Published online May 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.6077

Peer-review started: November 30, 2014

First decision: December 26, 2014

Revised: January 26, 2015

Accepted: February 13, 2015

Article in press: February 13, 2015

Published online: May 21, 2015

Processing time: 172 Days and 17.8 Hours

Chylous ascites is the accumulation of a milk-like peritoneal fluid rich in triglycerides and it is an unusual complication following surgical treatment of colorectal cancer. Conservative management is usually sufficient in patients with chylous ascites after surgery. However, we describe a patient with intractable chylous ascites after laparoscopic anterior resection for sigmoid colon cancer who failed initial conservative treatment. This patient was successfully managed by surgery.

Core tip: Chylous ascites is unusual following surgical treatment of colorectal cancer. Postoperative chylous ascites is always difficult to manage, due to the consequences of the primary surgery and the constant loss of lymph. Although conservative management is usually sufficient in patients with chylous ascites after surgery, we describe a patient who experienced intractable chylous ascites after laparoscopic anterior resection for sigmoid colon cancer. This patient was successfully managed by surgery.

- Citation: Ha GW, Lee MR. Surgical repair of intractable chylous ascites following laparoscopic anterior resection. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(19): 6077-6081

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i19/6077.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.6077

Chylous ascites is the accumulation of a milk-like peritoneal fluid rich in triglycerides, due to the presence of lymph in the abdominal cavity. Chylous ascites develops in patients with disruption of the lymphatic system due to traumatic injury or obstruction, which may result from malignancy, liver cirrhosis, infectious etiologies, congenital disorders, and inflammatory diseases[1].

Chylous ascites is unusual following surgical treatment of colorectal cancer. Postoperative chylous ascites is always difficult to manage, due to the consequences of the primary surgery and the constant loss of lymph. Management of chylous ascites may include repeat palliative paracentesis, dietary measures, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) therapy and surgical repair of the fistula[2].

We describe a patient who experienced intractable chylous ascites after laparoscopic anterior resection for sigmoid colon cancer. This patient did not show improvements following primary conservative treatment, including TPN, administration of somatostatin and dietary modification, but was subsequently successfully managed surgically.

In April 2014, a 65-year-old man underwent laparoscopic anterior resection with lymph node dissection up to the level of the inferior mesenteric artery for sigmoid colon adenocarcinoma. The procedure was uneventful. The histopathologic stage was T3N1a. Of the 17 lymph nodes obtained, one was positive for malignancy. The initial postoperative period was unremarkable, except for small amounts of milky, odorless fluid. The volume of drainage decreased and the drain was removed on the fifth postoperative day. The patient was discharged on the seventh postoperative day without any complications.

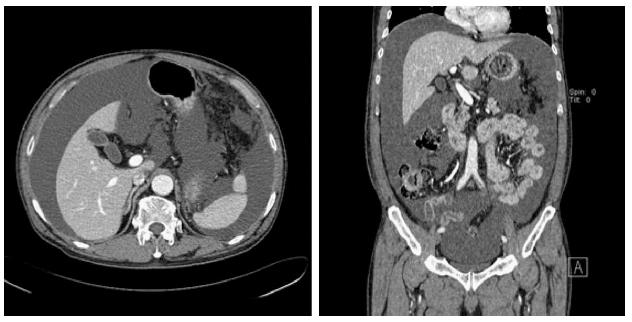

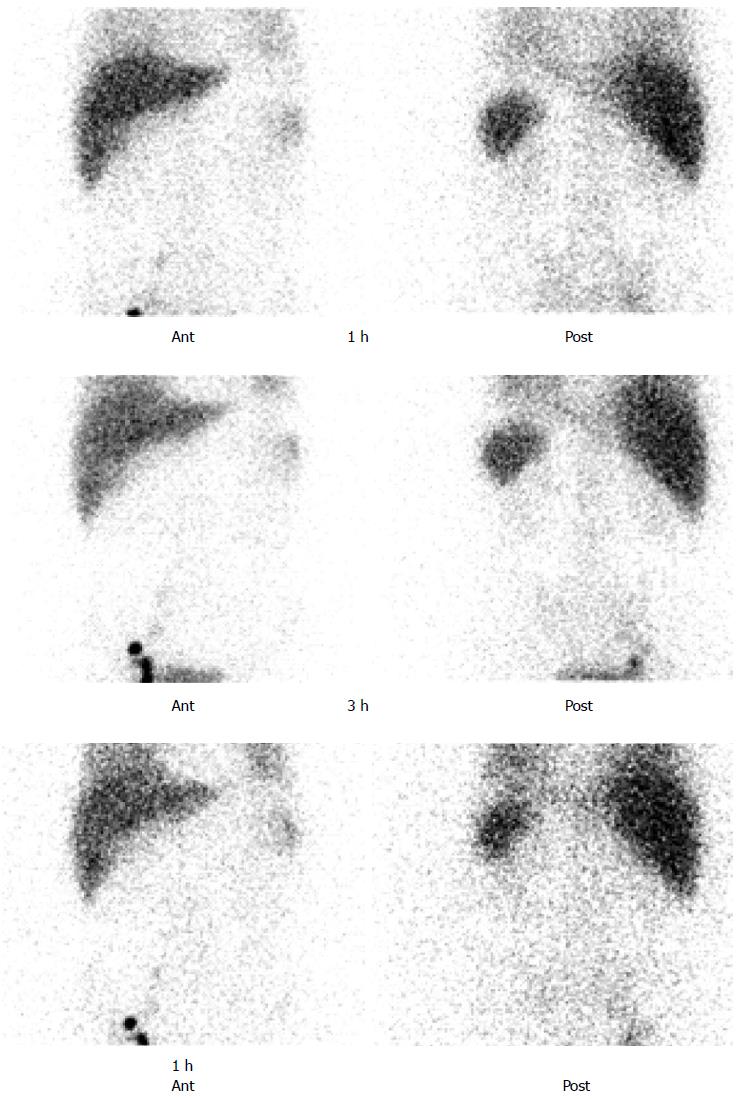

Two weeks later, he complained of increased abdominal girth after discharge from the hospital. On physical examination, he had a moderately distended abdomen with dullness to percussion. Abdominal computed tomography with intravenous (IV) contrast showed a large volume of ascites (Figure 1). The patient was rehospitalized and underwent abdominal percutaneous drainage, which resulted in the removal of 2500 mL of milky white, odorless fluid. Laboratory analysis of the fluid revealed a triglyceride level of 457 mg/dL, albumin 2.3 g/dL, lactic dehydrogenase 112 IU/L, and protein 3.2 g/dL, consistent with chylous ascites. Cytology was negative for malignancy and cultures were negative. All other laboratory tests were nonspecific with a serum albumin level of 2.6 g/dL. The patient was put on a low fat diet and medium chain triglyceride supplementation. After one week, the volume of chylous ascites still drained over 1500 mL per day. At that time, oral feeding was discontinued, and the patient was started on TPN and subcutaneous somatostatin injections, which were continued for four weeks. The volume of drainage had decreased to 300 mL per day, and oral feeding was restarted. This increased the volume of drainage to 1500-3300 mL per day of chylous ascites. Moreover, the poor nutritional status of the patient, with a weight loss of approximately 10 kg, and his desire for a definitive solution led to a plan for surgical treatment. Preoperative lymphoscintigraphy was performed but no specific site of extravasation was identified (Figure 2).

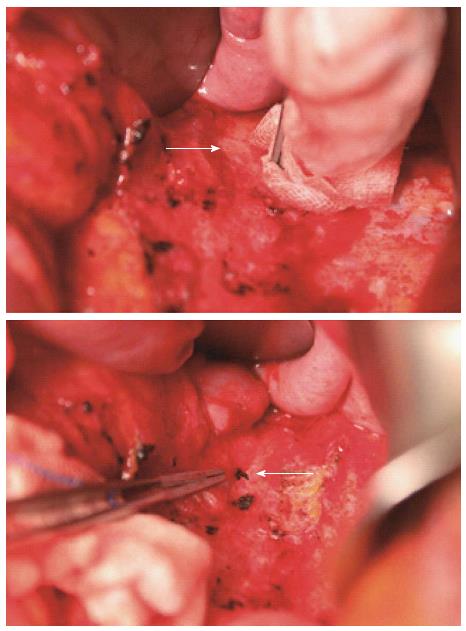

Explorative laparotomy was elected. The patient ingested a high fat food four hours before the operation to facilitate visualization of the lymphatic fistula. A streak of clear chyle was immediately visible. The fistula, considered a branch of left lumbar trunk, was found to stem from a 1 mm hole in one of the lymphatic channels on the left side of the ligated inferior mesenteric artery (Figure 3). The tract was sutured and no additional sites of leakage were found in the abdomen. Ten days after the surgery, the patient was discharged. After three months, there has been no evidence of ascites (Figure 4).

Postoperative chylous ascites is an infrequent condition usually resulting from operative trauma caused by the unrecognized interruption of lymphatic channels[2]. Chylous ascites cannot always be avoided due to the inconsistent anatomy of lymphatic structures. However, meticulous ligation and clipping, or coagulation of lymphatic tissue near the vessel origins, can minimize its occurrence.

The incidence of chylous ascites after laparoscopic anterior resection is not clear. Only two studies have reported cases of this complication, with all patients treated conservatively[3,4]. Conservative management of chylous ascites can include dietary modifications, use of TPN, administration of somatostatin or octreotide, and use of diuretics to reduce lymph formation[5]. Dietary modifications include a high protein, low fat, medium chain triglyceride diet, or interruption of oral feeding. Conservative management is usually successful, making initial, conservative management reasonable in patients with this complication.

Surgical repair may be effective in patients who fail conservative management. However, surgical repair may not be successful and may even cause additional trauma. The timing of surgical repair remains unclear. Surgical and traumatic causes of chylous ascites may be explored early. Congenital and malignant causes may be given longer trials of conservative management. The decision for surgical repair should be tailored to the particular situation of the patient. Patients should be managed conservatively for approximately 6-8 wk before conservative management is judged to have failed[2,5].

If surgical repair of chylous ascites is elected, it is important to have knowledge about the anatomy of lymphatic drainage. For example, in the left colon, lymph from the descending, iliac, and pelvic parts of the colon passes to the intermediate groups of inferior mesenteric glands, with most subsequently passing to the lumbar glands. The main glands of the inferior mesenteric group receive lymph from the intermediate left colic glands and transmit it to the lumbar glands. Lymph then passes through the lumbar lymph trunks to the cisterna chyli. Based on anatomic knowledge, we were easily able to locate the fistula tract in our patient, finding it on the left side of the ligated inferior mesenteric artery. It was considered a branch of the left lumbar lymphatic trunk.

In conclusion, we have described a patient with a lymphatic fistula that appeared through an abdominal drainage after laparoscopic anterior resection. Meticulous ligation and clipping or coagulation of lymphatic tissue near the major vessel origins is important in preventing this complication. Although most patients with chylous ascites may be successfully treated conservatively, those who fail conservative management can undergo surgical repair and it may be performed effectively.

The patient who had undergone laparoscopic anterior resection for sigmoid colon cancer revisited two weeks after discharge from hospital presenting with abdominal distention.

On physical examination, he had a moderately distended abdomen with dullness to percussion.

Intraabdominal abscess caused by delayed anastomotic microperforation.

Laboratory analysis of the ascitic fluid revealed a triglyceride level of 457 mg/dL, albumin 2.3 g/dL, and protein 3.2 g/dL, and all other laboratory tests were nonspecific with a serum albumin level of 2.6 g/dL.

Abdominal computed tomography showed a large volume of ascites.

This patient was successfully managed by surgical repair of the lymphatic fistula.

Surgical repair of intractable chylous ascites after surgery has been reported rarely.

A patient with intractable chylous ascites following surgery can undergo surgical repair and it may be performed effectively.

The authors have described intractable chylous ascites after laparoscopic anterior resection who failed initial conservative treatment. This patient was successfully managed by surgical repair.

P- Reviewer: Marrelli D, Wu WJ S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Cárdenas A, Chopra S. Chylous ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1896-1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Leibovitch I, Mor Y, Golomb J, Ramon J. The diagnosis and management of postoperative chylous ascites. J Urol. 2002;167:449-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bartolini I, Bechi P. Chylous ascites after laparoscopic anterior resection of the rectum. Surgery. 2013;153:875-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Giovannini I, Giuliante F, Chiarla C, Ardito F, Vellone M, Nuzzo G. Non-surgical management of a lymphatic fistula, after laparoscopic colorectal surgery, with total parenteral nutrition, octreotide, and somatostatin. Nutrition. 2005;21:1065-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aalami OO, Allen DB, Organ CH. Chylous ascites: a collective review. Surgery. 2000;128:761-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |