Published online Jun 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7197

Revised: December 11, 2013

Accepted: January 3, 2014

Published online: June 21, 2014

Processing time: 246 Days and 18 Hours

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) chronically infects more than 350 million people worldwide. HBV causes acute and chronic hepatitis, and is one of the major causes of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. There exist complex interactions between HBV and the immune system including adaptive and innate immunity. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and TLR-signaling pathways are important parts of the innate immune response in HBV infections. It is well known that TLR-ligands could suppress HBV replication and that TLRs play important roles in anti-viral defense. Previous immunological studies demonstrated that HBV e antigen (HBeAg) is more efficient at eliciting T-cell tolerance, including production of specific cytokines IL-2 and interferon gamma, than HBV core antigen. HBeAg downregulates cytokine production in hepatocytes by the inhibition of MAPK or NF-κB activation through the interaction with receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are also able to regulate various biological processes such as the innate immune response. When the expressions of approximately 1000 miRNAs were compared between human hepatoma cells HepG2 and HepG2.2.15, which could produce HBV virion that infects chimpanzees, using real-time RT-PCR, we observed several different expression levels in miRNAs related to TLRs. Although we and others have shown that HBV modulates the host immune response, several of the miRNAs seem to be involved in the TLR signaling pathways. The possibility that alteration of these miRNAs during HBV infection might play a critical role in innate immunity against HBV infection should be considered. This article is intended to comprehensively review the association between HBV and innate immunity, and to discuss the role of miRNAs in the innate immune response to HBV infection.

Core tip: Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the leading cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma in the world. HBV could interact with the host’s innate and adaptive immune responses to establish chronic infection. HBV also interacts with Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and TLR signaling pathways, and regulates host immune responses through the regulation of microRNAs (miRNAs) to some extent. This article focuses on the involvement of miRNA in the association between HBV and TLR signaling pathways and reviews the miRNAs involved in HBV infection.

- Citation: Jiang X, Kanda T, Wu S, Nakamura M, Miyamura T, Nakamoto S, Banerjee A, Yokosuka O. Regulation of microRNA by hepatitis B virus infection and their possible association with control of innate immunity. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(23): 7197-7206

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i23/7197.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7197

Hepatitis B virus (HBV), a member of hepadona viridae, has partially circular double-stranded DNA genome, 3.2 kb in length[1]. It contains four overlapping open reading frames that encode seven proteins: the precore protein, also known serologically as HBe antigen (HBeAg), the core protein (HBcAg), viral polymerase, three forms of the envelope protein known as S antigen (HBsAg) and X (HBx) protein[1,2]. HBV as well as hepatitis C virus (HCV) causes acute and chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[3]. Hepatic cirrhosis and HCC are the most common causes of death in patients with chronic liver disease[4].

The outcome of HBV infection is the result of complex interactions between HBV and the immune system including adaptive and innate immunity[5,6]. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are important parts of the innate immune response in hepatitis virus infections[7]. There are several reports about the important role of TLRs and TLR-mediated signaling in the pathogenesis and outcome of HBV infection[2,5-11].

MicroRNA (miRNA) is one of the endogenous noncoding small RNAs, approximately 18-22 nucleotides in size, a post-transcriptional regulator that binds to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of the target gene messenger RNA, usually resulting in cleavage or inhibiting translation of the target gene mRNA[12,13]. It is estimated that the human genome may encode over 2000 miRNAs, which may control about 60% of the human genome[14,15]. Physiologically, miRNAs are able to regulate various biological processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis, neuroprocesses, carcinogenesis and immune response[16-18]. This article is intended to comprehensively review the association between HBV and innate immunity, and to discuss the role of miRNAs in the innate immune response to HBV infection.

Interferons (IFNs) play an important role in the innate immune response to virus infection. IFN-α and IFN-β (type I IFNs) are secreted by almost all virus-infected cells including hepatocytes and by specialized blood lymphocytes. In contrast, the production of IFN-γ (type II IFN) is restricted to cells of the immune system, such as natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, and T cells. On the other hand, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) primarily initiates innate immune response and triggers acquired immune responses[19]. TNF-α-induced apoptosis is important for clearance of hepatocytes infected with HBV and HCV, and IFN-γ accelerates the killing of theses hepatocytes[19,20]. The previous studies demonstrated that TNF-α and IFN-γ downregulate HBV gene expression in the liver of HBV transgenic mice by posttranscriptionally destabilizing the viral mRNA[21-23]. It has been widely believed that the cytotoxic T lymphocyte response clears viral infections by killing infected cells. However, Chisari’s group[21-24] reported that noncytopathic clearance of HBV from hepatocytes by cytokines, which abolish viral replication and HBV gene expression, is another important mechanism. Isogawa et al[24] reported that TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, TLR7 and TLR9 ligands could induce antiviral cytokines and inhibit HBV replication in HBV transgenic mice, thereby indicating TLR activation as a powerful strategy for the treatment of chronic HBV infection. HBV replication can be controlled by innate immune response, involving TLRs, if it is activated in hepatocytes[24]. Together, these facts indicate that innate immunity including TLR signaling plays an important role in the pathogenesis of HBV infection.

TLRs, germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), can play a central role in host cell recognition and response to various pathogens such as viruses[25]. TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR6 are expressed on the cell surface while TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 are expressed within intracellular vesicles. TLR3, TLR7/8 and TLR9 are involved in the recognition of viral nucleotides such as double-stranded RNA, single-stranded RNA and DNA, respectively[26]. Other than TLRs, membrane-bound C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), cytosolic proteins such as NOD-like receptors (NLRs) and RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), which include retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I ), melanoma differentiation antigen 5 (MDA5), and lipophosphoglycan biosynthetic protein 2 (LPG2), and unidentified proteins that mediate sensing of cytosolic DNA or retrovirus infection, are also involved in the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)[25].

TLRs play a crucial role in defending against pathogenic infection through the induction of inflammatory cytokines and type I IFNs by myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88)-dependent and MYD88-independent pathway. In the MYD88-dependent pathway, MYD88 recruits a set of signal cascades such as MAPK and NF-κB through receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase (RIPK/RIP). In the MYD88-independent pathway, TLR3 activates NF-κB and MAPKs through RIPK. TLR3 also activates IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and IRF7 via TRIF/TICAM-1, inducing the production of type I IFN. The activated NF-κB and IRFs are translocated to the nucleus. NF-κB and MAPKs initiate the transcription of inflammatory cytokine genes, whereas IRFs initiate the transcription of type I IFN[2]. RIG-I and MDA5 pathways can also activate IRF3 to produce type I IFNs. RNA helicases RIG-I and MDA5, specific receptors for double-stranded RNA, and the downstream mitochondrial effector known as CARDIF/MAVS/VISA/IPS-1, are also major pathways for type I IFN induction.

TLRs have been recognized as playing an important role in the pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis B[8]. NF-κB is activated by three TLR adaptors, MYD88, Toll/interleukin (IL)-1 receptor (TIR)-domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFNβ (TRIF), and IFN promoter stimulator 1 (IPS-1), to elicit anti-HBV response in both HepG2 and Huh7 cells[27]. Down-regulations of TLR7 and TLR9 mRNA were observed in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of HBV-infected patients[28]. Chen et al[29] reported that TLR1, TLR2, TLR4 and TLR6 transcripts were also downregulated in PBMC of chronic hepatitis B patients. After being challenged by TLR2 and TLR4 ligands, cytokine production was impaired in PBMC of chronic hepatitis B patients on the basis of the levels of plasma HBsAg[29]. Xie et al[30] reported that HBV infection results in reduced frequency of circulating plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and their functional impairment via inhibiting TLR9 expression. HBV replication suppresses the TLR-stimulated expression of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF, IL6) and the activation of IRF3[31]. It has also been reported that HBV could target RIG-I signaling by HBx-mediated IPS-1 down-regulation, thereby attenuating the antiviral response of the innate immune system[32].

The HBV precore/core region of HBV genome also encodes HBeAg as well as the HBV core. The precore stop codon prevents the formation of precore protein and HBeAg[2,33]. The existence of HBeAg in serum is known to be a marker of a high degree of viral infectivity. In Japan, the major HBV genotypes are B and C, but our previous study[34] revealed that the precore mutation A1896 and the core promoter mutations at nt1762 and 1764 were found more frequently in acute liver failure than in acute hepatitis, and HBV genotype B was predominant in acute liver failure. It has also been shown that acute liver failure occasionally occurs in persons who are negative for HBeAg[35,36]. It is well known that perinatal transmission of HBV occurs in about 10%-20% of HBeAg-negative mothers without prevention of perinatal HBV transmission by combined passive and active immunoprophylaxis, and the babies are at risk of developing fulminant hepatitis[37]. Chronic hepatitis B with high HBV DNA and ant-HBe is associated with a severe and evolutive liver disease[38]. These clinical findings could be assumed to have immune tolerance for HBeAg, although the function of HBV precore or HBeAg is unknown. Previous immunological studies[39-41] demonstrated that HBeAg is more efficient at eliciting T-cell tolerance, including production of its specific cytokines IL-2 and IFN-γ, than HBV core antigen. We also demonstrated that HBeAg expression inhibits IFN and cytokine production[2] and that HBeAg physically associates with RIPK2 and regulates IL-6 gene expression[6]. Visvanathan et al[42] reported that the expression of TLR2 on hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and peripheral monocytes was significantly reduced in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients. Thus, HBV seems to have evolved strategies that block the effector mechanisms induced through IFN and/or cytokine signaling pathways, similar to other viruses[19].

HepG2.2.15 cells assemble and secrete HBV virion that infects chimpanzees[43,44]. We examined the expression of approximately 1000 miRNAs in the human hepatoma cells HepG2.2.15 and HepG2 using real-time RT-PCR, the most sensitive technique for mRNA detection and quantification[45,46].

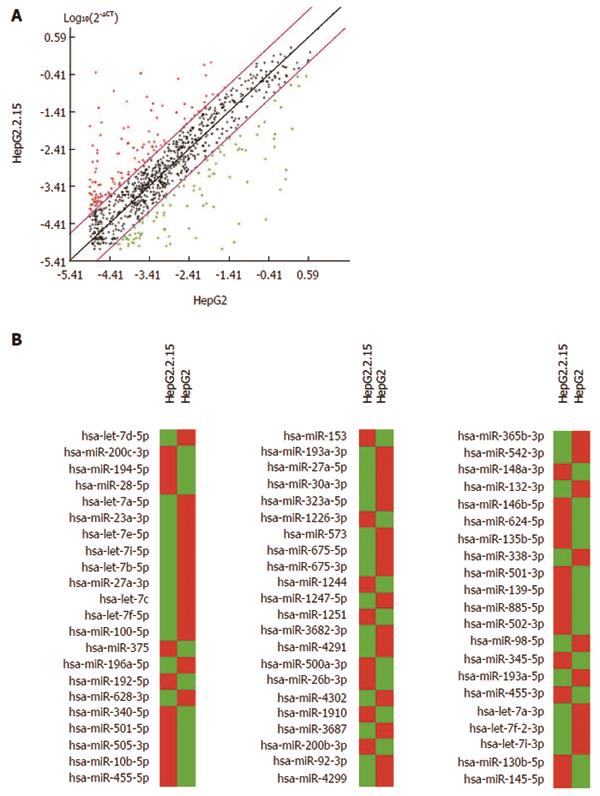

First, 1008 miRNAs were examined in the hepatoma cells HepG2.2.15 and HepG2, using quantitative real-time RT-PCR with specific primers (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). SNORD61, SNORD68, SNORD72, SNORD95, SNORD96A and RNU6-2 were used as endogenous controls to normalize expression to determine the fold-change in miRNA expression between the test sample (HepG2.2.15) and control sample (HepG2) by 2-ddCT (comparative cycle threshold) method[21]. MiRNAs were annotated by Entrez Gene (NCBI, Bethesda, MD, United States), accessed on 2/27/2013. Data were analyzed with miRNA PCR array data analysis software (http://www.sabiosciences.com/mirnaArrayDataAnalysis.php). Scatter plot analysis is shown in Figure 1A. There were differences in expression between HepG2 and HepG2.2.15 (Figure 1B).

We then excluded 599 miRNAs according to the following criteria: (1) average threshold cycle was relatively high (> 30) in either HepG2 or HepG2.2.15, and was reasonably low in the other samples (< 30); (2) average threshold cycle was relatively high (> 30), meaning that its relative expression level was low, in both HepG2 and HepG2.2.15; and (3) average threshold cycle was either not determined or was greater than the defined cut-off value (default 35) in both samples, meaning that its expression was undetected, making this fold-change result erroneous and uninterpretable.

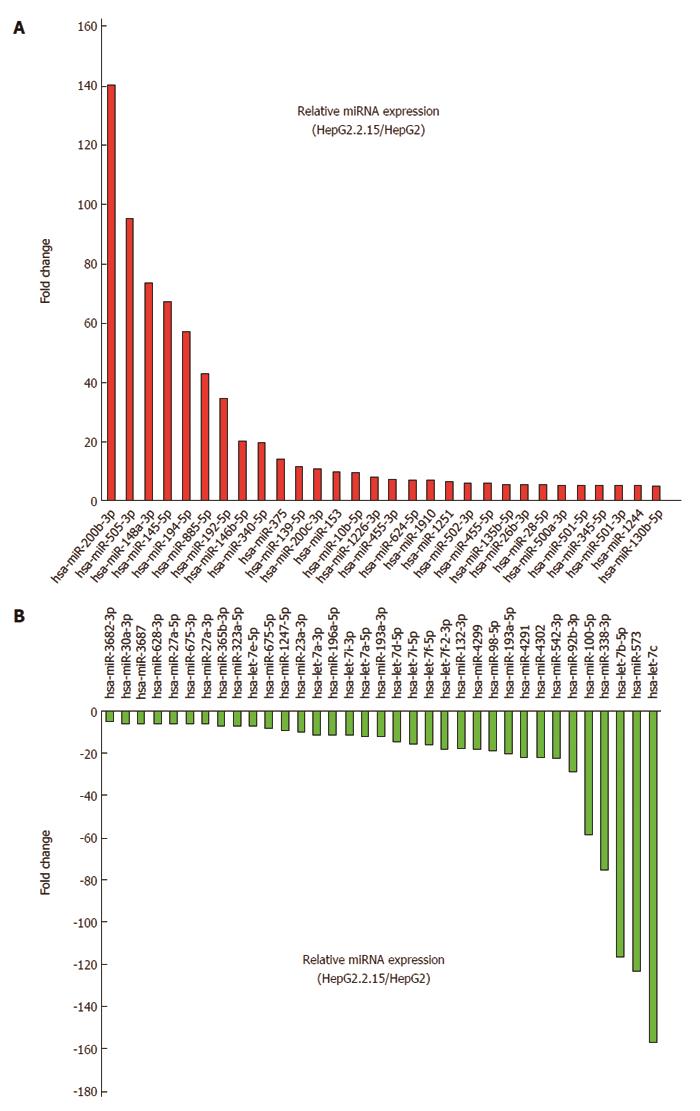

Out of 409 miRNAs examined, 30 (7.3%) were upregulated by 5-fold or greater in HepG2.2.15 compared to HepG2. Twelve miRNAs (miR-200b-3p, miR-505-3p, miR-148a-3p, miR-145-5p, miR-194-5p, miR-885-5p, miR-192-5p, miR-146b-5p, miR-340-5p, miR-375, miR-139-5p and miR-200c-3p) were upregulated 10-fold or more in HepG2.2.15 cells. MiRNAs upregulated 5-fold or more are shown in Figures 1B and 2A. On the other hand, out of 409 miRNAs, 35 (8.6%) were downregulated 5-fold or more in HepG2.2.15 compared to HepG2. Twenty-two miRNAs (let-7c, miR-573, let-7b-5p, miR-338-3p, miR-100-5p, miR-92b-3p, miR-542-3p, miR-4302, miR-4291, miR-193a-5p, miR-98-5p, miR-4299, miR-132-3p, let-7f-2-3p, let-7f-5p, let-7i-5p, let-7d-5p, miR-193a-3p, let-7a-5p, let-7i-3p, miR-196a-p and let-7a-3p) were downregulated 10-fold or more in HepG2.2.15 cells. MiRNAs downregulated 5-fold or more are shown in Figures 1B and 2B.

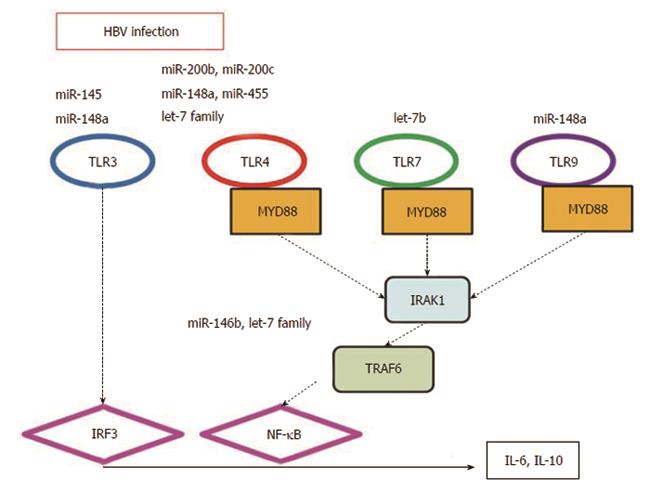

Innate immunity represents the first line of defense against HBV, and we and others have reported its importance in the persistence of HBV infection[2,5-11]. So, we focused on miRNAs related to the TLR pathway. Among miRNAs upregulated 5-fold or more in HepG2.2.15 cells, 7 miRNAs (miR-200b-3p, miR-148a-3p, miR-145-5p, miR-146b-5p, miR-200c-3p, miR-455-3p and miR-455-5p) were reported to be related to TLR pathways (Table 1). MiRNAs miR-200b and miR-200c are the factors that modify the efficiency of TLR4 signaling through MYD88 in HEK293 cells[47]. TLR3, TLR4 and TLR9 agonists upregulated miR-148/152 expression and downregulated calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) in dendritic cells (DCs) on maturation[48]. Thus miR-148/152 can act as fine-tuners in regulating the innate response and antigen-presenting capacity of DCs[48]. Exogenous miR-145 promoted IFN-β induction by targeting the suppressor of cytokine signaling 7 (SOCS7), through the nuclear translocation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and SOCS7-silencing enhanced IFN-γ induction by stimulation with TLR3 ligand, poly(I-C)[49]. MiR-146 plays a role in the control of TLR and cytokine signaling through a negative feedback regulation loop involving down-regulation of interleukin (IL)-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) protein levels[50]. MiR-455 was involved in the TLR4 signaling pathway through E2F1 transcription factor[51].

| MicroRNAs | Genomic location | Fold changes | Description of target molecules/pathways | Ref. |

| miR-200b-3p | 1p36.33 | 140.15 | TLR4 signaling through MyD88-dependent pathway | [47] |

| miR-148a-3p | 7p15.2 | 73.36 | TLR3, TLR4 and TLR9 agonists upregulated miR-148/152 expression | [48] |

| miR-145-5p | 5q32 | 66.97 | miR-145 promoted interferon-β induction by SOCS7 | [49] |

| miR-146b-5p | 10q24.32 | 20.05 | TNF receptor-associated factor 6 and IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 | [50] |

| miR-200c-3p | 12p13.31 | 10.75 | TLR4 signaling through MyD88-dependent pathway | [47] |

| miR-455-3p | 9q32 | 7.36 | miR-455 was involved in TLR4 signaling pathway through E2F1 transcription factor | [51] |

| miR-455-5p | 9q32 | 5.76 | miR-455 was involved in TLR4 signaling pathway through E2F1 transcription factor | [51] |

Among miRNAs downregulated 5-fold or more in HepG2.2.15 cells, 8 miRNAs (let-7e-5p, let-7a-3p, let-7i-3p, let-7a-5p, let-7d-5p, let-7i-5p, miR-132-3p and let-7b-5p) were reported to be related to TLR pathways (Table 2). Protein kinase Akt1, which is activated by the TLR4-ligand lipopolysaccharide (LPS), positively regulated let-7e and miR-181c but negatively regulated miR-155 and miR-125b[52]. Repression of the let-7 family relieves IL-6 and IL-10 mRNAs from negative post-transcriptional control in the TLR4 signaling pathway[53], and the miRNAs let-7i and let-7b activate TLR4 and TLR7, respectively[54-56].

| MicroRNAs | Genomic location | Fold changes | Description of target molecules/pathways | Ref. |

| let-7e-5p | 19q13.33 | -7.29 | Akt1 activated by TLR4-ligand LPS, positively regulated let-7e | [52] |

| let-7a-3p | 9q22.32 | -11.44 | Repression of let-7 family relieves IL-6 and IL-10 mRNAs from negative post-transcriptional control in TLR4 signaling pathway | [53] |

| 11q24.1 | ||||

| 22q13.31 | ||||

| let-7i-3p | 12q14.1 | -11.57 | let-7i regulates Toll-like receptor 4 expression | [54] |

| let-7a-5p | 9q22.32 11q24.1 22q13.31 | -11.96 | Repression of let-7 family relieves IL-6 and IL-10 mRNAs from negative post-transcriptional control in TLR4 signaling pathway | [53] |

| let-7d-5p | 9q22.32 | -14.03 | Repression of let-7 family relieves IL-6 and IL-10 mRNAs from negative post-transcriptional control in TLR4 signaling pathway | [53] |

| let-7i-5p | 12q14.1 | -15.10 | let-7i regulates Toll-like receptor 4 expression | [54,55] |

| miR-132-3p | 17p13.3 | -18.18 | TNF receptor-associated factor 6 and IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 | [56] |

| let-7b-5p | 22q13.31 | -116.31 | let-7b activates TLR 7 | [56] |

In the present study, 30 and 35 miRNAs were upregulated and downregulated, respectively, by 5-fold or greater in HepG2.2.15 compared to its parental cell line HepG2. These results indicate that miRNAs could play an important role in chronic persistent HBV infection. Su et al[57] reported that miR-155 enhances innate antiviral immunity through promoting the JAK/STAT signaling pathway by targeting SOCS1, inhibiting HBV replication. The possibility cannot be ruled out that HBV persistently infects hepatocytes through the regulation of miRNAs.

We also speculated that several of the miRNAs involved in the TLR signaling pathway play a critical role in innate immunity against HBV infection[5,24] (Figure 3). It has been reported that miR-21[58], miR-22[59,60], miR-122[58], miR-194[61] and miR-219-1[62] are associated with chronic persistent HBV infection as well as its clearance. In the present study, miR-194 was upregulated 10-fold or more in HepG2.2.15 cells.

MicroRNAs miR-122 and miR-130a play an important role in chronic hepatitis C[63,64]. Regulation of miRNAs also plays an important role in HIV infection[65]. In HCV infection, a set of miRNAs that regulate host immune response are modulated[66]. We and others have demonstrated that HBV modulates the host immune response. It might be possible that HBV as well as HCV regulates host immune response through the regulation of miRNAs in some steps toward chronic infection. MiRNAs and their regulation play a critical role in HBV infection, and HBV may regulate the TLR signaling pathway through the regulation of miRNAs.

P- Reviewers: Greene CM, Ryffel B, Seya T, Vulcano M S- Editor: Cui XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Wooddell CI, Rozema DB, Hossbach M, John M, Hamilton HL, Chu Q, Hegge JO, Klein JJ, Wakefield DH, Oropeza CE. Hepatocyte-targeted RNAi therapeutics for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Mol Ther. 2013;21:973-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wu S, Kanda T, Imazeki F, Arai M, Yonemitsu Y, Nakamoto S, Fujiwara K, Fukai K, Nomura F, Yokosuka O. Hepatitis B virus e antigen downregulates cytokine production in human hepatoma cell lines. Viral Immunol. 2010;23:467-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264-1273.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2183] [Cited by in RCA: 2508] [Article Influence: 192.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Luedde T, Schwabe RF. NF-κB in the liver--linking injury, fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:108-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1094] [Cited by in RCA: 1089] [Article Influence: 77.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ait-Goughoulte M, Lucifora J, Zoulim F, Durantel D. Innate antiviral immune responses to hepatitis B virus. Viruses. 2010;2:1394-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Wu S, Kanda T, Imazeki F, Nakamoto S, Tanaka T, Arai M, Roger T, Shirasawa H, Nomura F, Yokosuka O. Hepatitis B virus e antigen physically associates with receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 2 and regulates IL-6 gene expression. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:415-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Sawhney R, Visvanathan K. Polymorphisms of toll-like receptors and their pathways in viral hepatitis. Antivir Ther. 2011;16:443-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Preiss S, Thompson A, Chen X, Rodgers S, Markovska V, Desmond P, Visvanathan K, Li K, Locarnini S, Revill P. Characterization of the innate immune signalling pathways in hepatocyte cell lines. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:888-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Thompson AJ, Colledge D, Rodgers S, Wilson R, Revill P, Desmond P, Mansell A, Visvanathan K, Locarnini S. Stimulation of the interleukin-1 receptor and Toll-like receptor 2 inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in hepatoma cell lines in vitro. Antivir Ther. 2009;14:797-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lang T, Lo C, Skinner N, Locarnini S, Visvanathan K, Mansell A. The hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) targets and suppresses activation of the toll-like receptor signaling pathway. J Hepatol. 2011;55:762-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 11. | Wilson R, Warner N, Ryan K, Selleck L, Colledge D, Rodgers S, Li K, Revill P, Locarnini S. The hepatitis B e antigen suppresses IL-1β-mediated NF-κB activation in hepatocytes. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:e499-e507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25833] [Cited by in RCA: 27845] [Article Influence: 1326.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tanaka T, Arai M, Wu S, Kanda T, Miyauchi H, Imazeki F, Matsubara H, Yokosuka O. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-373 plays an important role in regulating cell proliferation in colon cancer. Oncol Rep. 2011;26:1329-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bentwich I, Avniel A, Karov Y, Aharonov R, Gilad S, Barad O, Barzilai A, Einat P, Einav U, Meiri E. Identification of hundreds of conserved and nonconserved human microRNAs. Nat Genet. 2005;37:766-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1342] [Cited by in RCA: 1383] [Article Influence: 69.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8847] [Cited by in RCA: 9285] [Article Influence: 464.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Miska EA. How microRNAs control cell division, differentiation and death. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:563-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 607] [Cited by in RCA: 650] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kutay H, Bai S, Datta J, Motiwala T, Pogribny I, Frankel W, Jacob ST, Ghoshal K. Downregulation of miR-122 in the rodent and human hepatocellular carcinomas. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:671-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 488] [Cited by in RCA: 467] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Visone R, Petrocca F, Croce CM. Micro-RNAs in gastrointestinal and liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1866-1869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kanda T, Steele R, Ray R, Ray RB. Inhibition of intrahepatic gamma interferon production by hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A in transgenic mice. J Virol. 2009;83:8463-8469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wieland SF, Chisari FV. Stealth and cunning: hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses. J Virol. 2005;79:9369-9380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 339] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tsui LV, Guidotti LG, Ishikawa T, Chisari FV. Posttranscriptional clearance of hepatitis B virus RNA by cytotoxic T lymphocyte-activated hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12398-12402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Guidotti LG, Ishikawa T, Hobbs MV, Matzke B, Schreiber R, Chisari FV. Intracellular inactivation of the hepatitis B virus by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunity. 1996;4:25-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 840] [Cited by in RCA: 840] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Heise T, Guidotti LG, Cavanaugh VJ, Chisari FV. Hepatitis B virus RNA-binding proteins associated with cytokine-induced clearance of viral RNA from the liver of transgenic mice. J Virol. 1999;73:474-481. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Isogawa M, Robek MD, Furuichi Y, Chisari FV. Toll-like receptor signaling inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in vivo. J Virol. 2005;79:7269-7272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with other innate receptors in infection and immunity. Immunity. 2011;34:637-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2423] [Cited by in RCA: 2742] [Article Influence: 195.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Blasius AL, Beutler B. Intracellular toll-like receptors. Immunity. 2010;32:305-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 822] [Cited by in RCA: 951] [Article Influence: 63.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Guo H, Jiang D, Ma D, Chang J, Dougherty AM, Cuconati A, Block TM, Guo JT. Activation of pattern recognition receptor-mediated innate immunity inhibits the replication of hepatitis B virus in human hepatocyte-derived cells. J Virol. 2009;83:847-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Xu N, Yao HP, Sun Z, Chen Z. Toll-like receptor 7 and 9 expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with chronic hepatitis B and related hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29:239-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chen Z, Cheng Y, Xu Y, Liao J, Zhang X, Hu Y, Zhang Q, Wang J, Zhang Z, Shen F. Expression profiles and function of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of chronic hepatitis B patients. Clin Immunol. 2008;128:400-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Xie Q, Shen HC, Jia NN, Wang H, Lin LY, An BY, Gui HL, Guo SM, Cai W, Yu H. Patients with chronic hepatitis B infection display deficiency of plasmacytoid dendritic cells with reduced expression of TLR9. Microbes Infect. 2009;11:515-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wu J, Meng Z, Jiang M, Pei R, Trippler M, Broering R, Bucchi A, Sowa JP, Dittmer U, Yang D. Hepatitis B virus suppresses toll-like receptor-mediated innate immune responses in murine parenchymal and nonparenchymal liver cells. Hepatology. 2009;49:1132-1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 32. | Wei C, Ni C, Song T, Liu Y, Yang X, Zheng Z, Jia Y, Yuan Y, Guan K, Xu Y. The hepatitis B virus X protein disrupts innate immunity by downregulating mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein. J Immunol. 2010;185:1158-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Ehata T, Yokosuka O, Imazeki F, Omata M. Point mutation in precore region of hepatitis B virus: sequential changes from ‘wild’ to ‘mutant’. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:566-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Imamura T, Yokosuka O, Kurihara T, Kanda T, Fukai K, Imazeki F, Saisho H. Distribution of hepatitis B viral genotypes and mutations in the core promoter and precore regions in acute forms of liver disease in patients from Chiba, Japan. Gut. 2003;52:1630-1637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Omata M, Ehata T, Yokosuka O, Hosoda K, Ohto M. Mutations in the precore region of hepatitis B virus DNA in patients with fulminant and severe hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1699-1704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Liang TJ, Hasegawa K, Rimon N, Wands JR, Ben-Porath E. A hepatitis B virus mutant associated with an epidemic of fulminant hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1705-1709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Schaefer E, Koeppen H, Wirth S. Low level virus replication in infants with vertically transmitted fulminant hepatitis and their anti-HBe positive mothers. Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152:581-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bonino F, Rosina F, Rizzetto M, Rizzi R, Chiaberge E, Tardanico R, Callea F, Verme G. Chronic hepatitis in HBsAg carriers with serum HBV-DNA and anti-HBe. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:1268-1273. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Milich DR, Chen MK, Hughes JL, Jones JE. The secreted hepatitis B precore antigen can modulate the immune response to the nucleocapsid: a mechanism for persistence. J Immunol. 1998;160:2013-2021. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Chen MT, Billaud JN, Sällberg M, Guidotti LG, Chisari FV, Jones J, Hughes J, Milich DR. A function of the hepatitis B virus precore protein is to regulate the immune response to the core antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14913-14918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Chen M, Sällberg M, Hughes J, Jones J, Guidotti LG, Chisari FV, Billaud JN, Milich DR. Immune tolerance split between hepatitis B virus precore and core proteins. J Virol. 2005;79:3016-3027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Visvanathan K, Skinner NA, Thompson AJ, Riordan SM, Sozzi V, Edwards R, Rodgers S, Kurtovic J, Chang J, Lewin S. Regulation of Toll-like receptor-2 expression in chronic hepatitis B by the precore protein. Hepatology. 2007;45:102-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 43. | Sells MA, Chen ML, Acs G. Production of hepatitis B virus particles in Hep G2 cells transfected with cloned hepatitis B virus DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1005-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 868] [Cited by in RCA: 939] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Acs G, Sells MA, Purcell RH, Price P, Engle R, Shapiro M, Popper H. Hepatitis B virus produced by transfected Hep G2 cells causes hepatitis in chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4641-4644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kawai S, Yokosuka O, Kanda T, Imazeki F, Maru Y, Saisho H. Quantification of hepatitis C virus by TaqMan PCR: comparison with HCV Amplicor Monitor assay. J Med Virol. 1999;58:121-126. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Wu S, Kanda T, Imazeki F, Nakamoto S, Shirasawa H, Yokosuka O. Nuclear receptor mRNA expression by HBV in human hepatoblastoma cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2011;312:33-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Wendlandt EB, Graff JW, Gioannini TL, McCaffrey AP, Wilson ME. The role of microRNAs miR-200b and miR-200c in TLR4 signaling and NF-κB activation. Innate Immun. 2012;18:846-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Liu X, Zhan Z, Xu L, Ma F, Li D, Guo Z, Li N, Cao X. MicroRNA-148/152 impair innate response and antigen presentation of TLR-triggered dendritic cells by targeting CaMKIIα. J Immunol. 2010;185:7244-7251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Noguchi S, Yamada N, Kumazaki M, Yasui Y, Iwasaki J, Naito S, Akao Y. socs7, a target gene of microRNA-145, regulates interferon-β induction through STAT3 nuclear translocation in bladder cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12481-12486. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Warg LA, Oakes JL, Burton R, Neidermyer AJ, Rutledge HR, Groshong S, Schwartz DA, Yang IV. The role of the E2F1 transcription factor in the innate immune response to systemic LPS. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303:L391-L400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Hu G, Zhou R, Liu J, Gong AY, Eischeid AN, Dittman JW, Chen XM. MicroRNA-98 and let-7 confer cholangiocyte expression of cytokine-inducible Src homology 2-containing protein in response to microbial challenge. J Immunol. 2009;183:1617-1624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Schulte LN, Eulalio A, Mollenkopf HJ, Reinhardt R, Vogel J. Analysis of the host microRNA response to Salmonella uncovers the control of major cytokines by the let-7 family. EMBO J. 2011;30:1977-1989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Chen XM, Splinter PL, O’Hara SP, LaRusso NF. A cellular micro-RNA, let-7i, regulates Toll-like receptor 4 expression and contributes to cholangiocyte immune responses against Cryptosporidium parvum infection. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28929-28938. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Satoh M, Tabuchi T, Minami Y, Takahashi Y, Itoh T, Nakamura M. Expression of let-7i is associated with Toll-like receptor 4 signal in coronary artery disease: effect of statins on let-7i and Toll-like receptor 4 signal. Immunobiology. 2012;217:533-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Lehmann SM, Krüger C, Park B, Derkow K, Rosenberger K, Baumgart J, Trimbuch T, Eom G, Hinz M, Kaul D. An unconventional role for miRNA: let-7 activates Toll-like receptor 7 and causes neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:827-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 605] [Article Influence: 46.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Su C, Hou Z, Zhang C, Tian Z, Zhang J. Ectopic expression of microRNA-155 enhances innate antiviral immunity against HBV infection in human hepatoma cells. Virol J. 2011;8:354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Liu WH, Yeh SH, Chen PJ. Role of microRNAs in hepatitis B virus replication and pathogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1809:678-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Hayes CN, Akamatsu S, Tsuge M, Miki D, Akiyama R, Abe H, Ochi H, Hiraga N, Imamura M, Takahashi S. Hepatitis B virus-specific miRNAs and Argonaute2 play a role in the viral life cycle. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Arataki K, Hayes CN, Akamatsu S, Akiyama R, Abe H, Tsuge M, Miki D, Ochi H, Hiraga N, Imamura M. Circulating microRNA-22 correlates with microRNA-122 and represents viral replication and liver injury in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Med Virol. 2013;85:789-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Ji F, Yang B, Peng X, Ding H, You H, Tien P. Circulating microRNAs in hepatitis B virus-infected patients. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:e242-e251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Cheong JY, Shin HD, Kim YJ, Cho SW. Association of polymorphism in MicroRNA 219-1 with clearance of hepatitis B virus infection. J Med Virol. 2013;85:808-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Jopling CL, Yi M, Lancaster AM, Lemon SM, Sarnow P. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific MicroRNA. Science. 2005;309:1577-1581. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Bhanja Chowdhury J, Shrivastava S, Steele R, Di Bisceglie AM, Ray R, Ray RB. Hepatitis C virus infection modulates expression of interferon stimulatory gene IFITM1 by upregulating miR-130A. J Virol. 2012;86:10221-10225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Sun G, Rossi JJ. MicroRNAs and their potential involvement in HIV infection. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:675-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Shrivastava S, Mukherjee A, Ray RB. Hepatitis C virus infection, microRNA and liver disease progression. World J Hepatol. 2013;5:479-486. [PubMed] |