Published online Jan 7, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i1.126

Peer-review started: May 4, 2015

First decision: August 26, 2015

Revised: September 25, 2015

Accepted: November 13, 2015

Article in press: November 13, 2015

Published online: January 7, 2016

Processing time: 247 Days and 15 Hours

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) has a worldwide distribution and is endemic in many populations. Due to its unique life cycle which requires an error-prone reverse transcriptase for replication, it constantly evolves, resulting in tremendous genetic variation in the form of genotypes, sub-genotypes, and mutations. In recent years, there has been considerable research on the relationship between HBV genetic variation and HBV-related pathogenesis, which has profound implications in the natural history of HBV infection, viral detection, immune prevention, drug treatment and prognosis. In this review, we attempted to provide a brief account of the influence of HBV genotype on the pathogenesis of HBV infection and summarize our current knowledge on the effects of HBV mutations in different regions on HBV-associated pathogenesis, with an emphasis on mutations in the preS/S proteins in immune evasion, occult HBV infection and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), mutations in polymerase in relation to drug resistance, mutations in HBV core and e antigen in immune evasion, chronicalization of infection and hepatitis B-related acute-on-chronic liver failure, and finally mutations in HBV x proteins in HCC.

Core tip: Due to the unique life cycle of hepatitis B virus (HBV) which requires an error-prone reverse transcriptase for replication, it constantly evolves resulting in significant genetic variation in the form of genotype, sub-genotype, and mutations. A large number of publications on the relationship between HBV genetic variation and HBV-related pathogenesis have appeared in recent years. However, the progress in this field has not been reviewed. We have attempted to provide a brief account of the influence of HBV genotype and mutations in the different viral genome regions on HBV-associated pathogenesis. This review provides an overview for scientists working on HBV and related fields.

- Citation: Zhang ZH, Wu CC, Chen XW, Li X, Li J, Lu MJ. Genetic variation of hepatitis B virus and its significance for pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(1): 126-144

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i1/126.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i1.126

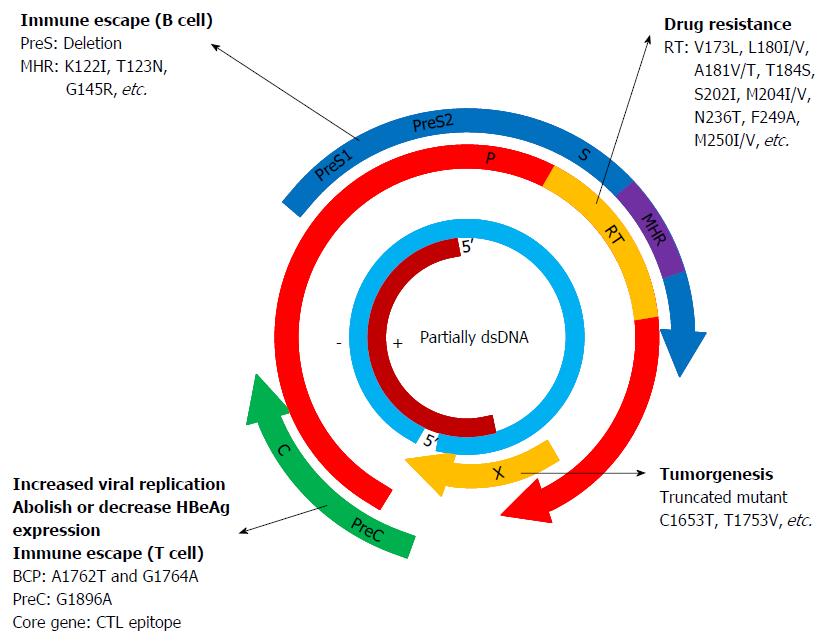

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the prototype member of a family of viruses called hepadnaviruses. It has a relaxed partially double-stranded circular DNA genome of approximately 3200 bases with four overlapping open reading frames (ORFs): pre-S/S (surface proteins), pre-C/C (pre-core/core), X (transcriptional co-activator) and P (DNA polymerase). The pre-S/S ORF is contained completely within the P ORF, but is translated in a different reading frame. ORFs C and X overlap the ORF P by 1/4 and 1/3 of their respective sequence lengths[1]. The preS/S ORF encodes three different, structurally related envelope proteins, which are synthesized from alternative initiation codons and termed Large (L), Middle (M) and Small (S) protein, respectively. The S protein [hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)] consists of 226 amino acids (aa), and the M protein has an extra N-terminal extension of 55 aa, whereas the L protein has a further N-terminal extension of 108 or 119 aa depending on the genotype. The preC/C ORF codes for two distinct products derived from in-frame alternative initiation sites on the same transcript: the core protein forming the protein shell of the nucleocapsid [hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg)] and the precore protein which is targeted into the cell’s secretary pathway, processed at both ends and eventually found in the serum of infected individuals [hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)]. The X ORF encodes the small regulatory X protein, which is essential for viral replication, and plays roles in modulating host and viral gene expression. The P ORF encodes protein P, the viral DNA polymerase[2].

HBV relies on protein P, which is also a specialized reverse transcriptase (RT), to replicate its genomic DNA via a RNA intermediate[3]. Protein P consists of four domains: a terminal protein that is covalently linked to the DNA primer during negative-strand DNA synthesis, a spacer domain that is tolerant to mutations, the RT domain, and the ribonuclease H (RNase H) domain. The RT and RNase H domains have sequences highly conserved among proteins with similar enzymatic functions such as the HIV RT[4,5]. Similar to the HIV RT, HBV RT lacks proofreading activity[6,7]. As a result, HBV exhibits an estimated mutation rate of 1.4 × 10-5-3.2 × 10-5 nucleotides per site per year, which is more than 10-fold higher than other DNA viruses[8-10]. The high error rate of HBV RT causes frequent nucleotide substitutions during viral replication, resulting in genetic diversity in the form of genotypes, sub-genotypes, quasispecies and a large number of mutations in different regions of the HBV genome. With a spontaneous error rate of 10-5 substitution/base/cycle, viral mutants are generated every day in a mixture of viral quasispecies within the same patient. These mutants usually confer disadvantages to the replication, assembly, secretion or infectivity of the virus; however, in the context of pressure due to antiviral immune response or therapy, the mutants can be selected and become the dominant species.

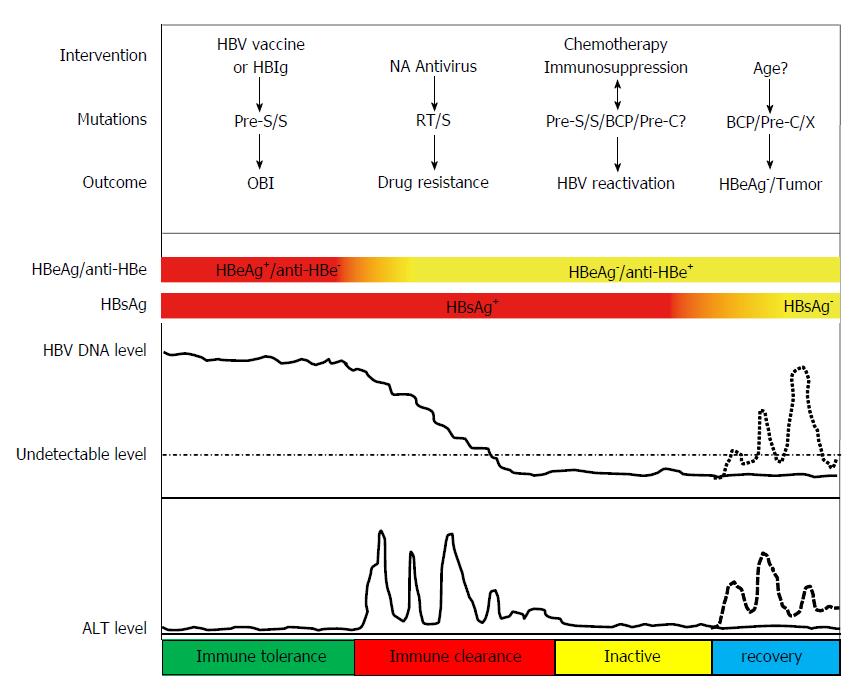

The natural history of HBV infection can vary dramatically depending on both host and viral factors. Most people do not experience any symptoms during the acute infection phase. However, some people have acute illness with symptoms that last several weeks. A small subset of people with acute hepatitis can develop acute liver failure which can lead to death. Acute HBV infection is characterized by the presence of HBsAg and immunoglobulin M antibody to the core antigen, HBcAg. During the initial phase of infection, patients are also seropositive for HBeAg. HBeAg is usually a marker of high levels of virus replication. The presence of HBeAg indicates that the blood and body fluids of the infected individual are highly contagious. In adults, about 5% of otherwise healthy persons who are infected with HBV as adults will develop chronic infection. Chronic infection is characterized by the persistence of HBsAg for at least 6 mo (with or without concurrent HBeAg). Persistence of HBsAg is the principal marker of risk for developing chronic liver disease and HCC. The 20%-30% of adults who are chronically infected will develop cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Some people can develop occult HBV infection. Occult HBV infection is defined as the presence of HBV DNA in the liver tissue of HBsAg-negative individuals[11,12].

Abundant evidence has shown that the genetic diversity of HBV plays critical roles in modulating the pathogenesis in HBV infection (Figure 1). HBV genotypes, sub-genotypes and mutations in certain regions of the HBV genome have been found to influence the HBeAg seroconversion rates, HBcAg seroconversion, viremia levels, immune escape, emergence of mutants, pathogenesis of liver disease, response and resistance to antiviral therapy, and vaccination against the virus (Figure 2).

HBV was formerly classified into nine serological subtypes according to the antigenic determinants[13]. In 1988, Okamoto et al[14] compared the full nucleotide sequence of 18 HBV strains and classified them into four groups, genotype A to D, by a divergence of more than 8% between genotypes. Since then, at least 10 genotypes (A to J) have been identified. By a divergence of 4%, HBV genotypes can be further classified into sub-genotypes. This approach has resulted in HBV genotype A (A1-A7), genotype B (B1-B9), genotype C (C1-16), genotype D (D1-D8), and genotype F (F1-F4)[15-17]. Similar to HBV serological subtypes, HBV genotypes and sub-genotypes also have distinct geographical distributions. HBV sub-genotype B1 dominates in Japan, B2 dominates in China and Vietnam, B3 is confined to Indonesia, and B4 is confined to Vietnam[18]. B7, B8, and B9 have been found in an island in Southeast Asia[19]. HBV/C1 (Cs) is found mainly in Southeast Asia, whereas C2 (Ce) is predominant in East Asia[20]. HBV/C3 was confined to Oceania, while C4 (Caus) was exclusively found in Australia and regarded as the most divergent sub-genotype within HBV/C[21]. Sub-genotypes C5 and C7 were found in Philippines, while C6 and C8 to C16 were isolated from Indonesia[22-27]. This pattern of defined geographical distribution was less evident for D1-D4, where the sub-genotypes were widely spread in Europe, Africa, and Asia[18]. Moreover, as was pointed out in a recent review article, immigration has become an important confounding factor of global HBV distribution and has been substantially changing the geographic pattern of HBV sub-genotypes[28]. Notably, the intergenotype recombination has also been described previously, which plays an important role in the evolutionary history of HBV. Recombination is favored in particular geographical regions[29,30]. For instance, B/C recombinants are prevalent in Southeast Asia and East Asia[31]. Other intergenotype recombinants such as A/D, A/E, C/D and G/C recombinants have also been observed in different geographical regions[29-31]. Therefore, it is logical to predict that distinguishing exotic (sub)genotypes from native ones will become more and more important for improved prophylaxis, diagnosis and treatment.

Not only are HBV genotypes and sub-genotypes related to geographical distribution, mounting evidence has shown that they are also associated with the pathogenesis and outcome of HBV infection. An early study from Europe found that genotype A infection was associated with a significantly higher rate of sustained biochemical remission, HBV DNA clearance, and HBsAg clearance in patients with chronic HBV infection than genotype D infection[32]. Similarly, a study from China has also shown that genotype A and B patients have a higher rate of HBsAg sero-clearance than genotype C and D patients[33]. A study from India has also suggested that genotype D was associated with more severe liver diseases and HCC in younger patients than genotype A[34]. Furthermore, a study from Alaska, where five of the ten HBV genotypes are present, showed that the rate of complications, including HCC, for those infected with genotype A appeared to be less than that found in individuals infected with genotype D, C, or F1[35]. A study by the same group also revealed that HBeAg seroconversion occurred about 3 decades later in women infected with genotype C than those infected with genotypes A2, B6, D, and F1[36]. Multiple cross-sectional studies have suggested that patients with genotype C experience HBeAg seroconversion at older ages and are more likely to be HBeAg positive at any given age than HBV genotype B[37-39]. HBV genotype C has also been associated with increased risk of liver inflammation, flares of hepatitis, liver fibrosis, and cirrhosis[37,38,40]. Prospective studies compared the outcome in those infected with genotypes B and C further and have also shown that HBeAg seroconversion occurred at a significantly younger age for those infected with genotype B than genotype C[36,41-43], and that increased risk of fibrosis was associated with genotype C[42,44]. In addition, infection with genotype C has been identified as an independent risk factor for the development of HCC[45]. Taken together, it can be concluded that individuals infected with HBV genotype C seroconvert from HBeAg later in life and have an increased risk of liver inflammation, liver fibrosis, and HCC. In an acute liver failure study in the United States, genotype D was found to be an independent risk factor for fulminant hepatitis[46]. Genotype G is the most uncommon of all HBV genotypes. This genotype is almost exclusively found in persons co-infected with another HBV genotype, most commonly genotype A, with the only exception being a single report of a transfusion-associated case[47,48]. HBV genotypes F and H are the ‘‘New World’’ genotypes found primarily in indigenous populations of North and South America. In a nested case-control study of a cohort of 1176 Alaskan Natives with chronic HBV infection followed up for 20 years, a significantly higher proportion of persons infected with either genotype F1 or genotype C2 developed HCC than those infected with genotype A2, B6, or D[35]. Genotype H is most closely related to genotype F and likely evolved from this genotype.

The current definitive method for HBV genotyping is PCR amplification and sequencing of the entire genome followed by phylogenetic analysis[14,49-51]. Studies on HBV concerning different genotypes frequently face problems regarding representativeness of reference strains. Taking advantage of large number of sequences deposited in the GenBank database, we have developed a strategy to establish reference sequences for different genotypes. Briefly, sequences were clustered and genotyped using phylogenetic analyses first, and sequences belonging to the same genotype were then aligned with each other and the most common nucleotides in each position were chosen to form the reference sequence for this particular genotype[52]. Although HBV consensus sequences can be generated by sequence alignment, they may not exist in nature or can not usually be isolated from patient samples. To solve this problem, we have adopted a chemical synthesis strategy to generate the consensus HBV genome for certain genotypes. In our recent study, genotype B consensus sequence was established by comparing 42 full-length HBV genotype B sequences and the genome was generated by chemical synthesis. A plasmid carrying a 1.3 × full-length chemically synthesized HBV consensus genome was constructed. This consensus genome was fully replication competent when transfected into hepatoma cells. After this plasmid was hydrodynamically injected into BALB/c mice, HBsAg, anti-HBs, HBeAg, anti-HBe, anti-HBc and HBV genome replication were all detected. Thus, this approach represents a novel strategy to design and create HBV genomes for future studies[53].

The preS/S ORF encodes proteins L, M and S. The Pre-S1 domain is unique for the L protein. The Pre-S2 domain is the shared sequence with the M protein and the S domain is seen in all three proteins. The L and S proteins are essential for virion formation and the M protein can increase the efficiency of virion secretion[8,54,55]. The dominant epitopes of HBsAg, which are the targets of neutralizing B cell responses, are located in the “α” determinant (aa 124-147) within the HBsAg major hydrophilic region (MHR), which covers aa 99-169[56-62]. Mutations in the MHR, particularly the ‘‘a’’ determinant, are known to be associated with immune escape due to conformational changes in the epitope resulting in reduced binding affinity between the HBsAg and the antibody to HBsAg. Carman et al[56] first reported the G145R mutation in the ‘‘a’’ determinant of HBsAg in a child who became infected with HBV despite active and passive immunoprophylaxis. Subsequently, several other mutations within and outside the “α” determinant were reported to have reduced binding affinity to anti-HBs[57,63,64]. To date, escape mutations in the HBsAg MHR have been comprehensively analyzed[65-67].

In 2003, we noted that a renal transplant recipient was persistently positive for HBV despite preexisting anti-hepatitis B surface antibodies (anti-HBs). We cloned the HBsAg gene that was found to be mutated from the patient and compared the antigenicity and immunogenicity of the mutant HBsAg with wild-type HBsAg (wtHBsAg) in mice using a genetic vaccination approach. Our results showed that both B cell and T cell immune responses were impaired by these mutations, suggesting that mutations within HBsAg may enable HBV to escape immunological control[68]. Subsequently, in an agenetic vaccination animal model, we demonstrated that serum samples from mice immunized with aa substitution G145R could recognize plasma-derived mtHBsAg, suggesting HBsAg with aa substitutions may be immunogenic, but with changed specificity[69]. We further investigated the impact of some naturally occurring HBsAg mutations around position 120 to 123 on the antigenicity and detection of HBsAg. Strikingly, aa substitution K122I abolished the reactivity of HBsAg in all immunoassays tested. mtHBsAg G145R was clearly detected with four different enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays that were based on monoclonal anti-HBs antibodies (MAbs) with high affinity. Positive immunofluorescence staining of mtHBsAg K122I was achieved only by polyclonal anti-HBs, while all tests using MAbs failed. mtHBsAg T123N showed a low reactivity in immunoassays and appeared to be secretion deficient. The aa substitution P120T reduced the binding of anti-HBs, but did not completely prevent the detection of mtHBsAg by anti-HBs MAbs. Thus, our data showed that the presence of aa substitutions within the region of 120 to 123 is essential for HBsAg antigenicity and strongly associated with impaired detection in immunoassays[70]. In another study, we systematically investigated a variety of aa substitutions that have been identified around or within the “α” determinant of HBsAg, such as K122I and G145R, on HBsAg expression, secretion and antibody binding. The results showed that the hydrophobicity, the presence of the phenyl group, and the charges in the side chain of the aa residues at position 145 reduced HBsAg secretion and impaired reactivity with anti-HBs antibodies. Only the substitution K122I at position 122 affected HBsAg secretion and recognition by anti-HBs antibodies. Genetic immunization in mice further demonstrated that the priming of anti-HBs antibody response was strongly impaired by the substitutions K122I, G145R, and others, such as G145I, G145W, and G145E. Moreover, when mice that had been pre-immunized with wtHBsAg or variant HBsAg (vtHBsAg) were challenged by hydrodynamic injection (HI) with a replication-competent HBV clone, HBsAg persisted in peripheral blood for at least 3 d after HI in mice pre-immunized with vtHBsAg, but was undetectable in mice pre-immunized with wtHBsAg, indicating that vtHBsAgs fail to induce proper immune responses for efficient HBsAg clearance. Therefore, the biochemical properties of aa residues at positions 122 and 145 of HBsAg have a major effect on antigenicity and immunogenicity. In addition, the presence of proper anti-HBs antibodies is essential for the neutralization and clearance of HBsAg during HBV infection[71].

Viral envelope N-glycosylation modification has been known to play important roles in the biogenesis, stability, antigenicity and infectivity in HIV, HCV and influenza virus[72,73]. Previously, a few studies indicated that a potential N-glycosylation site (Asn-X-Ser/Thr, where X is any aa except Pro) could be created by some mutations within the HBsAg MHR[62,74]. In a recent study, we systematically examined the effects of naturally occurring N-glycosylation-related aa substitutions K122I, T123N, A159G and K160N. T123N and K160N substitutions resulted in additional N-glycosylated forms of HBsAg, while the other mutations produced more heavily glycosylated HBsAg compared with the wild-type (wt). These results showed that vtHBsAg with K122I could not be recognized by HBsAg immunoassays, ELISA or immunofluorescence staining, vtHBsAg with T123N, A159G, K160N and A159G/K160N could be detected, but showed reduced antigenicity. DNA immunization in BALB/c mice revealed that wtHBsAg and vtHBsAg with T123N and K160N were able to induce antibodies to HBsAg (anti-HBs), whereas K122I and A159G greatly impaired the ability of HBsAg to trigger anti-HBs responses. The cellular immune response to the HBsAg aa 29-38 epitope was enhanced by the K160N substitution. Replication competent clones of HBV, T123N and A159G substitutions were shown to strongly reduce virion assembly. The aa substitution K160N appeared to compensate for the negative effect of A159G on virion production. Thus, our study revealed complex effects of aa substitutions on the biochemical properties of HBsAg, on antigenicity and immunogenicity, and on the replication of HBV[75]. Another recent study investigated the molecular and clinical characteristics of HBV immune escape mutants in a Chinese cohort of chronically infected patients. By investigating 216 patients with double positive HBsAg and anti-HBs and 182 HBV carriers without anti-HBs as a control group, the authors found that the frequency of N-glycosylation mutations in the patient group was much higher than that in the control group (47/216 vs 1/182). Using a chemiluminescent microparticle enzyme immunoassay, they showed that HBsAg mutants reacted weakly with anti-HBs compared with wtHBsAg. Their native gel analysis of secreted virion in supernatants of transfected Huh7 cells further revealed that mutants had better virion envelopment and secretion capacity than wt HBV[76]. Together these studies strongly suggested that N-glycosylation mutations on HBsAg greatly contribute to immune escape.

Numerous studies including ours have demonstrated that immune escape mutations were the underlying mechanisms for HBsAg and anti-HBs double positive status[60,77,78]. These mutations are also responsible for a large portion of failure in immunoprophylaxis. In Taiwan, the prevalence of surface gene mutants was found to be approximately 20% in HBsAg carrier children[79]. A study from China reported that the prevalence of aa substitutions among immunoprophylaxis failed children was 20%[80]. Another study reported that the nucleotide diversity rate was 11.4% in those children in Jiangsu Province[81]. The mutation rate in children who failed to be protected by perinatal prophylaxis in Singapore, Japan, and the United States has been reported to be 39.0%, 30.8% and 25.5%, respectively[64,82,83].

Variants within the MHR of HBsAg have also been associated with occult HBV infection (OBI). A study from China by Hou et al[84] found that in 46 cases of OBI, 32 aa substitutions were found between positions 100-160 within the MHR. In addition to the G145R, 11 positions inside and 5 positions outside the “α” determinant were involved. Combined mutations were also detected in some patients. Another two patients had insertion mutations immediately before the “α” determinant. Another study conducted in China in recent years identified another 8 escape mutations associated with OBI, in addition to the G145R, mainly located at positions 120, 126, 129, 130, 133, 134, 137, 140, 143 and 144[66]. In a recent cohort study conducted in South Korea, mutations in the “α” determinant were also found to be related to OBI[85]. Another recent study from China compared the characteristics of 61 patients with OBI to 153 HBsAg (+) carriers with low titers of serum HBsAg (HBsAg-L group) and 54 samples with high serum HBsAg (HBsAg-H group). MHR mutations were seen significantly more frequently in OBI cases (55.7%) compared to the HBsAg-L (34.0%) or the HBsAg-H groups (17.1%). 13 representative MHR mutations were observed in patients with OBI. Of which, 4 mutations strongly decreased the analytical sensitivity of 7 commercial HBsAg immunoassays and 10 mutations significantly impaired virion and/or S protein secretion in both Huh7 cells and mice[86].

Mutations in the pre-S region, especially deletions, have been associated with a lack of detectable HBsAg in the serum. Deletions in the pre-S region can result in reduced expression of HBV surface proteins and help viral persistence by eliminating HLA-restricted B-cell and T-cell epitopes. Pre-S1/pre-S2 mutations are also frequently detected in OBI[85,87,88]. In one study, a 183-bp deletion (nt 3019 to 3201) in the pre-S1 region was detected in occult HBV patients. The deletion covered the CCAAT element that is required for transcription factor binding. The association of deletions in the pre-S gene with a lack of secreted HBsAg was demonstrated using functional analysis by transfection into hepatocyte cell lines[89]. In a similar study, Xu et al[90] showed that a 129-bp in-frame deletion in the S promoter region was associated with reduced levels of M and S protein transcripts, resulting in a marked reduction in the expression of the two proteins. The roles of S promoter mutations and deletions in HBsAg production and secretion in OBI have also been reported in other studies[87,91]. In a recent study, a male patient from China with a chronic hepatitis B infection for 30 years was diagnosed with HB-LF. We amplified the HBV sequences from this patient and found that 2 major variants coexisted in the ratio of 1 to 4: the first variant harbored the A1762T/G1764A 257 double mutation in the basal core promoter (BCP) region and the G1896A mutation in the preC region; the second variant contained 2 deletions in the preS1 region (nt 2976-3102) and the preS2 promoter and preS2 ORF region (nt 3203-3215, nt 1-31), resulting in a stop codon mutation in the ORF of large HBsAg and the deletion of the start codon in the ORF of middle HBsAg, respectively. When we transfected replication competent plasmids harboring these variants into Huh7 cells, we observed phenotypes one would normally predict. However, when both constructs were co-transfected into Huh7 cells, new phenotypes arose. For example, coexistence of both variants increased HBV replication and led to the predominant nuclear localization of HBcAg. Moreover, mice mounted significantly stronger antibody and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses to HBsAg when both variants were co-applied in the HI mouse model. Thus, the coexistence of preS deletion mutants with other variants may significantly modulate specific host immune responses and may enhance immune-mediated liver damage under some circumstances, which represents a novel mechanism for the immunopathogenesis of HBV infection[92].

Numerous studies have linked preS, especially preS2 deletions to the occurrence of HCC[93-98]. At least three mechanisms have been suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of preS deletion-associated HCC: Firstly, the preS1 and preS2 regions contain several epitopes for T and B cells, and play essential roles in the interaction with host immune responses. Therefore, preS deletion mutations may result in an inefficient immune response[99,100]. Secondly, pre-S1 and pre-S2 mutations may cause overproduction and accumulation of L protein in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), resulting in significant ER stress that may induce DNA damage and genomic instability leading to hepatocarcinogenesis[101]. Thirdly, preS2 mutants have been shown to directly activate tumor promoting pathways such as the VEGF/AKT/mTOR pathway and the p27/retinoblastoma/Cdk2/cyclin A, D pathway, among others[102-106]. In fact, the pre-S mutants have been shown to be capable of inducing dysplasia in hepatocytes and the development of HCC in transgenic mice[107].

S region mutations have also been associated with acute exacerbation of liver diseases leading to fatal liver failure. In our study, a Chinese patient who suffered from acute liver failure after discontinuation of lamivudine treatment was described. The patient was treated with lamivudine for 4 mo and ceased treatment without consulting. After receiving lamivudine, the patient developed anti-HBs and became negative for hepatitis B surface antigens (HBsAg). However, the patient suffered from a severe exacerbation about two months after cessation of treatment and died due to acute liver failure. Sequencing of HBV isolates revealed mutations including G145R and stop codon mutations at the aa positions 74 and 199 in the HBsAg sequences in all clones. F134S and F134V substitutions within the a-determinant were also detected in some clones. Various aa substitutions were present outside the a-determinant. No wt clone was found among the six cloned sequences. Importantly, no lamivudine resistance-associated mutation was found in the RT region coding for the HBV polymerase protein. The data suggested that anti-HBs antibody which appeared during the lamivudine treatment might be the selective force for the emergence of HBV mutants, and HBV replication resumed after the cessation of lamivudine treatment in this patient might have triggered the process leading to liver failure[108].

In a recently published study, a correlation was revealed between some HBsAg-mutations and serum HBV-DNA levels in HBV chronically-infected drug-naive patients. In this study, 187 patients were stratified into the following ranges of serum HBV-DNA: 12-2000 IU/mL, 2000-100000 IU/mL, and > 100000 IU/mL. The S gene of HBV was isolated and sequenced. Mutant and wt HBV genomes were expressed in Huh7 cells and HBsAg production was determined in cell-supernatants 3 d post-transfection. The results showed that HBsAg-mutations M197T, S204N, Y206C/H and F220L were significantly correlated with serum HBV-DNA < 2000 IU/mL (posterior-probability > 90%, P < 0.05), and the presence of Y206C/H and/or F220L was also associated with lower median (IQR) HBsAg-levels and lower median (IQR) transaminases [for HBsAg: 250 (115-840) IU/mL for Y206C/H and/or F220L vs 4300 (640-11838) IU/mL for wt, P = 0.023; for ALT: 28 (21-40) IU/mL vs 53 (34-90) IU/mL, P < 0.001). These mutations were localized in the HBsAg C-terminus, known to be involved in virion and/or HBsAg secretion. Thus, specific HBsAg-mutations in the HBsAg C-terminus correlated with low-serum HBV-DNA and HBsAg-levels. These mutations may represent an important mechanism underlying low HBV replication and the inactive-carrier state[109].

The P ORF encodes the viral DNA polymerase protein P, which is a specialized RT. Except for interferon-α and pegylated interferon-α, all five drugs approved for HBV treatment are nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) that target the DNA polymerase activity of this protein. Treatment with these NAs is generally efficient and well tolerated. However, resistance to some of these agents is a major issue affecting long-term therapy. Lamivudine resistance occurs frequently and is observed in up to 80% of patients treated for 5 years[110-112]. Among adefovir-treated patients, the cumulative incidence of resistance over 5 years has been reported to be 29% in HBeAg-negative patients and 42% in HBeAg-positive patients[113,114]. With 25% of HBeAg-positive and 11% of HBeAg-negative patients experiencing virological breakthrough due to resistance after 2 years of treatment, telbivudine resistance is relatively slower to emerge[115]. Resistance to entecavir has been shown to remain low (1.2%) after 6 years of therapy in NA-naıve patients[116]. No tenofovir resistance has been observed after 4 years of treatment in the registration studies[117].

Antiviral drug resistance is associated with the selection of adaptive mutations which reduces the sensitivity of the mutants to the inhibitory effects of a drug. The barrier to resistance can be defined as the difficulty with which the resistance mutants are selected and the barrier to resistance increases as the number of specific mutations required for drug resistance increase[118]. The main aa change associated with lamivudine and telbivudine-resistance is rtM204V/I, which is located in the YMDD motif of the RT. In the context of lamivudine resistance, the compensatory mutations rtL180M and rtV173L frequently occur in domain B and C of the viral polymerase[4]. The rtA181V/T, rtL80I/V and rtM204Q mutants identified recently showed that primary lamivudine-resistance mutations can also occur outside the YMDD motif[119,120]. Lamivudine-resistance mutations have been reported to result in the selection of high replicative HBV variants leading to exacerbation of disease during chronic HBV infections. In an early study, full-length HBV genomes were analyzed from four chronic hepatitis B patients who developed resistance to lamivudine [-2’-deoxy-3’-thiacytidine, LMV] accompanied by acute exacerbation of disease. Paired full-length HBV isolates were cloned from the sera of patients prior to LMV treatment and after drug resistant breakthrough. Compared to the isolates before treatment, isolates from all four patients during exacerbation showed a marked increase in replicative competence in a cell transfection study. Viral genome amplification and sequencing showed that while all isolates shared mutations at the YMDD motif, the isolates from the one patient who recovered from the exacerbation showed a lower number of mutations, and in particular, lacked BCP mutations at 1762/1764. In contrast, BCP mutations were found in isolates from the other three patients. Thus, in patients with acute exacerbation, high replicative strains were selected from the total HBV quasispecies during treatment, and among these strains, those with core promoter mutations at 1762/1764 were most likely to be associated with severe clinical exacerbations[121]. Adefovir resistance is characterized by rtN236T and/or rt181V/T selected in the D and B domain of the polymerase, respectively[122-124]. The rtI233V mutation was found to confer resistance to adefovir[124]. Entecavir is a NA with a high barrier of resistance as multiple mutations are required to confer a high level of resistance to this drug. Entecavir resistance tends to emerge in a stepwise manner with the rtI169T, rtT184S, rtS202I, and rtM250I/V changes occurring sequentially in the virus already carrying lamivudine resistance mutations[125,126].

No tenofovir resistance has been described after 3 and 4 years of therapy, but rt181T/V and rtN236T, the main adefovir-associated resistance mutations, do reduce its sensitivity clinically and virologically[117,122,127]. Tenofovir (TDF) has been a first-line antiretroviral drug for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) since 2001 and it is well known that this drug induces resistance mutations leading to treatment failure. Taking advantages of the high homology between the HIV and HBV RTs and the determination of the crystal structure of HIV-1 RT complexed with TDF, we built the homology model for HBV-RT[5,128]. Based on the modeled HBV-RT structure, we designed some mutants and tested their effects on TDF susceptibility in vitro in Huh7 cells and in vivo in a mouse model. Our results showed that HBV mutants with rtP177G and rtF249A reduced susceptibility to tenofovir in vitro with a resistance index of 2.53 and 12.16, respectively, and the testing result based on the HI mouse model revealed the antiviral effect of TDF against wt and mutated HBV genomes, and confirmed the reduced susceptibility of mutant HBV to TDF[129]. In a recent population-based cross-sectional study from China, serum samples from 179 patients who developed virological breakthrough while receiving treatment with NAs were obtained and analyzed for NA-resistant mutations in the RT region[130]. NA-resistant mutations were detected in 89.4% (160/179) of these patients. The prevalence of HBV mutations at rtM204 was 93.0% (106/114) in patients on lamivudine/telbivudine-based therapy, with rtM204I being more frequently associated with rtL80I/V mutations [rtM204I + rtL80I/V (50.0%, 32/64) vs rtM204V + rtL80I/V (27.3%, 9/33), P = 0.032]; rtN236 mutations were found in 76.1% (35/46) of patients receiving adefovir/dipivoxil-based therapies, with rtM204V mutations being more frequently associated with the rtL180M mutations [rtM204V + rtL180M (100%, 33/33) vs rtM204I + rtL180M (60.9%, 39/64), P < 0.001]. In addition, rtA181 mutations were observed in 19.3% (22/114) of patients receiving lamivudine/telbivudine-based therapy and 23.9% (11/46) of patients receiving adefovir/dipivoxil-based therapy.

The RT and HBsAg ORFs overlap at RT aa 8-236, and the HBsAg ORF shifts downstream by 1 nucleotide. Not surprisingly, some resistance mutations also affect the overlapping HBsAg. For instance, the rtA181T mutant selected by adefovir, lamivudine or telbivudine typically results in a stop codon in the envelope gene (sW172stop), causing a dominant negative secretion defect in HBsAg leading to an altered viral rebound profile[131]. Studies have also shown that common antiviral drug selected mutations may confer changes in the antigenicity of the overlapping HBsAg. A pioneering study by Torresi et al[132] reported that resistance mutations rtV173L + rtL180M + rtM204V that resulted in mutations sE164D + sI195M in HBsAg reduced antigen-antibody binding. A few years later, Sloan et al[133] confirmed their observations and further revealed that these mutations caused immune evasion through disruption of the “α” determinant on HBsAg. In recent years, similar observations have been made in studies from Brazil and China[134,135]. On the other hand, the overlapping changes in surface genes may potentially affect the impact of HBV polymerase mutation on replication and drug resistance. For example, the sW172 stop mutation could result in decreased viral replication and increased drug resistance[136,137]. Additionally, wt HBV and drug-resistant HBV such as the sW172 stop mutation could complement each other to maintain viral replication and rescue virion production under NAs treatment, thus facilitating HBV survival and persistence under NAs pressure (our unpublished data).

The HBV core gene is divided into the precore (PC) region and the basic core region (BCP) by two in-frame initiating ATG codons. This results in the transcription of either the pregenomic RNA that is essential for HBV replication and translates into the nucleocapsid protein HBcAg or the PC RNA that translates into HBV e antigen (HBeAg) protein. Studies have linked defect core protein expression to PC and/or BCP mutations. The most prevalent PC mutation is a guanine-to-adenine transition at nucleotide position 1896 (G1896A), which creates a TAG stop codon at codon 28 of the PC protein and abolishes HBeAg expression at the translational level[138]. The most common BCP mutation is the double A1762T and G1764A nucleotide exchange, which results in a decrease in HBeAg expression of up to 70%, but enhanced viral genome replication[138-140].

The core protein HBcAg of HBV is a potent immune stimulator, stimulating a strong neutralizing immune response[141,142]. Cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) play a key role in the control of HBV infection and viral clearance. The HBV-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes (CTL)-mediated immune response is multi-specific, polyclonal, and vigorous during acute hepatitis B (AHB), which plays a vital role in viral control and viral clearance, as well as disease pathogenesis[143-145]. In contrast, the HBV-specific CTL response is minimal or undetectable in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) with viral persistence and immune tolerance, indicating the key role of HBV-specific T-cell response in the determination of disease progression and outcome[146,147]. Analysis of CTLs specific for viral epitopes within core, envelope, polymerase, and X proteins showed that the highly conserved HBV core protein (HBc) elicits the strongest CTL responses compared with other viral proteins, suggesting that the HBc-specific T cell response may play a leading role in viral control and clearance[148-152]. However, mutations in HBcAg may lead to the production of immune escape variants, resulting in the persistence of HBV[2,153]. In a recent study, the HBV core gene was amplified and sequenced from 148 patients with chronic HBV infection, and the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I genotype (A and B loci) of the patients was determined. Using a statistical approach with a novel analysis package SeqFeatR, residues under selection pressure in the presence of particular HLA class I alleles were identified. With this approach, nine residues in HBV core under selection pressure in the presence of 10 different HLA class I alleles were identified. Immunological experiments confirmed that seven of these residues were located inside epitopes targeted by patients with chronic HBV infection carrying the relevant HLA class I allele. Consistent with viral escape, the selected substitutions reproducibly impaired recognition by HBV-specific CD8 T cells[154].

HBeAg is not required for HBV replication in vitro, but is secreted into the blood. Acting as both an immunogen and a tolerogen, it has profound effects on the natural history and pathogenesis of HBV infection[155]. In general, HBV replicates more actively in carriers with HBeAg than those with anti-HBe, and carriers with HBeAg have a higher activity to transmit HBV than those with anti-HBe[156]. In chronic hepatitis B infection, a key event in the natural history of progression is HBeAg seroconversion to HBeAb with a marked reduction of HBV replication followed by gradual histological improvement[157]. However, a proportion of patients who undergo HBeAg seroconversion demonstrate a recurrence of high HBV DNA levels and intermittent or persistent ALT level elevations. These individuals harbor a mutant form of HBV that does not produce HBeAg, due to a mutation in the precore or core promoter region. In Asia, the Middle East, Mediterranean basin and southern Europe, about 15% to 20% of these carriers have elevated alanine aminotransferase and viral DNA[158]. HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B (precore mutant) emerges as the predominant species during the course of typical HBV infection with wt virus and is selected during the immune clearance phase (HBeAg seroconversion)[159]. Sustained spontaneous remission is rare (6% to 15%) in these individuals, and spontaneous HBsAg clearance is only about 0.5% per year[160]. Therefore, long-term prognosis is poorer among HBeAg-negative individuals than their HBeAg-positive counterparts. In fact, HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B is currently the main type worldwide as well as the most difficult to treat in terms of achieving sustained virological response.

In China, hepatitis B-related ACLF (HB-ACLF) patients account for more than 80% of ACLF cases as a result of the high incidence of chronic HBV infection, with a high mortality rate of 60%-80% in the absence of liver transplantation, causing 22600 deaths annually[161,162]. Characterized by increased viral load and a fierce immune response, HB-ACLF is very often associated with mutations in the BCP and PC regions, because the BCP mutations may enhance HBV replication and the PC mutation abrogates translation of HBeAg, which is considered a tolerogen and immune repressor buffering the immune attack on the infected hepatocyte[163-168]. In fact, a higher prevalence of the BCP double mutation A1762T/G1764A and the G1896A PC mutation have been reported in ALF than in acute hepatitis B patients[169-173]. In addition, single mutations including the T1753V (C/A/G), C1766T, T1768A, G1862T and G1899A in the BCP/PC region have been reported to be associated with increased HBV replication capacity and/or reduced HBeAg expression in vitro, and in some cases associated with ALF in the clinic[46,163,173-176]. A recent study reported that T1846 and A/G1913 mutations are associated with ACLF in patients infected with HBV genotypes B and C[177].

Chronic HBV infection is the dominant global cause of HCC, accounting for 55% of cases worldwide and 80% or more in the eastern Pacific region and sub-Saharan Africa[178]. Accumulating evidence has shown that HBxAg, the viral product of the X ORF, plays critical roles in the pathogenesis of HCC[179]. HBxAg promotes carcinogenesis by interacting with cellular proteins resulting in dysregulation of multiple signaling pathways involved in cell cycle progression, cell growth and apoptosis. To date HBxAg has been found to interfere with cellular signaling pathways including Src, pRb/E2F, p53, NF-κB, PI3K, Jak1/STAT, ERK and PI3K/AKT and Wnt/β-catenin[180-187]. During the last decade or so, several studies have indicated that the C-end truncated X protein often occurs in patients with HCC[188-194]. Further investigations revealed that the truncated HBxAg lost the proapoptotic activity of the full length form and thus acquired stronger cellular transformation activity in vitro and tumor promoting activity in vivo[189]. A recent study reported that, relative to WTHBxAg, naturally occurring truncated mutant HBxΔ127 strongly enhanced cell proliferation and migration in HCC[195]. In addition to truncated HBxAg mutants, insertions in the HBx gene may play a pivotal role in hepatocarcinogenesis. A Korean cohort study showed that the prevalence of insertions was significantly higher in patients with severe liver disease, HCC, or cirrhosis of the liver compared to patients who were carriers or had chronic hepatitis. Four novel types of insertions including PKLL, GM, FFN, and tt, were observed in six patients, which were accompanied by double mutations in the BCP region[196]. Moreover, site mutations have also been associated with HCC. Studies from Korea have reported that HCC risk increased in the presence of ≥ 6 mutations of eight key mutations in Korean chronic HBV genotype C2 carriers. The eight key mutations comprise G1613A, C1653T, T1753V, A1762T, G1764A, A1846T, G1896A and G1899A that are located throughout the core promoter and the proximal portion of the precore gene (X/preC region)[197,198]. A recent study assessed the postoperative prognostic value of HBV mutations in HBxAg in HBV associated HCC patients and found that eight mutational sites, including 1383, 1461, 1485, 1544, 1613, 1653, 1719, and 1753, could serve as independent predictors of HCC survival[199].

Reactivation of HBV infection is a well-documented complication among cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. In recent years, it has become clear that HBV mutations associated with severe liver diseases are frequently found in patients on chemotherapy. The most common mutations associated with chemotherapy-related HBV reactivation include the G to A mutation at nt 1896 in the preC/C region, the nt 1762 (A to T) and nt 1764 (G to A) mutations in the preC promoter region[200-204]. A study of ours suggested that immune escape mutations may also be involved in chemotherapy-associated HBV reactivation[205].

HBV reactivation can also occur during immunosuppression. A few years ago, we reported a case in which a non-Hodgkin lymphoma patient who had displayed positive anti-HBs and anti-HBc before immunosuppressive therapy developed HBV reactivation after receiving a rituximab-based regimen. Our sequencing data revealed genotype D with two known escape mutations P120S and S145P and three other mutations Y134K, I150T and T189I, which had not been found in the usual escape setting[206]. In a recent study, the genetic features of HBsAg were investigated by population-based and ultradeep sequencing (UDS) of HBV DNA from 93 patients: 29 developed HBV reactivation and 64 consecutive patients with chronic HBV infection (as controls)[207]. Of the HBV-reactivated patients, 51.7% were treated with rituximab, 34.5% with different chemotherapeutics, and 13.8% with corticosteroids only for inflammatory diseases. In total, 75.9% of HBV-reactivated patients (vs 3.1% of control patients; P < 0.001) carried HBsAg mutations localized in immune-active HBsAg regions. Of the 13 HBsAg mutations found in these patients, 8 of 13 (M103I-L109I-T118K-P120A-Y134H-S143L-D144E-S171F) reside in the MHR where neutralizing antibodies target. The remaining five (C48G-V96A-L175S-G185E-V190A) are localized in class I/II-restricted T-cell epitopes, suggesting a role in HBV escape from T-cell-mediated responses. Using UDS, these mutations occurred in HBV-reactivated patients with a median intra-patient prevalence of 73.3% (range, 27.6%-100%) vs 4.6% (range, 2.5%-11.3%; P < 0.001) in control patients, supporting their fixation in the viral population as a predominant species. Moreover, additional N-linked glycosylation sites within the MHR were found in 24.1% of HBV-reactivated patients (vs 0% of chronic patients; P < 0.001). Thus, data from this study suggest that HBV reactivation occurs upon immunosuppression, correlating with HBsAg mutations endowed with enhanced capability to evade immune response. Another study cloned and sequenced the full length HBV genome from an HBsAg-negative patient who developed HBV reactivation following chemotherapy with rituximab[208]. The results showed that the number of aa substitutions in HBV from this patient was much higher than that reported for occult HBV infection or vaccine escape. It is worth noting that this study detected not only known “α” determinant mutations such as Q129H, F134Y, D144E and the preC G1896A mutation, but also a large number of mutations in other regions including preS, P, X and C, suggesting the possibility that mutations in other regions may also play some roles in immunosuppression-associated HBV reactivation.

Co-infection with HBV and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is not uncommon. It is estimated by the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS that 10% of 33 million HIV-infected patients has concurrent chronic HBV infection[209]. A higher proportion of chronic HBs antigenemia has been found in HIV-infected patients because HIV destroys CD4 cells which compromises host immunity against HBV[210]. Clinical observational studies have demonstrated that HIV/HBV-co-infected patients may have faster progression of hepatic fibrosis and a higher risk of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and HCC than HBV-mono-infected patients[211,212]. The recurrence of HBV replication due to withdrawal of lamivudine therapy and administration of glucocorticosteroids in HIV/HBV-co-infected patients has been described previously[213-216]. Further observations including ours revealed that even slight suppression of host immunity by HIV infection at a level that did not require drug therapy could cause HBV reactivation[217,218]. It is worth noting that immune escape mutations were detected in most of these studies.

Most HBV genotypes and sub-genotypes have distinct geographical distributions. Abundant evidence has shown that genotypes and sub-genotypes are associated with the pathogenesis and outcome of HBV infection. Generally, HBV genotype C has been associated with an increased risk of liver inflammation, flares of hepatitis, liver fibrosis and HCC. Compared to other genotypes, patients with genotypes D, C, and F1 are more likely to develop complications such as liver cirrhosis and HCC. In addition, HBeAg seroconversion occurred much later in patients infected with genotype C compared to other genotypes. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, mutations in the preS/S region are associated with vaccine failure, immune escape, occult HBV infection and the occurrence of HCC. Mutations in the P region may cause drug resistance to NA antivirals. Mutations in the preC/C region are related to HBeAg negativity, immune escape, and persistent hepatitis. Mutations in the X region play critical roles in promoting HCC.

Investigations of HBV genetic variability and pathogenic implications of specific mutations have resulted in significant advances over the past decade. A significant increase in the body of knowledge regarding HBV genetic variability has greatly improved the way HBV infection is managed and treated. However, there are questions that remain unanswered and obstacles that need to be overcome. For example, much of our current understanding regarding HBV genetic variability was inferred from molecular epidemiological analyses. Due to constant viral evolution as a result of interactions among the host, virus and drug therapy, the results of these types of analyses can be confounded by many known or unknown factors. We believe that more physical experiments using reference strains that are really representative of their respective genotypes and sub-genotypes can help overcome this problem and provide more detailed and reliable information. In addition, as both viral and host factors affect HBV pathogenesis, reliable biomarkers and convenient methods need to be established to monitor both the viral and host factors to, ideally, achieve personalized management and treatment. As an example, in a recent pioneering study, Gong et al[219] compared the performance of next-generation sequencing and clone-based sequencing (CBS) in analyzing HBV RT quasispecies heterogeneity. In that study, HBV genomic DNA was extracted from serum samples obtained from 31 antiviral treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B. The RT region quasispecies were analyzed in parallel using CBS and ultradeep pyrosequencing (UDPS). Their data showed that the number of qualified strains obtained by UDPS was much larger than that obtained by CBS (P < 0.001), and the complexity value derived from UDPS data was higher than that derived from CBS data (P < 0.001). A study on the prevalence of variations within the RT region showed that CBS detected an average of 9.7 ± 1.1 aa substitutions/sample and UDPS detected an average of 16.2 ± 1.4 aa substitutions/sample. This study clearly demonstrated that viral heterogeneity determination by the UDPS technique is more sensitive and efficient in detecting low-abundance variations than that by the CBS method, and thus has shed some light on the future clinical application of next generation sequencing in HBV quasispecies evaluation[219]. Additionally, it is important to continue research on the identification of novel therapeutic targets in the life cycle of HBV or in the host immune system to stimulate the development of new antiviral agents and immunotherapies. These can be antiviral agents targeting HBV entry, cccDNA, capsid formation, viral morphogenesis and virion secretion, as well as therapeutic vaccines.

P- Reviewer: A, Rodriguez-Frias F S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Miller RH, Kaneko S, Chung CT, Girones R, Purcell RH. Compact organization of the hepatitis B virus genome. Hepatology. 1989;9:322-327. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Seeger C, Mason WS. Hepatitis B virus biology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:51-68. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Summers J, Mason WS. Replication of the genome of a hepatitis B--like virus by reverse transcription of an RNA intermediate. Cell. 1982;29:403-415. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Das K, Xiong X, Yang H, Westland CE, Gibbs CS, Sarafianos SG, Arnold E. Molecular modeling and biochemical characterization reveal the mechanism of hepatitis B virus polymerase resistance to lamivudine (3TC) and emtricitabine (FTC). J Virol. 2001;75:4771-4779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bartholomeusz A, Tehan BG, Chalmers DK. Comparisons of the HBV and HIV polymerase, and antiviral resistance mutations. Antivir Ther. 2004;9:149-160. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Cane PA, Mutimer D, Ratcliffe D, Cook P, Beards G, Elias E, Pillay D. Analysis of hepatitis B virus quasispecies changes during emergence and reversion of lamivudine resistance in liver transplantation. Antivir Ther. 1999;4:7-14. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Günther S, Fischer L, Pult I, Sterneck M, Will H. Naturally occurring variants of hepatitis B virus. Adv Virus Res. 1999;52:25-137. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Chotiyaputta W, Lok AS. Hepatitis B virus variants. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:453-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Girones R, Miller RH. Mutation rate of the hepadnavirus genome. Virology. 1989;170:595-597. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Nowak MA, Bonhoeffer S, Hill AM, Boehme R, Thomas HC, McDade H. Viral dynamics in hepatitis B virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4398-4402. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Raimondo G, Allain JP, Brunetto MR, Buendia MA, Chen DS, Colombo M, Craxì A, Donato F, Ferrari C, Gaeta GB. Statements from the Taormina expert meeting on occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2008;49:652-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Torbenson M, Thomas DL. Occult hepatitis B. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:479-486. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Couroucé-Pauty AM, Plançon A, Soulier JP. Distribution of HBsAg subtypes in the world. Vox Sang. 1983;44:197-211. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Okamoto H, Tsuda F, Sakugawa H, Sastrosoewignjo RI, Imai M, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Typing hepatitis B virus by homology in nucleotide sequence: comparison of surface antigen subtypes. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:2575-2583. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Fang ZL, Zhuang H, Wang XY, Ge XM, Harrison TJ. Hepatitis B virus genotypes, phylogeny and occult infection in a region with a high incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3264-3268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cao GW. Clinical relevance and public health significance of hepatitis B virus genomic variations. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5761-5769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kurbanov F, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M. Geographical and genetic diversity of the human hepatitis B virus. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:14-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Norder H, Couroucé AM, Coursaget P, Echevarria JM, Lee SD, Mushahwar IK, Robertson BH, Locarnini S, Magnius LO. Genetic diversity of hepatitis B virus strains derived worldwide: genotypes, subgenotypes, and HBsAg subtypes. Intervirology. 2004;47:289-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 630] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Thedja MD, Muljono DH, Nurainy N, Sukowati CH, Verhoef J, Marzuki S. Ethnogeographical structure of hepatitis B virus genotype distribution in Indonesia and discovery of a new subgenotype, B9. Arch Virol. 2011;156:855-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Huy TT, Ushijima H, Quang VX, Win KM, Luengrojanakul P, Kikuchi K, Sata T, Abe K. Genotype C of hepatitis B virus can be classified into at least two subgroups. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:283-292. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Davies J, Littlejohn M, Locarnini SA, Whiting S, Hajkowicz K, Cowie BC, Bowden DS, Tong SY, Davis JS. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B in the Indigenous people of northern Australia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1234-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lusida MI, Nugrahaputra VE, Soetjipto R, Nagano-Fujii M, Sasayama M, Utsumi T, Hotta H. Novel subgenotypes of hepatitis B virus genotypes C and D in Papua, Indonesia. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2160-2166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mulyanto SN, Surayah K, Tjahyono AA, Jirintai S, Takahashi M, Okamoto H. Identification and characterization of novel hepatitis B virus subgenotype C10 in Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. Arch Virol. 2010;155:705-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mulyanto SN, Wahyono A, Jirintai S, Takahashi M, Okamoto H. Analysis of the full-length genomes of novel hepatitis B virus subgenotypes C11 and C12 in Papua, Indonesia. J Med Virol. 2011;83:54-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sakamoto T, Tanaka Y, Orito E, Co J, Clavio J, Sugauchi F, Ito K, Ozasa A, Quino A, Ueda R. Novel subtypes (subgenotypes) of hepatitis B virus genotypes B and C among chronic liver disease patients in the Philippines. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:1873-1882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Utsumi T, Nugrahaputra VE, Amin M, Hayashi Y, Hotta H, Lusida MI. Another novel subgenotype of hepatitis B virus genotype C from papuans of Highland origin. J Med Virol. 2011;83:225-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mulyanto P, Depamede SN, Wahyono A, Jirintai S, Nagashima S, Takahashi M, Nishizawa T, Okamoto H. Identification of four novel subgenotypes (C13-C16) and two inter-genotypic recombinants (C12/G and C13/B3) of hepatitis B virus in Papua province, Indonesia. Virus Res. 2012;163:129-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pourkarim MR, Amini-Bavil-Olyaee S, Kurbanov F, Van Ranst M, Tacke F. Molecular identification of hepatitis B virus genotypes/subgenotypes: revised classification hurdles and updated resolutions. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7152-7168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yang J, Xing K, Deng R, Wang J, Wang X. Identification of Hepatitis B virus putative intergenotype recombinants by using fragment typing. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:2203-2215. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Sugauchi F, Orito E, Ichida T, Kato H, Sakugawa H, Kakumu S, Ishida T, Chutaputti A, Lai CL, Ueda R. Hepatitis B virus of genotype B with or without recombination with genotype C over the precore region plus the core gene. J Virol. 2002;76:5985-5992. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Shi W, Carr MJ, Dunford L, Zhu C, Hall WW, Higgins DG. Identification of novel inter-genotypic recombinants of human hepatitis B viruses by large-scale phylogenetic analysis. Virology. 2012;427:51-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sánchez-Tapias JM, Costa J, Mas A, Bruguera M, Rodés J. Influence of hepatitis B virus genotype on the long-term outcome of chronic hepatitis B in western patients. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1848-1856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yuen MF, Wong DK, Sablon E, Tse E, Ng IO, Yuan HJ, Siu CW, Sander TJ, Bourne EJ, Hall JG. HBsAg seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B in the Chinese: virological, histological, and clinical aspects. Hepatology. 2004;39:1694-1701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Thakur V, Guptan RC, Kazim SN, Malhotra V, Sarin SK. Profile, spectrum and significance of HBV genotypes in chronic liver disease patients in the Indian subcontinent. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:165-170. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Livingston SE, Simonetti JP, McMahon BJ, Bulkow LR, Hurlburt KJ, Homan CE, Snowball MM, Cagle HH, Williams JL, Chulanov VP. Hepatitis B virus genotypes in Alaska Native people with hepatocellular carcinoma: preponderance of genotype F. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:5-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Livingston SE, Simonetti JP, Bulkow LR, Homan CE, Snowball MM, Cagle HH, Negus SE, McMahon BJ. Clearance of hepatitis B e antigen in patients with chronic hepatitis B and genotypes A, B, C, D, and F. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1452-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Chen CH, Eng HL, Lee CM, Kuo FY, Lu SN, Huang CM, Tung HD, Chen CL, Changchien CS. Correlations between hepatitis B virus genotype and cirrhotic or non-cirrhotic hepatoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:552-555. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Genotypes and clinical phenotypes of hepatitis B virus in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1207-1209. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and spontaneous hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion in Taiwanese hepatitis B carriers. J Med Virol. 2004;72:363-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Chan HL, Hui AY, Wong ML, Tse AM, Hung LC, Wong VW, Sung JJ. Genotype C hepatitis B virus infection is associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2004;53:1494-1498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Chu CM, Liaw YF. Genotype C hepatitis B virus infection is associated with a higher risk of reactivation of hepatitis B and progression to cirrhosis than genotype B: a longitudinal study of hepatitis B e antigen-positive patients with normal aminotransferase levels at baseline. J Hepatol. 2005;43:411-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Watanabe K, Takahashi T, Takahashi S, Okoshi S, Ichida T, Aoyagi Y. Comparative study of genotype B and C hepatitis B virus-induced chronic hepatitis in relation to the basic core promoter and precore mutations. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:441-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Yuen MF, Sablon E, Yuan HJ, Wong DK, Hui CK, Wong BC, Chan AO, Lai CL. Significance of hepatitis B genotype in acute exacerbation, HBeAg seroconversion, cirrhosis-related complications, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2003;37:562-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Sumi H, Yokosuka O, Seki N, Arai M, Imazeki F, Kurihara T, Kanda T, Fukai K, Kato M, Saisho H. Influence of hepatitis B virus genotypes on the progression of chronic type B liver disease. Hepatology. 2003;37:19-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Chan HL, Tse CH, Mo F, Koh J, Wong VW, Wong GL, Lam Chan S, Yeo W, Sung JJ, Mok TS. High viral load and hepatitis B virus subgenotype ce are associated with increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:177-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 46. | Wai CT, Fontana RJ, Polson J, Hussain M, Shakil AO, Han SH, Davern TJ, Lee WM, Lok AS. Clinical outcome and virological characteristics of hepatitis B-related acute liver failure in the United States. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:192-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kato H, Orito E, Gish RG, Bzowej N, Newsom M, Sugauchi F, Suzuki S, Ueda R, Miyakawa Y, Mizokami M. Hepatitis B e antigen in sera from individuals infected with hepatitis B virus of genotype G. Hepatology. 2002;35:922-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Chudy M, Schmidt M, Czudai V, Scheiblauer H, Nick S, Mosebach M, Hourfar MK, Seifried E, Roth WK, Grünelt E. Hepatitis B virus genotype G monoinfection and its transmission by blood components. Hepatology. 2006;44:99-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Norder H, Couroucé AM, Magnius LO. Complete genomes, phylogenetic relatedness, and structural proteins of six strains of the hepatitis B virus, four of which represent two new genotypes. Virology. 1994;198:489-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 556] [Cited by in RCA: 587] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Bartholomeusz A, Schaefer S. Hepatitis B virus genotypes: comparison of genotyping methods. Rev Med Virol. 2004;14:3-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Schaefer S. Hepatitis B virus taxonomy and hepatitis B virus genotypes. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:14-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Zhang ZH, Zhang L, Lu MJ, Yang DL, Li X. Establishment of reference sequences of hepatitis B virus genotype B and C in China. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2009;17:891-895. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Zhang Z, Xia J, Sun B, Dai Y, Li X, Schlaak JF, Lu M. In vitro and in vivo replication of a chemically synthesized consensus genome of hepatitis B virus genotype B. J Virol Methods. 2015;213:57-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Yuan Q, Ou SH, Chen CR, Ge SX, Pei B, Chen QR, Yan Q, Lin YC, Ni HY, Huang CH. Molecular characteristics of occult hepatitis B virus from blood donors in southeast China. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:357-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Hsu CW, Yeh CT. Emergence of hepatitis B virus S gene mutants in patients experiencing hepatitis B surface antigen seroconversion after peginterferon therapy. Hepatology. 2011;54:101-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Carman WF, Zanetti AR, Karayiannis P, Waters J, Manzillo G, Tanzi E, Zuckerman AJ, Thomas HC. Vaccine-induced escape mutant of hepatitis B virus. Lancet. 1990;336:325-329. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Carman WF, Korula J, Wallace L, MacPhee R, Mimms L, Decker R. Fulminant reactivation of hepatitis B due to envelope protein mutant that escaped detection by monoclonal HBsAg ELISA. Lancet. 1995;345:1406-1407. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Theamboonlers A, Chongsrisawat V, Jantaradsamee P, Poovorawan Y. Variants within the “a” determinant of HBs gene in children and adolescents with and without hepatitis B vaccination as part of Thailand’s Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI). Tohoku J Exp Med. 2001;193:197-205. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Colson P, Borentain P, Motte A, Henry M, Moal V, Botta-Fridlund D, Tamalet C, Gérolami R. Clinical and virological significance of the co-existence of HBsAg and anti-HBs antibodies in hepatitis B chronic carriers. Virology. 2007;367:30-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Lada O, Benhamou Y, Poynard T, Thibault V. Coexistence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBs Ag) and anti-HBs antibodies in chronic hepatitis B virus carriers: influence of “a” determinant variants. J Virol. 2006;80:2968-2975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Kazim SN, Sarin SK, Sharma BC, Khan LA, Hasnain SE. Characterization of naturally occurring and Lamivudine-induced surface gene mutants of hepatitis B virus in patients with chronic hepatitis B in India. Intervirology. 2006;49:152-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Koyanagi T, Nakamuta M, Sakai H, Sugimoto R, Enjoji M, Koto K, Iwamoto H, Kumazawa T, Mukaide M, Nawata H. Analysis of HBs antigen negative variant of hepatitis B virus: unique substitutions, Glu129 to Asp and Gly145 to Ala in the surface antigen gene. Med Sci Monit. 2000;6:1165-1169. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Chiou HL, Lee TS, Kuo J, Mau YC, Ho MS. Altered antigenicity of ‘a’ determinant variants of hepatitis B virus. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:2639-2645. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Oon CJ, Lim GK, Ye Z, Goh KT, Tan KL, Yo SL, Hopes E, Harrison TJ, Zuckerman AJ. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B virus vaccine variants in Singapore. Vaccine. 1995;13:699-702. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Kaymakoglu S, Baran B, Onel D, Badur S, Atamer T, Akyuz F. Acute hepatitis B due to immune-escape mutations in a naturally immune patient. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2014;77:262-265. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Ma Q, Wang Y. Comprehensive analysis of the prevalence of hepatitis B virus escape mutations in the major hydrophilic region of surface antigen. J Med Virol. 2012;84:198-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Luongo M, Critelli R, Grottola A, Gitto S, Bernabucci V, Bevini M, Vecchi C, Montagnani G, Villa E. Acute hepatitis B caused by a vaccine-escape HBV strain in vaccinated subject: sequence analysis and therapeutic strategy. J Clin Virol. 2015;62:89-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Lu M, Lorentz T. De novo infection in a renal transplant recipient caused by novel mutants of hepatitis B virus despite the presence of protective anti-hepatitis B surface antibody. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1323-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Zheng X, Weinberger KM, Gehrke R, Isogawa M, Hilken G, Kemper T, Xu Y, Yang D, Jilg W, Roggendorf M. Mutant hepatitis B virus surface antigens (HBsAg) are immunogenic but may have a changed specificity. Virology. 2004;329:454-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Tian Y, Xu Y, Zhang Z, Meng Z, Qin L, Lu M, Yang D. The amino Acid residues at positions 120 to 123 are crucial for the antigenicity of hepatitis B surface antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2971-2978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Wu C, Deng W, Deng L, Cao L, Qin B, Li S, Wang Y, Pei R, Yang D, Lu M. Amino acid substitutions at positions 122 and 145 of hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) determine the antigenicity and immunogenicity of HBsAg and influence in vivo HBsAg clearance. J Virol. 2012;86:4658-4669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Ito K, Qin Y, Guarnieri M, Garcia T, Kwei K, Mizokami M, Zhang J, Li J, Wands JR, Tong S. Impairment of hepatitis B virus virion secretion by single-amino-acid substitutions in the small envelope protein and rescue by a novel glycosylation site. J Virol. 2010;84:12850-12861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Vigerust DJ, Shepherd VL. Virus glycosylation: role in virulence and immune interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:211-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 420] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Chen Y, Qian F, Yuan Q, Li X, Wu W, Guo X, Li L. Mutations in hepatitis B virus DNA from patients with coexisting HBsAg and anti-HBs. J Clin Virol. 2011;52:198-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Wu C, Zhang X, Tian Y, Song J, Yang D, Roggendorf M, Lu M, Chen X. Biological significance of amino acid substitutions in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for glycosylation, secretion, antigenicity and immunogenicity of HBsAg and hepatitis B virus replication. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:483-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Yu DM, Li XH, Mom V, Lu ZH, Liao XW, Han Y, Pichoud C, Gong QM, Zhang DH, Zhang Y. N-glycosylation mutations within hepatitis B virus surface major hydrophilic region contribute mostly to immune escape. J Hepatol. 2014;60:515-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Zhang ZH, Li L, Zhao XP, Glebe D, Bremer CM, Zhang ZM, Tian YJ, Wang BJ, Yang Y, Gerlich W. Elimination of hepatitis B virus surface antigen and appearance of neutralizing antibodies in chronically infected patients without viral clearance. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:424-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Zhang JM, Xu Y, Wang XY, Yin YK, Wu XH, Weng XH, Lu M. Coexistence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and heterologous subtype-specific antibodies to HBsAg among patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1161-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Hsu HY, Chang MH, Ni YH, Lin HH, Wang SM, Chen DS. Surface gene mutants of hepatitis B virus in infants who develop acute or chronic infections despite immunoprophylaxis. Hepatology. 1997;26:786-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Hu Q, Huang JG, Lei YC, Huang HP, Yang Y, Yang DL. Detection of mutants of the “a” determinant region of hepatitis B surface antigen S gene among Wuhan childhood patients. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2005;13:594-596. [PubMed] |

| 81. | Wang CM, Han GR, Wang GJ. The relationship between hepatitis B virus S gene variation,genetype and immunoprophylaxis failure to intrauterine infection of hepatitis B virus. Zhonghua Chuanranbing Zazhi. 2009;27:114-117. [DOI] [Full Text] |