Published online Sep 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i34.9999

Peer-review started: March 1, 2015

First decision: April 13, 2015

Revised: April 23, 2015

Accepted: July 15, 2015

Article in press: July 15, 2015

Published online: September 14, 2015

Processing time: 198 Days and 19.7 Hours

AIM: To explore a reasonable method of digestive tract reconstruction, namely, antrum-preserving double-tract reconstruction (ADTR), for patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction (AEG) and to assess its efficacy and safety in terms of long-term survival, complications, morbidity and mortality.

METHODS: A total of 55 cases were retrospectively collected, including 18 cases undergoing ADTR and 37 cases of Roux-en-Y reconstruction (RY) for AEG (Siewert types II and III) at North Sichuan Medical College. The cases were divided into two groups. The clinicopathological characteristics, perioperative outcomes, postoperative complications, morbidity and overall survival (OS) were compared for the two different reconstruction methods.

RESULTS: Basic characteristics including sex, age, body mass index (BMI), Siewert type, pT status, pN stage, and lymph node metastasis were similar in the two groups. No significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of perioperative outcomes (including the length of postoperative hospital stay, operating time, and intraoperative blood loss) and postoperative complications (consisting of anastomosis-related complications, wound infection, respiratory infection, pleural effusion, lymphorrhagia, and cholelithiasis). For the ADTR group, perioperative recovery indexes such as time to first flatus (P = 0.002) and time to resuming a liquid diet (P = 0.001) were faster than those for the RY group. Moreover, the incidence of reflux esophagitis was significantly decreased compared with the RY group (P = 0.048). The postoperative morbidity and mortality rates for overall postoperative complications and the rates of tumor recurrence and metastasis were not significantly different between the two groups. Survival curves plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log-rank test demonstrated similar outcomes for the ADTR and RY groups. Multivariate analysis of significantly different factors that presented as covariates on Cox regression analysis to assess the survival and recurrence among AEG patients showed that age, gender, BMI, pleural effusion, time to resuming a liquid diet, lymphorrhagia and tumor-node-metastasis stage were important prognostic factors for OS of AEG patients, whereas the selection of surgical method between ADTR and RY was shown to be a similar prognostic factor for OS of AEG patients.

CONCLUSION: ADTR by jejunal interposition presents similar rates of tumor recurrence, metastasis and long-term survival compared with classical reconstruction with RY esophagojejunostomy; however, it offers considerably improved near-term quality of life, especially in terms of early recovery and decreased reflux esophagitis. Thus, ADTR is recommended as a worthwhile digestive tract reconstruction method for Siewert types II and III AEG.

Core tip: Antrum-preserving double-tract reconstruction (ADTR) was introduced to improve the near-term quality of life and decrease reflux esophagitis in patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. The clinicopathological characteristics, perioperative outcomes, postoperative complications, morbidity and overall survival after ADTR and Roux-en-Y reconstruction (RY) (ADTR group, n = 18 vs RY group, n = 37) were retrospectively compared to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the procedures. The results of the study demonstrated that ADTR was technically safe and feasible, offering an agreeable near-term quality of life, especially in terms of early recovery and the alleviation of reflux esophagitis. ADTR may be a worthwhile digestive tract reconstruction method for Siewert types II and III adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction.

-

Citation: Xiao JW, Liu ZL, Ye PC, Luo YJ, Fu ZM, Zou Q, Wei SJ. Clinical comparison of antrum-preserving double tract reconstruction

vs roux-en-Y reconstruction after gastrectomy for Siewert types II and III adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(34): 9999-10007 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i34/9999.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i34.9999

The incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction (AEG), a type of cancer involving the anatomical border of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ), has dramatically increased over the past several decades in Western countries. Although accurate measurement of its distribution is difficult, epidemiological data from Asian countries have not shown a similar trend; however, AEG is a fairly common malignancy in Japan, Asia, South America, and Eastern Europe[1-6].

AEGs in the transitional junction between stratified squamous epithelium and simple columnar epithelium have distinct pathological and clinical characteristics compared with esophageal cancer and gastric cancer[7]. Some investigators have reported on differences in gender predilection, prognosis and potential etiology after separating carcinomas of the EGJ and distal esophagus or stomach based on their anatomical relationship to the EGJ. These reports revealed that the anatomic location of these increasingly prevalent tumors could be associated with specific characteristics that are predictive of clinical outcome. Controversy and confusion persist regarding the location, definition and classification of AEGs as well as regarding the causes of these tumors[8-10].

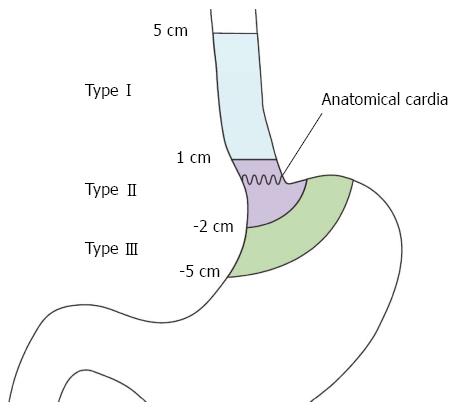

Among the limited consensus about the classification of AEG and the definition of the cardia, the criteria established by Siewert et al[11] are now widely accepted and used. According to Siewert’s criteria, AEG is defined as a tumor with an epicenter within 5 cm proximal or distal to the endoscopic cardia where the longitudinal gastric folds end. The Siewert classification divides AEGs into three subtypes, allowing the resection approaches to be codified and comparisons to be made between surgical series (Figure 1)[2,11,12]. Type I tumors are adenocarcinomas of the distal esophagus, which usually arise from areas with specialized intestinal metaplasia of the esophagus. Type II tumors are true carcinomas of the cardia arising immediately at the EGJ, whereas Type III tumors are subcardial gastric carcinomas infiltrating the EGJ and distal esophagus from below. In recent decades, numerous studies have demonstrated that the location of the AEG affects therapeutic management and influences the prognosis and long-term quality of life.

Despite endoscopic screening and advances in multimodality therapy, the prognosis of these tumors is poor, with a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of approximately 20%. Surgical resection with lymphadenectomy continues to play a pivotal role in the treatment of AEG. Although total gastrectomy is recommended as the standard treatment, 60% to 70% of tumors localizing in the cardiac region can obtain a radical cure by proximal gastrectomy with appropriate lymphadenectomy. This approach is widely applied, especially in cases of early gastric cancer[13,14]. Radical tumor resection and long-term tumor-free survival are ideal treatment outcomes, and patients’ quality of life can be restored to normal if functional alimentary canal reconstruction is performed soon after diagnosis.

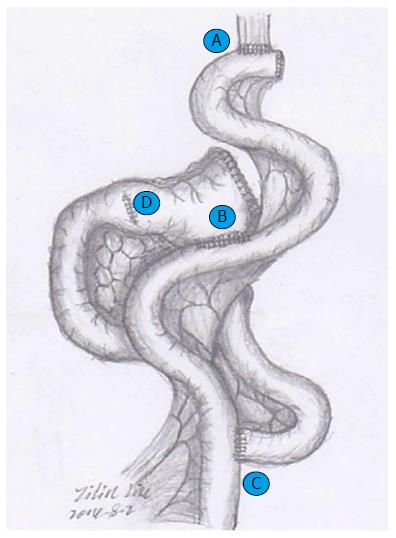

Although Siewert’s classification is used to determine treatment strategy, the approach remains controversial. An optimal surgical strategy has not yet been established. Therefore, we have developed a modified double-track anastomosis for alimentary canal reconstruction after radical proximal gastrectomy by combining the advantages of Roux-en-Y and functional reconstruction of the stomach with jejunal interposition, which preserves the antrum so that chyme can be thoroughly mixed prior to transit to the duodenal passage and reduces the morbidity of backflow sequelae by offering an adequate evacuation tract (Figure 2). The purpose of this study was to compare the surgical outcomes for two reconstruction methods, antrum-preserving double-tract reconstruction (ADTR) and traditional Roux-en-Y reconstruction (RY) with esophagojejunostomy, after total gastrectomy, and to determine the best surgical approach for optimal postoperative quality of life.

We retrospectively collected a database of 55 consecutive patients (48 males and 7 females) with AEG who underwent curative surgical resection between January 2012 and June 2013 at the Department of General Surgery of the Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College, China. The type of AEG was classified according to Siewert’s criteria. All of the patients suffering from synchronous gastric double cancer who had a history of or concurrent other cancer(s), distant metastasis, a previous history of surgery for gastric or esophageal cancer or gastric stump cancer were excluded. Furthermore, no patient underwent preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

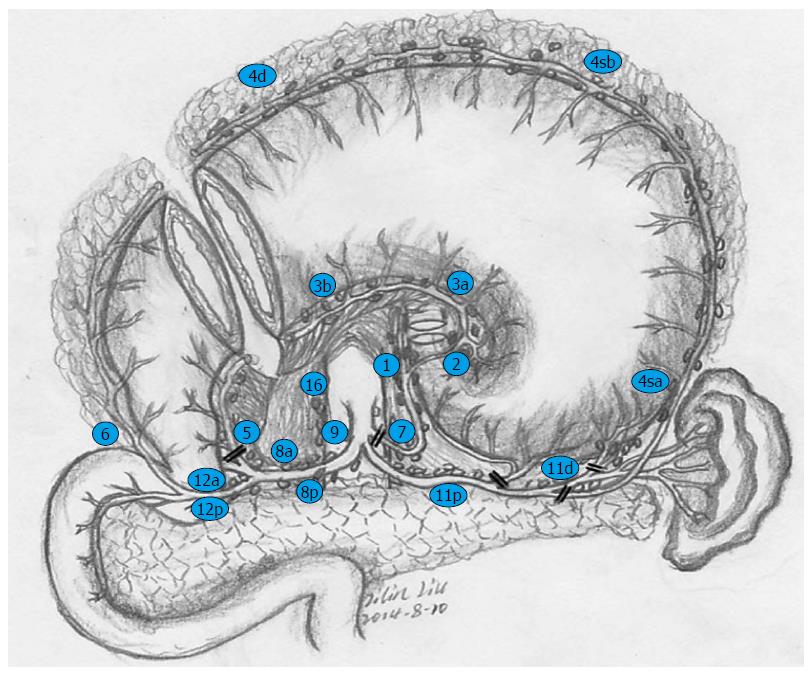

Before surgery, hematological examination, abdominal ultrasonography, chest radiography, or computed tomography (CT) scan were routinely performed on all patients for tumor staging. The Siewert type of the tumors was determined preoperatively by upper gastrointestinal fiberscopic screening and biopsy, which also offered references for the surgical approach. To summarize these findings, the preoperative Siewert’s subtype and surgical procedure were ultimately determined. In accordance with the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3)[15], D2 lymph node dissection was performed in patients on the basis of tumor location, size and lymph node metastasis. Appropriate combined organ resection (i.e., splenectomy) was performed to achieve a curative resection.

All of the patients were operated on via an abdominal approach, and procedures including laparotomy and laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy were implemented via a midline upper abdominal incision. For the RY group, standard D2 lymphadenectomy and total gastrectomy were performed. The jejunum was divided approximately 20 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz; then, the distal jejunal limb was brought through the transverse mesocolon via the retrocolic route, and the stump was closed with a linear stapler. An end-to-side esophagojejunostomy was performed mechanically with a circular stapler, while the bottom of the proximal jejunum limb was anastomosed to the side of the Roux limb with a circular stapler at approximately 35 cm distal to the esophagojejunal anastomosis. For the ADTR group, the surgical procedure and its lymphadenectomy details are shown in Figures 2 and 3. At least 6 cm distal to the lower edge of the tumor, the remnant gastric antrum was retained and closed with a linear stapler after proximal gastrectomy. The jejunum was mobilized and severed approximately 15 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz. End-to-side esophagojejunostomy was implemented with a circular stapler between the stump closing of the distal jejunal limb and the esophagus, and a side-to-end jejunoduodenostomy was constructed with a circular stapler 35 cm distal to the esophagojejunal anastomosis. Finally, the remnant gastric antrum was anastomosed mechanically by a 6-8 cm side-to-side gastrojejunostomy with a linear stapler, approximately 20 cm proximal to the jejunoduodenal anastomosis.

Based on the American UICC 7th tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification[16,17], the gastric carcinoma scheme was used for Siewert types II and III AEG staging, and the regional lymph nodes and tumor histology were evaluated according to the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma 3rd English edition[18]. The survival data for all of the patients were ascertained in June 2014. During the follow-up period, which ranged from 12 to 30 mo (median 17 mo), all of the patients’ basic characteristics, including operative time, blood loss, postoperative time to first flatus, time to resuming a liquid diet, length of hospitalization, early and late postoperative complications and OS were collected and analyzed.

Quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± SD, whereas qualitative data are shown as prevalence. A two-sample Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to compare continuous data, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was performed to evaluate proportions. All-cause mortality and disease-specific survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. A multivariate analysis of significantly different factors was performed using covariates of a Cox regression analysis to assess survival and recurrence in patients with AEG. A two-sided P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All of the statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS package version 13.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States).

From January 2012 to June 2013, 55 patients including 48 males and 7 females (mean age 62.04 ± 7.44 years, range from 45 to 79 years) underwent surgical resection with curative intention for AEG according to the 7th UICC TNM classification of malignant tumors. Twenty patients had type II AEG, and 35 patients had type III AEG, according to Siewert’s classification. Patient demographics and tumor characteristics are presented in Table 1. With the exception of the tumor TNM stage and the histological type of tumor, both groups were comparable with regard to age, sex, Siewert type, pT status and lymph node metastasis status. According to the postoperative pathologic inspection, there were no cases of positive surgical margins, and the patients from both groups underwent R0 curative resections.

| Pathologic characteristic | ADTR (n = 18) | RY (n = 37) | P value |

| Sex ratio (Male:Female) | 17:1 | 31:6 | 0.406 |

| Age (yr) | 61.94 ± 6.41 | 62.08 ± 7.98 | 0.950 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.50 ± 2.61 | 20.98 ± 2.66 | 0.683 |

| Siewert type | 0.497 | ||

| II | 7 | 11 | |

| III | 11 | 26 | |

| pT status | 0.744 | ||

| T1a | 0 | 0 | |

| T1b | 3 | 3 | |

| T2 | 1 | 4 | |

| T3 | 2 | 5 | |

| T4a | 12 | 25 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.709 | ||

| pN0 | 6 | 8 | |

| pN1 | 4 | 9 | |

| pN2 | 7 | 15 | |

| pN3a | 1 | 5 | |

| pN3b | 0 | 0 | |

| Tumor TNM stage | 0.002 | ||

| Ia | 3 | 0 | |

| Ib | 2 | 0 | |

| IIa | 1 | 4 | |

| IIb | 1 | 6 | |

| IIIa | 3 | 3 | |

| IIIb | 7 | 7 | |

| IIIc | 1 | 17 | |

| Histological type | 0.002 | ||

| Well differentiated | 3 | 16 | |

| Moderately differentiated | 11 | 13 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 4 | 8 |

A total of 18 patients underwent surgical intervention by ADTR; the remaining 37 patients underwent RY reconstruction after total gastrectomy. The perioperative outcomes of the ADTR and RY groups are shown in Table 2. Comparing the perioperative outcomes between the ADTR and RY groups, there were no significant differences in terms of body mass index (BMI), postoperative length of hospital stay, operating time or intraoperative blood loss, whereas the time to first flatus in the ADTR group was significantly shorter than that in the RY group (2.94 ± 0.83 d vs 3.97 ± 1.11 d, P = 0.002). A similar outcome for the time to resuming a liquid diet was detected for the two groups (4.47 ± 1.28 d vs 6.11 ± 1.82 d, P = 0.001).

| Clinical feature | ADTR (n = 18) | RY (n = 37) | P value |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 12.88 ± 5.81 | 14.08 ± 5.85 | 0.495 |

| Operating time (min) | 282.22 ± 77.93 | 274.86 ± 63.23 | 0.709 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 362.77 ± 294.15 | 270.81 ± 148.22 | 0.601 |

| First flatus time (d) | 2.94 ± 0.83 | 3.97 ± 1.11 | 0.002 |

| Time to resume liquid diet (d) | 4.47 ± 1.28 | 6.11 ± 1.82 | 0.001 |

The median follow-up period for patients in the two groups was 17 mo (range 12-30 mo). In these patients, a comparison of the overall postoperative complication rate did not present a statistically significant difference. There were no differences in major complications, including anastomotic leakage, anastomotic stenosis, anastomotic hemorrhage, wound infection, respiratory infection, pleural effusion, lymphorrhagia, and other surgery-related complications, between the two groups. However, the incidence of reflux esophagitis was more common in the RY group compared with the ADTR group (Table 3).

| Complication | ADTR (n = 18) | RY (n = 37) | P value |

| Anastomosis-related complications | |||

| Anastomotic leakage | 1 | 0 | 0.148 |

| Anastomotic stenosis | 0 | 1 | 0.481 |

| Anastomotic hemorrhage | 0 | 0 | - |

| Early complications | |||

| Wound infection | 2 | 3 | 0.716 |

| Respiratory infection | 1 | 4 | 0.525 |

| Pleural effusion | 2 | 3 | 0.716 |

| Lymphorrhagia | 1 | 3 | 0.732 |

| Long-term complications | |||

| Reflux esophagitis | 0 | 6 | 0.048 |

| Cholelithiasis | 1 | 3 | 0.732 |

| Tumor recurrence | 1 | 6 | 0.266 |

| Tumor metastasis | 1 | 5 | 0.374 |

| Overall postoperative complication | 3 | 7 | 0.839 |

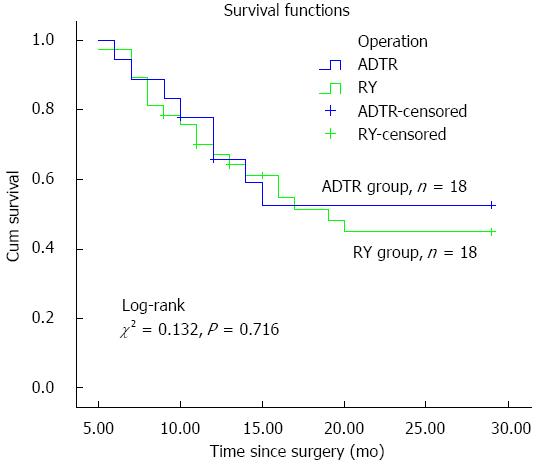

Regarding tumor recurrence and metastasis for patients’ long-term prognosis, no significant difference was identified between the two groups. Univariate Cox regression analysis of OS among AEG patients with operative intervention demonstrated that age, gender, BMI, pleural effusion, time to resuming a liquid diet, lymphorrhagia and TNM stage were prognostic factors for AEG in our study (Table 4). Meanwhile, multivariate Cox regression analyses confirmed that pleural effusion and lymphorrhagia had a significant effect on OS among AEG patients; however, BMI did not show a positive result for OS prognosis (Table 5). Furthermore, our follow-up data showed that the OS did not show a significant difference between the ADTR (55.6%) and RY (48.6%) groups (Figure 4).

| Characteristic | HR | 95%CI | P value |

| Age | 1.110 | 1.04-1.19 | 0.003 |

| Gender | 9.160 | 1.47-56.93 | 0.018 |

| BMI | 0.821 | 0.68-0.99 | 0.039 |

| Surgical method | 0.573 | 0.16-2.13 | 0.406 |

| Intraoperative blood loss | 1.000 | 0.99-1.01 | 0.496 |

| Length of postoperative hospital stay | 1.030 | 0.92-1.14 | 0.628 |

| Pleural effusion | 24.280 | 5.53-106.50 | < 0.001 |

| Time to first flatus | 0.685 | 0.49-0.96 | 0.448 |

| Time to resuming a liquid diet | 0.685 | 0.49-0.96 | 0.026 |

| Lymphorrhagia | 9.620 | 1.48-62.54 | 0.018 |

| TNM stage | 2.310 | 1.59-3.35 | < 0.001 |

| Characteristic | HR | 95%CI | P value |

| Age | 1.13 | 1.06-1.22 | 0.001 |

| Gender | 6.29 | 1.01-39.17 | 0.049 |

| Pleural effusion | 22.77 | 4.35-119.124 | < 0.001 |

| Time to resuming a liquid diet | 0.65 | 0.45-0.93 | 0.020 |

| Lymphorrhagia | 15.14 | 1.84-124.47 | 0.011 |

| TNM stage | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.982 |

| 2 | 0.02 | 0.01-0.350 | 0.003 |

| 3 | 0.19 | 0.01-0.651 | 0.146 |

| 4 | 0.05 | 0.01-0.484 | 0.007 |

| 5 | 0.03 | 0.01-0.446 | 0.009 |

| 6 | 0.43 | 0.16-1.13 | 0.087 |

Compared with other digestive tract tumors, AEGs pose numerous clinical controversies regarding histogenesis and clinicopathological characteristics as well as treatment strategies and prognosis. Surgical resection with en bloc tumor removal and regional lymphadenectomy is currently recommended as the mainstay of potentially curative therapy in the treatment of AEG. Meanwhile, concomitant postoperative complaints and complications such as delayed gastric emptying, reflux esophagitis, remnant gastritis or anastomositis, anastomotic ulcer, anastomotic stricture, and malnutrition seriously diminish patients’ postoperative quality of life. Hence, intraoperative digestive tract reconstruction methods play a vital role in minimizing postoperative complications for AEG patients. Therefore, the investigation of optimal reconstruction methods has been recognized as one of the main approaches to improving patients’ quality of life. The Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3) note that standard gastrectomy is the principal surgical procedure performed with curative intent; this treatment involves the complete resection of the stomach with D2 lymph node dissection. Proximal gastrectomy is adequate only for early gastric cancer (cT1cN0M) located in the upper third of the stomach[17,19,20]. Reconstruction methods for proximal gastrectomy are far less prevalent than for total gastrectomy. Digestive tract reconstruction options for total gastrectomy are clinically applied in more than 50% of cases; however, classical RY remains the optimal choice because there is a lack of high-level multi-center randomized controlled studies to generate evidence-based support for other methods. Whether RY with esophagojejunal anastomosis for total gastrectomy is the best solution for AEG remains controversial, and numerous problems must be addressed[21-24]. First, total gastrectomy implemented for AEG may be classified in the excessive resection range. For example, “the 13th Japanese Gastric Cancer statute” advocated that lymph nodes Nos. 5, 6, 12a, 12b and 14v should be regarded as third station lymph nodes (D3) that do not need to be removed for proximal gastric tumors. Second, it is important to determine whether the incidence of cholelithiasis and postoperative malnutrition will increase or whether bile secretion will decrease when the duodenal pathway is absent[25]. Third, total gastrectomy not only prevents gastric juice secretion from affecting the assimilation of iron and causing iron deficiency anemia (IDA) but also decreases intrinsic factor secretion, which impedes vitamin B12 absorption and causes megaloblastic anemia (MA), which ultimately results in post-gastrectomy malabsorption syndrome. Hence, we explored and improved a new method of digestive tract reconstruction involving ADTR and compared it to the classical Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy for total gastrectomy. We found that ADTR could commendably overcome the disadvantages of the RY method and enhance patients’ postoperative quality of life[12,26].

ADTR was first reported for proximal gastrectomy by Aikou et al[27] in 1988 and was confirmed to offer numerous advantages. ADTR offers a more reasonable resection region and lymphadenectomy, especially for the majority of patients undergoing total gastrectomy. The duodenal chymus pathway remains intact during ADTR, which stimulates gastrointestinal hormone secretion (such as pancreozymin, cholecystokinin, and insulin). As a result, ADTR retains the primordial digestive function and reduces the incidence of postoperative malnutrition and cholelithiasis[28].

Furthermore, the remnant gastric antrum provides the capacity for food storage, which not only delays emptying time to ensure the efficient mixing of food with the digestive juices but also promotes gastrin (GAS) secretion for adequate chymus digestion, ultimately enhancing patients’ long-term quality of life[29]. Moreover, ADTR provides double output channels for food transit, and this split transit approach can effectively prevent and reduce the incidence of esophageal reflux and dumping syndrome[29-31]. Additionally, the remnant gastric antrum maintains gastric hormone secretion, which partially aids in the absorption of iron and prevents malabsorption of vitamin B12, decreasing the incidence of post gastrectomy malabsorption syndrome.

The data for 55 AEG patients were retrospectively analyzed. Comparing the pathological characteristics between the ADTR and RY groups revealed no significant difference in terms of Siewert type, pT status or lymph node metastasis (pN). An advanced tumor TNM stage usually indicated a worse prognosis, whereas a well-differentiated histological type predicted a better prognosis. Although significant differences were shown with respect to the TNM stage and the degree of histological differentiation in our study, they had opposite trends and their effects could not be confirmed. In the ADTR group, the obvious advantages were observed for the time to first flatus (2.94 ± 0.83 d vs 3.97 ± 1.11 d, P = 0.002) and the time to resuming a liquid diet (4.47 ± 1.28 d vs 6.11 ± 1.82 d, P = 0.001). However, no differences were found with respect to perioperative outcomes, anastomosis-related complications or early complications between the two groups. Similarly, there were no statistically significant differences with respect to tumor recurrence or metastasis during the follow-up period (range, 12-30 mo). The Kaplan-Meier graph showing OS according to operative procedure between the two groups also demonstrated similar outcomes (Figure 4), which confirmed that ADTR was technically safe and feasible, compared with conventional Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy after total gastrectomy.

Based on the outcome of the Cox regression analysis, our study revealed that age, gender, BMI, pleural effusion, time to resuming a liquid diet, lymphorrhagia, and TNM stage were important prognostic factors for OS in this setting. Hence, we conclude that ADTR may be suitable to improve the quality of life and OS of AEG patients. It was found that pleural effusion and lymphorrhagia play an important role in prognosis and OS, and extensive surgical intervention is required to decrease these complications. In our opinion, redundant or rough posterior mediastinum anatomy might cause pleura injury and result in pleural effusion, which together with lymphorrhagia, mainly caused by uncompleted lymph-vessel ligature, seriously affected the OS of AEG patients. Therefore, elaborate anatomy around the cardia and sufficient ligature were recommended to improve the OS of AEG patients. In addition, we observed that an early return to a liquid diet could afford patients better quality of life. Notably, intraoperative blood loss did not affect the prognosis of AEG. One possible explanation is that we transfused sufficient blood products to avoid hypovolemia and its corresponding factors. With respect to tumor recurrence, metastasis and long-term survival, there were no differences between the ADTR group and the RY group. These results confirmed that the ADTR method is a safe and reasonable reconstruction procedure.

In conclusion, the ADTR approach is recommended over traditional Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy for Siewert types II and III AEG. Although ADTR provides similar rates of tumor recurrence, metastasis and long-term survival, this approach considerably improves the near-term quality of life, especially in terms of early recovery and decreased reflux esophagitis. Therefore, ADTR is recommended as a worthwhile digestive tract reconstruction approach.

We are grateful to our patients and the staff involved in managing the patients for making this study possible.

The incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction (AEG) is rising rapidly and surgery remains the only established curative treatment for AEG in its resectable stages. However, the alimentary canal reconstruction method, which plays a determining factor in postgastrectomy quality of life among AEG patients, has not been established. To explore a reasonable reconstruction method for AEG patient, the authors developed a new reconstruction method, antrum-preserving double tract reconstruction (ADTR), and assessed its efficacy and safety in terms of long-term survival, complication morbidity, and mortality retrospectively at our institution since January 2012.

With the development of standard surgery for AEG, gastrointestinal surgeons have taken an increased interest in optimal digestive tract reconstruction pattern which not only provides radical tumor removal but also alleviates the surgery-related complications as soon as possible and offers satisfying quality of life.

The present study modified the double-track anastomosis for alimentary canal reconstruction after radical proximal gastrectomy by combining the advantages of Roux-en-Y and functional reconstruction of the stomach with jejunal interposition, which preserves the antrum so that chyme can be thoroughly mixed prior to transit to the duodenal passage and reduces the morbidity of backflow sequelae by offering an adequate evacuation tract. Thus, the procedure ADTR obviously shortened the perioperative recovery indexes such as time to first flatus and time to resuming a liquid diet. The postoperative morbidity and mortality rates for overall postoperative complications and the rates of tumor recurrence and metastasis were not significantly different between the two groups.

The study suggests that ADTR is technically safe and feasible, offering an agreeable near-term quality of life, especially in terms of early recovery and the alleviation of reflux esophagitis. ADTR may be a worthwhile digestive tract reconstruction method for Siewert types II and III AEG.

The present study provides a practical and well-illustrated review of the safety and feasiblility of ADTR for AEG. Based on the experience with 55 AEG patients, the conclusion is that ADTR is technically safe and feasible, with acceptable surgical outcomes.

P- Reviewer: Tiberio G S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Buas MF, Vaughan TL. Epidemiology and risk factors for gastroesophageal junction tumors: understanding the rising incidence of this disease. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2013;23:3-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mariette C, Piessen G, Briez N, Gronnier C, Triboulet JP. Oesophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma: which therapeutic approach? Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:296-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hasegawa S, Yoshikawa T. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: incidence, characteristics, and treatment strategies. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13:63-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chung JW, Lee GH, Choi KS, Kim DH, Jung KW, Song HJ, Choi KD, Jung HY, Kim JH, Yook JH. Unchanging trend of esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma in Korea: experience at a single institution based on Siewert’s classification. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:676-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Huang Q. Carcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction in Chinese patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:7134-7140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Deans C, Yeo MS, Soe MY, Shabbir A, Ti TK, So JB. Cancer of the gastric cardia is rising in incidence in an Asian population and is associated with adverse outcome. World J Surg. 2011;35:617-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | MacDonald WC. Clinical and pathologic features of adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia. Cancer. 1972;29:724-732. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Stein HJ, Feith M, Siewert JR. Cancer of the esophagogastric junction. Surg Oncol. 2000;9:35-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McColl KE, Going JJ. Aetiology and classification of adenocarcinoma of the gastro-oesophageal junction/cardia. Gut. 2010;59:282-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Whitson BA, Groth SS, Li Z, Kratzke RA, Maddaus MA. Survival of patients with distal esophageal and gastric cardia tumors: a population-based analysis of gastroesophageal junction carcinomas. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:43-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Classification of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1457-1459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 876] [Cited by in RCA: 914] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Maksimovic S. Double tract reconstruction after total gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer: our experience. Med Arh. 2010;64:116-118. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Jiang X, Hiki N, Nunobe S, Fukunaga T, Kumagai K, Nohara K, Katayama H, Ohyama S, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Long-term outcome and survival with laparoscopy-assisted pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1182-1186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yoo CH, Sohn BH, Han WK, Pae WK. Proximal gastrectomy reconstructed by jejunal pouch interposition for upper third gastric cancer: prospective randomized study. World J Surg. 2005;29:1592-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in RCA: 1895] [Article Influence: 135.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Biondi A, Hyung WJ. Seventh edition of TNM classification for gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4338-4339; author reply 4340-4342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2872] [Article Influence: 205.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumours. 7th ed. New York: Wiley-Blackwell 2009; . |

| 19. | Matsuda T, Takeuchi H, Tsuwano S, Nakahara T, Mukai M, Kitagawa Y. Sentinel node mapping in adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. World J Surg. 2014;38:2337-2344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hasegawa S, Yoshikawa T, Rino Y, Oshima T, Aoyama T, Hayashi T, Sato T, Yukawa N, Kameda Y, Sasaki T. Priority of lymph node dissection for Siewert type II/III adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:4252-4259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hiki N, Nunobe S, Kubota T, Jiang X. Function-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2683-2692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Barbour AP, Lagergren P, Hughes R, Alderson D, Barham CP, Blazeby JM. Health-related quality of life among patients with adenocarcinoma of the gastro-oesophageal junction treated by gastrectomy or oesophagectomy. Br J Surg. 2008;95:80-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schiesser M, Schneider PM. Surgical strategies for adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2010;182:93-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Amenabar A, Hoppo T, Jobe BA. Surgical management of gastroesophageal junction tumors. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2013;23:16-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nomura E, Lee SW, Kawai M, Yamazaki M, Nabeshima K, Nakamura K, Uchiyama K. Functional outcomes by reconstruction technique following laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: double tract versus jejunal interposition. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Namikawa T, Kitagawa H, Okabayashi T, Sugimoto T, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K. Double tract reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer is effective in reducing reflux esophagitis and remnant gastritis with duodenal passage preservation. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:769-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Aikou T, Natsugoe S, Shimazu H, Nishi M. Antrum preserving double tract method for reconstruction following proximal gastrectomy. Jpn J Surg. 1988;18:114-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Sakuramoto S, Yamashita K, Kikuchi S, Futawatari N, Katada N, Moriya H, Hirai K, Watanabe M. Clinical experience of laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy with Toupet-like partial fundoplication in early gastric cancer for preventing reflux esophagitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:344-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cordesmeyer S, Lodde S, Zeden K, Kabar I, Hoffmann MW. Prevention of delayed gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy with antecolic reconstruction, a long jejunal loop, and a jejuno-jejunostomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:662-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Cook MB, Corley DA, Murray LJ, Liao LM, Kamangar F, Ye W, Gammon MD, Risch HA, Casson AG, Freedman ND. Gastroesophageal reflux in relation to adenocarcinomas of the esophagus: a pooled analysis from the Barrett’s and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Consortium (BEACON). PLoS One. 2014;9:e103508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kim J, Kim S, Min YD. Consideration of cardia preserving proximal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer of upper body for prevention of gastroesophageal reflux disease and stenosis of anastomosis site. J Gastric Cancer. 2012;12:187-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |