Published online Dec 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i45.12865

Peer-review started: June 3, 2015

First decision: June 19, 2015

Revised: July 9, 2015

Accepted: August 31, 2015

Article in press: August 31, 2015

Published online: December 7, 2015

Processing time: 187 Days and 0.6 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the long-term outcomes of Oddi sphincter preserved cholangioplasty with hepatico-subcutaneous stoma (OSPCHS) and risk factors for recurrence in hepatolithiasis.

METHODS: From March 1993 to December 2012, 202 consecutive patients with hepatolithiasis underwent OSPCHS at our department. The Oddi sphincter preserved procedure consisted of common hepatic duct exploration, stone extraction, hilar bile duct plasty, establishment of subcutaneous stoma to the bile duct. Patients with recurrent stones can undergo stone extraction and/or biliary drainage via the subcutaneous stoma which can be incised under local anesthesia. The long-term results were reviewed. Cox regression model was employed to analyze the risk factors for stone recurrence.

RESULTS: Ninety-seven (48.0%) OSPCHS patients underwent hepatic resection concomitantly. The rate of surgical complications was 10.4%. There was no perioperative death. The immediate stone clearance rate was 72.8%. Postoperative cholangioscopic lithotomy raised the clearance rate to 97.0%. With a median follow-up period of 78.5 mo (range: 2-233 mo), 24.8% of patients had recurrent stones, 2.5% had late development of cholangiocarcinoma, and the mortality rate was 5.4%. Removal of recurrent stones and/or drainage of inflammatory bile via subcutaneous stoma were conducted in 44 (21.8%) patients. The clearance rate of recurrent stones was 84.0% after subsequent choledochoscopic lithotripsy via subcutaneous stoma. Cox regression analysis showed that residual stone was an independent prognostic factor for stone recurrence.

CONCLUSION: In selected patients with hepatolithiasis, OSPCHS achieves excellent long-term outcomes, and residual stone is an independent prognostic factor for stone recurrence.

Core tip: The treatment of hepatolithiasis remains a great challenge among various biliary operations. Residual and recurrent stones are the most troublesome problem after surgery. The present study introduces an optional technique (OSPCHS) for hepatolithiasis. This procedure keeps the Oddi sphincter intact and reduces the postoperative reflux cholangitis, and OSPCHS also stresses the clearance of hepatobiliary lesions. Moreover, OSPCHS provides the recurrent patients with the minimal invasive treatment to avoid major surgery. OSPCHS generates a satisfactory long-term outcome for hepatolithiasis.

- Citation: Lian YG, Zhang WT, Xu Z, Ling XF, Wang LX, Hou CS, Wang G, Cui L, Zhou XS. Oddi sphincter preserved cholangioplasty with hepatico-subcutaneous stoma for hepatolithiasis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(45): 12865-12872

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i45/12865.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i45.12865

Hepatolithiasis is a common disease in Southeast Asia and is particularly prevalent in China[1]. It is characterized by repeated attacks of acute bacterial cholangitis with subsequent formation of pigment stones and strictures in the biliary system. Hepatolithiasis, at present, is still difficult to treat because of the high rate of residual or recurrent stones[1-3].

The definitive management of primary hepatolithiasis is to use a multidisciplinary approach, aiming to remove all biliary stones, establish adequate drainage to the biliary system, resect nonfunctioning liver segments that harbor bacteria and serve as foci of infection[3-5]. There are various treatment modalities for hepatolithiasis, including hepatectomy, intrahepatic duct exploration via choledochotomy, percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic lithotripsy (PTCSL), and Oddi sphincter preserved cholangioplasty with hepatico-subcutaneous stoma (OSPCHS)[6-9]. However, postoperative residual and recurrent stones occur in 20% of patients treated with these therapies[10]. Biliary-enteric anastomosis, which mostly includes choledochoduodenostomy and hepaticojejunostomy, is one of the most common procedures used for hepatolithiasis. However, our previous reports supported that choledochoduodenostomy was not an ideal approach to reduce cholangitis in hepatolithiasis and was not the best choice in the management of hepatolithiasis due to the loss of the anti-reflux function of the sphincter of Oddi[8,11]. Herman et al[12] found that patients who underwent liver resection associated with hepaticojejunostomy had a significantly higher recurrence rate of symptoms than patients submitted to liver resection alone (41.2% vs 0%, respectively, P = 0.0006). In the management of hepatolithiasis, we emphasize both complete eradication of hepatobiliary lesions and keeping the Oddi sphincter intact. In 1993, OSPCHS for hepatolithiasis was developed at our hospital and quickly spread to other hospitals in China[8].

Until now, the long-term outcomes of OSPCHS and risk factors for recurrence in hepatolithiasis have not been reported. In the current study, we reviewed the cases with hepatolithiasis treated surgically at our center in the past 20 years retrospectively and evaluated the long-term outcomes of OSPCHS and risk factors for recurrence in hepatolithiasis.

From March 1993 to December 2012, 202 hepatolithiasis cases who underwent OSPCHS were analyzed retrospectively. The patients ranged in age from 18 to 83 years with a median age of 55.0 years. The male to female ratio was 75:127. Of the 202 patients, 136 (67.6%) had at least one attack of acute cholangitis, 62 (30.7%) had previous biliary surgery, and 154 (76.2%) had extrahepatic bile duct stones. The demographic data of these patients are shown in Table 1. Preoperative evaluations included ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and/or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC). The primary long-term outcome measure was stone recurrence. Secondary long-term outcome measures were the development of cholangiocarcinoma and mortality. Stone recurrence was defined as new bile duct stone formation after complete initial clearance.

| Patients (n = 202) | |

| Age | 55 (18-83) |

| Male:female | 75:127 |

| Presentation | |

| Acute cholangitis | 36 (67.3) |

| Jaundice | 8 (4.0) |

| Liver abscess | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 54 (26.7) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 4 (2.0) |

| Previous biliary operation | 62 |

| Cholecystectomy | 25 (12.4) |

| Cholecystectomy plus CBD exploration | 23 (11.4) |

| CBD exploration | 6 (3.0) |

| Hepatectomy | 8 (4.0) |

| Concomitant extrahepatic stones | 154 |

| GB stones | 14 (6.9) |

| CBD stones | 94 (46.5) |

| GB + CBD stones | 46 (22.8) |

| Stone location | |

| Left | 58 (28.7) |

| Right | 34 (16.8) |

| Both | 110 (54.4) |

| Intrahepatic stricture | 118 (58.4) |

| Liver atrophy | 52 (25.7) |

| Biliary cirrhosis | 27 (3.5) |

The indications for OSPCHS in patients with hepatolithiasis were as follows: (1) no evidence of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction; (2) no indication of common bile duct (CBD) resection; (3) hilar bile duct stenosis; (4) biliary strictures were not completely corrected with hepatectomy alone; and (5) bilateral or diffuse hepatolithiasis. The indications for simultaneous hepatectomy included: (1) hepatolithiasis associated with biliary stenosis; (2) atrophy or fibrosis of the affected liver segment(s) or lobe; (3) the presence of liver abscess; (4) Child-Pugh A liver function without biliary cirrhosis; and (5) the patient’s general condition was good and could tolerate the operation.

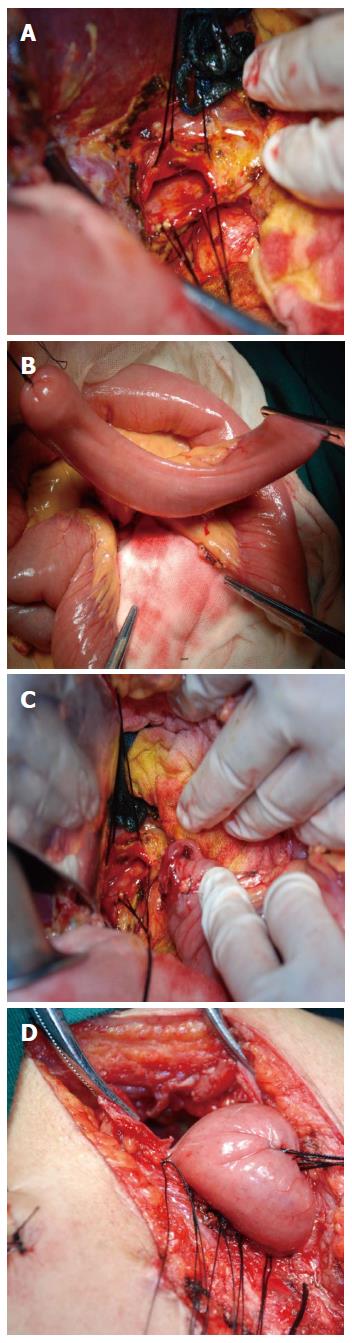

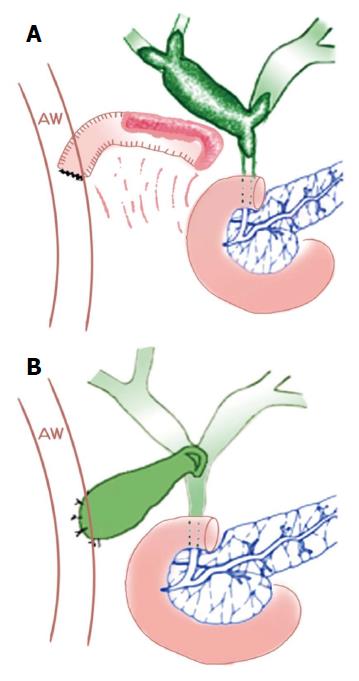

A right subcostal incision was made. Exploration of the CBD and hepatic duct was conducted through the incision. First, the primary or secondary bile duct stricture rings were incised. The choledochofiberscope was employed to remove the stone. Large and impacted stones were fragmented with plasma shock wave lithotripsy (PSWL)[13]. Subsequently, the opened bile ducts were stitched together to form a “hepatobiliary basin” (Figure 1A). Second, a segment of the jejunum 12-15 cm long with a vascular pedicle was intercepted 15-20 cm away from the Treitz ligament, and was stretched upward to the hilar via the colon, during which care was taken to avoid twisting the mesentery (Figure 1B). The proximal end of the free jejunum was closed. The jejunum segment was then flushed using 0.9% saline via the distal end. End-to-end anastomosis was performed between the proximal and distal ends of the jejunum. The third step consisted of reconstructing a subcutaneous stoma. Specifically, side-to-end anastomosis was performed between the distal end of the free jejunum segment and the “hepatobiliary basin” with an anastomotic diameter of approximately 3-5 cm (Figure 1C). The proximal end of the free jejunum segment was settled subcutaneously in the upper 1/3 segment of the incision, and was marked on the skin (Figure 1D). During the operations, all patients received cholangiography, CBD exploration, and T tube drainage. Drains were placed routinely in the Winslow foramen and/or the subphrenic space in all patients. There are two types of subcutaneous stoma: free jejunum as a subcutaneous stoma (Figure 2A) and gallbladder as a subcutaneous stoma (Figure 2B). The procedure using the gallbladder as a subcutaneous stoma has been previously described by our group[14]. If there were indications for liver resection, the stone-affected liver was also resected.

All patients had regular follow-up every 3 mo for the first year, and twice a year thereafter. The symptoms, physical examination, liver function tests and abdominal ultrasound, CT or MRCP were recorded. The median follow-up period was 78.5 mo (range: 2-233 mo).

Demographic and follow-up data of all patients were collected. Data were analyzed retrospectively. Overall survival was measured from the date of surgery to the time of death. Grouped data are expressed as median (range). Univariate analysis was conducted using χ2 test. Cumulative rates of stone recurrence were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier and log-rank test. The Cox regression model was used to analyze potential risk factors associated with stone recurrence. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using the SPSS version 22 (IBM, Armonk, New York, United States).

The operative procedures are listed in Table 2. Among the 202 patients, 105 underwent OSPCHS alone, and 97 underwent OSPCHS combined with hepatectomy. Left lateral sectionectomy was the major procedure for hepatolithiasis, followed by left hepatectomy.

| Type of operation | n (%) | |

| Subcutaneous stoma (n = 202) | Gallbladder as a subcutaneous stoma | 99 (49.0) |

| Free jejunum as a subcutaneous stoma | 103 (51.0) | |

| Hepatectomy (n = 97) | Left lateral sectionectomy | 65 (67.0) |

| Left hepatectomy | 19 (19.6) | |

| Segmentectomy of segment 6 | 5 (5.2) | |

| Segmentectomy of segment 5 | 1 (1.0) | |

| Left hepatectomy + right anterior segmentectomy | 1 (1.0) | |

| Segmentectomy of segment 3 | 1 (1.0) | |

| Segmentectomy of segment 5 + segment 6 | 1 (1.0) | |

| Segmentectomy of segment 6 + segment 7 | 3 (3.1) | |

| Segmentectomy of segment 7 + segment 8 | 1 (1.0) |

The short-term outcomes are shown in Table 3. The overall operative morbidity and hospital mortality rates were 10.4% and 0%, respectively. The most common complication was biliary leakage, followed by wound infection. Three patients (bile leakage = 1, hemobilia = 1, intra-abdominal bleeding = 1) received reoperations, and the remaining 18 cases underwent conservative management and recovered. The immediate stone clearance rate was 72.8%, and after additional choledochoscopic lithotripsy, the final stone clearance rate was 97.0%. Residual stones could not be completely removed in 6 patients, because of the uncorrected bile duct stenosis (n = 1) and stone location at peripheral bile ducts (n = 5) unreachable by cholangioscopy.

| Short-term outcome | Patients (n = 202) | Management |

| Complications | 21 (10.4) | |

| Biliary leakage | 9 (4.5) | Observation for 8 patients, and reoperation for 1 patient |

| Wound infection | 5 (2.5) | Dressing |

| Intra-abdominal bleeding | 2 (1.0) | Observation for 1 patient, and reoperation for 1 patient |

| Hemobilia | 2 (1.0) | Observation for 1 patient, and reoperation for 1 patient |

| Low limb thrombosis | 1 (0.5) | Observation |

| Pleural effusion | 1 (0.5) | Observation |

| Abdominal fungal infection | 1 (0.5) | Antibiotic |

| Perioperative mortality | 0 | |

| Immediate stone clearance | 147 (72.8) | |

| Final stone clearance | 196 (97.0) |

The long-term outcomes are shown in Table 4. With a median follow-up period of 78.5 mo, 50 (24.8%) patients developed recurrent stones. Among these, 28 (13.9%) appeared as acute cholangitis, which was cured using subcutaneous-stoma drainage plus antibiotics. Forty-four of fifty patients underwent stone extraction through subcutaneous stoma, while 2 patients refused. Recurrent stones were completely removed in 42 of 50 patients after 1 to 7 sessions of cholangioscopic lithotomy. After the complete eradication of recurrent stones, the subcutaneous stoma was then closed. The final clearance rate of recurrent stones was 84.0%.

| Long-term outcome | n (%) |

| Stone recurrence | 50 (24.8) |

| Recurrent attack of acute cholangitis | 28 (13.9) |

| Utilization of subcutaneous stoma | 42 (20.8) |

| Clearance of recurrent stones | 42 (84.0) |

| Development of cholangiocarcinoma | 5 (2.5) |

| Death | 11 (5.4) |

Eleven patients died during the follow-up, and 6 deaths were not related to the hepatolithiasis. Five (2.5% of the total) cases died of hepatolithiasis associated cholangiocarcinoma, 4 of whom developed stone recurrence and unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and the rest 1 patient underwent radical operation. The total mortality rate was 5.4% at the end of follow-up.

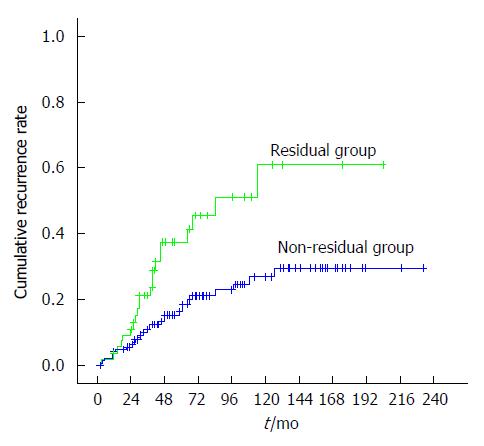

A total of nine factors were selected to identify the potential risk factors possibly associated with postoperative stone recurrence, including six patient factors [age (≥ 50 years vs < 50 years), gender (male vs female), biliary stenosis (yes vs no), previous biliary surgery (yes vs no), extrahepatic stones (yes vs no), and stone distribution (unilateral vs bilateral)], two operation factors [hepatectomy (yes vs no) and subcutaneous stoma type (gallbladder vs free jejunum)], and one postoperative factor [residual stones (yes vs no)]. All factors were analyzed with the Cox regression model, which indicated that only residual stone was an independent prognostic factor for stone recurrence (Table 5). The stone recurrence rate was significantly higher in patients with residual stones, and there was a significant difference in the cumulative stone recurrence rate between the two groups as revealed by the Kaplan-Meier log-rank test (P = 0.001) (Figure 3).

| Variable | Univariate analysis, P value | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | ||

| Age | 0.572 | |||

| Gender | 0.883 | |||

| Previous biliary surgery | 0.237 | |||

| Biliary stenosis | 0.689 | |||

| Extrahepatic stones | 0.417 | |||

| Stone distribution | 0.217 | |||

| Hepatectomy | 0.191 | |||

| Types of subcutaneous stoma | 0.414 | |||

| Residual stones | 0.008 | 2.587 | 1.396-4.795 | 0.003 |

Hepatolithiasis is usually complicated by recurrent cholangitis, pancreatitis and liver abscess, and it even leads to secondary biliary cirrhosis and cholangiocarcinoma[15]. In China, many investigators and surgeons have been exploring this issue for more than half a century. The famous basic principle of hepatolithiasis management, “clearance of stones, correction of strictures, removal of hepatobiliary lesions, and restoration of bile drainage”, has been widely acknowledged in China and around the world[2,16,17]. Following these principles, the definitive surgical approach for each patient should be designed individually according to the divergent hepatobiliary lesions.

Theoretically, partial hepatectomy is the most definitive treatment for hepatolithiasis because it removes all of the hepatic stones and strictured bile ducts within the resected liver segment(s), thus reducing the subsequent risk of recurrent stones and cholangiocarcinoma[3,7,18,19]. However, approximately 50% of intrahepatic lesions of stones and ductal strictures are distributed bilaterally, even diffusely. Under these complicated conditions, thorough resection of the affected liver is impossible. Uncorrected strictures inevitably result in recurrent cholangitis. We found that keeping the function of the sphincter of Oddi intact is useful to reduce cholangitis in patients with uncorrected strictures or remnant stones due to the anti-reflux function of the sphincter of Oddi[11]. Therefore, it is suggested that the sphincter of Oddi should be preserved if there is no laxity or restriction.

According to the review of the previous literature, the present study is so far the only one that evaluated the long-term results of OSPCHS and factors for recurrence in hepatolithiasis. The pivot of OSPCHS is to ensure that the sphincter of Oddi has normal function. However, it is difficult to make a definitive evaluation preoperatively, although ultrasonography, CT, ERCP, MRCP, PTC, and intraoperative finding can provide useful data. Tan et al[2] proposed that the functional status of the sphincter of Oddi was accurately assessed by choledochoscopic manometry via T-tube or by peroral endoscopic manometry postoperatively. We have established a relatively simple method for intraoperative judgement: if the intraoperative exploration shows that a 16-Fr catheter can pass through the orifice of the duodenum ampulla, the sphincter of Oddi can be considered to have normal function.

Residual and recurrent stones are the most troublesome problem after treatment for hepatolithiasis[7]. Therefore, absent residual or recurrent stones and cholangitis were regarded as an important way to evaluate the efficacy of all modalities for hepatolithiasis treatment. The incidence of residual stones has been markedly reduced from 62.3% to 19.8%[10,16]. In our study, the residual stone rate after OSPCHS for hepatolithiasis was 27.2% and was comparable with the two above-mentioned reports. This study indicated that residual stones was an independent risk factor for stone recurrence. According to our clinical practice, the intraoperative key in treating complicated hepatolithiasis is resection of the affected liver, correction of strictures and removal of impacted stones. It is suggested that the appropriate time frame for the operation is within 6 h, and additional postoperative choledochoscopic lithotripsy can significantly improve the stone clearance rate. In this study, the final stone clearance rate was much higher (97%) with the use of choledochoscopy and PSWL compared with the immediate stone clearance rate (72.8%).

Intraoperative ultrasonic scanning can detect stones as small as 2 mm with an accuracy rate of 98.7%[20]. Application of the intraoperative ultrasound-guided fiberoptic choledochoscope can significantly reduce the residual stone rate of intrahepatic biliary calculi (5.4% vs 19%, respectively, P = 0.025) and significantly improve the efficacy of hepatolithiasis[21]. With the rapid development of computer technology, digital medicine has become a new direction in surgery. Compared with traditional hepatectomy, hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis based on 3-dimensional reconstruction technique had a significantly lower stone residual rate (0% vs 9.5%) and stone recurrence rate (3.6% vs 23.8%)[16].

With the advent of endoscopic and image-directed percutaneous approaches, it is increasingly uncommon to require a surgical approach for recurrent stones[22,23]. Various noninvasive procedures, such as PTCSL and peroral cholangioscopy, have been reported[24,25]. Although PTCSL has been widely applied in Western countries with the advantage of avoiding operation, there still exist complications, including low stone clearance, hemobilia, and percutaneous tract dilation, which may incur pain to the patients[2,26]. Similarly, peroral cholangioscopic lithotomy also attains a lower stone clearance rate (64%) as reported in the previous report[27]. For the convenience in the eradication of recurrent stones, Beckingham et al[28] designed a subparietal hepaticojejunal access loop and indicated that the access loop permits long-term access to the intrahepatic ducts, allowing removal of stones with minimal patient discomfort and low morbidity. However, this approach permanently undermines the physiological anti-reflux function of the sphincter of Oddi, possibly increasing the recurrence rate of stones.

In 1993, we developed a new operative procedure in which hepaticoplasty was performed using a free segment of the jejunum or gallbladder for a subcutaneous stoma and preservation of the sphincter of Oddi[14]. Its aim was to set up a tunnel between the biliary duct and tela subcutanea to remove recurrent stones and drain the bile in recurrent cholangitis in a minimally invasive way. In our study, patients with recurrent stones underwent stone clearance and biliary drainage via the subcutaneous stoma which can be incised under local anesthesia whenever the patients present with symptoms suggestive of cholangitis. The follow-up data showed that subcutaneous stoma offers the advantage of permanent percutaneous access to intrahepatic ducts and is readily available for reusage subsequently without the need for further surgery if stones recur at a later stage.

Hepatolithiasis is a well-known risk factor for the occurrence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma[1,29]. The occurrence rate of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in patients with hepatolithiasis ranges from 2% to 12%[30]. In our study, 2.5% of patients developed cholangiocarcinoma during follow-up. The development of cholangiocarcinoma is the main factor compromising the long-term survival in patients with hepatolithiasis[1,16]. Unfortunately, regardless of advances in diagnosis modalities, diagnosing cholangiocarcinoma in patients with hepatolithiasis remains challenging, and the diagnostic rate has been reported to span from 0% to 37.5%[16]. Hence, a suspicion of malignancy is necessary when managing patients with hepatolithiasis, and careful follow-up for cholangiocarcinoma is needed.

However, this study has its limitations. As it is not a prospective and randomized controlled trial and was conducted in a single center, it may somewhat produce some bias. Clinically, it is very difficult to design a control group in which the patients’ Oddi sphincter will be damaged iatrogenically. In the near future we will carry out a survey in multiple centers to further investigate the advantages and disadvantages of OSPCHS.

In summary, this study shows that OSPCHS can be a safe and effective treatment option for well-selected patients with hepatolithiasis, and it achieves excellent long-term outcomes. A combination of different treatment modalities is conducive to decreasing the residual stone rate and improving the results of patients with hepatolithiasis.

Hepatolithiasis is a prevalent disease in China, and surgical treatment is needed because of the serious complications such as acute cholangitis and biliary cirrhosis. However, the long-term outcomes of Oddi sphincter preserved cholangioplasty with hepatico-subcutaneous stoma (OSPCHS) and risk factors for recurrence in hepatolithiaisis remain unclear.

Many reports have showed that partial hepatectomy is the most definitive treatment for hepatolithiasis. However, the high incidence of residual and recurrent stones is still a major challenge. The high incidence of reflux cholangitis caused by traditional hepaticojejunostomy is the major complication during follow-up. In this study, the authors tried to introduce an optional approach for effective and minimally invasive therapy of recurrent stones.

The authors created an optional technique (OSPCHS) for hepatolithiasis. The hepatobiliary lesions could be resected, with simultaneous construction of a subcutaneous stoma. The subcutaneous stoma allowed to remove recurrent stones or drain the inflammatory bile and avoid major reoperation. The high incidence of reflux cholangitis caused by hepaticojejunostomy could be avoided by preserving the sphincter of Oddi.

Lian YG et al performed OSPCHS for treatment of hepatolithiasis. OSPCHS achieves good long-term outcomes, and residual stone is an independent prognostic factor for stone recurrence. This study may present a strategy for treatment of complicated hepatolithiasis and patients with a high risk of recurrent stones.

OSPCHS in well-selected patients is safe and effective for treatment of hepatolithiasis.

This manuscript addresses the outcome of OSPCHS for hepaticolithiasis. This paper is interesting.

P- Reviewer: Shrestha A S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Li SQ, Liang LJ, Peng BG, Hua YP, Lv MD, Fu SJ, Chen D. Outcomes of liver resection for intrahepatic stones: a comparative study of unilateral versus bilateral disease. Ann Surg. 2012;255:946-953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tan J, Tan Y, Chen F, Zhu Y, Leng J, Dong J. Endoscopic or laparoscopic approach for hepatolithiasis in the era of endoscopy in China. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:154-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yang T, Lau WY, Lai EC, Yang LQ, Zhang J, Yang GS, Lu JH, Wu MC. Hepatectomy for bilateral primary hepatolithiasis: a cohort study. Ann Surg. 2010;251:84-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vetrone G, Ercolani G, Grazi GL, Ramacciato G, Ravaioli M, Cescon M, Varotti G, Del Gaudio M, Quintini C, Pinna AD. Surgical therapy for hepatolithiasis: a Western experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:306-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lai EC, Ngai TC, Yang GP, Li MK. Laparoscopic approach of surgical treatment for primary hepatolithiasis: a cohort study. Am J Surg. 2010;199:716-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yoon YS, Han HS, Shin SH, Cho JY, Min SK, Lee HK. Laparoscopic treatment for intrahepatic duct stones in the era of laparoscopy: laparoscopic intrahepatic duct exploration and laparoscopic hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 2009;249:286-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cheon YK, Cho YD, Moon JH, Lee JS, Shim CS. Evaluation of long-term results and recurrent factors after operative and nonoperative treatment for hepatolithiasis. Surgery. 2009;146:843-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 8. | Ling XF, Xu Z, Wang LX, Hou CS, Xiu DR, Zhang TL, Zhou XS. Long-term outcomes of choledochoduodenostomy for hepatolithiasis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123:137-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nuzzo G, Clemente G, Giovannini I, De Rose AM, Vellone M, Sarno G, Marchi D, Giuliante F. Liver resection for primary intrahepatic stones: a single-center experience. Arch Surg. 2008;143:570-573; discussion 574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Uchiyama K, Kawai M, Ueno M, Ozawa S, Tani M, Yamaue H. Reducing residual and recurrent stones by hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:626-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ling X, Xu Z, Wang L, Hou C, Xiu D, Zhang T, Zhou X. Is Oddi sphincterotomy an indication for hepatolithiasis? Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2268-2272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Herman P, Perini MV, Pugliese V, Pereira JC, Machado MA, Saad WA, D’Albuquerque LA, Cecconello I. Does bilioenteric anastomosis impair results of liver resection in primary intrahepatic lithiasis? World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3423-3426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xu Z, Wang L, Zhang N, Deng S, Xu Y, Zhou X. Clinical applications of plasma shock wave lithotripsy in treating postoperative remnant stones impacted in the extra- and intrahepatic bile ducts. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:646-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cui L, Xu Z, Ling XF, Wang LX, Hou CS, Wang G, Zhou XS. Laparoscopic hepaticoplasty using gallbladder as a subcutaneous tunnel for hepatolithiasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3350-3355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cheung MT, Wai SH, Kwok PC. Percutaneous transhepatic choledochoscopic removal of intrahepatic stones. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1409-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fang CH, Liu J, Fan YF, Yang J, Xiang N, Zeng N. Outcomes of hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis based on 3-dimensional reconstruction technique. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:280-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dong J, Lau WY, Lu W, Zhang W, Wang J, Ji W. Caudate lobe-sparing subtotal hepatectomy for primary hepatolithiasis. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1423-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cho JY, Han HS, Yoon YS, Shin SH. Outcomes of laparoscopic liver resection for lesions located in the right side of the liver. Arch Surg. 2009;144:25-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee TY, Chen YL, Chang HC, Chan CP, Kuo SJ. Outcomes of hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. World J Surg. 2007;31:479-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Li F, Cheng J, He S, Li N, Zhang M, Dong J, Jiang L, Cheng N, Xiong X. The practical value of applying chemical biliary duct embolization to chemical hepatectomy for treatment of hepatolithiasis. J Surg Res. 2005;127:131-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pan W, Xu E, Fang H, Deng M, Xu R. Surgical treatment of complicated hepatolithiasis using the ultrasound-guided fiberoptic choledochoscope. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:497-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Matsushima K, Soybel DI. Operative management of recurrent choledocholithiasis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:2312-2317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tsuyuguchi T, Miyakawa K, Sugiyama H, Sakai Y, Nishikawa T, Sakamoto D, Nakamura M, Yasui S, Mikata R, Yokosuka O. Ten-year long-term results after non-surgical management of hepatolithiasis, including cases with choledochoenterostomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:795-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Uenishi T, Hamba H, Takemura S, Oba K, Ogawa M, Yamamoto T, Tanaka S, Kubo S. Outcomes of hepatic resection for hepatolithiasis. Am J Surg. 2009;198:199-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee SE, Jang JY, Lee JM, Kim SW. Selection of appropriate liver resection in left hepatolithiasis based on anatomic and clinical study. World J Surg. 2008;32:413-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chen C, Huang M, Yang J, Yang C, Yeh Y, Wu H, Chou D, Yueh S, Nien C. Reappraisal of percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic lithotomy for primary hepatolithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:505-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Okugawa T, Tsuyuguchi T, K C S, Ando T, Ishihara T, Yamaguchi T, Yugi H, Saisho H. Peroral cholangioscopic treatment of hepatolithiasis: Long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:366-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Beckingham IJ, Krige JE, Beningfield SJ, Bornman PC, Terblanche J. Subparietal hepaticojejunal access loop for the long-term management of intrahepatic stones. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1360-1363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kim HJ, Kim JS, Suh SJ, Lee BJ, Park JJ, Lee HS, Kim CD, Bak YT. Cholangiocarcinoma Risk as Long-term Outcome After Hepatic Resection in the Hepatolithiasis Patients. World J Surg. 2015;39:1537-1542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tabrizian P, Jibara G, Shrager B, Schwartz ME, Roayaie S. Hepatic resection for primary hepatolithiasis: a single-center Western experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:622-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |