Published online Jul 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i26.7970

Peer-review started: January 30, 2015

First decision: March 10, 2015

Revised: March 27, 2015

Accepted: May 2, 2015

Article in press: May 4, 2015

Published online: July 14, 2015

Processing time: 165 Days and 5.2 Hours

Ampullary neoplasms, although rare, present distinctive clinical and pathological features from other neoplastic lesions of the periampullary region. No specific guidelines about their management are available, and they are often assimilated either to biliary tract or to pancreatic carcinomas. Due to their location, they tend to become symptomatic at an earlier stage compared to pancreatic malignancies. This behaviour results in a higher resectability rate at diagnosis. From a pathological point of view they arise in a zone of transition between two different epithelia, and, according to their origin, may be divided into pancreatobiliary or intestinal type. This classification has a substantial impact on prognosis. In most cases, pancreaticoduodenectomy represents the treatment of choice when there is an overt or highly suspicious malignant behaviour. The rate of potentially curative resection is as high as 90% and in high-volume centres an acceptable rate of complications is reported. In selected situations less invasive approaches, such as ampullectomy, have been advocated, although there are some concerns mainly because of a higher recurrence rate associated with limited resections for invasive carcinomas. Importantly, these methods have the drawback of not including an appropriate lymphadenectomy, while nodal involvement has been shown to be frequently present also in apparently low-risk carcinomas. Endoscopic ampullectomy is now the procedure of choice in case of low up to high-grade dysplasia providing a proper assessment of the T status by endoscopic ultrasound. In the present paper the evidence currently available is reviewed, with the aim of offering an updated framework for diagnosis and management of this specific type of disease.

Core tip: In this paper we review current evidence regarding ampullary neoplasm, with a particular focus on diagnosis and treatment. We are providing a framework for management of these neoplasms that, although rare, display distinctive clinical features. Current evidence about optimal management is reviewed, outlining the role of surgery as compared to newer endoscopic techniques: indeed, while surgery is mandatory for invasive carcinomas due to possible nodal involvement, endoscopy should be considered for non-invasive lesions.

- Citation: Panzeri F, Crippa S, Castelli P, Aleotti F, Pucci A, Partelli S, Zamboni G, Falconi M. Management of ampullary neoplasms: A tailored approach between endoscopy and surgery. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(26): 7970-7987

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i26/7970.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i26.7970

Neoplasms of the ampulla of Vater account for only 0.5% of all gastrointestinal malignancies[1]. Although ampullary carcinomas are rare neoplasms, they occur more frequently in the ampullary region than elsewhere in the small intestine[2]. The papilla is a nipple-like structure on the medial aspect of the second portion of the duodenum, best visualized with a side-viewing endoscope. Ampullary carcinomas are defined as gland-forming malignant epithelial neoplasms, which originate in the ampullary complex, distal to the bifurcation of the common bile duct and the pancreatic duct[3].

One of the possible causes of developing neoplasms in this area is that the ampullary region contains a transition from pancreatobiliary to intestinal epithelium, and such areas of transition are inherently unstable. As observed by Cattell and Pyrtek in 1949, the ampullary region is “an area of epithelium transition which is constantly being irritated chemically and mechanically”[4].

The appropriate diagnosis of ampullary neoplasms can be challenging and nowadays different diagnostic modalities can be considered including high-resolution imaging techniques, endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)[5].

As a matter of fact, there are no specific guidelines for the diagnosis of these neoplasms. Usually ampullary neoplasms are incorporated into the guidelines of biliary tract[6] or pancreatic carcinomas[7].

Regarding treatment, the first local resection of an ampullary lesion was reported in 1898 and the first radical resection (pancreaticoduodenectomy - PD) in 1912. The latter approach resulted in a reduced risk of recurrence, even if it maintains still nowadays high morbidity rates. In 1993 Binmoeller[8] reported the first endoscopic resection of the ampulla with a curative intent. This procedure is technically demanding, but in the last 20 years advances in endoscopic procedures with ablative techniques (such as mono, bi and argon plasma coagulation) as well as pancreatic and biliary stenting led to a low morbidity and mortality risk. Indeed endoscopic ampullectomy is the procedure of choice for ampullary adenomas and can be chosen as an alternative procedure in patients not eligible for surgery. The aim of this paper is to provide a review of the modern diagnostic tools and different treatments for ampullary neoplasms, including both endoscopic and surgical approaches.

The vaterian system is located in the wall of the second part of the duodenum, at the confluence of the common bile duct and the major pancreatic duct. It includes the duodenal papilla (a mucosal elevation into duodenal lumen), Oddi’s sphincter muscle, a fibrous covering and the ampulla of Vater. A true ampulla, defined as a dilated reservoir into which the ducts empty, is an infrequent finding (3%): indeed there are several anatomical variations in the connection between the two ducts.

In consideration of the anatomical characteristics we reported above, it is very difficult to localize the precise origin of tumors once they have invaded adjacent tissue[2].

The cancer of the ampulla is a rare disease with an incidence of less than one per 100000; in autopsy series, ampullary neoplasms are seen in 0.06%-0.21% of the general population[3].

In a large series of 5625 patients with cancer of the ampulla, 10% of cases had a previously reported primary cancer in another anatomic site, while in 90% of patients the ampullary lesion was the initial primary neoplasm[9].

In the same study, women were found to be less frequently affected (0.36/100000) than men (0.56/100000, P < 0.05). The disease is also more common in Caucasians than in Afro-Americans.

In the study by Albores-Saavedra et al[9] an increase of ampullary cancer incidence from 1973 to 2005 has been reported, with an annual percentage rate of 0.9%.

The rates of incidence of the various histological subtypes of ampullary cancer have been approximately the same across all ages group, suggesting similar or overlapping carcinogenic pathways. In all of the histological types surveyed, cancer was found predominantly in the older age groups. According to the age-specific rates, the incidence of cancers of the ampulla began to increase after age 30, but increased more rapidly after age 50 in both men and women; average age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 for sporadic forms.

Although ampullary cancers are generally sporadic, some hereditary syndromes are associated with a higher risk for this type of cancer. The strongest predisposition for ampullary neoplastic disease is represented by the familiar adenomatous polyposis (FAP) syndrome. FAP patients frequently develop duodenal adenomas and their risk of periampullary cancer is 100%-200% higher compared to the general population; this results in a prevalence of ampullary cancer of 3%-12%[10]. Compared to sporadic cases, familiar cases of ampullary cancer also tend to present at a younger age.

Obstructive jaundice is the most common presenting symptom of ampullary cancer (85%)[11-13], caused by compression of the distal bile duct by the tumor. In contrast to biliary obstruction due to passage of calculi, in ampullary neoplasms jaundice is usually persistent rather than intermittent and may be accompanied by a distended, palpable gallbladder (Courvoisier’s sign), that is however an uncommon finding (only 15% of cases). Gallstones are present in one third of patients, which may lead to misdiagnosis[14]. Presence of jaundice is associated with advanced stage of disease and increased risk of tumor recurrence after resection[15-20]. Other common symptoms include weight loss, fatigue and abdominal pain which are present in more than half of patients[21]. Acute pancreatitis is less frequent, but ampullary cancer should be ruled out in this case[22]. Up to one-third of patients have chronic, frequently occult, gastrointestinal blood loss but occasionally frank bleeding may occur[23]. Rarely, large lesions may produce gastric outlet obstruction.

Serum CA 19-9 is elevated in 86.4% of ampullary carcinoma patients[24].

Because of their location, at the time of diagnosis ampullary carcinomas are often small[25] (at presentation 17% are less than 1 cm[26], 23% are less than 2 cm and 75% are less than 4 cm[27]) Despite their small size, the common bile duct is almost always dilated and the pancreatic duct is dilated as well in half of the patients[2]. As a collateral remark, this mismatch between tumor size and biliary obstruction explains why, compared to pancreatic cancers, resectability at presentation is significantly higher (70%-80% vs 10%-25%)[28,29].

Several classifications of ampullary carcinomas have been developed according to their gross appearance based on duodenal aspect or extension of neoplasm. Three distinct categories of carcinomas are recognized, after the correlation of gross and microscopic features: (1) intra-ampullary neoplasms, characterized by a prominent intraluminal growth of the pre-invasive neoplasms, which frequently protrude into the duodenal lumen from a patulous orifice of the papilla of Vater; (2) peri-ampullary, with prominent exophytic, ulcerous-vegetating components on the duodenal surface of the ampulla. The ulcerating part frequently corresponds to the invasive component, whereas the vegetating part represents the pre-invasive component; and (3) mixed exophytic and mixed ulcerated lesions[2,30,31]. The Presence of ulcerations is associated with poor survival rate[32].

The complex histological structure of the papilla of Vater gives rise to a heterogeneous group of neoplasms with different histologic types, classified according to the predominant component.

Kimura et al[33] were the first to demonstrate that adenocarcinomas originating in the ampulla of Vater may be divided in two subsets according to their type of differentiation, which can be either “intestinal” or “pancreatobiliary”.

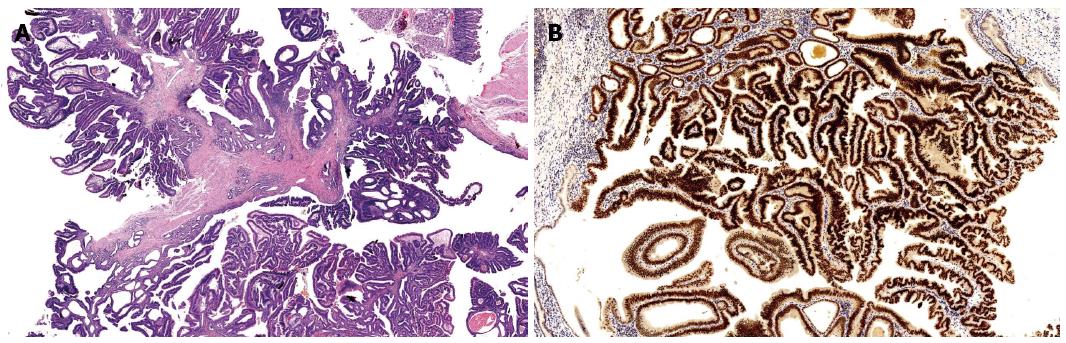

The intestinal type, the most common invasive sub-type, is characterized by tubular or cribriform glands similar to those of colon-rectal adenocarcinomas. Incidence of this subtype is reported with a wide variability in different case studies (25%-78%)[2,33-36]. Most cases are associated with areas of residual adenoma, within the ampulla and in the surrounding duodenal mucosa. The adenocarcinomas arising in an adenoma (adenocarcinoma in villous adenoma, in tubulo-villous adenoma, in adenomatous polyp, and villous adenocarcinoma), are usually smaller and show a better prognosis. They show intestinal type immunophenotype, with the expression of keratin 20, MUC2 and CDX2[37,38] (Figure 1).

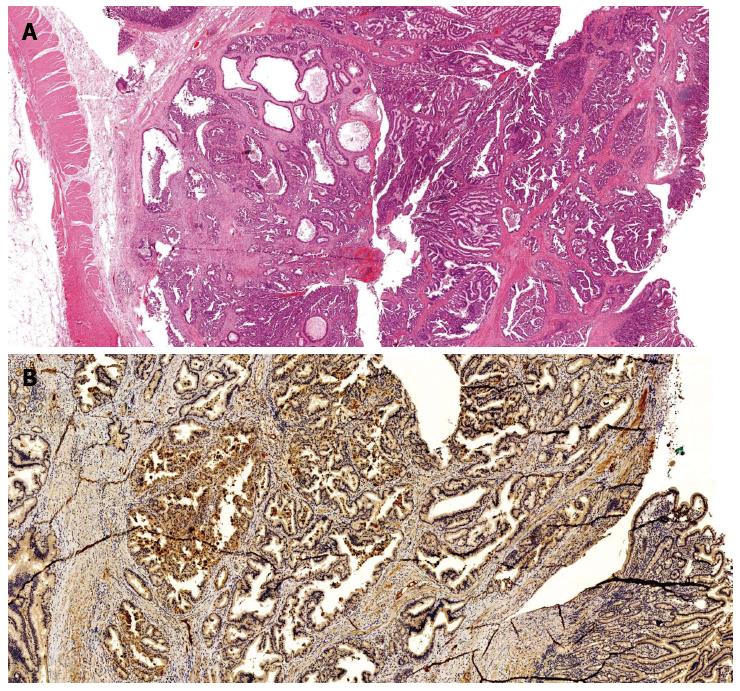

The pancreatobiliary type adenocarcinomas closely resemble primary tumors of the pancreas or extra hepatic bile ducts and represent 22%-74% of ampullary adenocarcinomas[2,33-36]. They are composed of glands associated with an abundant desmoplastic stroma, and stain positively for MUC1, MUC 5a and CK7[37,38] (Figure 2). Pancreatobiliary carcinomas have a worse prognosis, being frequently associated with unfavourable histopathologic features, such as lymph node invasion, perineural infiltration or areas of poor differentiation[25,28,33,39-42].

Some ampullary adenocarcinomas may exhibit mixed features of both intestinal and pancreatobiliary type; the distinction between the two patterns may be difficult in less differentiated cases.

Although closely related to the conventional type, distinct variants of adenocarcinomas include[43]: (1) adeno-squamous carcinoma: a malignant neoplasm composed of a mixture (> 30%) of two neoplastic components, a glandular and a squamous cell component; (2) colloid carcinoma[44] characterized by the presence of mucin-producing neoplastic cells (that should comprise at least 80% of the lesion) floating in large pools of extracellular mucin. Since the vast majority of colloid carcinomas of the ampulla express the intestinal markers CDX2 and MUC2, these tumours are regarded as variants of intestinal-type adenocarcinomas; (3) signet-ring cell carcinoma[9]: highly malignant neoplasm predominantly composed of infiltrating non-cohesive cells with intra-cytoplasmic mucin, which displaces the nucleus towards the periphery, creating the signet ring cell appearance. Cells may be associated with extracellular mucin but the large pools seen in colloid carcinoma are lacking. Since this entity is very rare, metastases from other more common signet cell carcinomas, mammary or gastric, should be ruled out; (4) undifferentiated carcinoma: highly aggressive neoplasm without a definite direction of differentiation. They can occur ex-novo or be associated with other ampullary neoplasms. They are usually large and widely invasive. The spectrum of morphology varies from highly cellular, pleomorphic epithelioid mononuclear cells with abundant cytoplasm, often admixed with bizarre multinucleated giant cells to relatively monomorphic epithelioid and spindle; (5) papillary adenocarcinoma[45]: they may show a non-invasive papillary component and an invasive carcinoma. The invasive carcinomas show either pancreatobiliary or intestinal phenotype; and (6) neuroendocrine carcinoma[46]: characterized by either small or large neuroendocrine-cells, grade 3 (G3). Their histological features and prognosis resemble those of their pulmonary counterparts.

According to the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program[9], well and moderately differentiated carcinomas (grade I-II) predominated over high-grade carcinomas (grade III-IV), with a frequency of 15.6% and 33.6% for grade I and II respectively, as opposed to 20.8% and 1.4% for grade III and IV, respectively.

The 2010 AJCC staging system is reported in Table 1[47]. The T classification depends on the extension of the primary neoplasm: local spread begins from within the ampulla of Vater and the sphincter of Oddi (T1), then extends into the duodenal wall (T2) or beyond, into the head of the pancreas (T3) or contiguous soft tissue or organs (T4)[48].

| T = Primary Tumor | |||

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | ||

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | ||

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ | ||

| T1 | Tumor limited to ampulla of Vater or sphincter of Oddi | ||

| T2 | Tumor invades duodenal wall | ||

| T3 | Tumor invades pancreas | ||

| T4 | Tumor invades peripancreatic soft tissue or other adjacent organs or structures other than pancreas | ||

| N = Regional Lymph Nodes | |||

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | ||

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | ||

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis | ||

| M = Distant Metastasis | |||

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed | ||

| M0 | No distant metastasis | ||

| M1 | Distant metastasis | ||

| G = Histologic Grade | |||

| GX | Grade cannot be assessed | ||

| G1 | Well differentiated | ||

| G2 | Moderate differentiated | ||

| G3 | Poorly differentiated | ||

| G4 | Undifferentiated | ||

| Stage | T | N | M |

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| IA | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| IB | T2 | N0 | M0 |

| IIA | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| IIB | T1 | N1 | M0 |

| T2 | N1 | M0 | |

| T3 | N1 | M0 | |

| III | T4 | Any N | M0 |

| IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

Regional lymph nodes include the peripancreatic lymph nodes (superior and inferior pancreatic head nodes; anterior and posterior pancreatico-duodenal nodes) and the lymph nodes along the hepatic artery, proximal mesenteric artery, celiac axis and pyloric regions. Optimal histological examination of pancreaticoduodenectomy specimen should include analysis of a minimum of 12 lymph nodes[47].

Metastatic lymph nodes are found in 28% to 60% (Table 2) of resected ampullary carcinomas[49]. Tumors that invaded the duodenal submucosa showed regional lymph node involvement in 42% of cases, while metastatic disease was almost never found with tumors limited to the mucosa or to the sphincter of Oddi[48]. Cannon et al reported an incidence of node metastasis respectively of 0%, 46%, 50% and 100% in T1, T2, T3 and T4. While it has been consistently confirmed that T stage is an important predictor of nodal status, many other Authors have instead observed nodal metastases also in T1 tumors, with a frequency ranging from 10% to 50%[16,50-53]. This observation is particularly important for surgical management of these lesions, as we will discuss in the section about treatment.

| Ref. | n/resected | Operative mortality (%) | Positive nodes (%) | R0 (%) | Pancreatobil/intestinal, n (%) | Survival-resected | Median survival - resected (mo) | Predictors of worse survival or recurrence | |

| 5 yr | 10 yr | ||||||||

| Albagli et al[128] | 50/50 | 8.0 | 36.0 | - | - | N0 52% | - | - | None |

| N+ 39% | |||||||||

| Allema et al[136] | 67/67 | 1.5 | 52.0 | 75.0 | - | 50% | - | R+ | |

| Beger et al[50] | 171/171 | 3.1 | 54.0 | 79.6 | - | N+ 21% | - | - | N+2, Pan+, R, Stage2, G2-3 |

| N0: 63% | |||||||||

| Bettschart et al[18] | 88/70 | 0.0 | 40.0 | 97.2 | 37.91 | 45.8 | Bilirubin2, Age > 70, G3, N+2, Neu+, Pan+ | ||

| Brown et al[91] | 72/51 | 2.0 | 47.0 | 100.0 | - | 58% | N+2, T, G | ||

| Carter et al[137] | 157/145 | - | 33.0 | 86.0 | 53 (45)-54 (46) | - | - | - | Pancreatobil2, Bilirubin, Stage2, N+, T, Ly+2, Neu+2 |

| Chareton et al[35] | 63/51 | 7.5 | - | - | - | 40% | - | Stage, Ampullectomy | |

| Choi et al[129] | 78/70 | 2.6 | 31.4 | 95.7 | - | 59.90% | 29% | 70 | Jaundice, Ulcerated, Pan+, G |

| N0 63.5% | |||||||||

| N+ 50.8% | |||||||||

| Di Giorgio1 et al[138] | 94/64 | 8.6 | 28.0 | 100.0 | - | 64.4% | 54 | No resection , Size, G, Depth of infiltration2 | |

| Duffy et al[92] | 55 | 0.0 | 41.8 | 98.2 | - | 67.70% | - | - | Neu+2 |

| Falconi et al[19] | 90/90 | 4.0 | 48.0 | 61% (disease free) | Stage, T, LNR2 | ||||

| Hornick et al[16] | 157/150 | 59.8 | Adenocarcinoma 45% | Jaundice, Stage, N+ | |||||

| 106 | Adenoma 82% | ||||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | N+ 47% | ||||||||

| N0 63% | |||||||||

| Howe1 et al[28] | 123/101 | 5.0 | 45.5 | 96.1 | - | 46% | - | 58.8 | No resection, N+2, R+2, G3 |

| Iacono et al[139] | 59/59 | 7.8 | 37.3 | - | - | 46% | 33% | 31 | G, T2, N+, Chromosome 17p2, 18q2, Micro satellite instab., Standard PD |

| Inoue et al[140] | 34/34 | 52.6% | N+2, Pan+, V+2, Neu+2, SMA2 | ||||||

| Kawaguchi et al[141] | 28/28 | 56.4% | 37 | Duo+, Ly+, V+2 | |||||

| Kim et al[34] | 104/104 | 39.4 | 62 (60)-42 (40) | 60.1% | 57.6% | T2, CEA, N+2, G32, Pancreatobil2, Neu+, Ly+ | |||

| Kimura et al[36] | 51 | - | 45.0 | - | 38 (74)-13 (25) | Pancreatobil | |||

| Klempnauer et al[142] | 94/94 | 9.6 | 38.0 | 97.0 | - | 34.5% | 28.6% | - | Size2, G3, N+, Stage |

| Lazaryan et al[20] | 72/72 | - | 34.0 | 96.0 | - | 61% | - | - | Neu+2, Ulcerated2, N+2, Stage, Weight loss |

| Norero et al[143] | 50/50 | 32% | 28 | N+2 | |||||

| Ohike et al[134] | 244/244 | - | 38.0 | 95.0 | 162 (66) other | 33% | - | - | Budding2, N+2, T2, R+2 |

| 82 (34) intestinal | Hi budding 24% | ||||||||

| Low budding 68% | |||||||||

| Qiao et al[59] | 127/127 | 9.7 | 35.0 | 98.4 | 43.3% | 35.7% | N+2, T2, Stage, Pan+ | ||

| Roder et al[144] | 69/66 | 4.5 | 42.0 | - | - | 35% | - | 41 | N(nr) |

| Sakata et al[130] | 71/71 | 0.0 | 48.0 | 97.2 | 64% | 55% | G, Pan+, Ly+2, V+2, Neu+, R+, N+2, LNR | ||

| Shinkawa et al[145] | 23/23 | 52% | 32% | Pan+, N+ | |||||

| Talamini1 et al[51] | 120/106 | 3.8 | 40.0 | - | - | 38% | - | 46 | No resection, Transfusion2, N+, G2-3 |

| N+ 31% | |||||||||

| N0 43% | |||||||||

| Todoroki et al[95] | 66/59 | 0.0 | 60.0 | 93.2 | - | 52.6% | R+, CEA, Ulcerated, T2, N+, Stage2, Ly+2, V+ | ||

| Westgaard et al[25] | 114/114 | 3.5 | 57.0 | 65.0 | 67 (59)-47 (41.2) | - | Pancreatobil2, N+2, V+2 | ||

| 41 ampullary | Size2 | ||||||||

| Winter et al[127] | 450/450 | 2.0 | 54.5 | 96.1 | Adenocarcinoma 45% | N+ 23.4 | N+2, Neu+2, Transfusion2 | ||

| Adenoca: 347 | Adenoma 86% | N0 79 | |||||||

| N+ 35% | |||||||||

| N0 56% | |||||||||

| Yokoyama et al[15] | 74/59 | - | 53.5 | 100.0 | - | 61.0% | 53% | - | Pan+2, N+2, Jaundice, V+, Ly+2, Neu+, G |

| Zhao et al[146] | 105/105 | 8.6 | 37.1 | 42.8% | Pan+, Size2, T, TNM stage, N(nr)2 | ||||

In particular, lymph node involvement was significantly more common for pancreatico-biliary type tumors (55% vs 18% for intestinal type)[36], neuroendocrine carcinomas (57%)[54] and poorly differentiated carcinomas[2]. Metastasis to lymph nodes outside the regional groups described above, such as nodes of the pancreas tail or para-aortic ones, is considered as metastatic disease (M1).

Metastases (< 10% at presentation)[55] are commonly found in the liver and peritoneum and are less frequently seen in lungs and pleura.

In 35% to 80% of cases lymphatic and blood vessel involvement is encountered, while perineural invasion occurs less frequently[28,48].

Compared to the previous one, the new stage classification has been modified according to new prognostic information; nodal positivity is included in stage IIB, while stage III comprises patients with extensive (T4) tumors, with or without nodal disease. Stage I has now been divided into two subsets: IA, including tumors limited to the ampulla of Vater or sphincter of Oddi, and IB, indicating cancers that invade the duodenal wall. Similarly, stage II has been split into IIA, indicating tumors that invade the pancreas (T3), and IIB, which include T1-3 tumors with nodal disease. Stage IV is represented by metastatic tumors[56].

Following surgical resection, recurrence may occur locally (involving the tumor bed or the para-aortic lymphatics)[57] or at a distant site. Peripancreatic lymph nodes are the most frequent site of nodal involvement and, compared to pancreatic carcinoma, disease is more likely to be limited to this region. The spreading of ampullary carcinoma generally follows a halsteadian progression: nodal involvement manifests first, followed by appearance of liver metastases and subsequently distant dissemination.

Some data suggest a preferential lymphatic drainage flow from posterior pancreatico-duodenal lymph nodes to nodes located around the superior mesenteric artery, thereby underlining the importance of nodal dissection at least in these areas[32].

In the diagnostic evaluation of jaundiced patients with suspected malignant bile duct obstruction, benign tumors, inflammatory diseases and gallstones must be excluded first. Then the extent of tumor invasion and spread has to be established. During the diagnostic workup, another issue is to differentiate primary ampullary carcinoma from the more common periampullary tumors, including pancreatic, duodenum and bile duct carcinomas. In most cases, the distinction is not essential from a surgical point of view because, if a malignant lesion is suspected in that area, the patients will undergo the same operation (pancreaticoduodenectomy). However ampullary and periampullary tumors have substantially different oncologic implications and prognosis.

In the evaluation of patients with jaundice trans abdominal ultrasonography should be the first imaging study, since it can identify intra and extra hepatic bile duct dilatation, a distended gallbladder and gallstones; however the ampullary tumor may not be visualized[58]. As shown in Table 3, Ultrasound (US) sensitivity rate in tumor detection ranges from 5% to 15%[5,59-61], however indirect signs may be present in up to 70% of cases[60]. Due to low sensitivity of US, it is necessary not to underestimate indirect signs and to maintain a high level of suspicion. US evaluation in any case can give a clue to choosing the next most appropriate diagnostic exam: if a cystic mass is detected MRCP should be preferred. CT scan must be chosen if the mass is solid, whilst when no masses are identified (eco)endoscopy (EUS) must be performed.

| Ref. | n | Test | Tumor detection | T | N | Resectability | ||||||

| Sens | Spec | Acc | Acc | Sens | Spec | Acc | Sens | Spec | Acc | |||

| Artifon et al[147] | 27 | CT | - | - | - | 51.8% | 40.0% | 65.0% | 55.5% | - | - | - |

| EUS | - | - | - | 74.1% | 70.0% | 88.0% | 81.4% | - | - | - | ||

| Buscail et al[148] | 6 | EUS | - | - | - | 83.0% | - | - | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100% | 100% |

| Cannon et al[79] | 50 | CT | - | - | - | 24.0% | - | - | 59.0% | - | - | - |

| MRI | - | - | - | 46.0% | - | - | 77.0% | - | - | - | ||

| EUS | - | - | - | 78.0% | - | - | 68.0% | - | - | - | ||

| Chen et al[61] | 19 | US | 5.0% | - | - | 11.0% | 7.0% | - | - | - | - | - |

| CT | 21.0% | - | - | 22.0% | 33.0% | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| EUS | 95.0% | - | - | 72.0% | 47.0% | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Chen et al[5] | 41 | US | - | - | 12.2% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CT | - | - | 28.6% | 26.1% | 0.0% | - | 44.0% | - | - | - | ||

| MRI | - | - | 81.3% | 53.8% | 25.0% | - | 77.0% | - | - | - | ||

| EUS | - | - | 97.6% | 72.7% | 47.0% | - | 67.0% | - | - | - | ||

| Heinzow et al[84] | 72 | IDUS | 87.5% | 92.5% | 90.2% | - | - | - | 75.0% | - | - | - |

| ETP | 68.7% | 100.0% | 86.0% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| IDUS +ETP | 97.0% | 100.0% | 94.5% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Howard et al[149] | 21 | CT | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 63.0% | 100% | 86% |

| EUS | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 75.0% | 77% | 76% | ||

| Kubo et al[85] | 35 | EUS | - | - | - | 74.0% | - | - | 63.0% | - | - | - |

| Manta et al[82] | 24 | MRI | 75.0% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| EUS | 100.0% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Midwinter et al[63] | 34 | CT | 76.0% | - | - | - | 33.0% | 86.0% | - | - | - | - |

| EUS | 97.0% | - | - | - | 44.0% | 93.0% | - | - | - | - | ||

| Mukai et al[83] | 23 | EUS | 96.0% | - | - | 78.0% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Qiao et al[59] | 127 | US | 7.9% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CT | 19.0% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Rösch et al[64] | 28 | US | 7.0% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CT | 29.0% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| EUS | 93.0% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Skordilis et al[60] | 20 | US | 15.0% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CT | 20.0% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| EUS | 100.0% | - | - | 82.0% | - | - | 71.0% | - | - | - | ||

| Tio et al[150] | 32 | EUS | - | - | - | 84.4% | 68.8% | 37.5% | 53.1% | - | - | - |

Abdominal CT is more sensitive than US for evaluating the periampullary region, since it is not limited by the presence of bowel gas or obesity and is less operator-dependent. On the other hand, its diagnostic accuracy is not very high for small ampullary masses, especially if they are located within the duodenal wall or in the lumen. For the previous reasons, CT scan sensitivity is highly variable according to different reports ranging from 19% to 69%[5,60,62]. As shown in Table 3 CT specificity in tumor detection also varies widely, from 20% to 76%[60,61,63,64], while accuracy is only 28.6% as reported by Chen et al[5]. In order to maximize CT sensitivity, i.v. contrast medium should always be used in order to obtain arterial and venous phase imaging and water should be administered as oral contrast agent to distend the duodenum[2]. A bulging papilla can be encountered in healthy individuals as well as in patients with inflammatory diseases (papillitis from passage of biliary stones, parasites, infections or periampullary diverticula), benign or malignant tumors. Mural thickening and attenuation pattern of contrast medium may be of help for differentiating normal from pathological papilla[65]. CT spatial resolution is often inadequate to define the local tumor invasion into the surrounding structures[66]. As a final consideration, CT is however always necessary for staging any malignant disease, as it can identify distant metastatic involvement like regional lymph-nodes, liver, peritoneum, lung and bone. CT virtual endoscopy is a new non-invasive diagnostic tool, which still has to be more extensively evaluated and developed[67].

Endoscopy is particularly helpful in establishing the diagnosis. In about two thirds of cases, ampullary and duodenal neoplasm are visible endoscopically as exophytic or ulcerated masses[21]. Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP), is useful for distinguishing true ampullary malignancies from pancreatic and bile duct tumors thanks to the visualization of the site and the extent of the stenosis[68]. Moreover ERCP allows the operator to perform a biopsy from the papilla and ampullary segment of the common bile duct (CBD) or pancreatic duct. In addition placement of a stent for biliary decompression if necessary is technically feasible. However it must be underlined that a biliary stent should be placed only once diagnosis is achieved, since it can interfere with all the radiologic exams (CT, RM, EUS) and create inflammatory reaction in the biliary duct[61].

Endoscopic signs suggesting the presence of carcinoma are ulceration, erosion, haemorrhage, necrosis and firm or friable consistency. In particular a malignancy is strongly suspected if the mass is ulcerated or over 3 cm in size[69,70]. Tumors contained within the ampulla appear as prominent submucosal bulge[71].

Biopsy of the lesion is mandatory, but since false negative rates of endoscopic biopsy can be as high as 50%, a negative result is insufficient to rule out the presence of a malignancy in an ampullary lesion[72,73]. Reported accuracy of biopsies range from 47% to 95%[74,75].

The overall accuracy rate with ERCP has been reported around 88% for the diagnosis and origin of the tumors in the ampullary region; attempts to enhance the accuracy include acquisition of tissue at least 48 h following sphincterotomy, multiple biopsies, the use of PCR (polymerase chain reaction) or immunohistochemical staining to detect p53 or k-ras gene mutations, but none of these methods are routinely used in clinical practice.

However, technical factors limit the ability to perform a satisfactory ERCP in 22% of patients with suspected ampullary carcinoma[68,76]. ERCP presents several limitations: intra-ampullary carcinomas are covered by intact duodenal mucosa and in 25%-50% of cases biopsy material discloses only adenoma when deeper portions of the lesion contain invasive carcinoma. In addition peri-vaterian diverticula (present in up to 20% of cases in endoscopic and autoptic series[77,78]) can obstacle technical feasibility of the endoscopic manoeuvres. Snare biopsies yield more tissue than forceps and therefore are more sensitive in detecting adenocarcinoma[74].

MRCP is a non-invasive diagnostic tool with a well-established value in the evaluation of pancreatobiliary lesions[79,80] However, its accuracy for detection of ampullary tumors is limited by the small size of the ampulla and by the scarce amount of fluid due to tapering of the ducts: this area has been defined as a “blind spot” for MRI[81]. Compared to EUS, MRI can detect ampullary tumors in 3/4 of cases[82].

EUS, allowing close contact of the transducer to the duodenal wall, not only has an optimal sensitivity in lesion detection, approaching 100%, but also provides a precise definition of invasion of the surrounding tissue, with 63%-84% accuracy in T staging[5,60,64,74,82-85].

Nowadays EUS should be performed in all patients with suspected ampullary tumors, since the evaluation of the T code is of paramount importance for the choice of treatment (ampullectomy vs pancreaticoduodenectomy). In this setting EUS can give important data regarding the depth of wall infiltration.

More recently, intraductal ultrasounds (IDUS), by inserting the echo probe inside the ducts, has further increased diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic imaging modalities[74,84].

However, this technique still has a limited availability in daily clinical practice.

Although advanced endoscopic techniques can help to differentiate ampullary adenomas from carcinomas, it might be difficult to completely rule out a carcinoma without complete resection of the lesion. Endoscopic ampullectomy can therefore be also a useful diagnostic tool in case of a suspicious mass without definite malignant features.

Once the diagnosis of ampullary carcinoma is made, provided that resectability is judged as feasible, pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), either with conventional or pylorus-preserving approach (PPPD), is considered the standard of care. A recent meta-analysis of six randomized trials showed no significant differences in mortality and morbidity between the two procedures, although operating time and intraoperative blood loss are reduced in the PPPD group[86].

Resectability rate is high for ampullary neoplasm and, in current series, the rate of potentially curative resection has increased up to 90%[18,28,51,87-89] Long-term survival is possible after pancreaticoduodenectomy, even for patients with lymph node metastases or invasion beyond the duodenal wall (T3).

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is a demanding procedure, with significant morbidity. In recent reports from high-volume centers, perioperative mortality rate is consistently reported in less than 5% of cases (Table 2). However, significant complications occur in 20%-40% of patients, including pancreatic fistula, pneumonia, intra-abdominal infection, anastomotic leak and delayed gastric emptying[50,51,87,90-93]. In particular, compared to patients with pancreatic cancer, the incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula is higher (28% vs 6%), perhaps since a normal, soft pancreatic tissue is less likely to hold a suture[94].

After curative resection, nodal status is one of the strongest predictors of survival: indeed, in one series pancreaticoduodenectomy in node-negative patients resulted curative in 80% of cases, while only 25% of patients with positive nodes were alive at 5 years[91]. Interestingly, in the same report no disease- related death occurred more than 3 years after the procedure, consistently with other data that indicate a median time to relapse of 11-13 mo[95,96]. However, cases of tumor recurrence beyond 5 years after resection have been reported[52], underlying the importance of performing accurate and long-lasting postoperative surveillance.

In contrast to pancreatic cancers, in case of ampullary cancer a “lymphatic pathway” has been identified, extending from posterior pancreatico-duodenal nodes around the mesenteric artery up to para-aortic lymph nodes[50,97]. As a result, even in advanced stages, compared to pancreatic carcinoma, nodal involvement is closer to the primary tumor and generally involves a single group of lymph nodes. However the clearance of the abovementioned nodal stations is of paramount importance during pancreaticoduodenectomy for ampullary carcinoma.

Compared to standard PD, ampullectomy is a less invasive procedure. Due to technical improvements in endoscopic techniques over the last decade, local resection of the ampulla can be performed endoscopically and this approach reduces to minimum the procedural trauma. A general main limitation of ampullectomy is the lack of lymphadenectomy.

Endoscopic ampullectomy is therefore a widely accepted therapy for benign ampullary lesions, provided that histological examination shows no signs of invasive carcinoma and that resection margins are negative. Its success rate ranges from 74% to 84%[98-103]. The incidence of periprocedural complications is reported from 10% to 21%. They include bleeding, papillary stenosis, cholangitis and acute pancreatitis, which is the most frequent complication, ranging from 8% to 19%[98,100-103]; this adverse event appears to be reduced by placing a pancreatic duct stent during the procedure[101,104,105].

One of the largest case series of benign adenomas has recently been reported by the retrospective analysis of Onkendi et al[106]; 180 patients were treated either with endoscopic (n = 130) or surgical resection (n = 50, including local resection and PD). Endoscopic treatment was associated with fewer complications compared to surgery (29% vs 58%, P < 0.001). However, the recurrence rate was five-fold higher in this group (P = 0.006), and seven cases of recurrence presented with malignant behavior. Endoscopic ampullectomy was associated with an acceptable recurrence rate when complete resection could be achieved in one session, tumor size was < 3.6 cm and limited intraductal extension (< 5 mm) was found at EUS.

If histological examination shows severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ, endoscopic ampullectomy can still be performed[50,107-109]; however the procedure should be converted to standard PD if an invasive cancer is detected. In this regard, endoscopic ampullectomy can be considered part of the diagnostic workup, when the lesion is small and no signs of malignancy are clearly evident at preoperative evaluation.

The role of surgical local excision is nowadays less defined. First of all it should be remarked that, due to technical improvements in endoscopy over the time, there has been a progressive shift from surgical to endoscopic ampullectomy in reported case series. Therefore, literature about ampullectomy is quite inhomogeneous. Surgical ampullectomy allows to perform lymphadenectomy and has a mortality rate < 1%. However, lymphadenectomy in these cases does not include lymph node stations along the superior mesenteric artery. Apart from the same complications of endoscopic treatment, it carries the risk of duodenal dehiscence, intra-abdominal collections, wound infections and cardiopulmonary complications related to general anesthesia[50,110]. In a paper comparing adverse events after surgical and endoscopic ampullectomy, morbidity was significantly higher in the surgical arm (42% vs 18%, P = 0.006)[111]. On the other hand, in the paper by Onkendi, surgical ampullectomy, compared to endoscopic techniques, did not offer a significant benefit in preventing recurrences after adenoma resection[106]. Some operators however remark the fact that, compared to endoscopic approach, the feasibility of surgical ampullectomy is higher, particularly in case of duodenal diverticula; the success rate of surgical excision is reported to be > 95%[110]. However, in our opinion the morbidity advantage of surgical ampullectomy with lymph node dissection compared to standard PD is limited, provided that surgery is performed in a high-volume center.

Some Authors have proposed that low risk carcinomas can be treated with ampullectomy[112]; this strategy is based on assumption that absence of muscularis propria involvement is associated with a low risk of lymphatic involvement. Klein et al[113] have retrospectively compared the results of 9 patients with ampullary carcinoma treated with surgical local excision (either because of unexpected malignancy or high surgical risk) with other 26 cases who underwent PD in the same period. They found reduced perioperative morbidity and mortality, no cases of local recurrence and comparable long term survival. Based upon these results, the Authors claimed that patients at low risk (defined as pT1, G1-2) could be routinely treated with local excision. However one of the patients who underwent PD was found to have positive nodes despite a pT1-G2 tumor, which would have remained undetected if a local resection had been carried out.

Accordingly, Beger et al[50] proposed surgical ampullectomy with local lymph node dissection in pT1, N0, G1-2 tumors. Among 10 patients who underwent this procedure for ampullary carcinoma, 6 had a R1 resection, but did not undergo PD because of major comorbidities and none of them survived at 3 years. Among the other 4 patients, 1 died at 6 years, but without tumor recurrence.

In our opinion, this approach - limited resection in low-risk patients - deserves some considerations. First of all, there are data suggesting that nodal involvement is not exceptional in T1 tumors[114]. As in recently presented data by Hornick et al[16] 45% of pathologically confirmed T1 tumors had nodal metastases; furthermore, 50% of T1 ampullary cancers have been found to have microscopic lymphatic invasion[52]. Moreover, complication rates with current surgical and anesthesiological techniques are much lower than previously reported and the benefit of a less invasive procedure appears questionable in a population with a standard surgical risk. In the series reported by Roggin et al[115], 7 out of 8 patients treated with ampullectomy experienced recurrence of disease (mostly at a loco regional level) and had a substantially higher mortality compared with the PD group. The data supporting the use of ampullectomy in ampullary cancer, conversely, are scarce and based on a limited number of patients.

Due to these considerations, patients presenting with an invasive ampullary carcinoma should be routinely treated with PD, even for “low risk” cases. Ampullectomy for malignant lesions should be reserved only for patients with a high surgical risk; if complete resection cannot be achieved conventional PD should be strongly considered because of the high recurrence rate.

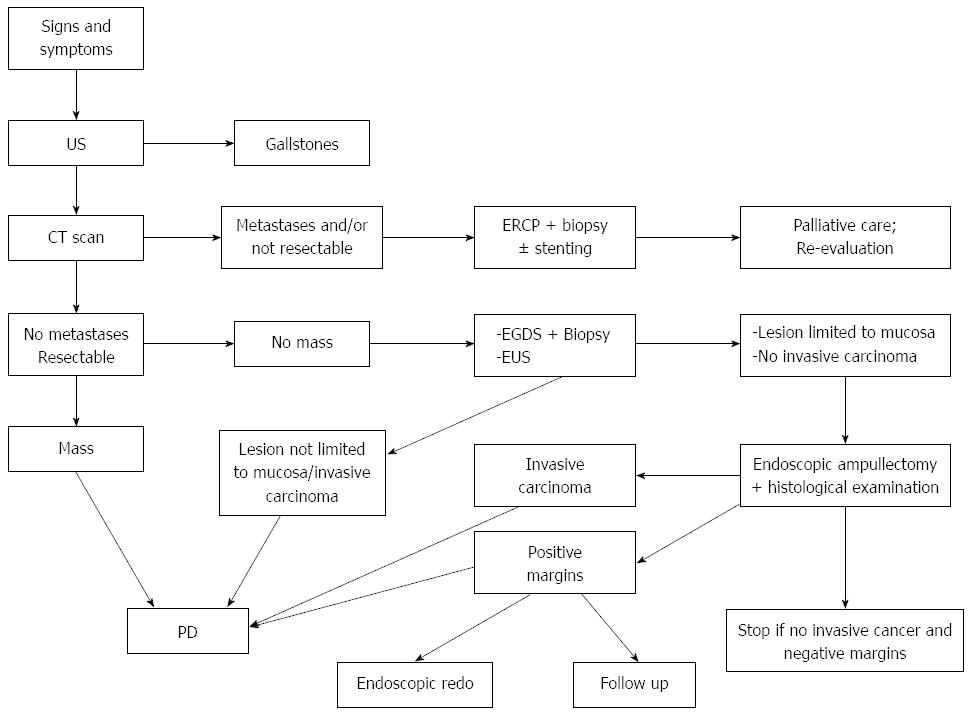

Our approach is synthesized in Figure 3: if preoperatively the lesion appears as a mass at CT scan, then PD is advisable. In case of a small lesion, if biopsies exclude the presence of an infiltrating neoplasm and EUS shows that the lesion is confined within the mucosa, endoscopic ampullectomy should be performed. If the subsequent histological exam shows the presence of infiltrating cancer, then the intervention should be converted to PD. In case of positive resection margins, with no evidence of infiltrating cancer, the management is more controversial: various options are available, including endoscopic second look, close endoscopic follow-up or PD. Age, comorbidities and patient’s preferences also should be taken into account in order to select the best approach in each case; in most situations, our default strategy is to perform endoscopic redo or a close follow up, in order to avoid PD for a benign pathology.

Another matter of debate regarding surgical treatment of ampullary cancer is the opportunity to perform preoperative biliary drainage. This procedure appears to be reasonable if the surgical operation has to be delayed and there are high bilirubin levels (> 15 mg/dL). This policy seems to be suggested by a reduced incidence of wound infection in patients who underwent preoperative biliary drainage, with no differences in other outcomes[116]. On the other hand, biliary drainage can induce inflammation of the biliary tract and surrounding tissues, making assessment of resection margins more difficult.

Laser ablation and photodynamic therapy (which consists of intravenous administration of a photosensitizing agent, that is mainly retained in malignant tissue, followed by endoscopic irradiation with light) is a minimally invasive technique that might be applied for ampullary lesion treatment. However, given its limited efficacy, lack of histological data and risk of tumor recurrence, it is currently regarded only as a palliative procedure[117,118]. In a small series, photodynamic therapy appeared safe and useful as adjuvant treatment for biliary tract cancer (including one case of ampullary carcinoma)[119], but data from larger studies are lacking.

Despite good resectability rates and relatively better prognosis compared to other periampullary malignancies, recurrence of the disease still represents a substantial issue, particularly in patients with nodal involvement[91,95,96].

Currently, no clear indications exist regarding the role of adjuvant therapy after successful pancreatic resection. Some data have suggested a potential benefit of adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil, particularly in node-positive patients[120,121], but randomized trials failed to confirm such a survival advantage[122,123].

Also the role of adjuvant chemotherapy alone is not clearly established. A recent randomized trial assigned 428 patients with a periampullary cancer (297 with papillary tumors) either to observation or adjuvant chemotherapy, with either gemcitabine or fluorouracil. Even if the difference was not significant at univariate analysis, after adjusting for some confounder factors, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a significant survival benefit[124].

The role of neo-adjuvant therapy for advanced ampullary cancer is not defined, as most studies have included ampullary neoplasms with other malignancies due to their rare occurrence. Most probably, chemotherapy should be tailored according to specific histological subtype, i.e. pancreatobiliary vs intestinal.

However, guidelines from both the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)[125] and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO)[126] do not provide any recommendation about treatment of ampullary cancer.

Similarly, the optimal post-treatment surveillance is poorly defined. Most clinicians perform follow up with history, clinical examination and serum tumor markers (CEA and CA 19-9) every six months for five years and annually thereafter. The use of abdomen CT scan is less defined in this setting.

Overall survival rate at 5 years is widely variable between different reports, ranging from 32% to 67.7%. Table 2 reports several studies. Only recent studies (publication from 1995) were considered in order to avoid diagnostic, histological or surgical biases. In fact more recent series report a better prognosis due to both diagnostic and surgical improvement[39].

In patients who undergo a potentially curative resection, the presence of nodal metastases, poorly differentiated histology, and tumor invasion into the pancreas are associated with a less favourable outcome. The great majority of data show positive nodes as a predictor of poor prognosis with worse survival or recurrence. In 17 out of 25 studies nodal metastases are demonstrated as an independent poor prognostic factor. In patients with metastatic lymph nodes 5-year survival varies from 21% to 50.8%, compared to 43%-63.5% in nodes negative patients (Table 2)[50,51,127-129].

In consideration of such a strong evidence, a few recent works better investigated lymph nodes role in ampulla tumors using lymph nodes ratio - a recently established prognostic factor in several gastrointestinal malignancies, that means ratio between metastatic and resected/examined lymph nodes (LNR) - and number of positive lymph nodes in relation to prognosis. In these studies the number of affected lymph nodes resulted as an independent poor prognostic factor; lymph nodes ratio results as a predictor of poor prognosis[19,130,131], but only in one study did it retain significance at multivariate analysis[19]. The issue of how many lymph nodes should be harvested during PD for ampullary cancer was addressed by Partelli et al[132] who found that removal of > 12 nodes was associated with an improved prognosis both in pN0 and pN1 patients, providing evidence that an adequate lymph node dissection plays an important role in better staging (pN0 cohort) and in more effective resection (in pN1 patients).

Poor differentiation (G3) was also found as a predictor of adverse prognosis in 12 studies but as an independent factor in only one study. An advanced T classification and AJCC stage - also poor prognosis predictors - were found as independent factors in 30% and 50% of considered studies, respectively. Pancreatic invasion and tumor size also result as predictors of poor prognosis but they can be easily correlated to T classification and AJCC stage by definition.

Although not included in the TNM classification, pancreatobiliary subtype, perineural, lymphatic and vessels invasion, macroscopic ulceration are other adverse prognostic factors[20,25]. As shown in Table 2 several studies proved that perineural, lymphatic and vessel invasion are predictors of poor prognosis, often also at multivariate analysis. The same consideration is true for pancreatobiliary compared to intestinal subtype, but there are very few studies that deal with this issue because this histological sub classification is relatively recent. In order to better investigate the importance of this predictor Westgaard et al[25] analysed 114 resected periampullary adenocarcinomas (including neoplasm originated from ampullary, duodenal, biliary and ductal pancreatic epithelium), dividing them into pancreatobiliary or intestinal type of differentiation, and compared their survival with a historical control group. The authors found that at multivariable analysis histologic subtype of differentiation was an independent predictor of survival, while tumor origin was not. Pancreatobiliary type was found to have a worse prognosis in the whole periampullary group and also in the subgroup of ampullary carcinomas, with a 5 years survival rate around 25%[33,54] and a more than 3-fold increase in mortality risk compared to intestinal type[25].

Tumor involvement of resection margins has also consistently been demonstrated to be an adverse prognostic factor in comparison with negative margin resections (median survival 11.3 mo vs 59.5 mo, respectively)[28] and warrants the use of the residual tumor classification on specimen assessment (R0: grossly and microscopically negative margins, R1: grossly negative but microscopically positive margins and R2: grossly and microscopically positive margins)[133].

A recent study has also shown the importance of tumor budding. Tumor budding is an already established predictor of survival in colorectal, oesophageal and anal squamous cell carcinomas. It is defined as presence of isolated or small clusters of tumor cells that detached from the neoplastic epithelium and migrate a short distance into the neoplastic stroma. High-budding resulted to be a strong independent predictor of survival also in ampullary cancers (5-years survival of 24% compared to 68% for low-budding tumors)[134].

Moreover in a recent preliminary study Park et al[135] investigated the role of angiogenesis on survival in node negative ampullary tumors. Using a specific staining (Chalkley assay) for angiogenesis quantification they found that increased angiogenesis is associated with disease recurrence in patients with node negative tumors. Investigation of the mechanism of angiogenesis in cancer of the ampulla of Vater may provide further prognostic information and help to rationalize therapy.

It must however be remarked that currently, despite the large number of studies regarding prognosis of these neoplasm, our understanding of the argument is limited by the small cohorts of patients analyzed and by the presence of a lot of confounders, such as stage, pathological subtypes, surgical resection, co-morbidities or adjuvant treatments.

P- Reviewer: Ivanov KD, Klinge U, Pavlidis TE S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER), SEER stat database: Incidence-SEER regs limited use. Available from: http://www.seer.cancer.gov. |

| 2. | Albores-Saavedra J, Henson DE, Klimstra DS. Tumors of the Gallbladder, Extrahepatic Bile Ducts, and Ampulla of Vater - Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Washington, D.C. : Armed Forces Institute of Pathology 1998; . |

| 3. | Kimura W, Ohtsubo K. Incidence, sites of origin, and immunohistochemical and histochemical characteristics of atypical epithelium and minute carcinoma of the papilla of Vater. Cancer. 1988;61:1394-1402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cattell RB, Pyrtek LJ. Premalignant lesions of the ampulla of Vater. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1950;90:21-30, illust. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Chen WX, Xie QG, Zhang WF, Zhang X, Hu TT, Xu P, Gu ZY. Multiple imaging techniques in the diagnosis of ampullary carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:649-653. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Miyakawa S, Ishihara S, Takada T, Miyazaki M, Tsukada K, Nagino M, Kondo S, Furuse J, Saito H, Tsuyuguchi T. Flowcharts for the management of biliary tract and ampullary carcinomas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:7-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pancreatric Section, British Society of Gastroenterology; Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland; Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland; Royal College of Pathologists; Special Interest Group for Gastro-Intestinal Radiology. Guidelines for the management of patients with pancreatic cancer periampullary and ampullary carcinomas. Gut. 2005;54 Suppl 5:v1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Binmoeller KF, Boaventura S, Ramsperger K, Soehendra N. Endoscopic snare excision of benign adenomas of the papilla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:127-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Albores-Saavedra J, Schwartz AM, Batich K, Henson DE. Cancers of the ampulla of vater: demographics, morphology, and survival based on 5,625 cases from the SEER program. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:598-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Matsumoto T, Iida M, Nakamura S, Hizawa K, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M, Fujishima M. Natural history of ampullary adenoma in familial adenomatous polyposis: reconfirmation of benign nature during extended surveillance. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1557-1562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bakkevold KE, Arnesjø B, Kambestad B. Carcinoma of the pancreas and papilla of Vater--assessment of resectability and factors influencing resectability in stage I carcinomas. A prospective multicentre trial in 472 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1992;18:494-507. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Walsh DB, Eckhauser FE, Cronenwett JL, Turcotte JG, Lindenauer SM. Adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Diagnosis and treatment. Ann Surg. 1982;195:152-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Neoptolemos JP, Talbot IC, Carr-Locke DL, Shaw DE, Cockleburgh R, Hall AW, Fossard DP. Treatment and outcome in 52 consecutive cases of ampullary carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1987;74:957-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Baczako K, Büchler M, Beger HG, Kirkpatrick CJ, Haferkamp O. Morphogenesis and possible precursor lesions of invasive carcinoma of the papilla of Vater: epithelial dysplasia and adenoma. Hum Pathol. 1985;16:305-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Yokoyama N, Shirai Y, Wakai T, Nagakura S, Akazawa K, Hatakeyama K. Jaundice at presentation heralds advanced disease and poor prognosis in patients with ampullary carcinoma. World J Surg. 2005;29:519-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hornick JR, Johnston FM, Simon PO, Younkin M, Chamberlin M, Mitchem JB, Azar RR, Linehan DC, Strasberg SM, Edmundowicz SA. A single-institution review of 157 patients presenting with benign and malignant tumors of the ampulla of Vater: management and outcomes. Surgery. 2011;150:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kamisawa T, Tu Y, Egawa N, Nakajima H, Horiguchi S, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A. Clinicopathologic features of ampullary carcinoma without jaundice. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:162-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bettschart V, Rahman MQ, Engelken FJ, Madhavan KK, Parks RW, Garden OJ. Presentation, treatment and outcome in patients with ampullary tumours. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1600-1607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Falconi M, Crippa S, Domínguez I, Barugola G, Capelli P, Marcucci S, Beghelli S, Scarpa A, Bassi C, Pederzoli P. Prognostic relevance of lymph node ratio and number of resected nodes after curative resection of ampulla of Vater carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3178-3186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lazaryan A, Kalmadi S, Almhanna K, Pelley R, Kim R. Predictors of clinical outcomes of resected ampullary adenocarcinoma: a single-institution experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37:791-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ponchon T, Berger F, Chavaillon A, Bory R, Lambert R. Contribution of endoscopy to diagnosis and treatment of tumors of the ampulla of Vater. Cancer. 1989;64:161-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Petrou A, Bramis K, Williams T, Papalambros A, Mantonakis E, Felekouras E. Acute recurrent pancreatitis: a possible clinical manifestation of ampullary cancer. JOP. 2011;12:593-597. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Tsukada K, Takada T, Miyazaki M, Miyakawa S, Nagino M, Kondo S, Furuse J, Saito H, Tsuyuguchi T, Kimura F. Diagnosis of biliary tract and ampullary carcinomas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:31-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chen YF, Mai CR, Tie ZJ, Feng ZT, Zhang J, Lu XH, Lu GJ, Xue YH, Pan GZ. The diagnostic significance of carbohydrate antigen CA 19-9 in serum and pancreatic juice in pancreatic carcinoma. Chin Med J (Engl). 1989;102:333-337. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Westgaard A, Tafjord S, Farstad IN, Cvancarova M, Eide TJ, Mathisen O, Clausen OP, Gladhaug IP. Pancreatobiliary versus intestinal histologic type of differentiation is an independent prognostic factor in resected periampullary adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Akwari OE, van Heerden JA, Adson MA, Baggenstoss AH. Radical pancreatoduodenectomy for cancer of the papilla of Vater. Arch Surg. 1977;112:451-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wise L, Pizzimbono C, Dehner LP. Periampullary cancer. A clinicopathologic study of sixty-two patients. Am J Surg. 1976;131:141-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Howe JR, Klimstra DS, Moccia RD, Conlon KC, Brennan MF. Factors predictive of survival in ampullary carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1998;228:87-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Michelassi F, Erroi F, Dawson PJ, Pietrabissa A, Noda S, Handcock M, Block GE. Experience with 647 consecutive tumors of the duodenum, ampulla, head of the pancreas, and distal common bile duct. Ann Surg. 1989;210:544-554; discussion 554-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Cubilla AL, Fitzgerald PJ. Surgical pathology aspects of cancer of the ampulla-head-of-pancreas region. Monogr Pathol. 1980;21:67-81. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Tasaka K. Carcinoma in the region of the duodenal papilla. A histopathologic study (author’s transl). Fukuoka Igaku Zasshi. 1977;68:20-44. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Kayahara M, Nagakawa T, Ohta T, Kitagawa H, Miyazaki I. Surgical strategy for carcinoma of the papilla of Vater on the basis of lymphatic spread and mode of recurrence. Surgery. 1997;121:611-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kimura W, Futakawa N, Yamagata S, Wada Y, Kuroda A, Muto T, Esaki Y. Different clinicopathologic findings in two histologic types of carcinoma of papilla of Vater. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1994;85:161-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Kim WS, Choi DW, Choi SH, Heo JS, You DD, Lee HG. Clinical significance of pathologic subtype in curatively resected ampulla of vater cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:266-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Chareton B, Coiffic J, Landen S, Bardaxoglou E, Campion JP, Launois B. Diagnosis and therapy for ampullary tumors: 63 cases. World J Surg. 1996;20:707-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kimura W, Futakawa N, Zhao B. Neoplastic diseases of the papilla of Vater. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:223-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Sessa F, Furlan D, Zampatti C, Carnevali I, Franzi F, Capella C. Prognostic factors for ampullary adenocarcinomas: tumor stage, tumor histology, tumor location, immunohistochemistry and microsatellite instability. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:649-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Chu PG, Schwarz RE, Lau SK, Yen Y, Weiss LM. Immunohistochemical staining in the diagnosis of pancreatobiliary and ampulla of Vater adenocarcinoma: application of CDX2, CK17, MUC1, and MUC2. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:359-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Albores-Saavedra J, Henson DE, Klimstra DS. Malignant epithelial tumors of the ampulla. Tumors of the gallbladder, extrahepatic bile ducts, and ampulla of Vater. Washington, D.C. : Armed Forces Institute of Pathology 2000; 259-316. |

| 40. | Albores-Saavedra J, Menck HR, Scoazec JC, Sohendra N, Wittekind C, Sriram PVJ, Sripa B. Carcinoma of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC Press 2000; 206-213. |

| 41. | Bergan A, Gladhaug IP, Schjolberg A, Bergan AB, Clausen OP. p53 accumulation confers prognostic information in resectable adenocarcinomas with ductal but not with intestinal differentiation in the pancreatic head. Int J Oncol. 2000;17:921-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Zhou H, Schaefer N, Wolff M, Fischer HP. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: comparative histologic/immunohistochemical classification and follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:875-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Albores-Saavedra J, Hruban RH, Klimstra DS, Zamboni G. Invasive adenocarcinoma of the ampullary region. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon (France): IARC Press 2010; 87-91. |

| 44. | Kshirsagar AY, Nangare NR, Vekariya MA, Gupta V, Pednekar AS, Wader JV, Mahna A. Primary adenosquamous carcinoma of ampulla of Vater-A rare case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:393-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Hoang MP, Murakata LA, Katabi N, Henson DE, Albores-Saavedra J. Invasive papillary carcinomas of the extrahepatic bile ducts: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:1251-1258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Kloppel G, Arnold R, Capella D, klimstra J, Albores-Saavedra J, Solcia E, Rindi G, Komminoth P. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the ampullary region. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon (France): IARC Press 2010; 92-94. |

| 47. | Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer 2010; . |

| 48. | Shirai Y, Tsukada K, Ohtani T, Koyama S, Muto T, Watanabe H, Hatakeyama K. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: histopathologic analysis of tumor spread in Whipple pancreatoduodenectomy specimens. World J Surg. 1995;19:102-106; discussion 106-107. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Warren KW, Choe DS, Plaza J, Relihan M. Results of radical resection for periampullary cancer. Ann Surg. 1975;181:534-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Beger HG, Treitschke F, Gansauge F, Harada N, Hiki N, Mattfeldt T. Tumor of the ampulla of Vater: experience with local or radical resection in 171 consecutively treated patients. Arch Surg. 1999;134:526-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Talamini MA, Moesinger RC, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Hruban RH, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL. Adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. A 28-year experience. Ann Surg. 1997;225:590-599; discussion 599-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Monson JR, Donohue JH, McEntee GP, McIlrath DC, van Heerden JA, Shorter RG, Nagorney DM, Ilstrup DM. Radical resection for carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Arch Surg. 1991;126:353-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Yoon SM, Kim MH, Kim MJ, Jang SJ, Lee TY, Kwon S, Oh HC, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK. Focal early stage cancer in ampullary adenoma: surgery or endoscopic papillectomy? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:701-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Carter JT, Grenert JP, Rubenstein L, Stewart L, Way LW. Neuroendocrine tumors of the ampulla of Vater: biological behavior and surgical management. Arch Surg. 2009;144:527-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Key C, Meisner A. Cancers of the Liver and Biliary Tract. SEER Survival Monograph: Cancer Survival Among Adults: U.S. SEER Program, 1988-2001, Patient and Tumor Characteristics. Ries LAG: National Cancer Institute, SEER Program 2007; . |

| 56. | Greene FL. TNM staging for malignancies of the digestive tract: 2003 changes and beyond. Semin Surg Oncol. 2003;21:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Willett CG, Warshaw AL, Convery K, Compton CC. Patterns of failure after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ampullary carcinoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;176:33-38. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Lim JH, Lee DH, Ko YT, Yoon Y. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: sonographic and CT diagnosis. Abdom Imaging. 1993;18:237-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Qiao QL, Zhao YG, Ye ML, Yang YM, Zhao JX, Huang YT, Wan YL. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: factors influencing long-term survival of 127 patients with resection. World J Surg. 2007;31:137-143; discussion 144-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Skordilis P, Mouzas IA, Dimoulios PD, Alexandrakis G, Moschandrea J, Kouroumalis E. Is endosonography an effective method for detection and local staging of the ampullary carcinoma? A prospective study. BMC Surg. 2002;2:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Chen CH, Tseng LJ, Yang CC, Yeh YH. Preoperative evaluation of periampullary tumors by endoscopic sonography, transabdominal sonography, and computed tomography. J Clin Ultrasound. 2001;29:313-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Komorowski RA, Beggs BK, Geenan JE, Venu RP. Assessment of ampulla of Vater pathology. An endoscopic approach. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:1188-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Midwinter MJ, Beveridge CJ, Wilsdon JB, Bennett MK, Baudouin CJ, Charnley RM. Correlation between spiral computed tomography, endoscopic ultrasonography and findings at operation in pancreatic and ampullary tumours. Br J Surg. 1999;86:189-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Rösch T, Braig C, Gain T, Feuerbach S, Siewert JR, Schusdziarra V, Classen M. Staging of pancreatic and ampullary carcinoma by endoscopic ultrasonography. Comparison with conventional sonography, computed tomography, and angiography. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:188-199. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Kim S, Lee NK, Lee JW, Kim CW, Lee SH, Kim GH, Kang DH. CT evaluation of the bulging papilla with endoscopic correlation. Radiographics. 2007;27:1023-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Rivadeneira DE, Pochapin M, Grobmyer SR, Lieberman MD, Christos PJ, Jacobson I, Daly JM. Comparison of linear array endoscopic ultrasound and helical computed tomography for the staging of periampullary malignancies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:890-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Guo ZJ, Chen YF, Zhang YH, Meng FJ, Lin Q, Cao B, Zi XR, Lu JY, An MH, Wang YJ. CT virtual endoscopy of the ampulla of Vater: preliminary report. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36:514-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Nix GA, Van Overbeeke IC, Wilson JH, ten Kate FJ. ERCP diagnosis of tumors in the region of the head of the pancreas. Analysis of criteria and computer-aided diagnosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:577-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Domagk D, Wessling J, Reimer P, Hertel L, Poremba C, Senninger N, Heinecke A, Domschke W, Menzel J. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, intraductal ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in bile duct strictures: a prospective comparison of imaging diagnostics with histopathological correlation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1684-1689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Blackman E, Nash SV. Diagnosis of duodenal and ampullary epithelial neoplasms by endoscopic biopsy: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Hum Pathol. 1985;16:901-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Huibregtse K, Tytgat GN. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: the endoscopic approach. Endoscopy. 1988;20 Suppl 1:223-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Yamaguchi K, Enjoji M, Kitamura K. Endoscopic biopsy has limited accuracy in diagnosis of ampullary tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:588-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Sauvanet A, Chapuis O, Hammel P, Fléjou JF, Ponsot P, Bernades P, Belghiti J. Are endoscopic procedures able to predict the benignity of ampullary tumors? Am J Surg. 1997;174:355-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Horaguchi J. Diagnosis of ampullary cancer. Dig Surg. 2010;27:115-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Chini P, Draganov PV. Diagnosis and management of ampullary adenoma: The expanding role of endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:241-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Hall TJ, Blackstone MO, Cooper MJ, Hughes RG, Moossa AR. Prospective evaluation of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the diagnosis of periampullary cancers. Ann Surg. 1978;187:313-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Psathakis D, Utschakowski A, Müller G, Broll R, Bruch HP. Clinical significance of duodenal diverticula. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;178:257-260. [PubMed] |

| 78. | Osnes M, Løotveit T, Larsen S, Aune S. Duodenal diverticula and their relationship to age, sex, and biliary calculi. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1981;16:103-107. [PubMed] |

| 79. | Cannon ME, Carpenter SL, Elta GH, Nostrant TT, Kochman ML, Ginsberg GG, Stotland B, Rosato EF, Morris JB, Eckhauser F. EUS compared with CT, magnetic resonance imaging, and angiography and the influence of biliary stenting on staging accuracy of ampullary neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:27-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Materne R, Van Beers BE, Gigot JF, Jamart J, Geubel A, Pringot J, Deprez P. Extrahepatic biliary obstruction: magnetic resonance imaging compared with endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 2000;32:3-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Geier A, Nguyen HN, Gartung C, Matern S. MRCP and ERCP to detect small ampullary carcinoma. Lancet. 2000;356:1607-1608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Manta R, Conigliaro R, Castellani D, Messerotti A, Bertani H, Sabatino G, Vetruccio E, Losi L, Villanacci V, Bassotti G. Linear endoscopic ultrasonography vs magnetic resonance imaging in ampullary tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5592-5597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Mukai H, Yasuda K, Nakajima M. Tumors of the papilla and distal common bile duct. Diagnosis and staging by endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1995;5:763-772. [PubMed] |

| 84. | Heinzow HS, Lenz P, Lallier S, Lenze F, Domagk D, Domschke W, Meister T. Ampulla of Vater tumors: impact of intraductal ultrasound and transpapillary endoscopic biopsies on diagnostic accuracy and therapy. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011;74:509-515. [PubMed] |

| 85. | Kubo H, Chijiiwa Y, Akahoshi K, Hamada S, Matsui N, Nawata H. Pre-operative staging of ampullary tumours by endoscopic ultrasound. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:443-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |