Published online Dec 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17127

Revised: May 24, 2014

Accepted: July 24, 2014

Published online: December 7, 2014

Processing time: 299 Days and 19.7 Hours

AIM: To clarify the efficacy of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) after endoscopic variceal obturation (EVO) with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate.

METHODS: A retrospective study was performed on 16 liver cirrhosis patients with gastric variceal bleeding that received EVO with injections of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate at a single center (Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong) from January 2008 to December 2012. Medical records including patient characteristics and endoscopic findings were reviewed. Treatment results, liver function, serum biochemistry and cirrhosis etiology were compared between patients receiving PPIs and those that did not. Furthermore, the rebleeding interval was compared between patients that received PPI treatment after EVO and those who did not.

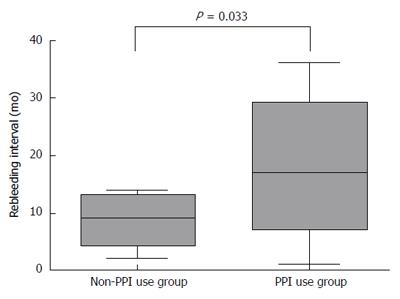

RESULTS: The patient group included nine males and seven females with a mean age of 61.8 ± 11.7 years. Following the EVO procedure, eight of the 12 patients that received PPIs and three of the four non-PPI patients experienced rebleeding. There were no differences between the groups in serum biochemistry or patient characteristics. The rebleeding rate was not significantly different between the groups, however, patients receiving PPIs had a significantly longer rebleeding interval compared to non-PPI patients (22.2 ± 11.2 mo vs 8.5 ± 5.5 mo; P = 0.008). The duration of PPI use was not related to the rebleeding interval. A total of six patients, who had ulcers at the injection site, exhibited a shorter rebleeding interval (16.8 ± 5.9 mo) than patients without ulcers (19.9 ± 3.2 mo), though this difference was not statistically significant.

CONCLUSION: PPI therapy can extend the rebleeding interval, and should therefore be considered after EVO treatment for gastric varices.

Core tip: Endoscopic variceal obturation (EVO) with N-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate is a first-line treatment for gastric variceal bleeding. Although proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are administered to decrease the adverse effects of endoscopic variceal ligation, their effects following EVO for gastric varices are unclear. In this study, patients who received PPI therapy had a longer rebleeding interval after EVO with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate, suggesting it has beneficial effects for gastric variceal bleeding.

- Citation: Jang WS, Shin HP, Lee JI, Joo KR, Cha JM, Jeon JW, Lim JU. Proton pump inhibitor administration delays rebleeding after endoscopic gastric variceal obturation. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(45): 17127-17131

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i45/17127.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17127

Bleeding from gastric varices (GV) is difficult to control and is associated with a high risk for rebleeding and high mortality[1]. Fundic varices, increasing variceal size, presence of a red spot, and advanced liver disease are all associated with a high risk for hemorrhage and gastric variceal bleeding[2,3]. Although control of variceal bleeding has improved over the past two decades, it is still the most serious and fatal complication of portal hypertension and chronic liver disease[4-6]. Current methods to manage and prevent GV bleeding include endoscopic treatments such as sclerotherapy and band ligation, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts, and balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration. Of these, endoscopic variceal obturation (EVO) with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl) can be performed as a first-line treatment[7]. The first report on the use of tissue adhesive agents to control GV bleeding was by Soehendra et al[8] in 1986 The injection of a cyanoacrylate can produce primary hemostasis in 70%-95% of patients with acute GV bleeding, with an early rebleeding rate that ranges from 0% to 28% within 48 h[9-11], though with complications such as delayed bleeding or rebleeding due to glue cast, ulcer, infection, and embolism[12].

Bleeding from the ulcer after EVO occurs in up to 13% of patients[13-15]. Studies have shown that antacid use can improve post-injection ulcers in the esophagus, and also suggest that proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) could be used to treat post-sclerotherapy ulcers complicated by bleeding[16-20]. However, there are few reports that address the effectiveness of PPIs for GV treated by injection therapy. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to retrospectively evaluate the association between the rebleeding interval and the use of PPIs after EVO.

A total of 16 patients who underwent EVO for GV bleeding at the Kyung Hee University Hospital between January 2008 and December 2012 were retrospectively enrolled in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1989) of the World Medical Association. PPI administration and duration were randomly determined according to each patient’s physician. Three kinds of full dose PPIs including 40 mg pantoprazole, 20 mg rabeprazole, and 20 mg omeprazole were orally administered every day. Patients with a history of vascular anastomosis, portal vein thrombosis, liver transplantation, hepatocellular carcinoma, pregnancy, allergies or past adverse reactions to PPIs were excluded. Medical records were reviewed and the following data were collected: (1) patient characteristics, such as age and sex; (2) serum biochemistry, including total bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time, and creatinine level; (3) etiology of liver cirrhosis; (4) endoscopy findings; (5) procedure-related complications and mortality; (6) type and dose of PPI; and (7) rebleeding rate and time.

A cyanoacrylate injection was performed using a GIF-H 260 (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) or EG-590WR (Fujinon Inc., Saitama, Japan) endoscope and a 23-gauge disposable injection needle catheter (1650 or 1800 mm in length). Injections included 1 cc of cyanoacrylate (B. Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany) and 1 cc of lipiodol (Guerbet, Villepinte, France). Saline was administered through the catheter to deliver the glue mixture into the varices, and the needle was removed while the glue was flowing in order to decrease the risk of needle embedment. The catheter was then flushed with sterile water. The total amount of mixture used for EVO therapy was decided by an expert endoscopist with consideration of the type and size of varices. All procedures were performed by one expert endoscopist (HP Shin).

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 18; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). A Student’s t-test was used for comparison of quantitative variables, and χ2 test and Fisher’s exact tests were used for qualitative variables. Results are expressed as the mean ± SD for continuous variables and as a number (percentage) for categorical data. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Of the 16 patients enrolled, nine (56.3%) were male and seven (43.7%) were female, with a mean age of 61.8 ± 11.7 years. The mean model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score for all patients was 14.6 ± 4.9, with hepatitis B as the most common etiology of liver cirrhosis (6/16, 37.5%), followed by alcoholic liver cirrhosis (5/16, 31.3%), cryptogenic cirrhosis (4/16; 25.0%), and chronic hepatitis C (1/16, 6.3%). The overall average results from blood tests were: total bilirubin, 1.8 ± 1.6 mg/dL; albumin, 2.8 ± 0.5 g/dL; prothrombin time (international normalized ratio), 1.6 ± 0.4; creatinine, 1.1 ± 0.3 mg/dL. The rebleeding interval after the procedure was 18.8 ± 11.6 mo. Successful hemostasis was defined as vital sign stability, no decrease in hemoglobin and no rebleeding within 24 h after EVO. No serious postoperative complications were observed, such as distant embolization, sepsis, mesentery hematoma or hemoperitoneum, and no patient deaths occurred during hospitalization.

The PPI use group (n = 12) following EVO received a full dose of PPI orally every morning for an average of 11.7 wk. Eight of the 12 patients that received PPIs and three of the four non-PPI patients experienced rebleeding. The group that received PPIs had a significantly longer rebleeding interval compared to those that did not (22.2 ± 11.2 mo vs 8.5 ± 5.5 mo; P = 0.008) (Figure 1). Although the mean patient age in the PPI group was older, the difference was not significant. Six patients had ulcers at a previous injection site. The rebleeding interval for cases of GV with ulcers was 16.8 ± 5.9 mo, which was shorter than, but not significantly different from, patients without ulcers (19.9 ± 3.2 mo). Furthermore, the rebleeding interval was not associated with the duration of PPI use (data not shown). There were no differences between patients treated with or without PPIs in bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time, creatinine levels or MELD score (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Non-PPI group | PPI group | P-value |

| Age (yr) | 55.3 ± 2.1 | 63.4 ± 3.7 | 0.075 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 0.652 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 0.579 |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 0.721 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.936 |

| MELD score | 15.8 ± 3.2 | 14.2 ± 1.3 | 0.671 |

Portal hypertension can result in the formation of gastric and esophageal varices. Many patients with cirrhosis experience an increase in the number of varices during their lifetime. GV are present in 30% of patients with compensated cirrhosis, and up to 60% of patients with decompensated cirrhosis, at the time of diagnosis[21]. Variceal growth accompanies the progression of liver failure, with esophageal varices progressing at rate of 9% per year in patients with cirrhosis[22]. Christensen et al[23] reported that detection of esophageal varices in a cirrhotic cohort increased from 12% to 90% over ten years.

Variceal bleeding is associated with a morality rate of 30%-50%. A majority of survivors will experience rebleeding, and a large percentage will die in the year following an episode[24,25]. Although bleeding occurs less frequently in gastric compared to esophageal varices, GV bleeding tends to be more severe, requiring more red blood cell transfusions and with a higher mortality rate[1]. Numerous studies have indicated that treatment of GV with EVO and cyanoacrylate injection resulted in a hemostasis ranging from 58% to 100% and a rebleeding rate of 0%-40%[2,9,26-33], with a reported 28.5% of patients experiencing rebleeding within the first year[34], though one study reported that half of patients with poor hepatic function experienced rebleeding within the first 6 wk[4]. Rebleeding can occur if the obturation is incomplete, or if the glue cast breaks down before the variceal fibrosis matures. The rebleeding rate can be reduced by complete variceal obliteration, assessed by careful palpation with the injector, ensuring that only drops of glue and blood effuse from the injection site after retraction of the injector, or by computed tomography 3-5 d after the procedure. Obstruction of the vessel by the injected cyanoacrylate induces an inflammatory response followed by chronic granuloma formation and fibrosis due to the extrusion of the glue through previously embolized vessels[35].

In this study, we observed that extravascular injection of a mixture of cyanoacrylate and lipiodol produced oval-shaped polymerization products with irregular margins. These submucosal glue polymers can induce caseous necrosis[36] and explain the occurrence of gastric ulceration[37]. This ulcer type has a high probability of vessel exposure, and the abundance of vessels in the stomach wall can increase the severity and prolong the inflammation. Furthermore, exposure to gastric acid may suppress ulcer healing[38]. Therefore, adjuvant therapy with PPIs, the most potent pharmacologic agents for inhibiting gastric acid secretion[39] may prove to be beneficial for GV patients. Patients with ulcers in this study showed shorter rebleeding intervals compared to those without, although the small number of cases prevented this difference from achieving significance. Overall, however, the results of this study support the use of acid suppression therapy, which delayed GV rebleeding after EVO.

This study has some limitations, including a possibility of selection bias due to the retrospective design, such as a bias for PPI use based on the clinician’s subjective findings. However, the potential for recall bias was substantially reduced as all the data were recorded immediately after individual treatment. This study group size was too small to properly evaluate different PPIs, or their duration of use. Therefore, additional prospective studies with a larger population should be used to further elucidate the benefits and effectiveness of various PPI therapies in patients with GV treated by EVO.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are widely used after endoscopic variceal ligation. Endoscopic variceal obturation (EVO) can be performed for gastric variceal bleeding, but little is known about the effect of PPIs after EVO.

Gastric variceal bleeding is challenging to control and is associated with a high risk for rebleeding. Therapies that include the use of PPIs to prevent bleeding after EVO are gaining popularity, and thus research clarifying their efficacy is needed.

In several studies, the use of antacids after sclerotherapy was shown to improve post-injection esophageal ulcers, but has not been well studied for treatment of gastric varices. Despite the limited number of patients, this study suggests that PPIs may delay rebleeding caused by endoscopic sclerotherapy.

EVO with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate can be performed as a first-line treatment for gastric varices. However, rebleeding at the injection site can occur after EVO. Although PPIs may help to minimize rebleeding, their use after EVO has not been well studied. The results of the present study indicate that patients receiving EVO for treatment of gastric varices show delayed rebleeding with PPI use.

PPIs inhibit gastric hydrogen potassium ATPases and are potent inhibitors of gastric acid secretion. EVO consists of the injection of tissue adhesive agents into the varices for the occlusion of vessels. N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate is an injectable liquid material that when polymerized provides strong tension that can be used to control bleeding from vascular structures.

The authors examined PPI therapy in patients undergoing EVO for treatment of gastric varices. The results are especially useful for endoscopists, as there are currently no specific guidelines concerning PPI usage after EVO. The results suggest that PPIs can delay rebleeding, and indicate that larger, prospective studies are warranted to further evaluate these beneficial effects.

P- Reviewer: Karsan H, Maluf-Filho F, Sato T S- Editor: Ma N L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, Murthy NS, Makwana UK. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: a long-term follow-up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology. 1992;16:1343-1349. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Sarin SK, Jain AK, Jain M, Gupta R. A randomized controlled trial of cyanoacrylate versus alcohol injection in patients with isolated fundic varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1010-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kind R, Guglielmi A, Rodella L, Lombardo F, Catalano F, Ruzzenente A, Borzellino G, Girlanda R, Leopardi F, Pratticò F. Bucrylate treatment of bleeding gastric varices: 12 years’ experience. Endoscopy. 2000;32:512-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Marques P, Maluf-Filho F, Kumar A, Matuguma SE, Sakai P, Ishioka S. Long-term outcomes of acute gastric variceal bleeding in 48 patients following treatment with cyanoacrylate. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:544-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bhasin DK, Siyad I. Variceal bleeding and portal hypertension: new lights on old horizon. Endoscopy. 2004;36:120-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lunderquist A, Börjesson B, Owman T, Bengmark S. Isobutyl 2-cyanoacrylate (bucrylate) in obliteration of gastric coronary vein and esophageal varices. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1978;130:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1229] [Cited by in RCA: 1210] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Soehendra N, Nam VC, Grimm H, Kempeneers I. Endoscopic obliteration of large esophagogastric varices with bucrylate. Endoscopy. 1986;18:25-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Noophun P, Kongkam P, Gonlachanvit S, Rerknimitr R. Bleeding gastric varices: results of endoscopic injection with cyanoacrylate at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7531-7535. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kojima K, Imazu H, Matsumura M, Honda Y, Umemoto N, Moriyasu H, Orihashi T, Uejima M, Morioka C, Komeda Y. Sclerotherapy for gastric fundal variceal bleeding: is complete obliteration possible without cyanoacrylate? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1701-1706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hashizume M, Sugimachi K. Classification of gastric lesions associated with portal hypertension. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;10:339-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cheng LF, Wang ZQ, Li CZ, Lin W, Yeo AE, Jin B. Low incidence of complications from endoscopic gastric variceal obturation with butyl cyanoacrylate. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:760-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Schuman BM, Beckman JW, Tedesco FJ, Griffin JW, Assad RT. Complications of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:823-830. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sauerbruch T, Weinzierl M, Köpcke W, Paumgartner G. Long-term sclerotherapy of bleeding esophageal varices in patients with liver cirrhosis. An evaluation of mortality and rebleeding risk factors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1985;20:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Palani CK, Abuabara S, Kraft AR, Jonasson O. Endoscopic sclerotherapy in acute variceal hemorrhage. Am J Surg. 1981;141:164-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Paquet KJ, Koussouris P, Keinath R, Rambach W, Kalk JF. A comparison of sucralfate with placebo in the treatment of esophageal ulcers following therapeutic endoscopic sclerotherapy of esophageal varices--a prospective controlled randomized trial. Am J Med. 1991;91:147S-150S. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Roark G. Treatment of postsclerotherapy esophageal ulcers with sucralfate. Gastrointest Endosc. 1984;30:9-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Polson RJ, Westaby D, Gimson AE, Hayes PC, Stellon AJ, Hayllar K, Williams R. Sucralfate for the prevention of early rebleeding following injection sclerotherapy for esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1989;10:279-282. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Gimson A, Polson R, Westaby D, Williams R. Omeprazole in the management of intractable esophageal ulceration following injection sclerotherapy. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1829-1831. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Tamura S, Shiozaki H, Kobayashi K, Yano H, Tahara H, Miyata M, Mori T. Prospective randomized study on the effect of ranitidine against injection ulcer after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for esophageal varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:477-480. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Dagher L, Burroughs A. Variceal bleeding and portal hypertensive gastropathy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Merli M, Nicolini G, Angeloni S, Rinaldi V, De Santis A, Merkel C, Attili AF, Riggio O. Incidence and natural history of small esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2003;38:266-272. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Christensen E, Fauerholdt L, Schlichting P, Juhl E, Poulsen H, Tygstrup N. Aspects of the natural history of gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhosis and the effect of prednisone. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:944-952. [PubMed] |

| 24. | D’Amico G, Luca A. Natural history. Clinical-haemodynamic correlations. Prediction of the risk of bleeding. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;11:243-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Graham DY, Smith JL. The course of patients after variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:800-809. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Chen MH, Chiang HT. A prospective, randomized trial of butyl cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation in the management of bleeding gastric varices. Hepatology. 2001;33:1060-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sarin SK. Long-term follow-up of gastric variceal sclerotherapy: an eleven-year experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:8-14. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Soehendra N, Grimm H, Nam VC, Berger B. N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate: a supplement to endoscopic sclerotherapy. Endoscopy. 1987;19:221-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Huang YH, Yeh HZ, Chen GH, Chang CS, Wu CY, Poon SK, Lien HC, Yang SS. Endoscopic treatment of bleeding gastric varices by N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl) injection: long-term efficacy and safety. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:160-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lee YT, Chan FK, Ng EK, Leung VK, Law KB, Yung MY, Chung SC, Sung JJ. EUS-guided injection of cyanoacrylate for bleeding gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Dhiman RK, Chawla Y, Taneja S, Biswas R, Sharma TR, Dilawari JB. Endoscopic sclerotherapy of gastric variceal bleeding with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:222-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Akahoshi T, Hashizume M, Shimabukuro R, Tanoue K, Tomikawa M, Okita K, Gotoh N, Konishi K, Tsutsumi N, Sugimachi K. Long-term results of endoscopic Histoacryl injection sclerotherapy for gastric variceal bleeding: a 10-year experience. Surgery. 2002;131:S176-S181. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Mostafa I, Omar MM, Nouh A. Endoscopic control of gastric variceal bleeding with butyl cyanoacrylate in patients with schistosomiasis. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1997;27:405-410. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Caldwell SH, Hespenheide EE, Greenwald BD, Northup PG, Patrie JT. Enbucrilate for gastric varices: extended experience in 92 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:49-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Brothers MF, Kaufmann JC, Fox AJ, Deveikis JP. n-Butyl 2-cyanoacrylate--substitute for IBCA in interventional neuroradiology: histopathologic and polymerization time studies. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1989;10:777-786. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Kunstlinger F, Brunelle F, Chaumont P, Doyon D. Vascular occlusive agents. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;136:151-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Woodward SC, Herrmann JB, Cameron JL, Brandes G, Pulaski EJ, Leonard F. Histotoxicity of cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive in the rat. Ann Surg. 1965;162:113-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Shaheen NJ, Stuart E, Schmitz SM, Mitchell KL, Fried MW, Zacks S, Russo MW, Galanko J, Shrestha R. Pantoprazole reduces the size of postbanding ulcers after variceal band ligation: a randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology. 2005;41:588-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Boparai KS, Dekker E, Van Eeden S, Polak MM, Bartelsman JF, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Keller JJ, van Noesel CJ. Hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenomas as a phenotypic expression of MYH-associated polyposis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:2014-2018. [PubMed] |