Published online May 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i17.2650

Revised: February 27, 2013

Accepted: March 6, 2013

Published online: May 7, 2013

Processing time: 187 Days and 13.3 Hours

AIM: To develop a prognostic model to predict survival of patients with colorectal cancer (CRC).

METHODS: Survival data of 837 CRC patients undergoing surgery between 1996 and 2006 were collected and analyzed by univariate analysis and Cox proportional hazard regression model to reveal the prognostic factors for CRC. All data were recorded using a standard data form and analyzed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). Survival curves were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The log rank test was used to assess differences in survival. Univariate hazard ratios and significant and independent predictors of disease-specific survival and were identified by Cox proportional hazard analysis. The stepwise procedure was set to a threshold of 0.05. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS: The survival rate was 74% at 3 years and 68% at 5 years. The results of univariate analysis suggested age, preoperative obstruction, serum carcinoembryonic antigen level at diagnosis, status of resection, tumor size, histological grade, pathological type, lymphovascular invasion, invasion of adjacent organs, and tumor node metastasis (TNM) staging were positive prognostic factors (P < 0.05). Lymph node ratio (LNR) was also a strong prognostic factor in stage III CRC (P < 0.0001). We divided 341 stage III patients into three groups according to LNR values (LNR1, LNR ≤ 0.33, n = 211; LNR2, LNR 0.34-0.66, n = 76; and LNR3, LNR ≥ 0.67, n = 54). Univariate analysis showed a significant statistical difference in 3-year survival among these groups: LNR1, 73%; LNR2, 55%; and LNR3, 42% (P < 0.0001). The multivariate analysis results showed that histological grade, depth of bowel wall invasion, and number of metastatic lymph nodes were the most important prognostic factors for CRC if we did not consider the interaction of the TNM staging system (P < 0.05). When the TNM staging was taken into account, histological grade lost its statistical significance, while the specific TNM staging system showed a statistically significant difference (P < 0.0001).

CONCLUSION: The overall survival of CRC patients has improved between 1996 and 2006. LNR is a powerful factor for estimating the survival of stage III CRC patients.

Core tip: Recent reports and reviews have highlighted the importance of metastatic lymph node and Lymph node ratio (LNR) in predicting prognosis of colorectal cancer (CRC). We found that the histological grade, depth of bowel wall invasion, and number of metastatic lymph nodes were the most important prognostic factor for CRC without consideration of the interaction of the tumor node metastasis staging system. LNR was a powerful factor for estimating the survival of stage III CRC. This paper presents new results on the 5-year overall survival and prognostic factors in Chinese CRC patients.

- Citation: Yuan Y, Li MD, Hu HG, Dong CX, Chen JQ, Li XF, Li JJ, Shen H. Prognostic and survival analysis of 837 Chinese colorectal cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(17): 2650-2659

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i17/2650.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i17.2650

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies and one of the most common causes of cancer-related death worldwide[1]. An estimated 143460 new cases of CRC will be diagnosed this year, and 51690 patients will succumb to their disease in the United States alone[2]. Meanwhile, with the continuous aging of the population and an increased tendency to adopt a western lifestyle, the incidence of CRC and its related mortality is gradually increasing and it has become the fifth most common of all cancers in China[3,4]. Thus, the importance of CRC as a public health problem is increasing in China.

Over the past two decades, the 5-year overall survival of CRC patients has improved. Some advanced CRC patients have received clear survival benefits due to the practice of resecting liver metastases and advances in surgical techniques[5]. For those patients who have missed the opportunity for surgery, chemotherapy is still the main treatment. Although the overall survival of advanced CRC patients is still poorer than for early stage patients, it is encouraging that the combination of chemotherapy and targeted drugs may have the potential to improve survival.

In clinical practice, clinicians need an accurate outcome prediction of CRC patients to devise an appropriate therapeutic strategy. However, many variables may influence the prognosis, including both patient and tumor characteristics[6]. Therefore, we conducted the present study to explore the relevant factors affecting the prognosis of CRC patients using existing data in the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University College of Medicine, China.

A total of 837 patients with CRC that underwent surgery at the Department of Surgical Oncology at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University College of Medicine from January 1996 to December 2006 were enrolled from our database. All clinical cases and their follow-up data were recorded. The data included sex, age at diagnosis, clinical symptoms, severe complications, location of the primary tumor, histological type, tumor differentiation, lymphovascular invasion, depth of invasion, numbers of retrieved lymph nodes and metastatic lymph nodes, date of surgery, date of recurrence (if applicable), cause of recurrence (if applicable), date of death (if applicable), cause of death (if applicable), postoperative treatment, and date of follow-up. This study consisted of stages I-IV CRC patients. No local or systemic treatment had been conducted preoperatively. Patients’ blood samples were collected before their operation and their carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels were analyzed. Specimens were fixed in formalin and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and used for histopathological evaluation. The 6th and the 7th editions of the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) classification were used to categorize colorectal carcinomas. Rectal cancer was defined as carcinomas with a distal margin of 15 cm from the anal verge measured with a rigid endoscope.

All patients were followed up at 3-mo intervals for the first 2 years, and 6-mo intervals for 3-5 years. Follow-up was completed for the entire study population by March 2011, and the median follow-up period was 45 mo. The baseline of the study cases are shown in Table 1 (six cases of double primary CRC were excluded from Table 1).

| Basic data | Colon cancer (n = 437) | Rectal cancer (n = 394) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 245 (56.1) | 245 (62.2) |

| Female | 192 (43.9) | 149 (37.8) |

| Age at operation1 (yr) | 60.9 ± 13.1 | 58.3 ± 12.7 |

| Dukes’ staging | ||

| A | 38 (8.7) | 81 (20.6) |

| B | 181 (41.4) | 117 (29.7) |

| C | 166 (38.0) | 172 (43.7) |

| D | 49 (11.2) | 23 (5.8) |

| Status of resection | ||

| Curative | 356 (81.5) | 349 (88.6) |

| Palliative | 62 (14.2) | 33 (8.4) |

| Undefined | 19 (4.3) | 12 (3.0) |

| Tumor size | ||

| ≥ 5 cm | 154 (35.2) | 64 (16.2) |

| < 5 cm | 247 (56.5) | 263 (66.8) |

| Undefined | 36 (8.2) | 67 (17.1) |

| Histological differentiation grade | ||

| Well | 93 (21.3) | 118 (29.9) |

| Moderate | 184 (42.1) | 180 (45.7) |

| Poor | 108 (24.7) | 61 (15.5) |

| Undefined | 52 (11.9) | 35 (8.9) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||

| Positive | 14 (3.2) | 10 (2.5) |

| Negative | 423 (96.8) | 384 (97.5) |

| Perineural invasion | ||

| Positive | 11 (2.5) | 3 (0.8) |

| Negative | 423 (96.8) | 391 (99.2) |

| Invasion of adjacent organs | ||

| Positive | 37 (8.5) | 15 (3.8) |

| Negative | 396 (90.6) | 379 (96.2) |

| Undefined | 4 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

All data were recorded using a standard data form and analyzed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). Survival curves were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The log rank test was used to assess differences in survival. Univariate hazard ratios and significant and independent predictors of disease-specific survival and were identified by Cox proportional hazard analysis. The stepwise procedure was set to a threshold of 0.05. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

A total of 837 patients with CRC were enrolled. The 3-year and 5-year survival for all 837 patients was 74% and 68%, respectively. Table 2 summarizes the univariate analysis results of different clinical and pathological features.

| n | 3-YSR | 5-YSR | P value1 | |

| Age group (yr) | 0.002 | |||

| Age1 ( ≤ 35) | 29 | 65% | 65% | |

| Age2 (36–59) | 370 | 73% | 66% | |

| Age3 (60–74) | 334 | 78% | 74% | |

| Age4 (≥ 75) | 104 | 61% | 53% | |

| Sex | 0.834 | |||

| Male | 495 | 73% | 67% | |

| Female | 342 | 74% | 69% | |

| Family history of CRC | 0.391 | |||

| Negative | 812 | 73% | 68% | |

| Positive | 25 | 91% | 82% | |

| Obstruction | 0.000 | |||

| Negative | 790 | 76% | 70% | |

| Positive | 45 | 39% | 35% | |

| Perforation | 0.629 | |||

| Negative | 824 | 74% | 68% | |

| Positive | 11 | 68% | 68% | |

| Bleeding | 0.116 | |||

| Negative | 289 | 69% | 66% | |

| Positive | 546 | 76% | 69% | |

| Diarrhea | 0.421 | |||

| Negative | 750 | 75% | 68% | |

| Positive | 85 | 65% | 63% | |

| Constipation | 0.415 | |||

| Negative | 776 | 74% | 68% | |

| Positive | 59 | 72% | 66% | |

| Habits changes | 0.547 | |||

| Negative | 531 | 74% | 69% | |

| Positive | 304 | 73% | 66% | |

| Serum CEA level | 0.042 | |||

| ≤ 5 ng/mL | 661 | 74% | 69% | |

| > 5 ng/mL | 172 | 71% | 62% | |

| Status of resection | 0.000 | |||

| Curative | 711 | 80% | 74% | |

| Palliative | 95 | 29% | 22% | |

| Tumor location | 0.705 | |||

| Colon cancer | 437 | 73% | 69% | |

| Rectal cancer | 394 | 74% | 66% | |

| Double primary of colon and rectal cancer | 6 | 75% | 75% | |

| Tumor size | 0.004 | |||

| < 5 cm | 516 | 77% | 71% | |

| ≥ 5 cm | 218 | 67% | 62% | |

| Histological differentiation grade | 0.001 | |||

| Well | 212 | 78% | 71% | |

| Moderate | 366 | 73% | 65% | |

| Poor | 170 | 62% | 60% | |

| Pathological types | 0.036 | |||

| Non-mucous cell carcinoma | 663 | 76% | 70% | |

| Mucous cell carcinoma | 141 | 63% | 59% | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0.000 | |||

| Negative | 813 | 75% | 69% | |

| Positive | 24 | 44% | 36% | |

| Perineural invasion | 0.057 | |||

| Negative | 820 | 74% | 68% | |

| Positive | 14 | 42% | 42% | |

| Invasion of adjacent organs | 0.000 | |||

| Negative | 781 | 75% | 70% | |

| Positive | 52 | 43% | 33% |

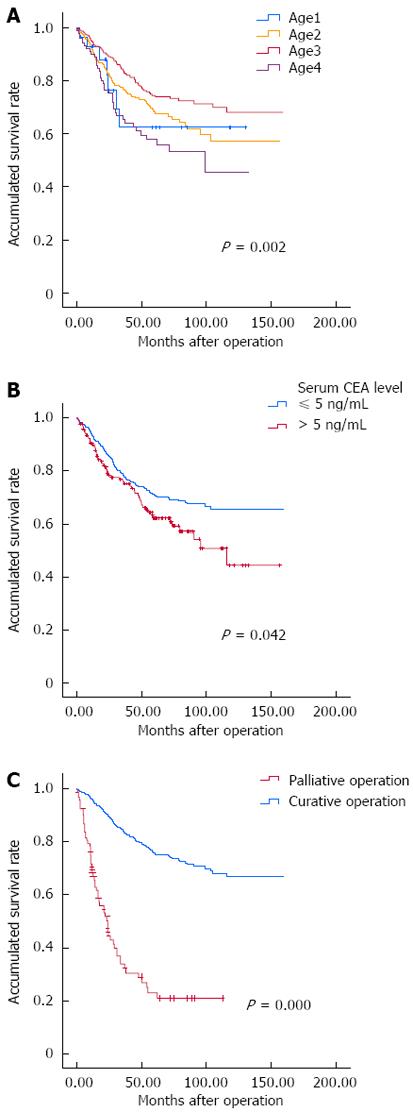

Most patients (n = 808) were diagnosed in middle age (median age: 60 years, range: 19-91 years) and 29 were diagnosed at ≤ 35 years of age. Patients were divided into four groups according to age at diagnosis: age1 ≤ 35 years, age2 36-59 years, age3 60-74 years, and age4 ≥ 75 years (Figure 1A). A significant difference in 5-year survival was found between these four groups: age1 65%, age2 66%, age3 74%, and age4 53% (P = 0.002).

Among the 837 patients, 495 were male and 342 were female. There was no sex difference in survival (P = 0.834). Clinical features of 437 colon cancer patients and 394 rectal cancer patients were recorded. We also found six cases of double primary colon cancer and rectal cancer. In spite of a higher incidence of colon cancer, there were no significant differences in survival between patients with colon cancer and rectal cancer.

There were 25 patients who had a family history of CRC. It seemed that they had a trend toward better survival than the other 812 patients without a CRC-related family history. The difference was not statistically significant; 3-year survival was 91% vs 73% and 5-year survival was 82% vs 68% (P = 0.391).

According to the results of univariate analysis, patients with obvious clinical symptoms, such as tumor-related obstruction, perforation, diarrhea, constipation, and change of bowel habits had a shorter survival (Table 2). However, only the difference in tumor-related obstruction was statistically significant. The 3-year and 5-year survival of 45 patients with preoperative bowel obstruction was 39% and 35% respectively vs 76% and 70% in patients without symptoms (P < 0.0001). In addition to the clinical symptoms, serum carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA) level is commonly used as a screening and predictive factor for CRC patients (Figure 1B). In our study, the prognosis for patients with high CEA levels of > 5 ng/mL at diagnosis was worse than those who with low CEA levels; 3-year survival was 71% vs 74% and 5-year survival 62% vs 69% (P = 0.042).

Surgery plays an important role in the treatment of CRC, and radical resection of tumors also has a major influence on prognosis. In our study, 711/837 CRC patients underwent curative surgery, while 95 had palliative surgery due to serious complications or for other reasons (Figure 1C). Compared with patients who had curative surgery, there was a significant decrease in postoperative survival in patients who had palliative surgery; 3-year survival of 80% vs 29% and 5-year survival of 74% vs 22% (P < 0.0001). This confirms that curative surgery is one of the crucial factors affecting prognosis of CRC patients. In addition, the maximum length of the primary lesion, tumor differentiation, histological type, depth of bowel wall invasion, lymphovascular invasion, and invasion of adjacent organs may affect the prognosis of CRC patients (P < 0.05, Table 2).

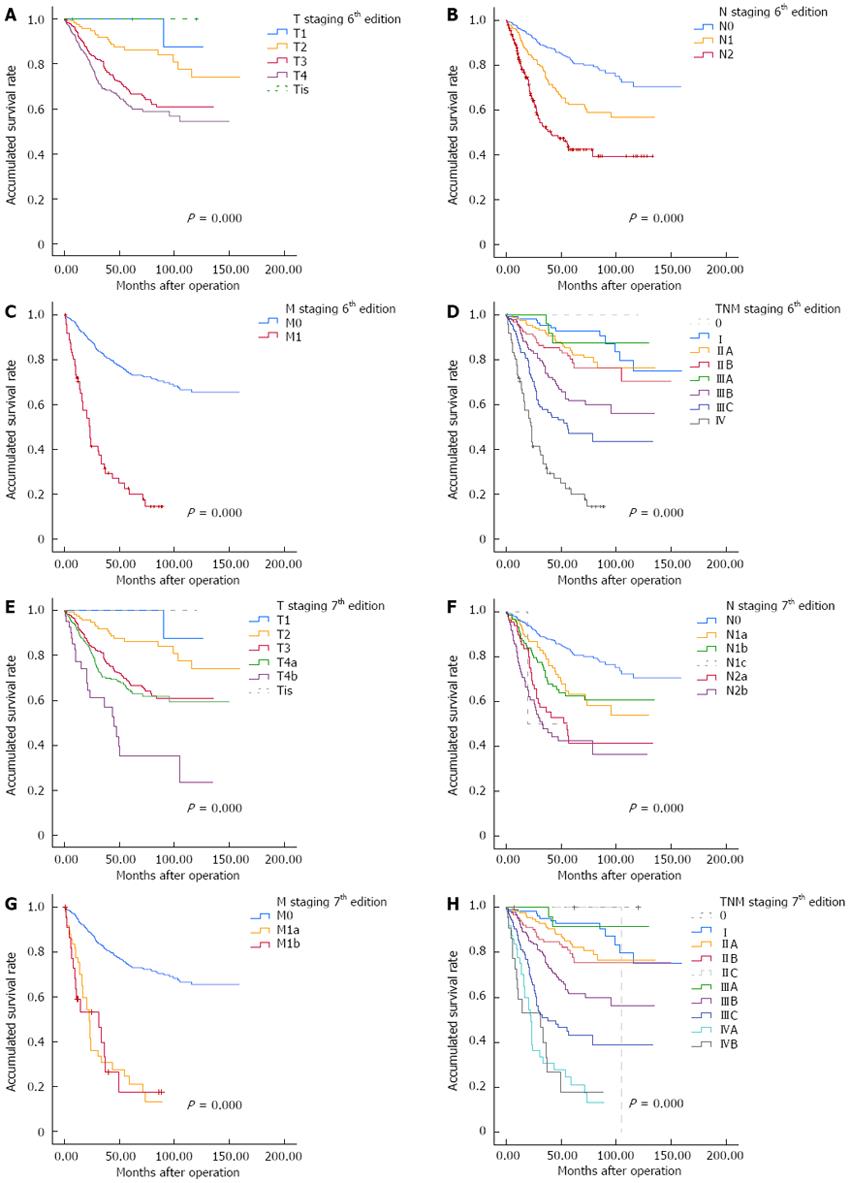

Currently, the TNM staging system is widely accepted for tumor staging globally, and also represents the main staging system in our country. The 6th revision is regarded as being a significant improvement in CRC staging and the 7th revision is considered to be a major turning point in the evolution of cancer staging[7]. Regardless of the edition used for staging, survival of CRC patients gradually declined with increase in depth of infiltration of the primary tumor, the number of positive lymph nodes estimated, and status of distant metastases (Table 3, Figure 2). We also found that survival of stage IIIA patients was better than of stage IIB patients regardless of which edition was used to classify postoperative staging: with the 6th edition, 5-year survival of stage IIB and IIIA was 75% and 87% (P < 0.0001), and for the 7th edition, 5-year survival of stages IIB and IIIA was 75% and 91% (P < 0.0001).

| 6th edition of TNM staging system | 7th edition of TNM staging system | ||||||||

| n | 3-YSR | 5-YSR | P value | n | 3-YSR | 5-YSR | P value | ||

| pT | 0.000 | pT | 0.000 | ||||||

| T1 | 35 | 100% | 100% | T1 | 35 | 100% | 100% | ||

| T2 | 128 | 87% | 86% | T2 | 128 | 87% | 86% | ||

| T3 | 324 | 73% | 66% | T3 | 324 | 73% | 66% | ||

| T4 | 345 | 66% | 59% | T4a | 303 | 69% | 62% | ||

| T4b | 42 | 45% | 33% | ||||||

| Undefined | 5 | 78% | 78% | Undefined | 5 | 78% | 78% | ||

| pN | 0.000 | pN | 0.000 | ||||||

| N0 | 445 | 86% | 80% | N0 | 444 | 86% | 80% | ||

| N1 | 224 | 68% | 61% | N1a | 103 | 71% | 63% | ||

| N2 | 168 | 48% | 43% | N1b | 120 | 66% | 61% | ||

| N1c | 2 | 50% | / | ||||||

| N2a | 82 | 54% | 43% | ||||||

| N2b | 86 | 42% | 42% | ||||||

| pM | 0.000 | pM | 0.000 | ||||||

| M0 | 765 | 78% | 73% | M0 | 765 | 78% | 73% | ||

| M1 | 72 | 28% | 18% | M1a | 49 | 29% | 19% | ||

| M1b | 23 | 26% | 17% | ||||||

| Stage | 0.000 | Stage | 0.000 | ||||||

| I | 121 | 93% | 93% | I | 121 | 93% | 93% | ||

| IIA | 173 | 88% | 81% | IIA | 173 | 88% | 81% | ||

| IIB | 125 | 85% | 75% | IIB | 121 | 85% | 75% | ||

| IIIA | 33 | 87% | 87% | IIC | 5 | 100% | 100% | ||

| IIIB | 168 | 68% | 61% | IIIA | 33 | 91% | 91% | ||

| IIIC | 141 | 53% | 48% | IIIB | 199 | 69% | 61% | ||

| IV | 72 | 28% | 18% | IIIC | 109 | 47% | 44% | ||

| IVA | 49 | 29% | 19% | ||||||

| IVB | 23 | 26% | 17% | ||||||

| Undefined | 4 | 100% | 100% | Undefined | 4 | 100% | 100% | ||

LNR is defined as the ratio of positive lymph nodes divided by the total number of retrieved lymph nodes, and does not depend on the number of lymph nodes harvested[8]. It is considered to be an independent factor that reflects survival of CRC patients, especially those with stage III disease. We calculated the LNR values of 341 stage III cases. The mean LNR was 0.34 (median: 0.25, range: 0-1). Patients were divided into the following three LNR subgroups: LNR1, LNR ≤ 0.33, n = 211; LNR2, LNR 0.34-0.66, n = 76; and LNR3, LNR ≥ 0.67, n = 54 (Figure 3). Survival among these three groups was significantly different (P < 0.0001).

After we calculated the positive factors by univariate analysis, we used multivariate analysis (Cox proportional hazard model) to find the most significant prognostic factors (Table 4). First, we analyzed the interaction of the positive clinicopathological factors from univariate analysis, and multivariate analysis showed that histological grade, depth of bowel wall invasion, and number of metastatic lymph nodes affected the prognosis of CRC patients (P < 0.05). We performed another two separate multivariate analyses with the 6th and 7th TNM staging systems. We found that histological grade was no longer a positive item when considering the interaction of the TNM staging system (Table 4). Results for the 6th and 7th TNM staging systems in multivariate analysis showed significant differences (Table 4, P < 0.0001). Another two factors, the depth of bowel wall invasion and the number of metastatic lymph nodes, showed a positive statistical significance, regardless of which TNM staging system was used (Table 4, P < 0.05). Besides, with the increase in the number of metastatic lymph nodes with each level, the relative risk of death of CRC patients will increase 1.093 times without consideration of an exact clinical staging. However, this risk decreased to 1.037 times using the 6th TNM staging system and 1.047 times using the 7th system.

| P value | RR | 95%CI | |

| Without interplay tumor node metastasis staging system | |||

| Age group | 0.060 | 1.193 | 0.993-1.434 |

| Obstruction | 0.241 | 1.011 | 0.993-1.030 |

| Tumor size | 0.257 | 1.002 | 0.998-1.006 |

| Serum CEA level | 0.690 | 0.996 | 0.978-1.015 |

| Status of resection | 0.082 | 1.005 | 0.999-1.012 |

| Histological grade | 0.007 | 0.991 | 0.984-0.998 |

| Pathological types | 0.817 | 0.999 | 0.992-1.006 |

| Depth of bowel wall invasion | 0.000 | 1.047 | 1.028-1.067 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0.695 | 0.974 | 0.854-1.111 |

| Invasion of adjacent organs | 0.942 | 0.998 | 0.949-1.050 |

| Number of metastatic lymph nodes | 0.000 | 1.093 | 1.073-1.114 |

| With interplay 6th tumor node metastasis staging system | |||

| Age group | 0.054 | 1.194 | 0.997-1.430 |

| Obstruction | 0.386 | 1.008 | 0.990-1.028 |

| Tumor size | 0.259 | 1.002 | 0.998-1.006 |

| Serum CEA level | 0.789 | 0.997 | 0.979-1.017 |

| Status of resection | 0.136 | 1.005 | 0.999-1.011 |

| Histological grade | 0.114 | 0.995 | 0.988-1.001 |

| Pathological types | 0.290 | 0.996 | 0.989-1.003 |

| Depth of bowel wall invasion | 0.014 | 1.028 | 1.006-1.050 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0.758 | 0.981 | 0.869-1.108 |

| Invasion of adjacent organs | 0.840 | 0.994 | 0.935-1.056 |

| Number of metastatic lymph nodes | 0.006 | 1.037 | 1.010-1.065 |

| 6th TNM staging | 0.000 | 1.471 | 1.344-1.610 |

| With interplay of 7th tumor node metastasis staging system | |||

| Age group | 0.094 | 1.168 | 0.974-1.400 |

| Obstruction | 0.434 | 1.008 | 0.989-1.027 |

| Tumor size | 0.289 | 1.002 | 0.998-1.006 |

| Serum CEA level | 0.768 | 0.997 | 0.978-1.016 |

| Status of resection | 0.184 | 1.004 | 0.998-1.010 |

| Histological grade | 0.109 | 0.995 | 0.988-1.001 |

| Pathological types | 0.283 | 0.996 | 0.989-1.003 |

| Depth of bowel wall invasion | 0.023 | 1.025 | 1.003-1.048 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0.779 | 0.983 | 0.873-1.107 |

| Invasion of adjacent organs | 0.802 | 0.992 | 0.930-1.058 |

| Number of metastatic lymph nodes | 0.002 | 1.041 | 1.015-1.069 |

| 7th TNM staging | 0.000 | 1.354 | 1.261-1.454 |

CRC is the fifth most common cancer in China[3]. The morbidity and mortality of CRC have shown a clear upward trend in both urban and rural areas over the past 30 years. Although there has been an improvement in surgical techniques and treatment, the 5-year overall survival of CRC is still hovering around 60%. Park et al[9] have reported a 5-year survival rate of 67.2% in 2230 cases of CRC. In China, Lv et al[10] has reported 5-year survival rates of 58.4% and 64.5% 383 cases in colon and rectal cancer patients, respectively. In our study, the 3-year and 5-year survival of CRC patients was 74% and 68%, respectively. The postoperative 5-year survival increased to 74% in our hospital, compared with 66% during 1980-1999[11,12].

From 1980 to the 1990s, rectal cancer accounted for the main part of the incidence of CRC in China[4,11]. However, data from Table 2 showed a higher proportion of colon cancer than rectal cancer in our hospital from 1996 to 2006; with 437 cases vs 394 cases. Other researchers have reported similar results, which suggests that the proportion of rectal cancer cases is gradually declining[13-15]. Although the reason for the change is unclear, some experts have suggested that the higher incidence of colon cancer might be a complex result of changes in dietary habits, the higher rate of diagnosis of colon cancer, etiological changes, and the increased incidence of right colon cancer[16-20].

In addition to the change in location of disease, the age at onset has also changed. Previously, CRC had a higher incidence in elderly people[21]. However, recent results at home and abroad have found that detection of CRC in the younger population is increasing[22]. CRC in young patients is generally considered a more aggressive disease, which presents at a later stage and has poorer pathological features[23,24]. Zhong et al[25] have reported only a 27.51% 5-year survival rate in young Chinese patients with CRC. In our study, the 5-year survival in the low-age group (age1) was 65%, which was slightly lower than the overall rate (68%), although it had improved from the 5-year survival rate of 53% in patients aged ≤ 40 years at our hospital between 1980 and 1999[26]. It should be noted that there is no international standard definition of young or old, and the definition of low age in our study is different from that used by Cai et al[26]. The overall survival between different age groups showed a significant difference in univariate analysis (Figure 1A), but failed to show a significant difference in the multivariate analysis.

Some reports have suggested that several clinicopathological features contribute to the unfavorable prognosis of CRC in young patients[27-29]. A review of the literature has suggested that younger patients with CRC, without relevant predisposing risk factors, have more advanced stages of disease, more aggressive histopathological characteristics, and a poorer prognosis compared with older patients[24]. However, there is also some evidence to show that cancer-related survival in young CRC patients seems no less favorable compared with older patients[30-32].

The current international standard for CRC staging is the TNM system. The 7th edition of TNM staging, developed by the UICC and American Joint Committee on Cancer, has undergone some significant changes from the 6th edition. We tested which of the two versions could predict survival more accurately. Results of univariate analysis showed values in both staging systems were statistically significant prognostic factors (P < 0.05). Figure 2D and H demonstrate the differences from stage I to stage IV disease. Similarly, both the 6th and 7th TNM staging systems were effective for judging the clinical survival and prognosis of CRC based on the results of multivariate analysis. The results also suggest a higher relative risk of death in CRC patients with more metastatic lymph nodes with an unclear clinical staging. It is worth noting that the patients with stage IIIA disease had a better survival than patients with stage IIB disease, as determined from the follow-up data. It might be explained by stage IIIA patients routinely receiving chemotherapy after their operation as part of current clinical practice, while stage IIB patients do not. Some authors also hold the view that lower survival of stage II CRC patients might be related to the particular biological behavior of stage II tumors[33-35].

Lymph node metastasis is a significant component of TNM staging of CRC. Tumor stage and the number of lymph nodes retrieved at resection influence the accuracy of determining nodal status in CRC. They also influence the postoperative treatment strategy of CRC patients. In our study, we took the T, N and M stage as factors in univariate analysis and obtained positive results (Table 3, Figure 2). In addition, multivariate analysis demonstrated a strong relationship between the number of metastatic lymph nodes and survival of CRC patients (Table 4). The relative risk of death is increased with the number of metastatic lymph nodes. The number of lymph nodes found after surgical resection was positively associated with survival of patients with stage II and III colon cancer[36,37]. An underestimation of the nodal stage may lead to a high risk of local recurrence and influence decisions regarding adjuvant therapy, as well as influencing the overall prognosis[38-41]. According to the result of the INT-0089 trial, National Comprehensive Cancer Network Colon Cancer Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend that retrieval and examination of ≥ 12 lymph nodes can be regarded as adequate lymphadenectomy for accurate staging[42].

There is a difference between the number of metastatic lymph nodes reported during surgery and the actual number of metastatic lymph nodes. The difference may result from many factors, including the extent of surgical dissection and the thoroughness of the pathologists. Cases with insufficient retrieval and undetected lymph nodes are not unusual in clinical practice, although the concept of taking a sufficient number of lymph nodes during surgery to ensure exact postoperative staging is currently agreed. Evaluating lymph node metastasis has become a prognostic factor for CRC, and LNR is an important component of staging. LNR has also been identified as being of significant prognostic value in breast and gastric cancer[43,44]. Berger et al[45] were the first to suggest LNR as an important prognostic factor after curative resection for CRC. It was then established as a powerful independent index of CRC that reflected the probability of positive lymph nodes based on the number of retrieved lymph nodes[8,46-48]. In our study, we found a dramatic decrease in survival with an increase in LNR in stage III CRC patients (P < 0.0001, Figure 3).

Although the LNR has been emphasized as an important prognostic factor, quantification should be followed for clinical validity. Song et al[49] have compared three prognostic factors of CRC and have concluded that LNR classification is a more reliable N classification than the nodal staging in the TNM system and LODDS:

defined as

, pnod is the number of positive lymph nodes, tnod is the total number of lymph nodes retrieved, and 0.5 is added to both numerator and denomination to avoid singularity[49]. They believe that LNR is superior to the other two indexes for the following reasons: (1) LNR could contribute to accuracy in prognostic assessment; (2) when the retrieved lymph node numbers is insufficient, TNM nodal staging will be inappropriate for staging migration and will even underestimate prognosis; and (3) as a novel indicator for predicting the status of lymph nodes, evidence of LODDS in CRC is inadequate and is more difficult to calculate and inconvenient for clinical practice[50]. When the number of examined lymph nodes is inadequate, LNR is a simple and powerful index to assess the prognosis of CRC patients.

In conclusion, based on the results from our study, we were delighted to find the overall survival in our hospital had improved between 1996 and 2006. Younger patients with CRC have attracted attention because of the increasing number of new cases, their adverse clinicopathological features, and poor prognosis. However, there is still a debate about the prognosis and clinicopathological features of CRC in young compared to old patients. The pathogenesis and mechanism of disease are still unclear. The overall survival in patients with stage IIIA CRC was better than that in patients with stage IIB disease. This might be a combination of the special biological behavior of stage II CRC and the type of medical intervention for stage III CRC patients. The exact mechanisms of these problems and phenomena need further study.

By using multivariate analysis, we found that tumor histological grade, depth of bowel wall invasion, and metastatic lymph node numbers were independent prognostic factors for patients with CRC if we did not consider the exact clinical staging. We also found other important factors that could affect the prognosis of patients with CRC by univariate analysis, such as patient age, status of resection, and invasion of adjacent organs. The relative risk of death in CRC patients increases with the number of metastatic lymph nodes with an unclear clinical staging, which emphasizes the importance of correct clinical staging.

Surgeons know that a curative operation can greatly improve the overall survival of CRC patients, and resection of a sufficient number of lymph nodes is a necessity for proper postoperative staging. LNR is a powerful factor for assessment of prognosis in stage III CRC patients and is worthy of use in daily practice for evaluating a patient’s risk of death. However, we should combine it with other complex factors that together can make a complete assessment so we can devise a proper plan for further treatment.

Besides appropriate treatment, a sensible follow-up plan should be given to CRC patients with full consideration of the factors mentioned above. Moreover, we should devise treatment strategies carefully based on the concept of individualized treatment according to each patient’s clinical features, to improve survival and prognosis, especially for those patients with risk factors. In addition, early screening and surveillance by appropriate methods may improve the overall survival of CRC.

In recent years, the morbidity and mortality of colorectal cancer (CRC) has risen in the Chinese population. Although the 5-year overall survival of CRC patients has improved, the overall survival of advanced CRC patients is still poor. There are many impact factors that could influence the prognosis of CRC patients. Thus, a proper model for predicting the prognosis of CRC patients is necessary for both surgeons and physicians.

Nowadays, the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system is approved and widely used for clinical staging of CRC patients. As the latest version of TNM staging system, the 7th edition of TNM staging system is considered to represent a major turning point in the evaluation of CRC staging. However, less information of the real assessment validity between the 6th and 7th versions is available in Chinese populations.

Recent reports and reviews have highlighted the importance of metastatic lymph node and lymph node ratio (LNR) in predicting prognosis of CRC patients. LNR is an easy but powerful index to evaluate prognosis in stage III CRC patients.

Using univariate analysis and Cox proportional hazard regression model, we found that histological grade, depth of bowel wall invasion, and number of metastatic lymph nodes were the most important prognostic factors for CRC without consideration of the interaction of the TNM staging system. LNR is a powerful factor for estimating the survival of stage III CRC patients.

LNR is defined as the ratio of positive lymph nodes divided by the total number of retrieved lymph nodes, and does not depend on the number of lymph nodes harvested. It is considered an independent factor that reflects survival of CRC patients, especially those with stage III disease.

This article is helpful and creative for clinical significance. The results of this article verified the predictive affection of tumor invasion, lymph node metastasis and lymph node ratio. Meanwhile, it concludes that the 6th and 7th National Comprehensive Cancer Network TNM staging systems are both effective to predict the survival of colorectal cancer patients.

P- Reviewers de Bree E, Zoller M, Ji JF S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Zhang YL, Zhang ZS, Wu BP, Zhou DY. Early diagnosis for colorectal cancer in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:21-25. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8406] [Cited by in RCA: 8970] [Article Influence: 690.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yang L, Li LD, Chen YD. Cancer Incidence and Mortality Estimates and Prediction for year 2000 and 2005 in China. Zhongguo Weisheng Tongji. 2005;22:218-223. |

| 4. | Li M, GU J. Changing patterns of colorectal cancer over the recent two decades in China. Zhongguo Weichang Waike Zazhi. 2004;7:214-217. |

| 5. | Ostenfeld EB, Erichsen R, Iversen LH, Gandrup P, Nørgaard M, Jacobsen J. Survival of patients with colon and rectal cancer in central and northern Denmark, 1998-2009. Clin Epidemiol. 2011;3 Suppl 1:27-34. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Nan KJ, Qin HX, Yang G. Prognostic factors in 165 elderly colorectal cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2207-2210. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5537] [Cited by in RCA: 6453] [Article Influence: 430.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huh JW, Kim YJ, Kim HR. Ratio of metastatic to resected lymph nodes as a prognostic factor in node-positive colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2640-2646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Park YJ, Park KJ, Park JG, Lee KU, Choe KJ, Kim JP. Prognostic factors in 2230 Korean colorectal cancer patients: analysis of consecutively operated cases. World J Surg. 1999;23:721-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lv Y, Zhao P. Clinicopathologic and prognostic study on 383 cases of colorectal cancer. Zhonghua Zhongliu Fangzhi Zazhi. 2007;14:613-616. |

| 11. | Cai SR, Zheng S, Zhang SZ. Multivariable analysis of factors influencing survival of 842 colorectal cancer cases. Shiyong Zhongliu Zazhi. 2005;20:40-43. |

| 12. | Qu JM, Deng YC, Zhang XH. Multivariate COX-model analysis on the prognosis of colorectal cancer. Shiyong Zhongliu Zazhi. 2005;20:148-151. |

| 13. | Xu AG, Jiang B, Zhong XH, Yu ZJ, Liu JH. [The trend of clinical characteristics of colorectal cancer during the past 20 years in Guangdong province]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Zazhi. 2006;86:272-275. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Ji BT, Devesa SS, Chow WH, Jin F, Gao YT. Colorectal cancer incidence trends by subsite in urban Shanghai, 1972-1994. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:661-666. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Wan DS, Chen G, Pan ZZ, Ma GS, Liu H, Lu ZH, Zhou ZW. Dynamic Analysis of Hospitalized Colorectal Cancer patients in 35 years. Guangdong Yixue. 2001;7:2. |

| 16. | McMichael AJ, Potter JD. Diet and colon cancer: integration of the descriptive, analytic, and metabolic epidemiology. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1985;69:223-228. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Breivik J, Lothe RA, Meling GI, Rognum TO, Børresen-Dale AL, Gaudernack G. Different genetic pathways to proximal and distal colorectal cancer influenced by sex-related factors. Int J Cancer. 1997;74:664-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Distler P, Holt PR. Are right- and left-sided colon neoplasms distinct tumors? Dig Dis. 1997;15:302-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wu X, Chen VW, Martin J, Roffers S, Groves FD, Correa CN, Hamilton-Byrd E, Jemal A. Subsite-specific colorectal cancer incidence rates and stage distributions among Asians and Pacific Islanders in the United States, 1995 to 1999. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1215-1222. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Toyoda Y, Nakayama T, Ito Y, Ioka A, Tsukuma H. Trends in colorectal cancer incidence by subsite in Osaka, Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39:189-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, Wooldrage K, Hart AR, Northover JM, Parkin DM, Wardle J, Duffy SW, Cuzick J. Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1624-1633. [PubMed] |

| 22. | You YN, Xing Y, Feig BW, Chang GJ, Cormier JN. Young-onset colorectal cancer: is it time to pay attention? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:287-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Livingston EH, Yo CK. Colorectal cancer in the young. Am J Surg. 2004;187:343-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chou CL, Chang SC, Lin TC, Chen WS, Jiang JK, Wang HS, Yang SH, Liang WY, Lin JK. Differences in clinicopathological characteristics of colorectal cancer between younger and elderly patients: an analysis of 322 patients from a single institution. Am J Surg. 2011;202:574-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhong XH, Xu AG, Yu ZJ. Clinical feathers of youth colorectal cancer patients in China. Shiyong Zhongliu Zazhi. 2006;22:2028-2030. |

| 26. | Cai SR, Zheng S, Zhang SZ. [Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in colorectal cancer patients with different ages]. Zhonghua Zhongliu Zazhi. 2005;27:483-485. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Adloff M, Arnaud JP, Schloegel M, Thibaud D, Bergamaschi R. Colorectal cancer in patients under 40 years of age. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:322-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Liang JT, Huang KC, Cheng AL, Jeng YM, Wu MS, Wang SM. Clinicopathological and molecular biological features of colorectal cancer in patients less than 40 years of age. Br J Surg. 2003;90:205-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Alici S, Aykan NF, Sakar B, Bulutlar G, Kaytan E, Topuz E. Colorectal cancer in young patients: characteristics and outcome. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2003;199:85-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Liu JH, Etzioni DA, Ko CY. Are survival rates different for young and older patients with rectal cancer? Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:2064-2069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Li M, Li JY, Zhao AL, Gu J. Do young patients with colorectal cancer have a poorer prognosis than old patients? J Surg Res. 2011;167:231-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Schellerer VS, Merkel S, Schumann SC, Schlabrakowski A, Förtsch T, Schildberg C, Hohenberger W, Croner RS. Despite aggressive histopathology survival is not impaired in young patients with colorectal cancer: CRC in patients under 50 years of age. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:71-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Oh TY, Moon SM, Shin US, Lee HR, Park SH. Impact on Prognosis of Lymph Node Micrometastasis and Isolated Tumor Cells in Stage II Colorectal Cancer. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2011;27:71-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hebbar M, Adenis A, Révillion F, Duhamel A, Romano O, Truant S, Libersa C, Giraud C, Triboulet JP, Pruvot FR. E-selectin gene S128R polymorphism is associated with poor prognosis in patients with stage II or III colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1871-1876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Belly RT, Rosenblatt JD, Steinmann M, Toner J, Sun J, Shehadi J, Peacock JL, Raubertas RF, Jani N, Ryan CK. Detection of mutated K12-ras in histologically negative lymph nodes as an indicator of poor prognosis in stage II colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2001;1:110-116. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Chang GJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Skibber JM, Moyer VA. Lymph node evaluation and survival after curative resection of colon cancer: systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:433-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 708] [Cited by in RCA: 779] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Nagahashi M, Ramachandran S, Rashid OM, Takabe K. Lymphangiogenesis: a new player in cancer progression. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4003-4012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Yan G, Zhou XY, Cai SJ, Zhang GH, Peng JJ, Du X. Lymphangiogenic and angiogenic microvessel density in human primary sporadic colorectal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:101-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Joseph NE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, Wang H, Mayer RJ, MacDonald JS, Catalano PJ, Haller DG. Accuracy of determining nodal negativity in colorectal cancer on the basis of the number of nodes retrieved on resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Wong JH, Severino R, Honnebier MB, Tom P, Namiki TS. Number of nodes examined and staging accuracy in colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2896-2900. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Bilchik A. More (nodes) + more (analysis) = less (mortality): challenging the therapeutic equation for early-stage colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:203-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Le Voyer TE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, Mayer RJ, Macdonald JS, Catalano PJ, Haller DG. Colon cancer survival is associated with increasing number of lymph nodes analyzed: a secondary survey of intergroup trial INT-0089. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2912-2919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 821] [Cited by in RCA: 847] [Article Influence: 38.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Sierra A, Regueira FM, Hernández-Lizoáin JL, Pardo F, Martínez-Gonzalez MA, A-Cienfuegos J. Role of the extended lymphadenectomy in gastric cancer surgery: experience in a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:219-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Bando E, Yonemura Y, Taniguchi K, Fushida S, Fujimura T, Miwa K. Outcome of ratio of lymph node metastasis in gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:775-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Berger AC, Sigurdson ER, LeVoyer T, Hanlon A, Mayer RJ, Macdonald JS, Catalano PJ, Haller DG. Colon cancer survival is associated with decreasing ratio of metastatic to examined lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8706-8712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 408] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Huh JW, Kim CH, Kim HR, Kim YJ. Factors predicting oncologic outcomes in patients with fewer than 12 lymph nodes retrieved after curative resection for colon cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:125-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Hong KD, Lee SI, Moon HY. Lymph node ratio as determined by the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system predicts survival in stage III colon cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2011;103:406-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kobayashi H, Mochizuki H, Kato T, Mori T, Kameoka S, Shirouzu K, Saito Y, Watanabe M, Morita T, Hida J. Lymph node ratio is a powerful prognostic index in patients with stage III distal rectal cancer: a Japanese multicenter study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:891-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Song YX, Gao P, Wang ZN, Tong LL, Xu YY, Sun Z, Xing CZ, Xu HM. Which is the most suitable classification for colorectal cancer, log odds, the number or the ratio of positive lymph nodes? PLoS One. 2011;6:e28937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Wang J, Hassett JM, Dayton MT, Kulaylat MN. The prognostic superiority of log odds of positive lymph nodes in stage III colon cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1790-1796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |