Published online May 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i17.2691

Revised: January 29, 2013

Accepted: February 5, 2013

Published online: May 7, 2013

Processing time: 188 Days and 5.6 Hours

AIM: To assess whether schistosomiasis coinfection with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) influences hepatic fibrosis and pegylated-interferon/ribavirin (PEG-IFN/RIB) therapy response.

METHODS: This study was designed as a retrospective analysis of 3596 chronic HCV patients enrolled in the Egyptian National Program for HCV treatment with PEG-IFN/RIB. All patients underwent liver biopsy and anti-schistosomal antibodies testing prior to HCV treatment. The serology results were used to categorize the patients into group A (positive schistosomal serology) or group B (negative schistosomal serology). Patients in group A were given oral antischistosomal treatment (praziquantel, single dose) at four weeks prior to PEG-IFN/RIB. All patients received a 48-wk course of PEG-IFN (PEG-IFNα2a or PEG-IFNα2b)/RIB therapy. Clinical and laboratory follow-up examinations were carried out for 24 wk after cessation of therapy (to week 72). Correlations of positive schistosomal serology with fibrosis and treatment response were assessed by multiple regression analysis.

RESULTS: Schistosomal antibody was positive in 27.3% of patients (15.9% females and 84.1% males). The patients in group A were older (P = 0.008) and had a higher proportion of males (P = 0.002) than the patients in group B. There was no significant association between fibrosis stage and positive schistosomal serology (P = 0.703). Early virological response was achieved in significantly more patients in group B than in group A (89.4% vs 86.5%, P = 0.015). However, significantly more patients in group A experienced breakthrough at week 24 than patients in group B (36.3% vs 32.3%, P = 0.024). End of treatment response was achieved in more patients in group B than in group A (62.0% vs 59.1%) but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.108). Sustained virological response occurred in significantly more patients in group B than in group A (37.6% vs 27.7%, P = 0.000). Multivariate logistic regression analysis of patient data at treatment weeks 48 and 72 showed that positive schistosomal serology was associated with failure of response to treatment at week 48 (OR = 1.3, P = 0.02) and at week 72 (OR = 1.7, P < 0.01).

CONCLUSION: Positive schistosomal serology has no effect on fibrosis staging but is significantly associated with failure of response to HCV treatment despite antischistosomal therapy.

Core tip: Both hepatitis C virus (HCV) and schistosomiasis are highly endemic in Egypt and coinfection is frequently encountered. The effect of such coinfection on hepatic fibrosis and response to pegylated-interferon and ribavirin therapy (PEG-IFN/RIB) remains unclear. Our study aimed to assess the impact of schistosomiasis on hepatic fibrosis and response to PEG-IFN/RIB therapy in chronic HCV Egyptian patients. Antischistosomal antibody was positive in 27.3% of 3596 chronic HCV patients. Findings suggest positive schistosomal serology has no effect on fibrosis stage but is significantly associated with failure of response to HCV treatment despite antischistosomal therapy.

- Citation: Abdel-Rahman M, El-Sayed M, El Raziky M, Elsharkawy A, El-Akel W, Ghoneim H, Khattab H, Esmat G. Coinfection with hepatitis C virus and schistosomiasis: Fibrosis and treatment response. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(17): 2691-2696

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i17/2691.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i17.2691

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major public health problem and a leading cause of chronic liver disease[1]. In fact, Egypt has the largest epidemic of HCV in the world with an overall serum positive prevalence of 14.7% as reported by the Egyptian demographic health survey[2]. It also is a major cause of liver fibrosis, which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality[3].

Schistosomiasis is also of significant concern as it is endemic in Egypt[4,5]. Schistosoma haematobium is endemic in Upper Egypt (7.8% prevalence), while Schistosoma mansoni has greater prevalence in Lower Egypt (36.4%)[6]. The presence of both HCV and Schistosoma spp. is of significant concern as patients with coinfections have been shown to have higher HCV RNA titers, increased histological activity, greater incidence of cirrhosis/hepatocellular carcinoma, and higher mortality rates than patients suffering from single infections[7]. In addition, patients diagnosed with hepatosplenic schistosomiasis have increased opportunities for additional infections and medical abnormalities. These may include up to a 10-fold opportunity for coinfection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) (compared to healthy counterparts), chronic hepatitis on liver biopsy, persistent antigenemia, and increased frequency of liver failure[8].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of schistosomiasis on hepatic fibrosis and on response to pegylated-interferon combined with ribavirin (PEG-IFN/RIB) therapy in Egyptian patients with chronic HCV.

This retrospective study included 3596 Egyptian patients with chronic HCV treated with PEG-IFN/RIB at Cairo-Fatemic Hospital (Cairo, Egypt). Study enrollment inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1.

| Inclusion criteria |

| Age ≥ 18 yr and ≤ 60 yr |

| Positive HCV antibodies and detectable HCV RNA by PCR |

| Positive liver biopsy for chronic hepatitis with F1 METAVIR score and elevated liver enzymes or F2/F3 METAVIR score |

| Naïve to treatment with PEG-IFN and RIB |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen negativity |

| Normal complete blood count, normal thyroid function, prothrombin concentration ≥ 60%, normal bilirubin, α-fetoprotein < 100 (ng/mL) and antinuclear antibody titer < 1/160 |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Serious co-morbid conditions such as severe arterial hypertension, heart failure, significant coronary heart disease, poorly controlled diabetes (hemoglobin A1C > 8.5%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Major uncontrolled depressive illness |

| Solid transplant organ (renal, heart, or lung) |

| Untreated thyroid disease |

| History of previous anti-HCV therapy |

| Body mass index (BMI) > 35 kg/m² |

| Known human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection |

| Hypersensitivity to one of the two drugs (PEG-IFN, RIB) |

| Concomitant liver disease other than hepatitis C (chronic hepatitis B, autoimmune hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, hemochromatosis, α-1 antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson’s disease) |

| Liver biopsy showing severe steatosis (> 66%) and steatohepatitis, decompensated cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma or METAVIR score F4 |

All patients received PEG-IFNα2a (180 μg/wk dose) or PEG-IFNα2b (1.5 μg/kg/wk dose) via subcutaneous injection and oral RIB (800-1200 mg/d) for 48 wk as genotype 4 causes approximately 90% of HCV infections in Egypt[9]. Patients were followed for 24 wk after cessation of therapy (to week 72).

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Ministry of Health (Cairo, Egypt), and all patients consented to blood sampling and data usage in future research. Anti-schistosomal antibody testing was completed for all patients. Patients were stratified according to their schistosomal serological status; group A, HCV patients with positive schistosomal serology; group B, HCV patients with negative schistosomal serology. Study participants with positive schistosomal serology were given praziquantel (PZQ) therapy (oral, 40 mg/kg, single dose) at four weeks prior to initiation of the PEG-IFN/RIB therapy. Liver biopsies were performed for all patients to determine the grade of necroinflammation and stage of fibrosis (Table 2) (based on the METAVIR scoring system[10]).

| Feature | |

| Grade A0 | No histologic necroinflammatory activity |

| Grade A1 | Mild activity |

| Grade A2 | Moderate activity |

| Grade A3 | Severe activity |

| Stage F0 | No fibrosis |

| Stage F1 | Portal fibrosis without septa |

| Stage F2 | Portal fibrosis with rare septa |

| Stage F3 | Numerous septa without cirrhosis |

| Stage F4 | Cirrhosis |

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction was used to detect HCV RNA (detection limit ≥ 50 IU/mL) at baseline and weeks 12, 24, 48 and 72 after initiation of anti-viral therapy. Clinical and laboratory follow-up examinations were carried out to identify the presence of adverse side effects and treatment response. A total of 845 patients were lost to follow-up, so that 2751 participants completed the follow-up to week 72. Patients with early virologic response (EVR) continued follow-up to identify subsequent non-responders. Patients with detectable HCV-RNA at week 24 or those with less than 2 log decrease in viral load at week 12 were designated as treatment failure. HCV therapy was discontinued prematurely in those patients.

Quantitative data were described by averaging and calculating the SD. Intergroup differences were assessed by the Student’s t-test. χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used for comparisons when appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression was performed with failure of treatment set as the dependent variable. In all tests, a P-value of < 0.05 was considered as the threshold for significance.

No statistically significant differences were found in the baseline characteristics of the two groups of patients, with the exceptions of age and sex (Table 3). HCV patients with positive schistosomal serology were older than the negative schistosomal group (P = 0.008) and showed a higher rate of males (P = 0.002). Of the 27.3% of the patients with positive schistosomal serology, 15.9% were females and 84.1% were males.

| Schisto + ve (n = 983) | Schisto - ve (n = 2613) | P value | |

| Age | 42.59 ± 9.21 | 41.62 ± 9.81 | 0.008 |

| Albumin (ref.: 3.5-5.5 mg/dL) | 4.20 ± 0.47 | 4.20 ± 0.47 | 0.251 |

| AST (ref.: 40 IU/L) | 55.91 ± 33.91 | 57.07 ± 46.00 | 0.412 |

| ALT (ref.: 40 IU/L) | 63.19 ± 41.68 | 63.38 ± 43.30 | 0.908 |

| HCV RNA, IU/mL | 1.4 × 106± 6.9 × 106 | 9.5 × 105± 7 × 106 | 0.083 |

| BMI | 28.12 ± 4.09 | 28.27 ± 4.4 | 0.387 |

| Male/female | 5.3/1 | 3.88/1 | 0.002 |

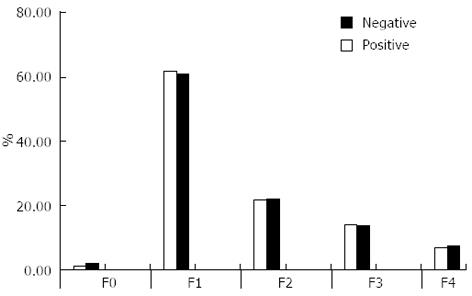

There were no significant differences between groups regarding fibrosis staging (Figure 1) or end of treatment response (ETR) (Table 4). However, the EVR and virological response at week 24 were significantly higher in patients with negative schistosomal serology (P = 0.015 and P = 0.024, respectively).

| Anti-schisto antibody | P value | |||

| Negative | Positive | Total | ||

| (n = 2613) | (n = 983) | (n = 3596) | ||

| Responders at week 12 (EVR) | 2335 (89.4) | 850 (86.5) | 3185 (88.6) | 0.015 |

| Responders at week 24 | 1768 (67.7) | 626 (63.7) | 2394 (66.6) | 0.024 |

| Responders at week 48 (ETR) | 1621 (62.0) | 581 (59.1) | 2202 (61.2) | 0.108 |

Of the 2751 patients that were followed-up to week 72, those with negative schistosomal serology had achieved a higher sustained virological response (SVR) than the other group (37.6% vs 27.7%, P = 0.000).

Multivariate logistic regression analyses indicated that patients with positive schistosomal serology were more likely to fail treatment (OR = 1.3, P = 0.02) at week 48 and (OR = 1.7, P < 0.01) at week 72 (Table 5).

| Factors | OR | P value | 95%CI | |

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Week 48 | ||||

| Age of > 50 yr | 1.15 | 0.245 | 0.91 | 1.50 |

| Female | 0.65 | 0.000 | 0.51 | 0.80 |

| Viremia, > 600 × 103 IU/mL | 1.78 | 0.000 | 1.41 | 2.30 |

| IFNα2b | 1.21 | 0.050 | 1.01 | 1.50 |

| Activity, A2, A3 | 0.68 | 0.001 | 0.54 | 0.90 |

| Fibrosis, > F2 | 1.69 | 0.000 | 1.35 | 2.10 |

| BMI, > 30 kg/m2 | 0.86 | 0.009 | 0.76 | 0.96 |

| Positive schisto status | 1.29 | 0.015 | 1.10 | 1.60 |

| Week 72 | ||||

| Age of > 50 yr | 1.0 | 0.990 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

| Female | 0.7 | 0.006 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Viremia, > 600 × 103 IU/mL | 1.6 | 0.001 | 1.2 | 2.2 |

| Activity, A2, A3 | 0.5 | < 0.01 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Fibrosis, > F2 | 1.9 | < 0.01 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| Positive schisto status | 1.7 | < 0.01 | 1.3 | 2.1 |

This study was undertaken to determine a correlation between HCV and schistosomiasis infection in relation to hepatic fibrosis stages and antiviral treatment response.

Our findings showed a correlation of positive schistosomal serology in reference to sex, with the predominance involving males. HCV patients with positive schistosomal serology were also found to be older than those with negative serology. This finding is suspected to be due to the reservoir of HCV infection in Egypt, for which intravenously administered tartar emetic was used as a primary treatment[11].

While this study showed no significant difference between the two groups in terms of fibrosis staging, other studies report HCV/schistosomiasis coinfected patients have more rapid progression of hepatic fibrosis than those with HCV monoinfection[12], as evidenced by increased fibrosis scores for the liver biopsies taken at 96.0 ± 4.6 mo of follow-up. Moreover, another study demonstrated that serum transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels are higher in coinfected groups[13].

Ahmad et al[14] showed that schistosomiasis coinfection with HCV and/or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis had no significant impact on fibrosis stage. Results involving differences in fibrosis stages may be explained by several factors. Genetic predisposition may play a role, whereby only a minority of the individuals infected with Schistosoma mansoni may develop hepatic fibrosis or be more sensitive to infection(s). Moreover, frequency of exposure is directly correlated with the presence and amount of fibrosis[15]. In addition, several clinical and pathological studies have shown that schistosomal hepatopathy is a reversible condition and that resolution of the schistosomiasis disease is accompanied by subsequent fibrosis resorption[16,17].

Moreover, HCV patients with evidence of coinfection or previous exposure to schistosomiasis received oral antischistosomal treatment of PZQ prior to starting the anti-viral therapy. PZQ is believed to exert antifibrotic effects by affecting (decreasing) activation of hepatic stellate cells through inhibition of profibrotic gene expression[18]. Morcos et al[19] demonstrated that PZQ treatment could induce resolution of schistosoma-induced pathology, showing partial reversal of liver fibrosis in Schistosoma mansoni infected mice. Improvements and/or resolutions of schistosomal-induced periportal thickening/fibrosis in PZQ treated models have also been demonstrated by Berhe et al[20] and Frenzel et al[21]. It is theorized that the beneficial effects are likely related to the clearance of schistosomal worms and subsequent reduction of egg deposition.

Other limiting issues for the use of liver biopsy as a clinical tool for assessing fibrosis in schistosomiasis include ethical considerations and the risk of sampling errors, which may be especially evident for small-volume biopsies[22].

In our current study, the EVR, virological response at week 24, and SVR were significantly higher in patients with negative schistosomal serology. This finding may be attributed to coinfected patients with a down-regulated immune response to HCV leading to reduced IFNγ, interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-10 secreted by HCV-specific T cells. Early reports by Kamal et al[23] using standard IFN in the treatment of chronic HCV patients reported that Egyptian patients with coinfections have higher HCV RNA titers, more advanced liver disease, more hepatic complications and greater mortality rates than those infected with HCV alone.

In light of the previous real time PCR findings from Bahgat et al[24], soluble egg antigen (SEA) should be considered as a potential stimulatory factor for HCV RNA that may have influenced the early detection of HCV RNA as SEA can stimulate viral replication. The higher morbidity that is observed in patients coinfected with schistosomiasis and HCV is related, at least in part, to direct stimulation of viral replication by SEA[25].

It is interesting to consider that Derbala et al. found no significant difference in the treatment responses of patients treated with and without bilharziasis[26]. This finding might be explained by phenotypic variations in Egyptian patients infected with HCV genotype 4, whereby some patients may mount HCV-specific T cell responses, both CD4+ and CD8+, despite the prevalence of concomitant schistosomiasis[27].

A major limitation of this study was the need to diagnose schistosomiasis in patients by using an antischistosomal serology approach with a commercially available indirect hemagglutination test (IHAT). While the IHAT is sensitive in detecting bilharziasis, it cannot differentiate between past and current infection status nor between Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma haematobium species. While rectal snips are the preferred method of schistosomiasis diagnosis, this approach was not possible in our study population due to the large number of participants. Finally, genotyping for HCV was not performed on the patients in our study, since approximately 90% of infections in Egypt are due to genotype 4[9] and the Egyptian National Committee for Control of Viral Hepatitis does not recommend routine genotyping.

In conclusion, positive schistosomal serology has no effect on fibrosis stage but it is significantly associated with failure of response to HCV treatment despite antischistosomal therapy.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major public health problem and is the primary cause of liver fibrosis and chronic liver disease worldwide. Both HCV and schistosomiasis are highly endemic in Egypt and cases of coinfection are frequently encountered. Intriguingly, HCV prevalence shows a direct correlation to the amount of intravenous tartar emetic used to control schistosomiasis in some geographic regions of Egypt. Moreover, patients with hepatosplenic schistosomiasis show a higher susceptibility to coinfection with hepatitis B virus and HCV than healthy individuals.

HCV/Schistosomiasis coinfected patients are characterized by higher HCV RNA titers, histological activity, incidence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as higher mortality rates than monoinfected patients. This research aimed to assess the influence of schistosomiasis on hepatic fibrosis and to evaluate the response to pegylated-interferon/ribavirin (PEG-IFN/RIB) therapy in patients with chronic HCV infection.

Results showed that 27.3% of the patients had positive schistosomal serology, with a prevalence towards males (15.9% female and 84.1% male). The extent of fibrosis was not significantly different between patients with HCV/schistosomiasis coinfection and patients with chronic HCV monoinfection. Patients with HCV/schistosomiasis coinfection showed lower rates of early virologic response and virological response at week 24 of antiviral treatment, as well as lower rates of end-treatment response and sustained virological response. Schistosomiasis appears to be significantly associated with failure to respond to HCV treatment despite antischistosomal therapy.

Schistosomiasis appears to be significantly associated with failure to respond to HCV treatment. Authors propose that mandatory schistosomal serology should be considered for chronic HCV patients prior to initiating PEG-IFN/RIB therapy. In those patients with positive schistosomal serology, administration of antischistosomal therapy (praziquantel at 40 mg/kg single dose) four weeks prior to antiviral therapy (PEG-IFN/RIB) may decrease the effect of schistosomiasis, reduce subsequent complications and improve response to treatment.

Early virological response is defined as a ≥ 2 log reduction or complete absence of serum HCV RNA at week 12 of therapy, as compared to the baseline level. End-of-treatment response is defined as an undetectable level of virus (by polymerase chain reaction) in serum at the end of a 48-wk course of therapy (for patients infected with HCV genotype 4). Sustained virological response is defined as an undetectable level of HCV RNA in serum at 24 wk after the discontinuation of therapy. Virological breakthrough refers to the reappearance of HCV RNA during the ongoing course of therapy.

This study analyzes the impact of schistosomiasis on hepatic fibrosis and response to PEG-IFN/RIB therapy in patients with chronic HCV. The results suggest that positive schistosomal serology has no effect on fibrosis stage, but is significantly associated with failure to respond to HCV treatment.

P- Reviewers Lonardo A, Aghakhani A, Antonelli A S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335-1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2320] [Cited by in RCA: 2242] [Article Influence: 140.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | El-Zanaty F, Way A. Egypt Demographic and Health Survey 2008. 2009. Cairo: Ministry of Health, El-Zanaty and Associates, and Macro International 2009; . |

| 3. | Friedman SL. Molecular regulation of hepatic fibrosis, an integrated cellular response to tissue injury. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2247-2250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1567] [Cited by in RCA: 1597] [Article Influence: 63.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2006;368:1106-1118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1526] [Cited by in RCA: 1530] [Article Influence: 80.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Inter-country Meeting on Strategies to Eliminate Schistosomiasis from the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Proceedings from the World Health Organization Conference. . |

| 6. | El-Khoby T, Galal N, Fenwick A, Barakat R, El-Hawey A, Nooman Z, Habib M, Abdel-Wahab F, Gabr NS, Hammam HM. The epidemiology of schistosomiasis in Egypt: summary findings in nine governorates. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:88-99. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kamal SM, Rasenack JW, Bianchi L, Al Tawil A, El Sayed Khalifa K, Peter T, Mansour H, Ezzat W, Koziel M. Acute hepatitis C without and with schistosomiasis: correlation with hepatitis C-specific CD4(+) T-cell and cytokine response. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:646-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aquino RT, Chieffi PP, Catunda SM, Araújo MF, Ribeiro MC, Taddeo EF, Rolim EG. Hepatitis B and C virus markers among patients with hepatosplenic mansonic schistosomiasis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2000;42:313-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Strickland GT. Liver disease in Egypt: hepatitis C superseded schistosomiasis as a result of iatrogenic and biological factors. Hepatology. 2006;43:915-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Intraobserver and interobserver variations in liver biopsy interpretation in patients with chronic hepatitis C. The French METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology. 1994;20:15-20. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Frank C, Mohamed MK, Strickland GT, Lavanchy D, Arthur RR, Magder LS, El Khoby T, Abdel-Wahab Y, Aly Ohn ES, Anwar W. The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Lancet. 2000;355:887-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 694] [Cited by in RCA: 684] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kamal SM, Graham CS, He Q, Bianchi L, Tawil AA, Rasenack JW, Khalifa KA, Massoud MM, Koziel MJ. Kinetics of intrahepatic hepatitis C virus (HCV)-specific CD4+ T cell responses in HCV and Schistosoma mansoni coinfection: relation to progression of liver fibrosis. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1140-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kamal SM, Turner B, He Q, Rasenack J, Bianchi L, Al Tawil A, Nooman A, Massoud M, Koziel MJ, Afdhal NH. Progression of fibrosis in hepatitis C with and without schistosomiasis: correlation with serum markers of fibrosis. Hepatology. 2006;43:771-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ahmed L, Salama H, Ahmed R, Mahgoub AMA, Hamdy S, Abd Al Shafi S, Al Akel W, Hareedy A, Fathy W. Evaluation of Fibrosis Sero-Markers versus Liver Biopsy in Egyptian Patients with Hepatitis C and/or NASH and/or Schistosomiasis. PUJ. 2009;2:67-76. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Farah IO, Mola PW, Kariuki TM, Nyindo M, Blanton RE, King CL. Repeated exposure induces periportal fibrosis in Schistosoma mansoni-infected baboons: role of TGF-beta and IL-4. J Immunol. 2000;164:5337-5343. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Andrade ZA. Schistosomal hepatopathy. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99:51-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Blanton RE, Salam EA, Ehsan A, King CH, Goddard KA. Schistosomal hepatic fibrosis and the interferon gamma receptor: a linkage analysis using single-nucleotide polymorphic markers. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13:660-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liang YJ, Luo J, Yuan Q, Zheng D, Liu YP, Shi L, Zhou Y, Chen AL, Ren YY, Sun KY. New insight into the antifibrotic effects of praziquantel on mice in infection with Schistosoma japonicum. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Morcos SH, Khayyal MT, Mansour MM, Saleh S, Ishak EA, Girgis NI, Dunn MA. Reversal of hepatic fibrosis after praziquantel therapy of murine schistosomiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1985;34:314-321. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Berhe N, Myrvang B, Gundersen SG. Reversibility of schistosomal periportal thickening/fibrosis after praziquantel therapy: a twenty-six month follow-up study in Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:228-234. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Frenzel K, Grigull L, Odongo-Aginya E, Ndugwa CM, Loroni-Lakwo T, Schweigmann U, Vester U, Spannbrucker N, Doehring E. Evidence for a long-term effect of a single dose of praziquantel on Schistosoma mansoni-induced hepatosplenic lesions in northern Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:927-931. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Rossi E, Adams LA, Bulsara M, Jeffrey GP. Assessing liver fibrosis with serum marker models. Clin Biochem Rev. 2007;28:3-10. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Kamal S, Madwar M, Bianchi L, Tawil AE, Fawzy R, Peters T, Rasenack JW. Clinical, virological and histopathological features: long-term follow-up in patients with chronic hepatitis C co-infected with S. mansoni. Liver. 2000;20:281-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bahgat MM, El-Far MA, Mesalam AA, Ismaeil AA, Ibrahim AA, Gewaid HE, Maghraby AS, Ali MA, Abd-Elshafy DN. Schistosoma mansoni soluble egg antigens enhance HCV replication in mammalian cells. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:226-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | El-Awady MK, Youssef SS, Omran MH, Tabll AA, El Garf WT, Salem AM. Soluble egg antigen of Schistosoma Haematobium induces HCV replication in PBMC from patients with chronic HCV infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Derbala MF, Al Kaabi SR, El Dweik NZ, Pasic F, Butt MT, Yakoob R, Al-Marri A, Amer AM, Morad N, Bener A. Treatment of hepatitis C virus genotype 4 with peginterferon alfa-2a: impact of bilharziasis and fibrosis stage. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5692-5698. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Elrefaei M, El-sheikh N, Kamal K, Cao H. Analysis of T cell responses against hepatitis C virus genotype 4 in Egypt. J Hepatol. 2004;40:313-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |