Such differences would serve as a proper rationale to examine the role of Paclitaxel as SLT for aGC.

Initial clinical data comes from a phase II trial investigating the use of Paclitaxel at a dose of 225 mg/m2 every three weeks in addition to an anthracycline. Paclitaxel was well tolerated with a median OS of 8 mo, RR of 22% and only mild adverse events. Of note, the investigators reported that 44% of patients had a significant relief of their disease related symptoms[21]. The ensuing CCOG0302 phase II study examined the use of weekly Paclitaxel (80 mg/m2)[22]. Comparable to the three-weekly schedule, weekly Paclitaxel showed a modest RR of 16%, median OS of 7.8 mo and mild toxicity consisting mostly of neutropenia (16%)[22].

A more recent phase III, multicenter, randomised, open-label (WJOG 4007) trial compared the efficacy of Paclitaxel and Irinotecan, another valuable component of the armamentarium for refractory GC, with positive results obtained in both cohorts, but no statistically significant differences advocating for the preferential use of one agent over the other[23]. RR, progression free survival (PFS) and OS were comparable between patients allocated to Paclitaxel and those receiving Irinotecan (20.9% vs 13.6%, P = 0.24; 3.6 mo vs 2.3 mo, P = 0.33; 9.5 mo vs 8.4 mo, P = 0.38)[23]. However, the WJOG 4007 study also had a potential selection bias since all patients were medically fit (ECOG 0-1) prior to enrolment, a fact that is noteworthy before SLT is considered. Another limitation would be the absence of placebo control to further validate the survival advantage over BSC, but since both agents have been shown to improve survival individually, it would be safe to assume that such an advantage does exist.

The aforementioned data indicate that the use of Paclitaxel is a reasonable recourse as SLT, on account of its anti-tumor effect and its role in alleviating disease related symptoms. It is still unknown whether some benefit exists between Paclitaxel and Irinotecan in this setting since the comparative study between both agents was limited by a relatively small sample size and was underpowered to make such conclusions[23].

The Topoisomerase I inhibitor Irinotecan had been shown to be active in colorectal cancers and was later investigated in aGC having progressed after first-line therapy. Initial phase II studies explored the efficacy of single agent Irinotecan administered weekly (100 mg/m2), every two weeks (150 mg/m2) and every three weeks (350 mg/m2)[24-26]. The RR and median OS for these studies were in the range of 20% and 5 mo respectively, pointing to Irinotecan as an active and well tolerated regimen in the studied context[24-26]. More methodologically robust evidence came in the form of two phase III trial, which further confirmed the survival advantage gained by salvage chemotherapy and also provided additional substantiation in regards to the efficacy of Irinotecan[27,28].

The German AIO (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie) trial, despite its poor accrual, showed a statistically significant improvement in OS favoring Irinotecan (250 mg/m2 every three weeks to be increased to 350 mg/m2 depending on toxicity) over BSC (2.4 mo vs 4.0 mo for irinotecan; HR = 0.48, 95%CI: 0.25-0.92, P = 0.012) as well as a marked improvement in tumor related symptoms (50% vs 7%)[27].

On the other hand, participants in the Korean phase III trial were randomised to BSC, Irinotecan (150 mg/m2 every two weeks) or Docetaxel (60 mg/m2 every three weeks)[28]. At the time of data analysis, SLT was once again shown to be superior to BSC with a median OS of 5.3 mo as opposed to 3.8 mo in the control arm (HR = 0.657, 95%CI: 0.485-0.891, P = 0.007). Neither agent was found to be superior to the other in this setting (Docetaxel median OS: 5.2 mo, Irinotecan median OS: 6.5 mo, P = 0.116)[28].

The amount of data available seems satisfactory to justify the use of Docetaxel, Paclitaxel or Irinotecan in patients with aGC progressing after initial therapy, provided their overall PS allows the administration of additional cytotoxic agents, particularly since the prognosis remains poor in those patients and QOL remains an essential objective to achieve.

S-1, an oral Flu widely used in Japan after showing promising activity in aGC, has also been prospectively evaluated in patients who progressed after initial Pt/Flu therapy[29,30]. Although the evaluating phase II study does not provide compelling evidence as to the favorable effect of S-1, a modest RR of 14.0% was achieved along with a median OS of 6.3 mo[31]. Surprisingly, such results were achieved regardless of prior exposure to Flu, but the most noticeable attribute of this agent was its favorable adverse events profile since grade 3/4 toxicities were reported to be uncommon[31]. As such, S-1 might be considered as a useful therapeutic alternative in patients with a poor PS, especially in patients who haven’t received prior Flu containing regimens.

Nanoparticle albumin-bound Paclitaxel (nab-Paclitaxel) is another agent that has shown promising activity in previously treated GC. A multicenter phase II trial yielded a RR of 27.8% and median OS of 9.2 mo but with a relatively high, albeit manageable, rate of grade 3/4 adverse events in the form of neutropenia (49%) and peripheral sensory neuropathy (23.6%)[32]. Fortunately, the ongoing phase III (ABSOLUTE) trial aims to compare the efficacy of nab-Paclitaxel to Cremophor-based Paclitaxel and seeks to enrol a total of 730 patients with GC refractory to initial therapy across 72 institutions, a feat that will undoubtably shed more light on the treatment of this malignancy[33].

Single agent cytotoxic therapy clearly put an end to the debate regarding the value of SLT in refractory GC. Nevertheless, the role of combination chemotherapy in this context is still open to controversy.

Flu do not seem to be falling out of favor even though it has become an integral part of all front-line approaches for aGC. This continued interest has led investigators to assess the combination of biweekly Irinotecan with 5-fluorouracil, and Leucovorin (FOLFIRI) in patients with refractory disease.

Two different retrospective analysis produced encouraging results for the use of FOLFIRI, with overall RR of 12.3% and 22.8% but strikingly similar OS of 6.4 mo[34,35]. Subsequent prospective evaluations of a modified FOLFIRI regimen also showed positive results with RR and median OS ranging from 10% to 29% and 6.2 mo to 10.9 mo respectively[36,37]. It appears that FOLFIRI also provided improvements in regards to tumor-related symptoms. Although much of the available data points to potential benefit from FOLFIRI in refractory GC, a more recent phase II study comparing the combination regimen to Irinotecan monotherapy showed that both approaches are of equal activity but without any statistical difference in RR or OS between both treatment arms (5.8 mo Irinotecan, 6.7 mo FOLFIR, P = 0.514)[38]. This study is certainly underpowered to make definitive conclusions in the absence of larger phase III trials, yet the need to incorporate an additional cytotoxic agent into an already successful therapeutic strategy is largely put into question, mainly because of the resulting toxicities without securing any significant clinical benefits (higher incidence of grade 3/4 hematologic toxicity: anemia 10% vs 0 %; neutropenia 37% vs 28 %)[38].

Other studies investigating the re-introduction of Flu analogues in addition to Oxaliplatin revealed a remarkable rate of peripheral neuropathy, possibly potentiated through the prior use of Cisplatin[39]. Even when Oxaliplatin was administered at a lower dose, these regimens proved to be inadequate for the target population since they only procured modest[40].

To date, we still do not have sufficient evidence to recommend combination chemotherapy in patients with aGC who progressed on prior therapy. The survival benefit as well as the advantage in terms of symptoms palliation are only sensibly proven in patients receiving monotherapy. Approved cytotoxic agents in second-line aGC are summarized in Table 1.

| Ref. | Patients/phase | Treatment | Indication | Results (PFS/OS/RR) (mo) |

| Ford et al[18], 2014 | 168/III | Docetaxel | Advanced, gastric cancer that had progressed on or within 6 mo of treatment with a platinum-fluoropyrimidine combination | OS: 5.2 |

| COUGAR-02 | Active symptom control | OS: 3.6 | ||

| Kang et al[28], 2012[28] | 202/III | Docetaxel | Advanced gastric cancer with one or two prior chemotherapy regimens involving both fluoropyrimidines and platinum | 5.2 |

| Irinotecan | 6.5 | |||

| BSC | 3.8 |

Although chemotherapy is often effective in inducing early tumor destruction in most patients with metastatic disease, intra-tumor heterogeneity is associated with certain subpopulations of cancer cells that manage to evade the overwhelming cytotoxic effect through innate and acquired mechanisms of resistance. Recent developments in the field of molecular biology allowed a more precise targeting of tumor cells, or surrounding tissue, in order to try and circumvent some of these resistance mechanisms and avoid damaging non-malignant tissue. Even when target therapy is administered, tumor cells eventually manage to overcome the drug-induced signal transduction blockade by reactivating alternate signaling pathways[41]. Nevertheless, the biologic effects of these therapies translate into clinical benefit harvested by practitioners to ensure the best interest of their patients.

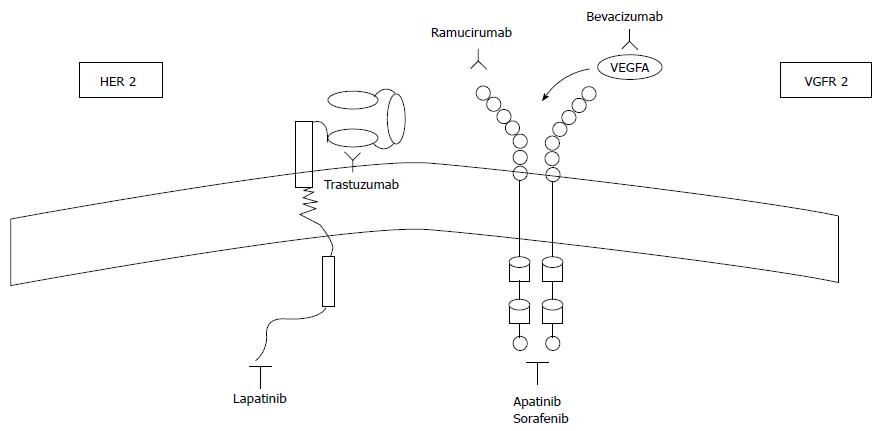

Since the results of the phase III ToGA trial were published, patients with aGC and HER-2 over-expression, which account for 7%-34% of patients, became candidates for a new standard therapy that consists of adding Trastuzumab to Flu and Pt-based frontline therapy[42-44]. Following the success of Trastuzumab in non-resectable GC, the sensible next step was to evaluate the efficacy of Lapatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor with dual potent inhibition of ErbB-1 and ErbB-2, in HER-2 positive GC that not amenable to curative therapy and having progressed after initial therapeutic strategies[45]. A phase II study examining the role of Lapatinib combined with Capecitabine was closed prematurely for futility[46]. Furthermore, the TyTan study, a phase III randomised trial, assessing the efficacy of Lapatinib in combination with Paclitaxel failed to demonstrate a significant survival advantage when compared with the control arm[47]. However, patients with tumors determined to be HER-2 3+ on immunohistochemistry did have a statistically significant improvement in PFS (5.6 mo vs 4.2 mo, HR = 0.54, 95%CI: 0.33-0.90, P = 0.0101) and Chinese patients exhibited an improvement in OS (9.7 mo vs 7.6 mo, P = 0.0351). Regardless of these findings, the TyTan study did not provide compelling evidence for the use of Lapatinib in refractory HER-2 positive GC. These findings are somewhat comparable to the experience of HER-2 targeted therapy in breast cancer, where Lapatinib has consistently fallen short of Trastuzumab in terms of efficacy[42,48]. One phase II study managed to provide evidence for the efficacy of Trastuzumab in the second-line setting, provided patients did not benefit from it in the front-line setting. Combining Trastuzumab with Paclitaxel produced and overall RR of 37.2% (95%CI: 23.0%-53.3%) and median PFS of 5.2 mo (95%CI: 3.9-6.6)[49].

Another attempt at precision therapy consisted of using anti-angiogenic agents. The first assessment of a similar strategy involved the addition of Bevacizumab to standard frontline therapy in the AVAGAST study, a phase III randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled trial[50]. However, this study did not reach its primary objective of a statistically significant improvement in OS, but it did demonstrate a significant improvement in RR (46.0% vs 37.4%, P = 0.0315) and PFS (6.7 mo vs 5.3 mo, HR = 0.80, 95%CI: 0.68-0.93, P = 0.0037)[51]. Moreover, participants from Pan-America did experience an impressive improvement in OS (11.5 mo vs 6.8 mo, HR = 0.63, 95%CI: 0.43-0.94) since only 21% were switched to second line therapy, as opposed to 66% of asian participants who actually received subsequent therapy[50]. The results of the AVAGAST study, with particular emphasis on the subgroup analysis, provided a foundation that would attest for the efficacy of anti-angiogenesis in GC. The MAGIC-B trial investigating the efficacy of Bevacizumab in the peri-operative setting of GC would also attest to the potential value of angiogenesis blockage, which could have prompted researchers to evaluate this strategy in patients being managed with curative intent[51].

Two landmark trials managed to validate the role of Ramucirumab, a monoclonal antibody inhibiting VEGFR-2, as a valuable addition to SLT in aGC (Figure 1).

The RAINBOW trial, a double-blind, phase III, randomised trial, indicated that the addition of Ramucirumab to Paclitaxel would result in a significant survival advantage when compared with Paclitaxel monotherapy, with a median OS of 9.6 mo [(95%CI: 8.5-10.8) vs 7.4 mo (95%CI: 6.3-8.4), HR = 0.807 (95%CI: 0.678-0.962), P = 0.017]; PFS of 4.4 mo vs 2.9 mo (HR = 0.635, P < 0.0001) and an objective RR of 28% vs 16% (P < 0.0001)[52]. The combination therapy also resulted in an increased of adverse events including neutropenia (but not febrile neutropenia) and hypertension, but global quality of life scores were similar in both treatment arm, attesting to the tolerability of adding the anti-angiogenic[53].

The results of the RAINBOW trial raised many questions concerning the treatment of aGC, most importantly regarding the efficacy of anti-angiogenesis in the second-line setting and not the first-line. It remains unclear whether the absence of perceivable benefit in the AVAGAST study is due to a diluted effect by the rate of administration of SLT or if it is mainly due the inherent GC pathophysiology, through which progression to more advanced stages under cytotoxic therapy leads to a molecular phenotype switch that is more reliant on angiogenesis[50]. The role of a synergistic chemotherapy agent used with Ramucirumab could have been debated, with some agents believed to be able to potentiate the anti-angiogenic effect, but the results of the REGARD trial probably put these arguments to rest.

The REGARD trial is another milestone trial promoting the efficacy of Ramucirumab as SLT of aGC. In this randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial, Ramucirumab monotherapy significantly improved survival with a median OS of 5.2 mo vs 3.8 mo for placebo (HR = 0.776, 95%CI: 0.603-0.998, P = 0.047) and a PFS of 2.1 mo vs 1.3 mo for placebo (P < 0.0001)[52]. A similar adverse events profile was noted for both treatment arms, except for hypertension, which was higher in the Ramucirumab monotherapy arm (16% vs 8%)[52].

Findings from both trials highlight the crucial importance of targeting angiogenesis in GC. Whereas the absolute gain in terms of survival was seen in the combination therapy, the relative safety profile of Ramucirumab monotherapy would encourage its use in patients with a relatively poorer PS, since a great number of patients seen in daily practice do not necessarily fulfil the strict inclusion criteria of these trials (ECOG 0-1 in both trials). All the approved targeted therapies in second-line aGC are summarized in Table 2.

| Ref. | Patients/phase | Treatment | Indication | Results (PFS/OS/RR) (mo) |

| Iwasa et al[49], 2013 | 46/II | Paclitaxel + Trastuzumab | HER2-positive, metastatic gastric cancer patients naive to trastuzumab, who received one or more lines of chemotherapy | ORR: 37.2% PFS: 5.2 |

| Wilke et al[53], 2014 RAINBOW | 665/III | Paclitaxel + Ramicirumab Paclitaxel + Placebo | Advanced gastric cancer and disease progression on or within 4 mo after first-line chemotherapy (platinum plus fluoropyrimidine with or without an anthracycline) | OS: 9.6 OS: 7.4 |

| Fuchs et al[52], 2015 REGARD | 355/III | Ramicirumab Placebo | Advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma and disease progression after first-line platinum-containing or fluoropyrimidine-containing chemotherapy | OS: 5.2 OS: 3.8 |

Over the past few years, multiple key signaling pathways regulating GC tumorigenesis have been identified and these include Epidermal Growth Factor, Fibroblast Growth Factor receptor, Hepatocyte Growth Factor, mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (c-MET) axis, the PI3K-AKT-mTOR and RAS/RAF/MEK/MAPK pathways, but the clinical significance of aberrations in these pathways remains uncertain[54]. Studies investigating the blockade of these pathways through the use of Cetuximab, Panitumumab, Gefitinib and Erlotinib in the treatment of GC have not produced sufficient evidence to recommend implementation in clinical practice[55]. Additionally, mTOR blockade, using Everolimus, did not significantly improve survival in previously treated aGC[56].

Presently, the only targeted therapy of identified clinical value would rely on the use of Trastuzumab in the subset of eligible patients who did not receive it in the first line setting as well as Ramucirumab monotherapy or in combination with Paclitaxel, unless otherwise contra-indicated.

Very few studies have investigated the use of chemotherapy in the third-line setting, mainly due to the absence of consensus in respect to the role of SLT. Notwithstanding, there is currently sufficient data to support the use of SLT in aGC, but with this renewed interest in SLT comes the debate of whether further lines of therapy should be considered in patients who can still tolerate it.

One retrospective Japanese study sought to determine the potency of tri-weekly Paclitaxel in a population of patients deemed refractory to Irinotecan, Flu and Pt. Paclitaxel induced a RR of 23.2%, a PFS of 3.5 mo and OS of 6.7 mo[57]. Most patients had a good performance status (82%% ECOG 0-1 and 18% ECOG 2) but there was some concern for the relatively considerable rate of adverse events with more than 25% of patients experiencing hematologic toxicities and up to eight percent having febrile neutropenia[58]. Another retrospective study suggested that Docetaxel salvage therapy might be feasible in patients with aGC, but there were many limitations, making it difficult to draw any relevant conclusions other than chemotherapy ought to be reconsidered in patients with a poor PS (ECOG > 1)[58]. A larger retrospective study exploring the survival advantage of salvage therapy indicated a modest RR of 9.6% in patients treated with FOLFIRI regimens. The authors inferred that there was a positive anti-tumor activity and that toxicities were tolerable[59]. Such conclusion should be interpreted with extreme caution in patients with progressive GC who would be subjected to a 36.7% rate of grade 3/4 myelosuppression.

In this context, more optimistic results were reported from a placebo-controlled phase II trial investigating a novel small-molecule VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, Apatinib, which has a binding affinity ten times that of other drugs such as Sorafenib[60,61]. The study enrolled 144 patients who were previously treated with at least two lines of therapy and showed a statistically significant improvement in terms of PFS (3.67 mo vs 1.40 mo, 95%CI: 2.17-6.80 mo, P < 0.001) and OS (4.5 mo vs 2.5 mo, 95%CI: 2.37-4.53 mo, P = 0.0017). This agent caused few “acceptable” adverse events, mainly in the form of hypertension and hand-foot syndrome, making it the most suitable treatment for heavily pretreated patients even if their PS would theoretically make them candidates for cytotoxic therapy.

Engaging the host’s immune response was another attempt to convey treatment to patients with pretreated GC. Inhibiting the interaction between the Programmed Death receptor (PD-1) and its ligand, Programmed Death Ligand 1, has led to astonishing results in cancer therapy[62]. Pembrolizumab, a humanised IgG4/kappa isotype monoclonal antibody targeting PD-1, was tested in patients with GC who progressed after SLT. Immunotherapy achieved an impressive overall RR of 30% and was found to be well tolerated by the participants[63]. These results are likely to usher in a new a era in the treatment of GC, probably extending to earlier lines of therapy in the very near future.

In spite of all the therapeutic milestones achieved in recent years, surgery remains the only curative treatment modality. For those patients not amenable to surgery, chemotherapy offers an improvement in quality of life as well as a survival advantage. However, responses are short lived and the disease invariably progresses. A few studies have established the role of chemotherapy in the second-line setting, proving that many agents are capable of extending survival and providing symptom palliation. Unfortunately, whether it’s Irinotecan, S-1, Docetaxel or Paclitaxel, no single approach is unanimously embraced until this day. It is also reasonable to include Ramucirumab in the therapeutic strategy in light of recent findings. As for patients who progress beyond SLT, treatment should be considered very carefully, as to avoid unwanted toxicities that would do more harm than good. Apatinib and Pembrolizumab offer considerable opportunities for the near future, but their value is still to be weighed in larger trials.

P- Reviewer: Xu WX, Zhu YL S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Globocan I. National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2011 [EB/OL]. Available from: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2011/indexeh.htm. |

| 2. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9172] [Cited by in RCA: 9956] [Article Influence: 995.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chau I, Norman AR, Cunningham D, Waters JS, Oates J, Ross PJ. Multivariate prognostic factor analysis in locally advanced and metastatic esophago-gastric cancer--pooled analysis from three multicenter, randomized, controlled trials using individual patient data. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2395-2403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 397] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wagner AD, Unverzagt S, Grothe W, Kleber G, Grothey A, Haerting J, Fleig WE. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD004064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, Majlis A, Constenla M, Boni C, Rodrigues A, Fodor M, Chao Y, Voznyi E. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991-4997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1331] [Cited by in RCA: 1457] [Article Influence: 76.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Okines AF, Dewdney A, Chau I, Rao S, Cunningham D. Trastuzumab for gastric cancer treatment. Lancet. 2010;376:1736; author reply 1736-1737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, Fleming T, Eiermann W, Wolter J, Pegram M. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8204] [Cited by in RCA: 8127] [Article Influence: 338.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, Iveson T, Nicolson M, Coxon F, Middleton G, Daniel F, Oates J, Norman AR. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:36-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1579] [Cited by in RCA: 1688] [Article Influence: 99.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, Takagane A, Akiya T, Takagi M, Miyashita K, Nishizaki T, Kobayashi O, Takiyama W. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:215-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1320] [Cited by in RCA: 1420] [Article Influence: 83.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Monti M, Foca F, Casadei Gardini A, Valgiusti M, Frassineti GL, Amadori D. Retrospective analysis on the management of metastatic gastric cancer patients. A mono-institutional experience. What happens in clinical practice? Tumori. 2013;99:583-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Elsing C, Herrmann C, Hannig CV, Stremmel W, Jäger D, Herrmann T. Sequential chemotherapies for advanced gastric cancer: a retrospective analysis of 111 patients. Oncology. 2013;85:262-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Casaretto L, Sousa PL, Mari JJ. Chemotherapy versus support cancer treatment in advanced gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39:431-440. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Iacovelli R, Pietrantonio F, Farcomeni A, Maggi C, Palazzo A, Ricchini F, de Braud F, Di Bartolomeo M. Chemotherapy or targeted therapy as second-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer. A systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Graziano F, Catalano V, Baldelli AM, Giordani P, Testa E, Lai V, Catalano G, Battelli N, Cascinu S. A phase II study of weekly docetaxel as salvage chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:1263-1266. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Lee JL, Ryu MH, Chang HM, Kim TW, Yook JH, Oh ST, Kim BS, Kim M, Chun YJ, Lee JS. A phase II study of docetaxel as salvage chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer after failure of fluoropyrimidine and platinum combination chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:631-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Giuliani F, Gebbia V, De Vita F, Maiello E, Di Bisceglie M, Catalano G, Gebbia N, Colucci G. Docetaxel as salvage therapy in advanced gastric cancer: a phase II study of the Gruppo Oncologico Italia Meridionale (G.O.I.M.). Anticancer Res. 2003;23:4219-4222. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Jo JC, Lee JL, Ryu MH, Sym SJ, Lee SS, Chang HM, Kim TW, Lee JS, Kang YK. Docetaxel monotherapy as a second-line treatment after failure of fluoropyrimidine and platinum in advanced gastric cancer: experience of 154 patients with prognostic factor analysis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37:936-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ford HE, Marshall A, Bridgewater JA, Janowitz T, Coxon FY, Wadsley J, Mansoor W, Fyfe D, Madhusudan S, Middleton GW. Docetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma (COUGAR-02): an open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:78-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in RCA: 442] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liu B, Staren ED, Iwamura T, Appert HE, Howard JM. Mechanisms of taxotere-related drug resistance in pancreatic carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2001;99:179-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Reinecke P, Schmitz M, Schneider EM, Gabbert HE, Gerharz CD. Multidrug resistance phenotype and paclitaxel (Taxol) sensitivity in human renal carcinoma cell lines of different histologic types. Cancer Invest. 2000;18:614-625. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Cascinu S, Graziano F, Cardarelli N, Marcellini M, Giordani P, Menichetti ET, Catalano G. Phase II study of paclitaxel in pretreated advanced gastric cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 1998;9:307-310. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Kodera Y, Ito S, Mochizuki Y, Fujitake S, Koshikawa K, Kanyama Y, Matsui T, Kojima H, Takase T, Ohashi N. A phase II study of weekly paclitaxel as second-line chemotherapy for advanced gastric Cancer (CCOG0302 study). Anticancer Res. 2007;27:2667-2671. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Hironaka S, Ueda S, Yasui H, Nishina T, Tsuda M, Tsumura T, Sugimoto N, Shimodaira H, Tokunaga S, Moriwaki T. Randomized, open-label, phase III study comparing irinotecan with paclitaxel in patients with advanced gastric cancer without severe peritoneal metastasis after failure of prior combination chemotherapy using fluoropyrimidine plus platinum: WJOG 4007 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4438-4444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 378] [Article Influence: 31.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Futatsuki K, Wakui A, Nakao I, Sakata Y, Kambe M, Shimada Y, Yoshino M, Taguchi T, Ogawa N. [Late phase II study of irinotecan hydrochloride (CPT-11) in advanced gastric cancer. CPT-11 Gastrointestinal Cancer Study Group]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1994;21:1033-1038. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Chun JH, Kim HK, Lee JS, Choi JY, Lee HG, Yoon SM, Choi IJ, Ryu KW, Kim YW, Bae JM. Weekly irinotecan in patients with metastatic gastric cancer failing cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:8-13. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Kanat O, Evrensel T, Manavoglu O, Demiray M, Kurt E, Gonullu G, Kiyici M, Arslan M. Single-agent irinotecan as second-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer. Tumori. 2003;89:405-407. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Thuss-Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Bichev D, Deist T, Hinke A, Breithaupt K, Dogan Y, Gebauer B, Schumacher G, Reichardt P. Survival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second-line chemotherapy in gastric cancer--a randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO). Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2306-2314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kang JH, Lee SI, Lim do H, Park KW, Oh SY, Kwon HC, Hwang IG, Lee SC, Nam E, Shin DB. Salvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: a randomized phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care alone. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1513-1518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 474] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Koizumi W, Kurihara M, Nakano S, Hasegawa K. Phase II study of S-1, a novel oral derivative of 5-fluorouracil, in advanced gastric cancer. For the S-1 Cooperative Gastric Cancer Study Group. Oncology. 2000;58:191-197. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Ajani JA, Buyse M, Lichinitser M, Gorbunova V, Bodoky G, Douillard JY, Cascinu S, Heinemann V, Zaucha R, Carrato A. Combination of cisplatin/S-1 in the treatment of patients with advanced gastric or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: Results of noninferiority and safety analyses compared with cisplatin/5-fluorouracil in the First-Line Advanced Gastric Cancer Study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3616-3624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lv F, Liu X, Wang B, Guo H, Li J, Shen L, Jin M. S-1 monotherapy as second line chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer patients previously treated with cisplatin/infusional fluorouracil. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:4274-4279. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Sasaki Y, Nishina T, Yasui H, Goto M, Muro K, Tsuji A, Koizumi W, Toh Y, Hara T, Miyata Y. Phase II trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel as second-line chemotherapy for unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:812-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Koizumi W, Morita S, Sakata Y. A randomized Phase III trial of weekly or 3-weekly doses of nab-paclitaxel versus weekly doses of Cremophor-based paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric cancer (ABSOLUTE Trial). Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2015;45:303-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sym SJ, Ryu MH, Lee JL, Chang HM, Kim TW, Lee SS, Lee JS, Kang YK. Salvage chemotherapy with biweekly irinotecan, plus 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with advanced gastric cancer previously treated with fluoropyrimidine, platinum, and taxane. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31:151-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Maugeri-Saccà M, Pizzuti L, Sergi D, Barba M, Belli F, Fattoruso S, Giannarelli D, Amodio A, Boggia S, Vici P. FOLFIRI as a second-line therapy in patients with docetaxel-pretreated gastric cancer: a historical cohort. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2013;32:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kim SG, Oh SY, Kwon HC, Lee S, Kim JH, Kim SH, Kim HJ. A phase II study of irinotecan with bi-weekly, low-dose leucovorin and bolus and continuous infusion 5-fluorouracil (modified FOLFIRI) as salvage therapy for patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37:744-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Assersohn L, Brown G, Cunningham D, Ward C, Oates J, Waters JS, Hill ME, Norman AR. Phase II study of irinotecan and 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin in patients with primary refractory or relapsed advanced oesophageal and gastric carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:64-69. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Sym SJ, Hong J, Park J, Cho EK, Lee JH, Park YH, Lee WK, Chung M, Kim HS, Park SH. A randomized phase II study of biweekly irinotecan monotherapy or a combination of irinotecan plus 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin (mFOLFIRI) in patients with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma refractory to or progressive after first-line chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:481-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kim DY, Kim JH, Lee SH, Kim TY, Heo DS, Bang YJ, Kim NK. Phase II study of oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in previously platinum-treated patients with advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:383-387. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Jeong J, Jeung HC, Rha SY, Im CK, Shin SJ, Ahn JB, Noh SH, Roh JK, Chung HC. Phase II study of combination chemotherapy of 5-fluorouracil, low-dose leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FLOX regimen) in pretreated advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1135-1140. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Groenendijk FH, Bernards R. Drug resistance to targeted therapies: déjà vu all over again. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:1067-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, Lordick F, Ohtsu A, Omuro Y, Satoh T. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5541] [Cited by in RCA: 5298] [Article Influence: 353.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 43. | Gravalos C, Jimeno A. HER2 in gastric cancer: a new prognostic factor and a novel therapeutic target. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1523-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 737] [Cited by in RCA: 869] [Article Influence: 51.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 44. | Hofmann M, Stoss O, Shi D, Büttner R, van de Vijver M, Kim W, Ochiai A, Rüschoff J, Henkel T. Assessment of a HER2 scoring system for gastric cancer: results from a validation study. Histopathology. 2008;52:797-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 777] [Cited by in RCA: 868] [Article Influence: 51.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Wood ER, Truesdale AT, McDonald OB, Yuan D, Hassell A, Dickerson SH, Ellis B, Pennisi C, Horne E, Lackey K. A unique structure for epidermal growth factor receptor bound to GW572016 (Lapatinib): relationships among protein conformation, inhibitor off-rate, and receptor activity in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6652-6659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 817] [Cited by in RCA: 861] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Lorenzen S, Riera Knorrenschild J, Haag GM, Pohl M, Thuss-Patience P, Bassermann F, Helbig U, Weißinger F, Schnoy E, Becker K. Lapatinib versus lapatinib plus capecitabine as second-line treatment in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-amplified metastatic gastro-oesophageal cancer: a randomised phase II trial of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:569-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Satoh T, Xu RH, Chung HC, Sun GP, Doi T, Xu JM, Tsuji A, Omuro Y, Li J, Wang JW. Lapatinib plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel alone in the second-line treatment of HER2-amplified advanced gastric cancer in Asian populations: TyTAN--a randomized, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2039-2049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 507] [Cited by in RCA: 485] [Article Influence: 44.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Alba E, Albanell J, de la Haba J, Barnadas A, Calvo L, Sánchez-Rovira P, Ramos M, Rojo F, Burgués O, Carrasco E. Trastuzumab or lapatinib with standard chemotherapy for HER2-positive breast cancer: results from the GEICAM/2006-14 trial. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1139-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Multicenter, phase II study of trastuzumab and paclitaxel to treat HER2-positive, metastatic gastric cancer patients naive to trastuzumab (JFMC45-1102). J Clin Oncol. 2013;31 suppl:abstr 4096. |

| 50. | Ohtsu A, Shah MA, Van Cutsem E, Rha SY, Sawaki A, Park SR, Lim HY, Yamada Y, Wu J, Langer B. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3968-3976. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Okines AF, Langley RE, Thompson LC, Stenning SP, Stevenson L, Falk S, Seymour M, Coxon F, Middleton GW, Smith D. Bevacizumab with peri-operative epirubicin, cisplatin and capecitabine (ECX) in localised gastro-oesophageal adenocarcinoma: a safety report. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:702-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Fuchs CS, Tomasek J, Yong CJ, Dumitru F, Passalacqua R, Goswami C, Safran H, dos Santos LV, Aprile G, Ferry DR. Ramucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): an international, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:31-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1541] [Cited by in RCA: 1570] [Article Influence: 142.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Wilke H, Muro K, Van Cutsem E, Oh SC, Bodoky G, Shimada Y, Hironaka S, Sugimoto N, Lipatov O, Kim TY. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1224-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1613] [Cited by in RCA: 1763] [Article Influence: 160.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Cho JY. Molecular diagnosis for personalized target therapy in gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2013;13:129-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Meza-Junco J, Sawyer MB. Metastatic gastric cancer - focus on targeted therapies. Biologics. 2012;6:137-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Cutsem EV, Yeh KH, Bang YJ. Phase III trial of everolimus (EVE) in previously treated patients with advanced gastric cancer (AGC): GRANITE-1. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:(4_suppl). |

| 57. | Shimoyama R, Yasui H, Boku N, Onozawa Y, Hironaka S, Fukutomi A, Yamazaki K, Taku K, Kojima T, Machida N. Weekly paclitaxel for heavily treated advanced or recurrent gastric cancer refractory to fluorouracil, irinotecan, and cisplatin. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:206-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Lee MJ, Hwang IG, Jang JS, Choi JH, Park BB, Chang MH, Kim ST, Park SH, Kang MH, Kang JH. Outcomes of third-line docetaxel-based chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer who failed previous oxaliplatin-based and irinotecan-based chemotherapies. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:235-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Kang EJ, Im SA, Oh DY, Han SW, Kim JS, Choi IS, Kim JW, Kim YJ, Kim JH, Kim TY. Irinotecan combined with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin third-line chemotherapy after failure of fluoropyrimidine, platinum, and taxane in gastric cancer: treatment outcomes and a prognostic model to predict survival. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:581-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Li J, Qin S, Xu J, Guo W, Xiong J, Bai Y, Sun G, Yang Y, Wang L, Xu N. Apatinib for chemotherapy-refractory advanced metastatic gastric cancer: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-arm, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3219-3225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 416] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Tian S, Quan H, Xie C, Guo H, Lü F, Xu Y, Li J, Lou L. YN968D1 is a novel and selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 tyrosine kinase with potent activity in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1374-1380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Kyi C, Postow MA. Checkpoint blocking antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:368-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |