Published online Oct 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i37.6188

Revised: June 15, 2013

Accepted: July 30, 2013

Published online: October 7, 2013

Processing time: 193 Days and 7.8 Hours

AIM: To determine if esophageal capsule endoscopy (ECE) is an adequate diagnostic alternative to esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in pre-bariatric surgery patients.

METHODS: We conducted a prospective pilot study to assess the diagnostic accuracy of ECE (PillCam ESO2, Given Imaging) vs conventional EGD in pre-bariatric surgery patients. Patients who were scheduled for bariatric surgery and referred for pre-operative EGD were prospectively enrolled. All patients underwent ECE followed by standard EGD. Two experienced gastroenterologists blinded to the patient’s history and the findings of the EGD reviewed the ECE and documented their findings. The gold standard was the findings on EGD.

RESULTS: Ten patients with an average body mass index of 50 kg/m2 were enrolled and completed the study. ECE identified 11 of 14 (79%) positive esophageal/gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) findings and 14 of 17 (82%) combined esophageal and gastric findings identified on EGD. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the findings and no significant difference was found between ECE and EGD (P = 0.64 for esophageal/GEJ and P = 0.66 for combined esophageal and gastric findings respectively). Of the positive esophageal/GEJ findings, ECE failed to identify the following: hiatal hernia in two patients, mild esophagitis in two patients, and mild Schatzki ring in two patients. ECE was able to identify the entire esophagus in 100%, gastric cardia in 0%, gastric body in 100%, gastric antrum in 70%, pylorus in 60%, and duodenum in 0%.

CONCLUSION: There were no significant differences in the likelihood of identifying a positive finding using ECE compared with EGD in preoperative evaluation of bariatric patients.

Core tip: This is the first prospective study that shows in pre-bariatric patients, capsule endoscopy can be used to identify positive esophageal disorders when compared to a sedated esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Further studies are needed to help define the role of esophageal capsule endoscopy as a tool for pre-operative evaluation.

- Citation: Shah A, Boettcher E, Fahmy M, Savides T, Horgan S, Jacobsen GR, Sandler BJ, Sedrak M, Kalmaz D. Screening pre-bariatric surgery patients for esophageal disease with esophageal capsule endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(37): 6188-6192

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i37/6188.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i37.6188

In patients with morbid obesity, surgery is a treatment option associated with good medium and long-term results with procedures such as gastric banding, sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and biliopancreatic diversion[1]. These operations can be performed laparoscopically in most obesity centers[2-4]. Preoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is useful to detect pathological findings that might preclude or delay bariatric surgery[5].

Patients referred for bariatric surgery often have co-morbidities including obstructive sleep apnea, arterial hypertension, coronary heart disease or diabetes mellitus which puts them at risk for any procedure that involves conscious sedation. The risk of EGD in these patients includes aspiration, hypoxemia, hypoventilation, airway obstruction, vasovagal episodes, and arrhythmias. Esophageal capsule endoscopy (ECE) offers a less invasive diagnostic alternative in evaluating diseases of the esophagus. ECE does not require sedation and is therefore better tolerated by patients. Several studies have shown that ECE is an adequate alternative diagnostic method for esophageal variceal screening and diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus in patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux[6-8]. Delvaux et al[9] concluded that capsule endoscopy showed a moderate sensitivity and specificity in detecting esophageal diseases such as esophagitis, hiatal hernias, varices and Barrett’s esophagus. They determined the overall positive predictive value of capsule endoscopy was 80%. In this study we aim to determine if capsule endoscopy is adequate in identifying specific esophageal and gastric pathology for patients undergoing bariatric surgery as compared to EGD.

This was a prospective pilot study. Patients from 2010 to 2012 who were scheduled to undergo bariatric surgery at University of California San Diego Medical Center and referred for pre-operative EGD were prospectively enrolled to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the ECE (PillCam ESO2, Given Imaging) vs conventional EGD. A total of ten patients were enrolled in the study. Patients were enrolled after Human Subjects Research Protection Committee approved consent was obtained. All patients underwent ECE followed by standard EGD performed under moderate sedation with fentanyl and versed All patients underwent ECE followed by standard EGD performed by a single endoscopist that was video recorded. Demographic data was collected on each patient including age, sex, weight in kilograms (kg), and body mass index (BMI) per patient’s medical chart. Co-morbidities on each patient were documented including obstructive sleep apnea, coronary artery disease hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Two experienced gastroenterologists reviewed the ECE and EGD videos and documented their findings. Both gastroenterologists were blinded to patients’ history. Findings on ECE were than compared with the findings on EGD. Findings were categorical variables where 0 represented a normal finding and 1 represented an abnormal finding. Abnormal findings included esophagitis, Schatzki ring, and hiatal hernia. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the findings between the two modalities with the findings on the EGD considered the gold standard.

Table 1 provides baseline demographic information and co-morbidities on each patient. The mean age was 46.2 years with the majority of patients being female (6/10). The average BMI was 50.12 kg/m2 and average weight of 141.85 kg. Eight out of ten patients and nine out of ten patients suffered from suffered from obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension respectively. Forty percent of patients suffered from diabetes and 30% of patients had a diagnosis of NAFLD. Two out of ten patients had chronic kidney disease with a glomerular filtration rate of 55 and 48 mL/min/1.73 sqm.

| Result | Value |

| Characteristics | |

| Mean age (yr) (median) | 46.2 (46) |

| Female | 6 (60) |

| Mean body mass index (kg/m2) (median) | 50.12 (48.1) |

| Weight (kg) (median) | 141.85 (139.9) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 8 (80) |

| Coronary artery disease | 1 (10) |

| Hypertension | 9 (90) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (40) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2 (20) |

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | 3 (30) |

| Visualization | |

| Mean esophageal transit time (min) (median) | 3.997 (3.997) |

| Esophagus | 10 (100) |

| Gastroesophageal junction | 10 (100) |

| Gastric cardia | 0 (0) |

| Gastric body | 10 (100) |

| Gastric antrum | 7 (70) |

| Pylorus | 6 (60) |

| Duodenum | 0 (0) |

Visualization of the esophagus, GE junction, and gastric body were seen 100% of the time on ECE. The antrum and pylorus were identified 70% and 60% of the time respectively. The gastric cardia and the duodenum were not able to be identified on any capsule endoscopies. The majority of the capsules (9/10) were retained in the stomach (Table 1).

Esophageal findings on EGD included Schatzki ring, hiatal hernia and esophagitis. Two patients were noted to have gastric findings. One patient was found to have mild gastropathy and the other patient was described as having a watermelon stomach at the pylorus.

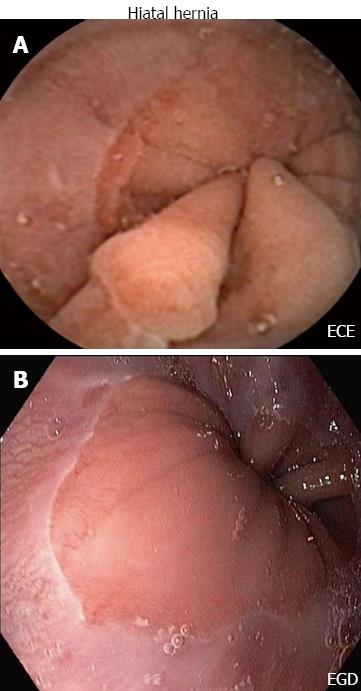

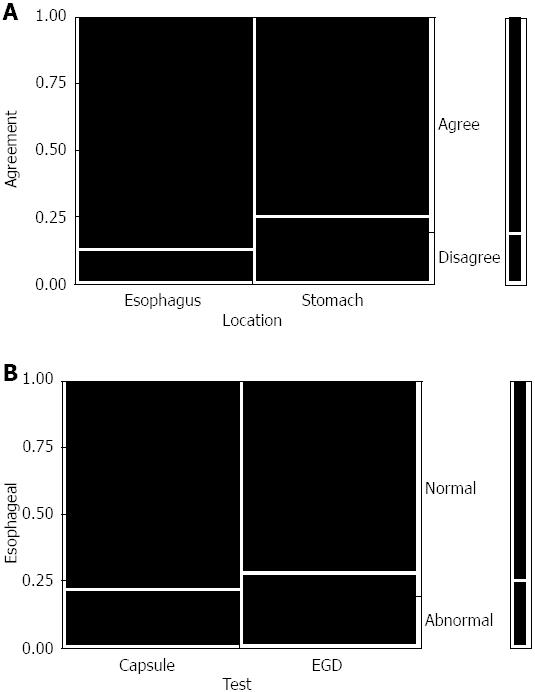

ECE identified 11 of 14 (79%) positive esophageal/gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) findings and 14 of 17 (82%) combined esophageal and gastric findings identified on EGD. Correctly identified abnormal findings on ECE as seen on EGD in the esophagus included hiatal hernia in seven out of ten patients (Figure 1), Schatzki ring in one out of three patients and felinization rings were correctly identified in one patient on both ECE and EGD. Gastric findings seen on ECE as well as EGD included gastropathy in the body of the stomach in three out of three patients. Erosions were correctly identified on ECE and EGD in one patient. There was a trend toward agreement among ECE and EGD findings in the esophagus vs stomach (35/40 findings in agreement in the esophagus vs 30/40 findings in agreement in the stomach) (Figure 2A).

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the findings and no significant difference was found between ECE and EGD (P = 0.64 for esophageal/GEJ and P = 0.66 for combined esophageal and gastric findings respectively) (Figure 2B). Of the positive esophageal/GEJ findings, ECE failed to identify the following: hiatal hernia in two patients, mild esophagitis in two patients, and mild Schatzki ring in two patients. Conversely, ECE identified a Schatzki ring in one patient, an irregular Z-line in another patient, and a hiatal hernia in a third patient not identified on EGD. There were no adverse events related to ECE.

Bariatric surgery is increasingly performed to treat morbid obesity and its complications. Pre-operative EGD can help identify useful pathology that can negatively influence post-operative outcomes. However EGD is an invasive procedure requiring the use of conscious sedation that can carry risks of cardiopulmonary complications, hypoxemia, aspiration and cardiac arrhythmias[10-13]. Quine et al[10] showed in a prospective study of 14149 upper endoscopies that 31 patients experienced cardiopulmonary complications related to moderate sedation. Similar studies have shown the rate of cardiopulmonary complications to range from 1.3 per thousand to 5.4 per thousand[11,14]. Sharma et al[15] showed that the risk of developing unplanned cardiopulmonary events following upper endoscopy was 0.6%. Multiple studies have determined that the risks of moderate sedation in patients undergoing endoscopy increase with co-morbidities such as advanced age, obstructive sleep apnea, underlying heart disease, and obesity[10-12,14,16]. Sharma et al[15] found that an increased American Society of Anesthesiologists classification (ASA class score) was attributed to an increase risk of developing cardiopulmonary complications. Odds ratio ranged from 1.1 with an ASA II score to 1.8 with ASA class III and 7.4 with class V. Many bariatric surgery patients will generally have higher ASA scores.

Endoscopic capsule was initially approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2001 for evaluation of the small bowel. It is increasingly being used for the evaluation of obscure GI bleeding, Crohns’ disease, and suspected small bowel tumors[17-21]. Several studies have shown that capsule endoscopy can be used to identify esophageal disorders such as Barrett’s esophagus/esophagitis, hiatal hernia, and esophageal varices[22-26].

Our study shows that in pre-bariatric patients, capsule endoscopy can be used to identify positive esophageal disorders when compared to a sedated EGD. Capsule endoscopy was correctly able to identify hiatal hernias, Schatzki rings and esophagitis when compared with EGD. However in our study ECE failed to identify gastric pathology the majority of the time. The gastric cardia was not visualized during ECE and the gastric antrum and pylorus were identified 30% and 40% of the time respectively. The duodenum also could not be correctly identified by ECE due to the short capsule recording time of 20 min.

Esophageal findings seen on ECE but not noted on EGD included a Schatzki ring in one patient, an irregular Z-line in another patient, and a hiatal hernia in a third patient. This might be explained by changes in body position between the upright ECE and left lateral decubitus EGD.

Further limitations of this pilot study include a small patient size. Only ten patients were enrolled in the trial. Despite this, results trended towards no significant difference in the likelihood of identifying a positive finding using ECE compared with EGD.

In conclusion, this is the first study to suggest that ECE may be a safer alternative than sedated EGD for evaluation of esophageal disorders prior to bariatric surgery. However ECE cannot consistently evaluate for gastric or duodenal pathology. Further studies are needed to help define the role of ECE as a tool for pre-operative evaluation.

In patients with morbid obesity, bariatric surgery is a treatment option associated with good medium and long-term results. Prior to surgery, many patients undergo an endoscopic examination to determine if they have any pathology to prevent or delay them from undergoing bariatric surgery. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) however is an invasive procedure which comes with risks including the risk of sedation associated with morbidly obese patients. Small bowel capsule endoscopy has been used to identify pathology in the small bowel for years. Esophageal capsule endoscopy (ECE) uses the same technology to examine the esophagus and stomach. Several studies have shown that ECE is able to identify pathology and anatomic variations in the esophagus and stomach, and can be performed without the risks of moderate sedation. No studies to date have been done to determine whether capsule endoscopy is equivalent to EGD in screening pre-bariatric surgery patients.

Small bowel capsule endoscopy was developed as a means to non-invasively examine the small bowel for pathology. ECE was subsequently developed and food and drug administration approved using the same technology to examine the esophagus and stomach. There have been several studies to suggest that ECE is comparable to EGD in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal disorders such as Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal varices.

Small bowel capsule endoscopy is a useful tool to non-invasively examine the small bowel. ECE uses the same technology to examine the esophagus and stomach. Recent studies have shown that ECE is comparable EGD in diagnosing esophageal pathology such as esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal varices as well as stomach pathology such as gastric cancers. However ECE has never been compared to EGD in pre-screening patients for pathology which may preclude them from bariatric surgery. This study is the first study to date to compare the two in this patient population.

The study results indicate that ECE may be a safer alternative than sedated EGD for evaluation of esophageal disorders prior to bariatric surgery, but cannot consistently evaluate for gastric or duodenal pathology. Further studies are needed to help define the role of ECE as a tool for pre-operative evaluation.

Bariatric surgery: Surgery is performed on the stomach and/or intestines in order to facilitate weight loss in obese patients. This could be achieved either through restrictive alone or both restrictive and malabsorptive mechanisms. EGD: An imaging test that involves visually examining the lining of the esophagus, stomach, and upper duodenum with a flexible fiberoptic endoscope; ECE: A small camera inside a capsule shaped and sized like a pill which is used to take video images of the digestive tract to help in evaluation of symptoms such as gastrointestinal bleeding or abdominal pain; Moderate sedation: Drug induced consciousness (typically carried out with a combination of a narcotic such as fentanyl and benzodiazepine such as midazolam) during which patients respond purposefully to verbal commands, either alone or by light tactile stimulation. No interventions are needed to maintain a patent airway, patient is able to spontaneously breathe during moderate sedation. Used in a wide variety of medical procedures.

The results suggest that ECE may be a safer alternative than sedated EGD for evaluation of esophageal disorders prior to bariatric surgery. The paper would be desirable to specify

P- Reviewer Herrerias-Gutierrez JM S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Ma S

| 1. | Brolin RE. Bariatric surgery and long-term control of morbid obesity. JAMA. 2002;288:2793-2796. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kueper MA, Kramer KM, Kirschniak A, Königsrainer A, Pointner R, Granderath FA. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: standardized technique of a potential stand-alone bariatric procedure in morbidly obese patients. World J Surg. 2008;32:1462-1465. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Moy J, Pomp A, Dakin G, Parikh M, Gagner M. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. Am J Surg. 2008;196:e56-e59. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Tice JA, Karliner L, Walsh J, Petersen AJ, Feldman MD. Gastric banding or bypass? A systematic review comparing the two most popular bariatric procedures. Am J Med. 2008;121:885-893. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Anderson MA, Gan SI, Fanelli RD, Baron TH, Banerjee S, Cash BD, Dominitz JA, Harrison ME, Ikenberry SO, Jagannath SB. Role of endoscopy in the bariatric surgery patient. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1-10. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Eliakim R, Sharma VK, Yassin K, Adler SN, Jacob H, Cave DR, Sachdev R, Mitty RD, Hartmann D, Schilling D. A prospective study of the diagnostic accuracy of PillCam ESO esophageal capsule endoscopy versus conventional upper endoscopy in patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux diseases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:572-578. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Lin OS, Schembre DB, Mergener K, Spaulding W, Lomah N, Ayub K, Brandabur JJ, Bredfeldt J, Drennan F, Gluck M. Blinded comparison of esophageal capsule endoscopy versus conventional endoscopy for a diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus in patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:577-583. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Lu Y, Gao R, Liao Z, Hu LH, Li ZS. Meta-analysis of capsule endoscopy in patients diagnosed or suspected with esophageal varices. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1254-1258. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Delvaux M, Papanikolaou IS, Fassler I, Pohl H, Voderholzer W, Rösch T, Gay G. Esophageal capsule endoscopy in patients with suspected esophageal disease: double blinded comparison with esophagogastroduodenoscopy and assessment of interobserver variability. Endoscopy. 2008;40:16-22. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Quine MA, Bell GD, McCloy RF, Charlton JE, Devlin HB, Hopkins A. Prospective audit of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in two regions of England: safety, staffing, and sedation methods. Gut. 1995;36:462-467. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Arrowsmith JB, Gerstman BB, Fleischer DE, Benjamin SB. Results from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy/U.S. Food and Drug Administration collaborative study on complication rates and drug use during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:421-427. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Lieberman DA, Wuerker CK, Katon RM. Cardiopulmonary risk of esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Role of endoscope diameter and systemic sedation. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:468-472. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Yen D, Hu SC, Chen LS, Liu K, Kao WF, Tsai J, Chern CH, Lee CH. Arterial oxygen desaturation during emergent nonsedated upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15:644-647. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Silvis SE, Nebel O, Rogers G, Sugawa C, Mandelstam P. Endoscopic complications. Results of the 1974 American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Survey. JAMA. 1976;235:928-930. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sharma VK, Nguyen CC, Crowell MD, Lieberman DA, de Garmo P, Fleischer DE. A national study of cardiopulmonary unplanned events after GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:27-34. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Barkin JS, Krieger B, Blinder M, Bosch-Blinder L, Goldberg RI, Phillips RS. Oxygen desaturation and changes in breathing pattern in patients undergoing colonoscopy and gastroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989;35:526-530. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Adler DG, Knipschield M, Gostout C. A prospective comparison of capsule endoscopy and push enteroscopy in patients with GI bleeding of obscure origin. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:492-498. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Fireman Z, Mahajna E, Broide E, Shapiro M, Fich L, Sternberg A, Kopelman Y, Scapa E. Diagnosing small bowel Crohn’s disease with wireless capsule endoscopy. Gut. 2003;52:390-392. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Cobrin GM, Pittman RH, Lewis BS. Increased diagnostic yield of small bowel tumors with capsule endoscopy. Cancer. 2006;107:22-27. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Rossini FP, De Franchis R. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:643-653. [PubMed] |

| 21. | de Leusse A, Vahedi K, Edery J, Tiah D, Fery-Lemonnier E, Cellier C, Bouhnik Y, Jian R. Capsule endoscopy or push enteroscopy for first-line exploration of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding? Gastroenterology. 2007;132:855-862; quiz 1164-1165. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Galmiche JP, Sacher-Huvelin S, Coron E, Cholet F, Soussan EB, Sébille V, Filoche B, d’Abrigeon G, Antonietti M, Robaszkiewicz M. Screening for esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus with wireless esophageal capsule endoscopy: a multicenter prospective trial in patients with reflux symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:538-545. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Borobio E, Fernández-Urién I, Elizalde I, Jiménez Pérez FJ. Hiatal hernia and lesions of gastroesophageal reflux disease diagnosed by capsule endoscopy. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2009;101:355-356. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Ahn D, Guturu P. Meta-analysis of capsule endoscopy in patients diagnosed or suspected with esophageal varices. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:785-786. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Sánchez-Yagüe A, Caunedo-Alvarez A, García-Montes JM, Romero-Vázquez J, Pellicer-Bautista FJ, Herrerías-Gutiérrez JM. Esophageal capsule endoscopy in patients refusing conventional endoscopy for the study of suspected esophageal pathology. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:977-983. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Bhardwaj A, Hollenbeak CS, Pooran N, Mathew A. A meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of esophageal capsule endoscopy for Barrett’s esophagus in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1533-1539. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |