Published online Apr 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i15.2425

Revised: January 25, 2013

Accepted: February 5, 2013

Published online: April 21, 2013

Processing time: 164 Days and 11.1 Hours

AIM: To compare the effectiveness and safety of endoscopic papillary balloon intermittent dilatation (EPBID) and endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) in the treatment of common bile duct stones.

METHODS: From March 2011 to May 2012, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed in 560 patients, 262 with common bile duct stones. A total of 206 patients with common bile duct stones were enrolled in the study and randomized to receive either EPBID with a 10-12 mm dilated balloon or EST (103 patients in each group). For both groups a conventional reticular basket or balloon was used to remove the stones. After the procedure, routine endoscopic nasobiliary drainage was performed.

RESULTS: First-time stone removal was successfully performed in 94 patients in the EPBID group (91.3%) and 75 patients in the EST group (72.8%). There was no statistically significant difference in terms of operation time between the two groups. The overall incidence of early complications in the EPBID and EST groups was 2.9% and 13.6%, respectively, with no deaths reported during the course of the study and follow-up. Multiple regression analysis showed that the success rate of stone removal was associated with stone removal method [odds ratio (OR): 5.35; 95%CI: 2.24-12.77; P = 0.00], the transverse diameter of the stone (OR: 2.63; 95%CI: 1.19-5.80; P = 0.02) and the presence or absence of diverticulum (OR: 2.35; 95%CI: 1.03-5.37; P = 0.04). Postoperative pancreatitis was associated with the EST method of stone removal (OR: 5.00; 95%CI: 1.23-20.28; P = 0.02) and whether or not pancreatography was performed (OR: 0.10; 95%CI: 0.03-0.35; P = 0.00).

CONCLUSION: The EPBID group had a higher success rate of stone removal with a lower incidence of pancreatitis compared with the EST group.

Core tip: Previous studies have shown that endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation with a 8 mm dilated balloon and endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) have similar success rates in terms of stone removal. The incidence of postoperative pancreatitis with these procedures is high, so its application is limited. We compared the safety and efficacy of endoscopic papillary balloon intermittent dilatation, with an increase in dilated balloon diameter (10-12 mm) and extended dilatation time, and EST in the treatment of common bile duct stones (transverse diameter ≤ 12 mm).

- Citation: Fu BQ, Xu YP, Tao LS, Yao J, Zhou CS. Endoscopic papillary balloon intermittent dilatation and endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(15): 2425-2432

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i15/2425.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i15.2425

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has gradually replaced a surgical operation and become the preferred method for the treatment of common bile duct stones because of its minimal invasiveness and low cost. There are two main ERCP methods for treating choledocholithiasis: endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation (EPBD) and endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST). Previous studies have shown that EPBD with an 8 mm dilated balloon and EST have similar success rates in terms of stone removal. The incidence of postoperative pancreatitis with these procedures is high[1], so their application is limited. In recent years, some studies showed that the incidence of postoperative pancreatitis was reduced when the dilatation diameter was larger and the dilatation time was extended during EPBD[2,3]. However, few studies have compared EST and EPBD which had an increased dilatation diameter and extended dilatation time. We compared the safety and efficacy of endoscopic papillary balloon intermittent dilatation (EPBID) and EST in the treatment of common bile duct stones (transverse diameter ≤ 12 mm) after increasing the dilated balloon diameter (10-12 mm) and extending the dilatation time. This study was conducted at the People’s Hospital affiliated to Jiangsu University. The study was approved by the hospital’s ethics committee.

From March 2011 to May 2012, ERCP was performed at our hospital on common bile duct stones and a medical X-ray gauge (Philips EasyDiagnost 4.0) was used to measure the transverse diameter of stones. During this period, 206 consecutive patients (97 male, 109 female) with a stone transverse diameter of ≤ 12 mm were identified. Patient age ranged from 15 to 93 years (median: 61 years). Patients who had previously undergone EPBD or EST for stone removal, distal common bile duct stenosis, stones with transverse diameters greater than 12 mm, severe coagulation dysfunction, hepatobiliary and/or pancreatic duct malignant tumor, or calculus incarceration in the duodenal papilla were excluded from the study.

According to the requirement of randomized controlled trials, the treatment schemes were randomly generated and put into sealed capsules. After the bile duct cannula was successfully performed, the researchers randomly chose a capsule to allocate patients into the EPBID or EST group. Neither the patients nor the endoscopy doctors were aware of the treatment option the patient would receive. There were specialized researchers observing and recording the experimental procedures to ensure that the experiment was conducted according to the appropriate procedures.

Equipment included an Olympus JF-240/TJF-240 electronic duodenoscope, standard radiographic catheters, smart-type pulling papillotome, Boston 30 mm × 10 mm dilating balloon (balloon length 30 mm, maximum dilated diameter 12 mm), ERBE200 high-frequency electrosurgical generator, mechanical lithotripsy basket, reticular basket and balloon catheter.

Preoperative preparations: all patients were asked to fast for 12 h prior to the start of the procedure. Scopolamine butylbromide (10 mg), dolantin (50 mg) and valium (10 mg) were injected intramuscularly 20 min before the start of the procedure to suppress intestinal peristalsis, alleviate pain and provide sedation. Lidocaine hydrochloride mucilage was used to provide local anesthesia of the throat.

EPBID procedure: The presence of common bile duct stones (maximum diameter less than or equal to 12 mm) was confirmed by cholangiography. Based on the stone size, the balloon was dilated to 10-12 mm using a pressure pump. The pressure was maintained for about 1 min and removed after 30 s. One minute pressure followed by 30 s relaxation was repeated two more times (total dilatation time: 3 min).

EST procedure: The presence of common bile duct stones (maximum diameter less than or equal to 12 mm) was confirmed by cholangiography. Endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed at an 11/12 o’clock position. The incision length (medium-large incision) was determined according to the stone size.

Steps performed similarly within the two groups: Use of a reticular basket or balloon catheter to remove the common bile duct stones, use of mechanical lithotripsy basket to break the stones or expand the incision length or increase the dilated balloon diameter if stone removal failed. If another failure occurred, the application of an indwelling nasobiliary tube and scheduling for ERCP on a different day, or a referral for a surgical operation was given. The nasobiliary tube was inserted into all patients after the procedure, and 3 d later nasobiliary duct radiography was performed to check for residual stones.

Operation time: The time taken from the beginning of papilla incision or dilatation until the end of stone removal.

Lithotomy success or failure: Complete removal of the stones using a conventional reticular basket or balloon was deemed a success. The following scenarios were all considered as failed lithotomy: removal of the stones through mechanical lithotripsy, expanding endoscopic incision or increasing the balloon dilatation diameter, referral for surgery, or identifying residual stones in postoperative nasobiliary drainage radiography.

Postoperative clinical symptoms and laboratory parameters: Postoperative clinical symptoms and laboratory parameters including abdominal pain, tenderness, nausea, vomiting, fever and melena 4, 12 and 24 h after the procedure, and blood amylase were recorded.

Follow up: One month after operation, the patients were followed up by telephone to check for any symptoms.

ERCP postoperative pancreatitis was diagnosed using the following criteria: No pancreatitis existed before the procedure; 4 h after the procedure, the blood amylase level was increased to over 3 times higher than the upper normal limit accompanied by abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, fever or signs of peritoneal irritation and other clinical symptoms; or morphological changes of the pancreas were detected via imaging techniques.

Endoscopic bleeding observed: ERCP postoperative bleeding was defined as having hematemesis, melena and other clinical manifestations accompanied by a decrease in hemoglobin levels (at least 2 g/dL)[4-7], after the exclusion of other possible causes for upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopic bleeding observed during the procedure was not considered as ERCP postoperative bleeding.

Other complications: Patients were considered to have biliary infections if they had a body temperature above 38 °C, right upper abdominal pain, and increased total leukocyte and neutrophil differential counts. Gastrointestinal perforation was diagnosed in the presence of abdominal pain and radiographic evidence.

Stata7.0 was used for statistical analysis. Measurement data were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using the Student t test. Numerical data were compared using the χ2 test. Logistic regression analysis was applied to evaluate the success rate of the procedures and the incidence rates of complications. Regression analysis was performed to determine any correlations of success rate of the procedures, postoperative pancreatitis and postoperative bleeding with respect to sex, age (< 60 and ≥ 60 group), presence of a diverticulum near papilla, diameter of the common bile duct (< 12 mm and ≥ 12 mm), maximum transverse diameter of the stone (< 10 mm and 10-12 mm), number of stones (1 or ≥ 2), application of pre-cut, stone removal methods, and use of pancreatography (if the guide wire was inserted into the bile duct more than 4 times it was considered as pancreatography). Statistical significance for all tests was set at P < 0.05.

The differences in sex, age, common bile duct diameter, transverse diameter of the stone, and number of stones between the two groups were not statistically significant (P > 0.05, Table 1).

| Group | EPBID | EST | P value |

| Male/female | 52/51 | 45/58 | 0.33 |

| Age (yr) | 61.83 ± 17.36 | 60.48 ± 14.69 | 0.55 |

| Common bile duct diameter (mm) | 12.74 ± 2.79 | 12.55 ± 3.05 | 0.65 |

| Transverse diameter of stone (mm) | 8.38 ± 2.67 | 7.71 ± 2.35 | 0.06 |

| No. of stones | 2.17 ± 1.43 | 1.89 ± 1.37 | 0.15 |

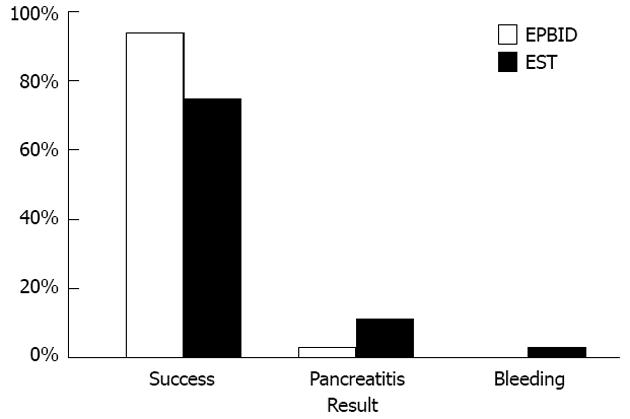

First-time stone removal was successfully carried out in 94 cases in the EPBID group (91.3%) and in 75 cases in the EST group (72.8%). The success rate of stone removal in the EPBID group was significantly higher than that of the EST group (P < 0.05, Figure 1; Table 2). For those with a transverse stone diameter of < 10 mm, the success rate of stone removal in the EPBID and EST groups was 53 out of 54 (98.1%), and 55 out of 71 (77.5%), respectively. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.05, Table 2). For the group of patients with stone transverse diameters of 10-12 mm, the stone-removal success rate of the EPBID and EST groups was 41 out of 49 (83.7%) and 20 out of 32 (62.5%), respectively, with statistical significance (P < 0.05, Table 2) favoring the EPBD group.

| Group | EPBID | EST | P value |

| Success rate of stone removal | 94/103 | 75/103 | 0.00 |

| Transverse diameter of stone < 10 mm | 53/54 | 55/71 | 0.00 |

| Transverse diameter of stone ≥ 10 mm | 41/49 | 20/32 | 0.03 |

| Operation time (min) | 9.86 ± 5.21 | 9.03 ± 4.92 | 0.29 |

The stone removal time for the EPBD and EST groups were 9.86 ± 5.21 min and 9.03 ± 4.92 min, respectively, and showed no significant difference (P > 0.05, Table 2).

In the EPBID group a total of 9 cases failed of which 3 were transferred for surgical operations; 3 were referred for mechanical lithotripsy, and 2 underwent an increase in dilated balloon diameter. Radiography found residual stones in one patient in the EPBID group who subsequently underwent ERCP a second time.

In the EST group a total of 28 cases failed, of which 2 were transferred to surgical operations, 3 underwent enlargement of the incision, 9 were transferred to receive balloon dilatation, and 4 received mechanical lithotripsy. Through radiography, residual stones in 10 patients of the EST group were found, for which the ERCP procedure was performed a second time.

In the EPBID and EST groups there were 88 cases without pancreatitis before the operation. Three patients in the EPBID group reported postoperative pancreatitis while 11 patients in the EST group reported postoperative pancreatitis. All the cases of pancreatitis were mild. The incidence of pancreatitis in the EPBID group was statistically significantly lower than in the EST group (3.4% vs 12.5%; P < 0.05; Figure 1; Table 3). For the group of patients who had stones with a transverse diameter < 10 mm, the incidence of pancreatitis in the EPBID and EST groups was 0% (0 out of 43) and 11.5% (7 out of 61), respectively, and showed a clinically significant difference favoring the EPBID group (P < 0.05, Table 2). For the group of patients with stones of a transverse diameter of 10-12 mm, the incidence of pancreatitis in the EPBID group was 6.7% (3 out of 45) and the incidence of pancreatitis in the EST group was 14.8% (4 out of 27), with no significant difference (P > 0.05, Table 2). Also, no significant difference was seen between the 2 groups in terms of the incidence of postoperative bleeding (0% in EPBID group and 2.9% in EST group; P > 0.05, Figure 1; Table 3). Overall, no perforations and postoperative cholangitis was observed in any patient. The doctors evaluating the postoperative complications of the patients did not know which treatment methods had been used for the treatment of each particular patient.

| Group | EPBID | EST | P value |

| Pancreatitis | 3/88 | 11/88 | 0.03 |

| Transverse diameter of stone < 10 mm | 0/43 | 7/61 | 0.04 |

| Transverse diameter of stone ≥ 10 mm | 3/45 | 4/27 | 0.41 |

| Bleeding | 0/103 | 3/103 | 0.25 |

The success rate of stone removal was related to the stone removal method, the presence or absence of papilla diverticulum, and the maximum transverse diameter of the common bile duct stones (< 10 mm vs 10-12 mm group) (P < 0.05, Tables 4 and 5). Postoperative pancreatitis was related to whether pancreatography was performed, and the method used for stone removal (P < 0.05, Tables 6 and 7). This study did not identify risk factors related to postoperative bleeding.

| Factor | Sample size | Success | Sample size | Failure | OR | P value |

| Age (yr) | 169 | 60.30 ± 16.62 | 37 | 64.60 ± 12.81 | 1.31 | 0.14 |

| Sex | 1.59 | 0.21 | ||||

| Male | 83 | 49.11% | 14 | 37.84% | ||

| Female | 86 | 50.89% | 23 | 62.16% | ||

| Papilla diverticulum | 2.25 | 0.03 | ||||

| Yes | 36 | 21.30% | 14 | 37.84% | ||

| No | 133 | 78.70% | 23 | 62.16% | ||

| Papilla pre-cut | 0.91 | 0.93 | ||||

| No | 164 | 97.04% | 36 | 97.30% | ||

| Yes | 5 | 2.96% | 1 | 2.70% | ||

| Performance of pancreatography | 0.50 | 0.18 | ||||

| Yes | 15 | 8.88% | 6 | 16.22% | ||

| No | 154 | 91.12% | 31 | 83.78% | ||

| Stone removal method | 3.90 | 0.00 | ||||

| EPBD | 94 | 55.62% | 9 | 24.32% | ||

| EST | 75 | 44.38% | 28 | 75.68% | ||

| Common bile duct diameter | 169 | 12.38 ± 2.49 | 37 | 13.86 ± 4.21 | 3.26 | 0.00 |

| Common bile duct stone number | 169 | 2.02 ± 1.43 | 37 | 2.08 ± 1.32 | 1.65 | 0.82 |

| Maximum transverse diameter of stone | 169 | 7.81 ± 2.53 | 37 | 9.11 ± 2.28 | 2.08 | 0.00 |

| Factors | β | SE | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Stone removal method | 1.68 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 5.35 | 2.24-12.77 |

| Whether there is diverticulum | 0.85 | 0.42 | 0.04 | 2.35 | 1.03-5.37 |

| Stone transverse diameter | 0.97 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 2.63 | 1.19-5.80 |

| Constant term | -3.22 | 0.48 | 0.00 |

| Factor | Sample size | No pancreatitis | Sample size | Pancreatitis | OR | P value |

| Age | 162 | 60.33 ± 16.17 | 14 | 64.29 ± 14.58 | 1.09 | 0.38 |

| Sex | 1.51 | 0.47 | ||||

| Male | 74 | 45.68% | 5 | 35.71% | ||

| Female | 88 | 54.32% | 9 | 64.29% | ||

| Papilla diverticulum | 1.75 | 0.34 | ||||

| Yes | 39 | 24.07% | 5 | 35.71% | ||

| No | 123 | 75.93% | 9 | 64.29% | ||

| Papilla pre-cut | 8.83 | 0.05 | ||||

| No | 159 | 98.15% | 12 | 85.71% | ||

| Yes | 3 | 1.85% | 2 | 14.29% | ||

| Performance of pancreatography | 0.12 | 0.00 | ||||

| Yes | 13 | 8.02% | 6 | 42.86% | ||

| No | 149 | 91.98% | 8 | 57.14% | ||

| Stone removal method | 4.05 | 0.03 | ||||

| EPBD | 85 | 52.47% | 3 | 21.43% | ||

| EST | 77 | 47.53% | 11 | 78.57% | ||

| Common bile duct diameter | 162 | 12.64 ± 2.98 | 14 | 13.86 ± 2.98 | 2.53 | 0.15 |

| Common bile duct stone number | 162 | 2.09 ± 1.46 | 14 | 1.43 ± 0.85 | 0.46 | 0.10 |

| Transverse diameter of stone | 162 | 8.17 ± 2.45 | 14 | 8.29 ± 2.64 | 1.49 | 0.86 |

| Factor | β | SE | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Performance of pancreatography | -2.35 | 0.66 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.03-0.35 |

| Stone removal method | 1.61 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 5.00 | 1.23-20.28 |

| Constant term | -1.66 | 0.69 | 0.02 |

The ERCP procedure has become the main method for the treatment of common bile duct stones because it is less invasive and has a lower cost than EST. Kawai et al[8] first reported on EST; since then, EST has been widely accepted as an option in the clinical management of the disease and has gradually replaced surgical operations. However, since EST causes damage to the papilla sphincter, it is generally believed to have a negative lasting impact on papilla sphincter function. In 1983, Staritz et al[9] introduced EPBD for the first time. Since EPBD does not require sphincterotomy, it is believed that EPBD can better protect sphincter function compared with EST, whereas EST results in a permanent loss of sphincter function[10,11]. However, Takezawa et al[12] suggested that the difference between the two methods in protecting papilla sphincter function is not statistically significant. Both domestic and international research studies showed that, compared with EPBD, EST had a higher stone recurrence rate[13-15]. Most recently, a method that uses larger dilated balloons (EPLBD) that requires a small incision has been performed for larger stones[16-21]. Kim et al[18] showed that for the stones with a transverse diameter greater than 10 mm, the first-time success rate of stone removal by EPLBD is higher than that of simple sphincterotomy. In addition, EPBLD can reduce the probability of mechanical lithotripsy with no additional incidence of complications.

Yu et al[22] indicated that the difference in the success rate for stone removal between EST and EPBD was not statistically significant. Their overall success rate of stone removal for EST and EPBD was 97.5% and 98.1% respectively (first-time success rate of 70% and 65%, respectively). In our study however, the success rate of stone removal of the EPBID group (91.3%) was significantly higher than that of the EST group (72.8%). Conventional EPBD usually uses smaller dilated balloon diameters (around 8 mm) and a short dilatation time. However, in this investigation, the dilatation diameter was larger, and the dilatation time was extended making the pathway of stone removal wider and leading to a higher success rate of stone removal. Multiple regression analysis showed that the success rate of stone removal was related to the method of stone removal, the transverse diameter of the stones and the presence or absence of diverticulum. Often, when the transverse diameter of a stone is larger it is more difficult to remove. In these cases, mechanical lithotripsy, enlargement of the incision or increasing the dilated balloon diameter may be required. In this investigation, no significant difference between the two groups was seen in terms of stone removal time.

Liu et al[1] indicated that EPBD had a much lower incidence of postoperative bleeding than EST, but its incidence of postoperative pancreatitis was significantly higher than that of EST. The mechanism of the development of EPBD-induced postoperative pancreatitis is thought to be due to compartment syndrome. Two hours after EPBD procedures, the papilla develops inflammatory edema. The papillary sphincter does not relax sufficiently, which restricts the expansion of the internal contents and results in compartment syndrome. This finally leads to poor drainage of pancreatic fluid and postoperative pancreatitis[2,23]. We believe that if the balloon diameter is small in EPBD, bile will not be easily discharged and would flow back to the pancreatic duct, thus increasing the risk of pancreatitis; in addition, the smaller the dilatation diameter, the slower the removal of the stone. The reticular basket or balloon is required to be repeatedly moved forward and backward through the papilla passage, which could induce further tissue edema. In our investigation, by increasing the dilated balloon diameter, and the time of intermittent dilatation (the total time of dilatation was three minutes), the papilla sphincter was torn apart and fully relaxed, alleviating papillary edema and reducing the obstruction of the pancreatic duct. Therefore, postoperative bile excretion was easier and reduced the risk of postoperative pancreatitis.

The results of this study also suggest that the risk of postoperative pancreatitis is related to whether pancreatography was performed as well as the method of stone removal. In the course of pancreatography, contrast medium bubbles enter the pancreatic duct, and the internal pressure of the pancreatic duct increases making the pancreas prone to inflammation. If the guidewire repeatedly comes into the pancreatic duct it is highly likely to cause edema around the pancreatic duct orifice and would then contribute to postoperative pancreatitis. Ueki et al[24] showed that postoperative pancreatitis was related to pre-cut sphincterotomy (PST) because cannulation was often difficult in patients who received PST, and their operation time was longer, causing papillary edema. In this investigation, there were a few cases of PST and the difference in the incidence of pancreatitis between the groups had no statistical significance. The results of this study showed that in the EPBD group, 3 cases of postoperative pancreatitis occurred in those patients who had stones of < 10 mm in diameter. The development of pancreatitis was more common in the patients of the EST group who had stones of over 10 mm in diameter. However, because the sample size was small, statistical significance could not be shown. Previous studies suggest that the possibility of EST postoperative bleeding was between 2.5% and 5%[6]. In this investigation the EST group had 3 patients who suffered from complicated postoperative bleeding while no patient in the EPBD group experienced complicated postoperative bleeding; however, due to the small sample size there was no statistical significance. There were no cases of duodenal perforations, cardiovascular accidents or other complications.

This study was different because of the increase in the dilated balloon diameter in EPBD and of the extended time of intermittent dilatation. The first 1-min balloon dilatation tore apart the papilla sphincter; the second and the third 1-min balloon dilatations compressed the bleeding caused by the first dilatation tear and further tore the papilla sphincter, while avoiding long-time compression of the pancreatic duct orifice. This was intended to remove the stone and reduce the incidence of postoperative pancreatitis. Results of this study indicate that by increasing the balloon dilatation diameter and extending the dilatation time in EPBD, bile duct stones with transverse diameters smaller than 12 mm could be removed in a quicker, more effective way compared with EST. The use of EPBD can also reduce significantly the incidence of postoperative pancreatitis. Bang et al[25] showed that continuous endoscopic dilatations for 20 s and 60 s were not significantly different in the success rate of stone removal and in the incidence of postoperative pancreatitis. We believe that extending the papillary dilatation time to 60 s is still insufficient to fully clear the passage. Liao et al[3] showed that continuous endoscopic dilatation for 5 min, rather than 1 min, resulted in a higher success rate of stone removal, and significantly decreased the incidence of postoperative pancreatitis. The results of this study showed that the EPBD group had a success rate of up to 98.1% for the removal of stones of a maximum transverse diameter of 10 mm. Therefore, properly increasing the dilatation diameter and extending the dilatation time can contribute to a higher success rate in stone removal and lower the risk of postoperative pancreatitis. However, it should be noted that an excessive increase in the diameter of balloon dilatation could increase the chance of perforation. Theoretically speaking, the balloon dilatation diameter determines the size of the stones removed, and the method of using a 10 mm-diameter balloon for continuous dilatation for 5 min adopted by Liao et al[3] applies to stones with a size of 15 mm. Therefore, further research is needed to provide more details on the optimal dilatation time and diameter as well as their relationship to the transverse diameter of the stone.

Choledocholithiasis is a common disease in the gastroenterology clinic, and can cause biliary obstruction, acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis, acute pancreatitis, hepatic failure, gallstone shock, even threaten patient’s life. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has gradually replaced surgery and become the preferred method for the treatment of common bile duct stones because of its minimal invasiveness and low cost. There are two main ERCP methods for treating choledocholithiasis: endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation (EPBD) and endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST). Since EPBD does not require sphincterotomy, it is believed that EPBD can protect sphincter function better than EST.

Previous studies have shown that EPBD with a 8 mm dilated balloon and EST have similar success rates in terms of stone removal. The incidence of postoperative pancreatitis with these procedures is high, so its application is limited. In recent years, some studies showed that the incidence of postoperative pancreatitis could be reduced when the dilatation diameter was larger and the dilatation time was extended during EPBD. Recent studies indicated that a small incision plus endoscopic papillary balloon intermittent dilatation (EPBID) had more advantages over EST in treating larger diameter (> 15 mm) common bile duct stones.

There are few studies focusing on the comparison of EST and EPBID with increased dilatation diameter and extended dilatation time. We compared the safety and efficacy of EPBID and EST in the treatment of common bile duct stones (transverse diameter ≤ 12 mm) after increasing the dilated balloon diameter (10-12 mm) and extending the dilatation time. The advantages of EPBID are larger dilatation diameter, longer dilatation time, less bleeding.

EPBD have several advantages over EST, such as no incision, lower operational difficulty, less bleeding and less perforation, therefore EPBD would be suitable for novices to remove the common bile duct stones.

EPBID: Duodenal side mirrors was inserted into the duodenal papilla, then the guide wire was inserted into bile duct, and balloon catheter was put in common bile duct, the balloon was dilated 10 to 12 mm using a pressure pump. The pressure was maintained for about 1 min and removed for 30 s. One-minute pressure followed by the 30 s relaxation was repeated two more times (total dilatation time: 3 min). Then the common bile duct stones were removed by using the reticular basket or the balloon catheter.

This is an interesting manuscript comparing EPBID and EST for normal size stones. It has an important impact on the further expansion of EPBID as a technology for remove of bile duct stones.

P- Reviewers Yamamoto S, Marks JM S- Editor Song XX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Liu Y, Su P, Lin S, Xiao K, Chen P, An S, Zhi F, Bai Y. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation versus endoscopic sphincterotomy in the treatment for choledocholithiasis: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:464-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Baron TH, Harewood GC. Endoscopic balloon dilation of the biliary sphincter compared to endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy for removal of common bile duct stones during ERCP: a metaanalysis of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1455-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liao WC, Lee CT, Chang CY, Leung JW, Chen JH, Tsai MC, Lin JT, Wu MS, Wang HP. Randomized trial of 1-minute versus 5-minute endoscopic balloon dilation for extraction of bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1154-1162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. The benefits of endoscopic nasobiliary drainage without sphincterotomy for acute cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2065-2068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1689] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2036] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Mallery JS, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, Goldstein JL, Hirota WK, Jacobson BC, Leighton JA, Raddawi HM, Varg JJ, Waring JP. Complications of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:633-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kawai K, Akasaka Y, Murakami K, Tada M, Koli Y. Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc. 1974;20:148-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Staritz M, Ewe K, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH. Endoscopic papillary dilatation, a possible alternative to endoscopic papillotomy. Lancet. 1982;1:1306-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Minami A, Nakatsu T, Uchida N, Hirabayashi S, Fukuma H, Morshed SA, Nishioka M. Papillary dilation vs sphincterotomy in endoscopic removal of bile duct stones. A randomized trial with manometric function. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:2550-2554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bergman JJ, van Berkel AM, Groen AK, Schoeman MN, Offerhaus J, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Biliary manometry, bacterial characteristics, bile composition, and histologic changes fifteen to seventeen years after endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:400-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Takezawa M, Kida Y, Kida M, Saigenji K. Influence of endoscopic papillary balloon dilation and endoscopic sphincterotomy on sphincter of oddi function: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2004;36:631-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fujita N, Maguchi H, Komatsu Y, Yasuda I, Hasebe O, Igarashi Y, Murakami A, Mukai H, Fujii T, Yamao K. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation for bile duct stones: A prospective randomized controlled multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:151-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Komatsu Y, Kawabe T, Toda N, Ohashi M, Isayama M, Tateishi K, Sato S, Koike Y, Yamagata M, Tada M. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for the management of common bile duct stones: experience of 226 cases. Endoscopy. 1998;30:12-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sugiyama M, Suzuki Y, Abe N, Masaki T, Mori T, Atomi Y. Endoscopic retreatment of recurrent choledocholithiasis after sphincterotomy. Gut. 2004;53:1856-1859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Feng Y, Zhu H, Chen X, Xu S, Cheng W, Ni J, Shi R. Comparison of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation and endoscopic sphincterotomy for retrieval of choledocholithiasis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:655-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim HG, Cheon YK, Cho YD, Moon JH, Park do H, Lee TH, Choi HJ, Park SH, Lee JS, Lee MS. Small sphincterotomy combined with endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation versus sphincterotomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4298-4304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kim TH, Oh HJ, Lee JY, Sohn YW. Can a small endoscopic sphincterotomy plus a large-balloon dilation reduce the use of mechanical lithotripsy in patients with large bile duct stones? Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3330-3337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Stefanidis G, Viazis N, Pleskow D, Manolakopoulos S, Theocharis L, Christodoulou C, Kotsikoros N, Giannousis J, Sgouros S, Rodias M. Large balloon dilation vs. mechanical lithotripsy for the management of large bile duct stones: a prospective randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:278-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lin CK, Lai KH, Chan HH, Tsai WL, Wang EM, Wei MC, Fu MT, Lo CC, Hsu PI, Lo GH. Endoscopic balloon dilatation is a safe method in the management of common bile duct stones. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bang S, Kim MH, Park JY, Park SW, Song SY, Chung JB. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation with large balloon after limited sphincterotomy for retrieval of choledocholithiasis. Yonsei Med J. 2006;47:805-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yu T, Liu L, Chen J, Li YQ. A comparison of endoscopic papillary balloon dilation and endoscopic sphincterotomy for the removal of common bile duct stones. Zhonghua Neike Zazhi. 2011;50:116-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mac Mathuna P, Siegenberg D, Gibbons D, Gorin D, O’Brien M, Afdhal NA, Chuttani R. The acute and long-term effect of balloon sphincteroplasty on papillary structure in pigs. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:650-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ueki T, Otani K, Fujimura N, Shimizu A, Otsuka Y, Kawamoto K, Matsui T. Comparison between emergency and elective endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with acute cholangitis due to choledocholithiasis: is emergency endoscopic sphincterotomy safe? J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1080-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bang BW, Jeong S, Lee DH, Lee JI, Lee JW, Kwon KS, Kim HG, Shin YW, Kim YS. The ballooning time in endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for the treatment of bile duct stones. Korean J Intern Med. 2010;25:239-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |