Published online Nov 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16191

Revised: June 18, 2014

Accepted: July 15, 2014

Published online: November 21, 2014

Processing time: 231 Days and 18.5 Hours

In the last decades, the treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts and necrosis occurring in the clinical context of acute and chronic pancreatitis has shifted towards minimally invasive endoscopic interventions. Surgical procedures can be avoided in many cases by using endoscopically placed, Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided techniques and drainages. Endoscopic ultrasound enables the placement of transmural plastic and metal stents or nasocystic tubes for the drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections. The development of self-expanding metal stents and exchange free delivering systems have simplified the drainage of pancreatic fluid collections. This review will discuss available therapeutic techniques and new developments.

Core tip: Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts and walled-off necrosis has become an established less invasive management of these difficult to treat complications of acute and chronic pancreatitis. New developments such as forward-viewing echoscopes and exchange-free delivery systems for the insertion of stents and drainages have simplified the technically challenging procedure. Specially designed self-expanding metal stents aim on improved drainage of the cyst content. This article reviews new EUS-guided techniques and their indications.

- Citation: Braden B, Dietrich CF. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided endoscopic treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts and walled-off necrosis: New technical developments. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(43): 16191-16196

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i43/16191.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16191

Peripancreatic fluid collections frequently occur in the context of acute and chronic pancreatitis. Fortunately, more than 50% will resolve spontaneously and, therefore, a conservative expectant approach is often the right clinical decision.

The updated Atlanta classification[1] tries to overcome the existing confusion in reporting morphologic features and complications of pancreatitis. The revised definitions differ between acute peripancreatic fluid collections associated with acute interstitial oedematous pancreatitis and acute necrotic collection occurring in necrotising pancreatitis in the acute phase. On the other hand in the late phase after more than 4 wk, the classifications describes pancreatic pseudocysts developing from interstitial oedematous pancreatitis or walled-off necrosis resulting from necrotizing pancreatitis (Table 1).

| Acute phase < 4 wk | Late phase > 4 wk | |

| Interstitial oedematous pancreatitis | Acute peripancreatic fluid collection (homogenous with fluid density, no definable wall, no necrosis, adjacent to pancreas, not intra-pancreatic) | Pancreatic pseudocyst (well circumscribed, usually round or oval, homogenous fluid density, no debris, well defined wall) |

| Necrotising pancreatitis | Acute necrosis (heterogenous and also non-liquid density, no definable wall, intra- and/or extrapancreatic location) | Walled-off necrosis (heterogenous and also non-liquid density, well defined wall, completely encapsulating, intra- and/or extrapancreatic location) |

Only superinfected or clinically symptomatic pseudocysts should be considered for interventional treatment. Infection, pain, malnutrition or compression of biliary, intestinal or vascular structures might present an indication for endoscopic or percutaneous drainage. The size of the cyst alone should not influence the decision for interventional treatment.

Apart from external and transmural endoscopic drainages, some pseudocysts with communication to the pancreatic duct might be suitable for transpapillary drainage via endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP). It is also possible to combine percutaneous and transmural drainages to allow frequent flushing through the external drain; similar techniques also exist for necrosectomy (hybride necrosectomy)[2,3].

Infected pseudocysts, pancreatic abscesses and infected necrosis often require drainage. Preferably, the intervention should be delayed to at least 4 wk or longer - if possible - after disease onset to allow demarcation and liquidification of the necrosis. Despite all enthusiasm for new technical developments and minimal invasive techniques, we should not forget that conservative management with antibiotic therapy alone can also result in a good outcome in selected, clinically stable patients[4-6]. Therefore, ideally, all decisions for intervention and when to intervene should be discussed in a multidisciplinary team.

Even in large bulging pseudocysts, the endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) guided drainage is superior to the purely endoscopic approach as the puncture of vascular structures can be avoided by Doppler sonographic visualization[7,8].

The puncture of the cyst is usually performed using a 19G needle under endosonographic view. Cyst content can be aspirated for biochemical analysis [amylase or lipase, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)], gram stain, culture and cytology. Through the lumen of the needle a 0.035” guide wire can be advanced until it curls up in the cyst which adds stabilisation of the position and access by forming anchoring extra loops in the cavity[9-11].

Enlargement of the newly created ostium can be achieved by balloon dilatation over the guide wire. Alternatively, the canal can be widened using a cytostome and diathermy. The cystotome also allows the direct puncture of the cyst as it contains an integrated needle knife catheter which can be used instead of the 19G needle but lacks stiffness. The outer metal ring of the cystotome allows application of diathermy and the creation of a 10 Fr channel.

Stents or nasocystic tubes can be placed over the guide wire. Usually, pigtail stents are preferred due to a reduced dislocation rate. The insertion of two or more stents is desirable to improve cyst drainage and to prevent occlusion of stent and ostium as the cyst content then also empties through the gaps between the stents. Direct insertion of two guide wires into the cyst through balloon catheter or cystotome before insertion of the first stent facilitates the placement of the second stent.

Recently, the so-called multiple transluminal gateway technique has been reported for treatment of walled-off necrosis. This method requires the EUS-guided creation of two or three transmural tracts between the necrotic cavity and the gastrointestinal lumen. While one tract is used to flush saline solution via a nasocystic catheter, multiple stents in the other tracts are deployed to facilitate drainage of necrotic contents. This method was superior compared to the conventional single tract technique and might avoid the need for endoscopic debridement or open surgery in some cases[12].

The EUS-guided stent placement can be performed by endosonographic and endoscopic visualization only, however, fluoroscopy is often helpful, especially as the endosonographic view can become difficult after the cyst puncture and during stent placement (Table 2).

| Ultrasound processor |

| Linear array echoscope with 3.8 mm instrument channel |

| 19 G EUS needle or cytostome and HF generator |

| Stiff guidewires (e.g., JagwireTM) |

| Dilatation balloon catheter |

| Pigtail prosthesis (e.g., 10 F) |

| Fluoroscopy optional |

It can be challenging to discriminate pseudocysts from benign and malignant cystic neoplasia. Morphological criteria including vascularized septa and solid nodules in the wall of the cyst are indicators for a cystic neoplasia. Contrast enhanced ultrasound has a major impact for the diagnostic workflow of pancreatic cystic lesions[13,14]. The biochemical analysis of the cystic fluid including amylase and the CEA has proved to be helpful in the differential diagnosis between mucinous tumours (IPMN and mucinous cystadenoma with high CEA) and pancreatic pseudocysts (high amylase and low CEA).

In case of extensive necrosis, it can be necessary to extract the necrotic tissue from the walled-off cyst in order to induce the healing process. This requires the creation of a large caliber transmural orifice between the gastric or duodenal and the cystic lumen which allows the passage of a standard endoscope into the cystic cavity. In 2000, Seifert reported the first three cases of endoscopic debridement of infected retroperitoneal necrosis[15]. Since then multicenter studies have proven reduced mortality and morbidity for endoscopic necrosectomy compared to the open surgical approach[16].

Conventional endoscopic snares and dormia baskets can be used to carefully extract the necrotic material into the stomach or duodenum. Usually, many repeated endoscopic sessions (on average 4 in a recent meta analysis[17]) are necessary to mobilise the necrotic tissue completely. Complications such as perforation (4%) and bleeding (18%) can occur during endoscopic necrosectomy. Particularily the bleeding can be horrendous because often large vessels transverse the cysts or necrotic cavity. Such procedures should only be undertaken by experienced endoscopic interventionalists in high volume centers that have back up by skilled hepatobiliopancreatic surgeons and interventional radiologists. In a recent meta analysis from 14 studies, more than 80% of patients with walled-off necrosis could be successfully treated by endoscopic necrosectomy alone; this was associated with 6% mortality and a complication rate at 36%[17].

Use of carbon dioxide insufflation is mandatory to avoid air embolism.

An echoendoscope with an antegrade view of 120 degree and 3.7 mm instrument channel has been designed by Olympus (TGF-UC260J) to improve the endoscopic orientation after the initial puncture facilitating further interventional steps such as dilatation or stent inserting. The straight instrument channel allows better instrument control due to reduced resistance. Compared to conventional linear echoscopes the antegrade type has curved linear array with a much shorter rigid portion at the tip and a capability to angulate the tip up to 180 degree which improves manoeuvrability and e.g., enables retroflexion in the fundus. An auxillary water channel flushes away blood and turbid cyst contents for clear endoscopic views.

First studies including a randomized controlled multicenter trial have shown promising results compared to conventional longitudinal echoendoscopes[18-20].

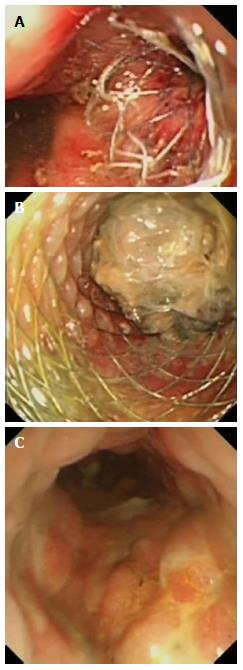

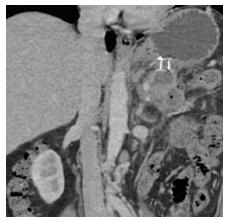

Usually, metal stents are not required to drain pseudocysts containing clear fluids but for infected cysts and walled-off necrosis a long term securing of a large diameter cyst opening by a metal stent can be helpful to allow drainage of larger particles and repeated direct endoscopic debridement (Figure 1). During the last years, self-expandable metal stents (SEMS) have been adapted to the needs of EUS guided cyst drainage. Large flanges should prevent dislocation of the stent, particularly feared is the migration of the stent into the necrotic cavity. The stents are covered to avoid leakage between cyst and stomach wall, it also prevents ingrowth and enables easy removal at a later timepoint. The self-extendable metal stents designed for drainage of pancreatic fluid collections and necrosis open to an internal diameter of more than 1 cm lumen to allow direct and repeated endoscopic access for endoscopic necrosectomy and extraction of necrotic tissue (Figure 2). The Axios stent (Xlumena™) and the Aix stent (Leufen™) are examples of such stents designed for EUS guided insertion, but also other companies are now producing similar stents. The covered stent produced by Hananro has extraflanges at the gastric end to stop migration into the cyst (Table 3).

| Stent | Company | Length (mm) | Internal diameter (mm) | Maximal flange diameter (mm) | Delivery device length (mm) | Delivery device diameter (Fr) |

| AxiosTM | Xlumena | 10 | 10 or 15 | 21 or 24 | 1460 | 10.8 |

| AixTM | Leufen | 30 | 10 or 15 | 25 | 2300 | 10 |

| NagiTM | Taewoong | 10 or 20 or 30 | 10 or 12 or 14 or 16 | 22 or 24 or 26 or 28 | 1800 | 10.5 |

| BCFTM Hanaro | M.I. Tech | 30 or 40 | 10 or 12 | 25 | 1800 | 10.2 |

The yo-yo-like design of the new SEMS such as the Axios™ stent results in a lumen apposing effect[21,22]. This can be adventageous in pancreatic fluid collections with indeterminate wall adherence.

Recent studies demonstrate a lower occlusion rate and the need for only one stent insertion due to the large diameter, the option for endoscopic access to the cavity as clear advantages of SEMS compared to conventional stents[23-26]. The migration risk remains. Some interventionalists place a double pigtail stent through the metal stent to prevent stent dislocation.

Several new developments aim to simplify the EUS guided technique and to combine the steps of puncture, dilatation/enlargement of the ostium and drainage in one single tool.

The cystostome already combines the cyst puncture with an inner needle knife catheter followed by the diathermy by a metal ring at the tip of the outer sheet[27]. Exchange over a wire for stenting is still necessary. However, a new development also now comes with a preloaded straight stent which can be placed directly after diathermy.

The Giovannini stent device[28] is an all-in-one stent introduction system combining a 0.035 needle-wire suitable for cutting diathermy, a 5.5 F guiding catheter and a preloaded straight plastic stent (8, 5 or 10 F, 5-cm-long). The needle-wire is introduced under EUS-guidance into the fluid collection using cutting current. After removing the internal rigid part, the wire can be curled in the cystic cavity to stabilize the position. The guiding and dilatation catheter follows over the wire and finally the straight plastic stent can be transmurally positioned (Giovannini Needle Wire Oasis; Cook endoscopy, Winston-Salem, NC, United States). This one-step EUS-guided technique for transmural cyst access has proven safe and effective for the management of pancreatic pseudocysts and abscesses[29].

A new combination tool is the “Naxix-access-device” (Xlumena™) which consists of a 19 G trocar with a short extandable side blade. The side blade enlarges the ostium to 3.5 mm diameter which allows to advance a pear shaped anquoring and a 10 mm dilatation balloon. The device has also additional channels for guide wires and contrast injection[30]. Avoiding device exchanges, this accessory allows access, guidewire insertion, tract enlargement and dilatation.

The recent technical developments have provided us with easier deployable stent systems for the EUS-guided management of pancreatic fluid collections. The SEMS appear safer and more effective in hitherto existing case series and studies. Large-sized, randomised comparative studies are required for further evaluation and this will lead to continued improvement of the techniques.

P- Reviewer: Berg T, Mentes O, Takahashi T S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ross A, Gluck M, Irani S, Hauptmann E, Fotoohi M, Siegal J, Robinson D, Crane R, Kozarek R. Combined endoscopic and percutaneous drainage of organized pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:79-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ross AS, Irani S, Gan SI, Rocha F, Siegal J, Fotoohi M, Hauptmann E, Robinson D, Crane R, Kozarek R. Dual-modality drainage of infected and symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis: long-term clinical outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:929-935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Runzi M, Niebel W, Goebell H, Gerken G, Layer P. Severe acute pancreatitis: nonsurgical treatment of infected necroses. Pancreas. 2005;30:195-199. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sivasankar A, Kannan DG, Ravichandran P, Jeswanth S, Balachandar TG, Surendran R. Outcome of severe acute pancreatitis: is there a role for conservative management of infected pancreatic necrosis? Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5:599-604. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Garg PK, Sharma M, Madan K, Sahni P, Banerjee D, Goyal R. Primary conservative treatment results in mortality comparable to surgery in patients with infected pancreatic necrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:1089-1094.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Tamhane A, Drelichman ER, Wilcox CM. Prospective randomized trial comparing EUS and EGD for transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1102-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Park DH, Lee SS, Moon SH, Choi SY, Jung SW, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided versus conventional transmural drainage for pancreatic pseudocysts: a prospective randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2009;41:842-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dietrich CF, Hocke M, Jenssen C. [Interventional endosonography]. Ultraschall Med. 2011;32:8-22, quiz 23-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Giovannini M. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided pancreatic drainage. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2012;22:221-230, viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fabbri C, Luigiano C, Maimone A, Polifemo AM, Tarantino I, Cennamo V. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:479-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Varadarajulu S, Phadnis MA, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Multiple transluminal gateway technique for EUS-guided drainage of symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:74-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Piscaglia F, Nolsøe C, Dietrich CF, Cosgrove DO, Gilja OH, Bachmann Nielsen M, Albrecht T, Barozzi L, Bertolotto M, Catalano O. The EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations on the Clinical Practice of Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS): update 2011 on non-hepatic applications. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33:33-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 680] [Article Influence: 52.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Beyer-Enke SA, Hocke M, Ignee A, Braden B, Dietrich CF. Contrast enhanced transabdominal ultrasound in the characterisation of pancreatic lesions with cystic appearance. JOP. 2010;11:427-433. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Seifert H, Wehrmann T, Schmitt T, Zeuzem S, Caspary WF. Retroperitoneal endoscopic debridement for infected peripancreatic necrosis. Lancet. 2000;356:653-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, van Brunschot S, Geskus RB, Besselink MG, Bollen TL, van Eijck CH, Fockens P, Hazebroek EJ, Nijmeijer RM. Endoscopic transgastric vs surgical necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 498] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | van Brunschot S, Fockens P, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Voermans RP, Poley JW, Gooszen HG, Bruno M, van Santvoort HC. Endoscopic transluminal necrosectomy in necrotising pancreatitis: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1425-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Voermans RP, Ponchon T, Schumacher B, Fumex F, Bergman JJ, Larghi A, Neuhaus H, Costamagna G, Fockens P. Forward-viewing versus oblique-viewing echoendoscopes in transluminal drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1285-1293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Larghi A, Fuccio L, Attili F, Rossi ED, Napoleone M, Galasso D, Fadda G, Costamagna G. Performance of the forward-viewing linear echoendoscope for fine-needle aspiration of solid and cystic lesions throughout the gastrointestinal tract: a large single-center experience. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1801-1807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Iwashita T, Nakai Y, Lee JG, Park do H, Muthusamy VR, Chang KJ. Newly-developed, forward-viewing echoendoscope: a comparative pilot study to the standard echoendoscope in the imaging of abdominal organs and feasibility of endoscopic ultrasound-guided interventions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:362-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Binmoeller KF, Shah J. A novel lumen-apposing stent for transluminal drainage of nonadherent extraintestinal fluid collections. Endoscopy. 2011;43:337-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gornals JB, De la Serna-Higuera C, Sánchez-Yague A, Loras C, Sánchez-Cantos AM, Pérez-Miranda M. Endosonography-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections with a novel lumen-apposing stent. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1428-1434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Penn DE, Draganov PV, Wagh MS, Forsmark CE, Gupte AR, Chauhan SS. Prospective evaluation of the use of fully covered self-expanding metal stents for EUS-guided transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:679-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Berzosa M, Maheshwari S, Patel KK, Shaib YH. Single-step endoscopic ultrasonography-guided drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections with a single self-expandable metal stent and standard linear echoendoscope. Endoscopy. 2012;44:543-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Itoi T, Binmoeller KF, Shah J, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N. Clinical evaluation of a novel lumen-apposing metal stent for endosonography-guided pancreatic pseudocyst and gallbladder drainage (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:870-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Itoi T, Nageshwar Reddy D, Yasuda I. New fully-covered self-expandable metal stent for endoscopic ultrasonography-guided intervention in infectious walled-off pancreatic necrosis (with video). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:403-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mangiavillano B, Arcidiacono PG, Masci E, Mariani A, Petrone MC, Carrara S, Testoni S, Testoni PA. Single-step versus two-step endo-ultrasonography-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:47-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Giovannini M, Bernardini D, Seitz JF. Cystogastrotomy entirely performed under endosonography guidance for pancreatic pseudocyst: results in six patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:200-203. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Krüger M, Schneider AS, Manns MP, Meier PN. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts or abscesses after an EUS-guided 1-step procedure for initial access. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:409-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Binmoeller KF, Weilert F, Shah JN, Bhat YM, Kane S. Endosonography-guided transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts using an exchange-free access device: initial clinical experience. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1835-1839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |