Published online Dec 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17680

Revised: June 17, 2014

Accepted: July 22, 2014

Published online: December 14, 2014

Processing time: 227 Days and 6.8 Hours

Sclerosing cholangitis (SC) is a rarely reported morbidity secondary to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) with bleomycin-iodinated oil (BIO) for liver cavernous hemangioma (LCH). This report retrospectively evaluated the diagnostic and therapeutic course of a patient with LDH who presented obstructive jaundice 6 years after TACE with BIO. Preoperative imaging identified a suspected malignant biliary stricture located at the convergence of the left and right hepatic ducts. Operative exploration demonstrated a full-thickness sclerosis of the hilar bile duct with right hepatic duct stricture and right lobe atrophy. Radical hepatic hilar resection with right-side hemihepatectomy and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was performed because hilar cancer could not be excluded on frozen biopsy. Pathological results showed chronic pyogenic inflammation of the common and right hepatic ducts with SC in the portal area. Secondary SC is a long-term complication that may occur in LCH patients after TACE with BIO and must be differentiated from hilar malignancy. Hepatic duct plasty is a definitive but technically challenging treatment modality for secondary SC.

Core tip: Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) with bleomycin-iodinated oil, a minimally invasive interventional treatment modality, is generally safe for treating liver cavernous hemangioma. Sclerosing cholangitis (SC) is a rare complication occurring after TACE. Operative exploration was indicated for our patient as preoperative imaging examination could not exclude the possibility of malignant hilar biliary stricture. Diagnosis of SC depends on the presence of chronic inflammation of the bile duct with characteristic features of sclerosis after primary SC is ruled out. Definitive treatment included radical hepatic hilar resection with hepatectomy and bile duct reconstruction.

- Citation: Jin S, Shi XJ, Sun XD, Wang SY, Wang GY. Sclerosing cholangitis secondary to bleomycin-iodinated embolization for liver hemangioma. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(46): 17680-17685

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i46/17680.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17680

Liver cavernous hemangioma (LCH) is the most common benign liver tumor, with a prevalence of 0.4%-7.3% in the general population based on autopsy findings[1] and an obvious female dominance (male:female = 1:5)[2]. Treatment modalities for LCH consist mainly of observation, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE)[3], surgical resection[4], and even liver transplantation[5]. Surgical resection is normally indicated for patients who exhibit clinically significant symptoms, complications, or non-excludable malignancy[4].

TACE is an interventional radiology technique that has been well established in the minimally invasive treatment of benign and malignant liver tumors. This non-surgical intervention can control liver disease by interrupting the blood flow of the nourishing arteries and shows a generally favorable safety profile in the current literature[6]. Common embolic agents include morrhuate sodium, anhydrous ethanol, and bleomycin-iodinated oil (BIO). BIO is typically preferred over morrhuate sodium and anhydrous ethanol for treating LCH, because the latter two potent angiosclerotic agents can result in massive injury of vascular endothelia and secondary intravascular thrombosis[7,8]. In contrast, BIO is relatively less potent in inducing arterial embolization, and BIO embolization-associated morbidities are rarely reported[9].

Sclerosing cholangitis (SC) is a chronic biliary condition characteristic of progressive bile duct inflammation, fibrosis, destruction, and cholestasis, which may occur idiopathically in the form of primary SC in most cases but also occasionally occurs secondary to biliary calculosis, hepatobiliary surgery, malignant obstruction of bile duct, recurrent pancreatitis, or intra-arterial chemotherapy[10]. Herein, we report a case of SC secondary to TACE with BIO in a middle-aged woman with symptomatic LCH. This patient presented with progressive obstructive jaundice and concomitant intrahepatic bile duct dilation. An explorative operation along with histological findings excluded the possibility of biliary malignancy, and secondary SC resolved after hemihepatectomy with bile duct plasty.

A 44-year-old woman complained of a 6-mo history of recurrent yellowish colorization of the skin and sclera with upper abdominal distension but without fever or abdominal pain. Jaundice and abdominal distension worsened progressively with a 2-kg weight loss but without obvious causes over 1 mo. Six years prior to presentation in our department, the patient had previously undergone TACE with BIO 6 years before admission for a symptomatic LCH with a size of 7 cm × 9 cm and located at segment VII. LCH-associated symptoms resolved after TACE, and the patient complained of no discomfort but was lost to follow-up. Later the patient was referred to our surgical service due to a suspected bile duct obstruction.

On admission, physical examination showed that the skin and sclera were mildly jaundiced, and the abdominal wall was soft with mild upper abdominal tenderness. Clinical liver biochemistry assay results were as follows: serum alanine aminotransferase, 24 U/L (reference limit, 5-40 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 53 U/L (0-40 U/L); gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, 263 U/L (5-55 U/L); alkaline phosphatase, 263 U/L (40-150 U/L); total serum bilirubin, 107 μmol/L (1.7-17.1 μmol/L); unconjugated bilirubin, 22 μmol/L (1.7-13.7 μmol/L); conjugated bilirubin, 85 μmol/L (1-4 μmol/L); serum tumor biomarker and alpha-fetal protein, 6.5 U/L (< 25 U/L); and cancer antigen 19-9 60.4 U/L (0-39 U/mL).

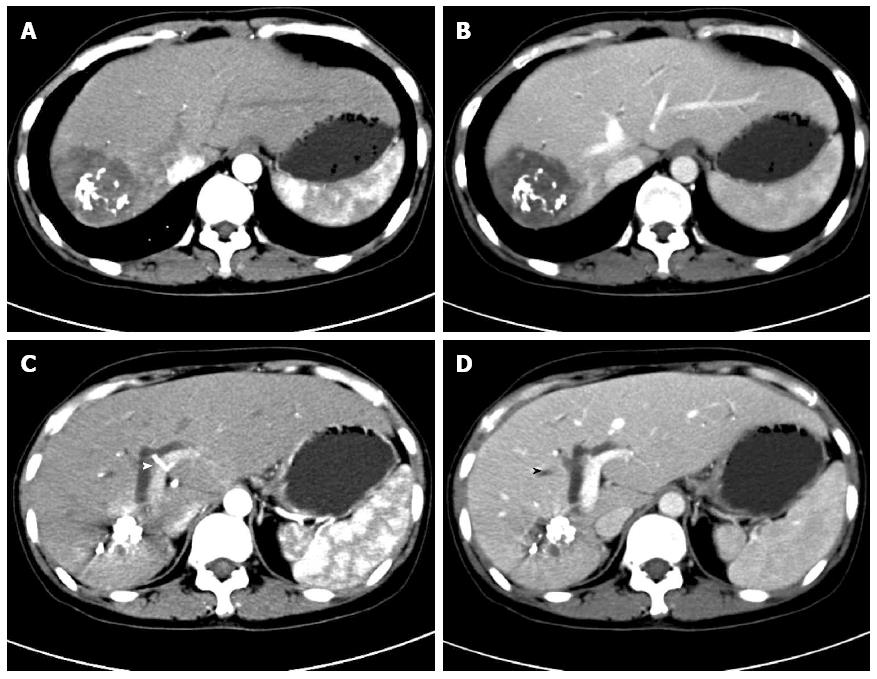

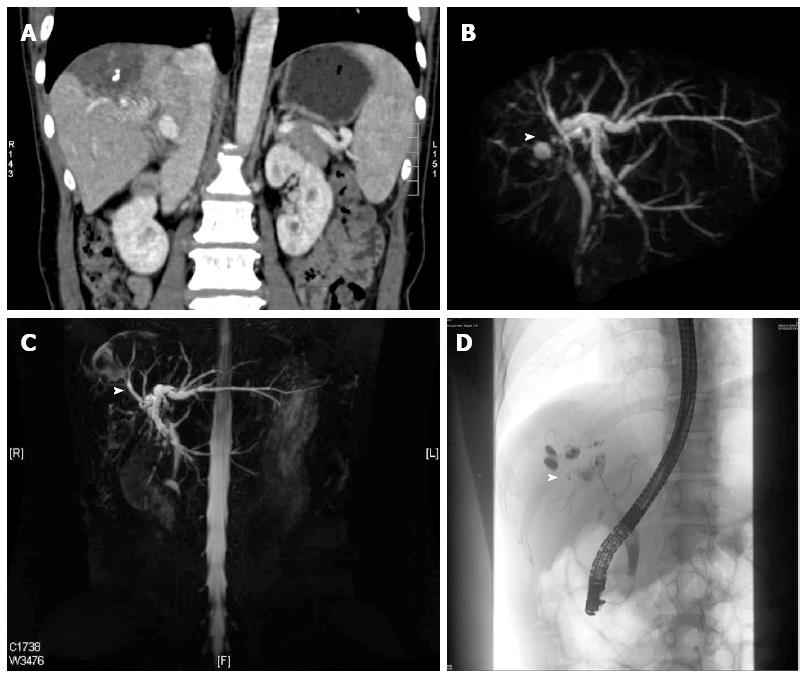

Contrast-enhanced upper abdominal computed tomography showed BIO deposition in the right lobe without evident liver parenchymal fibrosis, significant dilation of intrahepatic bile ducts proximal to the convergence of the left and right hepatic ducts at the portal area, and calculous cholecystitis (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography at the gastroenterology outpatient clinic showed gallstones of the common bile duct (Figure 2). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with nasal biliary drainage was performed, and a small amount of bile sludge was removed. However, the symptoms did not improve significantly (Figure 3).

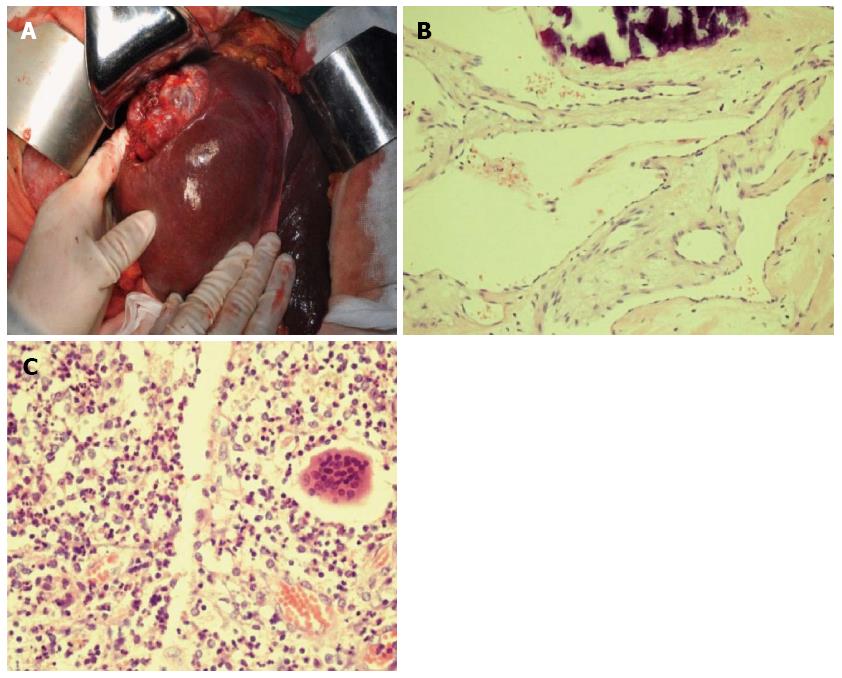

Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage was rejected by the patient, but operative exploration was scheduled because hilar bile duct cancer could not be excluded after the patient provided voluntary informed consent. The liver showed no sign of fibrosis or cirrhosis; the right lobe was significantly atrophic, but the left lateral and medial lobes exhibited obvious hyperplasia. The hilum showed an obvious shift towards the right side. A projecting, reddish LCH was located in the right posterior lobe involving segments VI and VII, at a size of 6 cm × 4 cm, with a rough surface and rigid contour (Figure 3A). The gallbladder was completely atrophic, at a size of 1 cm × 41 cm. Exploration of the common bile revealed that the distal hepatic ducts had a full-thickness rigid wall without any palpable lumen. The envelopment of the hilum did not allow exploration beyond the distal hepatic ducts. Cholangioscopy showed no stricture or gallstones in the distal segment of the common bile duct (CBD) but a severe regional stricture at the hilar level. After biliary dilation, repeated cholangioscopy showed that the left hepatic duct was patent but mildly dilated beyond the stricture; the right hepatic duct was severely strictured, which blocked the passage of the cholangioscope. The common hepatic duct had a greyish, rigid internal lumen. Due to a highly suspicious biliary malignancy, right-side hemihepatectomy was performed to explore and resect the hilar bile duct disease. The possibility of malignancy could not be excluded based on frozen biopsy. The common hepatic duct and the CBD were further dissected towards the duodenum until the level of the middle segment of the CBD; the left hepatic duct was further mobilized towards the liver 1 cm beyond the stricture. Repeated frozen biopsy showed a clean resection margin. Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was performed to reconstruct the biliary drainage continuity.

The histological staining results showed chronic pyogenic inflammation of the bile duct, and a diagnosis of SC secondary to TACE with BIO was made (Figure 3B and C). The biopsy of the left lobe showed near normal histological results. The patient received postoperative symptom treatment and underwent an uneventful postoperative course. The liver function returned to normal on postoperative day 3. The patient was discharged home on postoperative day 8, and on follow-up examination at the outpatient clinic 4 mo after operation, the patient reported no discomfort.

Bleomycin is a cycle-nonspecific cytotoxic agent that degrades DNA through direct mechanisms. As a less potent angiosclerotic agent, bleomycin can also disrupt the tumor vascular lumen by gradually inducing a nonspecific inflammatory response around the tumor as well as in the portal area[11-13]. Iodinated oil exhibits a synergistic effect upon irradiation of the vascular wall and leads to mesenchymal hyperplasia and organization. The emulsion of BIO as an embolic agent can be retained in deformed vessels and disseminated through the microcirculation. TACE with BIO results in complete destruction of vascular endothelia and elimination of the pathologic vascular bed usually in a gradual, progressive manner. Previous studies showed that superselective embolization with BIO achieved a long-term reliable and safe treatment effect for LCH[9,13].

TACE with BIO is inevitably associated with some procedural risks, including acute liver failure, liver infarction or abscess, intrahepatic biloma, multiple intrahepatic aneurysms, cholecystitis, splenic infarction, and hepatic artery perforation or rupture[14]. However, the aforementioned complications usually occur within a short time rather than a long time after TACE. Huang et al[14] reported biliary destruction after TACE with morrhuate sodium and anhydrous ethanol, which manifested as aggressive abdominal pain, high fever, and jaundice. In contrast, our patient sought medical treatment due to clinically significant jaundice 6 years after previous TACE. Subclinical jaundice remained undetected in this patient because she had been lost to follow-up.

The bile ducts almost completely depend on the hepatic artery for their blood supply. The small branches originating from the hepatic artery anastomose with each other and form a peri-duct vascular plexus along the outer layer and submucosal tissue of the bile ducts. In comparison with liver cells, which are nourished by two blood supplies, biliary endothelial cells are relatively sensitive to hepatic artery embolization[11,15]. Hepatic artery embolization will interrupt the blood supply to the bile ducts and the portal areas and lead to ischemia, degeneration, and necrosis of the bile duct wall The hilar bile duct is even more prone to ischemia from hepatic artery embolization as the middle and distal segments of the CBD have some collateral circulation from the gastroduodenal and posterior duodenal arteries. Hepatic artery embolization with BIO resulted in a chronic, nonspecific, thrombotic inflammation of the arteries in the portal area, bile ducts, and gallbladder in this patient, and interruption of blood flow and dissemination of vasculitis led to secondary SC with complicating obstructive jaundice.

The differential diagnosis of secondary SC depends on delineating the etiology of SC, specifically excluding possible bile duct malignancy. This patient remained generally well except for being jaundiced; her asymptomatic jaundice showed a chronic, recurrent course with a fluctuating total bilirubin level between 37 mmol/L and 107 mmol/L, in contrast to progressive jaundice in malignant bile duct obstruction. Hepatobiliary imaging investigation showed that the suspected hilar tumor was mainly involved the right hepatic duct, whereas the left hepatic duct was relatively well preserved, unlike that seen in common hilar cancer. Mild elevation in serum cancer antigen 19-9 also can be seen in patients with chronic cholangitis. Due to the history of previous TACE, a diagnosis of SC secondary to BIO TACE was made in combination with imaging investigation and surgically explorative findings.

Some authors have proposed that no hepatectomy is required for patients suffering from biliary destruction after TACE and that hepaticojejunostomy with U-tube stenting is preferred for reconstruction of biliary drainage[15]. However, right-side hemihepatectomy with biliary plasty was performed in this patient based on the following considerations. First, the presence of a large amount of residual embolic agent might continue to aggravate pre-existing injuries of biliary vessels and bile ducts. Second, the pre-existing cholangitis was refractory to medical and endoscopic treatment and likely to progress into serious ascending cholangitis and intrahepatic abscess. Lastly, simply U-tube stenting could not eliminate the cause of secondary SC and subsequently failed to improve or control pre-existing SC.

Unlike primary SC, which eventually requires liver transplantation, secondary SC normally exhibits a favorable prognosis if the etiological causes are completely eliminated. Recurrence of secondary SC may occur if the underlying cause is in relapse or beyond control. Our short-term follow-up results showed that the patient returned to a good health status after the definitive surgery. However, the outcome of secondary SC reported in a retrospective case series of 31 patients was discouraging[16]. We considered that liver fibrosis or cirrhosis after secondary SC are irreversible and a patient with uncompensated liver function also requires liver transplantation with a poor transplant-free survival. Long-term follow-up is essential for our patient, although she exhibited no signs of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis 4 mo after operation.

A 44-year-old woman with a history of liver cavernous hemangioma presenting with obstructive jaundice 6 years after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) with bleomycin-iodinated oil (BIO).

The skin and sclera of the patient were mildly jaundiced, and the abdominal wall was soft with mild upper abdominal tenderness.

Hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Aspartate aminotransferase 53 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase 263 U/L, total serum bilirubin 107 μmol/L, conjugated bilirubin 85 μmol/L; alpha-fetal protein 6.5 U/L (< 25 U/L) and cancer antigen 19-9 60.4 U/L (0-39 U/mL).

3D-MRCP confirmed the dilation of the left hepatic duct and the narrowing of the right hepatic duct, and a soft tissue-like mass was located at the convergence of the left and right hepatic ducts.

Histology showed chronic pyogenic inflammation of the bile duct, and a diagnosis of sclerosing cholangitis (SC) secondary to TACE with BIO was made.

The patient was treated with FOLFOX (5-FU, oxaliplatin and leucovorin) in combination with bevacizumab.

Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was performed to maintain biliary drainage continuity.

Hepatic duct plasty is a definitive but technically challenging treatment modality for hilar secondary SC.

This case report demonstrates that secondary SC after TACE, manifesting as asymptomatic obstructive jaundice, must be differentiated from hilar bile duct malignancy. Hemihepatectomy with hepaticojejunostomy is a definitive and preferred treatment option for secondary SC.

This paper is very interesting. There is no problem to publish the manuscript.

P- Reviewer: Chen YC, Yoshida H S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Brouwers MA, Peeters PM, de Jong KP, Haagsma EB, Klompmaker IJ, Bijleveld CM, Zwaveling JH, Slooff MJ. Surgical treatment of giant haemangioma of the liver. Br J Surg. 1997;84:314-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | van Malenstein H, Maleux G, Monbaliu D, Verslype C, Komuta M, Roskams T, Laleman W, Cassiman D, Fevery J, Aerts R. Giant liver hemangioma: the role of female sex hormones and treatment. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:438-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Akamatsu N, Sugawara Y, Komagome M, Ishida T, Shin N, Cho N, Ozawa F, Hashimoto D. Giant liver hemangioma resected by trisectorectomy after efficient volume reduction by transcatheter arterial embolization: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bioulac-Sage P, Laumonier H, Laurent C, Blanc JF, Balabaud C. Benign and malignant vascular tumors of the liver in adults. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:302-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhong L, Men TY, Yang GD, Gu Y, Chen G, Xing TH, Fan JW, Peng ZH. Case report: living donor liver transplantation for giant hepatic hemangioma using a right lobe graft without the middle hepatic vein. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Giavroglou C, Economou H, Ioannidis I. Arterial embolization of giant hepatic hemangiomas. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26:92-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Choi BY, Nguyen MH. The diagnosis and management of benign hepatic tumors. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:401-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Federle MP, Brancatelli G, Blachar A. Hepatic hemangioma. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:368-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zeng Q, Li Y, Chen Y, Ouyang Y, He X, Zhang H. Gigantic cavernous hemangioma of the liver treated by intra-arterial embolization with pingyangmycin-lipiodol emulsion: a multi-center study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:481-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Qu K, Liu C, Wu QF, Wang B, Mansoor AM, Qin H, Ma Q, Liu YM. Sclerosing cholangitis after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization: a case report. Chin Med Sci J. 2011;26:190-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schnelldorfer T, Ware AL, Smoot R, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Nagorney DM. Management of giant hemangioma of the liver: resection versus observation. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:724-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Herman P, Costa ML, Machado MA, Pugliese V, D’Albuquerque LA, Machado MC, Gama-Rodrigues JJ, Saad WA. Management of hepatic hemangiomas: a 14-year experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:853-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Oda K, Matoba Y, Noda M, Kumagai T, Sugiyama M. Catalytic mechanism of bleomycin N-acetyltransferase proposed on the basis of its crystal structure. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:1446-1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Huang XQ, Huang ZQ, Duan WD, Zhou NX, Feng YQ. Severe biliary complications after hepatic artery embolization. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:119-123. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Terblanche J, Allison HF, Northover JM. An ischemic basis for biliary strictures. Surgery. 1983;94:52-57. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Gossard AA, Angulo P, Lindor KD. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis: a comparison to primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1330-1333. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |