Published online Nov 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.8085

Revised: June 28, 2013

Accepted: July 30, 2013

Published online: November 28, 2013

Processing time: 219 Days and 0.3 Hours

AIM: To determine the clinical effects and complications of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) for portal hypertension due to cirrhosis.

METHODS: Two hundred and eighty patients with portal hypertension due to cirrhosis who underwent TIPS were retrospectively evaluated. Portal trunk pressure was measured before and after surgery. The changes in hemodynamics and the condition of the stent were assessed by ultrasound and the esophageal and fundic veins observed endoscopically.

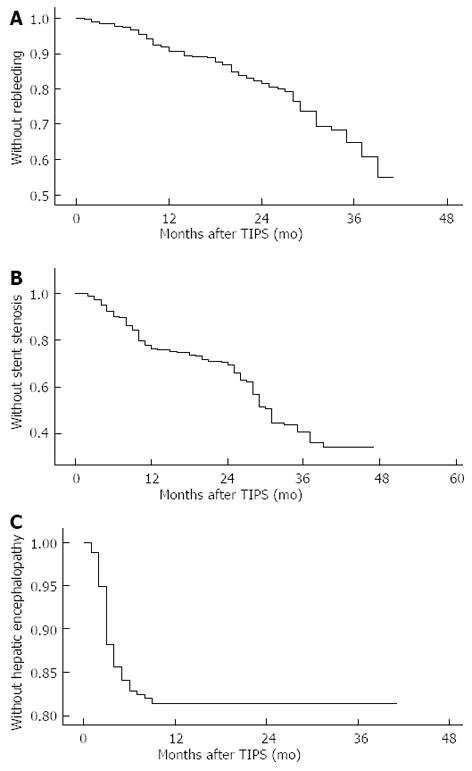

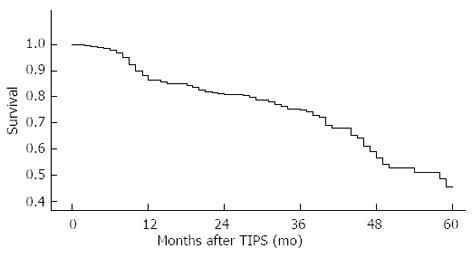

RESULTS: The success rate of TIPS was 99.3%. The portal trunk pressure was 26.8 ± 3.6 cmH2O after surgery and 46.5 ± 3.4 cmH2O before surgery (P < 0.01). The velocity of blood flow in the portal vein increased. The internal diameters of the portal and splenic veins were reduced. The short-term hemostasis rate was 100%. Esophageal varices disappeared completely in 68% of patients and were obviously reduced in 32%. Varices of the stomach fundus disappeared completely in 80% and were obviously reduced in 20% of patients. Ascites disappeared in 62%, were markedly reduced in 24%, but were still apparent in 14% of patients. The total effective rate of ascites reduction was 86%. Hydrothorax completely disappeared in 100% of patients. The incidence of post-operative stent stenosis was 24% at 12 mo and 34% at 24 mo. The incidence of post-operative hepatic encephalopathy was 12% at 3 mo, 17% at 6 mo and 19% at 12 mo. The incidence of post-operative recurrent hemorrhage was 9% at 12 mo, 19% at 24 mo and 35% at 36 mo. The cumulative survival rate was 86% at 12 mo, 81% at 24 mo, 75% at 36 mo, 57% at 48 mo and 45% at 60 mo.

CONCLUSION: TIPS can effectively lower portal hypertension due to cirrhosis. It is significantly effective for hemorrhage of the digestive tract due to rupture of esophageal and fundic veins and for ascites and hydrothorax caused by portal hypertension.

Core tip: This study identified the clinical effects and complications of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) for portal hypertension due to cirrhosis in 280 patients who underwent this procedure at our centre between January 2005 and December 2009. TIPS can effectively lower portal hypertension due to cirrhosis. It is significantly effective for hemorrhage of the digestive tract due to rupture of esophageal and fundic veins and for ascites and hydrothorax caused by portal hypertension.

- Citation: Qin JP, Jiang MD, Tang W, Wu XL, Yao X, Zeng WZ, Xu H, He QW, Gu M. Clinical effects and complications of TIPS for portal hypertension due to cirrhosis: A single center. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(44): 8085-8092

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i44/8085.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.8085

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is an effective procedure for portal hypertension due to cirrhosis and related complications. At the end of the 1980s, Rösch et al[1] and Rössle et al[2] first reported the use of Palmaz, a self-expanding stent. Since then Palmaz had been gradually applied and disseminated in clinical practice. In our centre, TIPS was used, in the initial stage, mainly for the treatment of patients intolerant of surgery, patients with recurrent hemorrhage despite medication and in patients with refractory ascites. As this procedure was developed and improved, it was also used in the treatment of recurrent hemorrhage of the digestive tract due to cirrhosis, hemorrhage after endoscopic ligation and sclerosing therapy, hemorrhage after surgery, portal thrombosis, ascites and hydrothorax due to portal hypertension, hepatorenal syndrome, and emergency hemorrhea. In this study, the significant clinical effects and complications of TIPS are discussed in 280 patients who underwent this procedure at our centre between January 2005 and December 2009.

The clinical data on the outcome of TIPS in 280 patients between January 2005 and December 2009 were retrospectively analyzed. These 280 patients with portal hypertension due to cirrhosis met the criteria of the American Hepatological Association[3,4] for the clinical application of TIPS.

Patients with cirrhotic portal hypertension underwent routine abdominal enhanced computed tomography (CT) scanning and hepatic portal vein CT three-dimensional reconstruction prior to TIPS. During TIPS, after paracentesis from the right hepatic vein or hepatic segment of the inferior vena cava to the branch of the portal vein, direct portography was carried out, then balloon dilatation, followed by stent placement. Portal venous pressure was measured before and after stent placement. Spring wire loops, a gelatine sponge and sclerosing agent were used for blockage of the collateral circulation of esophageal and fundic varices. The stents used were Zilver stents. Specifications of the stents: ZIV 6-80-8 or 10-8.0 (Cook Corporation, Bloomington, IN). Specifications of the balloon: ATB 5-35-8-6.0 or 4.0 (Cook Corporation). Specifications of the spring wire loop: MWCE-35-3-3, 4, 5, 8, 10 (Cook Corporation). Generally, the puncture path was dilated with a balloon of 8 mm inside diameter, and a stent of 8 or 10 mm inside diameter was then positioned.

Anticoagulant therapy was administered in addition to routine expectant treatment. Heparin sodium 12500 IU was administered by in intravenous drip 24-h for 7 d 24 h after surgery, and then oral sodium warfarin tablets for 1 year. Prothrombin time (PT) was maintained for 17-20 s.

All patients were followed up 1 wk and 1 mo after surgery, followed by every 3 mo for 12 mo and then every 6 mo after 12 mo. Each follow-up visit included ultrasonography, liver and renal function tests, blood ammonia, routine blood examination and blood coagulation tests, and symptoms and signs of portal hypertension. Gastroscopy was performed in each patient from the month 1 to the month 3 after surgery and direct portography from the month 9 to the month 12.

All measurement data are presented as mean ± SD. The data before and after surgery were analyzed using the t test. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Stent stenosis, hepatic encephalopathy, recurrent hemorrhage and survival were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method.

All 280 patients had portal hypertension. Of these patients, 220 had severe esophageal varices, 60 had severe esophageal and moderate-severe fundic varices, 42 had a large amount of ascites, 31 had a moderate amount of ascites and 40 had intractable ascites which was complicated by a large right hydrothorax in 4. Table 1 shows the patients’sex, causes of portal hypertension and Child-Pugh grading. Differences between the patients’ sex, age, causes and Child-Pugh grading and their survival rate, incidence of rebleeding, incidence of hepatic encephalopathy and incidence of stent stenosis were not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

| Clinical factor | No. of patients |

| Sex | |

| Male | 223 |

| Female | 57 |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 48.2 ± 13.7 |

| Procedure | |

| Elective | 260 |

| Emergency | 20 |

| Indication for TIPS | |

| Hemorrhage of upper digestive tract | 265 |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 15 |

| Cause | |

| Cirrhosis after hepatitis B virus infection | 168 |

| Cirrhosis after hepatitis C virus infection | 10 |

| Hepatatis B virus infection complicated by schistosomial cirrhosis | 16 |

| Hepatitis B virus infection complicated by alcoholic cirrhosis | 54 |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 24 |

| Unexplained cirrhosis | 8 |

| Child-Pugh grading | |

| A | 60 |

| B | 184 |

| C | 36 |

All 280 patients underwent puncture of the right internal jugular vein. Of these patients, 200 underwent puncture of the right hepatic vein, 80 puncture of the inferior vena cava near the liver, 198 underwent puncture of the right branch of the portal vein and 80 puncture of the left branch and 2 had severe hemorrhage in the abdominal cavity during this procedure (1 died, and the other survived after emergency treatment). The success rate of surgery was 99.3% and the incidence of lethal complications was 0.7%. Embolism caused a collateral circulation in esophageal and fundal varices.

Following the establishment of a portosystemic shunt pathway, liver hemodynamics changed. Portal pressure decreased after surgery, the internal diameters of the portal and splenic veins decreased and the blood velocity in the trunk of the portal vein increased (Table 2).

| Preoperative | Postoperative | P value | |

| Portal venous pressure (cmH2O) | 46.5 ± 3.4 | 26.8 ± 3.6 | < 0.001 |

| Portal venous internal diameter (cm) | 1.68 ± 0.15 | 1.32 ± 0.11 | 0.007 |

| Splenic venous internal diameter (cm) | 1.31 ± 0.05 | 1.12 ± 0.03 | 0.009 |

| Blood velocity in the portal vein (cm/s) | 15.2 ± 4.7 | 49.3 ± 18.5 | < 0.001 |

| Blood velocity in the shunt pathway (cm/s) | 154.0 ± 32.6 |

Liver function was slightly altered after TIPS. No marked changes in alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirubin, and albumin (Alb) before and after surgery were observed. Routine anticoagulant therapy was given postoperatively. PT increased significantly after surgery (Table 3).

| TIPS | ALT | TBIL | Alb | PT |

| (IU/L) | (μmol/L) | (g/L) | (s) | |

| 1 wk before TIPS | 40.78 ± 5.41 | 29.33 ± 5.97 | 32.49 ± 5.14 | 13.43 ± 1.44 |

| 1 mo after TIPS | 42.26 ± 2.32 | 28.45 ± 8.71 | 33.25 ± 4.18 | 17.73 ± 1.83a |

| P value | 0.679 | 0.813 | 0.716 | 0.036 |

The short-term hemostasis rate was 100% when TIPS was used in the treatment of emergency hemorrhage and recurrent hemorrhage unresponsive to medication, endoscopy or surgery. Ascites disappeared completely in 62% of patients, decreased obviously in 24% and remained in 14%. The total effective rate was 86%. Hydrothorax completely disappeared in 100% of patients. Fifteen patients who had hepatorenal syndrome became responsive to diuretic therapy. Ascites completely disappeared in 7 patients and was obviously reduced in 8 after 7-14 d of observation.

Complications occurred during surgery and both short- and long-term postoperative complications were observed (Table 4). The most serious complication was abdominal cavity hemorrhage, which frequently endangered the patient’s life. Short-term severe complications after surgery were hepatic failure, septicemia and abdominal cavity hemorrhage. Intermediate and long-term complications were stent stenosis and hepatic encephalopathy.

| Complication | |

| Intraoperative | |

| Abdominal cavity hemorrhage | 2 (0.7) |

| Puncture of biliary tract | 10 (3.6) |

| Puncture of gallbladder | 5 (1.8) |

| Puncture of hepatic artery | 8 (2.9) |

| Puncture of hepatic capsule | 18 (6.4) |

| Heterotopic embolism | 4 (1.4) |

| Displacement of stent | 6 (2.1) |

| Short-term after TIPS (1 mo) | |

| Abdominal cavity hemorrhage | 2 (0.7) |

| Hepatic failure | 20 (7.2) |

| Hemorrhagic ascites | 7 (2.5) |

| Hemorrhage of digestive tract | 4 (1.4) |

| Septicemia | 3 (1.1) |

| Hemolysis | 8 (2.9) |

| Hyperglycemia | 4 (1.4) |

| Hemobilia | 2 (0.7) |

| Subcapsular hematoma of liver | 3 (1.1) |

| Puffiness of face | 2 (0.7) |

| Long-term after TIPS (> 1 mo) cumulative incidence | |

| Stent abnormality | |

| 12 mo | 24% |

| 24 mo | 34% |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | |

| 3 mo | 14% |

| 6 mo | 18% |

| 12 mo | 19% |

All the 278 patients who underwent TIPS were followed up. Hemorrhage, stent function, hepatic encephalopathy and survival were observed during the follow-up. The incidence of recurring hemorrhage was 9% in 12 mo, 19% in 24 mo and 35% in 36 mo (Figure 1A). The incidence of stent stenosis was 24% in 12 mo and 34% in 24 mo postoperatively (Figure 1B). The incidence of hepatic encephalopathy was 14% in 3 mo, 17% in 6 mo and 19% in 12 mo (Figure 1C). The cumulative survival rate was 86% in 12 mo, 81% in 24 mo, 75% in 36 mo, 57% in 48 mo and 45% in 60 mo (Figure 2). In our center, 3 patients died 1 mo after TIPS, of whom 2 died of hepatic failure and 1 of septicemia.

TIPS is an effective method of treating portal hypertension due to cirrhosis and its complications. Because it is characterized as safe, micro-traumatic, effective and easily repetitive, it has been used more and more widely in clinical practice. Hepatic transplantation has not yet been popularized in China, therefore TIPS is effective for treating portal hypertension due to cirrhosis and its complications, particularly hemorrhage of the digestive tract, and is effective for treating refractory ascites and hydrothorax caused by portal hypertension. It is used mainly in the treatment of approximately 15%-20% of patients with refractory ascites and hemorrhage due to varices that are not responsive to medication or endoscopy. TIPS is used for 99% of cases with these two conditions[5,6]. In addition, TIPS is used for the treatment of hepatic hydrothorax, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatopulmonary syndrome and Budd-Chiari syndrome[7]. In our study, TIPS was also successfully adopted in emergency and portal thrombosis.

In our study, the success rate of TIPS was 99.3%. Once the shunt pathway was established, the portal vein pressure fell from 46.5 ± 3.4 cmH2O before surgery (P < 0.01) to 26.8 ± 3.6 cmH2O after surgery. The instant rate of hemostasis was 100%. These results are consistent with literature reports[8-10] which show that the short-term effective rate of TIPS is 90%-97.4% and the rate of emergency hemorrhage control is 90%-100%. In the present study, the total effective rate of TIPS for ascites was 86% and the rate of elimination of hydrothorax was 100%. These findings are similar to the reported[9] effective rate of 50%-92% for refractory ascites and elimination of ascites in 70%-75% of patients. According to the literature reports[11]: 82% of patients who underwent TIPS had significantly reduced hydrothorax and in 71% hydrothorax was eliminated, however, patients over 60 did not respond well to TIPS. In our study, hydrothorax was eliminated in 4 cases. However, the number of cases was small and the therapeutic effects remain to be determined. Fifteen patients with hepatorenal syndrome became responsive to diuretic therapy after TIPS and their renal functions were obviously improved. Ascites was eliminated in 7 of these patients and was improved in 8. Eight patients were alive after a one-year of follow-up (53%). According to the literature reports[12], renal function was remarkably improved by TIPS in patients with hepatorenal syndrome and the survival rate was 48% after a one-year follow-up, however, only 10% of the patients who did not undergo TIPS lived for three months. These findings suggest that TIPS is an effective method of treating hepatorenal syndrome.

Of the 280 patients in the present study, 2 had abdominal cavity hemorrhage after TIPS. One patient died and the other survived after portal vein repair. Hemorrhage was due to dilation of the sacculus near the bifurcation of the portal vein. The incidence of this severe complication was 0.7%. It is the most severe complication of TIPS in that a patient immediately suffers from hemorrhagic shock and dies. Therefore, the operator should pay close attention to this complication. As reported[13], the incidence of lethal complications related to the procedure was 0.6%-4.2%. The most critical complications after TIPS were worsening of liver function and hepatic encephalopathy. Both were related to a decrease in blood perfusion in the liver due to the establishment of the shunt pathway[14]. In our study, various degrees of hepatic injury occurred in all 280 patients after TIPS, however liver function was gradually restored after approximately 1 mo in most patients. The changes in bilirubin, ALT and Alb were not significantly different. This may be related to our patients having mainly Child-Pugh B and A liver function, few patients with Child-Pugh C liver function (36 patients) and dilation of the path using a balloon of 8 mm inside diameter. The incidence of hepatic failure 1 mo postoperatively was 7.2% (20/278) in our patients, which occurred mainly in emergency and Child-Pugh C TIPS patients. This may be related to poor liver reserve function in some patients and hypoperfusion of the liver due to the artificial shunt and the short supply of hepatic nutrients.

In order to reduce and avoid severe complications of TIPS, the operator is required to be familiar with the anatomy of the portal system. As reported[15,16], the bifurcation of the portal vein is in the liver in about 25.8% of patients, outside the liver in about 48.4% and in the hepatic capsule in about 25.8%. In patients with cirrhosis, the cleavage of the liver is widened and the right trunk and the left horizontal trunk are outside the parenchyma of the liver with bare inferior walls, suggesting that puncture of the bifurcation and peri-bifurcation region is very dangerous. Therefore, the puncture point should be located 2 cm above the bifurcation of the portal vein to reduce or avoid the risk of hemorrhage due to portal vein rupture. In addition, the blood coagulation mechanism is poor in some patients, especially if they have ascites. Hemorrhage will occur if the hepatic capsule is ruptured, and is not easy to stop. Of our patients, 2 (0.7%) had postoperative abdominal cavity hemorrhage and 7 (2.5%) bloody ascites. The bleeding stopped after management.

The intermediate and long-term complications of TIPS are stent abnormality and hepatic encephalopathy. It is reported[10,17] that the rate of stent abnormality (inclusive of stenosis and obstruction) is 17%-50% 6 mo after TIPS and 23%-87% 12 mo after TIPS. The application of a Viatorr stent has improved the condition.

The current criteria[18-20] for the evaluation of stent abnormalities (mainly stenosis) are: (1) the velocity of blood flow is over 200 cm/s or less than 50 cm/s in the shunt path, or the diameter of the shunt path is less than 50%; (2) the velocity of blood flow is less than 20 cm/s in the portal vein; (3) the portosystemic pressure gradient is more than or equal to 16 cmH2O; (4) portal hypertension recurs, i.e., esophagofundic hemorrhage due to varicose vein or ascites not responsive to low salt diet therapy and routine diuretic therapy. Once the stent abnormality is detected by ultrasound, direct portography and repair should be carried out.

The cumulative rate of stent stenosis is 24% in 12 mo and 34% in 24 mo. The currently used Viatorr stent-graft was first adopted in Europe at the end of 1999 and granted approval by the FDA in 2004. The technical success rate is 100%. The first and second patency rates in one year were 76%-84% and 98%-100%[21-23], respectively. In our study, the patency rate in one year was 76%, which was similar to the first patency rate in the report. Explanations for this rate are as follows: puncture was through the inferior vena cava near the liver (80 cases), avoiding stenosis induced by puncture of the liver vein; the shunt was straight and short apart from the left portal branch; attention was paid to the appliance of the puncture path and care was taken care to avoid angulating the stent; and anticoagulant therapy was given after the procedure, which lasted 1 year. PT was maintained for 17-20 s. It is now accepted that stent stenosis[24,25] is related to pseudo-endometrial hyperplasia, the mechanism of which is still unclear but leads to active proliferation of myofibroblasts and the accumulation of extracellular matrix containing collagen. The Viatorr stent-graft has not yet been extensively used, therefore, the prevention of stent stenosis is very important. In our centre a pathological study is now being carried out.

Hepatic encephalopathy is another complication of TIPS. In our study, the incidence of hepatic encephalopathy was 14% in 3 mo and 18% in 6 mo after TIPS. According to the literature[8,10,21,23,26], the incidence of hepatic encephalopathy was 33%-55% after TIPS and 13%-26% after therapeutic endoscopy. International reports[27,28] showed that there was no significant difference in the occurrence of hepatic encephalopathy between the bare and Viatorr stents 10 mm in diameter, and the incidence was 20%-30%. The incidence of hepatic encephalopathy was 5%-10% when Viatorr stents of 8 mm in diameter were used, which supported shunting without hepatic encephalopathy. In our study, the incidence of hepatic encephalopathy was lower than that reported and similar to that of the Viatorr stent and endoscope, which may be related to the selection of patients, puncture paths, stent diameters, etiological treatment and postoperative management. Of the 280 patients, most were graded as Child-Pugh A and B (244/280) with better liver function potential. Cirrhosis was induced mainly by HBV (238/280) and antiviral therapy was given before and after surgery. The patients’ general physical condition was improved before surgery as far as possible. A stent with an appropriate diameter was carefully selected to avoid over shunting. Generally, we chose a balloon of 8 mm inside diameter and a stent of 8 mm or 10 mm inside diameter. For all patients, protein intake was limited 1 wk after surgery, bowel movement was regulated and enema with vinegar ordered to prevent intestinal infection. The mechanism of hepatic encephalopathy[29] involves multiple factors, but is mainly related to a decrease in blood flow and enhancement of the biological availability of enteric toxins.

The rate of recurrent hemorrhage was 9% in 1 year and 19% in 2 years after TIPS in our study. From previous reports[10,17,21,30] the rate was 15% in 1 year and 21% in 2 years after TIPS; and was 48% in 1 year and 52% in 2 years after gastroscopic treatment; and was less than 10% with the Viatorr stent. It was believed that the rate of recurrent hemorrhage was higher in the gastroscope group than in the TIPS group; and was lower in the Viatorr stent group than in the bare stent group. In our study, the rate of recurrent hemorrhage was similar to that of the Viatorr stent. Recurrent hemorrhage was related to stent abnormality. Any cause of stent stenosis or obstruction could lead to portal hypertension again, and the obstructed collateral circulation might reopen or a new collateral circulation could appear, resulting in hemorrhage from esophageal or fundic varices. Once the varicose vein ruptures, recurrent hemorrhage occurs. The maintenance of stent function is important in avoiding this situation. In our research, the rate of stent stenosis was low and the rate of recurrent hemorrhage was also low. In addition, the collateral vein with esophageal and fundic varices due to intraoperative embolism could significantly reduce or delay the occurrence of rebleeding.

Gastroscopy was performed in our patients. The results showed that 68% of patients had complete relief of esophageal varices and 32% had obvious relief. Approximately 80% of patients had complete relief of stomach fundic varices and 20% had obvious relief. This confirmed the effectiveness of TIPS and was an important procedure for recurrent hemorrhage. In our patients, hyperglycemia, puffiness of the face and other rare complications occurred in addition to the complications reported. Hyperglycemia may be explained by the metabolic disorder of glucose in the liver and insulin injection is indicated. The cause of puffiness of the face is unclear, but it gradually disappeared following diuretic therapy.

The cumulative survival rate was 86% at 1 year and 81% at 2 years after TIPS in our patients, which was similar to previously published reports[8,9] that is 64%-87% at 1 year and 56%-71% at 2 years after TIPS. Survival is related to liver function reserve. The survival rate was lower in patients graded as Child-Pugh C than in patients graded as A and B. Our patients were mainly Child-Pugh B, and few patients had Child-Pugh A and B. Statistical analysis showed that the survival rate of the patients was not significantly correlated with their Child-Pugh grading of liver function, which requires further study. There were 15 patients with hepatorenal syndrome in our study, with a death rate of 47% 1 year after TIPS. Three patients died 1 mo postoperatively, of whom 2 died of hepatic failure and 1 of hematosepsis. Our patients mainly developed cirrhosis after hepatitis B virus infection. The etiological treatment is critical in that we found that antiviral therapy and moderate shunting prolonged the survival of patients, especially of those graded as Child-Pugh A and B. These findings remain to be confirmed by future multicenter, randomized and controlled trials.

TIPS is characterized by its effectiveness and few complications. However, stent stenosis and hepatic encephalopathy are still leading factors affecting the intermediate and long-term therapeutic effects. Even though these problems can be solved to a considerable degree by the use of the Viatorr stent, this procedure is not popular in China, and the mechanism of stent stenosis remains to be studied further. Therefore the determination of the therapeutic effects and the association of the shunt pathway with encephalopathy requires further research.

Esophageal and fundic varicose hemorrhage is a critical complication of portal hypertension due to cirrhosis, and often endangers the patient’s life. The clinical effects of routine treatment on hepatic thoracicoabdominal ascites and hepatorenal syndrome are not good. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is an ideal method of treating these complications.

TIPS is one of the most difficult operations in vascular interventional therapy at the present time. A shunt path must be established between the branches of the hepatic veins and portal vein, and at the same time a collateral circulation by embolization in esophageal and fundic varices is necessary to achieve a partial shunt and cutout. TIPS has progressively become the method of choice for treating portal hypertension due to cirrhosis and its complications.

By comparison with the results in the literature, in this study, TIPS improved patient outcome. Portal vein puncture was guided by replacing routine trans-superior mesenteric indirect portal venography with hepatic enhanced computed tomography (CT) scanning and hepatic portal vein CT three-dimensional graphic reconstruction. More cases were treated as the technique was developed. The patients were followed up over a long period, and satisfactory clinical effects were achieved.

As the authors were unable to carry out hepatic transplantation, the complications of cirrhosis were mainly managed clinically, especially varicose hemorrhage and intractable thoracicoabdominal ascites. The effects of the presently used drugs, endoscopes and surgical management are not ideal, however, treatment by TIPS has achieved satisfactory results. With the constant expansion of indications, TIPS will be used more extensively.

TIPS involves the establishment of a shunt path in the liver parenchyma between the two puncture points after paracentesis from the right hepatic vein or hepatic segment of inferior vena cava to the branch of the portal vein, shunting of the portal venous blood flow and lower portal venous pressure, and at the same time causes a collateral circulation by embolization of esophageal and fundic varices and blockage of hemorrhagic blood vessels.

This study comprehensively and systematically evaluated the clinical effects and complications of TIPS for portal hypertension due to cirrhosis, and described how to improve the therapeutic effects of TIPS and the experience in reducing its complications. The improved TIPS is of great clinical significance and favors clinical dissemination.

P-Reviewers: Assy N, Gentilucci UV, Ohkohchi N S-Editor: Zhai HH L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Rösch J, Uchida BT, Putnam JS, Buschman RW, Law RD, Hershey AL. Experimental intrahepatic portacaval anastomosis: use of expandable Gianturco stents. Radiology. 1987;162:481-485. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rössle M, Richter GM, Nöldge G, Palmaz JC, Wenz W, Gerok W. New non-operative treatment for variceal haemorrhage. Lancet. 1989;2:153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Boyer TD, Haskal ZJ. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guidelines: the role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation in the management of portal hypertension. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:615-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Boyer TD, Haskal ZJ. The Role of Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) in the Management of Portal Hypertension: update 2009. Hepatology. 2010;51:306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Azoulay D, Castaing D, Majno P, Saliba F, Ichaï P, Smail A, Delvart V, Danaoui M, Samuel D, Bismuth H. Salvage transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for uncontrolled variceal bleeding in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2001;35:590-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shiffman ML, Jeffers L, Hoofnagle JH, Tralka TS. The role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for treatment of portal hypertension and its complications: a conference sponsored by the National Digestive Diseases Advisory Board. Hepatology. 1995;22:1591-1597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Owen AR, Stanley AJ, Vijayananthan A, Moss JG. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Clin Radiol. 2009;64:664-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sahagun G, Benner KG, Saxon R, Barton RE, Rabkin J, Keller FS, Rosch J. Outcome of 100 patients after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for variceal hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1444-1452. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Rössle M, Siegerstetter V, Huber M, Ochs A. The first decade of the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS): state of the art. Liver. 1998;18:73-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rösch J, Keller FS. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: present status, comparison with endoscopic therapy and shunt surgery, and future prospectives. World J Surg. 2001;25:337-345; discussion 345-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Siegerstetter V, Deibert P, Ochs A, Olschewski M, Blum HE, Rössle M. Treatment of refractory hepatic hydrothorax with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: long-term results in 40 patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:529-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Brensing KA, Textor J, Perz J, Schiedermaier P, Raab P, Strunk H, Klehr HU, Kramer HJ, Spengler U, Schild H. Long term outcome after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in non-transplant cirrhotics with hepatorenal syndrome: a phase II study. Gut. 2000;47:288-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tripathi D, Helmy A, Macbeth K, Balata S, Lui HF, Stanley AJ, Redhead DN, Hayes PC. Ten years’ follow-up of 472 patients following transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt insertion at a single centre. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:9-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Casado M, Bosch J, García-Pagán JC, Bru C, Bañares R, Bandi JC, Escorsell A, Rodríguez-Láiz JM, Gilabert R, Feu F. Clinical events after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: correlation with hemodynamic findings. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1296-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Reference listings in cancer research. Oncol Res. 1993;5:453-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Boyer TD. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: current status. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1700-1710. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Rössle M, Deibert P, Haag K, Ochs A, Olschewski M, Siegerstetter V, Hauenstein KH, Geiger R, Stiepak C, Keller W. Randomised trial of transjugular-intrahepatic-portosystemic shunt versus endoscopy plus propranolol for prevention of variceal rebleeding. Lancet. 1997;349:1043-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tripathi D, Ferguson J, Barkell H, Macbeth K, Ireland H, Redhead DN, Hayes PC. Improved clinical outcome with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt utilizing polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:225-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bureau C, Garcia-Pagan JC, Otal P, Pomier-Layrargues G, Chabbert V, Cortez C, Perreault P, Péron JM, Abraldes JG, Bouchard L, Bilbao JI, Bosch J, Rousseau H, Vinel JP. Improved clinical outcome using polytetrafluoroethylene-coated stents for TIPS: results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:469-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Barrio J, Ripoll C, Bañares R, Echenagusia A, Catalina MV, Camúñez F, Simó G, Santos L. Comparison of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt dysfunction in PTFE-covered stent-grafts versus bare stents. Eur J Radiol. 2005;55:120-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hausegger KA, Karnel F, Georgieva B, Tauss J, Portugaller H, Deutschmann H, Berghold A. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation with the Viatorr expanded polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent-graft. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:239-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vignali C, Bargellini I, Grosso M, Passalacqua G, Maglione F, Pedrazzini F, Filauri P, Niola R, Cioni R, Petruzzi P. TIPS with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent: results of an Italian multicenter study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:472-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rossi P, Salvatori FM, Fanelli F, Bezzi M, Rossi M, Marcelli G, Pepino D, Riggio O, Passariello R. Polytetrafluoroethylene-covered nitinol stent-graft for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation: 3-year experience. Radiology. 2004;231:820-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ducoin H, El-Khoury J, Rousseau H, Barange K, Peron JM, Pierragi MT, Rumeau JL, Pascal JP, Vinel JP, Joffre F. Histopathologic analysis of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 1997;25:1064-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sanyal AJ, Contos MJ, Yager D, Zhu YN, Willey A, Graham MF. Development of pseudointima and stenosis after transjugular intrahepatic portasystemic shunts: characterization of cell phenotype and function. Hepatology. 1998;28:22-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sauer P, Hansmann J, Richter GM, Stremmel W, Stiehl A. Endoscopic variceal ligation plus propranolol vs. transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt: a long-term randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2002;34:690-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Riggio O, Angeloni S, Salvatori FM, De Santis A, Cerini F, Farcomeni A, Attili AF, Merli M. Incidence, natural history, and risk factors of hepatic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt with polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent grafts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2738-2746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Masson S, Mardini HA, Rose JD, Record CO. Hepatic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt insertion: a decade of experience. QJM. 2008;101:493-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hauenstein KH, Haag K, Ochs A, Langer M, Rössle M. The reducing stent: treatment for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt-induced refractory hepatic encephalopathy and liver failure. Radiology. 1995;194:175-179. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Charon JP, Alaeddin FH, Pimpalwar SA, Fay DM, Olliff SP, Jackson RW, Edwards RD, Robertson IR, Rose JD, Moss JG. Results of a retrospective multicenter trial of the Viatorr expanded polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent-graft for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:1219-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |