Published online Nov 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i43.12430

Peer-review started: March 31, 2015

First decision: May 18, 2015

Revised: June 2, 2015

Accepted: July 8, 2015

Article in press: July 8, 2015

Published online: November 21, 2015

Processing time: 232 Days and 5.9 Hours

AIM: To determine risk factors associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment failure after direct acting antivirals in patients with complex treatment histories.

METHODS: All HCV mono-infected patients who received treatment at our institution were queried. Analysis was restricted to patients who previously failed treatment with boceprevir (BOC) or telaprevir (TVR) and started simeprevir (SMV) and sofosbuvir (SOF) ± ribavirin (RBV) between December 2013 and June 2014. Patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/HCV co-infection or patients who received a liver transplant in the past were excluded. Viral loads were recorded while on treatment and after treatment. Data collection continued until December, 31st 2014 when data analysis was initiated. Patients missing virologic outcomes data were not included in the analysis. Analysis of 35 patients who had virologic outcome data available resulted in eight patients who were viral load negative at the end of treatment with SMF/SOF but later relapsed. Data related to patient demographics, HCV infection, and treatment history was collected in order to identify risk factors shared among patients who failed treatment with SMF/SOF.

RESULTS: Eight patients who were treated with the first generation HCV protease inhibitors BOC or TVR in combination with pegylated-interferon (PEG) and RBV who failed this triple therapy were subsequently re-treated with an off-label all-oral regimen of SMV and SOF for 12 wk, with RBV in seven cases. Treatment was initiated before the Food and Drug Administration approved a 24-wk SMV/SOF regimen for patients with liver cirrhosis. All eight patients had an end of treatment response, but later relapsed. Eight (100%) patients were male. Mean age was 56 (range, 49-64). Eight (100%) patients had previously failed PEG/RBV dual therapy at least once in addition to prior failure with triple therapy. Total number of times treated ranged from 3-6 (mean 3.8). Eight (100%) patients were male had liver cirrhosis as determined by Fibroscan or MRI. Seven (87.5%) patients had genotype 1a HCV. Seven (87.5%) patients had over 1 million IU/mL HCV RNA at the time of re-treatment.

CONCLUSION: This study identifies factors associated with SMV/SOF treatment failure and provides evidence that twleve weeks of SMV/SOF/RBV is insufficient in cirrhotics with high-titer genotype 1a HCV.

Core tip: Direct acting antivirals are revolutionizing the treatment of chronic hepatitis C (HCV) infection, but are also increasing the number of patients who have failed multiple rounds of treatment. Information about these patients is needed to plan salvage treatment strategies. We present eight patients who failed treatment with the first generation protease inhibitors and subsequently failed treatment with simeprevir and sofosbuvir. Their shared characteristics include a history of failed treatment with interferon/ribavirin and liver cirrhosis. Seven had genotype 1a HCV and a high viral load. Our findings suggest that patients with cirrhosis and high viral load remain hard-to-treat.

- Citation: Hartman J, Bichoupan K, Patel N, Chekuri S, Harty A, Dieterich D, Perumalswami P, Branch AD. Re-re-treatment of hepatitis C virus: Eight patients who relapsed twice after direct-acting-antiviral drugs. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(43): 12430-12438

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i43/12430.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i43.12430

Over 170 million people worldwide have chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection[1,2]. HCV is a leading cause of liver-related mortality and is now responsible for more deaths than human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in the United States[3,4]. The goal of treatment is to achieve a sustained virologic response (SVR), defined as undetectable HCV viral load 12 or 24 wk after the end of treatment[5]. Patients who achieve an SVR have decreased morbidity and mortality compared to null responders[6]. For many years, the standard of care (SOC) for chronic HCV infection was dual therapy with pegylated-interferon (PEG) and ribavirin (RBV)[7], but much less toxic and more effective regimens are available now[8]. Information about the performance of new agents in various subgroups of patients is needed to optimize care.

Direct acting antiviral (DAA) drugs for HCV target specific viral proteins. The first DAAs to receive Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, boceprevir (BOC) and telaprevir (TVR), inhibit the HCV serine protease, NS3/4A[7]. BOC and TVR have several shortcomings, however, including their need to be combined with PEG and RBV, a relatively low barrier to resistance, toxicity, and poor activity against non-genotype 1 HCV[9]. Newer DAAs include sofosbuvir (SOF), a NS5B polymerase inhibitor, and simeprevir (SMV), a second phase NS3/4A protease inhibitor (PI)[10-12]. These medications were approved in the United States in late 2013 and were recommended as first-line agents in the January 2014 AASLD/IDSA practice guidelines[13]. Early studies of therapeutic regimens containing these agents reported SVR12 rates ranging from 93%-100%[12,14-17]. The success of these antivirals was very encouraging[18]; however, the efficacy of the newer DAAs has not been extensively studied in patients with advanced liver disease and complex treatment histories, including those previously exposed to BOC and/or TVR.

We examined a cohort of 47 HCV mono-infected patients who previously failed TVR or BOC and started SMV/SOF ± RBV between December 2013 and June 2014. All patients had genotype 1 HCV. All patients received at least one dose of any HCV medication. Patients with HIV/HCV co-infection or patients who received a liver transplant in the past were excluded. Viral loads were recorded for each patient while on-treatment and after treatment. Data collection continued until December, 31st 2014 when data analysis was initiated. The analysis was restricted to 35 patients who had virologic outcomes data available. Patients missing virologic outcomes data were not included in the analysis.

Eight patients (described in detail below) who were viral load negative at the end of treatment (EOT) with SMV/SOF later relapsed. The present study was conducted with approval of the Mount Sinai IRB in compliance with the Helsinki accord. Following the case presentations, the use of DAAs in patients with complex histories is reviewed, and suggestions for optimizing HCV treatment in the future are presented.

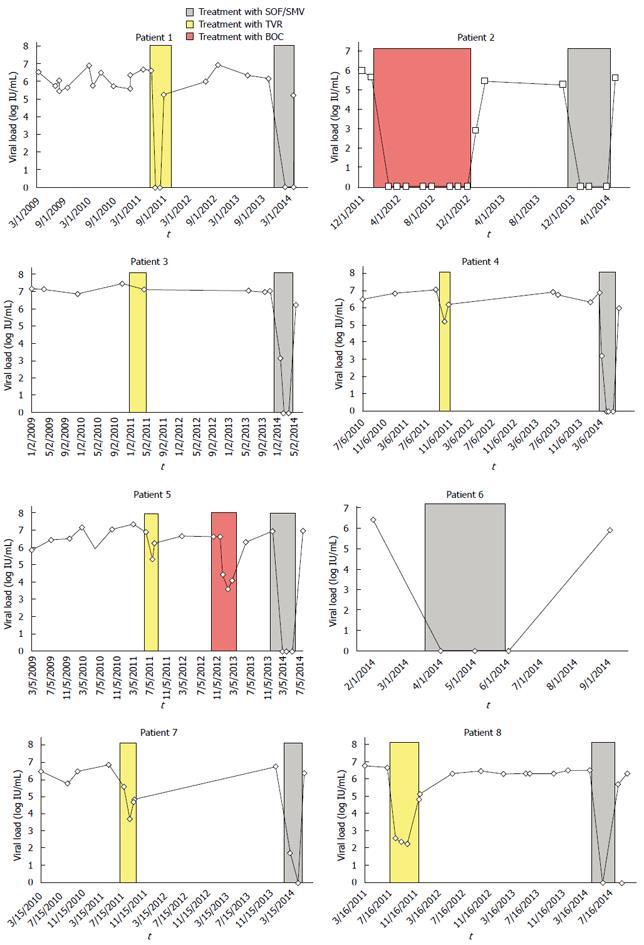

Case 1 is a 60-year-old white male with no significant medical history prior to being diagnosed with HCV genotype 1a in 1978. His risk factor for acquisition of HCV was intravenous drug use in the 1970s. He was previously a non-responder to PEG/RBV during two rounds of treatment. He was treated with PEG/RBV for a third time in 2009 after undergoing chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, and rituximab for treatment of non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphoma. Prior to starting treatment, his viral load was 3300000 IU/mL. At week 4, he had a 1-log drop in viral load (to 567910 IU/mL); however, by week 9, his viral load had increased and remained elevated so treatment was stopped. In 2011, a FibroScan has a score of 22 kPa, consistent with cirrhosis and he was treated with TVR/PEG/RBV. He had a rapid virological response (RVR) with undetectable viral load at week 4 (Figure 1A) that remained undetectable for the remainder of eight weeks of TVR-based triple therapy, however, the viral load was 169000 IU/mL at week 18 of PEG/RBV (five weeks after he completed TVR). Treatment was again stopped. A repeat FibroScan in 2013 suggested worsening cirrhosis (26 kPa) but he remained well compensated. In December, 2013, he began treatment with an off-label all-oral regimen of SMV/SOF/RBV. After 4 wk of treatment, his viral load went from 1449160 IU/mL to undetectable and remained undetected throughout the 12 wk of treatment. Four weeks post-EOT the viral load was 166684 IU/mL, indicating relapse.

Case 2 is a 49-year-old white male with no significant medical history prior to being diagnosed with HCV genotype 1b in 1993 at the age of 28. His risk factor for acquisition of HCV was a blood transfusion during surgery in his late teens for a sports-related injury. He was first treated in 2011 with TVR/PEG/RBV; however, he stopped TVR after two weeks due to a severe, diffuse rash. He continued PEG/RBV for a total of 12 wk but never had an undetectable HCV viral load. In 2012, his FibroScan was consistent with cirrhosis (33.3 kPa) but he had no evidence of decompensated liver disease. He was started on BOC after a 4-wk lead in with PEG/RBV. The viral load prior to initiation of treatment was 410332 IU/mL (Figure 1B). At week 8 (BOC week 4), he reported a small rash over the legs and arms, dysgeusia, and flu-like symptoms. His continued treatment and his viral load became undetectable at week 16 and remained so through week 48. Four weeks post-EOT, he relapsed with a viral load of 766 IU/mL. In January 2014, he was started on SOF/SMV/RBV, with a viral load of 180020 IU/mL. During the first two weeks of therapy, his viral load was below 43 IU/mL and after 6 wk the viral load was undetectable. Despite his viral load remaining undetectable for the remainder of therapy, he had a viral load of 370430 IU/mL at 4 wk post-EOT, indicating relapse.

Case 3 is a 54-year-old white male with no significant medical history prior to being diagnosed with HCV genotype 1a in 2006. His risk factor for acquisition of HCV was a tattoo that he received over 30 years prior to diagnosis. A liver biopsy in 2006 demonstrated cirrhosis. He was treated with PEG/RBV in 2006 at an outside institution but had difficulty tolerating this regimen due to side effects so treatment was stopped. He was re-treated with PEG/RBV in 2008 for 20 wk and was a partial responder. In 2011, he began treatment with TVR/PEG/RBV and remained on this regimen for 12 wk, although his viral load remained detectable (Figure 1C). In 2013, routine surveillance imaging revealed a 2.0 cm mass consistent with hepatocellular carcinoma. He received transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and then CT-guided thermal ablation of the lesion. Follow-up imaging showed complete ablation of the tumor and no recurrence. A FibroScan later that year was consistent with cirrhosis (32.8 kPa). He required diuretics for minimal ascites but was otherwise well compensated. He was started on treatment with SOF/SMV/RBV in 2014, with a viral load of 10349963 IU/mL. Two weeks after starting therapy, his viral load was 1363 IU/mL. The viral load dropped to less than 43 IU at week 6 and was undetectable for the remainder of therapy; however 6 wk post-EOT, his viral load was 1588696 IU/mL, indicating relapse.

Case 4 is a 50-year-old African American male with a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, major depression, substance abuse requiring inpatient rehabilitation, and HCV genotype 1a. His risk factor for acquisition was being incarcerated multiple times in the 1980s. He was treated once with PEG/RBV at an outside center without achieving an SVR. In 2009, he was re-treated with PEG/RBV. The course was complicated by severe, symptomatic anemia for which he was treated with Epoetin alpha; however, HCV treatment was stopped at 46 wk as he was again a non-responder. Later, an abdominal MRI revealed cirrhosis and portal hypertension. In 2011, he began PEG/RBV/TVR, with a viral load of 11361480 IU/mL. Treatment was complicated by symptomatic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hemorrhoidal bleeding. He was again prescribed Epoetin. At 4 wk of treatment, the viral load dropped to 152172 IU/mL, a 2-log decrease. Given this response, treatment was continued; however, at week 8, the viral load was 1557865 IU/mL so treatment was stopped early (Figure 1D). In 2014, he was started on SOF/SMV/RBV with a viral load of 7753010 IU/mL. After 4 wk, the viral load dropped to 1629 IU/mL and then became undetectable after 8 wk and remained so throughout the 12 wk of treatment. Four weeks post-EOT, his viral load was 808797 IU/mL, indicating relapse.

Case 5 is a 63-year-old white male with congenital absence of one kidney, hypertension, and HCV genotype 1a diagnosed in 2007. His risk factor for acquisition of HCV was intravenous drug use decades prior to diagnosis. He was first treated with PEG/RBV at another institution soon after diagnosis but was a non-responder. In 2011, after a FibroScan was consistent with cirrhosis (17 kPa), he was treated with PEG/RBV/TVR. Eight weeks after starting, the medication regimen was discontinued due to acute kidney injury attributed to dehydration requiring hospitalization for intravenous fluid hydration (Figure 1E). Months later, a FibroScan was consistent with worsening cirrhosis (34.3 kPa), although he remained well compensated. He was treated in November 2012 with PEG/RBV/BOC but was a non-responder. He began treatment with SOF/SMV/RBV in 2014, with a viral load of 8450674 IU/mL. After 4 wk, the viral load was undetectable and remained so throughout treatment. At 12 wk post-EOT, his viral load was 9485523 IU/mL, indicating late relapse.

Case 6 is a 53-year-old white male with no significant past medical history prior to being diagnosed with HCV genotype 1a in 2005. His risk factor for acquisition of HCV was a blood transfusion after a motor vehicle accident in Puerto Rico during his childhood. He had previously been treated with PEG/RBV at an outside center, which was discontinued early due to a severe episode of depression. He underwent treatment with PEG/RBV/TVR in 2012 but treatment was stopped after eight months due to virologic breakthrough. While awaiting new therapies, he underwent an MRI of the abdomen in 2013 that demonstrated changes consistent with cirrhosis and mild portal hypertension but no ascites or hepatocellular carcinoma. In February 2014, his viral load was 2429839 IU/mL (Figure 1F). He subsequently began treatment with a 12 wk course of SOF/SMV. Labs at week 4 and week 8 of treatment revealed an undetectable viral load. He remained viral load negative after completing treatment, however he had a viral load of 744508 IU/mL 12 wk post-EOT with SOF/SMV, indicating relapse.

Case 7 is a 64-year-old white male with no significant medical history prior to being diagnosed with HCV genotype 1a (unknown risk factor). He was first treated in 2010 with PEG/RBV but treatment was stopped after six-months as he was a non-responder. After an abdominal MRI in 2011 revealed cirrhosis and portal hypertension, he underwent treatment with TVR/PEG/RBV. Prior to initiation of therapy, his viral load was 3732211 IU/mL. At treatment week 2, his viral load was 4614 IU/mL, which increased to 45205 IU/mL at week 4 (Figure 1G). Triple therapy was discontinued after six weeks of treatment. In 2014, he was started on a 12 wk course of SOF/SMV/RBV. His viral load decreased from 5448450 IU/mL to 49 IU/mL at week 4 of treatment. His viral load subsequently became undetectable and remained undetectable through 12 wk of treatment. At four weeks post-EOT, his viral load was 2166059 IU/mL, indicating relapse.

Case 8 is a 54-year-old African-American male with a history of hypertension and HCV genotype 1a (risk factor unknown). He had previously failed four courses of PEG/RBV at an outside institution. In 2011, a FibroScan indicated cirrhosis (23.1 kPa). After FDA approval of PIs, he was started on treatment with TVR/PEG/RBV. Viral load prior to starting was 4512245 IU/mL. He initially had a decrease in viral load to 359 IU/mL at week 4 and 224 IU/mL at week 8 (Figure 1H). Treatment course was complicated by anemia treated with Epoetin alpha. He completed 12 wk of TVR but had a viral load of 63858 IU/mL at week 20, so treatment was discontinued. He was monitored throughout 2013 with a FibroScan showing worsening cirrhosis (26.3 kPa). In 2014, he was started on a 12 wk course of SOF/SMV/RBV with a viral load of 3108263 IU/mL. His viral load became undetectable at week 5 and remained so throughout the remainder of treatment. At week 4 post-EOT, he had a viral load of 491287 IU/mL, indicating relapse (Table 1).

| Case | Race | Age | Genotype | Test to diagnose cirrhosis | IL-28b | Total number of times treated (including DAAs) | Number of times treated with PEG/RBV dual therapy | Prior PI treatment | Time interval between PI and SMV/SOF (mo) | Viral load prior to SMV/SOF treatment (IU/mL) | RBV used with SM/SOF | Duration of treatment (wk) |

| 1 | White | 60 | 1a | Fibroscan (24 kPa) | CT | 5 | 3 | TVR | 30 | 1449160 | Yes | 12 |

| 2 | White | 49 | 1b | Fibroscan (33.3 kPa) | Unknown | 3 | 0 | TVR, BOC | 19 | 180020 | Yes | 12 |

| 3 | White | 54 | 1a | Fibroscan (32.8 kPa) | Unknown | 4 | 2 | TVR | 26 | 10349963 | Yes | 12 |

| 4 | African American | 50 | 1a | MRI | TT | 4 | 2 | TVR | 25 | 7753010 | Yes | 12 |

| 5 | White | 63 | 1a | Fibroscan (34.3 kPa) | Unknown | 4 | 1 | TVR, BOC | 12 | 8450674 | Yes | 12 |

| 6 | White | 53 | 1a | MRI | Unknown | 3 | 1 | TVR | -- | 2429839 | No | 12 |

| 7 | White | 64 | 1a | MRI | Unknown | 3 | 1 | TVR | 28 | 5448450 | Yes | 12 |

| 8 | African American | 54 | 1a | Fibroscan (26.3 kPa) | Unknown | 6 | 4 | TVR | 31 | 3108263 | Yes | 12 |

As DAA drug treatments for HCV gain widespread use, the number of patients who have failed multiple rounds of treatment will inevitably increase. This study provides data about eight patients who relapsed after 12 wk of treatment with SOF/SMV (RBV). Information about their shared characteristics helps to identify patients at high risk of failure, raises questions about what pre-treatment testing might be done in the future to optimize outcomes for patients with complex treatment histories, and highlights the need for future research to determine optimal salvage strategies. The cases have several features in common. All were male and all had cirrhosis. All had previously failed both dual therapy (PEG/RBV) and PI-based (TVR or BOC) triple therapy. Seven had genotype 1a HCV and seven had an HCV viral load over 1 million IU/mL at the time of re-re-treatment. Several of these shared features may have contributed to the most recent treatment failure.

Liver cirrhosis has been associated with treatment failure for many years. With PEG/RBV dual therapy, SVR rates were lower in patients with compensated cirrhosis than in those without cirrhosis, particularly among patients with genotype 1 HCV in whom SVR rates were about 20% lower in cirrhotics[18-20]. Patients with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis accounted for 9%-48% of patients enrolled in the larger trials of PIs[14,21-24]. The REALIZE trial, which had the highest proportion of patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis (48%), found SVR rates were inversely related to the stage of fibrosis, with 75% in mild fibrosis, 67% in advanced fibrosis, and 47% in cirrhosis after treatment with PEG/RBV. Additionally, relapse rates were higher in previous partial or null responders with cirrhosis than without (10% vs 4%)[15,23].

The mechanism for reduced SVR rates with more advanced liver disease has not been well elucidated. It is possible that cirrhosis prevents even perfusion of the liver with antiviral drugs, creating pockets that have low drug concentrations where HCV can persist. Alternatively, patients with cirrhosis have impaired immunity, as indicated by their enhanced susceptibility to infection[24]. Studies suggest that prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) may have an immunosuppressive effect by inhibiting the production of proinflammatory cytokines by macrophages. PGE2 has been found in higher concentrations in cirrhotics and additionally has higher bioavailability in cirrhotics due to decreased levels of albumin, which normally binds to PGE2 and therefore decreases its bioavailability[25]. Whatever its cause, the immunodeficiency of patients with liver cirrhosis may contribute to treatment failure by slowing the kinetics of the second phase of viral decline-either by reducing the killing of infected cells or by reducing the process that allows infected cells to clear the virus.

Recent studies of all-oral regimens have reported favorable results even in patients with liver cirrhosis. In COSMOS, of 41 treatment-naive and null responders to PEG/RBV with METAVIR fibrosis stage F3-F4 treated with SMV/SOF ± RBV for 12 wk, only three patients failed[12]. The LONESTAR trial contained a cohort of 40 patients who failed PI-based triple therapy with BOC or TVR, over half of the patients had compensated cirrhosis. On SOF and ledipasvir, an NS5A inhibitor, the SVR12 rate was 95% without RBV and 100% with RBV[16]. The ELECTRON trial used the same regimen of SOF/ledipasvir and in the cohort with cirrhotics and prior null responders, the SVR12 rate was 70% without RBV and 100% with RBV[17]. Many of the case patients in our study had advanced cirrhosis. When considering how the promising published results relate to our investigation of patients who failed treatment, it is important to keep in mind that not all patients with cirrhosis have the same degree of liver damage. Rather, there is a spectrum of disease among cirrhotics. Many of the case patients had advanced cirrhosis, and this may have increased their susceptibility to treatment failure. FibroScan scores, because they report liver stiffness as a continuous variable, may help stratify the extent of liver scarring and delineate high-risk patients.

The treatment regimen chosen for our patients was based on results of the COSMOS study at a time when the FDA had not yet approved SMV/SOF combination therapy. COSMOS reported SVR rates in patients with METAVIR F3-F4 fibrosis who were treated with SMV/SOF for 12 wk of 93% compared to 93% in patients treated with SMV/SOF/RBV and 100% in patients treated with SMV/SOF for 24 wk[12]. In November 2014, the FDA approved a 24 wk regimen of SMV/SOF for patients with cirrhosis. All of the case patients in our case series were treated before this approval with 12 wk of treatment. This longer regimen reflects the growing awareness of the persistent challenge of treating patients with liver cirrhosis despite the availability of DAAs. The treatment failure of our patients highlights a potential limitation with early adoption of HCV treatment regimens that are not yet approved by the FDA.

High viral load is a second factor predisposing to treatment failure. An early study on PEG/RBV by Fried et al[26] showed that SVR rates were significantly lower in patients with viral load over 800000 IU/mL than in patients with lower viral load: 41% vs 56%, respectively. Multivariate logistic regression analysis has shown that low baseline viral load is an independent predictor of SVR to treatment with PEG/RBV[27]. Showing a similar trend, early studies of SMV had SVR rates of 91% in patients with low viral load vs 77% in patients with high viral load[28]. COSMOS did not look at the difference in SVR based on pre-treatment viral load in patients treated with SMV/SOF. Seven of the cases had a viral load over 1 million IU/mL prior to treatment, which likely further increased susceptibility to treatment failure.

In addition to these factors, baseline polymorphisms and mutations that develop during exposure to antiviral drugs may contribute to the failure of DAA-based treatments. Numerous viral sequence variants confer partial or complete resistance to SMV. The barrier to resistance is especially low for genotype 1a HCV. Q80K is one of the most common resistance mutations in the HCV NS3/4A protease. It is often present at baseline. The importance of the Q80K mutation was exhibited in the QUEST-1 study where treatment naïve patients were treated with SMV/PEG/RBV. The SVR rate was 71% in patients with genotype 1a and 90% in patients with genotype 1b, but it was 85% in genotype 1a patients without the baseline Q80K mutation and 52% in genotype 1a patients with the mutation[28]. Tests for the Q80K mutation are available, but were not used prior to treating the patients in our case series as there is no formal recommendation to use this test in clinical practice and insurance companies were not providing consistent coverage for this test. There are additional baseline polymorphisms that exist in genotype 1a HCV that make it challenging to treat[29]. In addition, prior exposure to TVR/BOC can promote the development of cross-resistant mutations, such as R155[30]. Therefore, patients such as those presented here who previously were treated with PIs could have baseline and/or acquired cross-resistant mutations to SMV. Baseline polymorphisms that reduce effectiveness of SOF have also been described. Using deep-sequencing methods, Donaldson et al[31] identified numerous low-frequency substitutions in the target of SOF, the NS5B (nonstructural protein 5B) polymerase. Two, L159F and V321A, were located in the catalytic pocket of the viral enzyme and likely altered drug binding. Research is needed to determine the utility of HCV RNA sequence analysis in selecting optimal first-line and salvage strategies.

The strengths of this report include its timeliness, real-world setting, and case series with eight patients. The real-world setting of this study allows us to report experiences of these new medications in clinical practice. Given the number of cases reported here, we are able to highlight common factors for relapse to better identify and understand patients who may be at higher risk for failure. Data reported in registration trials is not always complete and generalizable to clinical practice. In our cohort, physicians selected the HCV treatment regimen based on their best clinical judgment, which can include early adoption of promising regimens based on data available. Limitations of this report include a lack of resistance data on our case series. Resistance analysis is not yet commonly used in clinical practice but consideration should be given to incorporate into recommendations for patients who fail DAA regimens in order to identify optimal salvage regimens. Barriers to coverage of resistance analysis including Q80K mutation analysis may have a better chance to be overcome once adopted into guidelines.

Early studies examining the efficacy of IFN-free regimens had very high SVR rates in patients with and without liver cirrhosis. The treatment failure in our eight patients was disappointing for the patients and their providers and carries a significant economic burden, as well. The pharmaceutical cost of a 12 wk regimen of SMV/SOF is $150360. Research is needed to identify the underlying causes of DAA-based treatment failure and to identify the best salvage regimens for patients who have failed on specific drug combinations.

The goal of treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is to achieve a sustained virologic response. Historically, the standard of care for chronic HCV infection was dual therapy with pegylated-interferon and ribavirin but less toxic and more effective regimens are available now.

Direct acting antiviral (DAA) drugs for HCV target specific viral proteins. The first DAAs to receive Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval were boceprevir and telaprevir, inhibitors of the HCV serine protease NS3/4A. Newer DAAs include sofosbuvir, a NS5B polymerase inhibitor, and simeprevir, a second phase NS3/4A protease inhibitor. These drugs are do not require the addition of interferon and have less toxicity and therefore are now recommended as first-line agents by the FDA for HCV genotype 1. Early studies of therapeutic regimens containing these agents reported sustained virologic response (SVR) 12 rates ranging from 93%-100%.

DAA drugs are increasing the number of patients who achieve SVR, but are also increasing the number of patients who have failed multiple rounds of treatment. The efficacy of the newer DAAs has not been extensively studied in patients with advanced liver disease and complex treatment histories, including those previously exposed to BOC and/or TVR. Information about patients who repeatedly fail DAA-based therapy may help guide the development of salvage strategies.

This study identifies a number of factors associated with SMV/SOF treatment failure, which included prior treatment with earlier DAAs, HCV 1a genotype, liver cirrhosis, and high pre-treatment viral load.

Hepatitis C is an infectious disease caused by the HCV, a small infectious agent, which primarily infects cells of the liver. Cirrhosis is advanced scarring of the liver, often induced by chronic viral infection, including Hepatitis C, or chronic alcohol abuse, which render the liver unable to conduct a number of necessary functions. Sustained virologic response describes when there are no viral particles detected in the blood 12 or 24 wk after the end of treatment. Direct-acting antiviral drugs are medications that target specific parts of the HCV in order to prevent the virus from duplicating.

This is a comprehensive observational study in which the authors characterized and analyzed patients who failed treatment with new DAAs to uncover risk factors associated with SMV/SOF for treatment of chronic HCV infection. Identifying factors associated with treatment failure prior to initiating treatment is important in order to optimize treatment strategies and reduce health care costs. The results suggest that patients with complex histories may benefit from individualized risk analysis prior to treatment.

P- Reviewer: Slomiany BL S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | World Health Organization. Global alert and response (GAR). Hepatitis C. 2012; Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/hepatitis/whocdscsrlyo2003/en/index4.html. |

| 2. | Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:558-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1927] [Cited by in RCA: 1931] [Article Influence: 96.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lavanchy D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2009;29 Suppl 1:74-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 933] [Cited by in RCA: 939] [Article Influence: 58.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Deuffic-Burban S, Poynard T, Sulkowski MS, Wong JB. Estimating the future health burden of chronic hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus infections in the United States. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:107-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335-1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2320] [Cited by in RCA: 2240] [Article Influence: 140.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Morgan TR, Ghany MG, Kim HY, Snow KK, Shiffman ML, De Santo JL, Lee WM, Di Bisceglie AM, Bonkovsky HL, Dienstag JL, Morishima C, Lindsay KL, Lok AS; HALT-C Trial Group. Outcome of sustained virological responders with histologically advanced chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2010;52:833-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ghany MG, Nelson DR, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. An update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2011;54:1433-1444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 803] [Cited by in RCA: 844] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liang TJ, Ghany MG. Current and future therapies for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1907-1917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pawlotsky JM. The results of Phase III clinical trials with telaprevir and boceprevir presented at the Liver Meeting 2010: a new standard of care for hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection, but with issues still pending. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:746-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gao M, Nettles RE, Belema M, Snyder LB, Nguyen VN, Fridell RA, Serrano-Wu MH, Langley DR, Sun JH, O’Boyle DR. Chemical genetics strategy identifies an HCV NS5A inhibitor with a potent clinical effect. Nature. 2010;465:96-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 773] [Cited by in RCA: 762] [Article Influence: 50.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sofia MJ, Bao D, Chang W, Du J, Nagarathnam D, Rachakonda S, Reddy PG, Ross BS, Wang P, Zhang HR. Discovery of a β-d-2’-deoxy-2’-α-fluoro-2’-β-C-methyluridine nucleotide prodrug (PSI-7977) for the treatment of hepatitis C virus. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7202-7218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 467] [Cited by in RCA: 494] [Article Influence: 32.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jacobson IM, Ghalib RM, Rodriguez-Torres M, Younossi ZM, Corregidor A, Sulkowski MS, DeJesus E, Pearlman B, Rabinovitz M, Gitlin N, Lim JK, Pockros PJ, Fevery B, Lambrecht T, Ouwerkerk-Mahadevan S, Callewaert K, Symonds WT, Picchio G, Lindsay K, Beumont-Mauviel M, Lawitz E. SVR results of a once-daily regimen of simeprevir (TMC435) plus sofosbuvir (GS-7977) with or without ribavirin in cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic HCV genotype 1 treatment-naive and prior null responder patients: the COSMOS study. 64th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Washington DC: Abstract LB-3 2013; . |

| 13. | AASLD/IDSA/IAS-USA. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. Accessed April 24. 2014; Available from: http://hcvguidelines.org. |

| 14. | Sherman KE, Flamm SL, Afdhal NH, Nelson DR, Sulkowski MS, Everson GT, Fried MW, Adler M, Reesink HW, Martin M. Response-guided telaprevir combination treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1014-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 592] [Cited by in RCA: 602] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pol S, Roberts SK, Andreone P, Younossi Z, Diago M, Lawitz EJ, Focaccia R, Foster GR, Horban A, Lonjon-Domanec I, DeMasi R, van Heeswijk R, De Meyer S, Picchio G, Witek J, Zeuzem S. Efficacy and safety of telaprevir-based regimens in cirrhotic patients with HCV genotype 1 and prior peginterferon/riba- virin treatment failure: subanalysis of the REALIZE phase III study. Hepatology. 2011;54:374A-375A. Abstract 31. |

| 16. | Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, Hyland RH, Ding X, Mo H, Symonds WT, McHutchison JG, Membreno FE. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:515-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 429] [Cited by in RCA: 443] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gane EJ, Stedman CA, Hyland RH, Pang PS, Ding X, Symonds WT, McHutchison JG. ELECTRON: all-oral sofosbuvir-based 12-week regimens for the treatment of chronic HCV GT 1 infection. 48th annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver; April 24-28. Amsterdam: The Netherlands 2013; . |

| 18. | Vezali E, Aghemo A, Colombo M. A review of the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in cirrhosis. Clin Ther. 2010;32:2117-2138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bruno S, Shiffman ML, Roberts SK, Gane EJ, Messinger D, Hadziyannis SJ, Marcellin P. Efficacy and safety of peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus ribavirin in hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:388-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abergel A, Hezode C, Leroy V, Barange K, Bronowicki JP, Tran A, Alric L, Castera L, Bernard PH, Henquell C. Peginterferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin for treatment of chronic hepatitis C with severe fibrosis: a multicentre randomized controlled trial comparing two doses of peginterferon alpha-2b. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:811-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Poordad F, McCone J, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, Jacobson IM, Reddy KR, Goodman ZD, Boparai N. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1996] [Cited by in RCA: 1980] [Article Influence: 141.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, Di Bisceglie AM, Reddy KR, Bzowej NH, Marcellin P, Muir AJ, Ferenci P, Flisiak R. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1905] [Cited by in RCA: 1861] [Article Influence: 132.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, Lawitz E, Diago M, Roberts S, Focaccia R, Younossi Z, Foster GR, Horban A. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2417-2428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1230] [Cited by in RCA: 1214] [Article Influence: 86.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fierer J, Finley F. Deficient serum bactericidal activity against Escherichia coli in patients with cirrhosis of the liver. J Clin Invest. 1979;63:912-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | O’Brien AJ, Fullerton JN, Massey KA, Auld G, Sewell G, James S, Newson J, Karra E, Winstanley A, Alazawi W. Immunosuppression in acutely decompensated cirrhosis is mediated by prostaglandin E2. Nat Med. 2014;20:518-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4847] [Cited by in RCA: 4747] [Article Influence: 206.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Berg T, Sarrazin C, Herrmann E, Hinrichsen H, Gerlach T, Zachoval R, Wiedenmann B, Hopf U, Zeuzem S. Prediction of treatment outcome in patients with chronic hepatitis C: significance of baseline parameters and viral dynamics during therapy. Hepatology. 2003;37:600-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jacobson IM, Dore GJ, Foster GR, Fried MW, Radu M, Rafalsky VV, Moroz L, Craxi A, Peeters M, Lenz O. Simeprevir with pegylated interferon alfa 2a plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-1): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384:403-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 355] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Berger KL, Triki I, Cartier M, Marquis M, Massariol MJ, Böcher WO, Datsenko Y, Steinmann G, Scherer J, Stern JO. Baseline hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3 polymorphisms and their impact on treatment response in clinical studies of the HCV NS3 protease inhibitor faldaprevir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:698-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shang L, Lin K, Yin Z. Resistance mutations against HCV protease inhibitors and antiviral drug design. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:694-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Donaldson EF, Harrington PR, O’Rear JJ, Naeger LK. Clinical evidence and bioinformatics characterization of potential hepatitis C virus resistance pathways for sofosbuvir. Hepatology. 2015;61:56-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |