Published online Aug 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i29.10144

Revised: February 11, 2014

Accepted: February 17, 2014

Published online: August 7, 2014

Processing time: 327 Days and 13.6 Hours

AIM: To provide trends in incidence, management and survival of cancer of the ampulla of Vater in a well-defined French population.

METHODS: Data were obtained from the population-based digestive cancer registry of Burgundy over a 34-year period. Age-standardized incidence rates were computed using the world standard population. Average annual variations in incidence rates were estimated using a poisson regression. A univariate and multivariate relative survival analysis was performed.

RESULTS: Age-standardized incidence rates were 0.46 and 0.30 per 100000 inhabitants for men and women, respectively. Incidence rate increased from 0.26 (1976-1984) to 0.58 (2003-2009) for men and remained stable for women. Resection for cure was performed in 48.3% of cases. This proportion was stable over the study period. Among cases with curative resection, pancreatico-duodenectomy was performed in 94.0% of cases and ampullectomy in 6.0% of cases. A total of 50.8% of cancers of the ampulla of Vater were diagnosed at an advanced stage. Their proportion remained stable throughout the study period. The overall 1- and 5-year relative survival rates were 60.2% and 27.7%, respectively. Relative survival did not vary over time. Treatment and stage at diagnosis were the most important determinants of survival. The 5-year relative survival rate was 41.5% after resection for cure, 9.5% after palliative surgery and 6.7% after symptomatic treatment. In multivariate analysis, only stage at diagnosis significantly influenced the risk of death.

CONCLUSION: Cancer of the ampulla of Vater is still uncommon, but its incidence increased for men in Burgundy. Diagnosis is often made at an advanced stage, dramatically worsening the prognosis.

Core tip: Cancer of the ampulla of Vater is still uncommon, but its incidence increased for men in Burgundy. Cancers were diagnosed at an advanced stage (distant metastasis and/or unresectable) in 50.8% of the cases. Resection for cure was performed in half of patients. The absence of improvement in stage at diagnosis and overall survival over time is disappointing. The overall 5-year relative survival rate was 27.7%, and did not vary over time. The 5-year relative survival rate was 41.5% after resection for cure, 9.5% after palliative surgery and 6.7% after symptomatic treatment. In multivariate analysis, only stage at diagnosis significantly influenced the risk of death.

- Citation: Rostain F, Hamza S, Drouillard A, Faivre J, Bouvier AM, Lepage C. Trends in incidence and management of cancer of the ampulla of Vater. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(29): 10144-10150

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i29/10144.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i29.10144

The epidemiological characteristics of cancer of the ampulla of Vater are not well known. This may be due to the fact that it is rare and that most epidemiological studies have considered cancers of the ampulla of Vater, extra-hepatic bile duct cancers and sometimes gallbladder cancers as a single entity[1,2]. However, interest in this disease is rising due to the introduction of new surgical and endoscopic procedures[3-7]. Most of the available data is provided by specialised centres and thus cannot be used as a reference because of unavoidable selection bias. Population-based studies using data from registries, which record all cases in a well-defined population, are the best way to assess the epidemiological characteristics, management and real prognosis. Such studies are rare, however, because they require accurate and detailed data, which are seldom collected systematically by cancer registries. The objective of this study was to describe time trends in the incidence, treatment, stage at diagnosis, and prognosis of cancer of the ampulla of Vater in a well-defined French population over a 34-year period.

A population-based cancer registry records all digestive tract cancers in two administrative areas in Burgundy (France): Côte d’Or and Saône-et-Loire (1078864 inhabitants according to the 2009 census). Information was collected from public and private pathology laboratories, university hospitals and general hospitals, private hospital surgeons, gastroenterologists, medical oncologists, radiotherapists, the administrative hospital data base, the Regional Health service data base and death certificates. Since the latter are somewhat unreliable, no case was recorded through death certificates alone, but these are used to identify missing cases. The quality and completeness of the registry is certified every 4 years through an audit carried out by the National Institute for Health and Medical Research (INSERM) and the National Public Health Institute (InVS). Given the multiple sources of information we assumed that nearly all newly diagnosed cases were recorded. A total of 256 patients with cancer of the ampulla of Vater were recorded in the registry between 1976 and 2009.

For each case of cancer of the ampulla of Vater, sex, age, year at diagnosis, histological type[8], treatment and stage at diagnosis were recorded. Surgical procedures were divided into different modalities: resection for cure R0 (macroscopic resection of all malignant tissue and no microscopic evidence of surgical margin spread), palliative surgery (including palliative resection, by-pass, local laser application, and exploratory laparotomy), and symptomatic treatment when there was no carcinologic intent. Treatment modalities were known for all cases. Operative mortality was defined as death within 30 d of surgery. Using all available information, in particular pathological records, the stage at diagnosis was coded according to the 2009 version of the AJCC classification[9]. Four stages were identified. Stage I: limited to the ampulla of Vater or invading the duodenal wall (T1/2N0M0). Stage II: spread to the pancreas with negative nodes (T3N0M0) or regional lymph node metastasis without distant metastasis (T1/2/3N1M0). Stage III: tumour invading peripancreatic soft tissues or other adjacent organs (colon, stomach, abdominal wall or portal vein and hepatic artery) without distant metastasis (T4anyNM0). Stage IV: tumour with distant metastasis (anyTanyNM1). Non-resected cancers without distant metastasis were also classified as TNM stage IV and both were defined as advanced stage.

The thirty four years of the study were divided into four periods: three 9-year periods and one 7-year period (1976-1984, 1985-1993, 1994-2002, and 2003-2009). Data on vital status were provided by death certificates, the National Repertory of National Person Identification, registrars of the place of birth or from practitioners. Life status was known for 239 cases (93.4%) at 31st December 2011.

The populations used in calculating incidence rates were based on annual estimates of the covered population. Incidence rates were age-standardised according to the world standard population and are given per 100000 inhabitants. Average annual variations in incidence rates were estimated using a Poisson regression, adjusted for age for each gender. Associations between categorical data were analysed using the χ2 test for homogeneity.

Relative survival rates, defined as the ratio of the observed survival rate in the cancer patients under study, to the expected survival rate in a population with similar sex and age distribution derived from local mortality tables, were calculated. They reflect the excess mortality in the cancer patient group relative to background mortality. A multivariate survival analysis was performed using a relative survival model with proportional hazards applied to the net survival by intervals[10]. The significance of the covariates was tested using the likelihood ratio test. Time trends were computed using STATA, release 11 (STATA corp., College Station, Texas).

A total of 256 cancers of the ampulla of Vater were recorded. They accounted for 0.6% of the digestive cancers recorded in men and 0.8% of those recorded in women. The crude annual incidence rate was 0.83 per 100000 inhabitants in men and 0.75 per 100000 inhabitants in women. The corresponding age-standardised rates were respectively 0.46 and 0.30 per 100000 inhabitants. The sex ratio calculated on the age-standardised incidence rate was 1.5.

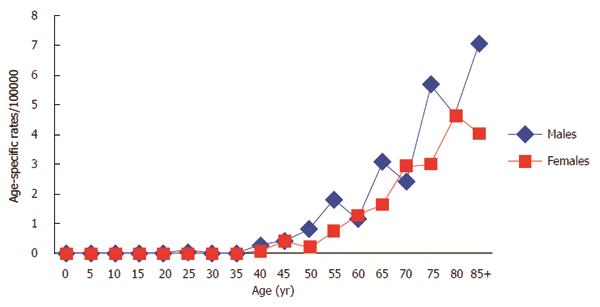

All cases but one was diagnosed after age 40 years. Age-specific incidence rates were slightly higher in men than in women (Figure 1). The mean age at diagnosis was 69.5 years (SD: 12.5 years) for men and 74.0 years (SD: 11.5 years) for women (P = 0.0034).

Age at diagnosis did not significantly change over the four periods of the study. However, we noted an increasing trend over time in the proportion of patients of 75 years and over: 40% between 1976 and 1984, and 58% between 2003 and 2009. The proportion of histologically verified cases was 82.8%. There was no significant change over the study periods. Among the 212 histologically proven cases there were 205 adenocarcinomas and 7 neuroendocrine tumours. The diagnosis was based on morphologic examinations in 44 cases.

The incidence of cancer of the ampulla of Vater showed a substantial increase in men over the study period. Age standardised incidence rates were respectively 0.26, 0.39, 0.52 and 0.58 per 100000 inhabitants for the four study periods in men. In women, the incidence rates were respectively 0.23, 0.40, 0.30 and 0.25 per 100000. The mean annual percentage of variation was 4.6% for men (95%CI: 2.4-6.7, P < 0.001). There was no significant variation in women.

There has been no major variation in the surgical treatment of cancers of the ampulla of Vater. The proportion of resection for cure did not vary significantly over time (Table 1). Between 1976 and 1984, R0 resection was performed in 40.0% of cases. This increased to 51.5% during the period 1985-1993, after which it remained stable. Perioperative mortality was 8.6% over the study period.

| 1976-1984(n = 25) | 1985-1993(n = 67) | 1994-2002(n = 82) | 2003-2009(n = 81) | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Resection for cure | 40.0% | 51.5% | 48.8% | 49.4% |

| Palliative surgery | 44.0% | 27.9% | 29.3% | 35.8% |

| Symptomatic treatment | 16.0% | 20.6% | 22.0% | 14.8% |

| Stage at diagnosis1 | ||||

| Stage I | 16.0% | 23.5% | 24.4% | 25.9% |

| Stage II | 16.0% | 23.5% | 24.4% | 14.8% |

| Stage III | 8.0% | 3.0% | 3.7% | 7.4% |

| Stage IV | 60.0% | 48.5% | 47.5% | 51.9% |

Among the 131 patients not treated with R0 resection, 4.6% had a palliative resection, 55.7% a by-pass, 2.3% an exploratory laparotomy, 0.8% local treatment with laser and 36.6% had best supportive care only. Among cases with curative resection, pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed in 94.0% of cases and ampullectomy in 6.0% of cases. Eleven cases had adjuvant treatment (radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or both).

Cancer of the ampulla of Vater was often diagnosed at an advanced stage: overall, 50.8% of cases were TNM stage IV or not-resected. There was no significant variation in stage at diagnosis over the different study periods (Table 1).

Overall, 1-, 3- and 5-year relative survival rates were respectively 60.5%, 34.3%, and 27.7%. Relative survival according to the different studied variables is shown in Table 2. There was no significant improvement in survival over time. Survival was higher in patients under 60 years old than in older patients (P = 0.0012). Survival was not related to gender. Treatment and stage at diagnosis were the most important determinants of survival. The 5-year relative survival rate was 41.5% after resection for cure, 9.5% after palliative surgery and 6.7% after symptomatic treatment. Prognosis worsened with advancement of cancer stage at diagnosis. The 5-year relative survival rate varied from 60.3% for stage I to 8.0% for advanced cancers (Table 2).

| n | Relative survival | P value | |||

| 1 yr | 3 yr | 5 yr | |||

| Sex | 0.6356 | ||||

| Men | 130 | 61.9% | 35.0% | 30.2% | |

| Women | 122 | 58.7% | 33.5% | 23.8% | |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.0012 | ||||

| < 60 yr | 46 | 76.5% | 50.2% | 45.5% | |

| 60-74 yr | 89 | 62.8% | 33.9% | 24.0% | |

| > 74 yr | 117 | 51.3% | 26.7% | 19.6% | |

| Treatment | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Resection for cure | 124 | 77.8% | 48.6% | 41.5% | |

| Palliative surgery | 81 | 55.2% | 17.8% | 9.5% | |

| Symptomatic treatment | 47 | 26.5% | 17.1% | 6.7% | |

| Stage at diagnosis | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Stage I | 60 | 80.1% | 62.0% | 60.3% | |

| Stage II | 52 | 72.3% | 40.2% | 29.4% | |

| Stage III | 13 | Not calculated | |||

| Stage IV | 126 | 44.1% | 17.5% | 8.0% | |

| Period at diagnosis | 0.4526 | ||||

| 1976-1984 | 25 | 54.5% | 22.4% | 14.0% | |

| 1985-1993 | 65 | 56.4% | 31.0% | 21.6% | |

| 1994-2002 | 82 | 67.7% | 38.1% | 31.6% | |

| 2003-2009 | 80 | 59.0% | 36.0% | 30.3% | |

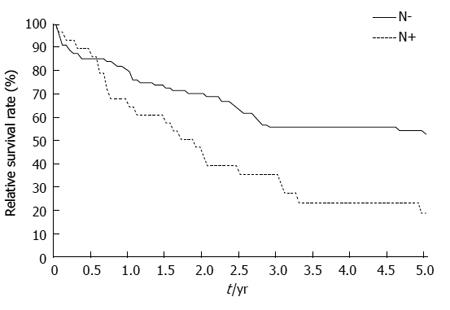

Node invasion status was an important prognostic factor (Figure 2). The 5-year relative survival rate was 54.3% in node-negative patients (85 cases) and 19.2% in node-positive patients (28 cases; P = 0.020).

A multivariate survival model based on gender, age, stage and period of diagnosis was designed. As treatment and stage at diagnosis were closely correlated, they were not included together in the multivariate analysis. The result of the model is presented in Table 3. For stage at diagnosis, the relative risk of death compared with stage I was 2.1 for stage II (P = 0.012) and 4.7 for stage IV (P < 0.001). After adjustment for sex, stage, and period at diagnosis, age at diagnosis was no longer a prognostic factor.

| HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 1.0 | ||

| Women | 0.9 | 0.7-1.3 | 0.66 |

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| < 60 yr | 1.0 | ||

| 60-74 yr | 1.3 | 0.8-2.1 | 0.54 |

| > 74 yr | 1.2 | 0.7-2.0 | 0.60 |

| Period at diagnosis | |||

| 1976-1984 | 1.0 | ||

| 1985-1993 | 1.0 | 0.6-1.7 | 0.98 |

| 1994-2002 | 0.8 | 0.5-1.5 | 0.54 |

| 2003-2009 | 0.8 | 0.5-1.4 | 0.48 |

| Stage at diagnosis | |||

| Stage I | 1.0 | ||

| Stage II | 2.1 | 1.2-3.7 | 0.012 |

| Stage III | 3.2 | 1.5-6.9 | 0.003 |

| Stage IV | 4.7 | 2.7-8.1 | < 0.001 |

This study describes the incidence and the management of cancer of the ampulla of Vater at the population level. Its strength lies in the fact that it examined all cases of the disease recorded in a long-standing cancer registry with a complete follow up in an area with a population of over one million people. All of the data were collected in a consistent fashion regardless of the time period or place of diagnosis. This study provides an unbiased picture of cancer of the ampulla of Vater in a well-defined French population over a 34-year period.

We confirm that cancer of the ampulla of Vater is still rare, accounting for less than 1% of all digestive cancers in France. Little is known about the incidence of cancer of the ampulla of Vater across the world. The four-digit Classification of the International Classification of Disease for Oncology has to be used to analyse this cancer site. Most of the time, results are reported on biliary tract cancer using only three-digit classification[1,11,12]. Population-based data on cancer of the ampulla of Vater are available from the United States[13], England[11], Shanghai (China)[14] and New Zealand[15]. Moreover, some articles used the standard American or European population, which are not an international standard and prevent direct comparison between the incidence rates in different areas of the world[1,11,16]. Age-standardized incidence rates varied between 0.3 and 0.6 per 100000 inhabitants in men, and 0.2 and 0.4 per 100000 inhabitants in women[11,14-16]. The reasons for these trends are unknown.

The descriptive epidemiology of cancer of the ampulla of Vater is relatively uniform when the few available data from affluent areas are compared[11,14-16]. All studies are characterized by a slight male predominance and an incidence that increases with age, mostly after 40 years old. The mean age at diagnosis is similar to other epithelial digestive cancers, about 70 years in men and 75 years in women. Cancer of the ampulla of Vater mostly consists of adenocarcinoma. Neuroendocrine tumours are extremely rare[17]. They originate from neuroendocrine cells located in the gastrointestinal mucosa or submucosa.

Diverging trends in incidence have been reported. In the United States, over the period 1973-2005 there was an increase in incidence in both men and women of 0.9% per year[16]. A similar trend was reported in New Zealand[15]. In England[11], incidence rates remained stable in both men and women while in France they doubled in men over the 1976-2009 period and remained stable in women. In view of these diverging trends, changes in diagnostic procedures are unlikely explanations. Few data are available about the role of environmental factors. Smoking is an identified risk factor[18]. However the sex ratio of around 1.5 is not characteristic of cancers related to smoking. Obesity was also reported as a risk factor[19], and could explain at least part of the increasing trend reported in some areas. It was also suspected that cholecystectomy increased the risk of cancer of the ampulla of Vater[20].

One of the merits of this study was to describe the management of cancer of the ampulla of Vater at a population level. The only comparable study was performed in the US within the SEER program[13]. Either surgical or endoscopic resection is currently the only potentially curative treatment. More than half of patients do not even have a resection of their cancer. This was performed in 48.3% of the cases in our series compared with 40% in the US study. This is much lower than in hospital-based series[21,22]. This discrepancy is not surprising. Hospital data are provided by specialized units and as such cannot be used as a reference because of unavailable selection bias, in particular in surgical series. The lower age at diagnosis reported in hospital series indicates that elderly patients are less frequently managed in specialized units.

Nowadays, pancreatoduodenectomy is the standard surgical strategy for curative treatment of cancer of the ampulla of Vater and is still associated with a high operative mortality rate[4]. This was 8.6% in our study and 8% in a US study conducted within the SEER program[13]. The present study and the SEER program study provided a non-biased estimation of operative mortality after resection of cancer of the ampulla of Vater. It is higher than the operative mortality rate reported by specialised centers[21,22] with selected accrual. Operative mortality after surgery for cure for pancreatic cancer was similar (11%) over the study period in the same region[23]. For this reason, local resection by endoscopic ampullectomy has been proposed as an alternative for the treatment of early cancer of the ampulla of Vater in particular in elderly patients[7]. In two series of resected cancer of the ampulla of Vater, it was shown that a limited resection was safe - in the absence of lymph node metastasis - if the cancer was less than 2 cm in size, and if the tumour was well differentiated without invasion of the duodenum or the biliary or pancreatic duct as determined by endoscopic ultrasonography[24,25]. These findings suggest that endoscopic ampullectomy can be an alternative to pancreatoduodenectomy in strictly selected patients. In our series, endoscopic ampullectomy was performed in 6% of resected cases.

It is disappointing that there have been no major improvements over time in the proportion of cases resected for cure. This suggests that improvements in imaging have not contributed to an earlier diagnosis. The lateness of symptoms can explain why only minor improvements in the management of cancer of the ampulla of Vater can be expected from the development of diagnosis strategies. A long time can pass before complete obstruction of the biliary tract or anaemia occurs. This explains the major dilatation of the intra and extra hepatic biliary tract seen at diagnosis.

The 5-year relative survival rate was low with only one quarter of patients still alive. However, this is higher than for pancreatic or extra-hepatic biliary tract cancers. In Burgundy, the 5-year relative survival rates for these two cancers were 4%[23] and 8%[26], respectively.

For cancer of the ampulla of Vater, there were important discrepancies in survival rates in different areas. The overall 5-year relative survival rates were 47% in the United States[13], 28% in Burgundy, 21% in England[11] and 20% in Eindhoven[27]. Stage at diagnosis is probably the main explanation for the differences. The proportion of stage I was 37% in the US compared with 24% in Burgundy.

Age and stage at diagnosis, as well as treatment modalities were significant prognostic factors in the univariate analysis. Because stage at diagnosis and treatment correlated with each other, only stage at diagnosis was included in the multivariate analysis. In the multivariate analysis, age was no longer a significant prognostic factor, suggesting that stage at diagnosis explained the poor survival rate in the oldest age group. Stage at diagnosis remained the only significant prognostic factor. The period of diagnosis did not influence survival. It is not surprising that in the absence of any improvement in the proportion of cases resected for cure, or in the proportion of early stage cancers at diagnosis, survival rates remained unchanged.

In the current study, we confirmed that lymph node status is a main prognostic factor: survival rates decreased significantly in cases of lymph node invasion. In the US study[13] similar results were reported. The signifiance of stage III of the TNM classification can be discussed. In our study, only 5.1% patients had stage III disease. Resectable locally-advanced cancers are rare and as they have a poor prognosis, they are similar to metastatic or unresectable cancers.

In our study, only eleven patients had adjuvant treatment after R0 resection (8.9%). This is not surprising since radiochemotherapy with 5-Fluorouracil was not shown to improve 5-year relative survival compared with patients who did not receive adjuvant treatment[28,29]. A randomized study on the effect of radiochemotherapy was also negative[30]. In another trial[31] that compared chemotherapy (Fluorouracil plus folinic acid or gemcitabine) with observation alone, adjuvant chemotherapy did not significantly improve survival. However, the benefits of chemotherapy were suggested in a multivariate analysis with a hazard ratio of 0.73 (P = 0.048). More data are necessary in order to recommend chemotherapy or not as a standard adjuvant treatment.

The current study is one of the rare population-based studies about cancer of the ampulla of Vater. The main advantage is that it provides a real picture of trends in the incidence and management of the disease in a well-defined French population. Cancer of the ampulla of Vater is still uncommon, but the incidence rate is increasing in men. This trend is not well explained. Only minor improvements have been made in the management of cancer of the ampulla of Vater over the last thirty-four years, which explains why survival rates have remained stable. Stage at diagnosis is the main prognostic factor, and about half of the cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage. Because of the rarity of cancer of the ampulla of Vater, it seems difficult to identify a high-risk population to facilitate earlier diagnosis. In the short term more effective systematic treatments are needed. Recent collaborative studies have shown that phase III trials are feasible.

The Burgundy digestive cancer registry receives support from the National Cancer Institute, and the Burgundy regional council.

Epidemiological characteristics of cancer of the ampulla of Vater (CAV) are not well known, because it is a rare cancer, and also because most epidemiological studies have considered CAV, of the extra hepatic bile duct and sometimes of the gallbladder as a single entity.

Most of the available data is provided by specialised centres and thus cannot be used as a reference because of unavoidable selection bias. Population-based studies using data from registries, which record all cases in a well-defined population, are the best way to assess the epidemiological characteristics, management and real prognosis.

This study is based on over 256 cases of this rare cancer, identified by a population based study, which is as far as people are aware the largest population-based study of CAV dealing not only with incidence but also with management.

The authors demonstrate that, over a 34-year period (1976–2009), CAV is still uncommon, but its incidence increased for men. Diagnosis is often made at an advanced stage, dramatically worsening the prognosis. Survival did not improve between 1976 and 2009. The authors confirmed that lymph node status is a main prognostic factor. Stage at diagnosis was the only independent prognostic factor in a multivariate analysis.

Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater is a rare malignant tumor arising within 2 cm of the distal end of the common bile duct, where it passes through the wall of the duodenum and ampullary papilla.

The study Rostain et al aims at providing trends in incidence, management and survival of cancer of the ampulla of Vater (CAV) in a well-defined French population. The study is original given the fact that CAV is a rare cancer. The statistical methodology is appropriate.

P- Reviewer: Dalamaga M, Shivshankar P S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Goodman MT, Yamamoto J. Descriptive study of gallbladder, extrahepatic bile duct, and ampullary cancers in the United States, 1997-2002. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:415-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Urbach DR, Swanstrom LL, Khajanchee YS, Hansen PD. Incidence of cancer of the pancreas, extrahepatic bile duct and ampulla of Vater in the United States, before and after the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2001;181:526-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Beger HG, Treitschke F, Gansauge F, Harada N, Hiki N, Mattfeldt T. Tumor of the ampulla of Vater: experience with local or radical resection in 171 consecutively treated patients. Arch Surg. 1999;134:526-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yoon YS, Kim SW, Park SJ, Lee HS, Jang JY, Choi MG, Kim WH, Lee KU, Park YH. Clinicopathologic analysis of early ampullary cancers with a focus on the feasibility of ampullectomy. Ann Surg. 2005;242:92-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee SY, Jang KT, Lee KT, Lee JK, Choi SH, Heo JS, Paik SW, Rhee JC. Can endoscopic resection be applied for early stage ampulla of Vater cancer? Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:783-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Seewald S, Omar S, Soehendra N. Endoscopic resection of tumors of the ampulla of Vater: how far up and how deep down can we go? Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:789-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yoon SM, Kim MH, Kim MJ, Jang SJ, Lee TY, Kwon S, Oh HC, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK. Focal early stage cancer in ampullary adenoma: surgery or endoscopic papillectomy? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:701-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | ICD-03 WHO. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation 2000; . |

| 9. | Edge SB, Byrd DR, Carducci M, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer 2009; . |

| 10. | Estève J, Benhamou E, Croasdale M, Raymond L. Relative survival and the estimation of net survival: elements for further discussion. Stat Med. 1990;9:529-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Coupland VH, Kocher HM, Berry DP, Allum W, Linklater KM, Konfortion J, Møller H, Davies EA. Incidence and survival for hepatic, pancreatic and biliary cancers in England between 1998 and 2007. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36:e207-e214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Miyakawa S, Ishihara S, Horiguchi A, Takada T, Miyazaki M, Nagakawa T. Biliary tract cancer treatment: 5,584 results from the Biliary Tract Cancer Statistics Registry from 1998 to 2004 in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Manunga J, Tomlinson JS, Reber HA, Ko CY, Hines OJ. Survival after resection of ampullary carcinoma: a national population-based study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1820-1827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hsing AW, Gao YT, Devesa SS, Jin F, Fraumeni JF. Rising incidence of biliary tract cancers in Shanghai, China. Int J Cancer. 1998;75:368-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Koea J, Phillips A, Lawes C, Rodgers M, Windsor J, McCall J. Gall bladder cancer, extrahepatic bile duct cancer and ampullary carcinoma in New Zealand: Demographics, pathology and survival. ANZ J Surg. 2002;72:857-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Albores-Saavedra J, Schwartz AM, Batich K, Henson DE. Cancers of the ampulla of vater: demographics, morphology, and survival based on 5,625 cases from the SEER program. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:598-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nikou GC, Toubanakis C, Moulakakis KG, Pavlatos S, Kosmidis C, Mallas E, Safioleas P, Sakorafas GH, Safioleas MC. Carcinoid tumors of the duodenum and the ampulla of Vater: current diagnostic and therapeutic approach in a series of 8 patients. Case series. Int J Surg. 2011;9:248-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chow WH, McLaughlin JK, Menck HR, Mack TM. Risk factors for extrahepatic bile duct cancers: Los Angeles County, California (USA). Cancer Causes Control. 1994;5:267-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Samanic C, Gridley G, Chow WH, Lubin J, Hoover RN, Fraumeni JF. Obesity and cancer risk among white and black United States veterans. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:35-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chow WH, Johansen C, Gridley G, Mellemkjaer L, Olsen JH, Fraumeni JF. Gallstones, cholecystectomy and risk of cancers of the liver, biliary tract and pancreas. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:640-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Howe JR, Klimstra DS, Moccia RD, Conlon KC, Brennan MF. Factors predictive of survival in ampullary carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1998;228:87-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Talamini MA, Moesinger RC, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Hruban RH, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL. Adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. A 28-year experience. Ann Surg. 1997;225:590-599; discussion 599-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | David M, Lepage C, Jouve JL, Jooste V, Chauvenet M, Faivre J, Bouvier AM. Management and prognosis of pancreatic cancer over a 30-year period. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:215-218. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Woo SM, Ryu JK, Lee SH, Lee WJ, Hwang JH, Yoo JW, Park JK, Kang GH, Kim YT, Yoon YB. Feasibility of endoscopic papillectomy in early stage ampulla of Vater cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:120-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Aiura K, Hibi T, Fujisaki H, Kitago M, Tanabe M, Kawachi S, Itano O, Shinoda M, Yagi H, Masugi Y. Proposed indications for limited resection of early ampulla of Vater carcinoma: clinico-histopathological criteria to confirm cure. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:707-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lepage C, Cottet V, Chauvenet M, Phelip JM, Bedenne L, Faivre J, Bouvier AM. Trends in the incidence and management of biliary tract cancer: a French population-based study. J Hepatol. 2011;54:306-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Coeberg JW, Van der Heijden LH, Janssen-Heijnen MLG. Cancer incidence and survival in the southeast of Netherland. 1955-1994. Eindhoven: IKZ 1995; . |

| 28. | Sikora SS, Balachandran P, Dimri K, Rastogi N, Kumar A, Saxena R, Kapoor VK. Adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy in ampullary cancers. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:158-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kim K, Chie EK, Jang JY, Kim SW, Oh DY, Im SA, Kim TY, Bang YJ, Ha SW. Role of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy for ampulla of Vater cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:436-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Sahmoud T, van Pel R, Couvreur ML, Veenhof CH, Arnaud JP, Gonzalez DG, de Wit LT, Hennipman A. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg. 1999;230:776-782; discussion 782-784. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Neoptolemos JP, Moore MJ, Cox TF, Valle JW, Palmer DH, McDonald AC, Carter R, Tebbutt NC, Dervenis C, Smith D. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid or gemcitabine vs observation on survival in patients with resected periampullary adenocarcinoma: the ESPAC-3 periampullary cancer randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:147-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 444] [Cited by in RCA: 463] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |