Published online Jun 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i21.6759

Peer-review started: November 9, 2014

First decision: November 26, 2014

Revised: December 10, 2014

Accepted: February 5, 2015

Article in press: February 5, 2015

Published online: June 7, 2015

Processing time: 217 Days and 21.6 Hours

We report the case of a 69-year-old woman with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH) of the liver. She underwent partial hepatectomy under a preoperative diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma; however, histopathological analysis revealed RLH. The liver nodule showed the imaging feature of perinodular enhancement in the arterial dominant phase on contrast-enhanced computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, which could be a useful clue for identifying RLH in the liver. Histologically, the perinodular enhancement was compatible with prominent sinusoidal dilatation surrounding the liver nodule.

Core tip: It is difficult to differentiate between reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH) of the liver and malignant liver tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma and liver metastases. We observed a liver nodule with perinodular enhancement in the arterial dominant phase on contrast-enhanced computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. We consider that this imaging feature could be a useful clue for identifying RLH in the liver. Histological analysis revealed the liver nodule in our patient to be RLH, with prominent sinusoidal dilatation around the nodule. This dilatation is the cause of the perinodular enhancement, which is useful for the accurate diagnosis of RLH.

- Citation: Sonomura T, Anami S, Takeuchi T, Nakai M, Sahara S, Tanihata H, Sakamoto K, Sato M. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: Perinodular enhancement on contrast-enhanced computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(21): 6759-6763

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i21/6759.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i21.6759

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH) is a benign condition of unknown etiology and pathogenesis[1]. It is common in the gastrointestinal tract, orbit, lung, and skin, but rare in the liver, where it is difficult to differentiate from malignant liver tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and liver metastases. The liver nodules with perinodular enhancement on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been reported in some papers in the English-language literature[2-7]. However, few reports have focused on perinodular enhancement in RLH. Histological analysis revealed prominent sinusoidal dilatation surrounding the liver nodule as the cause of the perinodular enhancement. This imaging feature can aid in the accurate diagnosis of RLH.

Informed consent was obtained from the patient. At our institution, approval of the Institutional Review Board is not required for retrospective case reports.

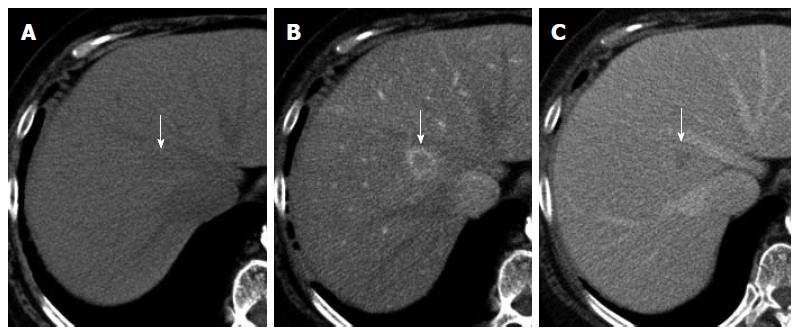

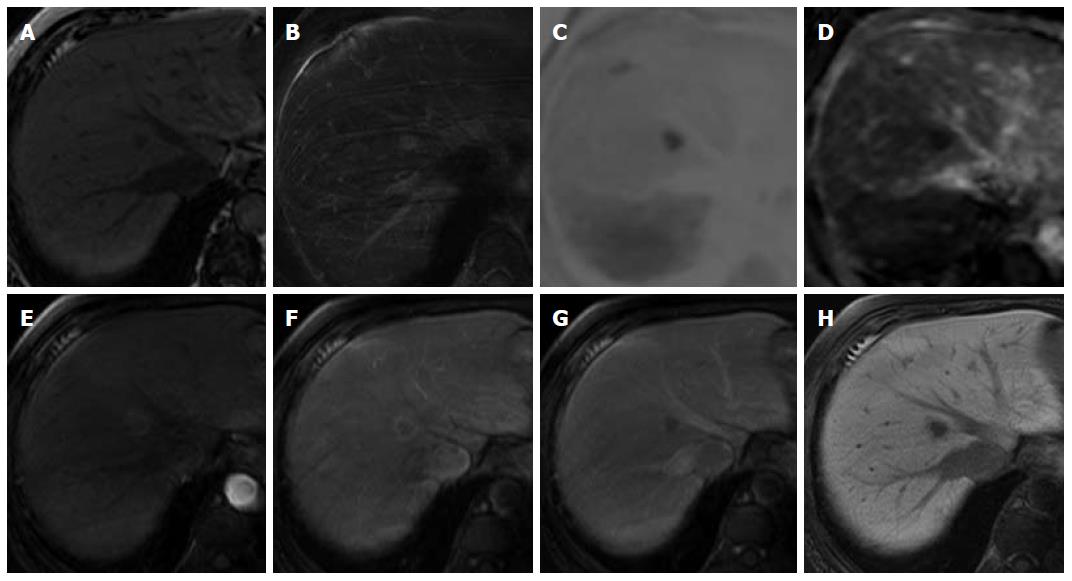

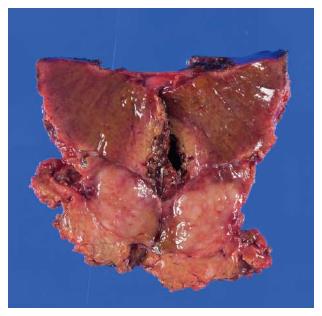

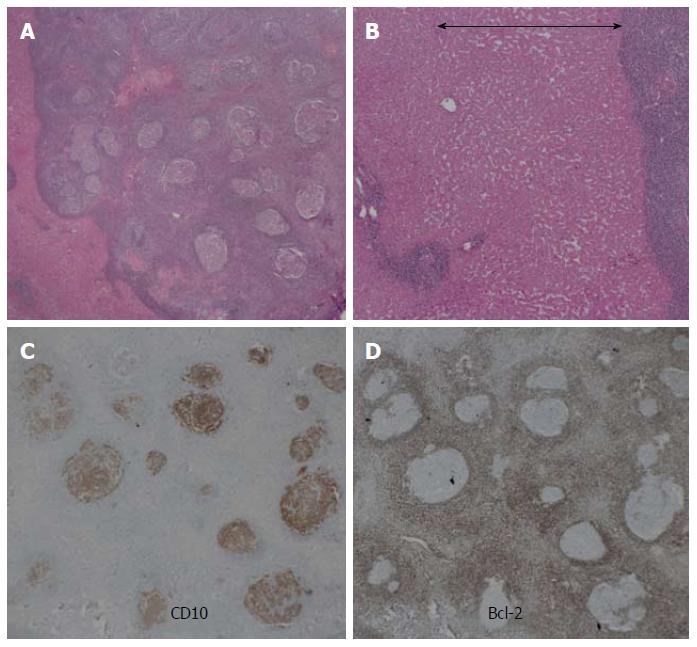

A 69-year-old woman with atrial fibrillation was being followed up at the cardiology department. Abdominal ultrasonography performed to investigate hematuria revealed the incidental finding of a well-defined hypoechoic lesion in Segment 1 of the liver. She had no history of persistent viral infection, autoimmune disease, inflammatory bowel disease or malignant tumors. Her body mass index was 26.7, which means she was overweight, but she had no fatty liver. Blood examination showed that her liver function was normal, and that hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B core antibody, hepatitis C antibody and anti-nuclear antibody were negative. The tumor marker values were α-fetoprotein 4.9 ng/mL, PIVKA-2 31-000 mAU/mL, carcinoembryonic antigen 1.8 ng/mL and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 18.1 U/mL. We considered that the high PIVKA-2 value was due to the warfarin she was taking for atrial fibrillation. Unenhanced CT showed a liver nodule with subtle low attenuation relative to the liver parenchyma. On triple-phase contrast-enhanced CT, the nodule demonstrated perinodular enhancement in the arterial dominant phase, and washout of contrast medium in the equilibrium phase (Figure 1). On unenhanced MRI[8], the nodule showed low signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging and high signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging. The nodule showed high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging (b = 800 m2/s, inverted black-and-white gray scale), and low signal intensity on the apparent diffusion coefficient map. On gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-EOB-DTPA)-enhanced MRI, the nodule showed perinodular enhancement in the arterial dominant phase, washout of contrast medium in the late phase, and low signal intensity in the hepatobiliary phase (Figure 2). Under the preoperative diagnosis of HCC, partial hepatectomy was performed. A section of the resected liver showed a well-circumscribed and yellow-white unencapsulated lesion (15 mm × 10 mm) (Figure 3). However, histopathology confirmed RLH of the liver, characterized by mass infiltration of mature lymphoid cells, forming lymphoid follicles of various sizes, with germinal centers. Prominent sinusoidal dilatation was seen around the nodule. In the perinodular portal tracts, marked lymphoid cell infiltration was observed, but there was no definite evidence of portal venular stenosis or fibrous tissue. Immunohistochemical staining of germinal centers was positive for CD10 and negative for Bcl-2 (Figure 4).

RLH is generally thought to be a benign lesion characterized by hyperplastic lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers[1]. Ota et al[2] and Zen et al[9] reported a reduction in the size of lesions in RLH of the liver; however, the risk of malignant transformation is also reported, namely, the development of malignant lymphoma[10]. Although RLH can be found in various organs, including the gastrointestinal tract, orbit, lung and skin, its occurrence in the liver is rare. It occurs predominantly in middle-aged women (mean age, 54.1 years)[3]. Although the exact etiology remains unknown, associations have been suggested between the development of hepatic RLH and chronic hepatitis[11], autoimmune disease[5,10,12], and malignant tumor[13]. None of these was present in our case.

It is difficult to distinguish between RLH of the liver and malignant liver tumors such as HCC and liver metastases on the basis of the imaging findings[14]. In the present case, the imaging feature of perinodular enhancement was evident in the arterial dominant phase on contrast-enhanced CT and MRI. Perinodular enhancement has previously been described in some papers in the English-language literature[2-7], and may be a useful aid for identifying RLH in the liver. However, few reports have focused on perinodular enhancement in RLH of the liver. Among other tumors of the liver, hypervascular HCCs show enhancement of the perinodular liver parenchyma (corona enhancement) in the late phase images of CT during hepatic arteriography[15], and liver metastases show ring enhancement with central necrosis in three phases on triple-phase contrast-enhanced CT or MRI. Therefore, perinodular enhancement in the arterial dominant phase may enable differentiation of liver RLH from malignant liver tumors. In addition, Osame et al[16] and Yoshida et al[7] observed vessels coursing through a liver lesion (vessel-penetrating sign) on CT, and suggested that this finding may enable malignancy to be excluded.

Histological analysis revealed that the nodule was well-demarcated, with massive infiltration of mature lymphoid cells, forming lymphoid follicles of various sizes with germinal centers, and with prominent sinusoidal dilatation surrounding the nodule. We consider that the sinusoidal dilatation was the cause of the perinodular enhancement in the present case. Yoshida et al[7] considered that perinodular enhancement reflects increased arterial supply to the perinodular hepatic parenchyma caused by portal venular stenosis and/or disappearance, due to marked lymphoid cell infiltration in the perinodular portal tracts[7]. However, there was no definite evidence of portal venular stenosis or fibrous tissue in the perinodular portal tracts in the present case. Immunohistochemical staining of germinal centers was positive for CD10 and negative for Bcl-2. The negative results for Bcl-2 indicate RLH, and exclude follicular lymphoma from our diagnosis[1].

RLH of the liver is not generally diagnosed until after partial hepatectomy. Some reports[2,4] describe needle biopsy for the diagnosis of RLH; however, this procedure has drawbacks that an insufficient sample may be obtained for diagnosis, and that there is a risk of tumor dissemination in the case of a malignant tumor.

In conclusion, RLH should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a small liver nodule that displays perinodular enhancement in the arterial dominant phase on contrast-enhanced CT and MRI.

A 69-year-old woman with atrial fibrillation was being followed up at the cardiology department.

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed the incidental finding of a well-defined hypoechoic lesion in Segment 1 of the liver.

A liver tumor such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and liver metastasis was suspected.

The tumor marker values were α-fetoprotein 4.9 ng/mL, PIVKA-2 31-000 mAU/mL, carcinoembryonic antigen 1.8 ng/mL and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 18.1 U/mL, and we considered that the high PIVKA-2 value was due to the warfarin she was taking for atrial fibrillation.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed perinodular enhancement in the arterial dominant phase, and washout of contrast medium in the late phase.

Under the preoperative diagnosis of HCC, a partial hepatectomy was performed.

Histopathology confirmed RLH of the liver, characterized by massive infiltration of mature lymphoid cells, forming lymphoid follicles of various sizes, with germinal centers.

Some English-language literature has reported that RLH in the liver demonstrated perinodular enhancement on contrast-enhanced CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

RLH is a benign condition of unknown etiology and pathogenesis. It is common in the gastrointestinal tract, orbit, lung, and skin, but rare in the liver, where it is difficult to differentiate from malignant liver tumors such as HCC and liver metastases.

The liver nodule showed the imaging feature of perinodular enhancement in the arterial dominant phase on contrast-enhanced CT and MRI, which could be a useful clue for identifying RLH in the liver.

In a middle-aged female patient, RLH should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a small liver nodule that displays perinodular enhancement in the arterial dominant phase on contrast-enhanced CT and MRI.

P- Reviewer: Baran B, Inoue K, Solinas A S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Yoshikawa K, Konisi M, Kinoshita T, Takahashi S, Gotohda N, Kato Y, Kojima M. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: literature review and 3 case reports. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:1349-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ota H, Isoda N, Sunada F, Kita H, Higashisawa T, Ono K, Sato S, Ido K, Sugano K. A case of hepatic pseudolymphoma observed without surgical intervention. Hepatol Res. 2006;35:296-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Machida T, Takahashi T, Itoh T, Hirayama M, Morita T, Horita S. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5403-5407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Matsumoto N, Ogawa M, Kawabata M, Tohne R, Hiroi Y, Furuta T, Yamamoto T, Gotoh I, Ishiwata H, Ono Y. Pseudolymphoma of the liver: Sonographic findings and review of the literature. J Clin Ultrasound. 2007;35:284-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fukuo Y, Shibuya T, Fukumura Y, Mizui T, Sai JK, Nagahara A, Tsukada A, Matsumoto T, Suyama M, Watanabe S. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver associated with primary biliary cirrhosis. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16:CS81-CS86. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Tuckett J, Hudson M, White S, Scott J. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: a case report and review of imaging characteristics. European J Radiol. 2011;79:e11-14. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yoshida K, Kobayashi S, Matsui O, Gabata T, Sanada J, Koda W, Minami T, Ryu Y, Kozaka K, Kitao A. Hepatic pseudolymphoma: imaging-pathologic correlation with special reference to hemodynamic analysis. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:1277-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kobayashi A, Oda T, Fukunaga K, Sasaki R, Minami M, Ohkohchi N. MR imaging of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1282-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zen Y, Fujii T, Nakanuma Y. Hepatic pseudolymphoma: a clinicopathological study of five cases and review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:244-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sato S, Masuda T, Oikawa H, Satoh T, Suzuki Y, Takikawa Y, Yamazaki K, Suzuki K, Sato S. Primary hepatic lymphoma associated with primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1669-1673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ohtsu T, Sasaki Y, Tanizaki H, Kawano N, Ryu M, Satake M, Hasebe T, Mukai K, Fujikura M, Tamai M. Development of pseudolymphoma of liver following interferon-alpha therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Intern Med. 1994;33:18-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sharifi S, Murphy M, Loda M, Pinkus GS, Khettry U. Nodular lymphoid lesion of the liver: an immune-mediated disorder mimicking low-grade malignant lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:302-308. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Takahashi H, Sawai H, Matsuo Y, Funahashi H, Satoh M, Okada Y, Inagaki H, Takeyama H, Manabe T. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver in a patient with colon cancer: report of two cases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yang CT, Liu KL, Lin MC, Yuan RH. Pseudolymphoma of the liver: Report of a case and review of the literature. Asian J Surg. 2013;S1015-9584(13)00070-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ueda K, Matsui O, Kawamori Y, Nakanuma Y, Kadoya M, Yoshikawa J, Gabata T, Nonomura A, Takashima T. Hypervascular hepatocellular carcinoma: evaluation of hemodynamics with dynamic CT during hepatic arteriography. Radiology. 1998;206:161-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Osame A, Fujimitsu R, Ida M, Majima S, Takeshita M, Yoshimitsu K. Multinodular pseudolymphoma of the liver: computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Jpn J Radiol. 2011;29:524-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |