Published online Nov 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i41.15144

Revised: March 6, 2014

Accepted: June 26, 2014

Published online: November 7, 2014

Processing time: 368 Days and 2.2 Hours

Up to 18% of patients submitted to cholecystectomy had concomitant common bile duct stones. To avoid serious complications, these stones should be removed. There is no consensus about the ideal management strategy for such patients. Traditionally, open surgery was offered but with the advent of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) minimally invasive approach had nearly replaced laparotomy because of its well-known advantages. Minimally invasive approach could be done in either two-session (preoperative ERCP followed by LC or LC followed by postoperative ERCP) or single-session (laparoscopic common bile duct exploration or LC with intraoperative ERCP). Most recent studies have found that both options are equivalent regarding safety and efficacy but the single-session approach is associated with shorter hospital stay, fewer procedures per patient, and less cost. Consequently, single-session option should be offered to patients with cholecysto-choledocholithiaisis provided that local resources and expertise do exist. However, the management strategy should be tailored according to many variables, such as available resources, experience, patient characteristics, clinical presentations, and surgical pathology.

Core tip: This paper discusses minimally invasive options for management of patients with concomitant gallbladder stones and common bile duct stones with special focus on the technique, benefits, controversial issues, and difficulties of single session approach. Additionally, we investigate recent comparative studies between single-session and two-session approach.

- Citation: ElGeidie AA. Single-session minimally invasive management of common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(41): 15144-15152

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i41/15144.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i41.15144

Between 10% to 18% of people undergoing cholecystectomy for gallstones have common bile duct (CBD) stones[1,2]. The natural history of CBD stones is not well known but it was found that up to one third of patients with CBD stones identified by intraoperative cholangiogram at the time of cholecystectomy pass their stones spontaneously within 6 wk of surgery[3]. However complications of CBD stones, including pain, partial or complete biliary obstruction, cholangitis, hepatic abscesses or pancreatitis are unpredictable, well recognized, and often serious. Therefore, it is generally recommended to treat CBD stones whenever detected even when asymptomatic[1,4].

For many years, open cholecystectomy with CBD exploration was the gold standard to treat both pathologies. In spite of the fact that open cholecystectomy with CBD exploration had the lowest incidence of retained stones there was a considerable morbidity (11%-14%) and even mortality (0.6%-1%) particularly in elderly patients[5]. In the past few decades two revolutions paved the way for the introduction of minimally invasive techniques in management of such patients; these are the development of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and LC. ERCP has become a widely available and routine procedure, whilst open cholecystectomy has largely been replaced by a laparoscopic approach, which is considered the treatment of choice for gallbladder removal since NIH Consensus on 1993[6].

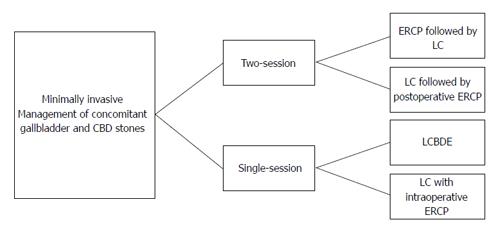

In modern surgical practice, surgeons have a number of potentially valid options for managing patients with cholecysto-choledocholithiasis with no consensus regarding the ideal one. Due to its well know advantages (less wound complications, less abdominal adhesions, faster recovery with rapid return to work, less postoperative pain and need for analgesia, less wound complications, and better cosmetic outcome), minimally invasive approach had almost replaced open surgery for management of patients with cholecysto-choledocholithiasis. In general, minimally invasive approaches to management of preoperatively suspected cholecysto-choledocholithiasis may be either two-session or single-session (Figure 1).

Preoperative ERCP followed by LC is the most commonly used treatment policy worldwide[7]. Most studies have showed that this two-session strategy is efficient and safe[8-10]. However, this approach has many drawbacks; (1) high negative results (40%-70%) exposing patients to unnecessary risky endoscopic intervention[11-13]. New imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) offer the opportunity to accurately visualize the biliary system without instrumentation of the ducts increasing the sensitivity and specificity of preoperative detection of CBD stones[14,15] but CBD stones may spontaneously pass before ERCP. Lefemine et al[16] demonstrated that more than 50% of patients with CBD stones have spontaneous passage of the stones; (2) during LC, 12.9% of patients who had preoperative endoscopic clearance of CBD still had CBD stones[17]. These stones may be either retained stones (due to false-negative ERCP or incomplete stone extraction) or new stones (due to passage of stones from gallbladder into CBD during the interval before LC); (3) previous ERCP may have adverse effects on the course of following surgery in the form of more conversion to open cholecystectomy, longer operating time, higher morbidity, especially postoperative infection, and longer hospital stay[18-20]; (4) this option needs two anesthesia and sometimes two hospital admissions, which definitely increase the hospital stay and cost; and (5) when there is time delay between preoperative ERCP and LC, some patients may escape LC being satisfied by the results of preoperative ERCP[21-23]. In many centers, LC is scheduled within 6-8 wk after ERCP, for recovering from acute illness. But it was found that recurrent biliary events occurred more in delayed group patients than in early group (36.2% vs 2.1%)[24]. At the same time early surgery was not found to be associated with increased risk of conversion and difficulties, or prolonged hospital stay[25]. Therefore, current evidence tends to support that early LC (within the same hospital admission) is superior to the delaying surgery (6-8 wk afterward).

The second minimally invasive option is LC followed later on by postoperative ERCP. Generally, postoperative ERCP is not considered as first-line treatment option for CBD stones. This is because failed postoperative ERCP, which may occur in 3%-10% of patients depending on endoscopist experience, means reoperation. Therefore, it is usually indicated when intraoperative laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) failed or for accidentally discovered stones during LC with no facilities for LCBDE or intraoperative ERCP[26,27].

The logical extension of LC was the introduction of LCBDE for suspected or proven CBD stones. LC and exploration of the CBD as a single procedure has proven to be efficient, safe, cost effective, and well accepted by patients as the two different pathologic conditions are solved in a single surgical procedure[28,29]. LCBDE is associated with successful stone clearance rates ranging from 94% to 98%, a morbidity rate of 8.8%-19% and a mortality rate of 0%[30,31]. Tai et al[32] reported that the clearance rate was 100%, and no recurrence was discovered during a mean follow-up period of 16 mo. More importantly, LCBDE avoids the adverse effects of endoscopic sphincterotomy which may be short-term (pancreatitis, bleeding and perforation), medium-term (cholangitis and recurrent stone formation), or long-term (bile duct malignancy). However, LCBDE is not devoid of drawbacks. It needs experience and specialized instruments which may not be widely available. It is also time consuming, particularly for large or impacted stones and it requires a longer learning curve because of the skill required for laparoscopic suturing in case of T-tube placement[33].

LCBDE could be performed via either the cystic duct (transcystic approach) or directly through the CBD (choledochotomy approach). The transcystic approach is favored by most biliary surgeons because of its less invasiveness but laparoscopic choledochotomy is generally indicated in patients with a wide CBD (> 9 mm in diameter) to avoid bile duct stricture[34-36], large (> 10 mm) stones, or multiple, impacted, and intrahepatic stones[37,38], and also in cases of unfavorable cystic duct anatomy (e.g., too small, tortuous cystic duct, low cystic-CBD junction) or when the transcystic approach has failed[39,40].

There are two guiding methods for removal of stones at LCBDE, which are either fluoroscopic or choledochoscopic guidance. Most surgeons prefer the use of flexible choledochoscopy at LCBDE due to the greatest sense of safety and accuracy by capturing stones under direct vision and at the same time avoiding some of the disadvantages encountered with fluoroscopic guidance (radiation exposure, time consumed and the presence of C-arm which may hamper the movement of instruments). However, flexible choledochoscope, particularly 3-mm one, is a fragile and delicate instrument that could be broken easily. Moreover, for better use of choledochoscopy simultaneous projection of laparoscopic and choledochoscopic images is needed. This usually requires a second camera, a second monitor and a video switcher which definitely increase the cost. Our search in literature yielded only one prospective nonrandomized study comparing the use of flexible choledochoscopy (in 79 patients) and fluoroscopy (in 34 patients) for LCBDE[41]. The success rate and the reported complication were not significantly different between the two groups. The only significant difference was in the surgical time which was shorter for flexible choledochoscopy group (107.5 min for fluoroscopically-guided group vs 75 min for the choledochoscopy-guided group with P value < 0.0001). We conducted a study (not published yet but under current revision) on 203 patients with concomitant gallbladder stones and CBD stones. The guiding technique for CBD stone retrieval was fluoroscopy. Compared to published studies that used choledochoscope at LCBDE[42-45], we found similar success rate (91.4%), morbidity and mortality, operative time and length of hospital stay. The complications rate in our series (4.9%) compare favorably with those reported in the literature[43,46-48].

Traditionally, the CBD is closed with T-tube drainage after choledochotomy and removal of CBD stones. This is because instrumentation of the CBD and maneuvers for stone extraction may cause edema to the papilla, leading to an increase in pressure inside the biliary tree. The advocates of the use of a T-tube argue that it allows spasm or edema of sphincter to settle after the trauma of the exploration[49,50]. A T-tube has also provided an easy percutaneous access for cholangiography and extraction of retained stones[51]. Despite these potential advantages, morbidity rates related to T-tube presence have been reported to be at a rate of 4%-16.4% in the laparoscopic era[44,52]. The T-tube-related complications include accidental T-tube displacement leading to CBD obstruction[53], bile leakage[54], persistent biliary fistulas and excoriation of the skin[55], cholangitis from exogenous sources through the T-tube, and dehydration and saline depletion[56]. Additionally, CBD stenosis has been reported as a long-term complication after T-tube removal. After discharge, indwelling T-tubes become uncomfortable, requiring continuous management, thus restricting patient activity because of the risk of dislodgement[57]. For the above-mentioned disadvantages of T-tube use, a second option for choledochotomy closure, which is primary closure of choledochotomy with placement of biliary endoprosthesis, was proposed[58,59]. Biliary endoprosthesis, as with a T-tube, achieves biliary decompression, and published results have suggested that this leads to lower morbidity, shorter postoperative hospital stay, less postoperative discomfort, and earlier return to full activities, compared to T-tube placement[60,61]. Moreover, the presence of the endoprosthesis in the duodenal lumen makes postoperative ERCP easier, in the presence of residual CBD stones[40,57]. However, the use of biliary endoprosthesis is not devoid of complications such as duodenal erosion[62], stent occlusion[63], ampullary stenosis[64], and distant stent migration, causing intestinal[65] or colonic perforation[66]. Moreover, removal of biliary endoprosthesis requires second-session endoscopic extraction.

A third option for choledochotomy closure is primary closure without the use of T-tube or biliary endoprosthesis. In a prospective randomized trial, El-Geidie[67] compared the use of T-tube and primary closure after laparoscopic choledochotomy in 122 consecutive patients and found that the operative time and postoperative stay were significantly shorter and the incidence of complications was statistically and significantly lower in the primary closure group. Gurusamy et al[68] in a meta-analysis which included three trials with 295 patients randomized (147 to T-tube and 148 to primary closure) found that there was no mortality in either group. There was no significant difference in the serious morbidity rates (17/147 in T-tube group versus 9/148 in primary closure group). The operating time was significantly longer in the T-tube group than primary closure group. The hospital stay was also significantly longer in the T-tube group than the primary closure group. The patients in the T-tube drainage group returned to work significantly later (approximately 8 d later) than the primary closure group (P < 0.005). They concluded that there is no justification for the routine use of T-tube drain compared with primary closure after laparoscopic CBD exploration. T-tube drainage results in significantly longer operating time and hospital stay as compared to primary closure.

Another method of single-session minimally invasive treatment of cholecysto-choledocholithiasis has been described; that is the use of intraoperative ERCP to extract CBD stones, identified by intraoperative cholangiography in patients who are undergoing LC[69-72]. This option was found by many experts to be safe, effective, and less expensive single-session management[11,32,69,70,72-75]. Table 1 shows the theoretical benefits of this approach. In spite of its benefits, intraoperative ERCP had not gained widespread acceptance. This is mostly because the availability of intra-operative ERCP in many centers is limited, and the requirement to have an endoscopist experienced in ERCP available for all cases would be prohibitive, unless the surgeon had this skill, this would mean a limited applicability.

| Single hospital stay with single anesthesia |

| CBD stones may be removed without open CBD exploration when LCBDE is not feasible |

| The patient is not subjected to the possibility of failure of postoperative ERCP |

| If intraoperative ERCP is unsuccessful, then open/laparoscopic CBD exploration is performed under the same anesthetic |

| Endoscopic sphincterotomy performed during intraoperative ERCP facilitates postoperative ERCP if needed for removal of recurrent or residual CBD stones |

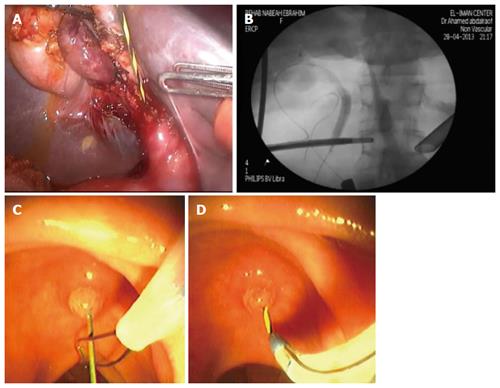

There are many described techniques for performing IO-ERCP during LC. The first described one was standard ERCP during LC. During LC, catheterization of the cystic duct and intraoperative cholangiography is performed. If intraoperative cholangiogram yielded positive result, intraoperative ERCP is performed in the operating room. After verification of clearance of CBD, LC was continued[73,76]. A variation of this technique is postponing ERCP till after completion of LC and closure of the ports. This is to avoid the problems of supine position (making papillary cannulation somewhat difficult) and bowel distension (making LC more demanding)[77]. Another technique of intraoperative ERCP, which differs from standard one, had been described by Cavina et al[71] to facilitate cannulation with the patient in supine position. This is called the combined laparo-endoscopic or “Rendez-vous (RV)” procedure. A dormia basket is passed into the duodenum through the cystic duct; with a RV procedure, it retrieves the sphincterotome from the duodenoscope and guided it into the bile duct. A slightly modified RV technique was described by other investigators and became more commonly practiced due to its simplicity[12,69,70]. A guidewire is introduced through the intraoperative cholangiography catheter into the cystic duct and out the ampulla of Vater into the duodenum. Using side-viewing duodenoscope the protruding guidewire is grasped by a snare or basket and a standard sphincterotome is threaded over it to facilitate endoscopic sphincterotomy and/or stone removal (Figure 2). DePaula et al[78] have devised a technique that combines intraoperative cholangiography with ES. This variation again involves laparoscopic passage of a wire through the cystic duct and out the ampulla into the duodenum. An endoscopic sphincterotome is passed over the wire anterograde through the papilla. An ES is then performed under the direct vision of a simultaneously positioned duodenoscope. Stones can then be pushed or pulled out of the CBD. Curet et al[79] also reported the use of antegrade technique in the management of multiple CBD stones and 6 patients were successfully treated. In one nonrandomized comparative study comparing the combined rendezvous procedure and antegrade technique, duct stones clearance and morbidity are equivalent in these 2 groups, whereas the group of rendezvous procedure had a longer operative time of 117 min due partly to more maneuvers and decreased working space related to bowel distension[80].

Ponsky et al[81] also described the use of a laparoscopically placed wire that is passed through the cystic duct and transverses the ampulla. An endoscopic biliary stent is passed over this wire laparoscopically. The stent serves to drain the CBD and facilitates a precut ES, ensuring the success of postoperative ERCP and removal of any retained stones. Fitzgibbons et al[82] treated 52 patients with guidewire assisted endoscopic retrograde spincterotomy. Percutaneous double-lumen catheters were placed through the cystic duct into the duodenum at LC. Repeat cholangiograms through the catheter was done at 10-14 d. Patients who had negative studies saved any further unnecessary procedures whereas patients with positive findings on cholangiography underwent ERCP using a guidewire placed through the catheter.

Beside higher success rate of cannulation with the patient in supine position, the postprocedural hyperamylasemia and acute pancreatitis are strongly reduced or absent after RV if compared with standard ERCP[70,83,84]. This is because inadvertent pancreatic duct injection and cannulation at standard ERCP, which is the most important risk factor for the development of post-ERCP pancreatitis, is avoided in the RV technique[12,85-87].

RV technique has the problem of failure of passage of the guidewire through the spiral valves of the cystic duct. The cystic duct may be torn during manipulations adding more difficulties. The guidewire, even inside the CBD, may fail to pass across the sphincter in the presence of impacted stones. Another technical problem that could be encountered with RV technique is bowel distention induced by endoscopic insufflation that can decrease the working space for cholecystectomy. Several technical solutions have been proposed to overcome the problem, including the use of an atraumatic laparoscopic clamp positioned on the first jejunal loop[83] and a bowel desufflator[87]. Another way of minimizing the difficulty of LC is to completely dissect the Calot triangle and the attachment between liver and gallbladder or even remove the gallbladder from the liver bed until the last centimeters is left at the fundus before the starting of endoscopic phase[83,88].

El-Geidie[77] compared the two techniques of intraoperative ERCP (standard vs RV) in a prospective randomized study including 98 patients with gallbladder stones and CBDS and we found no differences in success/failure rate or post-ERCP pancreatitis. There was a significant difference in operative time which was shorter for standard ERCP. This operative time difference is due to difficulties at cholecystectomy related to bowel distension. Another important factor is the time wasted till arrival of endoscopy in case of accidentally discovered CBD stones.

The first trial to compare the two approaches was the EAES ductal stone trial[28]. The study consists of a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial included 207 patients and compared preoperative ERCP followed by LC and LCBDE in patients undergoing LC and suspected of harboring CBD stones. The findings indicated equivalent success rates and patient morbidity between the two management options but a shorter hospital stay (cost benefit) with the single session laparoscopic treatment.

A recent prospective randomized trial compared the success and cost effectiveness of single- and two-session management of patients with concomitant gallbladder and CBD stones[9]. 168 patients were randomized: 84 to the single-session procedure (LCBDE) and 84 to the two-session procedure (preoperative ERCP followed by LC). The success rates of LCBDE and ERCP for clearance of CBD were similar (91.7% vs 88.1%). The mean operative time was significantly longer in LCBDE group, but the overall hospital stay was significantly shorter. ERCP group had a significantly greater number of procedures per patient (P < 0.001) and a higher cost (P = 0.002). The two groups did not differ significantly in terms of postoperative wound infection rates or major complications. Authors concluded that single- and two-session management for uncomplicated concomitant gallbladder and CBD stones had similar success and complication rates, but the single-session strategy was better in terms of shorter hospital stay, need for fewer procedures, and cost effectiveness.

In 2011, Li et al[10] carried a meta-analysis on eleven randomized comparative trials (RCTs); five randomized comparative trials comparing preoperative ERCP and LC to LCBDE, two RCTs comparing LCBDE to LC and postoperative ERCP, three RCTs comparing preoperative ERCP and LC against LC with intraoperative ERCP, and one RCT comparing preoperative ERCP and LC against LC and postoperative ERCP. They concluded that different management approaches of concomitant gallbladder stones and CBD stones were equivalent in efficacy. However, one-session management had the advantage of providing a shorter hospital stay.

In a meta-analysis comparing one-session (LCBDE or intraoperative ERCP) vs two-session (LC preceded or followed by ERCP) management of CBD stones, nine randomized trials with 933 patients were studied[89]. Outcomes after one-session laparoscopic/endoscopic management of bile duct stones were not different to the outcomes after two-session management with no significant differences between the two groups with regard to bile duct clearance, total morbidity, major morbidity and the need for additional procedures.

Lu et al[90] evaluated the safety and effectiveness of two-session vs single-session management for concomitant gallstones and common bile duct stones in a meta-analysis. Seven eligible RCTs [five trials (n = 621) comparing preoperative (ERCP + LC) with (LC + LCBDE); two trials (n = 166) comparing postoperative (ERCP + LC) with (LC + LCBDE), composed of 787 patients in total, were included. The meta-analysis detected no statistically significant difference between the two groups in stone clearance, postoperative morbidity, mortality, conversion to other procedures, length of hospital stay, total operative time. Two-session (LC + ERCP) management clearly required more procedures per patient than single-session (LC + LCBDE) management.

In a recent systematic review, Dasari et al[91] reviewed the benefits and harms of different approaches to the management of common bile duct stones and they found that there is no significant difference in the mortality and morbidity between laparoscopic bile duct clearance and the endoscopic options. There is no significant reduction in the number of retained stones and failure rates in the laparoscopy groups compared with the pre-operative and intra-operative ERCP groups. There is no significant difference in the mortality, morbidity, retained stones, and failure rates between the single-session laparoscopic bile duct clearance and two-session endoscopic management. More randomized clinical trials without risks of systematic and random errors are necessary to confirm these findings.

Hong et al[92] compared laparoscopic cholecystectomy combined with intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy with laparoscopic CBD exploration. For this study, 234 patients with cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis diagnosed by preoperative B-ultrasonography and intraoperative cholangiogram were divided at random into LC-LCBDE group (141cases) and LC with intraoperative ERCP group (93 cases). There was no difference between the two groups in terms of surgical time, surgical success rate, number of stone extractions, postoperative complications, retained common bile duct stones, postoperative length of stay, and hospital charge. It was concluded that both approaches were shown to be safe, effective, minimally invasive treatments for concomitant gallbladder and CBD stones.

ElGeidie et al[93] compared these two procedures in 211 patients (110 LCBDE vs 101 intraoperative ERCP) and found nearly similar results. The diagnosis was based on preoperative MRCP. It was found that there were no significant differences between LCBDE and intraoperative ERCP in terms of success/failure rate, surgical time, and postoperative length of stay. The complication rates were also comparable. The only significant difference was in the rate of retained stones which was more in LCBDE group.

Single-session approach (in the form of LCBDE or intraoperative ERCP) for managing patients with concomitant gallbladder stones and CBD stones is equally effective and safe to the commonly practiced two-session approach but at the same time is associated with shorter hospital stay, fewer procedures and less cost. Consequently, when local resources and expertise are available it should be offered to fit patients. However, there are several factors that can affect the choice of the technique including the patient fitness, the clinical presentation, the timing of CBD stones diagnosis (established pre-operative diagnosis or incidental intraoperative diagnosis), the surgical pathology and the local expertise. It is worth mentioning that some patients are not candidate for single-session option such as patients with acute biliary pancreatitis and patients with septic shock from cholangitis. Those patients need a different approach.

P- Reviewer: Campagnacci R, de Tejada AH, Kapetanos D S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Williams EJ, Green J, Beckingham I, Parks R, Martin D, Lombard M. Guidelines on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut. 2008;57:1004-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Soltan HM, Kow L, Toouli J. A simple scoring system for predicting bile duct stones in patients with cholelithiasis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;5:434-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Collins C, Maguire D, Ireland A, Fitzgerald E, O’Sullivan GC. A prospective study of common bile duct calculi in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: natural history of choledocholithiasis revisited. Ann Surg. 2004;239:28-33. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Scientific Committee of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (E. A.E.S.). Diagnosis and treatment of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Results of a consensus development conference. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:856-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Phillips EH, Toouli J, Pitt HA, Soper NJ. Treatment of common bile duct stones discovered during cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:624-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gallstones and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Gallstones and Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1993;7:271-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Freitas ML, Bell RL, Duffy AJ. Choledocholithiasis: evolving standards for diagnosis and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3162-3167. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Lu J, Xiong XZ, Cheng Y, Lin YX, Zhou RX, You Z, Wu SJ, Cheng NS. One-stage versus two-stage management for concomitant gallbladder stones and common bile duct stones in patients with obstructive jaundice. Am Surg. 2013;79:1142-1148. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Bansal VK, Misra MC, Rajan K, Kilambi R, Kumar S, Krishna A, Kumar A, Pandav CS, Subramaniam R, Arora MK. Single-stage laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and cholecystectomy versus two-stage endoscopic stone extraction followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients with concomitant gallbladder stones and common bile duct stones: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:875-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Li MK, Tang CN, Lai EC. Managing concomitant gallbladder stones and common bile duct stones in the laparoscopic era: a systematic review. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2011;4:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Erickson RA, Carlson B. The role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:252-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Enochsson L, Lindberg B, Swahn F, Arnelo U. Intraoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to remove common bile duct stones during routine laparoscopic cholecystectomy does not prolong hospitalization: a 2-year experience. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:367-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Coppola R, Riccioni ME, Ciletti S, Cosentino L, Ripetti V, Magistrelli P, Picciocchi A. Selective use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography to facilitate laparoscopic cholecystectomy without cholangiography. A review of 1139 consecutive cases. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1213-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Garrow D, Miller S, Sinha D, Conway J, Hoffman BJ, Hawes RH, Romagnuolo J. Endoscopic ultrasound: a meta-analysis of test performance in suspected biliary obstruction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:616-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kaltenthaler EC, Walters SJ, Chilcott J, Blakeborough A, Vergel YB, Thomas S. MRCP compared to diagnostic ERCP for diagnosis when biliary obstruction is suspected: a systematic review. BMC Med Imaging. 2006;6:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lefemine V, Morgan RJ. Spontaneous passage of common bile duct stones in jaundiced patients. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:209-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pierce RA, Jonnalagadda S, Spitler JA, Tessier DJ, Liaw JM, Lall SC, Melman LM, Frisella MM, Todt LM, Brunt LM. Incidence of residual choledocholithiasis detected by intraoperative cholangiography at the time of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients having undergone preoperative ERCP. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2365-2372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ishizaki Y, Miwa K, Yoshimoto J, Sugo H, Kawasaki S. Conversion of elective laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy between 1993 and 2004. Br J Surg. 2006;93:987-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | de Vries A, Donkervoort SC, van Geloven AA, Pierik EG. Conversion rate of laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in the treatment of choledocholithiasis: does the time interval matter? Surg Endosc. 2005;19:996-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ros A, Gustafsson L, Krook H, Nordgren CE, Thorell A, Wallin G, Nilsson E. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus mini-laparotomy cholecystectomy: a prospective, randomized, single-blind study. Ann Surg. 2001;234:741-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Byrne MF, McLoughlin MT, Mitchell RM, Gerke H, Pappas TN, Branch MS, Jowell PS, Baillie J. The fate of patients who undergo “preoperative” ERCP to clear known or suspected bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:74-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yi SY. Recurrence of biliary symptoms after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis in patients with gall bladder stones. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:661-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lau JY, Leow CK, Fung TM, Suen BY, Yu LM, Lai PB, Lam YH, Ng EK, Lau WY, Chung SS. Cholecystectomy or gallbladder in situ after endoscopic sphincterotomy and bile duct stone removal in Chinese patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:96-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Schiphorst AH, Besselink MG, Boerma D, Timmer R, Wiezer MJ, van Erpecum KJ, Broeders IA, van Ramshorst B. Timing of cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2046-2050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Reinders JS, Goud A, Timmer R, Kruyt PM, Witteman BJ, Smakman N, Breumelhof R, Donkervoort SC, Jansen JM, Heisterkamp J. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy improves outcomes after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledochocystolithiasis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2315-2320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rhodes M, Sussman L, Cohen L, Lewis MP. Randomised trial of laparoscopic exploration of common bile duct versus postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiography for common bile duct stones. Lancet. 1998;351:159-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 329] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Nathanson LK, O’Rourke NA, Martin IJ, Fielding GA, Cowen AE, Roberts RK, Kendall BJ, Kerlin P, Devereux BM. Postoperative ERCP versus laparoscopic choledochotomy for clearance of selected bile duct calculi: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2005;242:188-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cuschieri A, Croce E, Faggioni A, Jakimowicz J, Lacy A, Lezoche E, Morino M, Ribeiro VM, Toouli J, Visa J. EAES ductal stone study. Preliminary findings of multi-center prospective randomized trial comparing two-stage vs single-stage management. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:1130-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tranter SE, Thompson MH. Comparison of endoscopic sphincterotomy and laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1495-1504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rojas-Ortega S, Arizpe-Bravo D, Marín López ER, Cesin-Sánchez R, Roman GR, Gómez C. Transcystic common bile duct exploration in the management of patients with choledocholithiasis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:492-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Thompson MH, Tranter SE. All-comers policy for laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1608-1612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Tai CK, Tang CN, Ha JP, Chau CH, Siu WT, Li MK. Laparoscopic exploration of common bile duct in difficult choledocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:910-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Poulose BK, Speroff T, Holzman MD. Optimizing choledocholithiasis management: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Arch Surg. 2007;142:43-48; discussion 49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Martin IJ, Bailey IS, Rhodes M, O’Rourke N, Nathanson L, Fielding G. Towards T-tube free laparoscopic bile duct exploration: a methodologic evolution during 300 consecutive procedures. Ann Surg. 1998;228:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Berthou JCh, Dron B, Charbonneau P, Moussalier K, Pellissier L. Evaluation of laparoscopic treatment of common bile duct stones in a prospective series of 505 patients: indications and results. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1970-1974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 36. | Dion YM, Ratelle R, Morin J, Gravel D. Common bile duct exploration: the place of laparoscopic choledochotomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:419-424. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Ahmed S. Laparoscopic bile duct exploration (Re: ANZ J. Surg. 2010; 80: 694-8). ANZ J Surg. 2011;81:300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Memon MA, Hassaballa H, Memon MI. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: the past, the present, and the future. Am J Surg. 2000;179:309-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Decker G, Borie F, Millat B, Berthou JC, Deleuze A, Drouard F, Guillon F, Rodier JG, Fingerhut A. One hundred laparoscopic choledochotomies with primary closure of the common bile duct. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:12-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | DePaula AL, Hashiba K, Bafutto M, Machado C, Ferrari A, Machado MM. Results of the routine use of a modified endoprosthesis to drain the common bile duct after laparoscopic choledochotomy. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:933-935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Topal B, Aerts R, Penninckx F. Laparoscopic common bile duct stone clearance with flexible choledochoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2317-2321. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Tinoco R, Tinoco A, El-Kadre L, Peres L, Sueth D. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. Ann Surg. 2008;247:674-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Sandzén B, Haapamäki MM, Nilsson E, Stenlund HC, Oman M. Treatment of common bile duct stones in Sweden 1989-2006: an observational nationwide study of a paradigm shift. World J Surg. 2012;36:2146-2153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Cuschieri A, Lezoche E, Morino M, Croce E, Lacy A, Toouli J, Faggioni A, Ribeiro VM, Jakimowicz J, Visa J. E.A.E.S. multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing two-stage vs single-stage management of patients with gallstone disease and ductal calculi. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:952-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 45. | Rijna H, Borgstein PJ, Meuwissen SG, de Brauw LM, Wildenborg NP, Cuesta MA. Selective preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in laparoscopic biliary surgery. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1130-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Lezoche E, Paganini AM, Carlei F, Feliciotti F, Lomanto D, Guerrieri M. Laparoscopic treatment of gallbladder and common bile duct stones: a prospective study. World J Surg. 1996;20:535-541; discussion 542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Khoo DE, Walsh CJ, Cox MR, Murphy CA, Motson RW. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: evolution of a new technique. Br J Surg. 1996;83:341-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Millat B, Fingerhut A, Deleuze A, Briandet H, Marrel E, de Seguin C, Soulier P. Prospective evaluation in 121 consecutive unselected patients undergoing laparoscopic treatment of choledocholithiasis. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1266-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Holdsworth RJ, Sadek SA, Ambikar S, Cuschieri A. Dynamics of bile flow through the human choledochal sphincter following exploration of the common bile duct. World J Surg. 1989;13:300-304; discussion 305-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | De Roover D, Vanderveken M, Gerard Y. Choledochotomy: primary closure versus T-tube. A prospective trial. Acta Chir Belg. 1989;89:320-324. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Paganini AM, Feliciotti F, Guerrieri M, Tamburini A, De Sanctis A, Campagnacci R, Lezoche E. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2001;11:391-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Martin IJ, Lewis RJ, Bernstein MA, Beattie IG, Martin CA, Riley RJ, Springthorpe B. Which hydroxy? Evidence for species differences in the regioselectivity of glucuronidation in rat, dog, and human in vitro systems and dog in vivo. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:1502-1507. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Bernstein DE, Goldberg RI, Unger SW. Common bile duct obstruction following T-tube placement at laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:362-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Kacker LK, Mittal BR, Sikora SS, Ali W, Kapoor VK, Saxena R, Das BK, Kaushik SP. Bile leak after T-tube removal--a scintigraphic study. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:975-978. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Ortega López D, Ortiz Oshiro E, La Peña Gutierrez L, Martínez Sarmiento J, Sobrino del Riego JA, Alvarez Fernandez-Represa J. Scintigraphic detection of biliary fistula after removal of a T tube. Br J Surg. 1995;82:82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Lygidakis NJ. Choledochotomy for biliary lithiasis: T-tube drainage or primary closure. Effects on postoperative bacteremia and T-tube bile infection. Am J Surg. 1983;146:254-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Gersin KS, Fanelli RD. Laparoscopic endobiliary stenting as an adjunct to common bile duct exploration. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:301-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 58. | Wu JS, Soper NJ. Comparison of laparoscopic choledochotomy closure techniques. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1309-1313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Griniatsos J, Karvounis E, Arbuckle J, Isla AM. Cost-effective method for laparoscopic choledochotomy. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:35-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Sheen-Chen SM, Chou FF. Choledochotomy for biliary lithiasis: is routine T-tube drainage necessary? A prospective controlled trial. Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156:387-390. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Sheridan WG, Williams HO, Lewis MH. Morbidity and mortality of common bile duct exploration. Br J Surg. 1987;74:1095-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Lowe GM, Bernfield JB, Smith CS, Matalon TA. Gastric pneumatosis: sign of biliary stent-related perforation. Radiology. 1990;174:1037-1038. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Yeoh KG, Zimmerman MJ, Cunningham JT, Cotton PB. Comparative costs of metal versus plastic biliary stent strategies for malignant obstructive jaundice by decision analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:466-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Johanson JF, Schmalz MJ, Geenen JE. Incidence and risk factors for biliary and pancreatic stent migration. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:341-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Mofidi R, Ahmed K, Mofidi A, Joyce WP, Khan Z. Perforation of ileum: an unusual complication of distal biliary stent migration. Endoscopy. 2000;32:S67. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Lenzo NP, Garas G. Biliary stent migration with colonic diverticular perforation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:543-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | El-Geidie AA. Is the use of T-tube necessary after laparoscopic choledochotomy? J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:844-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Gurusamy KS, Koti R, Davidson BR. T-tube drainage versus primary closure after laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD005641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | De Palma GD, Angrisani L, Lorenzo M, Di Matteo E, Catanzano C, Persico G, Tesauro B. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC), intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES), and common bile duct stones (CBDS) extraction for management of patients with cholecystocholedocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:649-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Deslandres E, Gagner M, Pomp A, Rheault M, Leduc R, Clermont R, Gratton J, Bernard EJ. Intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:54-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Cavina E, Franceschi M, Sidoti F, Goletti O, Buccianti P, Chiarugi M. Laparo-endoscopic “rendezvous”: a new technique in the choledocholithiasis treatment. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1430-1435. [PubMed] |

| 72. | Brady PG, Pinkas H, Pencev D. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dig Dis. 1996;14:371-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Kalimi R, Cosgrove JM, Marini C, Stark B, Gecelter GR. Combined intraoperative laparoscopic cholecystectomy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: lessons from 29 cases. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:232-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Wright BE, Freeman ML, Cumming JK, Quickel RR, Mandal AK. Current management of common bile duct stones: is there a role for laparoscopic cholecystectomy and intraoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography as a single-stage procedure? Surgery. 2002;132:729-735; discussion 735-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Rogers SJ, Cello JP, Horn JK, Siperstein AE, Schecter WP, Campbell AR, Mackersie RC, Rodas A, Kreuwel HT, Harris HW. Prospective randomized trial of LC+LCBDE vs ERCP/S+LC for common bile duct stone disease. Arch Surg. 2010;145:28-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 76. | Hong DF, Li JD, Gao M. One hundred and six cases analyses of laparoscopic technique combined with intraoperative cholangiogram and endoscopic sphincterotomy in sequential treatment of cholelithiasis. Chin J Gen Surg. 2003;15:648-650. |

| 77. | El-Geidie AA. Laparoendoscopic management of concomitant gallbladder stones and common bile duct stones: what is the best technique? Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:282-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | DePaula AL, Hashiba K, Bafutto M, Zago R, Machado MM. Laparoscopic antegrade sphincterotomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1993;3:157-160. [PubMed] |

| 79. | Curet MJ, Pitcher DE, Martin DT, Zucker KA. Laparoscopic antegrade sphincterotomy. A new technique for the management of complex choledocholithiasis. Ann Surg. 1995;221:149-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Tekin A, Ogetman Z, Altunel E. Laparoendoscopic “rendezvous” versus laparoscopic antegrade sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis. Surgery. 2008;144:442-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Ponsky JL, Scheeres DE, Simon I. Endoscopic retrograde cholangioscopy. An adjunct to endoscopic exploration of the common bile duct. Am Surg. 1990;56:235-237. [PubMed] |

| 82. | Fitzgibbons RJ, Deeik RK, Martinez-Serna T. Eight years’ experience with the use of a transcystic common bile duct duodenal double-lumen catheter for the treatment of choledocholithiasis. Surgery. 1998;124:699-705; discussion 705-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Morino M, Baracchi F, Miglietta C, Furlan N, Ragona R, Garbarini A. Preoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy versus laparoendoscopic rendezvous in patients with gallbladder and bile duct stones. Ann Surg. 2006;244:889-893; discussion 893-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | La Greca G, Barbagallo F, Di Blasi M, Di Stefano M, Castello G, Gagliardo S, Latteri S, Russello D. Rendezvous technique versus endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography to treat bile duct stones reduces endoscopic time and pancreatic damage. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:167-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Rábago LR, Vicente C, Soler F, Delgado M, Moral I, Guerra I, Castro JL, Quintanilla E, Romeo J, Llorente R. Two-stage treatment with preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) compared with single-stage treatment with intraoperative ERCP for patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis with possible choledocholithiasis. Endoscopy. 2006;38:779-786. [PubMed] |

| 86. | Ghazal AH, Sorour MA, El-Riwini M, El-Bahrawy H. Single-step treatment of gall bladder and bile duct stones: a combined endoscopic-laparoscopic technique. Int J Surg. 2009;7:338-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Lella F, Bagnolo F, Rebuffat C, Scalambra M, Bonassi U, Colombo E. Use of the laparoscopic-endoscopic approach, the so-called “rendezvous” technique, in cholecystocholedocholithiasis: a valid method in cases with patient-related risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:419-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Gagner M. Intra-operative sphincterotomy and ERCP for choledocholithiasis during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery. 2010;147:463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Alexakis N, Connor S. Meta-analysis of one- vs. two-stage laparoscopic/endoscopic management of common bile duct stones. HPB (Oxford). 2012;14:254-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Lu J, Cheng Y, Xiong XZ, Lin YX, Wu SJ, Cheng NS. Two-stage vs single-stage management for concomitant gallstones and common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3156-3166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Dasari BV, Tan CJ, Gurusamy KS, Martin DJ, Kirk G, McKie L, Diamond T, Taylor MA. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD003327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Hong DF, Xin Y, Chen DW. Comparison of laparoscopic cholecystectomy combined with intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy and laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct for cholecystocholedocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:424-427. [PubMed] |

| 93. | ElGeidie AA, ElShobary MM, Naeem YM. Laparoscopic exploration versus intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones: a prospective randomized trial. Dig Surg. 2011;28:424-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |